Old Tin Van

Ôi anh em Cộng Hoà

Các anh Cộng Hoà đã chiến đấu cho Tây Ban Nha

xứ sở Lope de Vega Garcia Lorca

một Breton tình điên còn nức nở

mà Hi vọng Malraux còn thổn thức

và mãi Ernest còn tiếc thương

Andalousie đói quên khiêu vũ

Việt Nam ốm yếu quên ca dao

chẳng bao giờ

chẳng bao giờ

các anh quên kỉ niệm buồn của thế kỉ

chắc các anh chưa đọc bài thơ nào

đời nhược tiểu

chúng tôi đến sau hai mươi năm

cuộc chiến kéo dài qua chúng tôi ở đây

thêm sự phản trắc nặng nề

cộng sản

TTT: Tôi không còn

cô độc

Books, arts and culture

Poetry and politics

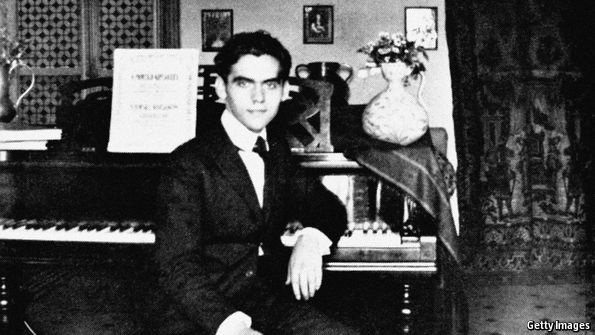

The resurrection of Federico García Lorca

JUST OVER 80 years ago, Francisco Franco triggered a military uprising against his country’s government. Granada, one of Spain’s most historic cities, fell quickly to Franco’s rebel Nationalists. Exactly a month after the outbreak of civil war, an infamous murder— which might never have happened had Franco not rebelled—took place on that city’s outskirts.

At 38, Federico García Lorca was one of Spain’s best-known writers. He had made his mark in the 1920s with lyric poetry that drew on the folk customs and haunting landscapes of his native Andalusia. This is most true of “Romancero Gitano” (1928, meaning “Gypsy Ballads”), a collection of poems of gypsy feuds and conflicts with the police, and suffused with images of the moon, blood and the colour green. The book is perhaps his greatest single volume, and it made his name.

His breakthrough as a playwright arrived in 1933 with his first full-length drama “Bodas de Sangre” (“Blood Wedding”), a fierce tragedy in which a man and his former lover, about to be someone else’s bride, run off together into a forest. In interviews, meanwhile, García Lorca had begun to give clear vent to his anti-fascism. He also made enemies among his home-town’s middle class, whom he insulted in one national newspaper as “the worst…in Spain today”. Many of this middle class had sided with the rebels and were keen to flush out any “reds” that sympathised, or seemed to sympathise, with the Republic.

García Lorca, who had returned from Madrid in July 1936 to his Granada parental home for the summer, was inevitably counted among their ranks. His homosexuality only served to intensify this hatred. Most likely on the orders of Granada’s Falangist governor, the writer was arrested on August 16th 1936 and executed three days later. One of García Lorca’s assassins boasted that he had fired “two bullets into his arse for being queer”. The location of the crime is well-known, but his body has never been found.

For years after Franco’s victory in 1939, open discussion in Spain about García Lorca’s life, sexuality and death did not take place. Until the dictator’s death in 1975, only redacted versions of his works were available and Ian Gibson's account of the poet’s murder was prohibited. Sonnets addressed to a lover (identified four years ago as Juan Ramírez de Lucas) did not appear until 1983. By then, however, in Spain as elsewhere, critical appreciation of García Lorca’s reputation as a writer of high originality had begun to supersede concerns over his sexuality.

Today, interest in García Lorca’s life and works is revived. Last month at Sadler’s Wells in London he was movingly evoked in “Patrias” (meaning homelands), a flamenco show created by Paco Peña. García Lorca was impassioned by flamenco, specifically the gypsy idiom known as “deep song”—“a stammer”, he wrote, “…a marvellous buccal undulation that smashes…our tempered scale”. “Patrias” tells his story through flamenco dance and searing songs; images of the war and of the poet are screened onto the back of the stage as the sombre performance unfolds.

As Mr Peña, who was born in Cordoba, explained to Prospero: “Thoughts about the civil war and where García Lorca came from—the land to which he was profoundly attached—led me to connect the tragedy of his death with the conflict that was the huge topic of my early life. It seemed important to me as a flamenco musician to express this suffering.”

Indeed, acute suffering is at the heart of “Yerma”, which García Lorca penned over several years from 1930. Yerma is desperate to conceive but her husband Juan will not—or cannot—impregnate her. The play’s Madrid première in 1934 was a huge success, but its frank exploration of the intimacies and agonies of rural marriage stimulated the wrath of the Catholic right.

A new version of “Yerma” opens at the Young Vic Theatre on August 4th, a fortnight short of the 80th anniversary of García Lorca’s death. Its director Simon Stone has adapted it significantly, bringing the taboo issue of childlessness to contemporary London. “I’m asking whether what shocked people over 80 years ago is still shocking now,” he says. “Is it OK to discuss this? How many women today are walking around with this crisis relationship with their bodies?”

Mr Stone is interested in taking García Lorca out of Spain, just as Euripides’s “Medea” and Sophocles’s “Antigone” can be, and often are, taken out of the ancient world. He believes that “Yerma” has a comparably dense mythic, and therefore universal, quality. “It’s a bit like the supposed Russian-ness of Chekhov or the Norwegian-ness of Ibsen. These things should not be fixed. My ‘Yerma’ is for now.”

Federico García Lorca was a man of rare gifts and, for his exuberance and inventiveness, much loved by those who knew him. All that came to a shocking end 80 years ago. It is a small mercy that in his short life he found the forms to speak to audiences across time.

Eastern European

writing

Svetlana Alexievich’s monument to those left behind

Aug 1st 2016, 12:18 by A.B.C.

NON-FICTION, in

the right hands, can prove to be more powerful and perplexing

than novels. This is the case with Svetlana Alexievich, an author

and investigative journalist who won last year’s Nobel prize in

literature for her “polyphonic writings”. “Second-hand time”, her

latest book to be translated into English, is her most ambitious

yet. From the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ms Alexievich

spent two decades writing down the stories of ordinary people in her

native Belarus and beyond. Her book is a unique chronicle of that

time and place, yet its themes of hope and loss are universal.

NON-FICTION, in

the right hands, can prove to be more powerful and perplexing

than novels. This is the case with Svetlana Alexievich, an author

and investigative journalist who won last year’s Nobel prize in

literature for her “polyphonic writings”. “Second-hand time”, her

latest book to be translated into English, is her most ambitious

yet. From the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ms Alexievich

spent two decades writing down the stories of ordinary people in her

native Belarus and beyond. Her book is a unique chronicle of that

time and place, yet its themes of hope and loss are universal.

The stories pile up over 700 pages, with love, death and everyday concerns jostling for attention. In the cramped kitchens Ms Alexievich visits, the mundane and historic overlap. The voices she records—named and unnamed, literary Muscovites, Belarusian villagers, Party officials and mothers—repeat themselves, and each other. They argue about whether Stalin and Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, were villains or heroes. As their world crumbles, people seek solace in books, God, alcohol or suicide. Salami becomes one of the symbols of this brave new world; one man calls it the “benchmark of our existence”, suddenly abundant, though not necessarily affordable.

As in the author’s earlier books, war forms an omnipresent backdrop to their narratives. Older people recall the horror and glory of the second world war, the subject of her “War’s Unwomanly Face”. The present is warlike too; street vendors by the metro make one woman think of a “war film”. Reds clash with Whites, like after the October Revolution of 1917, and history seems to be repeating itself. “Were things any different in 1917? Some people were shooting while others were dancing at balls,” one woman wonders. This cyclical element gives the book its title, with one person observing that “the future is, once again, not where it ought to be. Our time comes to us second hand.”

Amid the new uncertainty, people cling to books and words. Lovers reading an underground copy of the memoirs of poet Osip Mandelstam’s widow forget to kiss, “that’s how ardently we believed that the word could change the world”. The language of the book is lyrical but simple, using words that are short, concrete and vivid. Bela Shayevich’s translation from the original Russian runs smoothly, despite the abundance of terms and cultural references that may be unfamiliar to international readers. Some passages read like music.

A professional listener, Ms Alexievich manages the feat of being present and invisible at the same time. If voices are her medium, so too is silence; when a teenager hangs himself in the bathroom, or when no-one says the final words at a funeral because “they didn’t know how”. Silences have been inserted in square brackets, like stage directions or punctuation. In one of her brief asides, Ms Alexievich announces that “I want to be a cold-blooded historian, not one who is holding a blazing torch.” Yet the result is always warm and human, however dark the content. Many of the people the author meets simply want to talk, sharing memories they had held on to for years or decades. With “Second-hand time”, Ms Alexievich has built a monument to these survivors of the collapse of the Soviet Union; a monument in words.

Tờ Người Kinh Tế đọc "Thời gian xài rồi xài lại", cuốn sách mới nhất của Bà Nobel văn chương, Svetlana Alexievich.

Đây là thứ viết, theo GCC, Dương Nghiễm Mậu, vào những giây phút cuối cùng của cuộc chiến, bỏ ngòi viết nhà văn, cầm cây viết không-giả tưởng, viết "Địa Ngục Có Thật":

“I want to be a cold-blooded historian, not one who is holding a blazing torch.” Yet the result is always warm and human, however dark the content. Many of the people the author meets simply want to talk, sharing memories they had held on to for years or decades. With “Second-hand time”, Ms Alexievich has built a monument to these survivors of the collapse of the Soviet Union; a monument in words.

Vẫn theo GCC, cách viết này hợp với DNM

WRITERS LOST IN THE DISTANCE

Những nhà văn mất vào quãng xa

Svetlana Alexievich’s monument to those left behind

Aug 1st 2016, 12:18 by A.B.C.

The stories pile up over 700 pages, with love, death and everyday concerns jostling for attention. In the cramped kitchens Ms Alexievich visits, the mundane and historic overlap. The voices she records—named and unnamed, literary Muscovites, Belarusian villagers, Party officials and mothers—repeat themselves, and each other. They argue about whether Stalin and Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, were villains or heroes. As their world crumbles, people seek solace in books, God, alcohol or suicide. Salami becomes one of the symbols of this brave new world; one man calls it the “benchmark of our existence”, suddenly abundant, though not necessarily affordable.

As in the author’s earlier books, war forms an omnipresent backdrop to their narratives. Older people recall the horror and glory of the second world war, the subject of her “War’s Unwomanly Face”. The present is warlike too; street vendors by the metro make one woman think of a “war film”. Reds clash with Whites, like after the October Revolution of 1917, and history seems to be repeating itself. “Were things any different in 1917? Some people were shooting while others were dancing at balls,” one woman wonders. This cyclical element gives the book its title, with one person observing that “the future is, once again, not where it ought to be. Our time comes to us second hand.”

Amid the new uncertainty, people cling to books and words. Lovers reading an underground copy of the memoirs of poet Osip Mandelstam’s widow forget to kiss, “that’s how ardently we believed that the word could change the world”. The language of the book is lyrical but simple, using words that are short, concrete and vivid. Bela Shayevich’s translation from the original Russian runs smoothly, despite the abundance of terms and cultural references that may be unfamiliar to international readers. Some passages read like music.

A professional listener, Ms Alexievich manages the feat of being present and invisible at the same time. If voices are her medium, so too is silence; when a teenager hangs himself in the bathroom, or when no-one says the final words at a funeral because “they didn’t know how”. Silences have been inserted in square brackets, like stage directions or punctuation. In one of her brief asides, Ms Alexievich announces that “I want to be a cold-blooded historian, not one who is holding a blazing torch.” Yet the result is always warm and human, however dark the content. Many of the people the author meets simply want to talk, sharing memories they had held on to for years or decades. With “Second-hand time”, Ms Alexievich has built a monument to these survivors of the collapse of the Soviet Union; a monument in words.

Tờ Người Kinh Tế đọc "Thời gian xài rồi xài lại", cuốn sách mới nhất của Bà Nobel văn chương, Svetlana Alexievich.

Đây là thứ viết, theo GCC, Dương Nghiễm Mậu, vào những giây phút cuối cùng của cuộc chiến, bỏ ngòi viết nhà văn, cầm cây viết không-giả tưởng, viết "Địa Ngục Có Thật":

“I want to be a cold-blooded historian, not one who is holding a blazing torch.” Yet the result is always warm and human, however dark the content. Many of the people the author meets simply want to talk, sharing memories they had held on to for years or decades. With “Second-hand time”, Ms Alexievich has built a monument to these survivors of the collapse of the Soviet Union; a monument in words.

Vẫn theo GCC, cách viết này hợp với DNM

WRITERS LOST IN THE DISTANCE

Những nhà văn mất vào quãng xa

A few days ago, Juan Villoro

and I were remembering the writers who were important to us in

our youth and who today have fallen into a kind of oblivion, the

writers who at the peak of their fame had many readers and who today

suffer the ingratitude of those same readers and who-to make matters

worse-haven't managed to spark the interest of a new generation of

readers.

We thought, of course, of Henry Miller, who in his day was read all over Spain, and whose name was on everyone's lips, but whose fame was perhaps due to a misunderstanding: probably more than half the people who bought his books did so expecting to find a pornographer, which in some sense was justified, and also understandable in the Spain that emerged after almost forty years of censure under Franco and the church.

At the other extreme we remembered Artaud, the very spirit of asceticism, who in his day also sold well and had not a few Spanish and Mexican admirers, and if today one makes the mistake of mentioning his name to someone under the age of thirty, the response will surely be devastating. These days, even film buffs have never heard of Antonin Artaud.

The same is true of Macedonio Fernandez: his books-except in Argentina, I imagine-are impossible to find in book- stores. And it's true of Felisberto Hernandez, who had a small resurgence in the 1970s, but whose stories today can only be found after much searching in second-hand bookstores. Felisberto's fate, I presume, is different in Uruguay and Argentina, which brings us to a problem even worse than being forgotten: the provincialism of the book market, which corrals and locks away Spanish-language literature, which, simply put, means that Chilean authors are only of interest in Chile, Mexican authors in Mexico, and Colombians in Colombia, as if each Latin American country spoke a different language or as if t aesthetic taste of each Latin American reader were determined first and foremost by national-that is, provincial-imperatives, which wasn't the case in the 1960s, for example, when the Boom exploded, or in the 1950S or 1940s, despite poo distribution.

But anyway, that's not what Villoro and I talked about. We talked about other writers, like Henry Miller or Artaud or B. Traven or Tristan Tzara, writers who contributed to our sentimental education and who are now impossible to find in the depths of bookstores for the simple reason that they have hardly any new readers. And also about the youngest ones, writers of our generation, like Sophie Podolski or Mathieu Messagier, who were simply incredible and highly talented and who not only can no longer be found in bookstores but can't even be found on the Internet, which is saying a lot, as if they'd never existed or as if we'd imagined them. The explanation for this ebb of writers, however, is very simple. Just as love moves according to a mechanism like the sea's, as the Nicaraguan poet Martinez Rivas puts it, so too do writers move, and one day they appear and then they disappear and then maybe they appear again. And if they don't, it doesn't really matter so much, because in some secret way, they're us now.

We thought, of course, of Henry Miller, who in his day was read all over Spain, and whose name was on everyone's lips, but whose fame was perhaps due to a misunderstanding: probably more than half the people who bought his books did so expecting to find a pornographer, which in some sense was justified, and also understandable in the Spain that emerged after almost forty years of censure under Franco and the church.

At the other extreme we remembered Artaud, the very spirit of asceticism, who in his day also sold well and had not a few Spanish and Mexican admirers, and if today one makes the mistake of mentioning his name to someone under the age of thirty, the response will surely be devastating. These days, even film buffs have never heard of Antonin Artaud.

The same is true of Macedonio Fernandez: his books-except in Argentina, I imagine-are impossible to find in book- stores. And it's true of Felisberto Hernandez, who had a small resurgence in the 1970s, but whose stories today can only be found after much searching in second-hand bookstores. Felisberto's fate, I presume, is different in Uruguay and Argentina, which brings us to a problem even worse than being forgotten: the provincialism of the book market, which corrals and locks away Spanish-language literature, which, simply put, means that Chilean authors are only of interest in Chile, Mexican authors in Mexico, and Colombians in Colombia, as if each Latin American country spoke a different language or as if t aesthetic taste of each Latin American reader were determined first and foremost by national-that is, provincial-imperatives, which wasn't the case in the 1960s, for example, when the Boom exploded, or in the 1950S or 1940s, despite poo distribution.

But anyway, that's not what Villoro and I talked about. We talked about other writers, like Henry Miller or Artaud or B. Traven or Tristan Tzara, writers who contributed to our sentimental education and who are now impossible to find in the depths of bookstores for the simple reason that they have hardly any new readers. And also about the youngest ones, writers of our generation, like Sophie Podolski or Mathieu Messagier, who were simply incredible and highly talented and who not only can no longer be found in bookstores but can't even be found on the Internet, which is saying a lot, as if they'd never existed or as if we'd imagined them. The explanation for this ebb of writers, however, is very simple. Just as love moves according to a mechanism like the sea's, as the Nicaraguan poet Martinez Rivas puts it, so too do writers move, and one day they appear and then they disappear and then maybe they appear again. And if they don't, it doesn't really matter so much, because in some secret way, they're us now.

Roberto Bolano: Between Parentheses

Đọc bài viết của nhà

phê bình Nguyễn Lệ Uyên về Dương Nghiễm Mậu, (1) GCC bèn nhớ ra bài viết

này.

DNM, nếu nói về khí

phách, về nhân cách, về cá nhân

anh, thì thật là tuyệt vời, và đúng

là “tự do hay là chết”.

Nhưng… văn

chuơng, nó không phải như vậy, chán thế!

Văn của DNM có 1 thời gây chấn động Sài Gòn, nhưng thời đó qua rồi.

Đúng ra, anh phải biết điều này, và không để cho VC in lại sách của anh.

Văn của DNM có 1 thời gây chấn động Sài Gòn, nhưng thời đó qua rồi.

Đúng ra, anh phải biết điều này, và không để cho VC in lại sách của anh.

GCC đã từng nhận xét

về anh và Nguyễn Đình Toàn, như là

hai “bản sao” của một TTT, và 1 bạn văn, nhận xét, quá

đúng.

Nay post lại ở đây, và sau đó, sẽ lèm bèm về Miller, “Thầy của Thầy”, tức triết gia PCT.

Nay post lại ở đây, và sau đó, sẽ lèm bèm về Miller, “Thầy của Thầy”, tức triết gia PCT.

Dương Nghiễm Mậu: Thật chững chạc, thật cảm động...

Nói một cách khác, không có vụ di cư, không có tờ Sáng Tạo, không có Dương Nghiễm Mậu. Rượu Chưa Đủ "chưa đủ", nó cần một, hay nhiều hình ảnh khác nữa để tự khẳng định, để hoàn tất: chúng bổ túc cho nhau, những đứa con tư sinh của một miền đất. Nói rõ hơn, Dương Nghiễm Mậu là một "dị bản", của một Thanh Tâm Tuyền quá trí thức, quá Tây-phương, quá say mê Malraux... Một Thanh Tâm Tuyền "khác", khô, cứng, thật chững chạc, nhưng cũng thật cảm động... Nguyễn Đình Toàn, lại một Thanh Tâm Tuyền khác nữa, một bên là mặt trời, một bên là bóng đêm, chúng bổ túc cho nhau. Dẫn chứng quá nhiều: Chị Em Hải (Nguyễn Đình Toàn) là một dị bản của kịch Ba Chị Em (Thanh Tâm Tuyền). Đêm Lãng Quên, truyện ngắn được Võ Phiến tuyển chọn ở hải ngoại, khi viết về những tác giả Miền Nam, thoát thai từ một truyện ngắn của Thanh Tâm Tuyền, tôi không còn nhớ tên, viết về ông già gác dan, (gác ga-ra?) cho cặp nhân tình tạm trú, cuối cùng bị gã con trai nện cho sặc máu mũi, gục xuống một đống... Trước khi bỏ đi, gã thét cô bồ: lột cái xú-chiêng ra, ném lên mặt khứa lão! Mùi vị đàn bà, cuộc tình hối hả... làm ông lão tỉnh dậy, thấy mình đang ở Thiên Đàng, hay phía bên kia Địa Ngục (Chiến Tranh)... Hãy so sánh với Đêm Lãng Quên, về một già muốn làm con ong hút nhị từ cô gái.... Chất hung bạo trong thơ Thanh Tâm Tuyền tràn lan ra văn. Ở Nguyễn Đình Toàn, lại là sự tắt nghẹn, hết hơi, của những bóng dáng đàn bà, không còn đủ hơi sức, để kéo lê, thân xác của chính họ: Cái Chết, Cái Sống đều thoi thóp như nhau. Bóng dáng của Thần Chết, của Chiến Tranh lảng vảng ở trước, hoặc sau đời sống: nó vắng mặt, như một từ chối quyết liệt, bởi những con người đứng bên lề...

Nói một cách khác, không có vụ di cư, không có tờ Sáng Tạo, không có Dương Nghiễm Mậu. Rượu Chưa Đủ "chưa đủ", nó cần một, hay nhiều hình ảnh khác nữa để tự khẳng định, để hoàn tất: chúng bổ túc cho nhau, những đứa con tư sinh của một miền đất. Nói rõ hơn, Dương Nghiễm Mậu là một "dị bản", của một Thanh Tâm Tuyền quá trí thức, quá Tây-phương, quá say mê Malraux... Một Thanh Tâm Tuyền "khác", khô, cứng, thật chững chạc, nhưng cũng thật cảm động... Nguyễn Đình Toàn, lại một Thanh Tâm Tuyền khác nữa, một bên là mặt trời, một bên là bóng đêm, chúng bổ túc cho nhau. Dẫn chứng quá nhiều: Chị Em Hải (Nguyễn Đình Toàn) là một dị bản của kịch Ba Chị Em (Thanh Tâm Tuyền). Đêm Lãng Quên, truyện ngắn được Võ Phiến tuyển chọn ở hải ngoại, khi viết về những tác giả Miền Nam, thoát thai từ một truyện ngắn của Thanh Tâm Tuyền, tôi không còn nhớ tên, viết về ông già gác dan, (gác ga-ra?) cho cặp nhân tình tạm trú, cuối cùng bị gã con trai nện cho sặc máu mũi, gục xuống một đống... Trước khi bỏ đi, gã thét cô bồ: lột cái xú-chiêng ra, ném lên mặt khứa lão! Mùi vị đàn bà, cuộc tình hối hả... làm ông lão tỉnh dậy, thấy mình đang ở Thiên Đàng, hay phía bên kia Địa Ngục (Chiến Tranh)... Hãy so sánh với Đêm Lãng Quên, về một già muốn làm con ong hút nhị từ cô gái.... Chất hung bạo trong thơ Thanh Tâm Tuyền tràn lan ra văn. Ở Nguyễn Đình Toàn, lại là sự tắt nghẹn, hết hơi, của những bóng dáng đàn bà, không còn đủ hơi sức, để kéo lê, thân xác của chính họ: Cái Chết, Cái Sống đều thoi thóp như nhau. Bóng dáng của Thần Chết, của Chiến Tranh lảng vảng ở trước, hoặc sau đời sống: nó vắng mặt, như một từ chối quyết liệt, bởi những con người đứng bên lề...

“Có người đến hỏi tôi:

Có đi ra ngoại quốc không? Tôi đã trả

lời dứt khoát: Tôi sống và chết tại nơi này.

Người ấy hỏi: Anh chấp nhận sống chung với người Cộng Sản? Tôi

nói: Tôi không phải là một con chó

để nay sống với chủ này, mai sống với chủ khác chỉ vì

miếng xương chúng liệng ra. Tôi tin tưởng con đường tôi

đi. Có một nơi là lẽ phải và ánh sáng.

Có một nơi là lẽ trái và bóng tối.

Có trắng và đen không thể nhập nhằng được. Nếu

tôi có chết chăng nữa, điều ấy tôi không ân

hận. Lịch sử đã chứng minh rằng: Nhiều khi cái chết là

một điều tốt hơn là sống. Chết đi cho người khác sống,

cho lẽ phải và sự thực, sống chết như thế cần thiết. Tôi

bình tĩnh với quyết tâm đó”. (1)

Note:

Đâu có phải chỉ

1 DNM chọn ở lại. Gần như chẳng 1 ai chọn “đi”, trừ những người

không thể ở lại.

Đọc những dòng trên, như không phải của DNM. Lớn lối quá!

Đọc những dòng trên, như không phải của DNM. Lớn lối quá!

NQT

Cách viết của DNM, thái

độ của anh với cuộc chiến, một cách nào đó,

hợp với những dòng của tờ Người Kinh Tế, khi tưởng

niệm Boris Nemtsov, người hùng Nga Xô vừa bị giết hại:

Ông ta sinh ra không phải để hận thù, hay làm người hùng. Ông ta có những giấc mơ, nhưng không hề có ý trở thành 1 chiến sĩ chống lại chính quyền, nhà nước phát xít. Ông ta giản dị là 1 người tốt.

Ông ta sinh ra không phải để hận thù, hay làm người hùng. Ông ta có những giấc mơ, nhưng không hề có ý trở thành 1 chiến sĩ chống lại chính quyền, nhà nước phát xít. Ông ta giản dị là 1 người tốt.

Đúng là thái

độ của DNM trong cuộc chiến.

Nên nhớ, chỉ đến những ngày tháng cuối cùng của cuộc chiến, anh mới thực sự nhập cuộc, qua vai trò 1 ký sự gia, hay ký giả, hay ký giả chiến trường.

Nên nhớ, chỉ đến những ngày tháng cuối cùng của cuộc chiến, anh mới thực sự nhập cuộc, qua vai trò 1 ký sự gia, hay ký giả, hay ký giả chiến trường.

He was not born for hatred or

heroics. He had dreams, but had never intended to become a fighter

against state-sponsored fascism. He was simply a good man: too

good, in the end, for the country and the times he lived in. +

Obituary: Boris Nemtsov

DNM

gần như chưa từng ngồi Quán Chùa, như Gấu còn

nhớ được. Anh hay ngồi ở Cà Phê Thái Chi, nơi

Gấu cũng hay ngồi, rồi tới thằng em của Gấu cũng hay ngồi, khi Gấu gần

như quên hẳn nó. Con đường này, nổi tiếng, vì

Thái Chi, quán hủ tíu phía bên kia

đường đối diện Thái Chi, và 1 quán chuyên bán

ô mai. Đầu vô, đường Đinh Tiên Hoàng, rạp Đa

Kao, đầu ra Trần Quang Khải, quẹo trái, đi vài bước là

đụng Cà Phê Bà Lê Chân của Huy Tưởng

Kafka in the

21st century

A new exhibition paints the war on terror as a bureaucratic nightmare

A new exhibition paints the war on terror as a bureaucratic nightmare

Fiction

Life and afterlife

The surprising late literary flowering of John Maxwell Coetzee

Aug 6th 2016 | From the print edition

http://www.economist.com/news/books-and-arts/21703348-surprising-late-literary-flowering-john-maxwell-coetzee-life-and-afterlife

Life and afterlife

The surprising late literary flowering of John Maxwell Coetzee

Aug 6th 2016 | From the print edition

http://www.economist.com/news/books-and-arts/21703348-surprising-late-literary-flowering-john-maxwell-coetzee-life-and-afterlife

The Schooldays

of Jesus. By J.M. Coetzee. Harvill Secker; 260 pages; £17.99.

To be published in America by Viking in February 2017; $27.

Những

ngày đi học của Chúa Kitô: Bông

hoa nở muộn của 1 thiên tài già hai lần Booker,

một lần Nobel.

Hai lần Booker? Biết đâu, ba?

Nhờ Coetzee, Gấu biết tới Walter Benjamin, qua bài viết của ông trên tờ NYRB, Tin Văn đã từng dịch, “Những Kỳ Tích của WB”. Chính là nhờ những người như ông, vừa viết giả tưởng vừa viết phê bình, Gấu ngộ ra, phê bình chính là 1 dạng giả tưởng cực cao, chính nó, ở vào những bước ngoặt của lịch sử, đổi hẳn dòng chảy của văn học. Câu phán khủng khiếp của WB, lịch sử phải viết từ đáy, thay vì từ đỉnh, làm đổi hẳn cách trao giải thưởng Nobel, với những tác giả được giải sau đó, như Cao Hành Kiện, Kertesz, Jelinek….

Hai lần Booker? Biết đâu, ba?

Nhờ Coetzee, Gấu biết tới Walter Benjamin, qua bài viết của ông trên tờ NYRB, Tin Văn đã từng dịch, “Những Kỳ Tích của WB”. Chính là nhờ những người như ông, vừa viết giả tưởng vừa viết phê bình, Gấu ngộ ra, phê bình chính là 1 dạng giả tưởng cực cao, chính nó, ở vào những bước ngoặt của lịch sử, đổi hẳn dòng chảy của văn học. Câu phán khủng khiếp của WB, lịch sử phải viết từ đáy, thay vì từ đỉnh, làm đổi hẳn cách trao giải thưởng Nobel, với những tác giả được giải sau đó, như Cao Hành Kiện, Kertesz, Jelinek….

JUDGING the Man Booker prize, the world’s best-known annual award for fiction in English, involves reading a novel a day—every day—for more than six months. The initial distillation of this compulsive word-brew is the longlist, 13 books which are known collectively as the Man Booker dozen and are the first indication of what the judging panel is thinking. A crowd of famous authors failed to make the cut this year, from Edna O’Brien to Don DeLillo. Instead, the longlist, announced on July 27th, included three tiny independent publishers and four first novels (all virtually unknown). One was written in a VW camper van, a sign perhaps that the judges were looking for authors and editors who live outside the mainstream.

So it came as something of a surprise that the list also included an old, if not elderly, hand, J.M. Coetzee. A Nobel laureate who has twice won the Man Booker (in 1983 for “The Life & Times of Michael K” and again in 1999 for “Disgrace”) and been longlisted three times more, Mr Coetzee is almost two decades older than any of his colleagues on the list. At an age when most people have retired to an armchair, he finds himself not so much making a late dash as accelerating on to a whole new literary motorway.

In 2009, when he was about to be 70, Mr Coetzee wrote two letters to Paul Auster, a New York novelist, outlining his ideas about “late style”. He saw the artist’s life as having two, perhaps three stages. “In the first you find, or pose for yourself, a great question. In the second you labour away at answering it. And then, if you live long enough, you come to a third stage, when the aforesaid great question begins to bore you, and you need to look elsewhere.” By then, as an Irish literary critic, Fintan O’Toole, pointed out, Mr Coetzee had turned his back on his “great question”, man’s capacity for cruelty and the future of his native South Africa, the setting for his two Man Booker winners. He had also just finished “Summertime”, an autobiographical novel that appeared to free him to make a fresh literary start.

The result, “The Childhood of Jesus”, Mr O’Toole wrote in the New York Review of Books, was “not so much a late work as a posthumous publication…a writer’s afterlife, Coetzee after Coetzee.” The main character, Simón, explains to Davíd, the small boy he has taken under his wing: “After death there is always another life…We human beings are fortunate in that respect.” The novel ends with the family on the run.

Readers, including Joyce Carol Oates who has a lifetime of difficult reading behind her, were gripped by the vestigial Bible tale and captivated by the spare writing style, even as they were bemused at the lack of conventional narrative landmarks and the fact that this so-called allegory turned out to be nothing of the kind. Mr Coetzee’s new book aims to take the story on. “The Schooldays of Jesus” is not out until later this month, so the Man Booker judges are among the few who have read it. What was it that so impressed them?

Davíd and his parents have taken refuge in another town. In need of employment, they are taken in on a farm and work as common labourers. The boy is naturally clever—and wilful—with ideas of his own. “He believes he has powers,” his father tells a friend. “As you can imagine, it is not easy to teach him.” The owners of the farm, three sisters, offer to pay for his education. Having failed to thrive in an ordinary school, the boy is sent to the Academy of Dance, which is devoted to “the training of the soul through music”.

Loose biblical associations are threaded throughout: a census is about to be held, the family meets many sinners, listens to parables and discusses sin, guilt, redemption and how miscreants should be treated. But the central issue of this novel and its predecessor is one that philosophers have pondered for centuries: what makes us human, and is there more to life than existence on this planet? People have feet of clay, but even the most earthbound can be transported by music, passion, poetry and the possibility of a next life—if only they find the key. Freed from literary convention, Mr Coetzee writes not to provide answers, but to ask great questions.

Will he become the first writer to win the Man Booker prize three times? Perhaps not this year. But that may not trouble him. Mr Coetzee is a writer; writing is what he does best. He is still having fun doing it and, at 76, he may not ask for more.

“Những ngày đi học của Christ”, như Mr O’Toole điểm, trên NYRB, thì không hẳn là 1 tác phẩm muộn, 1 di cảo…. đúng hơn, nó là cuộc đời sau của một nhà văn, Coetzee sau Coetzee.

Nhân vật chính Simon giải thích cho chú bé Sam, “sau cái chết luôn luôn có 1 đời khác, Chúng ta, con người may mắn ở chỗ đó.”

May mắn?

Số báo văn học mới nhất của Tẩy, cũng là về đề tài này, về “cái gọi là” sau đời, post-human, thêm đời, l’homme augmenté, xuyên đời, transhumanisme, và 1 bài viết trong số báo, coi, đây là 1 hiện tượng hư vô, nihilism, nếu chỉ nhắm vào khía cạnh thách đố sinh học, kéo dài tuổi thọ bằng cách thay thế tim gan phèo phổi…

Cioran cũng đã từng đặt ra vấn nạn này, và ông coi là vô nhân, vô đạo đức. "Hư vô, toàn trị mềm"... xuyên nhân bản hy vọng con người vượt qua mức trăm năm trong cõi người ta, vượt quá giới hạn sinh học, để sống hài hòa, s'ybrider, với máy móc.

Đi tìm phê bình

gia Mít

Cái

tên đệ tử Lữ Phương, là kẻ chịu ơn TTT và GCC.

Thay vì biết ơn, hắn đưa cả hai vô danh sách 12 nhà

văn phản động, đồi trụy. Không chỉ thế. Ra hải ngoại, sớm sủa,

trở thành 1 nhà văn nổi tiếng, hắn viết sách, trong

đó chửi GCC, không biết bao nhiêu lần, không

làm sao nhớ nổi, cái “gì gì” trong cõi

ký ức trong xanh.

Tại sao hắn lại làm như thế?

Tên Lang Băm, GCC đâu biết là thằng củ xê nào [từ này Duyên Anh & Thương Sinh ban cho GCC], vậy mà cũng chửi, giọng đầy hằn học.

Đây là vấn đề liên quan đến đạo hạnh, đẳng cấp, sống sót, đúng như Milosz phán, khi viết về Brodsky, như Brodsky, khi viết về Mandelstam.

Bản thân những tên này, chúng tự biết, chúng không thể viết được cái thứ mà chúng mong viết được.

Mỹ là mẹ của đạo hạnh, là như thế.

TTT, trong Thơ Ở Đâu Xa, 1 bi khúc, như NL gọi, tặng thơ rất nhiều người, những bạn tù của ông, những kẻ đồng hội, đồng thuyền, như ông gọi. Khi về đời, một số trong lũ này, thay vì cảm thấy thật là tuyệt vời, vì đã từng được là bạn tù của ông, không chỉ thế, mà còn được ông tặng thơ, thì lại rất ư là tức giận, khi thấy ông không uống cà phê nhớ bạn hiền với chúng!

Thế là trở mặt!

Đạo hạnh như kít làm sao làm thơ hay cho được!

Tại sao hắn lại làm như thế?

Tên Lang Băm, GCC đâu biết là thằng củ xê nào [từ này Duyên Anh & Thương Sinh ban cho GCC], vậy mà cũng chửi, giọng đầy hằn học.

Đây là vấn đề liên quan đến đạo hạnh, đẳng cấp, sống sót, đúng như Milosz phán, khi viết về Brodsky, như Brodsky, khi viết về Mandelstam.

Bản thân những tên này, chúng tự biết, chúng không thể viết được cái thứ mà chúng mong viết được.

Mỹ là mẹ của đạo hạnh, là như thế.

TTT, trong Thơ Ở Đâu Xa, 1 bi khúc, như NL gọi, tặng thơ rất nhiều người, những bạn tù của ông, những kẻ đồng hội, đồng thuyền, như ông gọi. Khi về đời, một số trong lũ này, thay vì cảm thấy thật là tuyệt vời, vì đã từng được là bạn tù của ông, không chỉ thế, mà còn được ông tặng thơ, thì lại rất ư là tức giận, khi thấy ông không uống cà phê nhớ bạn hiền với chúng!

Thế là trở mặt!

Đạo hạnh như kít làm sao làm thơ hay cho được!

Sách

&

Báo

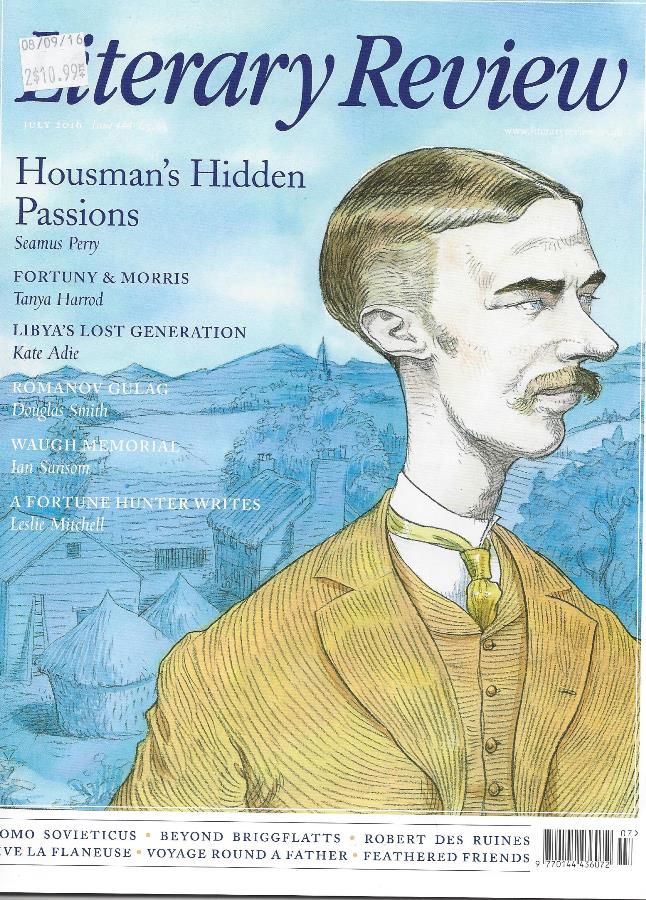

https://literaryreview.co.uk/

Tờ Điểm Sách này của Ăng Lê, khác nhiều lắm, so với Mẽo, hoặc Tẩy.

Mắc hơn nữa!

Until recently, Svetlana Alexievich was little known outside the world of Russian studies. That changed last October, when she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, becoming the first ever Belarussian and the first non-fiction writer since Winston Churchill to receive it. Since the start of her publishing career in the mid 1980s, her theme has been the tragic past of the former Soviet Union, as recounted by multiple individuals in their own voices. Hundreds of subjects are interviewed at length, some repeatedly and over many years. The resulting transcripts are edited down to anything from a one-line snippet to a chapter-length monologue and presented to the reader with minimal biographical information and little or no authorial comment.

Best known abroad of Alexievich’s books is Zinky Boys, the title taken from the zinc coffins in which Soviet soldiers killed in the Soviet–Afghan War were transported home. Most recent is Voices from Chernobyl, which gathers together first-hand accounts of the nuclear disaster. Ten years in the making, Second-Hand Time is her longest and most ambitious work to date. Her subject, she explains, is the Homo sovieticus or, pejoratively ‘sovok’, meaning someone ineradicably formed by the Soviet Union. ‘People who have come out of socialism’, she writes, ‘are both like and unlike the rest of humanity – we have our own lexicon, our own conceptions of good and evil, our heroes and martyrs. We have a special relationship with death.’

RUSSIA & CRIMEA

32 Douglas Smith

The House of the Dead· Siberian Exile under the Tsars

Daniel Beer

33 Anna Reid

Second-Hand Time: The Last of the Soviets

Svetlana Alexievich

35 Donald Rayfield

Crimea: A History Neil Kent· The Crimean Tatars: From

Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest Brian Glyn Williams

Bài điểm cuốn Second-Hand Time, tuyệt. GCC mua số báo vì bài điểm này.

Trong khi chờ đợi, độc giả TV đọc đỡ bài trên báo Mẽo

Book Review | Nonfiction

‘Secondhand Time,’ by Svetlana Alexievich

By ADAM HOCHSCHILDMAY 27, 2016

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/29/books/review/secondhand-time-by-svetlana-alexievich.html?_r=0

Số này còn có bài điểm cuốn thứ nhì, sau cuốn Kẻ Phản Thùng của anh Mít Mẽo được Pulitzer: Chẳng có gì chết đi, Nothing Ever Dies.

Người điểm là Jonathan Mirsky.

A Right Way to Remember?

Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the memory of War

Cách đọc, của ông, cũng cách viết về cuộc chiến Mít, của Viet Thanh Nguyen, theo GCC, lỗi thời rồi.

Trong bài điểm cuốn sách của Bà Nobel, có 1 câu thật tuyệt, cho thấy cái lỗi thời của cả hai:

Chỉ 1 tên Xô Viết mới hiểu được 1 tên Xô Viết khác.

Only a Soviet person can understand another Soviet person

Phải 1 tên Bắc Kít thì mới hiểu 1 tên Bắc Kít khác!

Ngay từ 1954, Việt Gian đã cảnh cáo Vẹm, coi chừng con quỉ nơi chuồng lợn!

https://www.flickr.com/photos/13476480@N07/28904817836/

Cách đúng để nhớ?

Theo Mirsky, VTN có ba cách, Nguyen actually perceives three kinds of memory of the war.

Vẫn thiếu 1 cách.

Đúng hơn, thiếu yếu tố Tẫu.

Ông chủ không biết trong nhà của mình có gì, cô tớ gái trong Y sĩ đồng quê của Kafka, phán.

Thiếu con quỉ nơi chuồng heo.

Khi Hồ tới Moscow, đúng thời gian Xì thanh trừng đám cựu trào.

"Cái gì" khiến Xì tha mạng Hồ?

Xì tha Hồ, vì đã giao tính mạng Hồ, và số phận xứ Mít, cho.... con quỉ nơi chuồng heo!

Svetlana Alexievich has said that when she assembles one of her remarkable collections of oral histories she is constructing a “novel in voices.” In this latest book, one voice is of a woman who seems to have stepped out of a tale by Chekhov. With three children, she is married to a good man who loves her. But then, on the strength of a photograph, she decides that someone else is the man she really loves — whom she once saw in a dream. He, however, is in prison, serving a life sentence for murder.

To top it off, his prison is a converted monastery, with walls five feet thick, on an island in an isolated northern lake. She divorces her husband, abandons her children, marries the prisoner, whom she is seldom allowed to see, and finds a low-paying job nearby. Then they quarrel and she disappears.

But recent history has added a twist Chekhov could not have imagined. This prisoner committed his murder in what was then still the Soviet Union. If he is ever released, it will be into a radically different Russia, where, as one of Alexievich’s interview subjects says, “the discovery of money hit us like an atom bomb.” It is the contrast between these two countries — as felt by people living in the second but remembering the first — that is the subject of “Secondhand Time,” her first book to appear in English since she won the Nobel Prize in Literature last year. (It appeared in Russia in 2013.)

As in many a Chekhov story, few of the people she records are happy. “There is something in the Russian spirit,” she said in her Nobel lecture, “that compels it to try to turn . . . dreams into reality.” This was true of the woman who loved the prisoner, and it was also true of the Russian people as a whole, who lived, for some 70 years, in a society ostensibly based on a dream of human brotherhood that turned out to be something catastrophically different.

Among believers in the dream of Soviet Communism, Alexievich finds a nostalgia for its achievements and a deep sense of loss. Quite poignantly, she zeros in from several angles (press reports, official documents, an interview with someone who knew him) on Marshal Sergey Akhromeyev, who was said to be a supporter of the 1991 coup attempt against Mikhail Gorbachev, and who hanged himself in his Kremlin office when it failed. “I cannot go on living,” he wrote, “while my Fatherland is dying and everything I heretofore considered to be the meaning of my life is being destroyed.” In a final humiliation, symbolic of the crass market society replacing Akhromeyev’s beloved Communism, his grave was robbed and his uniform, cap and medals — all of which now fetch high prices from antique dealers — were taken.

Alexievich also describes another military suicide. Anyone who spent time in the old Soviet Union will remember the immense honors lavished upon World War II veterans. One, Timeryan Zinatov, won a medal for his role in defending the famous fortress at Brest, and then fought through the rest of the war. A construction worker in Siberia, he returned to the fortress, the scene of his moment of glory, every year. In 1992, shocked by the new Russia, where brand name fashion accessories mean more than war medals, he came back one last time to Brest, which by then was in a different country, Belarus. Then he threw himself under a train, leaving a message asking to be buried in the fortress.

Continue reading the main story

It’s more surprising that Alexievich finds similar true believers among those who suffered the very worst Soviet fury. A onetime factory director, for instance, had been arrested during Stalin’s Great Purge of the late 1930s, beaten, tortured, hung “from hooks like it was the Middle Ages!” After the interrogator is done with you, he says, “you’re nothing but a piece of meat . . . lying in a pool of urine.” Luckier than millions, he was released after a year: “It had been a mistake.”

In the army in World War II, he ran into his former interrogator, who now said to him, “We share a Motherland.” The Soviet dream, as much about patriotism for the Motherland as about utopia, offered a universe of certainties despite “mistakes,” even to those who were its victims. For this factory director, in his retirement, tells Alexievich that he feels “surrounded by strangers” in the new Russia. “When I go into my grandchildren’s room, everything in there is foreign: the shirts, the jeans, the books, the music. . . . Their shelves are lined with empty cans of Coke and Pepsi. Savages!” He finishes: “I want to die a Communist. That’s my final wish.”

Despite their oppressive “mistakes,” empires of all kinds keep a lid on things, and one of the tragedies of the post-Soviet world — as it was of post-British India and of the post-Tito former Yugoslavia — is the upwelling of long-contained ethnic and religious strife.

Among those whose voices Alexievich brings us is an Armenian woman married to an Azerbaijani. In Soviet times, they lived in Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku, “my favorite city . . . in spite of everything! . . . I don’t remember any discussion of . . . nationalities. The world was divided up differently: Is someone a good or bad person, are they greedy or kind?” To welcome spring, everyone in her apartment building — Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Georgians, Russians, Ukrainians — would share food around a long table in the courtyard. Then, as the Soviet Union collapsed, demagogues everywhere whipped up tensions. The bodies of murdered Armenians appeared on the streets. Azerbaijanis attacked her husband, beating him with iron rods, for being married to an “enemy.” She asked her mother, “Mama, did you notice that the boys in the courtyard have stopped playing war and started playing killing Armenians?” When she fled for her life to Moscow, her husband’s family refused to pass on her phone messages to him — and claimed to her that he had remarried. Years later, he finally made it to Moscow too, where they now live, illegally and traumatized.

I have a few minor quibbles with the way Alexievich weaves her rich tapestry of voices. Although the interviews are grouped by decades (1991-2001, 2002-12), she does not tell us whether she talked to someone in 1991, when the enfeebled Soviet Union was still alive, or in 2001, when it was 10 years dead. She uses many ellipses in each paragraph, which show how a monologue has been edited but give it a slightly spacey and disjointed feel. And unlike her distinguished American counterpart Studs Terkel, who sometimes set the scene in a headnote to an interview, she gives us little or no background on her subjects, usually just something as cryptic as “Olga V., surveyor, 24.” And when she does provide a rare headnote, her own editorial voice can intrude: “Sometimes I think that pain is a bridge between people, a secret connection; other times, it seems like an abyss.” There is no need for this: She has successfully bridged the abyss.

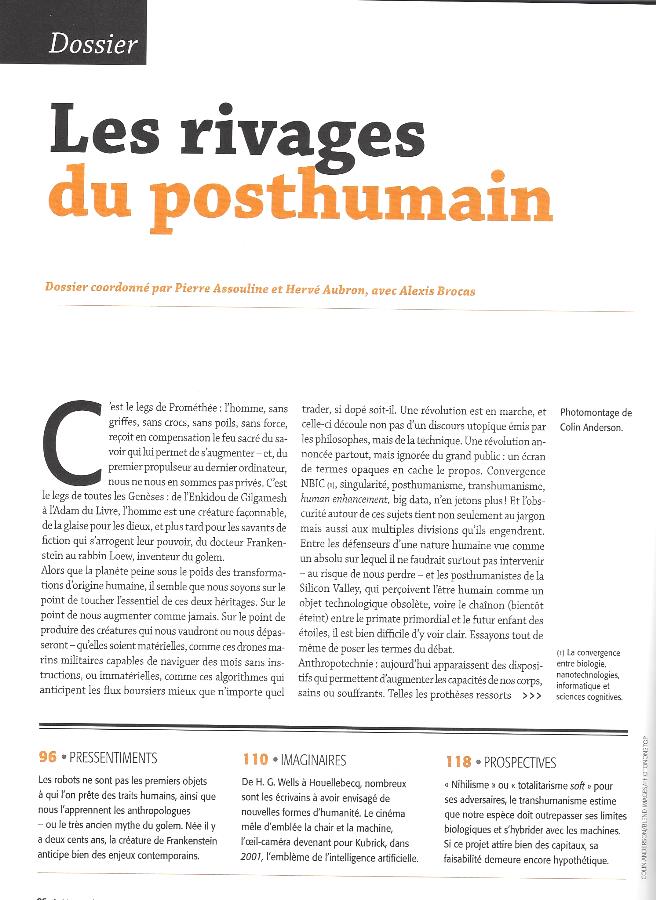

Hậu Nhân Bản Chủ Nghĩa: SOS Latin Grec

Hai số báo trên, cùng 1 đề tài: Phép Lạ Hy Lạp

http://www.magazine-litteraire.com/critique/greene-la-gr%C3%A2ce-intranquille-0

Greene, la grâce intranquille

Par Pierre Assouline dans Magazine

Littéraire 569

daté juillet-août 2016 - 1375 mots

Converti au catholicisme, le Britannique

conjuguait la foi et le doute : il fut toujours hanté par le vertige

de la déloyauté.

Un retour en grâce des romans de Graham Greene en librairie serait un signe des temps. Un peu comme si Mauriac et Bernanos surgissaient dans la liste des meilleures ventes. Tous trois étaient baptisés « écrivains catholiques », label que le Britannique rejetait : « On peut être écrivain et catholique sans être écrivain catholique », disait celui qui avait déserté la foi anglicane des siens à 22 ans pour trouver refuge sur l'autre rive, du côté des minoritaires jadis persécutés. Dieu, la Grâce, le Salut, dans cet ordre et sans oublier les majuscules : La Puissance et la Gloire, Le Fond du problème et La Fin d'une liaison n'ont cessé de tourner autour, en un temps où nombre de lecteurs à travers le monde partageaient le grand souci métaphysique, sans oublier Rocher de Brighton, tout aussi travaillé par l'intranquillité spirituelle. Depuis, il semble que l'inquiétude ait modifié ses paramètres, ce qui ne va pas sans retirer une certaine profondeur à la fiction contemporaine, l'adultère ne conduisant plus à la sainteté. Même le constant éloge de la déloyauté risque fort de paraître inactuel en nos temps de surveillance des moeurs et des esprits par le politiquement correct. N'empêche que la souffrance issue de la trahison tourmente l'essentiel de l'oeuvre de Graham Greene. L'écrivain nous entraîne dans le labyrinthe des couples illégitimes, de l'amour à la haine en passant par la jalousie, le spectre de l'ennui, l'excitation du danger, les délires d'interprétation, et ce doute incessant qui corrode les âmes les mieux armées plus profondément que toute culpabilité.

La Fin d'une liaison est l'un de ses romans dont l'empreinte sur le lecteur est la plus prégnante. C'est le troisième volet d'une manière de trilogie sur la question de la grâce divine. Un homme et une femme, à Londres, pendant la guerre. Elle est mariée à un fonctionnaire civil, il est écrivain et célibataire ; leur rencontre est un coup de foudre. Un jour, alors qu'ils se retrouvent dans une chambre d'hôtel, une bombe allemande leur tombe dessus. Pendant quelques minutes, elle est convaincue qu'il est mort sous les décombres. Lorsqu'il réapparaît, elle met un terme à leur relation, sans explication. Craignant qu'elle ait changé d'amant, il la fait suivre par un détective : en fait, elle se rend régulièrement chez un ecclésiastique... Pour la première fois, Graham Greene usait du « je » dans un roman. À une rupture dans sa vie devait correspondre une rupture dans son style. Il savait qu'on n'est jamais mieux masqué que lorsqu'on écrit à la première personne. L'histoire de cette folle passion amoureuse était la sienne. À sa parution, en 1951, le roman était dédié à une mystérieuse « C. ». Après la mort de l'écrivain, des biographes révéleront qu'elle s'appelait Catherine, qu'elle était l'épouse de lord Walston, haute personnalité travailliste ; elle fut sa maîtresse de 1946 à 1957, mais jamais ils ne se déprirent l'un de l'autre, leur correspondance jusqu'à la toute fin en témoigne. Il ne l'aimait pas : il l'adorait. Quand Catherine disparut, il envoya un message de condoléances à son mari, lequel répondit : « Vous lui avez donné quelque chose, j'ignore quoi, que personne d'autre ne lui avait donné. » Elle-même, dans sa dernière lettre, lui avouait : « Il n'y a jamais eu quelqu'un comme toi dans ma vie. » On s'en doutait, mais on en a la confirmation : sa vie fut son meilleur roman.

Vingt-six romans et un grand nombre de nouvelles, traduits en quarante langues, entre 1926 et 1990. À quoi il convient d'ajouter des milliers d'articles, une correspondance très fournie, le noircissement quotidien de petits carnets et d'agendas Hermès. Graham Greene, dont rien ni personne ne bridait la curiosité, a touché à tous les genres : roman policier (Un Américain bien tranquille), roman de divertissement (Notre agent à La Havane), roman d'espionnage (Le Facteur humain), thriller (Le Ministère de la peur), essai autobiographique (Une sorte de vie, Les Chemins de l'évasion), scénario (Le Troisième Homme), pamphlet (J'accuse), lettre au courrier des lecteurs des grands journaux, une anthologie des plus savoureuses dans le registre de l'understatement (Avec mes sentiments les meilleurs), et jusqu'à l'interprétation de ses rêves (Mon univers secret). On allait faire l'impasse, impardonnable s'agissant d'un écrivain britannique, sur les nouvelles, dont il évoquait le goût comme « une boisson fraîche dans une bouche brûlante ». Le meilleur, et donc le plus troublant et le plus ambigu, y est reflété d'un écrivain qui admirait Dickens et Conrad, avant d'être lui-même admiré par John Le Carré ; c'est peu dire qu'il a inspiré ce dernier, du moins pour le tourment de la trahison.

On est ce qu'on reçoit et ce qu'on transmet à condition de créer son petit quelque chose dans l'intervalle. Graham Greene ne dissimulait pas que l'écriture était pour lui une thérapie. Le remords lui était si naturel qu'il continuait à remettre ses livres sur le métier après publication. D'une édition à l'autre, les corrections se poursuivaient, jusqu'à transformer le texte en palimpseste. Ses archives déposées à l'université d'Austin, Texas, pourraient être considérées comme faisant partie de ses oeuvres complètes tant elles sont riches et édifiantes. Avant de les verser, ou plutôt de les vendre aux Américains, il en conservait certaines chez lui, c'est-à-dire chez sa compagne française, Yvonne Cloetta, à Antibes. Il m'avait notamment montré dans un grand éclat de rire le dossier que le FBI avait constitué sur lui, le fichant tel un dangereux révolutionnaire. Conséquence moins drôle : alors que son nom était régulièrement évoqué dans les années 1950-1960 comme nobélisable, il était systématiquement barré en raison de sa réputation de « crypto-communiste ». Graham Greene aimait la France, qui le lui rendait bien. Les lecteurs faisaient fête à ses traductions et souvent aux films adaptés de ses romans. Une saga qui avait commencé le jour où, ayant reniflé le dernier Greene dans une librairie de Londres à la fin des années 1940, un jeune éditeur marseillais, un certain Robert Laffont, s'était présenté tout simplement au domicile de l'écrivain pour lui dire son désir de le publier en français et de signer un contrat, lequel fut tacitement renouvelé pendant des décennies. À la fin des années 1980, comme le romancier passait par Paris, l'éditeur lui fit la surprise d'organiser une projection privée sur grand écran du chef-d'oeuvre dont il avait été le scénariste : Le Troisième Homme de Carol Reed ; et, pour y avoir assisté assis entre l'un et l'autre, je puis témoigner de l'intensité de l'estime et de l'amitié qui lient parfois un auteur et son éditeur.

Greeneland ! L'intéressé détestait cette AOC qui nimbait son oeuvre. Pourtant, cet univers métaphysique, et même psychologique, se reconnaissait d'emblée. François Gallix, l'un de ses meilleurs connaisseurs, le ramasse ainsi : « Un arrière-plan très typé donnant une fausse impression de réalisme et dont la couleur locale n'est pas totalement absente, tout en étant très imprégné de symbolisme, avec des personnages entre deux âges, esseulés, à bout de course, aux vies souvent ratées - anti-héros solitaires qui sont amenés à faire des choix cruciaux tout en étant capables d'actes de courage. » Encore faut-il préciser qu'un mot clé ouvre la porte de ce monde gris, à la frontière entre le bien et le mal : seediness, que l'on rendrait improprement par « sordidité » ou « sordidisme ».

Pour avoir eu le privilège de passer une journée à bavarder avec lui à bâtons rompus, à l'écouter regretter d'être passé par Moscou sans avoir revu son ami, le traître Kim Philby, dénoncer les clowneries et ragots d'Anthony Burgess à son endroit, démentir qu'Orson Welles ait été l'auteur des dialogues les plus célèbres du Troisième Homme, ce que l'acteur s'attribuait publiquement (« Et pendant ce temps, qu'a inventé la Suisse ? Le coucou ! »), je me souviens notamment d'une phrase : « A novel is never what it is about. » Tout romancier devrait la garder à l'esprit, tout lecteur aussi : un roman, ce n'est pas un sujet, ça parle de tout autre chose que ce qui est annoncé. Bienvenue dans ce territoire de l'imaginaire aux frontières si floues, mais si prégnantes qu'il faut s'en échapper pour savoir qu'on y a été. Un monde où la déloyauté est une vertu, où tout se passe la nuit, où il pleut tout le temps et où celui qui tire les ficelles de l'histoire se fait toujours l'avocat du diable pour les individus hors limites.

Greene, Ân sủng đếch trầm lặng

PA đọc Graham Greene .

The

Virtue of Disloyalty, Đạo hạnh của Cái Bất Trung, một trong những nỗi nhức nhối của GGG,

và cũng còn là tít 1 bài viết/đáp

từ của ông, khi nhận giải thưởng Shakepeare Prize của Đại Học Hamburg,

6 June, 1969, có trong Reflections

Ui chao, không lẽ Sài Gòn, Khu Chợ Đũi, BHD, Quán Chùa..... của Gấu, thì cũng chỉ như một trong những tiệm sách cũ, như trên, của Greene?

Nhưng, giả như thế, thì lại càng tuyệt, tuyệt!

Bởi vì rõ ràng là, khi dịch Istanbul, Gấu cũng có cảm giác như vậy, không phải về những con phố của Istanbul của Pamuk, nhưng mà là của Sài Gòn. Những đoạn phóng bút, là về Sài Gòn, về BHD của Gấu, không phải về Istanbul, về BHD của Pamuk!

Ai điếu Elie Wiesel

https://literaryreview.co.uk/

Tờ Điểm Sách này của Ăng Lê, khác nhiều lắm, so với Mẽo, hoặc Tẩy.

Mắc hơn nữa!

Anna Reid

‘Things only ever got worse’

Second-Hand Time: The Last of Soviets

By Svetlana Alexievich (Translated by Bela Shayevich)

Fitzcarraldo Editions 695pp £14.99 order from our bookshop

Literary Review - Britain's best-loved Literary Magazine

‘Things only ever got worse’

Second-Hand Time: The Last of Soviets

By Svetlana Alexievich (Translated by Bela Shayevich)

Fitzcarraldo Editions 695pp £14.99 order from our bookshop

Literary Review - Britain's best-loved Literary Magazine

Until recently, Svetlana Alexievich was little known outside the world of Russian studies. That changed last October, when she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, becoming the first ever Belarussian and the first non-fiction writer since Winston Churchill to receive it. Since the start of her publishing career in the mid 1980s, her theme has been the tragic past of the former Soviet Union, as recounted by multiple individuals in their own voices. Hundreds of subjects are interviewed at length, some repeatedly and over many years. The resulting transcripts are edited down to anything from a one-line snippet to a chapter-length monologue and presented to the reader with minimal biographical information and little or no authorial comment.

Best known abroad of Alexievich’s books is Zinky Boys, the title taken from the zinc coffins in which Soviet soldiers killed in the Soviet–Afghan War were transported home. Most recent is Voices from Chernobyl, which gathers together first-hand accounts of the nuclear disaster. Ten years in the making, Second-Hand Time is her longest and most ambitious work to date. Her subject, she explains, is the Homo sovieticus or, pejoratively ‘sovok’, meaning someone ineradicably formed by the Soviet Union. ‘People who have come out of socialism’, she writes, ‘are both like and unlike the rest of humanity – we have our own lexicon, our own conceptions of good and evil, our heroes and martyrs. We have a special relationship with death.’

RUSSIA & CRIMEA

32 Douglas Smith

The House of the Dead· Siberian Exile under the Tsars

Daniel Beer

33 Anna Reid

Second-Hand Time: The Last of the Soviets

Svetlana Alexievich

35 Donald Rayfield

Crimea: A History Neil Kent· The Crimean Tatars: From

Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest Brian Glyn Williams

Bài điểm cuốn Second-Hand Time, tuyệt. GCC mua số báo vì bài điểm này.

Trong khi chờ đợi, độc giả TV đọc đỡ bài trên báo Mẽo

Book Review | Nonfiction

‘Secondhand Time,’ by Svetlana Alexievich

By ADAM HOCHSCHILDMAY 27, 2016

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/29/books/review/secondhand-time-by-svetlana-alexievich.html?_r=0

Số này còn có bài điểm cuốn thứ nhì, sau cuốn Kẻ Phản Thùng của anh Mít Mẽo được Pulitzer: Chẳng có gì chết đi, Nothing Ever Dies.

Người điểm là Jonathan Mirsky.

A Right Way to Remember?

Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the memory of War

Cách đọc, của ông, cũng cách viết về cuộc chiến Mít, của Viet Thanh Nguyen, theo GCC, lỗi thời rồi.

Trong bài điểm cuốn sách của Bà Nobel, có 1 câu thật tuyệt, cho thấy cái lỗi thời của cả hai:

Chỉ 1 tên Xô Viết mới hiểu được 1 tên Xô Viết khác.

Only a Soviet person can understand another Soviet person

Phải 1 tên Bắc Kít thì mới hiểu 1 tên Bắc Kít khác!

Ngay từ 1954, Việt Gian đã cảnh cáo Vẹm, coi chừng con quỉ nơi chuồng lợn!

https://www.flickr.com/photos/13476480@N07/28904817836/

Cách đúng để nhớ?

Theo Mirsky, VTN có ba cách, Nguyen actually perceives three kinds of memory of the war.

Vẫn thiếu 1 cách.

Đúng hơn, thiếu yếu tố Tẫu.

Ông chủ không biết trong nhà của mình có gì, cô tớ gái trong Y sĩ đồng quê của Kafka, phán.

Thiếu con quỉ nơi chuồng heo.

Khi Hồ tới Moscow, đúng thời gian Xì thanh trừng đám cựu trào.

"Cái gì" khiến Xì tha mạng Hồ?

Xì tha Hồ, vì đã giao tính mạng Hồ, và số phận xứ Mít, cho.... con quỉ nơi chuồng heo!

Đám

Mít, con cái Ngụy, lớn lên ở Mẽo, do cũng thuộc

nhóm thiểu số, bị khinh khi, ngay từ khi còn nhỏ, khi

còn đi học, phải vượt qua được cái mặc

cảm/bất hạnh này, thì mới viết lách được, theo

GCC.

SECONDHAND TIME

The Last of the Soviets

Thời gian xài rồi xài lại:

Kẻ Cuối Cùng của những tên Xô Viết

[Tạm dịch cái tít]

The Last of the Soviets

Thời gian xài rồi xài lại:

Kẻ Cuối Cùng của những tên Xô Viết

[Tạm dịch cái tít]

By Svetlana Alexievich

Translated by Bela Shayevich

470 pp. Random House. $30.

Translated by Bela Shayevich

470 pp. Random House. $30.

Svetlana Alexievich has said that when she assembles one of her remarkable collections of oral histories she is constructing a “novel in voices.” In this latest book, one voice is of a woman who seems to have stepped out of a tale by Chekhov. With three children, she is married to a good man who loves her. But then, on the strength of a photograph, she decides that someone else is the man she really loves — whom she once saw in a dream. He, however, is in prison, serving a life sentence for murder.

To top it off, his prison is a converted monastery, with walls five feet thick, on an island in an isolated northern lake. She divorces her husband, abandons her children, marries the prisoner, whom she is seldom allowed to see, and finds a low-paying job nearby. Then they quarrel and she disappears.

But recent history has added a twist Chekhov could not have imagined. This prisoner committed his murder in what was then still the Soviet Union. If he is ever released, it will be into a radically different Russia, where, as one of Alexievich’s interview subjects says, “the discovery of money hit us like an atom bomb.” It is the contrast between these two countries — as felt by people living in the second but remembering the first — that is the subject of “Secondhand Time,” her first book to appear in English since she won the Nobel Prize in Literature last year. (It appeared in Russia in 2013.)

As in many a Chekhov story, few of the people she records are happy. “There is something in the Russian spirit,” she said in her Nobel lecture, “that compels it to try to turn . . . dreams into reality.” This was true of the woman who loved the prisoner, and it was also true of the Russian people as a whole, who lived, for some 70 years, in a society ostensibly based on a dream of human brotherhood that turned out to be something catastrophically different.

Among believers in the dream of Soviet Communism, Alexievich finds a nostalgia for its achievements and a deep sense of loss. Quite poignantly, she zeros in from several angles (press reports, official documents, an interview with someone who knew him) on Marshal Sergey Akhromeyev, who was said to be a supporter of the 1991 coup attempt against Mikhail Gorbachev, and who hanged himself in his Kremlin office when it failed. “I cannot go on living,” he wrote, “while my Fatherland is dying and everything I heretofore considered to be the meaning of my life is being destroyed.” In a final humiliation, symbolic of the crass market society replacing Akhromeyev’s beloved Communism, his grave was robbed and his uniform, cap and medals — all of which now fetch high prices from antique dealers — were taken.

Alexievich also describes another military suicide. Anyone who spent time in the old Soviet Union will remember the immense honors lavished upon World War II veterans. One, Timeryan Zinatov, won a medal for his role in defending the famous fortress at Brest, and then fought through the rest of the war. A construction worker in Siberia, he returned to the fortress, the scene of his moment of glory, every year. In 1992, shocked by the new Russia, where brand name fashion accessories mean more than war medals, he came back one last time to Brest, which by then was in a different country, Belarus. Then he threw himself under a train, leaving a message asking to be buried in the fortress.

Continue reading the main story

It’s more surprising that Alexievich finds similar true believers among those who suffered the very worst Soviet fury. A onetime factory director, for instance, had been arrested during Stalin’s Great Purge of the late 1930s, beaten, tortured, hung “from hooks like it was the Middle Ages!” After the interrogator is done with you, he says, “you’re nothing but a piece of meat . . . lying in a pool of urine.” Luckier than millions, he was released after a year: “It had been a mistake.”

In the army in World War II, he ran into his former interrogator, who now said to him, “We share a Motherland.” The Soviet dream, as much about patriotism for the Motherland as about utopia, offered a universe of certainties despite “mistakes,” even to those who were its victims. For this factory director, in his retirement, tells Alexievich that he feels “surrounded by strangers” in the new Russia. “When I go into my grandchildren’s room, everything in there is foreign: the shirts, the jeans, the books, the music. . . . Their shelves are lined with empty cans of Coke and Pepsi. Savages!” He finishes: “I want to die a Communist. That’s my final wish.”

Despite their oppressive “mistakes,” empires of all kinds keep a lid on things, and one of the tragedies of the post-Soviet world — as it was of post-British India and of the post-Tito former Yugoslavia — is the upwelling of long-contained ethnic and religious strife.

Among those whose voices Alexievich brings us is an Armenian woman married to an Azerbaijani. In Soviet times, they lived in Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku, “my favorite city . . . in spite of everything! . . . I don’t remember any discussion of . . . nationalities. The world was divided up differently: Is someone a good or bad person, are they greedy or kind?” To welcome spring, everyone in her apartment building — Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Georgians, Russians, Ukrainians — would share food around a long table in the courtyard. Then, as the Soviet Union collapsed, demagogues everywhere whipped up tensions. The bodies of murdered Armenians appeared on the streets. Azerbaijanis attacked her husband, beating him with iron rods, for being married to an “enemy.” She asked her mother, “Mama, did you notice that the boys in the courtyard have stopped playing war and started playing killing Armenians?” When she fled for her life to Moscow, her husband’s family refused to pass on her phone messages to him — and claimed to her that he had remarried. Years later, he finally made it to Moscow too, where they now live, illegally and traumatized.

I have a few minor quibbles with the way Alexievich weaves her rich tapestry of voices. Although the interviews are grouped by decades (1991-2001, 2002-12), she does not tell us whether she talked to someone in 1991, when the enfeebled Soviet Union was still alive, or in 2001, when it was 10 years dead. She uses many ellipses in each paragraph, which show how a monologue has been edited but give it a slightly spacey and disjointed feel. And unlike her distinguished American counterpart Studs Terkel, who sometimes set the scene in a headnote to an interview, she gives us little or no background on her subjects, usually just something as cryptic as “Olga V., surveyor, 24.” And when she does provide a rare headnote, her own editorial voice can intrude: “Sometimes I think that pain is a bridge between people, a secret connection; other times, it seems like an abyss.” There is no need for this: She has successfully bridged the abyss.

Hậu Nhân Bản Chủ Nghĩa: SOS Latin Grec

Hai số báo trên, cùng 1 đề tài: Phép Lạ Hy Lạp

http://www.magazine-litteraire.com/critique/greene-la-gr%C3%A2ce-intranquille-0

Greene, la grâce intranquille

daté juillet-août 2016 - 1375 mots

Un retour en grâce des romans de Graham Greene en librairie serait un signe des temps. Un peu comme si Mauriac et Bernanos surgissaient dans la liste des meilleures ventes. Tous trois étaient baptisés « écrivains catholiques », label que le Britannique rejetait : « On peut être écrivain et catholique sans être écrivain catholique », disait celui qui avait déserté la foi anglicane des siens à 22 ans pour trouver refuge sur l'autre rive, du côté des minoritaires jadis persécutés. Dieu, la Grâce, le Salut, dans cet ordre et sans oublier les majuscules : La Puissance et la Gloire, Le Fond du problème et La Fin d'une liaison n'ont cessé de tourner autour, en un temps où nombre de lecteurs à travers le monde partageaient le grand souci métaphysique, sans oublier Rocher de Brighton, tout aussi travaillé par l'intranquillité spirituelle. Depuis, il semble que l'inquiétude ait modifié ses paramètres, ce qui ne va pas sans retirer une certaine profondeur à la fiction contemporaine, l'adultère ne conduisant plus à la sainteté. Même le constant éloge de la déloyauté risque fort de paraître inactuel en nos temps de surveillance des moeurs et des esprits par le politiquement correct. N'empêche que la souffrance issue de la trahison tourmente l'essentiel de l'oeuvre de Graham Greene. L'écrivain nous entraîne dans le labyrinthe des couples illégitimes, de l'amour à la haine en passant par la jalousie, le spectre de l'ennui, l'excitation du danger, les délires d'interprétation, et ce doute incessant qui corrode les âmes les mieux armées plus profondément que toute culpabilité.

La Fin d'une liaison est l'un de ses romans dont l'empreinte sur le lecteur est la plus prégnante. C'est le troisième volet d'une manière de trilogie sur la question de la grâce divine. Un homme et une femme, à Londres, pendant la guerre. Elle est mariée à un fonctionnaire civil, il est écrivain et célibataire ; leur rencontre est un coup de foudre. Un jour, alors qu'ils se retrouvent dans une chambre d'hôtel, une bombe allemande leur tombe dessus. Pendant quelques minutes, elle est convaincue qu'il est mort sous les décombres. Lorsqu'il réapparaît, elle met un terme à leur relation, sans explication. Craignant qu'elle ait changé d'amant, il la fait suivre par un détective : en fait, elle se rend régulièrement chez un ecclésiastique... Pour la première fois, Graham Greene usait du « je » dans un roman. À une rupture dans sa vie devait correspondre une rupture dans son style. Il savait qu'on n'est jamais mieux masqué que lorsqu'on écrit à la première personne. L'histoire de cette folle passion amoureuse était la sienne. À sa parution, en 1951, le roman était dédié à une mystérieuse « C. ». Après la mort de l'écrivain, des biographes révéleront qu'elle s'appelait Catherine, qu'elle était l'épouse de lord Walston, haute personnalité travailliste ; elle fut sa maîtresse de 1946 à 1957, mais jamais ils ne se déprirent l'un de l'autre, leur correspondance jusqu'à la toute fin en témoigne. Il ne l'aimait pas : il l'adorait. Quand Catherine disparut, il envoya un message de condoléances à son mari, lequel répondit : « Vous lui avez donné quelque chose, j'ignore quoi, que personne d'autre ne lui avait donné. » Elle-même, dans sa dernière lettre, lui avouait : « Il n'y a jamais eu quelqu'un comme toi dans ma vie. » On s'en doutait, mais on en a la confirmation : sa vie fut son meilleur roman.

Vingt-six romans et un grand nombre de nouvelles, traduits en quarante langues, entre 1926 et 1990. À quoi il convient d'ajouter des milliers d'articles, une correspondance très fournie, le noircissement quotidien de petits carnets et d'agendas Hermès. Graham Greene, dont rien ni personne ne bridait la curiosité, a touché à tous les genres : roman policier (Un Américain bien tranquille), roman de divertissement (Notre agent à La Havane), roman d'espionnage (Le Facteur humain), thriller (Le Ministère de la peur), essai autobiographique (Une sorte de vie, Les Chemins de l'évasion), scénario (Le Troisième Homme), pamphlet (J'accuse), lettre au courrier des lecteurs des grands journaux, une anthologie des plus savoureuses dans le registre de l'understatement (Avec mes sentiments les meilleurs), et jusqu'à l'interprétation de ses rêves (Mon univers secret). On allait faire l'impasse, impardonnable s'agissant d'un écrivain britannique, sur les nouvelles, dont il évoquait le goût comme « une boisson fraîche dans une bouche brûlante ». Le meilleur, et donc le plus troublant et le plus ambigu, y est reflété d'un écrivain qui admirait Dickens et Conrad, avant d'être lui-même admiré par John Le Carré ; c'est peu dire qu'il a inspiré ce dernier, du moins pour le tourment de la trahison.

On est ce qu'on reçoit et ce qu'on transmet à condition de créer son petit quelque chose dans l'intervalle. Graham Greene ne dissimulait pas que l'écriture était pour lui une thérapie. Le remords lui était si naturel qu'il continuait à remettre ses livres sur le métier après publication. D'une édition à l'autre, les corrections se poursuivaient, jusqu'à transformer le texte en palimpseste. Ses archives déposées à l'université d'Austin, Texas, pourraient être considérées comme faisant partie de ses oeuvres complètes tant elles sont riches et édifiantes. Avant de les verser, ou plutôt de les vendre aux Américains, il en conservait certaines chez lui, c'est-à-dire chez sa compagne française, Yvonne Cloetta, à Antibes. Il m'avait notamment montré dans un grand éclat de rire le dossier que le FBI avait constitué sur lui, le fichant tel un dangereux révolutionnaire. Conséquence moins drôle : alors que son nom était régulièrement évoqué dans les années 1950-1960 comme nobélisable, il était systématiquement barré en raison de sa réputation de « crypto-communiste ». Graham Greene aimait la France, qui le lui rendait bien. Les lecteurs faisaient fête à ses traductions et souvent aux films adaptés de ses romans. Une saga qui avait commencé le jour où, ayant reniflé le dernier Greene dans une librairie de Londres à la fin des années 1940, un jeune éditeur marseillais, un certain Robert Laffont, s'était présenté tout simplement au domicile de l'écrivain pour lui dire son désir de le publier en français et de signer un contrat, lequel fut tacitement renouvelé pendant des décennies. À la fin des années 1980, comme le romancier passait par Paris, l'éditeur lui fit la surprise d'organiser une projection privée sur grand écran du chef-d'oeuvre dont il avait été le scénariste : Le Troisième Homme de Carol Reed ; et, pour y avoir assisté assis entre l'un et l'autre, je puis témoigner de l'intensité de l'estime et de l'amitié qui lient parfois un auteur et son éditeur.

Greeneland ! L'intéressé détestait cette AOC qui nimbait son oeuvre. Pourtant, cet univers métaphysique, et même psychologique, se reconnaissait d'emblée. François Gallix, l'un de ses meilleurs connaisseurs, le ramasse ainsi : « Un arrière-plan très typé donnant une fausse impression de réalisme et dont la couleur locale n'est pas totalement absente, tout en étant très imprégné de symbolisme, avec des personnages entre deux âges, esseulés, à bout de course, aux vies souvent ratées - anti-héros solitaires qui sont amenés à faire des choix cruciaux tout en étant capables d'actes de courage. » Encore faut-il préciser qu'un mot clé ouvre la porte de ce monde gris, à la frontière entre le bien et le mal : seediness, que l'on rendrait improprement par « sordidité » ou « sordidisme ».

Pour avoir eu le privilège de passer une journée à bavarder avec lui à bâtons rompus, à l'écouter regretter d'être passé par Moscou sans avoir revu son ami, le traître Kim Philby, dénoncer les clowneries et ragots d'Anthony Burgess à son endroit, démentir qu'Orson Welles ait été l'auteur des dialogues les plus célèbres du Troisième Homme, ce que l'acteur s'attribuait publiquement (« Et pendant ce temps, qu'a inventé la Suisse ? Le coucou ! »), je me souviens notamment d'une phrase : « A novel is never what it is about. » Tout romancier devrait la garder à l'esprit, tout lecteur aussi : un roman, ce n'est pas un sujet, ça parle de tout autre chose que ce qui est annoncé. Bienvenue dans ce territoire de l'imaginaire aux frontières si floues, mais si prégnantes qu'il faut s'en échapper pour savoir qu'on y a été. Un monde où la déloyauté est une vertu, où tout se passe la nuit, où il pleut tout le temps et où celui qui tire les ficelles de l'histoire se fait toujours l'avocat du diable pour les individus hors limites.

Reflections là

những bài viết ngắn, về đủ thứ, những chuyến đi, những bài

điểm sách, điểm phim, giới thiệu sách. Trong có hai

bài thật thú. Một, về những tiệm bán sách cũ,

và một, tưởng niệm Borges, cũng là kỷ niệm lần Greene gặp

Borges. TV sẽ chuyển ngữ cả hai.

Bài về những tiệm sách

cũ làm Gấu nhớ tới những tiệm sách cũ ở khu Chợ Đũi, cũng

một thiên đường tuổi mới lớn của Gấu cùng với Sài

Gòn. Thời gian quen HPA. Gấu đã kể về chúng trong

một bài viết cũ. Đọc bài viết của Greene còn làm

Gấu nhớ tới cái tiệm sách cũ nằm giữa một con hẻm giữa hai

bức tường, của hai căn nhà trên con phố Catinat, cũng gần

Quán Chùa. Gấu thường ghé đó, cùng với

ông Hưng, AP man. Cũng một trong những đền thiêng của VNCH, và

cũng bị VC ủi sập, cùng với Givral, Passage Eden, Quán Chùa.

Tôi không biết Freud

giải thích thế nào về chúng, nhưng trong hơn ba

chục năm, những giấc mơ hạnh phúc nhất của tôi, là

về những tiệm bán sách cũ: những tiệm trước đó tôi

chẳng hề biết, hoàn toàn vô danh đối với tôi,

hay những tiệm quen thuộc, cũ xưa mà tôi đang ghé.

Đó là những tiệm sách quen chẳng hề hiện hữu; tôi thật ngại ngần và đành phải đi đến kết luận như vậy.