Schulz & Walser & Kafka

Bruno Schulz

Bruno Schulz

IN ONE OF his earliest childhood recollections,

young Bruno Schulz sits on the floor ringed by admiring family

members while he scrawls one 'drawing' after another over the pages

of old newspapers. In his creative rapture, the child still inhabits

an 'age of genius', still has unselfconscious access to the realm

of myth. Or so it seemed to the man whom the child became; all

of his mature strivings would be to regain touch with his early powers,

to 'mature into childhood'. These strivings would issue in two bodies of work: etchings and drawings that would probably be of no great interest today had their deviser not become famous by other means; and two short books, collections of stories and sketches about the inner life of a boy in provincial Galicia, which propelled him to the forefront of Polish letters of the interwar years. Rich in fantasy, sensuous in their apprehension of the living world, elegant in style, witty, underpinned by a mystical but coherent idealistic aesthetic, Cinnamon Shops (1934) and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass (1937) were unique and startling productions that seemed to come out of nowhere.

Bruno Schulz was born in 1892, the third child of Jewish parents from the merchant class, and named for the Christian saint on whose name-day his birthday fell. His home town, Drohobycz, was a minor industrial centre in a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that after World War I returned to being part of Poland.

Though there was a Jewish school in Drohobycz, Schulz was sent to the Polish Gymnasium. (Joseph Roth, in nearby Brody, had gone to a German Gymnasium.) His languages were Polish and German; he did not speak the Yiddish of the streets. At school he excelled at art, but was dissuaded by his family from following art as a profession. He registered to study architecture at the polytechnic in Lwow, but in 1914, when war was declared, had to break off his studies. Because of a heart defect he was not called up into the army. Returning to Drohobycz, he set about a programme of intensive self-education, reading and perfecting his draughtsman-ship. He put together a portfolio of graphics on erotic themes entitled The Book of Idolatry and tried to sell copies, with some diffidence and not much success.

Unable to make a living as an artist, saddled, after his father's death, with a houseful of ailing relatives to support, he took a job as an art teacher at a local school, a position he held until 1941.

Though respected by his students, he found school life stultifying and wrote letter after letter imploring the authorities for time off to pursue his creative work, pleas to which, to their credit, they did not always turn a deaf ear.

[suite]

J.M. Coetzee: Inner Workings, essays 2000-2005

Note: Bởi là vì S đã từng dịch Kafka, và giữa họ có cái gì giống nhau, Gấu Cà Chớn bèn nhớ tới Walser. Ông này cũng mắc mớ với Kafka, và cả ba đấng này - có lẽ kể thêm Hoàng Ngọc Tuấn của Cô bé treo mùng - tất cả đám đều bị đời hất hủi, hay nói đúng hơn, đều hất hủi cuộc đời, vào cái dịp SN Tám Bó, Gấu, thay vì tự sướng, thì bèn tưởng niệm những đấng này, thú hơn nhiều.

David Grossman, trong cuốn "Viết Trong Bóng Tối", trong bài viết "Những cuốn sách đọc tôi", cũng dành rất nhiều dòng cho S, ngoài cái bài, được K dịch, từ Người Nữu Ước.

Bèn đi luôn, cùng với bài của Coetzee.

Coetzee cũng có 1 bài về Walser, link sau đây:

http://www.tanvien.net/Tribute_1/Walser_by_Sebald.html

WG Sebald

The Observer

A Place in the Country by WG Sebald – review

Sebald's posthumous essays affirm his ability to make his own obsessions ours too

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/apr/27/wg-sebald-place-country-review

WG Sebald's quietly potent legacy

Out of tune with the hustling digital world, his singular, deeply personal books continue to inspire and intrigue

http://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2013/may/13/wg-sebald-legacy

Note: Trên net có mấy bài về Sebald, link ở đây, rảnh - những khi bớt nhớ ai đó - dịch hầu quí vị độc giả TV, như GCC, mê Sebald, người có tài biến nỗi ám ảnh của ông, thành, của chúng ta

The Observer

A Place in the Country by WG Sebald – review

Sebald's posthumous essays affirm his ability to make his own obsessions ours too

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/apr/27/wg-sebald-place-country-review

WG Sebald's quietly potent legacy

Out of tune with the hustling digital world, his singular, deeply personal books continue to inspire and intrigue

http://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2013/may/13/wg-sebald-legacy

Note: Trên net có mấy bài về Sebald, link ở đây, rảnh - những khi bớt nhớ ai đó - dịch hầu quí vị độc giả TV, như GCC, mê Sebald, người có tài biến nỗi ám ảnh của ông, thành, của chúng ta

EBRUARY 6, 2014

Le Promeneur

Solitaire: W. G. Sebald on Robert Walser

***

A Place in the Country

The Genius of Robert Walser

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2000/nov/02/the-genius-of-robert-walser/

J.M. Coetzee

November 2, 2000 Issue

Was Walser a great writer? If one is reluctant to call him great, said Canetti, that is only because nothing could be more alien to him than greatness. In a late poem Walser wrote:

I would wish it on no one to be me.

Only I am capable of bearing myself.

To know so much, to have seen so much, and

To say nothing, just about nothing.

Walser, nhà văn nhớn?

Nếu có người nào đó, gọi ông ta là nhà văn nhớn, 1 cách ngần ngại, thì đó là vì cái từ “nhớn” rất ư là xa lạ với Walser, như Canetti viết.

Như trong 1 bài thơ muộn của mình, Walser viết:

Tớ đếch muốn thằng chó nào như tớ, hoặc nhớ đến tớ, hoặc lèm bèm về tớ, hoặc mong muốn là tớ

Nhất là khi thằng khốn đó ngồi bên ly cà phê!

Một mình tớ, chỉ độc nhất tớ, chịu khốn khổ vì tớ là đủ rồi

Biết thật nhiều, nhòm đủ thứ, và

Đếch nói gì, về bất cứ cái gì

[Dịch hơi bị THNM. Nhưng quái làm sao, lại nhớ tới lời chúc SN/GCC của K!] (1)

Walser được hiểu như là 1 cái link thiếu, giữa Kleist và Kafka. “Tuy nhiên,” Susan Sontag viết, “Vào lúc Walser viết, thì đúng là Kafka [như được hậu thế hiểu], qua lăng kính của Walser. Musil, 1 đấng ái mộ khác giữa những người đương thời của Walser, lần đầu đọc Kafka, phán, ông này thuổng Walser [một trường hợp đặc dị của Walser]."

Walser được ái mộ sớm sủa bởi những đấng cự phách như là Musil, Hesse, Zweig. Benjamin, và Kafka; đúng ra, Walser, trong đời của mình, được biết nhiều hơn, so với Kafka, hay Benjamin.

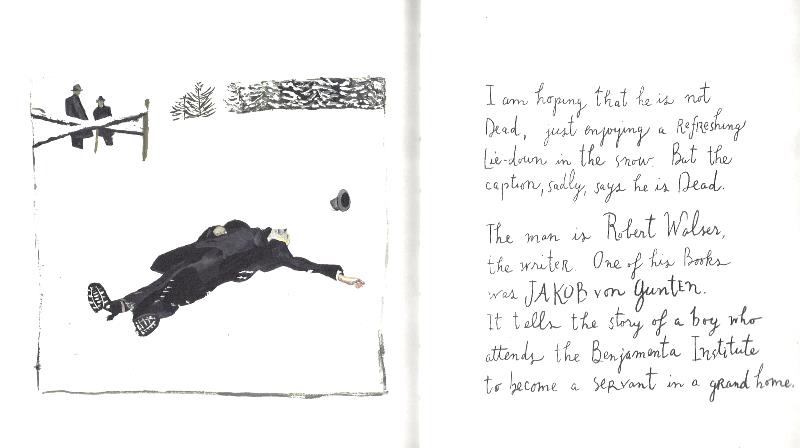

W. G. Sebald, in his essay “Le Promeneur Solitaire,” offers the following biographical information concerning the Swiss writer Robert Walser: “Nowhere was he able to settle, never did he acquire the least thing by way of possessions. He had neither a house, nor any fixed abode, nor a single piece of furniture, and as far as clothes are concerned, at most one good suit and one less so…. He did not, I believe, even own the books that he had written.” Sebald goes on to ask, “How is one to understand an author who was so beset by shadows … who created humorous sketches from pure despair, who almost always wrote the same thing and yet never repeated himself, whose prose has the tendency to dissolve upon reading, so that only a few hours later one can barely remember the ephemeral figures, events and things of which it spoke.”

(1)

To U & O & My home

MY-NESS

"My parents, my husband, my brother, my sister."

I am listening in a cafeteria at breakfast.

The women's voices rustle, fulfill themselves

In a ritual no doubt necessary.

I glance sidelong at their moving lips

And I delight in being here on earth

For one more moment, with them, here on earth,

To celebrate our tiny, tiny my-ness.

To find my home in one sentence, concise, as if hammered in metal.

Not to enchant anybody. Not to earn a lasting name in posterity. An

unnamed need for order, for rhythm, for form, which three words are

opposed to chaos and nothingness.

Berkeley-Paris-Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1981-1983

Czeslaw Milosz: Selected Poems 1931-2004

Note: Thấy trên nét, có bài của Cao Huy Khanh, viết về Nguyễn Mộng Giác, có nhắc tới HNT

https://www.facebook.com/notes/cao-huy-vinh/h%E1%BB%93-s%C6%A1-h%E1%BA%ADu-chi%E1%BA%BFn/588089321580931/

SN_GCC_2017

Oh my August, how could you give me such news

As a terrible anniversary?

Akhmatova: A Dream

(August 14, 1956),

.... vào đúng dịp sinh nhật của chàng, sinh nhật lần thứ ba mươi mà cũng là sinh nhật lần thứ nhất, nàng nói, "Je serai ta femme."

Comments

Post a Comment