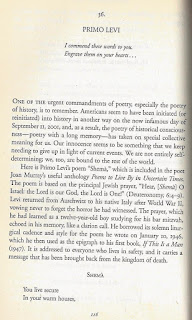

Primo Levi

PRIMO LEVI

I commend these words to you.

Engrave them on your hearts...

ONE OF THE

urgent commandments of poetry, especially the poetry of history, is to

remember. Americans seem to have been initiated (or re initiated) into history

in another way on the now infamous day of September 11, 2001, and, as a result,

the poetry of historical consciousness-poetry with a long memory-has taken on

special collective meaning for us. Our innocence seems to be something that we

keep needing to give up in light of current events. We are not entirely self-determining;

we, too, are bound to the rest of the world.

Here is

Primo Levi's poem "Shemà" which is included in the poet Joan

Murray's useful anthology Poems to Live

By in Uncertain Times. The poem is based on the principal Jewish prayer,

"Hear, [Shemà] O Israel: the

Lord is our God, the Lord is One!" (Deuteronomy, 6:4-9).

Levi

returned from Auschwitz to his native Italy after World War II, vowing never to

forget the horror he had witnessed. The prayer, which he had learned as a

twelve-year-old boy studying for his bar mitzvah, echoed in his memory, like a

clarion call. He borrowed its solemn liturgical cadence and style for the poem

he wrote on January 10, 1946, which he then used as the epigraph to his first

book, If This Is a Man (1947). It is

addressed to everyone who lives in safety, and it carries a message that has

been brought back from the kingdom of death.

SHEMÀ

You live

secure

In your warm

houses,

Who return

at evening to find

Hot food and

friendly faces:

Consider whether this is a man,

Who labors in the mud

Who knows no peace

Who fights for a crust of bread

Who dies at a yes or a no.

Consider whether this is a woman,

Without hair or name

With no more strength to remember

Eyes empty and womb cold

As a frog in winter.

Consider

that this has been:

I commend

these words to you.

Engrave them

on your hearts

When you are

in your house, when you walk on your way,

When you go

to bed, when you rise.

Repeat them

to your children.

Or may your

house crumble,

Disease

render you powerless,

Your

offspring avert their faces from you.

(TRANSLATED BY RUTH FELDMAN AND BRIAN

SWANN)

In this

poem, Levi was especially drawing on verses six and seven of Deuteronomy:

And these

words, which I command thee this day, shall be in thine heart: And thou shalt

teach them diligently unto thy children, and thou shalt talk of them when thou

sittest in thine house, and when thou walkest by the way, and when thou liest down,

and when thou risest up.

"Whether we like it or not," Levi wrote to a

friend, "we are witnesses and we carry the weight of that fact." The

burden of memory is heavy, but also electrifying. "I had a torrent of

urgent things I had to tell the civilized world," he declared. "I

felt the tattooed number on my arm burning like a sore."

The prophetic fury behind the particular witnessing, the

remembering, at the end of Levi's poem is immense, The poet puts a terrible curse

upon anyone who forgets these people, this Adam and Eve, who - have been so

dehumanized that we are asked to consider "if this is a man" and

"if this is a woman." It is a lasting obligation to remember their

suffering. It is a human injunction, a ritual commandment. We must do

everything in our powers, Levi suggests, to keep them from becoming anonymous

victims; 'Ye must engrave their images on our hearts and pass on their memories

to our children.

Edward Hirsch: Poet's Choice

Comments

Post a Comment