DC Memoriam

Một

trang Tạp Ghi của GCC, khi viết cho diễn đàn VHNT của PCL:

Rõ ràng là chẳng có gì là của Gấu cả. Vậy mà ông con trai DC, và có thể nói, gần như toàn bộ BBT, lẫn độc giả của nó, bực bội, không biết đoạn này của ông NQT, đoạn nào ông ta chôm: Đây là "xì tai" - từ của ông con DC - của ông ta!

Tuy nhiên, “vụ việc” làm PCL & NQT bực nhất, “có thể” là do cái thư ngỏ gửi Gunter Grass.

Thư, thoạt đầu do Gấu viết. Thời gian đó, Nguyễn Tiến Văn còn ở Toronto, anh đọc bản nháp, đề nghị, ông cho tôi góp phần, 1 phần vì tiếng Anh của anh vững hơn, 1 phần, anh cũng muốn đóng góp 1 vài ý. Thư viết xong, gửi PCL, đề nghị, nếu cần, sửa giùm câu cú, và vẫn nếu cần, cho ý kiến về nội dung.

Cả 1 đám xúm lại làm thịt lá thư. Viết nhu bố người ta. Phải năn nỉ, phải kể ra những nỗi thống khổ vì là nạn nhân của Vẹm, để được coi là tị nạn, phải...

Gấu điên lên, bèn gửi cho Phan Tấn Hải, Việt Báo. Anh nhờ Thân Trọng Mẫn gọi điện thoại cho những bằng hữu, và cái thư được đăng lần đầu tiên trên Việt Báo online. VHNT đăng sau chót, và cái danh sách của những viết của VHNT dược thêm vô, không có trong thư post lần đầu.Y Y chang tay Trần Đệ, Sếp mũi tẹt của Nguyễn Xuân Hoàng, khi nhận được lá thư Gấu gửi cho NXH, và anh phải xin ý kiến, hắn ta phán, chẳng có 1 lý do nào được nêu ra trong thư, mà Toà Án Đức chiếu theo đó, đồng ý cho tị nạn cả,

Lũ ngu này lầm lá thư ngỏ Gấu viết cho Grass, là lá đơn gửi cho Tòa Án Đức!

Rõ ràng là chẳng có gì là của Gấu cả. Vậy mà ông con trai DC, và có thể nói, gần như toàn bộ BBT, lẫn độc giả của nó, bực bội, không biết đoạn này của ông NQT, đoạn nào ông ta chôm: Đây là "xì tai" - từ của ông con DC - của ông ta!

Tuy nhiên, “vụ việc” làm PCL & NQT bực nhất, “có thể” là do cái thư ngỏ gửi Gunter Grass.

Thư, thoạt đầu do Gấu viết. Thời gian đó, Nguyễn Tiến Văn còn ở Toronto, anh đọc bản nháp, đề nghị, ông cho tôi góp phần, 1 phần vì tiếng Anh của anh vững hơn, 1 phần, anh cũng muốn đóng góp 1 vài ý. Thư viết xong, gửi PCL, đề nghị, nếu cần, sửa giùm câu cú, và vẫn nếu cần, cho ý kiến về nội dung.

Cả 1 đám xúm lại làm thịt lá thư. Viết nhu bố người ta. Phải năn nỉ, phải kể ra những nỗi thống khổ vì là nạn nhân của Vẹm, để được coi là tị nạn, phải...

Gấu điên lên, bèn gửi cho Phan Tấn Hải, Việt Báo. Anh nhờ Thân Trọng Mẫn gọi điện thoại cho những bằng hữu, và cái thư được đăng lần đầu tiên trên Việt Báo online. VHNT đăng sau chót, và cái danh sách của những viết của VHNT dược thêm vô, không có trong thư post lần đầu.Y Y chang tay Trần Đệ, Sếp mũi tẹt của Nguyễn Xuân Hoàng, khi nhận được lá thư Gấu gửi cho NXH, và anh phải xin ý kiến, hắn ta phán, chẳng có 1 lý do nào được nêu ra trong thư, mà Toà Án Đức chiếu theo đó, đồng ý cho tị nạn cả,

Lũ ngu này lầm lá thư ngỏ Gấu viết cho Grass, là lá đơn gửi cho Tòa Án Đức!

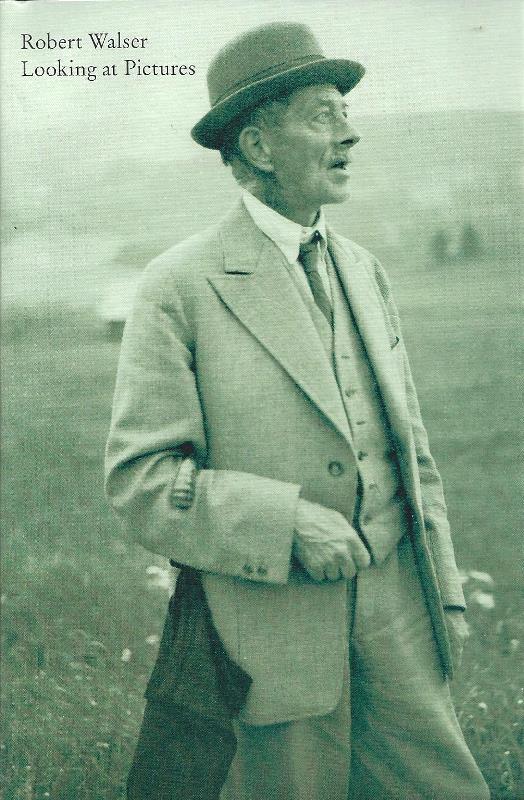

Tribute to Robert Walser

Vào lúc DC đi xa, là lúc Gấu đang mê Walser, bèn tưởng niệm DC, bằng cách đọc "Nhìn tranh" của Walser, lập lại kinh nghiệm hồi mới viết, mỗi lần thèm viết quá, thì bèn lôi Faulkner ra, thế nào cũng kiếm được một, hai câu làm mồi.

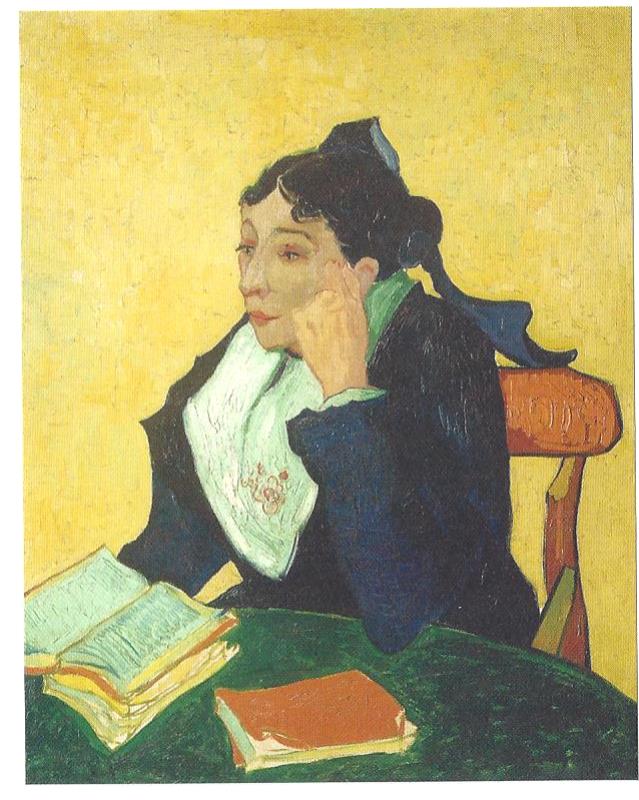

Vincent van Gogh, L'Arlesienne: Madame

Joseph-Michel Ginoux, 1888-89

"The

Van Gogh Picture"

"The Van Gogh Picture"

At an exhibition of paintings several years ago, I saw an, as it were, ravishing and priceless picture: Van Gogh's Arlesienne, the portrait of a peasant woman who is decidedly not pretty, as she is already rather old, sitting quietly in a chair and gazing pensively before her. She wears the sort of skirt one sees all the time, and has the sort of hands one encounters everywhere without paying them any attention, as they appear to be far from lovely. Nor can a modest ribbon in her hair count for much. The face of this woman is hard. Her features speak of a great many incursive experiences.

I willingly admit that at first I intended to devote only a moment's consideration to this picture-which to be sure struck me as a powerful work-since I wished to move on as quickly as possible to look at other items, but a strange something held me back, as if I'd been seized by the arm. Asking myself if there was anything at all of beauty to look upon here, I soon became convinced that one must pity the artist who had squandered such great industry on so low and charmless a subject. I asked myself: was this a picture I'd wish to own? But I didn't dare respond to this peculiar question with either a yes or no. I further submitted for my own contemplation the apparently simple and, it seemed to me, certainly not unjustified question of whether a suitable place even exists in our society for pictures like this Arlesienne. No one can possibly have commissioned such works; the artist would appear to have given himself the assignment and then painted something that perhaps no one ever wished to see depicted. Who could want to hang such an ordinary picture on his wall?

"Magnificent women," I said to myself, "were painted by Titian, Rubens and Lucas Cranach," and because I spoke these words, I am filled with pain, as it were, for our artist, who assuredly experienced a life more replete with suffering than joy, as well as for this age of ours, which is so difficult and dismal in many respects.

"To be sure," I continued, "the world is clearly often beautiful, and blithe hopes must ever blossom. But certain states of affairs are downright oppressive-no one would deny it."

Although something doleful or disturbing surrounded Van Gogh's picture, and all the harshest life circumstances seemed to emerge from beside or behind it-not quite sharply, but still recognizably enough-I nonetheless took pleasure in it, since the painting is a sort of masterpiece. The colors and brushwork possess the most extraordinary vitality, and formally the picture is outstanding. It contains, among other things, a wonderful patch of red that is delightfully in flux. Yet the work as a whole reflects more inner than outward beauty. Are not also certain books unlikely to become popular because they are not easily accessible, in other words because it is difficult to assign them a value? Sometimes things of beauty are inadequately perceived.

The effect the Van Gogh had on me was like that of a solemn tale. The woman suddenly began speaking about her life. Once she was a child and went to school. How beautiful it is to see one's parents every day, and to be initiated by teachers into all sorts of knowledge. How gay and bright the schoolroom and her interactions with her playmates. How sweet, how happy is youth!

These hard features were once soft, and these cold, almost malicious eyes were friendly and innocent. She was just as much and just as little as you. Just as rich in prospects and just as poor. A human being, like all of us, and her feet carried her through many a sunlit street as well as streets veiled in nocturnal darkness. She no doubt often went to church, or to dances. How often her hands must have opened a window, or pressed shut a door. These are the sorts of acts you and I perform daily, are they not, and in this circumstance resides a certain pettiness, but also grandeur. Can she not have had a lover, and known joy, and many sorrows? She listened to the ringing of bells, and with her eyes perceived the beauty of branches in blossom. Months and years passed for her, summer passed, winter. Is this not terribly simple. Her life was filled with toil. One day a painter said to her- himself just a poor working man-that he would like to paint her. She sits for him, calmly allowing him to paint her portrait. To him, she is not an indifferent model-for him, nothing and no one is indifferent. He paints her just as she is, plain and true. Without much intention, however, something great and noble enters into the simple picture, a solemnity of the soul it is impossible to overlook.

After I carefully impressed the picture upon my memory, I went home and wrote an essay about it for the magazine Kunst und Kiinstler. The content of this essay has now escaped me, for which reason the desire came over me to renew it, which has now been done.

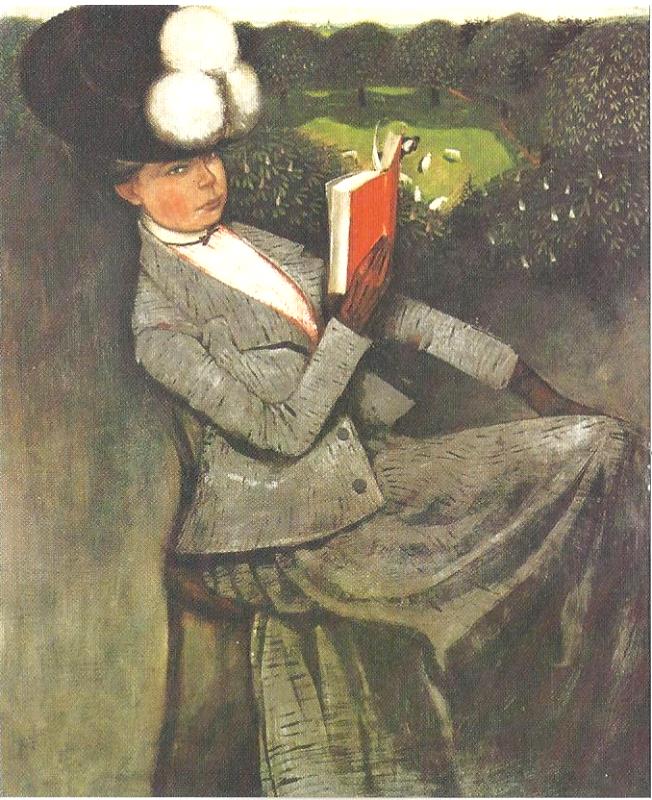

Karl Walser, Portrait of a Lady, 1902

A young lady, a girl of perhaps

twenty, is sitting in a chair and reading a book.

Or she has just been diligently reading, and now she is reflecting

on what she has read. This often happens, that someone who

is reading must pause, because all sorts of ideas having to

do with the book keenly engage him. The reader is dreaming;

perhaps she is comparing the subject matter of the book to her

own experiences hitherto; she is thinking about the hero of

the book, while she fancies herself almost its heroine. But now

to the picture, to the way it is painted. The picture is strange,

and the painting in it is delicate and subtle, because the painter,

in a mood of beautiful audacity, has crossed the boundaries of

the usual and has thrust his way through a biased reality out to

freedom. In painting the portrait of the young lady, he is also painting

her amiable secret reveries, her thoughts and daydreams, her lovely,

happy imagination, since, directly above the reader's head, or brain,

in a softer, more delicate distance, as though it were the construction

of a fantasy, he has painted a green meadow surrounded by a ring of

sumptuous chestnut trees and on this meadow, in sweet, sunlit peace,

a shepherd lies sprawled, he too appearing to read a book since he

has nothing else to do. The shepherd is wearing a dark blue jacket,

and around this contented loafer graze the lambs and the sheep, while

overhead in the summer morning air, swallows fly across the cloudless

sky. Looming up from the opulent, rounded tops of the leafy trees, one

can glimpse the wispy tips of a few firs. The green of the meadow is rich

and warm, and speaks a romantic and adventurous language, and the whole

cloudless picture inspires observant, quiet contemplation. The shepherd

off in the distance on his painted green meadow is undoubtedly happy.

Will the girl who is reading the book also be happy? She certainly would

deserve to be.

Every creature and every living thing in the world should be happy. No one should be unhappy.

Translated by Lydia Davis

Every creature and every living thing in the world should be happy. No one should be unhappy.

Translated by Lydia Davis

This painting portrays something like a moral dilapidation.

But are not loosenings of moral strictures at times elegant?

This category includes women who are, to begin with, beautiful, and secondarily straying, etc., from the proper path.

A variety of straying would seem to be the subject of the picture I am observing here, which appears to have been painted with exceptional delicacy, caution, precision, intelligence and melodiousness.

from "A Discussion of a Picture"

Looking at Pictures presents a little-known facet of the work of the eccentric Swiss genius Robert Walser (1878-1956): his writings on art.

Translated by Susan Bernofsky, Lydia Davis, and Christopher Middleton.

[Lời giới thiệu bìa sau]

Note: Loạt bài "Nhìn Tranh" này, Tin Văn giới thiệu, tưởng niệm Walser, và còn là 1 cách ăn theo, tiễn DC, vì do mù tịt về hội họa, bèn mượn hoa tiến Phật, thay vì viết nhảm, làm thơ nhảm tưởng niệm DC!

Comments

Post a Comment