"Un homme est passé"

Phim này cũng

thật tuyệt. Gấu xem hồi còn nhỏ, và nhớ hoài. Trong có chi tiết thần

sầu, mà có

thể Kim Dung đã từng thuổng. Cái chi tiết mà nhờ nó, Ðoàn Dự khám phá

ra bí mật

sau núi Vô Lượng, tìm được đường vô hang động bí mật, gặp pho tượng mỹ

nhân giống

hệt em Vương Ngọc Yến, học được chiêu Lăng Ba Vi Bộ, sau truyền lại cho

Gấu Nhà

Văn, áp dụng vào những bài viết không ai lần ra cấu trúc của chúng!

Hà, hà!

Ðúng như thế,

một bạn văn, lần đầu đọc bài viết về Võ Phiến, cứ

lẩm bẩm, ông

này viết ngược ngạo, như thể lầm đoạn trên với đoạn dưới, rồi sau đó

lại lầm đoạn

dưới với đoạn trên, nhưng sau vỡ ra, lại khen tới chỉ, văn viết như tơ,

như lụa,

không biết làm sao mà lần…

[Nguyên văn:

Cấu trúc bài viết vừa rồi của chú dù chia phần rõ vẫn rất lạ. Lúc đầu

N. tưởng

bị lẫn đoạn. Đó là cấu trúc của thơ. Trong đó có những suy diễn rất

thích.]

Ui chao, lại

tự thổi!

Gấu sử dụng,

cũng cấu trúc đó, viết Một Chuyến Ði, được cả băng VH

khen là tuyệt chiêu, và

nhà phê bình gia của băng nhận ra, và chỉ đích danh, đây là chiêu Lăng

Ba Vi Bộ của Kim Dung!

Tuyệt nhất,

là được 1 vị độc giả khen, bài viết tuyệt quá. Gấu phổng mũi, post liền

cái

mail, thế là vị này từ luôn Gấu. Không thèm mail nữa. Gấu hoảng quá,

không biết

chuyện gì xẩy ra, sau cùng vị này thương tình, đi 1 cái mail chót, ta

vẫn bình

thường, mi khỏi phải lo cho ta…

Tks, and

take care. Bye. NQT

Phim này cũng thật là tuyệt.

"Distance is the soul of beauty”. Simone Weil.

Cái tuyệt của phim này, hay, linh hồn của cái đẹp của nó, là khoảng cách giữa hai lần coi. Lần đầu Gấu coi, tuyệt, nhưng khác lần coi sau này. Y chang nghe nhạc sến ở trong tù VC!

Hình như Gấu đã kể về cái lần nghe bản “Xe lăn trong tim”, tức bản “Chuyến tầu hoàng hôn”, ở Ðỗ Hòa?

Cái tay bảo vệ nông trường, cũng tù, 1 anh nhóc con, chắc tù hình sự, lúc nào lúc lẩm nhẩm bài này, khi “chăn” đám tù, trong có Gấu

Tình cờ đọc

bài viết của Ngự Thuyết, và bèn nhớ ra đây

là 1 phim thần sầu!

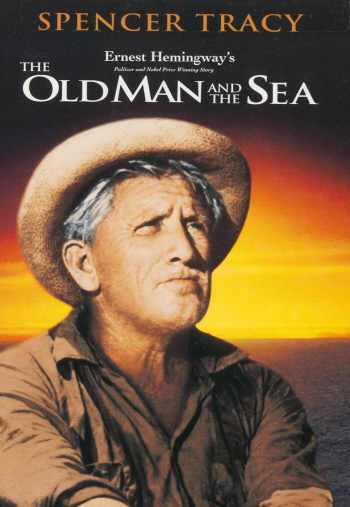

Có thể nói,

phim nào của Spencer Tracy cũng thần sầu. Ngư

ông và Biển cả, Xử án tại Nuremberg, Tuyết để tang, La neige en deuil…

Ui chao, sao lại có 1 tay diễn viên “nhân hậu” đến như thế cơ chứ.

Ðọc bài viết 1 cái là nhớ ngay ra số phận đám tù VNCH, có nhiều tên Bắc Kít, sau 30 Tháng Tư 1975, được nhà nước cho về thăm quê hương cũ!

Nhớ cái cảnh nhà thơ, chiều cuối năm đi qua 1 làng quê, và tiếp đón ông và bạn tù, là 1 lũ con nít…

Chán thật!

Ui chao, sao lại có 1 tay diễn viên “nhân hậu” đến như thế cơ chứ.

Ðọc bài viết 1 cái là nhớ ngay ra số phận đám tù VNCH, có nhiều tên Bắc Kít, sau 30 Tháng Tư 1975, được nhà nước cho về thăm quê hương cũ!

Nhớ cái cảnh nhà thơ, chiều cuối năm đi qua 1 làng quê, và tiếp đón ông và bạn tù, là 1 lũ con nít…

Chán thật!

Cái đầu quả

là hư mất rồi!

Gấu Cái cũng nhận ra điều này, mi khùng rồi.

Gấu Cái cũng nhận ra điều này, mi khùng rồi.

Note:

Có vẻ như bài viết của NT không liên can tới nội dung phim?

NQT

NQT

Trong những

bài viết về Ngư Ông, bài của

tác giả Ðời của Pi, Yann

Martel, thật tuyệt. Ông

nhìn ra cái gốc Thánh Kinh của nó.

Liu Xiaobo, Nobel Hòa Bình, phán, tớ đếch có kẻ thù, là theo nghĩa "Ngư Ông". Theo nghĩa, nhiều kẻ thù tao, cả 1 nhà nước thù tao, nhưng tao chưa kiếm ra kẻ thù, như con cá của Ngư ông.

Liu Xiaobo, Nobel Hòa Bình, phán, tớ đếch có kẻ thù, là theo nghĩa "Ngư Ông". Theo nghĩa, nhiều kẻ thù tao, cả 1 nhà nước thù tao, nhưng tao chưa kiếm ra kẻ thù, như con cá của Ngư ông.

Ui chao, đôi

khi, Gấu này "cuồng vọng", nghĩ rằng, mình có nhiều kẻ thù, nhưng chưa

gặp con cá, mà gặp con K.

[như của Buzzati]

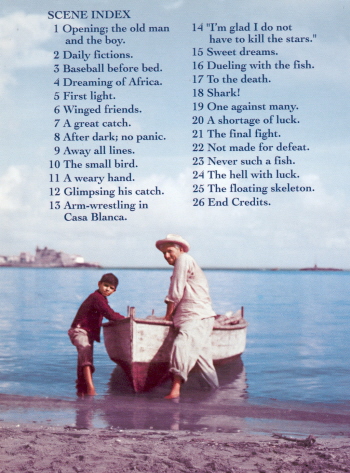

THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA

BY ERNEST HEMINGWAY

BY ERNEST HEMINGWAY

February 16, 2009

To Stephen Harper,

Prime Minister of Canada,

From a Canadian writer,

With best wishes,

Yann Martel

To Stephen Harper,

Prime Minister of Canada,

From a Canadian writer,

With best wishes,

Yann Martel

Dear Mr. Harper,

The famous Ernest Hemingway. The

Old Man and the Sea is one

of those works of literature that most everyone has heard of, even

those who

haven't read it. Despite its brevity 127 pages in the well-spaced

edition I am

sending you it's had a lasting effect on English literature, as has

Hemingway's

work in general. I'd say that his short stories, gathered in the

collections

In Our Time, Men without Women and Winner Take Nothing,

among

others, are his greatest achievement and above all, the story "Big

Two-Hearted River" but his novels The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to

Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls are more widely read.

The greatness of Hemingway lies not so much in what he said as how he said it. He took the English language and wrote it in a way that no one had written it before. If you compare Hemingway, who was born in 1899, and Henry James, who died in 1916, that overlap of seventeen years seems astonishing, so contrasting are their styles. With James, truth, verisimilitude, realism, whatever you want to call it, is achieved by a baroque abundance of language. Hemingway's style is the exact opposite. He stripped the language of ornamentation, prescribing adjectives and adverbs to his prose the way a careful doctor would prescribe pills to a hypochondriac. The result was prose of revolutionary terseness, with a cadence, vigor and elemental simplicity that bring to mind a much older text: the Bible.

That combination is not fortuitous. Hemingway was well versed in biblical language and imagery and The Old Man and the Sea can be read as a Christian allegory, though I wouldn't call it a religious work, certainly not in the way the book I sent you two weeks ago, Gilead, is. Rather, Hemingway uses Christ's passage on Earth in a secular way to explore the meaning of human suffering. "Grace under pressure" was the formulation Hemingway offered when he was asked what he meant by "guts" in describing the grit shown by many of his characters. Another way of putting that would be the achieving of victory through defeat, which matches more deeply, I think, the Christ-like odyssey of Santiago, the old man of the title. For concerning Christ, that was the Apostle Paul's momentous insight (some would call it God's gift): the possibility of triumph, of salvation, in the very midst of ruination. It's a message, a belief that transforms the human experience entirely. Career failures, family disasters, accidents, disease, old age-these human experiences that might otherwise be tragically final instead become threshold events.

As I was thinking about Santiago and his epic encounter with the great marlin, I wondered whether there was any political dimension to his story. I came to the conclusion that there isn't. In politics, victory comes through victory and defeat only brings defeat. The message of Hemingway's poor Cuban fisherman is purely personal, addressing the individual in each one of us and not the roles we might take on. Despite its vast exterior setting, The Old Man and the Sea is an intimate work of the soul. And so I wish upon you what I wish upon all of us: that our return from the high seas be as dignified as Santiago's.

Yours truly, Yann Martel

ERNEST

HEMINGWAY

(I899-1961) was an American journalist, novelist and short story

writer. He is

internationally acclaimed for his works The Sun Also Rises, A

Farewell to Arms,

For Whom the Bell Toll and his Pulitzer Prize-winning novella,

The Old

Man and the Sea.The greatness of Hemingway lies not so much in what he said as how he said it. He took the English language and wrote it in a way that no one had written it before. If you compare Hemingway, who was born in 1899, and Henry James, who died in 1916, that overlap of seventeen years seems astonishing, so contrasting are their styles. With James, truth, verisimilitude, realism, whatever you want to call it, is achieved by a baroque abundance of language. Hemingway's style is the exact opposite. He stripped the language of ornamentation, prescribing adjectives and adverbs to his prose the way a careful doctor would prescribe pills to a hypochondriac. The result was prose of revolutionary terseness, with a cadence, vigor and elemental simplicity that bring to mind a much older text: the Bible.

That combination is not fortuitous. Hemingway was well versed in biblical language and imagery and The Old Man and the Sea can be read as a Christian allegory, though I wouldn't call it a religious work, certainly not in the way the book I sent you two weeks ago, Gilead, is. Rather, Hemingway uses Christ's passage on Earth in a secular way to explore the meaning of human suffering. "Grace under pressure" was the formulation Hemingway offered when he was asked what he meant by "guts" in describing the grit shown by many of his characters. Another way of putting that would be the achieving of victory through defeat, which matches more deeply, I think, the Christ-like odyssey of Santiago, the old man of the title. For concerning Christ, that was the Apostle Paul's momentous insight (some would call it God's gift): the possibility of triumph, of salvation, in the very midst of ruination. It's a message, a belief that transforms the human experience entirely. Career failures, family disasters, accidents, disease, old age-these human experiences that might otherwise be tragically final instead become threshold events.

As I was thinking about Santiago and his epic encounter with the great marlin, I wondered whether there was any political dimension to his story. I came to the conclusion that there isn't. In politics, victory comes through victory and defeat only brings defeat. The message of Hemingway's poor Cuban fisherman is purely personal, addressing the individual in each one of us and not the roles we might take on. Despite its vast exterior setting, The Old Man and the Sea is an intimate work of the soul. And so I wish upon you what I wish upon all of us: that our return from the high seas be as dignified as Santiago's.

Yours truly, Yann Martel

Hemingway's writing style is characteristically straightforward and understated, featuring tightly constructed prose. He drove an ambulance in World War I, and was a key figure in the circle of expatriate-artists and writers in Paris in the 1920s

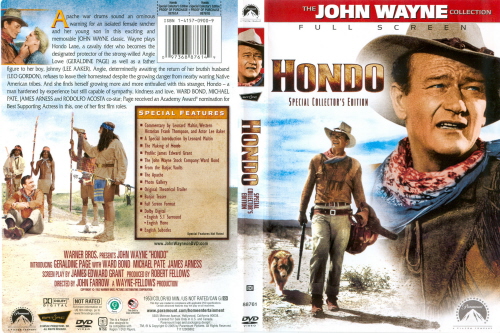

Hồi mới lớn

trong thành phố Sài Gòn, Gấu rất mê coi phim, nhất là phim cao bồi.

Bạn Ngự

Thuyết chắc là trạc tuổi Gấu, và những phim cao bồi với những

tít bằng

tiếng Tây, chỉ đến khi ra hải ngoại, tái định cư tại một vùng Bắc Mỹ,

là

Canada, thì Gấu mới biết được những cái tên nguyên thuỷ bằng tiếng Anh

của nó.

Còi xe lửa sẽ thét ba lần, Le Train sifflera

trois fois, đã thú, nhưng biết được cái tên High Noon

[1952] thì quá thú.

Rồi L’homme des vallées perdues/Shane [1953] mà chẳng sướng sao?

Rồi L’homme des vallées perdues/Shane [1953] mà chẳng sướng sao?

James Greene,

trong lời người dịch [Translatror’s

Preface] khi dịch thơ của Osip Mandelstam

qua tiếng Anh, đã coi nguyên tác & bản dịch giống như vợ/chồng, và

ông đặt

vấn đề, một liên hệ như thế, thì cần “trung thực”, hay là “vô tư”

[faithful or

free]?

Như món quà, “thơ”, ra hải

ngoại mới được hưởng, 1 lần tình cờ dạo

qua 1 con hẻm, passage, y hệt passade Eden, ở downtown Toronto, Gấu

khám phá ra

1 cái mỏ phim cũ, nhờ vậy được thưởng thức những phim cao bồi mà Gấu

chưa từng

được coi khi còn trẻ.

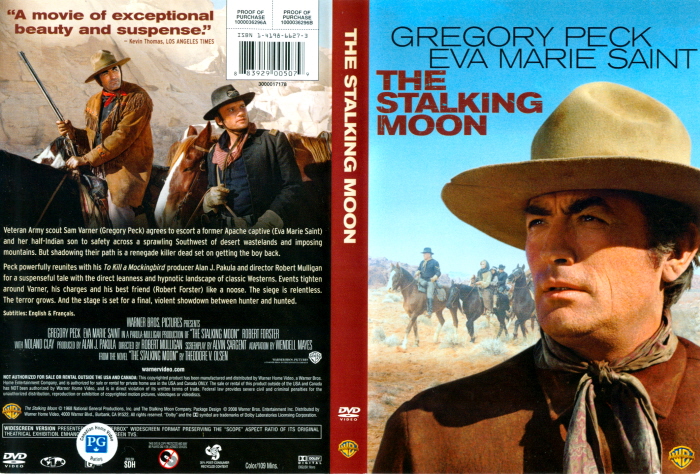

Trong có phim The Stalking Moon, dưới đây

Trong có phim The Stalking Moon, dưới đây

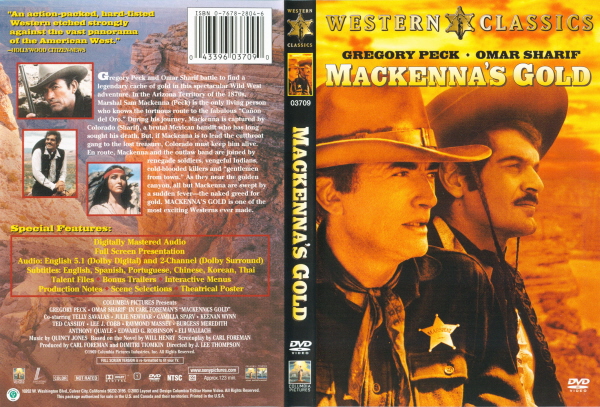

Em Evà này,

chắc là nhiều cư dân Sài Gòn còn nhớ, đã từng đóng chung với Marlon

Brando,

trong 1 phim trứ danh Sur Les Quais,

On the waterfront, Phu

Bến Tầu, một phim của

Kazan. Còn Peck, thì lại quá nổi với những vai ký giả, nhất là trong

phim Nghỉ

Hè ở La Mã, chung với “công chúa” Audrey Hepburn.

Comments

Post a Comment