Naipaul Tribute

Naipaul's

Book of the World

Hilary

Mantel

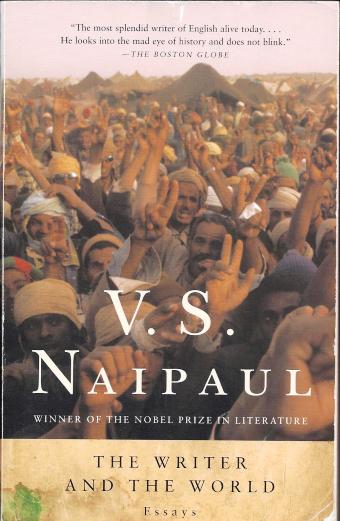

Trong cuốn

"Nhà văn và Thế giới", có bài diễn thuyết của Naipaul, Nền văn minh phổ

cập của

chúng ta, “Our Universal Civilization”, tại Học Viện Manhattan, NY. TV

sẽ giới

thiệu, vì nó liên quan tới vấn nạn khủng bố, và cùng với nó, như 1 đối

trọng, “bịnh

Tây Phương”, a “Western disease”. Ngoài ra TV sẽ giới thiệu bài Naipaul

viết về

cuốn sách thân cận với ông nhất, Ngôi nhà cho me-xừ [A House for Mr.]

Biswas. Bài

này cho Mít chúng ta thấy, có 1 cách viết khác hẳn chúng ta thường

viết, do bị ảnh

hưởng của Tẩy, belles lettres, văn là phải đẹp.

Bài trong sách, dài hơn

nhiều, so với bài trên net, và được ghi là Postscript: Our Universal Civilization.

Đúng hơn, là bài này:

Sir V.S. Naipaul

On October

30, 1990, V S. Naipaul, considered by many to be the greatest living

English

language novelist, delivered the fourth annual Walter B. Wriston

lecture in

Public Policy, sponsored by the Manhattan Institute. Mr. Naipaul takes

as his

subject the “universal civilization” to which the Western values of

tolerance,

individualism, equality, and personal liberty have given birth. He

describes

the personal and philosophical turmoil of those who find themselves

torn

between their native civilizations and the valued of universal

civilization. We

are pleased to present his remarks here in full.

Naipaul Page

Ghi chú về 1 giọng văn: Naipaul

Typical sentence

Easier to pick two of them. What’s most typical is the way one sentence qualifies another. “The country was a tyranny. But in those days not many people minded.” (“A Way in the World”, 1994.)

Câu văn điển hình:

Dễ kiếm hai câu, điển hình nhất, là cái cách mà câu này

nêu phẩm chất câu kia:

"Xứ sở thì là bạo chúa. Nhưng những ngày này, ít ai "ke" chuyện này!"

Naipaul rất tởm cái gọi là quê hương là chùm kế ngọt của ông. Khi được hỏi, giá như mà ông không chạy trốn được quê hương [Trinidad] của mình, thì sao, ông phán, chắc nịch, thì tao tự tử chứ sao nữa! (1)

Tuyệt.

INTERVIEWER

Do you ever wonder what would have become of you if you had stayed in Trinidad?

NAIPAUL

I would have killed myself. A friend of mine did-out of stress, I think. He was a boy of mixed race. A lovely boy, and very bright. It was a great waste.

Sir V.S.

Naipaul (1932- ): Nobel văn chương 2001

“Con người

và nhà văn là một. Đây là phát giác lớn lao nhất của nhà văn. Phải mất

thời

gian – và biết bao là chữ viết! – mới nhập một được như vậy.”

(Man and writer were the same

person. But that

is a writer’s greatest discovery. It took time – and how much writing!

– to arrive

at that synthesis)

V.S. Naipaul, “The Enigma of

Arrival”

Trong bài tiểu luận “Lời

mở đầu cho một Tự thuật”

(“Prologue to an Autobiography”), V.S. Naipaul kể về những di dân Ấn độ

ở

Trinidad. Do muốn thoát ra khỏi vùng Bắc Ấn nghèo xơ nghèo xác của thế

kỷ 19, họ

“đăng ký” làm công nhân xuất khẩu, tới một thuộc địa khác của Anh quốc

là

Trinidad. Rất nhiều người bị quyến rũ bởi những lời hứa hẹn, về một

miếng đất cắm

dùi sau khi hết hợp đồng, hay một chuyến trở về quê hương miễn phí, để

xum họp

với gia đình. Nhưng đã ra đi thì khó mà trở lại. Và Trinidad tràn ngập

những di

dân Ấn, không nhà cửa, không mảy may hy vọng trở về.

Vào năm

1931, con tầu SS Ganges đã đưa một ngàn di dân về Ấn. Năm sau, trở lại

Trinidad, nó chỉ kiếm được một ngàn, trong số hàng ngàn con người không

nhà nói

trên. Ngỡ ngàng hơn, khi con tầu tới cảng Calcutta, bến tầu tràn ngập

những con

người qui cố hương chuyến đầu: họ muốn trở lại Trinidad, bởi vì bất cứ

thứ gì họ

nhìn thấy ở quê nhà, dù một tí một tẹo, đều chứng tỏ một điều: đây

không phải

thực mà là mộng.

Ác mộng.

“Em ra đi

nơi này vẫn thế”. Ngày nay, du khách ghé thăm Bắc Ấn, nơi những di dân

đợt đầu

tiên tới Trinidad để lại sau họ, nó chẳng khác gì ngày xa xưa, nghĩa là

vẫn

nghèo nàn xơ xác, vẫn những con đường đầy bụi, những túp lều tranh vách

đất, lụp

xụp, những đứa trẻ rách rưới, ngoài cánh đồng cũng vẫn cảnh người cày

thay

trâu… Từ vùng đất đó, ông nội của Naipaul đã được mang tới Trinidad,

khi còn là

một đứa bé, vào năm 1880. Tại đây, những di dân người Ấn túm tụm với

nhau, tạo

thành một cộng đồng khốn khó. Vào năm 1906, Seepersad, cha của Naipaul,

và bà mẹ,

sau khi đã hoàn tất thủ tục hồi hương, đúng lúc tính bước chân xuống

tầu, cậu

bé Seepersad bỗng hoảng sợ mất vía, trốn vào một xó cầu tiêu công cộng,

len lén

nhìn ra biển, cho tới khi bà mẹ thay đổi quyết định.

Chính là nỗi đau

nhức trí thức thuộc địa, chính nỗi chết không rời đó, tẩm thấm mãi vào

mình, khiến cho Naipaul có được sự can đảm để làm một điều thật là giản

dị: “Tôi gọi tên em cho đỡ nhớ”.

Em ở đây, là đường phố Port of Spain, thủ phủ Trinidad. Khó khăn, ngại ngùng, và bực bội – dám nhắc đến tên em – mãi sau này, sau sáu năm chẳng có chút kết quả ở Anh Quốc, vẫn đọng ở nơi ông, ngay cả khi Naipaul bắt đầu tìm cách cho mình thoát ra khỏi truyền thống chính quốc Âu Châu, và tìm được can đảm để viết về Port of Spain như ông biết về nó. Phố Miguel (1959), cuốn sách đầu tiên của ông được xuất bản, là từ quãng đời trẻ con của ông ở Port of Spain, nhưng ở trong đó, ông đơn giản và bỏ qua rất nhiều kinh nghiệm. Hồi ức của những nhân vật tới “từ một thời nhức nhối. Nhưng không phải như là tôi đã nhớ. Những hoàn cảnh của gia đình tôi quá hỗn độn; tôi tự nhủ, tốt hơn hết, đừng ngoáy sâu vào đó."

NOTES ON A VOICE: V.S. NAIPAUL

In this third instalment of our series on what makes distinctive writers distinctive, Robert Butler tackles V.S. Naipaul on the eve of his 31st book

From INTELLIGENT LIFE Magazine, Autumn 2010

V.S. Naipaul was born in Trinidad in 1932, when literacy among Indian men on the island stood at 23%. Naipaul’s father had taught himself to read and write and became a journalist for the Trinidad Guardian. He gave his son the idea of the writer’s life and the idea that it was a noble calling. The young Vidia slept on the verandah, where the varied life of Port of Spain, captured in his first book “Miguel Street” (1959), “unrolled every day in front of my eyes”. The conditions that made his literary ambitions so raw and improbable also gave Naipaul his unique perspective. His early exposure to Trinidad’s diverse population—Africans, East Indians, Venezuelans, Chinese, Portuguese, Americans, Syrians and Lebanese—ensured that he wouldn’t sentimentalise other cultures. This gift was immeasurably deepened by his travels in South America, Africa, India, Pakistan, Iran and South-East Asia.

Naipaul attaches equal value to his fiction and

non-fiction and has mastered (as the Nobel committee said) a form of

writing that combines the two. His 31st and latest book, “The Masque of

Africa” (out now in Britain, and in October in America), sees this

tireless observer return, albeit in a slightly more leisurely style

(“we went in his ambassador’s car”), to a continent he first visited 44

years ago.

Golden rule

After university, Naipaul decided the way he had written

undergraduate essays was not “proper writing”. He set himself the task

of learning to write all over again, this time using only simple direct

statements. “Almost writing ‘the cat sat on the mat’. I almost began

like that.” For three years he stayed with those rules. He recently

provided a list of seven rules for beginners at the request of an

Indian newspaper: (1) write sentences of no more than ten to 12 words;

(2) make each sentence a clear statement (a series of clear linked

statements makes a paragraph); (3) use short words—average no more than

five letters; (4) never use a word you don’t know the meaning of; (5)

avoid adjectives except for ones of colour, size and number; (6) use

concrete words, avoid abstract ones; (7) practise these rules every day

for six months.

Key decision

To discard the metropolitan notion of the writer that he

had grown up with—a Somerset Maugham or Evelyn Waugh who moves from a

place of civilised security to investigate the world beyond his own

shores. That kind of “I” was not available to Naipaul. “My subject was

not my sensibility, my inward development, but the worlds I contained

within myself.” (“The Enigma of Arrival”, 1987.)

Strong point

Something he admires in other writers: “Kipling looked

hard at a real town.”

Favourite trick

In his later work, he repeats a phrase from one

paragraph in the next one, which gives his prose an almost biblical

sense of progress. The mythic tone is heightened by short words and

inverted sentences: “In the morning there came the fighter plane.” (“A

Bend in the River”, 1979.) Every evening Naipaul reads out loud what he

has written during the day. Or used to—nowadays he has what he has

written read out to him. This lifelong habit gives his prose the

weightiness of considered thought and the lightness of conversation.

Role models

His father—“possibly the first writer of the Indian

diaspora”—for his short stories about Trinidad’s Indians. Joseph

Conrad, for seriousness and a sense of those living on “the other side

of the fence”. Flaubert, for the “selection and achievement of

detail”. Shakespeare, for freshness of language and the power of his

simplest lines.

Typical sentence

Easier to pick two of them. What’s most typical is the way one sentence qualifies another. “The country was a tyranny. But in those days not many people minded.” (“A Way in the World”, 1994.)

"The Masque of Africa" was published by Picador on August 31st, and by Knopf in America on October 19th

Naipaul: Một nhà văn mất mẹ nó ý thức đạo đức ở trong tác phẩm chẳng là gì dưới mắt tôi, tôi chẳng thèm quan tâm tới thứ nhà văn này. Evelyn Waugh? Tay này có một tham vọng đạo đức? Làm gì có. Nếu có, thì đó là cơ hội. Proust? Bạn đặt trọng tâm đạo đức tác phẩm của ông ta vào chỗ nào? Một thứ kịch xã hội?

Ông thực quá khắt khe với Proust.

Bà vợ, Nadira Naipaul, [tố thêm]:

Còn Gabriel Garcia Marquez? Một thằng cha bất lương, bạn của

lũ bạo chúa. Salman Rushdie hả? Một gã thủ dâm trí

thức.

Vào năm 1967, trong cuốn Lần Viếng Thăm

Thứ Nhì, một thứ phóng sự về Ấn Độ, ông đã

từng nói: "Tất cả những tự thuật Ấn Độ đều được viết bởi, vẫn chỉ

có một người: dở dang". Phải chăng, đây là định nghĩa

Willie? [nhân vật chính trong Nửa Đời Nửa Đoạn, La Moitié d'une vie,

tác phẩm của Naipaul].

Vâng, đúng như vậy. Cám ơn đã để ý

tới điều này.

[Tạp Chí Văn Học Pháp, số Tháng Chín

2005. Naipaul trả lời phỏng vấn]

Ian Buruma

V.S. Naipaul’s fastidiousness was legendary. I met him

for the first time in Berlin, in 1991, when he was feted

for the German edition of his latest book. A smiling young

waitress offered him some decent white wine. Naipaul took

the bottle from her hand, examined the label for some time, like

a fine-art dealer inspecting a dubious piece, handed the bottle

back, and said with considerable disdain: “I think perhaps later,

perhaps later.” (Naipaul often repeated phrases.)

This kind of thing also found its

way into his travel writing. He could work himself up into

a rage about the quality of the towels in his hotel bathroom,

or the slack service on an airline, or the poor food at a restaurant,

as though these were personal affronts to him, the impeccably

turned-out traveler.

Naipaul was nothing if not self-aware.

In his first travel account of India, An Area of Darkness

(1964), he describes a visit to his ancestral village in

a poor, dusty part of Uttar Pradesh, where an old woman clutches

Naipaul’s shiny English shoes. Naipaul feels overwhelmed, alienated,

presumed upon. He wants to leave this remote place his grandfather

left behind many years before. A young man wishes to hitch a ride

to the nearest town. Naipaul says: “No, let the idler walk.” And

so, he adds, “the visit ended, in futility and impatience, a gratuitous

act of cruelty, self-reproach and flight.”

It is tempting to see Naipaul as

a blimpish figure, aping the manners of British bigots;

or as a fussy Brahmin, unwilling to eat from the same plates

as lower castes. Both views miss the mark. Naipaul’s fastidiousness

had more to do with what he called the “raw nerves” of a displaced

colonial, a man born in a provincial outpost of empire, who had

struggled against the indignities of racial prejudice to make

his mark, to be a writer, to add his voice to what he saw as a universal

civilization. Dirty towels, bad service, and the wretchedness

of his ancestral land were insults to his sense of dignity, of having

overcome so much.

These raw nerves did not make him

into an apologist for empire, let alone for the horrors

inflicted by white Europeans. On the contrary, he blamed

the abject state of so many former colonies on imperial conquest.

In The Loss of Eldorado (1969), a short history of his native

Trinidad, he describes in great detail how waves of bloody conquest

wiped out entire peoples and their cultures, leaving half-baked,

dispossessed, rootless societies. Such societies have lost what

Naipaul calls their “wholeness” and are prone to revolutionary

fantasies and religious fanaticism.

Wholeness was an important idea

to Naipaul. To him, it represented cultural memory, a settled

sense of place and identity. History was important to him,

as well as literary achievement upon which new generations of writers

could build. It irked him that there was nothing for him to build

on in Trinidad, apart from some vaguely recalled Brahmin rituals and

books about a faraway European country where it rained all the time,

a place he could only imagine. England, to him, represented a culture

that was whole. And, from the distance of his childhood, so did India.

(In fact, he knew more about ancient Rome, taught by a Latin teacher

in Trinidad, than he did about either country.)

When he finally managed to go to

India, he was disappointed. India was a “wounded civilization,”

maimed by Muslim conquests and European colonialism. He realized

he didn’t belong there, any more than in Trinidad or in England.

And so he sought to find his place in the world through words.

Books would be his escape from feeling rootless and superfluous.

His father, Seepersad Naipaul, had tried to lift himself from his

surroundings by writing journalism and short stories, which he hoped,

in vain, to publish in England. Writing, to father and son, was

more than a profession; it was a calling that conferred a kind of nobility.

Naipaul’s most famous novel, A

House for Mr. Biswas (1961), drew on the father’s story

of frustrated ambition. By going back into the world of his

childhood, he found the words to create his own link to that

universal literary civilization. He often told interviewers

that he only existed in his books.

If raw nerves made him irascible

at times, they also sharpened his vision. He understood

people who were culturally dislocated and who tried to find

solace in religious or political fantasies that were often borrowed

from other places and ineptly mimicked. He described such delusions

precisely and often comically. His sense of humor sometimes bordered

on cruelty, and in interviews with liberal journalists it could

take the form of calculated provocation. But his refusal to sentimentalize

the wounds in postcolonial societies produced some of his most

penetrating insights.

My favorite book by Naipaul is

not A House for Mr. Biswas, or the later novel A Bend

in the River (1979), his various books on India, or even

his 1987 masterpiece The Enigma of Arrival, but a slender

volume entitled Finding the Center (1984). It consists of

two long essays, one about how he learned to become a writer,

how he found his own voice, and the other about a trip to Ivory

Coast in 1982. In the first piece, written out of unflinching self-knowledge,

he gives a lucid account of the way he sees the world, and how he

puts this in words. He travels to understand himself, as well as

the politics and histories of the countries he visits. Following

random encounters with people who interest him, he tries to understand

how people see themselves in relation to the world they live in. But

by doing so, he finds his own place, too, in his own inimitable words.

The second part of Finding the

Center, called “The Crocodiles of Yamassoukro,” is a perfect

example of his methods. It is a surprisingly sympathetic account

of a messed-up African country, filled with foreigners as

well as local people wrapped up in a variety of self-told stories,

some of them fantastical, about how they see themselves fitting

in. African Americans come in search of an imaginary Africa. A

black woman from Martinique escapes in a private world of quasi-French

snobbery. And the Africans themselves, in Naipaul’s vision, have

held onto a “whole” culture under a thin layer of false mimicry.

This culture of ancestral spirits comes alive at night, when the

gimcrack modernity of daily urban life is forgotten.

Being in Africa reminds him of

his childhood in Trinidad, when descendants of slaves

turned the world upside down in carnivals, in which the oppressive

white world ceased to exist and they reigned as African kings

and queens. It is an oddly romantic vision of African life, this

idea that something whole lurks under the surface of a half-made,

borrowed civilization. Perhaps it is more telling of Naipaul’s

own longings than of the reality of most people’s lives. If he is

always clear-eyed about the pretentions of religious fanatics, Third

World mimic men, and delusional political figures, his idea of wholeness

can sound almost sentimental.

I remember being in a car with

Naipaul one summer day in Wiltshire, England, near the

cottage where he lived. He told me about his driver, a local

man. The driver, he said, had a special bond with the rolling

hills we were passing through. The man was aware of his ancestors

buried under our feet. He belonged here. He felt the link with

generations that had been here before him: “That is how he thinks,

that is how he thinks.”

I am not convinced at all that

this was the way Naipaul’s driver thought. But it was

certainly the way he thought in the writer’s imagination. Naipaul

was our greatest poet of the half-baked and the displaced. It

was the imaginary wholeness of civilizations that sometimes led

him astray. He became too sympathetic to the Hindu nationalism

that is now poisoning India politics, as if a whole Hindu civilization

were on the rise after centuries of alien Muslim or Western despoliations.

There is no such thing as a whole

civilization. But some of Naipaul’s greatest literature

came out of his yearning for it. Although he may, at times,

have associated this with England or India, his imaginary civilization

was not tied to any nation. It was a literary idea, secular,

enlightened, passed on through writing. That is where he made

his home, and that is where, in his books, he will live on.

August 13, 2018, 1:39 pm

Cái chuyện “cà chớn, phách lối, mất

dậy…”, [fastidiousness: chảnh] của GCC - ấy chết xin lỗi, của Naipaul

- thì đúng là cả 1 giai thoại. Tôi lần đầu

gặp ông ta ở Berlin, khi nhà xb tổ chức lễ ra mắt, bản tiếng

Đức, cuốn tiểu thuyết mới nhất của ông. Một em đẹp như tiên,

nụ cười rạng rỡ, mời ông ly rượu vang trắng, chắc không phải

thứ tệ, Naipaul gỡ cái chai ra khỏi tay người đẹp, nhìn cái

nhãn bằng 1 con mắt nghi ngờ của 1 tay nhà nghề trong việc

kiểm tra thật-giả trong văn chương, nghệ thuật, rồi, trả lại chai rượu,

và nói, với 1 cái giọng dè bỉu thật rõ

nét, “lát nữa, lát nữa, em nhá… “, ông

có tật cắn phải lưỡi của mình, không phải một, nhưng

mà là, vài lần!

Trên Tin Văn, còn bài "Duyên nợ văn chương", cũng thật tuyệt.

Trân trọng khoe hàng!

Pankaj Mishra giới thiệu tập tiểu luận Literary Occasions [nhà xb Vintage Canada, 2003], của V.S. Naipaul.

Ông nói, " Đạo đức là cấu trúc.

Quá tuyệt.

Brodsky, Mỹ là Mẹ của Đạo Hạnh, là cùng/cũng nghĩa như thế.

Nhưng phải Kafka, thì mới đẩy đến tận cùng của cái gọi là “kỹ thuật viết”: Linh hồn của văn chương.

Bản thân Naipaul cũng bắt đầu bằng những cái bên ngoài của những sự vật, hy vọng từ đó tới được, qua văn chương, “một thế giới đầy đủ đợi chờ tôi ở đâu đó”. “Tôi giả dụ”, Naipaul viết, trong một tiểu luận về Conrad được xuất bản vào năm 1974, “bằng sự quái dị của mình, tôi nhìn ra, chính tôi, đến Anh Quốc, như tới một miền đất chỉ thuần có ở trong cõi văn chương, ở đó, chẳng bị trắc trở, khó khăn vì biến cố, tai nạn lịch sử hay gốc gác, nền tảng, tôi làm ra một sự nghiệp văn chương, như là một nhà văn chính hiệu con nai vàng.” Nhưng hỡi ơi, thay vì vậy, một sự khiếp đảm chính trị [a political panic] tóm lấy ông, ngay vừa mới ló đầu ra khỏi cái thế giới tù đọng của vùng đất thuộc địa Trinidad. Dời đổi tới một thế giới lớn hơn, theo Naipaul, nghĩa là, ngộ ra rằng, có một lịch sử của đế quốc, và cái lịch sử này thì thật là độc địa, tàn nhẫn, và cùng lúc, thấm thía chỗ của mình, ở trong đó; trần truồng ra trước những xã hội nửa đời nửa đoạn, tức chỉ có một nửa, [half-made societies], tức những xã hội thuộc điạ: chúng cứ thường xuyên tự nhồi nặn lẫn nhau [“constantly made and unmade themselves”]: những phát giác đau thương như thế đó, thay vì dần dần lắng dịu đi, chúng lại càng trở nên nhức nhối hơn, khi ông dám chọn cho mình một ‘nghiệp văn”, ở Anh Quốc.

Hầu như trơ cu lơ, đơn độc, giữa tất cả những nhà văn lớn viết bằng tiếng Anh, nhưng Conrad, chính ông ta có vẻ như đã giúp đỡ, và hiểu Naipaul và hoàn cảnh trớ trêu của ông, một tay lưu vong tới từ một vùng đất thuộc địa, và thấy mình đang loay hoay, kèn cựa, cố tìm cho bằng được cái chỗ đứng, như là một nhà văn, ở trong một đế quốc [thấy mình làm việc trong một thế giới và truyền thống văn học được nhào nặn bởi đế quốc … “who finds himself working in a world and literay tradition shaped by empire”]. Conrad là “nhà văn hiện đại đầu tiên” mà Naipaul đã được ông via của mình giới thiệu. Thoạt đầu, ông này làm Naipaul bị khớp, bởi “những câu chuyện bản thân chúng thật là giản dị, và luôn luôn, tới một giai đoạn nào đó, chúng trượt ra khỏi tôi”. Sau đó, Naipaul giản dị hoá vấn đề, bằng cách, khoán trắng cho những sự kiện. Đọc Trái Tim Của Bóng Đen, ông coi, nó là như vậy đấy: nền tảng của cuốn tiểu thuyết là Phi Châu - một vùng đất bại hoại bởi sự cướp bóc, bóc lột, và bởi sự độc ác “có môn bài” [licensed cruelty].

Du lịch và viết, đối với Naipaul, là một cách để bầy ra sự ngây thơ chính trị này, của người thuộc địa. Theo Naipaul, giá trị của Conrad – cũng là một kẻ lạ, một kẻ ở bên ngoài nước Anh, và một nhà du lịch kinh nghiệm đầy mình, ở Á Châu và Phi Châu - nằm ở trong sự kiện là, “ngó bất cứ chỗ nào, thì ông ta cũng đã ở đó, trước tôi.”, “ông ta như đã đi guốc vào trong bụng tôi, theo nghĩa, ông là một trạm chung chuyển, “một kẻ trung gian, về thế giới của tôi”, về “những nơi chốn tối tăm, xa vời”, ở đó, những con người, “bị chối từ, vì bất cứ một lý do nào, một cái nhìn thật rõ ràng về thế giới”.

Naipaul coi tác phẩm của Conrad, là đã “thâm nhập vào rất nhiều góc thế giới, mà ông ta thấy, đen thui ở đó.” Naipaul coi đây là một sự kiện mà ông gọi là “một đề tài suy tư theo kiểu Conrad”; “nó nói cho chúng ta một điều”, Naipaul viết, “về thế giới mới của chúng ta”. Chưa từng có một nhà văn nào suy tư về những trò tiếu lâm, tức cười, trớ trêu này, của lịch sử, suy tư dai như đỉa đói, như là Naipaul, nhưng sự sống động ở nơi ông, có vẻ như đối nghịch với vẻ trầm tĩnh [calm] của Conrad, và cùng với vẻ trầm tĩnh của ông nhà văn Hồng Mao này, là nỗi buồn nhẹ nhàng của một kẻ tự mãn, tự lấy làm hài lòng về chính mình. Có vẻ như Naipaul cố làm sáng mãi ra, và đào sâu thêm mãi, tri thức và kinh nghiệm, hai món này, đối với Conrad, ông coi như đã hoàn tất đầy đủ, và cứng như đinh đóng cột. Bó trọn gói, những cuốn sách của Naipaul không chỉ miêu tả nhưng mà còn khuấy động, và cho thấy, bằng cách nào, khởi từ “những nơi chốn tối tăm và xa xôi” của Conrad”, ông dần dà mò về phiá, ở đó, có một cái nhìn thật là rõ ràng về thế giới [a clear vision of the world]. Chẳng có điểm nghỉ ngơi, trong chuyến đi này, mà bây giờ, cuộc đi này, tức cuời thay, có vẻ như là một hành trình lật ngược chuyến đi tới trái tim của bóng đen, của Conrad. Mỗi cuốn sách, là một bắt đầu mới, nó tháo bung những gì trước nó. Điều này giải thích bi kịch không bao giờ chấm dứt, và cứ thế lập đi lập lại mãi, của Sự Tới [arrival], nó có vẻ như là một ám ảnh khởi nghiệp văn, ở trong những tác phẩm của Naipaul.

"Có đến một nửa những tác phẩm của một nhà văn, là chỉ để loay hoay khám phá đề tài”, Naipaul viết, trong “Lời Mở cho một Tự Thuật”. Nhưng văn nghiệp của chính ông cho thấy, một sự khám phá ra như thế có thể chiếm cứ hầu như trọn cuộc đời của một nhà văn, và cũng còn tạo nên, cùng lúc, tác phẩm của người đó - đặc biệt đối với một nhà văn theo kiểu Naipaul: một nhà văn bán xới, vừa độc nhất, vừa đa đoan rắc rối làm sao [a writer as uniquely and diversely displayed as Naipaul], một nhà văn mà, không như những nhà văn Nga xô thế kỷ 19, chẳng hề có một truyền thống văn học phát triển nào, mà cũng chẳng có một xứ sở rộng lớn đa đoan phức tạp nào, để mà “trông cậy vào đó, và đòi hỏi”.

Để nhận ra những sắc thái gẫy vụn, rã rời của căn cước của bạn; để nhìn ra, bằng cách nào những mảnh vụn đó làm cho bạn trở thành là bạn; để hiểu rõ, điều gì cần thiết ở cái quá khứ đau đớn, và khó chịu và chấp nhận nó, như là một phần của hiện hữu của bạn - một hiện hữu như là một tiến trình không ngừng nghỉ, một tiến trình, thực sự mà nói, của hồi tưởng, của tái cấu tạo một cái tôi cá thể nằm dưới sâu trong căn nhà lịch sử của nó, đó là điều phần lớn tác phẩm của Naipaul say mê dấn mãi vào. Người kể chuyện của nhà văn Pháp Proust, ở trong Đi Tìm Một Thời Gian Đã Mất, định nghĩa, cũng một sợi dây nối kết sống động như vậy, giữa hồi nhớ, tri-thức-về-mình, và nỗ lực văn chương, khi anh ta nói, sáng tạo ra một nghệ phẩm cũng đồng nghĩa với khám phá ra cuộc đời thực của chúng ta, cái tôi thực của chúng ta, và, “chúng ta chẳng tự do một tí nào, theo nghĩa, chúng ta không chọn lựa, bằng cách nào, chúng ta sẽ làm đời mình, bởi vì nó có từ trước, và do đó, chúng ta bị bắt buộc phải làm ra đời mình. Và, đời của mình thì vừa cần thiếu, vừa trốn biệt đâu đâu, và, nếu làm ra đời mình là luật sinh tồn của thiên nhiên, nếu như vậy, làm đời mình, có nghĩa là, khám phá ra nó.”

Note:

Cái thế giới 1 nửa, mà cái thiếu nhất của nó, là đạo hạnh, mà đạo hạnh, là cấu trúc, 1 trong cái xứ như thế, là xứ Mít, của chúng ta, trong nó, khủng hơn hết, là cái phần Bắc Kít của nó, đúng là như thế đó. Cái gọi là 4 ngàn năm văn hiến, được gọi thẳng thừng ra ở đây, là, chưa từng biết đến thế nào là dân chủ, thế nào là quyền con người, sợ còn chẳng biết thế nào là tính người, tình người!

Đâu chỉ 1 Naipaul.

Rushdie cũng nhận ra điều này:

Ở Mỹ Châu La Tinh, thực tại biến dạng do chính trị nhiều hơn là do văn hóa. Sự thực được bưng bít đến nỗi không còn biết đâu là sự thực. Cuối cùng chỉ còn một sự thực độc nhất, đó là lúc nào người ta cũng nói dối. Những tác phẩm của Garcia Marquez không có tương quan trực tiếp tới chính trị, nhưng chúng đề cập tới những vấn đề đại chúng bằng những ẩn dụ. Chủ nghĩa hiện thực huyền ảo là một khai triển chiết ra từ chủ nghĩa siêu thực; một chủ nghĩa siêu thực diễn tả lương tâm đích thực của Thế Giới Thứ Ba, tức là của những xã hội được tạo thành "có một nửa", trong đó, cái cũ có vẻ như không thực chống lại cái mới làm người ta sợ, trong đó sự tham nhũng, thối nát "công cộng" của đám cầm quyền và nỗi khiếp sợ "riêng tư" của từng người dân, tất cả đều trở thành hiển nhiên. Trong thế giới tiểu thuyết của Garcia Marquez, những điều vô lý, những chuyện không thể xẩy ra, đều xẩy ra hoài hoài, ngay giữa ban ngày ban mặt. Thật hết sức lầm lẫn, nếu coi vũ trụ văn chương của ông là một hệ thống bịa đặt, khép kín. Nó không được viết ở trên mảnh đất nào khác mà chính là mảnh đất chúng ta đang sống. Macondo có thực. Và đó tính nhiệm mầu của ông.

Tình yêu và những quỷ dữ khác

Lẽ tất nhiên, phán như thế thí quá là quá đáng. Người phán tuyệt nhất về xứ Bắc Kít, với GCC, là Milosz, khi ông vinh danh quê hương của ông, và cùng với ông, là Coetzee, khi định nghĩa thế nào là cổ điển.

Theo nghĩa đó, Kis đọc Nabokov, và gọi đó là lòng hoài nhớ. Đọc bài của ông, thì Gấu thấy mình bớt khe khắt với Nabokov, và thứ văn chương gọi là hoài cổ, đúng thứ văn chương mà LMH [Lê Minh Hà] đang viết về 1 miền đất, trước khi bị VC xóa sổ.

Danilo Kis

When Kis died in Paris in 1989, the Belgrade press went

into national mourning. The renegade star of Yugoslav literature had been

extinguished. Safely dead, he could be eulogized by the mediocrities who

had always envied him and had engineered his literary excommunication,

and who would then proceed-as Yugoslavia fell apart-to become official

writers of the new post- Communist, national chauvinist order. Kis is,

of course, admired by everyone who genuinely cares about literature, in

Belgrade as elsewhere. The place in the former Yugoslavia where he was and

is perhaps most ardently admired is Sarajevo. Literary people there did

not exactly ply me with questions about American literature when I went

to Sarajevo for the first time in April 1993. But they were extremely impressed

that I'd had the privilege of being a friend of Danilo Kis. In besieged

Sarajevo people think a lot about Danilo Kis. His fervent screed against

nationalism, incorporated into The Anatomy Lesson, is one of the two prophetic

texts-the other is a story by Andric, "A Letter from 1920"-that one hears

most often cited. As secular, multi-ethnic Bosnia-Yugoslavia's Yugoslavia-is

crushed under the new imperative of one ethnicity lone state, Kis is more

present than ever. He deserves to be a hero in Sarajevo, whose struggle

to survive embodies the honor of Europe.

Unfortunately, the honor of Europe has been lost at Sarajevo.

Kis and like-minded writers who spoke up against nationalism and fomented-from-the-top

ethnic hatreds could not save Europe's honor, Europe's better idea. But

it is not true that, to paraphrase Auden, a great writer does not make anything

happen. At the end of the century, which is the end of many things, literature,

too, is besieged. The work of Danilo Kis preserves the honor of literature.

Susan Sontag

Khi Kis mất ở Paris năm 1989, báo chí Belgrade

bèn đi 1 đường tưởng niệm tầm cỡ quốc gia: Ngôi sao văn học

đỉnh cao, thoái hóa, đồi trụy Ngụy nghiệc cái con

mẹ gì đó… đã tắt lịm! Đám nhà văn thuộc

Hội Nhà Thổ suốt đời thèm viết được, chỉ 1 câu văn của

ông, bèn thổi ông tới trời, và biến ông,

vốn nhà văn Ngụy, thành nhà văn của nhà nước

VC hậu 30 Tháng Tư 1975!

Lẽ tất nhhiên Kis được yêu mến bởi bất cứ 1 ai thực sự

yêu văn chương và “care” về nó, ở Belgrade hay bất cứ

nơi nào. Nơi chốn thuộc Cựu Nam Tư mà ông được yêu

mến nhất là Sarajevo. Khi tôi [Susan Sontag] tới đó

vào Tháng Tư 1993, đám nhà văn ở đó

bị ấn tượng nặng khi biết tôi hân hạnh được là bạn

của Kis.

Various critics have seen a relationship between your novels and those of Hermann Broch, Bruno Schulz, and Kafka. Do you think there is a Central European tradition-and, if so, how would you describe it?

I have nothing against the notion of Central Europe - on the contrary, I think that I am a Central European writer, according to my origins, especially my literary origins. It's very hard to define what being Central European means, but in my case there were three components. There's the fact that I'm half-Jewish, or Jewish, if you prefer; that I lived in both Hungary and Yugoslavia and that, growing up, I read in two languages and literatures; and that I encountered Western, Russian, and Jewish literature in this central area between Budapest, Vienna, Zagreb, Belgrade, etc. In terms of my education, I'm from this territory. If there's a different style and sensibility that sets me apart from Serbian or Yugoslav literature, one might call it this Central European complex. I find that I am a Central European writer to the core, but it's hard to define, beyond what I've said, what that means to me and where it comes from.

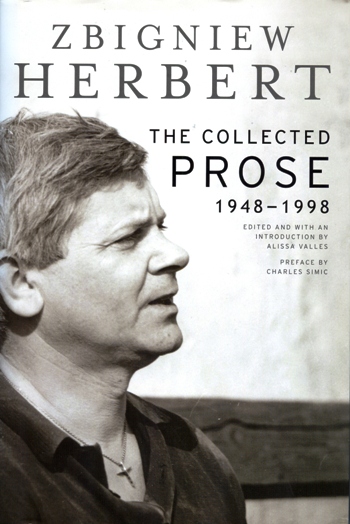

Note: GCC biết đến cái tên của me-xừ Herbert qua bài viết của Coetzee, Thế nào là cổ điển ? Cũng tính đọc, vì nghĩ Mít rất cần (1), nhưng lại nhớ đến cái "deal" với me-xừ Thượng Đế, giống như anh chàng trong truyện ngắn Phép Lạ Bí Ẩn của Borges, mi chỉ được ta cho phép tới năm 70, là lên tầu suốt đấy nhé!

Bữa nay, thì lại nhớ đến

cái tay triết gia bị tử hình, vào giờ chót còn

xin học 1 điệu nhạc… sến!

Thế là đành tặc lưỡi bệ cuốn sách vừa dày,

vừa nặng ký, vừa nặng tiền về nhà mình!

Còn số báo thì lại rẻ quá. Spring

2012, như vậy là ba tháng mới ra 1 kỳ, vậy mà giá

thua 1 số The New Yorker, ra hàng tuần.

Có hai bài phỏng vấn, đọc sơ sơ thấy được quá!

(1)

Với Herbert, đối

nghịch Cổ Điển không phải Lãng Mạn, mà là Man

Rợ. Với nhà thơ Ba Lan, viết từ mảnh đất văn hóa Tây

Phương không ngừng quần thảo với những láng giềng man rợ, không

phải cứ có được một vài tính cách quí

báu nào đó, là làm cho cổ điển sống sót

man rợ.

Nhưng đúng hơn là như thế này: Cái sống

sót những xấu xa tồi tệ nhất của chủ nghĩa man rợ, và cứ thế

sống sót, đời này qua đời khác, bởi những con người

nhất quyết không chịu buông xuôi, nhất quyết bám

chặt lấy, với bất cứ mọi tổn thất, (at all costs), cái mà con

người quyết giữ đó, được gọi là Cổ Điển

(2)

Bạn phải đọc thêm câu

này, của Milosz, thì mới thấm ý, và cùng

gật gù thông cảm với thằng cu Gấu nhà quê, Bắc

Kít:

It is good to be

born in a small country where nature is on a human scale, where various

languages and religions have coexisted for centuries. I am thinking here

of Lithuania, a land of myth and poetry.

Thật lốt lành khi sinh ra tại một xứ nhỏ, nơi thiên nhiên

không so le với con người, nơi ngôn ngữ và tôn

giáo cùng rong ruổi bên nhau qua nhiều đời. Tôi

đang nghĩ về Lithuania, miền đất của huyền thoại và thi ca.

Czeslaw Milosz, Diễn văn Nobel văn chương.

(2)

What does it mean in living terms

to say that the classic is what survives? How does such a conception of the

classic manifest itself in people's lives?

For the most serious answer to this question, we cannot do better than

turn to the great poet of the classic of our own times, the Pole Zbigniew

Herbert. To Herbert, the opposite of the classic is not the Romantic but

the barbarian; furthermore, classic versus barbarian is not so much an

opposition as a confrontation. Herbert writes from the historical perspective

of Poland, a country with an embattled Western culture caught between intermittently

barbarous neighbors. It is not the possession of some essential quality

that, in Herbert's eyes, makes it possible for the classic to withstand

the assault of barbarism. Rather, what survives the worst of barbarism,

surviving because generations of people cannot afford to let go of it and

therefore hold on to it at all costs-that is the classic.

Coetzee: What is a classic ?

[Thế nào là 1 nhà cổ điển ?]

Không phải tự nhiên

mà Coetzee phong cho Herbert là nhà cổ điển vĩ đại

nhất của thời đại chúng ta.

Trong bài giới thiệu Herbert, Charles Simic cho biết, thơ rất ư đầu đời của Herbert lèm bèm về cổ điển:

From the very beginning, Herbert's poems had one notable quality; many of them dealt with Greek and Roman antiquity. These were not the reverential versions of ancient myths and historical events one normally encounters in poetry in which the poet neither questions the philosophical nor the ethical premises of the classical models, but were ironic reevaluations from the point of view of someone who had experienced modern wars and revolutions and who knew well that true to Homeric tradition only the high and mighty are usually glorified and lamented in their death and never the mounds of their anonymous victims. What drew him to the classics, nevertheless, is the recognition that these tales and legends contain all the essential human experiences. To have a historical consciousness meant seeing the continuity of the past as well as recognizing the continuity and the inescapable presence of past errors, crimes, but also the examples of courage and wisdom in our contemporary lives. History is the balance sheet of conscience. It condemns, reminds, robs us of peace, and also enlightens us now and then. In his view, our predicament has always been both tragic and comic. Even the old gods ended just like us.

Even the old gods ended just like us.

Ngay cả những vị thần cổ xưa chấm dứt đúng như chúng ta.

Tuyệt.

Nhìn như thế, thì hoài cổ có nghĩa là, chết như những vị thần cổ xưa của 1 miền đất.

Milosz đã diễn tả tâm trạng này, qua tình cảnh 1 gia đình, ở 1 sân ga, từ đâu chuyển về Lò Thiêu.

Chỉ 1 dúm người trong 1 gia đình, cố túm tụm lại, trước khi bị hủy diệt, trước hỗn loạn.

Bà cụ Gấu, trước khi vô Nam, cố gặp lại bà chị Gấu, nữ anh hùng thồ hàng chiến dịch Điện Biên Phủ. Bà cụ nói với con gái, thà chết 1 đống còn hơn sống 1 người. Bà chị Gấu lắc đầu, vì còn mê “phong trào”.

Lần Gấu trở lại đất Bắc, bà chị than, đúng ra là phải đi theo mẹ!

Gấu sợ rằng xứ Bắc Kít, và cùng với nó, cả nước Mít, đang ở vào bước ngoặt vĩ đại, trước khi thở hắt ra 1 phát, rồi… đi!

Tuyet Nguyen to Quoc Tru Nguyen

CHÚC NHÀ THƠ MẠNH GIỎI,THỎA CHÍ BÌNH SINH ĐẾN TRĂM TUỔI .

NQT

https://www.nybooks.com/…/v-s-naipaul-poet-of-the-displaced/

Ian Buruma

V.S. Naipaul’s fastidiousness was legendary. I met him

for the first time in Berlin, in 1991, when he was feted for

the German edition of his latest book. A smiling young waitress

offered him some decent white wine. Naipaul took the bottle

from her hand, examined the label for some time, like a fine-art

dealer inspecting a dubious piece, handed the bottle back, and said

with considerable disdain: “I think perhaps later, perhaps later.”

(Naipaul often repeated phrases.)

This kind of thing also found its way into

his travel writing. He could work himself up into a rage about

the quality of the towels in his hotel bathroom, or the slack

service on an airline, or the poor food at a restaurant, as though

these were personal affronts to him, the impeccably turned-out

traveler.

Naipaul was nothing if not self-aware.

In his first travel account of India, An Area of Darkness

(1964), he describes a visit to his ancestral village in a

poor, dusty part of Uttar Pradesh, where an old woman clutches

Naipaul’s shiny English shoes. Naipaul feels overwhelmed, alienated,

presumed upon. He wants to leave this remote place his grandfather

left behind many years before. A young man wishes to hitch a ride

to the nearest town. Naipaul says: “No, let the idler walk.” And

so, he adds, “the visit ended, in futility and impatience, a gratuitous

act of cruelty, self-reproach and flight.”

It is tempting to see Naipaul as a blimpish

figure, aping the manners of British bigots; or as a fussy

Brahmin, unwilling to eat from the same plates as lower castes.

Both views miss the mark. Naipaul’s fastidiousness had more to

do with what he called the “raw nerves” of a displaced colonial,

a man born in a provincial outpost of empire, who had struggled against

the indignities of racial prejudice to make his mark, to be a writer,

to add his voice to what he saw as a universal civilization. Dirty

towels, bad service, and the wretchedness of his ancestral land were

insults to his sense of dignity, of having overcome so much.

These raw nerves did not make him into

an apologist for empire, let alone for the horrors inflicted

by white Europeans. On the contrary, he blamed the abject state

of so many former colonies on imperial conquest. In The Loss

of Eldorado (1969), a short history of his native Trinidad, he

describes in great detail how waves of bloody conquest wiped out entire

peoples and their cultures, leaving half-baked, dispossessed, rootless

societies. Such societies have lost what Naipaul calls their “wholeness”

and are prone to revolutionary fantasies and religious fanaticism.

Wholeness was an important idea to Naipaul.

To him, it represented cultural memory, a settled sense of

place and identity. History was important to him, as well as literary

achievement upon which new generations of writers could build.

It irked him that there was nothing for him to build on in Trinidad,

apart from some vaguely recalled Brahmin rituals and books about a

faraway European country where it rained all the time, a place he could

only imagine. England, to him, represented a culture that was whole.

And, from the distance of his childhood, so did India. (In fact, he

knew more about ancient Rome, taught by a Latin teacher in Trinidad,

than he did about either country.)

When he finally managed to go to India,

he was disappointed. India was a “wounded civilization,” maimed

by Muslim conquests and European colonialism. He realized he

didn’t belong there, any more than in Trinidad or in England.

And so he sought to find his place in the world through words. Books

would be his escape from feeling rootless and superfluous. His father,

Seepersad Naipaul, had tried to lift himself from his surroundings

by writing journalism and short stories, which he hoped, in vain,

to publish in England. Writing, to father and son, was more than a

profession; it was a calling that conferred a kind of nobility.

Naipaul’s most famous novel, A House for

Mr. Biswas (1961), drew on the father’s story of frustrated

ambition. By going back into the world of his childhood, he found

the words to create his own link to that universal literary civilization.

He often told interviewers that he only existed in his books.

If raw nerves made him irascible at times,

they also sharpened his vision. He understood people who

were culturally dislocated and who tried to find solace in

religious or political fantasies that were often borrowed from

other places and ineptly mimicked. He described such delusions precisely

and often comically. His sense of humor sometimes bordered on cruelty,

and in interviews with liberal journalists it could take the form

of calculated provocation. But his refusal to sentimentalize the

wounds in postcolonial societies produced some of his most penetrating

insights.

My favorite book by Naipaul is not A House

for Mr. Biswas, or the later novel A Bend in the River (1979),

his various books on India, or even his 1987 masterpiece The

Enigma of Arrival, but a slender volume entitled Finding the

Center (1984). It consists of two long essays, one about how he

learned to become a writer, how he found his own voice, and the

other about a trip to Ivory Coast in 1982. In the first piece, written

out of unflinching self-knowledge, he gives a lucid account of the

way he sees the world, and how he puts this in words. He travels to

understand himself, as well as the politics and histories of the countries

he visits. Following random encounters with people who interest him,

he tries to understand how people see themselves in relation to the

world they live in. But by doing so, he finds his own place, too, in his

own inimitable words.

The second part of Finding the Center,

called “The Crocodiles of Yamassoukro,” is a perfect example

of his methods. It is a surprisingly sympathetic account of

a messed-up African country, filled with foreigners as well as

local people wrapped up in a variety of self-told stories, some

of them fantastical, about how they see themselves fitting in. African

Americans come in search of an imaginary Africa. A black woman from

Martinique escapes in a private world of quasi-French snobbery.

And the Africans themselves, in Naipaul’s vision, have held onto

a “whole” culture under a thin layer of false mimicry. This culture

of ancestral spirits comes alive at night, when the gimcrack modernity

of daily urban life is forgotten.

Being in Africa reminds him of his childhood

in Trinidad, when descendants of slaves turned the world

upside down in carnivals, in which the oppressive white world

ceased to exist and they reigned as African kings and queens.

It is an oddly romantic vision of African life, this idea that something

whole lurks under the surface of a half-made, borrowed civilization.

Perhaps it is more telling of Naipaul’s own longings than of the

reality of most people’s lives. If he is always clear-eyed about the

pretentions of religious fanatics, Third World mimic men, and delusional

political figures, his idea of wholeness can sound almost sentimental.

I remember being in a car with Naipaul

one summer day in Wiltshire, England, near the cottage where

he lived. He told me about his driver, a local man. The driver,

he said, had a special bond with the rolling hills we were passing

through. The man was aware of his ancestors buried under our feet.

He belonged here. He felt the link with generations that had been here

before him: “That is how he thinks, that is how he thinks.”

I am not convinced at all that this was

the way Naipaul’s driver thought. But it was certainly the

way he thought in the writer’s imagination. Naipaul was our

greatest poet of the half-baked and the displaced. It was the imaginary

wholeness of civilizations that sometimes led him astray. He became

too sympathetic to the Hindu nationalism that is now poisoning India

politics, as if a whole Hindu civilization were on the rise after

centuries of alien Muslim or Western despoliations.

There is no such thing as a whole civilization.

But some of Naipaul’s greatest literature came out of his yearning

for it. Although he may, at times, have associated this with

England or India, his imaginary civilization was not tied to

any nation. It was a literary idea, secular, enlightened, passed

on through writing. That is where he made his home, and that is where,

in his books, he will live on.

August 13, 2018, 1:39 pm

Aug 16th 2018

https://www.economist.com/…/…/vs-naipaul-died-on-august-11th

No settled place!

HE WAS struck again and again by the wonder of being in his own house, the audacity of it: to walk down a farm track in Wiltshire to his own front gate, to close his doors and windows on his own space, privacy and neatness, to walk on cream carpet through book-lined rooms where, still in a towelling robe at noon, he could summon a wife to make coffee or take dictation. Outside, he could wander over lawns to the manor house, or a lake where swans glided, or visit the small building that served as his wine cellar. Vidia, his friends called him; he disliked his name, but liked the derivation, from the Sanskrit for seeing and knowing. He looked hard, with his eagle stare, and saw things as they were.

The house, which he rented, was paid for by his books, more than 30 of them. He had not taken up writing to get rich or win awards; that was a dreadful thought. Dreadful! To write was a vocation. Nonetheless his fourth book, “A House for Mr Biswas”, based on his father’s search for a settled place, had luckily propelled him to fame, and in 2001 he had won the Nobel prize for literature. He had been knighted, too, though he did not care to use the title. Hence the country cottage, as well as a duplex in Chelsea. For, as Mr Biswas said, “how terrible it would have been…to have lived without even attempting to lay claim to one’s portion of the earth.”

Which portion of the earth, though, was the question. Mr Naipaul’s ancestors were Indian, but that part lay in darkness, pierced only by his grandmother’s prayers and quaint rituals of eating. Journeys to India later, which resulted in three books excoriating the place, convinced him that this was not his home and never could be. He was repelled by the slums, the open defecation (picking his fastidious way through butts and twists of human excrement), and by the failure of Indian civilisation to defend itself. His place of birth and growth was Trinidad, principally Port of Spain, the humid, squalid, happy-go-lucky city, sticky with mangoes and loud with the beat of rain on corrugated iron, that provided the comedy in “Biswas” and “Miguel Street”. But he had to leave. England was his lure, as for all bright colonial boys who did not know their place, and his Trinidadian accent soon vanished in high-class articulation; but Oxford was wretched and London disappointing. He kept leaving, travelling, propelled by restlessness. Books resulted, but not calm. Not calm.

Much of his agitation, even to tears, came from the urge to write itself; what he was to write about, and in what form. The novel was exhausted. Modernism was dead. Yet literature had taken hold of him, a noble purpose to his life, the call of greatness. He had moved slowly into writing, first fascinated by the mere shapes of the letters, requesting pens, Waterman ink and ruled exercise books to depict them; then intrigued by the stories his father read to him; then, in London, banging out his first attempts on a BBC typewriter. For a long time he failed to devise a story. Beginnings were laborious, punctuation sacred: he filleted an American editor for removing his semicolons, “with all their different shades of pause”. Once going, though, he wrote at speed, hoping to reach that state of exaltation when he would understand himself, as well as his subject.

Truth-telling, defying the darkness, was his purpose. His travels through the post-colonial world, to India, Africa, the Caribbean and South America, made him furious: furious that formerly colonised peoples were content to lose their history and dignity, to be used and abandoned, and to build no institutions of their own, like the Africans of “In a Free State” squealing in their forest-language in the kitchens of tourist hotels. He mourned the relics of colonial rule, the overgrown gardens and collapsed polo pavilions, the mock-Tudor lodges and faded Victorian bric-à-brac he saw in Bundi or Kampala; but even more than these, the loss of human potential.

Many people were offended, and he cared not a whit whether they were or not. It was his duty and his gift to describe things exactly: whether the marbled endpaper of a dusty book, the stink of bed bugs and kerosene, the way that purple jacaranda flowers shone against rocks after rain, or the stupidity of most people. He resisted all editing, of writing or opinions. Without apology, he also slapped his mistress once until his hand hurt. Severity and pride came naturally to his all-seeing self.

To the plantation

The further purpose of writing was to give order to his life. He carefully recorded all events, either in his memory for constant replays or in small black notebooks consigned to his inside jacket pocket. Converting these to prose imposed a shape on disorder; it provided a structure, a shelter, protection. His rootless autobiographical heroes often dreamed of such calm places: a cottage on a hill, with a fire lit, approached at night through rain; a room furnished all in white, looking towards the sea; or in “The Mimic Men” the most alluring vision, an estate house on a Caribbean island among cocoa groves and giant immortelle trees, whose yellow and orange flowers floated down on the woods. Though he ended his days in Wiltshire, more or less content, it was somebody else’s sun he saw there, and somebody else’s history. His deep centre remained the place from which he had fled.

Note: Bài ai điếu quá tuyệt. Bài sau

đây, cũng không thua.

https://www.nybooks.com/…/v-s-naipaul-poet-of-the-displaced/

Naipaul thi sĩ bán xới [không

có 1 nơi chốn để mà cắm dùi]

V.S. Naipaul’s fastidiousness was legendary. I met him for the first time in Berlin, in 1991, when he was feted for the German edition of his latest book. A smiling young waitress offered him some decent white wine. Naipaul took the bottle from her hand, examined the label for some time, like a fine-art dealer inspecting a dubious piece, handed the bottle back, and said with considerable disdain: “I think perhaps later, perhaps later.” (Naipaul often repeated phrases.)

This kind of thing also found its way into his travel writing. He could work himself up into a rage about the quality of the towels in his hotel bathroom, or the slack service on an airline, or the poor food at a restaurant, as though these were personal affronts to him, the impeccably turned-out traveler.

Naipaul was nothing if not self-aware. In his first travel account of India, An Area of Darkness (1964), he describes a visit to his ancestral village in a poor, dusty part of Uttar Pradesh, where an old woman clutches Naipaul’s shiny English shoes. Naipaul feels overwhelmed, alienated, presumed upon. He wants to leave this remote place his grandfather left behind many years before. A young man wishes to hitch a ride to the nearest town. Naipaul says: “No, let the idler walk.” And so, he adds, “the visit ended, in futility and impatience, a gratuitous act of cruelty, self-reproach and flight.”

It is tempting to see Naipaul as a blimpish figure, aping the manners of British bigots; or as a fussy Brahmin, unwilling to eat from the same plates as lower castes. Both views miss the mark. Naipaul’s fastidiousness had more to do with what he called the “raw nerves” of a displaced colonial, a man born in a provincial outpost of empire, who had struggled against the indignities of racial prejudice to make his mark, to be a writer, to add his voice to what he saw as a universal civilization. Dirty towels, bad service, and the wretchedness of his ancestral land were insults to his sense of dignity, of having overcome so much.

These raw nerves did not make him into an apologist for empire, let alone for the horrors inflicted by white Europeans. On the contrary, he blamed the abject state of so many former colonies on imperial conquest. In The Loss of Eldorado (1969), a short history of his native Trinidad, he describes in great detail how waves of bloody conquest wiped out entire peoples and their cultures, leaving half-baked, dispossessed, rootless societies. Such societies have lost what Naipaul calls their “wholeness” and are prone to revolutionary fantasies and religious fanaticism.

Wholeness was an important idea to Naipaul. To him, it represented cultural memory, a settled sense of place and identity. History was important to him, as well as literary achievement upon which new generations of writers could build. It irked him that there was nothing for him to build on in Trinidad, apart from some vaguely recalled Brahmin rituals and books about a faraway European country where it rained all the time, a place he could only imagine. England, to him, represented a culture that was whole. And, from the distance of his childhood, so did India. (In fact, he knew more about ancient Rome, taught by a Latin teacher in Trinidad, than he did about either country.)

When he finally managed to go to India, he was disappointed. India was a “wounded civilization,” maimed by Muslim conquests and European colonialism. He realized he didn’t belong there, any more than in Trinidad or in England. And so he sought to find his place in the world through words. Books would be his escape from feeling rootless and superfluous. His father, Seepersad Naipaul, had tried to lift himself from his surroundings by writing journalism and short stories, which he hoped, in vain, to publish in England. Writing, to father and son, was more than a profession; it was a calling that conferred a kind of nobility.

Naipaul’s most famous novel, A House for Mr. Biswas (1961), drew on the father’s story of frustrated ambition. By going back into the world of his childhood, he found the words to create his own link to that universal literary civilization. He often told interviewers that he only existed in his books.

If raw nerves made him irascible at times, they also sharpened his vision. He understood people who were culturally dislocated and who tried to find solace in religious or political fantasies that were often borrowed from other places and ineptly mimicked. He described such delusions precisely and often comically. His sense of humor sometimes bordered on cruelty, and in interviews with liberal journalists it could take the form of calculated provocation. But his refusal to sentimentalize the wounds in postcolonial societies produced some of his most penetrating insights.

My favorite book by Naipaul is not A House for Mr. Biswas, or the later novel A Bend in the River (1979), his various books on India, or even his 1987 masterpiece The Enigma of Arrival, but a slender volume entitled Finding the Center (1984). It consists of two long essays, one about how he learned to become a writer, how he found his own voice, and the other about a trip to Ivory Coast in 1982. In the first piece, written out of unflinching self-knowledge, he gives a lucid account of the way he sees the world, and how he puts this in words. He travels to understand himself, as well as the politics and histories of the countries he visits. Following random encounters with people who interest him, he tries to understand how people see themselves in relation to the world they live in. But by doing so, he finds his own place, too, in his own inimitable words.

The second part of Finding the Center, called “The Crocodiles of Yamassoukro,” is a perfect example of his methods. It is a surprisingly sympathetic account of a messed-up African country, filled with foreigners as well as local people wrapped up in a variety of self-told stories, some of them fantastical, about how they see themselves fitting in. African Americans come in search of an imaginary Africa. A black woman from Martinique escapes in a private world of quasi-French snobbery. And the Africans themselves, in Naipaul’s vision, have held onto a “whole” culture under a thin layer of false mimicry. This culture of ancestral spirits comes alive at night, when the gimcrack modernity of daily urban life is forgotten.

Being in Africa reminds him of his childhood in Trinidad,

when descendants of slaves turned the world upside down in carnivals,

in which the oppressive white world ceased to exist and they reigned as

African kings and queens. It is an oddly romantic vision of African life,

this idea that something whole lurks under the surface of a half-made,

borrowed civilization. Perhaps it is more telling of Naipaul’s own longings

than of the reality of most people’s lives. If he is always clear-eyed

about the pretentions of religious fanatics, Third World mimic men, and

delusional political figures, his idea of wholeness can sound almost sentimental.

David Levine

V.S. Naipaul

I remember being in a car with Naipaul one summer day in Wiltshire, England, near the cottage where he lived. He told me about his driver, a local man. The driver, he said, had a special bond with the rolling hills we were passing through. The man was aware of his ancestors buried under our feet. He belonged here. He felt the link with generations that had been here before him: “That is how he thinks, that is how he thinks.”

I am not convinced at all that this was the way Naipaul’s driver thought. But it was certainly the way he thought in the writer’s imagination. Naipaul was our greatest poet of the half-baked and the displaced. It was the imaginary wholeness of civilizations that sometimes led him astray. He became too sympathetic to the Hindu nationalism that is now poisoning India politics, as if a whole Hindu civilization were on the rise after centuries of alien Muslim or Western despoliations.

There is no such thing as a whole civilization. But some

of Naipaul’s greatest literature came out of his yearning for it. Although

he may, at times, have associated this with England or India, his imaginary

civilization was not tied to any nation. It was a literary idea, secular,

enlightened, passed on through writing. That is where he made his home,

and that is where, in his books, he will live on.

August 13, 2018, 1:39 pm

https://www.theguardian.com/…/vs-naipaul-nobel-prize-winnin…

Trinidad-born author won both acclaim and disdain for his caustic portrayals, in novels and non-fiction, of the legacy of colonialism

Nhà văn Ấn Độ, sinh tại Trinidad, được

khen, cũng dữ, và chửi, cũng chẳng thua, do cái sự miêu

tả cay độc của ông ta, trong cả giả tưởng lẫn không giả

tưởng, di sản của chủ nghĩa thực dân thuộc địa

Naipaul là 1 tác giả quá

quen thuộc với độc giả Tin Văn. Ngay khi ông được Nobel, là

GCC đã dịch và giới thiệu 1 truyện ngắn của ông trong

Phố Miguel, và sau đó, dịch bài diễn văn Nobel.

Mới đây nhất, là bài viết- mới đi được 1 mẩu - của

James Wood, “Wounder and Wounded” [Kẻ làm kẻ khác bị thương,

và bị thương]. Nay, bèn lôi ra, đốt trọn nén

nhang vĩnh biệt ông.

http://www.tanvien.net/D_1/19.html

“The politics

of a country can only be an extension of its idea about human relationships”

Naipaul. Pankaj Mishra trích dẫn trong The Writer and the World. Introduction.

"The most splendid

writer of English alive today ....

He looks into the mad eye of history and does not blink."

-THE BOSTON

GLOBE

Note: Bài viết này,

được 1 bạn văn đăng lại,

trên blog của anh, thành thử Gấu phải “bạch hóa”

mấy cái tên viết tắt, cho dễ hiểu, và nhân

tiện, đi thêm 1 đường về Naipaul.

Ông này cũng thuộc thứ cực độc, nhưng quả là

1 đại sư phụ. TV sẽ đi bài của Bolano viết về ông, đã

giới thiệu trên TV, nhưng chưa có bản dịch.

Bài viết này,

theo GCC, đến lượt nó, qua khứu giác của Bolano, làm bật ra con thú ăn thịt người nằm sâu

trong 1 tên…. Bắc Kít!

Bằng

cách nào tôi bỏ Phố Miguel ( V.S.Naipaul)

Tớ sinh ra ở đó, nhưng đúng là

1 lỗi lầm. Naipaul nói về nơi ông sinh ra, Trinidad, và

ông sẽ tự tử, nếu không bỏ đi được. Một người bạn của ông

đã làm như vậy.

The public snob, the grand bastard, was much

in evidence when I interviews V. S. Naipaul in 1994, and this was exactly

as expected. A pale woman, his secretary, showed me in to the sitting

room of his London flat. Naipaul looked warily at me, offered a hand, and

began an hour of scornful correction. I knew nothing, he said, about his

birthplace, Trinidad; I possessed the usual liberal sentimentality. It

was a slave society, a plantation. Did I know anything about his writing?

He doubted it. The writing life had been desperately hard. But hadn't his

great novel, A House for Mr. Biswas, been acclaimed on its publication, in

1961? "Look at the lists they made at the end of the 1960s of the best books

of the decade. Biswas is not there. Not there." His secretary brought coffee

and retired. Naipaul claimed that he had not even been published in America

until the 1970s “and then the reviews were awful-unlettered, illiterate, ignorant.”

The phone rang, and kept ringing. "I am sorry," Naipaul said in exasperation,

"one is not well served here." Only as the pale secretary showed me out,

and novelist and servant briefly spoke to each other in the hall, did I realize

that she was Naipaul's wife.

A few days later, the phone rang. "It's Vidia

Naipaul. I have just read your ... careful piece in The Guardian. Perhaps

we can have lunch. Do you know the Bombay Brasserie? What about one o'clock

tomorrow?| The Naipaul who took me to lunch that day was different

[còn tiếp]

James Wood: The Fun Stuff

Typical sentence

Easier to pick two of them. What’s most typical is the way one sentence qualifies another. “The country was a tyranny. But in those days not many people minded.” (“A Way in the World”, 1994.)

Câu văn điển hình:

Dễ kiếm hai câu, điển hình nhất, là cái

cách mà câu này nêu phẩm chất câu

kia:

"Xứ sở thì là bạo chúa. Nhưng những ngày

này, ít ai "ke" chuyện này!"

Naipaul rất tởm cái gọi là quê hương là chùm kế ngọt của ông. Khi được hỏi, giá như mà ông không chạy trốn được quê hương [Trinidad] của mình, thì sao, ông phán, chắc nịch, thì tao tự tử chứ sao nữa! (1)

Tuyệt.

INTERVIEWER

Do you ever wonder what would have become of you if you had stayed in Trinidad?

NAIPAUL

I would have killed myself. A friend of mine did-out of stress, I think. He was a boy of mixed race. A lovely boy, and very bright. It was a great waste.

Sir V.S. Naipaul (1932- ): Nobel văn chương

2001

“Con người và nhà

văn là một. Đây là phát giác lớn lao

nhất của nhà văn. Phải mất thời gian – và biết bao là

chữ viết! – mới nhập một được như vậy.”

(Man and writer were the

same person. But that is a writer’s greatest discovery. It took time –

and how much writing! – to arrive at that synthesis)

V.S. Naipaul, “The Enigma

of Arrival”

Trong bài tiểu luận “Lời

mở đầu cho một Tự thuật” (“Prologue to an Autobiography”), V.S. Naipaul

kể về những di dân Ấn độ ở Trinidad. Do muốn thoát ra khỏi

vùng Bắc Ấn nghèo xơ nghèo xác của thế kỷ 19,

họ “đăng ký” làm công nhân xuất khẩu, tới một

thuộc địa khác của Anh quốc là Trinidad. Rất nhiều người

bị quyến rũ bởi những lời hứa hẹn, về một miếng đất cắm dùi sau khi

hết hợp đồng, hay một chuyến trở về quê hương miễn phí, để

xum họp với gia đình. Nhưng đã ra đi thì khó

mà trở lại. Và Trinidad tràn ngập những di dân

Ấn, không nhà cửa, không mảy may hy vọng trở về.

Vào năm 1931, con tầu SS Ganges đã đưa một ngàn

di dân về Ấn. Năm sau, trở lại Trinidad, nó chỉ kiếm được

một ngàn, trong số hàng ngàn con người không

nhà nói trên. Ngỡ ngàng hơn, khi con tầu tới

cảng Calcutta, bến tầu tràn ngập những con người qui cố hương chuyến

đầu: họ muốn trở lại Trinidad, bởi vì bất cứ thứ gì họ nhìn

thấy ở quê nhà, dù một tí một tẹo, đều chứng

tỏ một điều: đây không phải thực mà là mộng.

Ác mộng.

“Em ra đi nơi này vẫn

thế”. Ngày nay, du khách ghé thăm Bắc Ấn, nơi những

di dân đợt đầu tiên tới Trinidad để lại sau họ, nó

chẳng khác gì ngày xa xưa, nghĩa là vẫn nghèo

nàn xơ xác, vẫn những con đường đầy bụi, những túp

lều tranh vách đất, lụp xụp, những đứa trẻ rách rưới, ngoài

cánh đồng cũng vẫn cảnh người cày thay trâu… Từ vùng

đất đó, ông nội của Naipaul đã được mang tới Trinidad,

khi còn là một đứa bé, vào năm 1880. Tại

đây, những di dân người Ấn túm tụm với nhau, tạo thành

một cộng đồng khốn khó. Vào năm 1906, Seepersad, cha của

Naipaul, và bà mẹ, sau khi đã hoàn tất thủ

tục hồi hương, đúng lúc tính bước chân xuống

tầu, cậu bé Seepersad bỗng hoảng sợ mất vía, trốn vào

một xó cầu tiêu công cộng, len lén nhìn

ra biển, cho tới khi bà mẹ thay đổi quyết định.

Chính là

nỗi đau nhức trí thức thuộc địa, chính nỗi chết không

rời đó, tẩm thấm mãi vào mình, khiến cho

Naipaul có được sự can đảm để làm một điều thật là

giản dị: “Tôi gọi tên em cho đỡ nhớ”.

Em ở đây, là đường phố Port of Spain, thủ phủ Trinidad. Khó khăn, ngại ngùng, và bực bội – dám nhắc đến tên em – mãi sau này, sau sáu năm chẳng có chút kết quả ở Anh Quốc, vẫn đọng ở nơi ông, ngay cả khi Naipaul bắt đầu tìm cách cho mình thoát ra khỏi truyền thống chính quốc Âu Châu, và tìm được can đảm để viết về Port of Spain như ông biết về nó. Phố Miguel (1959), cuốn sách đầu tiên của ông được xuất bản, là từ quãng đời trẻ con của ông ở Port of Spain, nhưng ở trong đó, ông đơn giản và bỏ qua rất nhiều kinh nghiệm. Hồi ức của những nhân vật tới “từ một thời nhức nhối. Nhưng không phải như là tôi đã nhớ. Những hoàn cảnh của gia đình tôi quá hỗn độn; tôi tự nhủ, tốt hơn hết, đừng ngoáy sâu vào đó."

Comments

Post a Comment