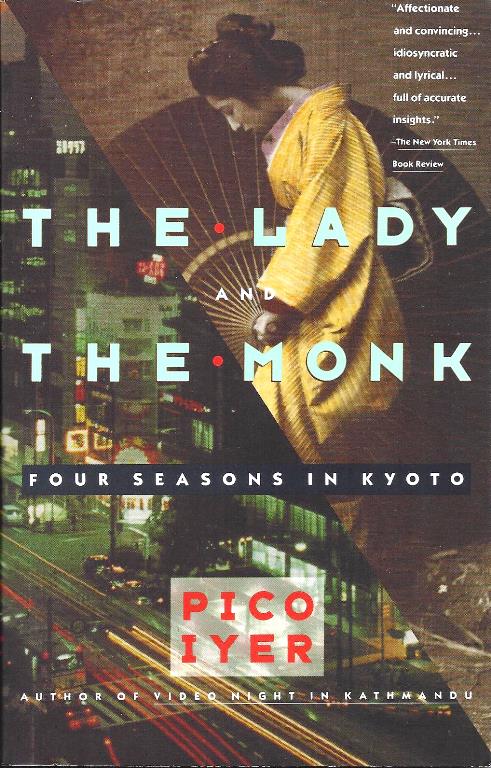

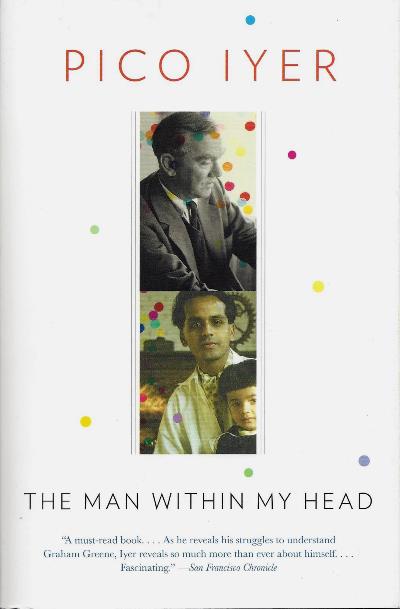

Pico Iyer

Cả cuốn truyện là từ đó mà ra. Và nó còn tiên tri ra được cuộc xuất cảng người phụ nữ Mít cả trước và sau cuộc chiến, đúng như lời anh ký giả Hồng Mao ghiền khuyên Pyle, mi hãy quên “lực lượng thứ ba” và đem Phượng về Mẽo, quên cha luôn cái xứ sở khốn kiếp Mít này đi!

Một tên Yankee mũi lõ tới một nơi ở hải ngoại, đầu đầy ắp những ý tưởng về dân chủ và như thế nào, anh ta sẽ dậy một nền văn hóa cũ kỹ, cổ xưa, hết thời rồi một cách bảnh hơn - thì cứ nói huỵch toẹt ra ở đây, đường lối, cách hành xử, lối sống Mẽo. Một tên Hồng Mao đợi anh ta ở đó, bảo vệ chính anh ta, trước cái ý nghĩ khùng điên ba trợn như thế, bằng cách khuyên anh ta đừng để ý đến cái gì hết. Và giữa họ là 1 em Mít thơm như Mít, sẵn sàng nghe hai anh mũi lõ khuyên bảo, và hưởng lợi được, từ cả hai

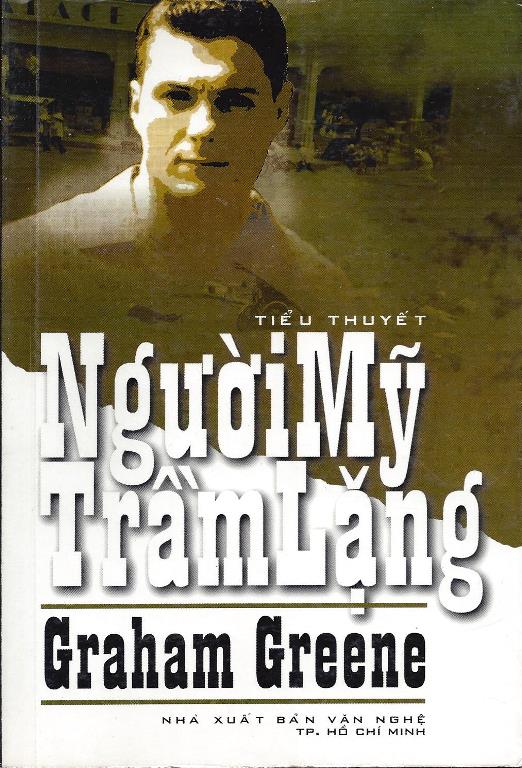

"Người Mẽo trầm lặng" của GG, được viết năm 1955, và đặt để ở Việt Nam, lúc đó là nơi đang xẩy ra cuộc nổi dậy của lực lượng bản xứ, chống lại chế độ thực dân thuộc địa của Pháp. Lồng vào, hoặc phủ lên, tam giác tình, là 1 tam giác, với ba đỉnh Mỹ, Âu và Á, với những nhân vật, như là những biểu tượng, những con người bình thường bị lôi cuốn vào đó với những đau thương, nhức nhối của họ. Lạ, là tính tiên tri của cuốn tiểu thuyết….

Nhưng đó không phải là lý do tôi đọc đi đọc lại “Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng”, như nhiều cuốn khác của GG, và luôn có nó cùng với tôi, như 1 cuốn thánh kinh cá nhân. Rõ ràng là, nếu bạn lang thang trong 1 thành phố Saigon hiện đại, như tôi đã làm, bạn có thể thấy cái tam giác tình của GG diễn ra ở mọi khách sạn khác. Và nếu bạn nghĩ đến Iraq, Afghanistan, và đâu đó, elsewhere, bạn thấy đường ven của cùng 1 câu chuyện.

Điều cuốn sách thọi tôi, sâu thẳm hơn, riêng tư hơn nhiều. Cuốn tiểu thuyết đòi hỏi mọi người trong chúng ta, muốn cái gì từ 1 nơi chốn hải ngoại, và toan tính gì với nó. Nó chỉ ra, cái ngây thơ và cái lý tưởng có thể làm thịt rất nhiều mạng người, như cái đối nghịch với nó, cái đểu cáng đáng sợ. Và nó nhắc nhở tôi rằng, thế giới thì rộng lớn nhiều so với những ý nghĩ tư tưởng của chúng ta về nó, và như thế nào, người thiếu phụ ở trong cuốn sách, cái cô Phượng, sẽ luôn luôn ở bên ngoài một vòng ôm của 1 tên mũi lõ. Nó còn ôm trọn những mảnh miểng hiểu biết - cái nền của tôi - Á, Anh, Mẽo – vào trong cùng thai đố.

Bạn phải đọc Người Mẽo trầm lặng, tôi biểu bạn bè của tôi, bởi là vì nó giải thích quá khứ của chúng ta, ở Đông Nam Á, chiếu sáng cái sự hiện diện của chúng ta ở nhiều nơi chốn, và có lẽ, báo trước tương lai của chúng ta nếu chúng ta không để ý.

Nhìn như thế, thì Diệm bị giết, phần nhiều là do thiện ý của Mẽo, hơn là do Cái Ác Bắc Kít: Nó chỉ ra, cái ngây thơ và cái lý tưởng có thể làm thịt rất nhiều mạng người, như cái đối nghịch với nó, cái đểu cáng đáng sợ.

Đọc cái lời giới thiệu mới tiếu lâm làm sao.

Graham Greene mà "bên kia chiến tuyến".

Bất giác lại nhớ đến Nguyễn Khải vs Võ Phiến, và cái sự áo thụng vái nhau, giữa nhà văn CM và nhà văn nô dịch đồi trụy Ngụy.

Cuốn NMTL khi mới ra lò là bèn bị báo chí Mẽo chửi chống Mẽo rồi.

GCC không biết Kron là ai, và mắc mớ gì tới GG.

Nhưng ông đã dũng cảm phủ nhận ngay chính mình!

Kinh thiệt!

Pico Iyer Commemorates the Centennial

of Graham Greene's Birth Oct. 6, 2004

Pico Iyer tưởng niệm GG, nhân kỷ niệm 100 năm ngày sinh của sư phụ

Pico Iyer tưởng niệm GG, nhân kỷ niệm 100 năm ngày sinh của sư phụ

An American comes into a foreign

place full of ideas of democracy and how he will teach an ancient culture

a better — in fact, an American — way of doing things. An Englishman awaits

him there, protecting himself against such foolishness by claiming to care

about nothing at all. And between them shimmers a young local woman who seems

ready to listen to either suitor, and certain to get the better of both.

The Quiet American, by Graham

Greene, was written in 1955 and set in Vietnam, then the site of a rising

local insurgency against French colonial rule. In its brilliant braiding together

of a political and a romantic tangle, its characters serve as emblems of

the American, European and Asian way, and yet ache and tremble as ordinary

human beings do. It also is a typically Greenian prophecy of what would happen

10 years later when U.S. troops would arrive, determined to teach a rich and

complex place the latest theories of Harvard Square. Lyrical, enchanted descriptions

of rice paddies, languorous opium dens and even slightly sinister Buddhist

political groups are a lantered backdrop to a tale of irony and betrayal.

But that's not why I keep reading

and rereading The Quiet American, like many of Greene's books, and have it

always with me in my carry-on, a private bible. Certainly it's true that if

you walk through modern Saigon, as I have done, you can see Greene's romantic

triangle playing out in every other hotel. And if you think about Iraq, Afghanistan,

elsewhere, you see the outline of the same story.

What touches me in the book,

though, is something even deeper and more personal. The novel asks every one

of us what we want from a foreign place, and what we are planning to do with

it. It points out that innocence and idealism can claim as many lives as

the opposite, fearful cynicism. And it reminds me that the world is much larger

than our ideas of it, and how the Vietnamese woman at the book's center, Phuong,

will always remain outside a foreigner's grasp. It even brings all the pieces

of my own background — Asian, English, American — into the same puzzle.

You must read The Quiet American,

I tell my friends, because it explains our past, in Southeast Asia, trains

light on our present in many places, and perhaps foreshadows our future if

we don't take heed. It spins a heartrending romance and tale of friendship

against a backdrop of murder, all the while unfolding a scary political parable.

And most of all, it refuses the easy answer: The unquiet Englishman isn't

as tough as he seems, and the blundering American not quite so terrible —

or so innocent. Both of them are just the people we might be at different

stages of our lives. The Quiet American, in fact, becomes most haunting and

profound if you think of it just as a dialogue between one side of Greene

— or yourself — and the other. The old in their wisdom, as he writes

elsewhere, sometimes envy the folly of the young.Một tên Yankee mũi lõ tới một nơi ở hải ngoại, đầu đầy ắp những ý tưởng về dân chủ và như thế nào, anh ta sẽ dậy một nền văn hóa cũ kỹ, cổ xưa, hết thời rồi một cách bảnh hơn - thì cứ nói huỵch toẹt ra ở đây, đường lối, cách hành xử, lối sống Mẽo. Một tên Hồng Mao đợi anh ta ở đó, bảo vệ chính anh ta, trước cái ý nghĩ khùng điên ba trợn như thế, bằng cách khuyên anh ta đừng để ý đến cái gì hết. Và giữa họ là 1 em Mít thơm như Mít, sẵn sàng nghe hai anh mũi lõ khuyên bảo, và hưởng lợi được, từ cả hai

"Người Mẽo trầm lặng" của GG, được viết năm 1955, và đặt để ở Việt Nam, lúc đó là nơi đang xẩy ra cuộc nổi dậy của lực lượng bản xứ, chống lại chế độ thực dân thuộc địa của Pháp. Lồng vào, hoặc phủ lên, tam giác tình, là 1 tam giác, với ba đỉnh Mỹ, Âu và Á, với những nhân vật, như là những biểu tượng, những con người bình thường bị lôi cuốn vào đó với những đau thương, nhức nhối của họ. Lạ, là tính tiên tri của cuốn tiểu thuyết….

Nhưng đó không phải là lý do tôi đọc đi đọc lại “Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng”, như nhiều cuốn khác của GG, và luôn có nó cùng với tôi, như 1 cuốn thánh kinh cá nhân. Rõ ràng là, nếu bạn lang thang trong 1 thành phố Saigon hiện đại, như tôi đã làm, bạn có thể thấy cái tam giác tình của GG diễn ra ở mọi khách sạn khác. Và nếu bạn nghĩ đến Iraq, Afghanistan, và đâu đó, elsewhere, bạn thấy đường ven của cùng 1 câu chuyện.

Điều cuốn sách thọi tôi, sâu thẳm hơn, riêng tư hơn nhiều. Cuốn tiểu thuyết đòi hỏi mọi người trong chúng ta, muốn cái gì từ 1 nơi chốn hải ngoại, và toan tính gì với nó. Nó chỉ ra, cái ngây thơ và cái lý tưởng có thể làm thịt rất nhiều mạng người, như cái đối nghịch với nó, cái đểu cáng đáng sợ. Và nó nhắc nhở tôi rằng, thế giới thì rộng lớn nhiều so với những ý nghĩ tư tưởng của chúng ta về nó, và như thế nào, người thiếu phụ ở trong cuốn sách, cái cô Phượng, sẽ luôn luôn ở bên ngoài một vòng ôm của 1 tên mũi lõ. Nó còn ôm trọn những mảnh miểng hiểu biết - cái nền của tôi - Á, Anh, Mẽo – vào trong cùng thai đố.

Bạn phải đọc Người Mẽo trầm lặng, tôi biểu bạn bè của tôi, bởi là vì nó giải thích quá khứ của chúng ta, ở Đông Nam Á, chiếu sáng cái sự hiện diện của chúng ta ở nhiều nơi chốn, và có lẽ, báo trước tương lai của chúng ta nếu chúng ta không để ý.

Nó kể một chuyện tình đau thương, nhức nhối, và tình bạn trên cái nền sát nhân, cùng lúc như thế đó, bèn kèm thêm bonus, là 1 ngụ ngôn chính trị khiếp đảm, cứ theo đà của cuốn truyện mà thò ra, và trên tất cả, nó từ chối 1 câu trả lời dễ dãi: Cái tên Ăng Lê không trầm lặng thì hóa ra cũng không đến nỗi dữ dằn như có vẻ, và cái tên Mẽo ngớ ngẩn thì cũng không khủng khiếp – hay ngây thơ như thế. Cả hai thì cũng có thể giống y chang chúng ta, trong những đoạn đời nào đó của mình.

"Người Mẽo Trầm Lặng", sự thực, trở thành ám ảnh nhất, sâu thẳm nhất, nếu bạn nghĩ về nó: thì cũng là 1 cuộc lèm lèm tay đôi, giữa, một bên là Greene - hay chính bạn –và một bên kia, bên khác. Cái xưa cũ ở trong minh triết của chúng, như ông ta viết, đâu đó, đôi khi thèm muốn cái điên rồ của tuổi trẻ.

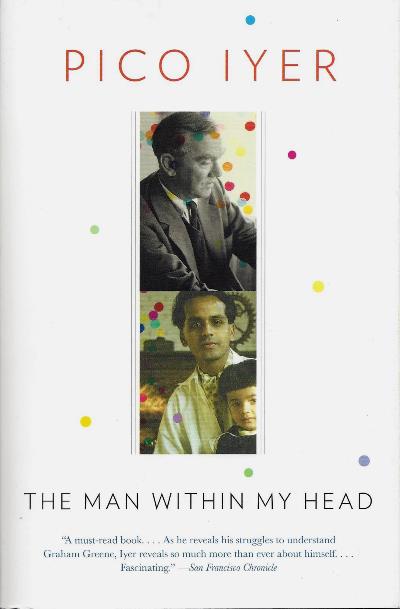

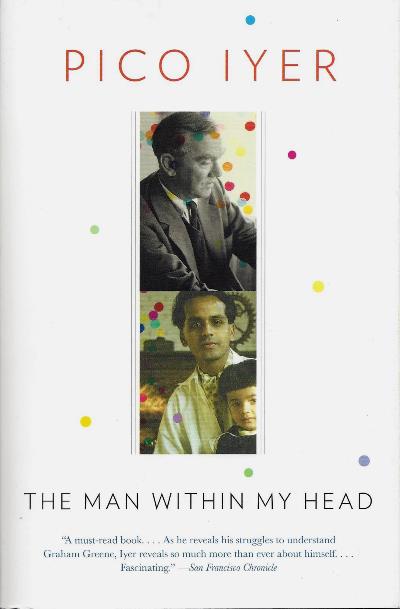

Cuốn "Người Đàn Ông Ở Trong Đầu Tôi" mở ra bằng câu:

What means the fact-which is so common-so universal-that some soul that has lost all hope for itself can inspire in another listening soul an infinite confidence in it, even while it is expressing its despair?

- HENRY DAVID THOREAU to Lucy Brown, January 24,1843

Một linh hồn mất mẹ hết mọi hy vọng về chính nó, có thể thở phào 1 phát, khi lắng nghe một linh hồn khác, và tin tưởng tuyệt đối vào linh hồn khác này, mặc dù nó đang lải nhải về nỗi chán đời của nó.

Theo GCC, cuốn NMTL được phát sinh, là từ cái tên Phượng, đúng như trong tiềm thức của Greene mách bảo ông.

Cả cuốn truyện là từ đó mà ra. Và nó còn tiên tri ra được cuộc xuất cảng người phụ nữ Mít cả trước và sau cuộc chiến, đúng như lời anh ký giả Hồng Mao ghiền khuyên Pyle, mi hãy quên “lực lượng thứ ba” và đem Phượng về Mẽo, quên cha luôn cái xứ sở khốn kiếp Mít này đi!

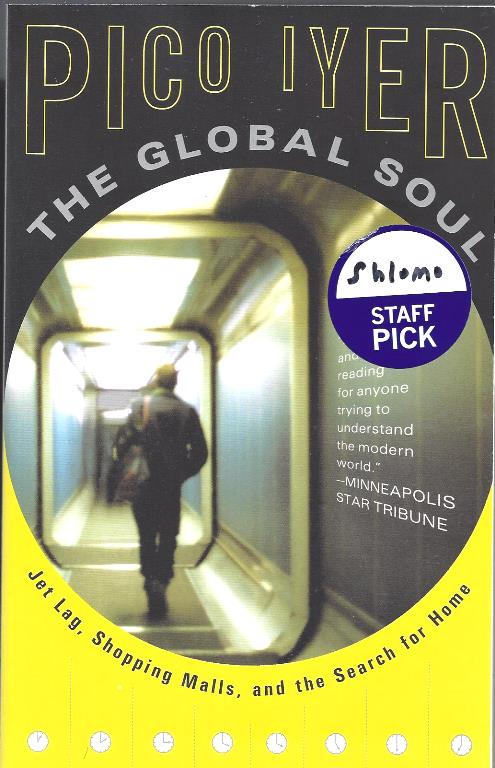

"Linh hồn viễn xứ", như "thuyền viễn xứ", có vẻ OK hơn, thay vì toàn cầu, global?

Bởi là vì nhà, ở đây, là một alien home, như tác giả giải thích

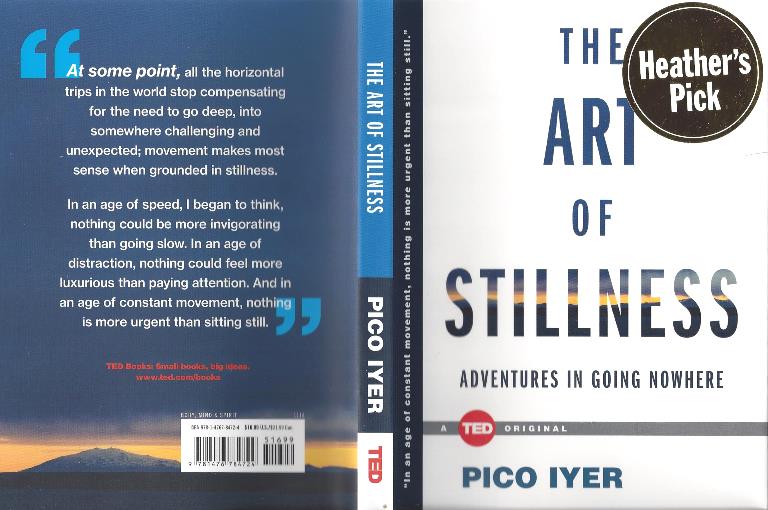

Phiêu lưu vào nơi chốn không đâu. Nghệ

thuật của sự ì ra một đống.

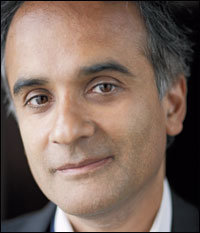

Pico Iyer là đệ tử của Graham Greene. Ông là tác giả của cuốn “Người đàn ông ở trong đầu tôi”. Người đàn ông này, là Graham Greene.

Trên TV đã giới thiệu bài viết của ông về cuốn ruột của Thầy, Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng.

Pico Iyer là đệ tử của Graham Greene. Ông là tác giả của cuốn “Người đàn ông ở trong đầu tôi”. Người đàn ông này, là Graham Greene.

Trên TV đã giới thiệu bài viết của ông về cuốn ruột của Thầy, Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng.

April 21, 2008 5:08 PM ET

An American comes into a foreign place full of ideas of democracy

and how he will teach an ancient culture a better — in fact, an American —

way of doing things. An Englishman awaits him there, protecting himself against

such foolishness by claiming to care about nothing at all. And between them

shimmers a young local woman who seems ready to listen to either suitor, and

certain to get the better of both.The Quiet American, by Graham Greene, was written in 1955 and set in Vietnam, then the site of a rising local insurgency against French colonial rule. In its brilliant braiding together of a political and a romantic tangle, its characters serve as emblems of the American, European and Asian way, and yet ache and tremble as ordinary human beings do. It also is a typically Greenian prophecy of what would happen 10 years later when U.S. troops would arrive, determined to teach a rich and complex place the latest theories of Harvard Square. Lyrical, enchanted descriptions of rice paddies, languorous opium dens and even slightly sinister Buddhist political groups are a lantered backdrop to a tale of irony and betrayal.

But that's not why I keep reading and rereading The Quiet American, like many of Greene's books, and have it always with me in my carry-on, a private bible. Certainly it's true that if you walk through modern Saigon, as I have done, you can see Greene's romantic triangle playing out in every other hotel. And if you think about Iraq, Afghanistan, elsewhere, you see the outline of the same story.

Một tên Yankee mũi lõ tới một nơi ở hải ngoại, đầu đầy ắp những ý tưởng về dân chủ và như thế nào, anh ta sẽ dậy một nền văn hóa cũ kỹ, cổ xưa, hết thời rồi một cách bảnh hơn - thì cứ nói huỵch toẹt ra ở đây, đường lối, cách hành xử, lối sống Mẽo. Một tên Hồng Mao đợi anh ta ở đó, bảo vệ chính anh ta, trước cái ý nghĩ khùng điên ba trợn như thế, bằng cách khuyên anh ta đừng để ý đến cái gì hết.

Và giữa họ là 1 em Mít thơm như Mít, sẵn sàng nghe hai anh mũi lõ khuyên bảo, và hưởng lợi được, từ cả hai

Người Mẽo trầm lặng của GG, được viết năm 1955, và đặt để ở Việt Nam, lúc đó là nơi đang xẩy ra cuộc nổi dậy của lực lượng bản xứ, chống lại chế độ thực dân thuộc địa của Pháp. Lồng vào, hoặc phủ lên, tam giác tình, là 1 tam giác, với ba đỉnh Mỹ, Âu và Á, với những nhân vật, như là những biểu tượng, những con người bình thường bị lôi cuốn vào đó với những đau thương, nhức nhối của họ. Lạ, là tính tiên tri của cuốn tiểu thuyết….

But that's not why I keep reading and rereading The Quiet American, like many of Greene's books, and have it always with me in my carry-on, a private bible. Certainly it's true that if you walk through modern Saigon, as I have done, you can see Greene's romantic triangle playing out in every other hotel. And if you think about Iraq, Afghanistan, elsewhere, you see the outline of the same story.

Nhưng đó không phải là lý do tôi đọc đi đọc lại “Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng”, như nhiều cuốn khác của GG, và luôn có nó cùng với tôi, như 1 cuốn thánh kinh cá nhân. Rõ ràng là, nếu bạn lang thang trong 1 thành phố Saigon hiện đại, như tôi đã làm, bạn có thể thấy cái tam giác tình của GG diễn ra ở mọi khách sạn khác.

Và nếu bạn nghĩ đến Iraq, Afghanistan, và đâu đó, elsewhere, bạn thấy đường ven của cùng 1 câu chuyện.

Cuộc chiến Mít, với những tội ác của nó, con số người chết, 1 đất nước ngày càng tàn tạ, mất mẹ lương tâm đạo đức, mất tất cả "cái gọi là Mít", là do VC phịa ra, rồi biến nó thành hiện thực, khởi từ "ý hướng tốt" của anh Mẽo trầm lặng, cố tìm 1 lực lượng thứ ba, không theo Tẩy, Tẫu, Mút Ku.... 1 tên Mít đúng là Mít, cho xứ Mít!

Những tài liệu, văn kiện, sự kiện liên quan tới cuộc chiến giữa anh Tẩy và Việt Minh, mới nhất, từ phía Tẩy đưa ra, mà Gấu đọc, thời gian sau này, cho thấy, cuộc chiến đó có thể tránh được, ít ra là về phía Tẩy, nhưng Vẹm, không chỉ cố tình và còn mong mỏi, làm đủ mọi cách cho nó xẩy ra, để làm cỏ sạch những đảng phái khác, mà chúng gán cho tội Việt Gian, bán nước, chưa kể những nhà ái quốc như Phạm Quỳnh, thí dụ. Bởi vì chỉ có cách đó, mới thu gom mọi quyền lực vào tay chúng.

Cũng thế là cuộc chiến thứ nhì, với Mẽo, chỉ có cách đó, mới biến cả 1 miền đất thành thù nghịch.

Cuốn Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng là 1 bằng chứng chết người, của những thiện ý, của Mỹ, khi họ nhẩy vô Miền Nam

Bắc Kít bắt đúng gân Mẽo, khi thành lập MTGP: Chỉ có cách phịa ra cuộc chiến Mít thì mới thắng nó!

Nên nhớ, lịch sử Mít đã từng xẩy ra Trịnh Nguyễn phân tranh, giữa Đàng Ngoài và Đàng Trong.

Bắc Kít thua, không làm sao lấy được Miền Nam.

Nhờ nhử Mẽo vô mà thắng!

Pico Iyer Commemorates the Centennial

of Graham Greene's Birth Oct. 6, 2004

An American comes into a foreign

place full of ideas of democracy and how he will teach an ancient culture

a better — in fact, an American — way of doing things. An Englishman awaits

him there, protecting himself against such foolishness by claiming to care

about nothing at all. And between them shimmers a young local woman who seems

ready to listen to either suitor, and certain to get the better of both.

The Quiet American, by Graham

Greene, was written in 1955 and set in Vietnam, then the site of a rising

local insurgency against French colonial rule. In its brilliant braiding together

of a political and a romantic tangle, its characters serve as emblems of

the American, European and Asian way, and yet ache and tremble as ordinary

human beings do. It also is a typically Greenian prophecy of what would happen

10 years later when U.S. troops would arrive, determined to teach a rich and

complex place the latest theories of Harvard Square. Lyrical, enchanted descriptions

of rice paddies, languorous opium dens and even slightly sinister Buddhist

political groups are a lantered backdrop to a tale of irony and betrayal.

But that's not why I keep reading

and rereading The Quiet American, like many of Greene's books, and have it

always with me in my carry-on, a private bible. Certainly it's true that if

you walk through modern Saigon, as I have done, you can see Greene's romantic

triangle playing out in every other hotel. And if you think about Iraq, Afghanistan,

elsewhere, you see the outline of the same story.

What touches me in the book,

though, is something even deeper and more personal. The novel asks every one

of us what we want from a foreign place, and what we are planning to do with

it. It points out that innocence and idealism can claim as many lives as

the opposite, fearful cynicism. And it reminds me that the world is much larger

than our ideas of it, and how the Vietnamese woman at the book's center, Phuong,

will always remain outside a foreigner's grasp. It even brings all the pieces

of my own background — Asian, English, American — into the same puzzle.

You must read The Quiet American,

I tell my friends, because it explains our past, in Southeast Asia, trains

light on our present in many places, and perhaps foreshadows our future if

we don't take heed. It spins a heartrending romance and tale of friendship

against a backdrop of murder, all the while unfolding a scary political parable.

And most of all, it refuses the easy answer: The unquiet Englishman isn't

as tough as he seems, and the blundering American not quite so terrible —

or so innocent. Both of them are just the people we might be at different

stages of our lives. The Quiet American, in fact, becomes most haunting and

profound if you think of it just as a dialogue between one side of Greene

— or yourself — and the other. The old in their wisdom, as he writes elsewhere,

sometimes envy the folly of the young.

Văn phong của Pico Iyer có nét lãng mạn nhẹ nhàng hao hao với

cái lãng mạn trong văn phong của Micheal Ondaatje.

Pico

Iyer mở ra bài viết bằng 1 câu, qua đó, có vẻ như cũng thật mê Greene

(1)

Tôi mất cả nửa đời mình để nhập

vô cuốn phúc âm nhức nhối của Graham Greene về nhân loại.

It took me half a life time to grow into Graham Greene’s anguished gospel of humanity.

It took me half a life time to grow into Graham Greene’s anguished gospel of humanity.

Tuyệt!

Tờ Brick viết

về Pico Iyer:

Pico Iyer cố làm bật G.G khỏi

hệ thống của mình bằng cách viết ba ngàn trang về G.G, với cuốn mới nhất:

“Người đàn ông trong đầu tôi”. Nhưng vưỡn thua.

Pico Iyer tried to get Graham Greene out of his system by writing three thousands pages on him, boiled down into his most recent book, The Man Within My Head (a). He still failed

Pico Iyer tried to get Graham Greene out of his system by writing three thousands pages on him, boiled down into his most recent book, The Man Within My Head (a). He still failed

“Writing is, in the end, that

oddest of anomalies: an intimate letter to a stranger.”

Viết, quái nhất trong những quái: Lá thư riêng tư cho... một kẻ lạ, người dưng, nước lã!

Viết, quái nhất trong những quái: Lá thư riêng tư cho... một kẻ lạ, người dưng, nước lã!

― Pico Iyer

“Perhaps the greatest danger

of our global community is that the person in LA thinks he knows Cambodia

because he's seen The Killing Fields on-screen, and the newcomer from Cambodia

thinks he knows LA because he's seen City of Angels on video.”

Cái nguy hiểm nhất của cộng động toàn cầu, là, ngồi ở LA phán, tớ biết Cam bốt, vì mới xem phim “Cánh đồng giết người”. Và 1 tên Cam bốt mới nhập Mẽo phán, tớ biết LA, vì mới coi video “Thành phố của những thiên thần”

Cái nguy hiểm nhất của cộng động toàn cầu, là, ngồi ở LA phán, tớ biết Cam bốt, vì mới xem phim “Cánh đồng giết người”. Và 1 tên Cam bốt mới nhập Mẽo phán, tớ biết LA, vì mới coi video “Thành phố của những thiên thần”

― Pico Iyer (1)

“Ông số 2”, ngồi ở Quận Cam, chẳng đã ngậm ngùi phán, Sài Gòn có người chết đói, ngay bên hông Chợ Bến Thành!

“Ông số 2”, ngồi ở Quận Cam, chẳng đã ngậm ngùi phán, Sài Gòn có người chết đói, ngay bên hông Chợ Bến Thành!

We all carry people inside our

heads—actors, leaders, writers, people out of history or fiction, met or unmet,

who sometimes seem closer to us than people we know.

In The Man Within My Head, Pico

Iyer sets out to unravel the mysterious closeness he has always felt with

the English writer Graham Greene; he examines Greene’s obsessions, his elusiveness,

his penchant for mystery. Iyer follows Greene’s trail from his first novel,

The Man Within, to such later classics as The Quiet American and begins to

unpack all he has in common with Greene: an English public school education,

a lifelong restlessness and refusal to make a home anywhere, a fascination

with the complications of faith. The deeper Iyer plunges into their haunted

kinship, the more he begins to wonder whether the man within his head is not

Greene but his own father, or perhaps some more shadowy aspect of himself.

Drawing upon experiences across

the globe, from Cuba to Bhutan, and moving, as Greene would, from Sri Lanka

in war to intimate moments of introspection; trying to make sense of his own

past, commuting between the cloisters of a fifteenth-century boarding school

and California in the 1960s, one of our most resourceful explorers of crossing

cultures gives us his most personal and revelatory book.

Người

Đàn Ông Trong Đầu Tôi: Đúng ra, 3 người, tác giả, ông già của tác giả, và

Greene. Đúng hơn nữa, 4 người, vì còn ông già của Greene cũng hiện diện.

John Freeman:

The Sympathizer and Nothing Ever

Dies are published fast on the heels of one another, I

wonder if you could talk about how their thinking was linked.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Both of these books come out of a line of me wanting to deal with Vietnam, and more broadly, the question of war and memory in general. The ideas in Nothing Ever Dies grew slowly—I worked on it for over a decade, but the book itself I wrote in a year. I threw out all the articles I’d written and then wrote it from scratch after I had finished The Sympathizer. Some of those ideas had filtered into the fiction—but all the work of the fiction worked itself into the writing of the nonfiction. The ambition in the back of my mind—I may not be there yet—is that I would love to be able to write fiction like criticism and criticism like fiction. I think of W.G. Sebald—a hero of mine—I can’t tell the difference in his work, whether it is fiction or nonfiction, it all feels like literature. So as I was writing these books closely together, I was doing the best to incorporate criticism into the fiction, and fiction into the criticism, so with The Sympathizer I was hoping to construct a narrator who could say dramatically very critical things, but who wouldn’t be restricted as an academic to source his beliefs. In Nothing Ever Dies, I couldn’t find a way to find a sense of humor into that book, but I really did try to take everything I had learned from the novel—narrative rhythm, for example—even working my basest unsaid feelings into the very shape of the thing. One of things I want both books to do is to move the reader both emotionally and intellectually.

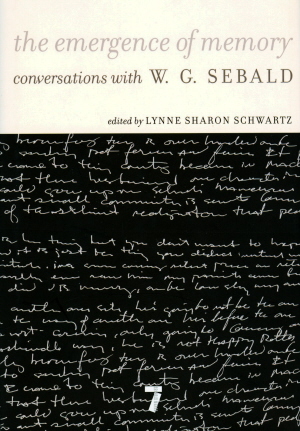

Gấu biết đến Sebald là

qua 1 bài viết của Sontag. Bà coi ông, 1 thứ nhà văn của

nhà văn. Viet Thanh Nguyen coi ông là “hero” của mình, và

rất mê lối viết trộn lẫn nhiều thể loại, phê bình, văn xuôi,

hồi tưởng…. Gấu đọc Sebald khác hẳn, một kẻ săn hồn ma, như chính

ông tự nhận, hay, với GCC, một lương tâm của nước Đức hậu chiến.

Vả chăng tuy trộn lẫn nhiều thể loại, trong khi viết giả tưởng, nhưng

với những bài viết đúng là phê bình, hay biên khảo, Sebald xuất

hiện như 1 vị quan tòa, và văn của ông, là thứ phán đoán, truy

xét, hỏi tội, Judgment. Viet Thanh Nguyen: Both of these books come out of a line of me wanting to deal with Vietnam, and more broadly, the question of war and memory in general. The ideas in Nothing Ever Dies grew slowly—I worked on it for over a decade, but the book itself I wrote in a year. I threw out all the articles I’d written and then wrote it from scratch after I had finished The Sympathizer. Some of those ideas had filtered into the fiction—but all the work of the fiction worked itself into the writing of the nonfiction. The ambition in the back of my mind—I may not be there yet—is that I would love to be able to write fiction like criticism and criticism like fiction. I think of W.G. Sebald—a hero of mine—I can’t tell the difference in his work, whether it is fiction or nonfiction, it all feels like literature. So as I was writing these books closely together, I was doing the best to incorporate criticism into the fiction, and fiction into the criticism, so with The Sympathizer I was hoping to construct a narrator who could say dramatically very critical things, but who wouldn’t be restricted as an academic to source his beliefs. In Nothing Ever Dies, I couldn’t find a way to find a sense of humor into that book, but I really did try to take everything I had learned from the novel—narrative rhythm, for example—even working my basest unsaid feelings into the very shape of the thing. One of things I want both books to do is to move the reader both emotionally and intellectually.

TV giới thiệu bài viết mới có được, về ông, nhân mới xuống phố.

Trong bài viết, trong cuốn trên, tác giả nối kết Sebald, với vụ không kích, và với Thomas Bernhard.

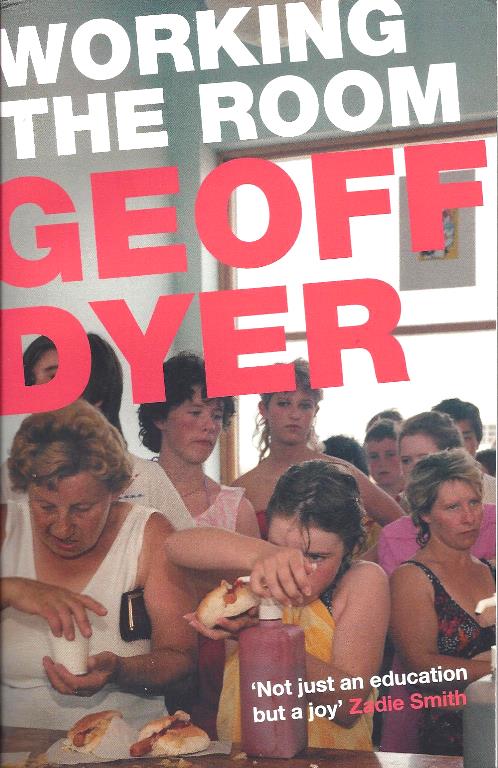

Bài viết của Dyer về Sebald xoáy vào cuốn mà Gấu mê nhất của ông, Về lịch sử tự nhiên về huỷ diệt, “On the natural history of destruction”.

TV “phải” mua cuốn sách, để “phải” đi 1 đường về Sebald, là vì bài viết này, chưa kể bài viết về “Cuộc Tình Bỏ Đi” của Scott Fitzgerald, “Tender Is the Night” [cuốn “Một Chủ Nhật Khác” là cùng dòng với nó]

On the Natural History of Destruction goes to the epicenter of ruination, examining the Allied bombardment of German cities in the Second World War. Given the scale of the calamity, Sebald asks, why have German writers been so silent about it? How had it come about that 'the sense of unparalleled national humiliation felt by millions in the last years of the war had never really found verbal expression, and that those directly affected by the experience neither shared it with each other nor passed it on to the next generation'?

Geoff Dyer: W. G. Sebald, Bombing and Thomas Bernhard

Viet Thanh Nguyen coi Sebald là “hero” của ông, vì cách viết pha trộn, nào giả tưởng, nào phê bình, hầm bà làng, như anh viết, và, nếu như thế thôi, thì, theo GCC, đọc chưa tới Sebald!

Cõi văn của Sebald, như của Kertesz, là 1 cõi đồng vọng cho “hồn thiêng” Lò Thiêu, đúng như từ của Viện Hàn Lâm ban cho ông.

Đồng Vọng cho Hồn Thiêng Lò Thiêu

http://www.tanvien.net/cn/cn_kertesz_medium.html

Ông ta viết như một hồn ma.

W.G. Sebald, Bombing and Thomas Bernhard

The first

thing to be said about W G. Sebalds books is that they always had a posthumous

quality to them. He wrote - as was often remarked - like a ghost. He was

one of the most innovative writers of the late twentieth century; and

yet part of this originality derived from the way his prose felt as if

it had been exhumed from the nineteenthGeoff Dyer

Điều đầu tiên được nói về những cuốn sách của Sebald, là chúng đều có cái air di cảo. Ông ta viết, như một hồn ma. Là 1 trong những nhà văn làm mới số 1 của hậu thế kỷ 20, tuy nhiên, 1 phần của cái uyên nguyên, là từ cái cách ông viết văn xuôi, như thể chúng được lôi lên từ cái xác thế kỷ 19!

John Freeman:

The Sympathizer and Nothing Ever Dies

are published fast on the heels of one another, I wonder if you

could talk about how their thinking was linked.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Both of these books come out of a line of me wanting to deal with Vietnam, and more broadly, the question of war and memory in general. The ideas in Nothing Ever Dies grew slowly—I worked on it for over a decade, but the book itself I wrote in a year. I threw out all the articles I’d written and then wrote it from scratch after I had finished The Sympathizer. Some of those ideas had filtered into the fiction—but all the work of the fiction worked itself into the writing of the nonfiction. The ambition in the back of my mind—I may not be there yet—is that I would love to be able to write fiction like criticism and criticism like fiction. I think of W.G. Sebald—a hero of mine—I can’t tell the difference in his work, whether it is fiction or nonfiction, it all feels like literature. So as I was writing these books closely together, I was doing the best to incorporate criticism into the fiction, and fiction into the criticism, so with The Sympathizer I was hoping to construct a narrator who could say dramatically very critical things, but who wouldn’t be restricted as an academic to source his beliefs. In Nothing Ever Dies, I couldn’t find a way to find a sense of humor into that book, but I really did try to take everything I had learned from the novel—narrative rhythm, for example—even working my basest unsaid feelings into the very shape of the thing. One of things I want both books to do is to move the reader both emotionally and intellectually.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Both of these books come out of a line of me wanting to deal with Vietnam, and more broadly, the question of war and memory in general. The ideas in Nothing Ever Dies grew slowly—I worked on it for over a decade, but the book itself I wrote in a year. I threw out all the articles I’d written and then wrote it from scratch after I had finished The Sympathizer. Some of those ideas had filtered into the fiction—but all the work of the fiction worked itself into the writing of the nonfiction. The ambition in the back of my mind—I may not be there yet—is that I would love to be able to write fiction like criticism and criticism like fiction. I think of W.G. Sebald—a hero of mine—I can’t tell the difference in his work, whether it is fiction or nonfiction, it all feels like literature. So as I was writing these books closely together, I was doing the best to incorporate criticism into the fiction, and fiction into the criticism, so with The Sympathizer I was hoping to construct a narrator who could say dramatically very critical things, but who wouldn’t be restricted as an academic to source his beliefs. In Nothing Ever Dies, I couldn’t find a way to find a sense of humor into that book, but I really did try to take everything I had learned from the novel—narrative rhythm, for example—even working my basest unsaid feelings into the very shape of the thing. One of things I want both books to do is to move the reader both emotionally and intellectually.

Gấu biết đến Sebald là qua 1 bài viết của Sontag. Bà coi ông, 1 thứ nhà văn của nhà văn. Viet Thanh Nguyen coi ông là “hero” của mình, và rất mê lối viết trộn lẫn nhiều thể loại, phê bình, văn xuôi, hồi tưởng…. Gấu đọc Sebald khác hẳn, một kẻ săn hồn ma, như chính ông tự nhận, hay, với GCC, một lương tâm của nước Đức hậu chiến. Vả chăng tuy trộn lẫn nhiều thể loại, trong khi viết giả tưởng, nhưng với những bài viết đúng là phê bình, hay biên khảo, Sebald xuất hiện như 1 vị quan tòa, và văn của ông, là thứ phán đoán, truy xét, hỏi tội, Judgment.

TV giới thiệu bài viết mới có được, về ông, nhân mới xuống phố.

Trong bài viết, trong cuốn trên, tác giả nối kết Sebald, với vụ không kích, và với Thomas Bernhard.

Bài viết của Dyer về Sebald xoáy vào cuốn mà Gấu mê nhất của ông, Về lịch sử tự nhiên về huỷ diệt, “On the natural history of destruction”.

TV “phải” mua cuốn sách, để “phải” đi 1 đường về Sebald, là vì bài viết này, chưa kể bài viết về “Cuộc Tình Bỏ Đi” của Scott Fitzgerald, “Tender Is the Night” [cuốn “Một Chủ Nhật Khác” là cùng dòng với nó]

On the Natural History of Destruction goes to the epicenter of ruination, examining the Allied bombardment of German cities in the Second World War. Given the scale of the calamity, Sebald asks, why have German writers been so silent about it? How had it come about that 'the sense of unparalleled national humiliation felt by millions in the last years of the war had never really found verbal expression, and that those directly affected by the experience neither shared it with each other nor passed it on to the next generation'?

Geoff Dyer: W. G. Sebald, Bombing and Thomas Bernhard

Câu hỏi trên, 1 cách nào đó, có thể áp dụng vào Miền Bắc xứ Mít: Tại sao chúng vờ luôn Công Ơn Trời Biển của Thiên Triều?

Bài phỏng vấn W.G. Sebald do Eleanor

Wachtel thực hiện, Tin Văn quả có nhắc tới, qua cái tên là Kẻ săn hồn ma,

Ghost Hunter. Bài mới, chắc là bài cũ, nhưng thêm phần nhận xét của Wachtel.

Trò chuyện với W.G. Sebald: Bài này

trên The New Yorker online, Tin Văn có trích dịch, trong bài Tưởng niệm Sebald

Ghost Hunter

Eleanor Wachtel [CBC Radio’s

Writers & Company on April 18, 1998]:

Sebald viết một kinh cầu cho

một thế hệ, trong Di dân, The

Emigrants, một cuốn sách khác thường về hồi nhớ, lưu vong, và

chết chóc. Cách viết thì trữ tình, lyrical, giọng bi khúc, the mood elegiac.

Ðây là những câu chuyện về vắng mặt, dời đổi, bật rễ, mất mát, và tự

tử, người Ðức, người Do Thái, được viết bằng 1 cái giọng hết sức khơi

động, evocative, ám ảnh, haunting, và theo cách giảm bớt, understated

way. Di dân có thể gọi bằng

nhiều cái tên, một cuốn tiểu thuyết, một tứ khúc kể, a narrative quartet

[Chắc giống Tứ Khúc BHD

của GCC!], hay, giản dị, không thể gọi tên, sắp hạng. Ông diễn tả như

thế nào?

WG Sebald:

Nó là một hình thức của giả tưởng văn xuôi, a form of prose fiction. Theo tôi nghĩ, nó hiện hữu thường xuyên ở Ðại lục Âu châu hơn là ở thế giới Anglo-Saxon, đối thoại rất khó chui vào cái thứ giả tưởng văn xuôi này….

Nó là một hình thức của giả tưởng văn xuôi, a form of prose fiction. Theo tôi nghĩ, nó hiện hữu thường xuyên ở Ðại lục Âu châu hơn là ở thế giới Anglo-Saxon, đối thoại rất khó chui vào cái thứ giả tưởng văn xuôi này….

EW: Một nhà phê bình gọi

ông là kẻ săn hồn ma, a ghost hunter, ông có nghĩ về mình như thế?

WGS: Ðúng như thế. Yes,

I do. I think it’s pretty precise…

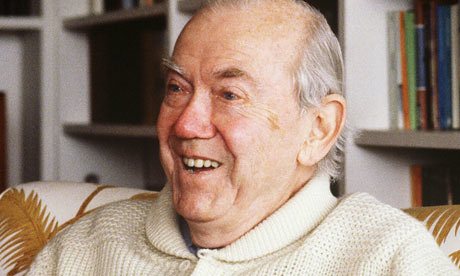

Thầy của Pico Iyer là Graham Greene.

Gấu mê Thầy, rồi tò mò đọc đệ tử của ông, và mê luôn!

Nhưng đọc Pico Iyer, thì quái làm sao, cứ nghĩ đến bạn Khờ của GCC!

Thầy dậy trò, chỉ có 1 đòn, làm thế nào "đi đâu loanh quanh":

How to move around the world

Bạn Khờ mà không thế sao?

Nhưng đọc Pico Iyer, thì quái làm sao, cứ nghĩ đến bạn Khờ của GCC!

Thầy dậy trò, chỉ có 1 đòn, làm thế nào "đi đâu loanh quanh":

How to move around the world

Bạn Khờ mà không thế sao?

Graham Greene in 1982: he taught Pico Iyer ‘how to move around the world’. Photograph: AFP

The Man Within My Head: Graham Greene, My Father and Me by Pico Iyer – review

Pico Iyer's meditation on the great influences of his life is a book that deserves to be loved

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/may/20/man-within-head-graham-greene-review

Graham Greene Dangerous Edge

http://www.tanvien.net/Tac_gia_ngoai/Pico_Iyer.html

Pico Iyer Commemorates the Centennial of Graham Greene's Birth Oct. 6, 2004

Pico Iyer tưởng niệm GG, nhân kỷ niệm 100 năm ngày sinh của sư phụ

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/feb/13/travel.features?INTCMP=SRCH

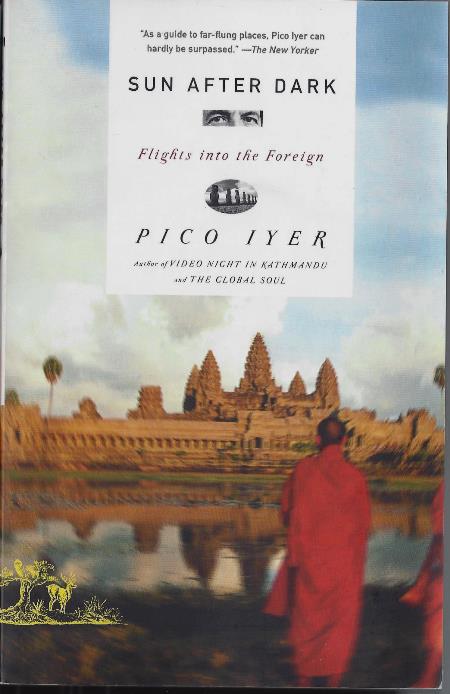

Iyer apparently reads like he travels, mixing often brilliant critical observation with autobiography, never travelling very far from himself. Some of the pieces describe these vicarious journeys, like that into the work of WG Sebald. Iyer's impression of the late German is that he was working to 'put us in the state he inhabits, unmoored, at a loss, in the dark'.

This reading crucially neglects, it seems to me, the great comedy of books like The Rings of Saturn; Sebald's everpresent sense of his chaotic, burdensome quests as morose caricatures of the human condition; his raised-eyebrow acknowledgment that the eternal seeker after truth is by his nature, at least, a somewhat ludicrous figure.

Though his own journeys don't have the historical heft of Sebald's, Iyer aspires to a similar psychological terrain. His clear eye for the ironies of contemporary global culture, for the Anglo-Indian heritage of Mumbai, the anachronistic tourist industry of Tibet, lead him always back, he says, to 'the questions I take everywhere with me, of possession ... of the play of light and dark ... and of what we take to be real'.

There are important questions, no doubt, but as he wanders with them in his head, the one sound Iyer seems never to hear is just the occasional snigger from around one of the world's four corners.

Note: Tờ Guardian đọc Sun After Dark, của Iyer, và so sánh với, của Sebald.