Hai Cu

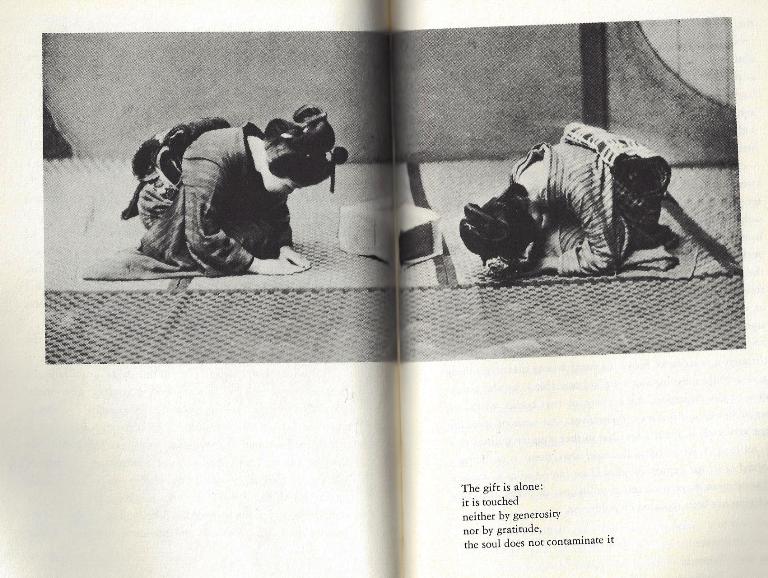

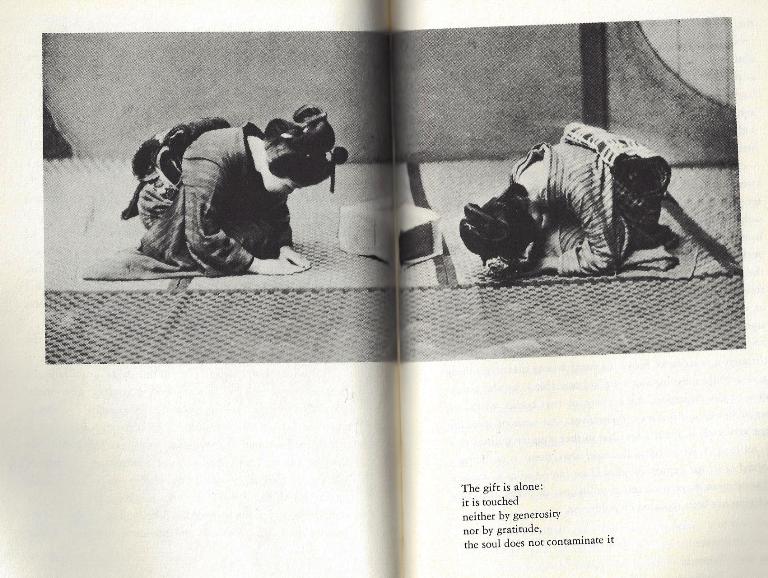

Gói quà thì

mình ên

“Đại lượng” đếch đụng được vô nó

“Biết ơn” cái con mẹ gì lại càng không

Cái gọi là linh hồn không làm nhiễm nó.

“Đại lượng” đếch đụng được vô nó

“Biết ơn” cái con mẹ gì lại càng không

Cái gọi là linh hồn không làm nhiễm nó.

So

The haiku's

task is to achieve exemption from meaning within a perfectly readerly

discourse

(a contradiction denied to Western art, which can contest meaning only

by

rendering its discourse incomprehensible), so that to our eyes the

haiku is

neither eccentric nor familiar: it resembles nothing at all: readerly,

it seems

to us simple, close, known, delectable, delicate, "poetic"-in a word,

offered to a whole range of reassuring predicates; insignificant

nonetheless,

it resists us, finally loses the adjectives which a moment before we

had

bestowed upon it, and enters into that suspension of meaning which to

us is the

strangest thing of all, since it makes impossible the most ordinary

exercise of

our language, which is commentary. What are we to say of this:

Spring

breeze:

The boatman chews his grass stem.

The boatman chews his grass stem.

or this:

Full moon

And on the matting

The shadow of a pine tree.

And on the matting

The shadow of a pine tree.

or of this:

In the

fisherman's house

The smell of dried fish

And heat.

The smell of dried fish

And heat.

or again

(but not finally, for the examples are countless) of this:

The winter

wind blows.

The cats' eyes

Blink.

The cats' eyes

Blink.

Such traces (the word suits the haiku,

a kind of faint gash

inscribed upon time) establish

what we have been able to call "the vision without commentary." This

vision (the word is still too Western) is in fact entirely privative;

what is

abolished is not meaning but any notion of finality: the haiku serves

none of

the purposes (though they themselves are quite gratuitous) conceded to

literature: insignificant (by a technique of meaning-arrest), how could

it

instruct, express, divert? In the same way, whereas certain Zen schools

conceive

of seated meditation as a practice intended for the obtaining of

Buddha-hood,

others reject even this (apparently essential) finality: one must

remain seated "just to remain

seated."

Is not the haiku (like the countless graphic

gestures which mark modern and social Japanese life) also written "just to write"?

What disappears in the haiku are the two basic functions of our (age-old) classical writing: on the one hand, description (the boatman's grass stem, the pine tree's shadow, the smell of fish, the winter wind are not described, i.e., embellished with significations, with moralities, committed as indices to the revelation of a truth or of a sentiment: meaning is denied to reality; furthermore, reality no longer commands even the meaning of reality); and on the other, definition; not only is definition transferred to gesture, if only a graphic gesture, but it is also shunted toward a kind of inessential-eccentric-efflorescence of the object, as one Zen anecdote puts it nicely, in which the master awards the prize for definition (what is a fan?) not even to the silent, purely gestural illustration of function (to wave the fan), but to the invention of a chain of aberrant actions (to close the fan and scratch one's neck with it, to reopen it, put a cookie on it and offer it to the master). Neither describing nor defining, the haiku (as I shall finally name any discontinuous feature, any event of Japanese life as it offers itself to my reading), the haiku diminishes to the point of pure and sole designation. It's that, it's thus, says the haiku, it's so. Or better still: so! it says, with a touch so instantaneous and so brief (without vibration or recurrence) that even the copula would seem excessive, a kind of remorse for a forbidden, permanently alienated definition. Here meaning is only a flash, a slash of light: When the light of sense goes out, but with a flash that has revealed the invisible world, Shakespeare wrote; but the haiku's flash illumines, reveals nothing; it is the flash of a photograph one takes very carefully (in the Japanese manner) but having neglected to load the camera with film. Or again: haiku reproduces the designating gesture of the child pointing at whatever it is (the haiku shows no partiality for the subject), merely saying: that! with a movement so immediate (so stripped of any mediation: that of knowledge, of nomination, or even of possession) that what is designated is the very inanity of any classification of the object: nothing special, says the haiku, in accordance with the spirit of Zen: the event is not namable according to any species, its specialty short circuits: like a decorative loop, the haiku coils back on itself, the wake of the sign which seems to have been traced is erased: nothing has been acquired, the word's stone has been cast for nothing: neither waves nor flow of meaning.

What disappears in the haiku are the two basic functions of our (age-old) classical writing: on the one hand, description (the boatman's grass stem, the pine tree's shadow, the smell of fish, the winter wind are not described, i.e., embellished with significations, with moralities, committed as indices to the revelation of a truth or of a sentiment: meaning is denied to reality; furthermore, reality no longer commands even the meaning of reality); and on the other, definition; not only is definition transferred to gesture, if only a graphic gesture, but it is also shunted toward a kind of inessential-eccentric-efflorescence of the object, as one Zen anecdote puts it nicely, in which the master awards the prize for definition (what is a fan?) not even to the silent, purely gestural illustration of function (to wave the fan), but to the invention of a chain of aberrant actions (to close the fan and scratch one's neck with it, to reopen it, put a cookie on it and offer it to the master). Neither describing nor defining, the haiku (as I shall finally name any discontinuous feature, any event of Japanese life as it offers itself to my reading), the haiku diminishes to the point of pure and sole designation. It's that, it's thus, says the haiku, it's so. Or better still: so! it says, with a touch so instantaneous and so brief (without vibration or recurrence) that even the copula would seem excessive, a kind of remorse for a forbidden, permanently alienated definition. Here meaning is only a flash, a slash of light: When the light of sense goes out, but with a flash that has revealed the invisible world, Shakespeare wrote; but the haiku's flash illumines, reveals nothing; it is the flash of a photograph one takes very carefully (in the Japanese manner) but having neglected to load the camera with film. Or again: haiku reproduces the designating gesture of the child pointing at whatever it is (the haiku shows no partiality for the subject), merely saying: that! with a movement so immediate (so stripped of any mediation: that of knowledge, of nomination, or even of possession) that what is designated is the very inanity of any classification of the object: nothing special, says the haiku, in accordance with the spirit of Zen: the event is not namable according to any species, its specialty short circuits: like a decorative loop, the haiku coils back on itself, the wake of the sign which seems to have been traced is erased: nothing has been acquired, the word's stone has been cast for nothing: neither waves nor flow of meaning.

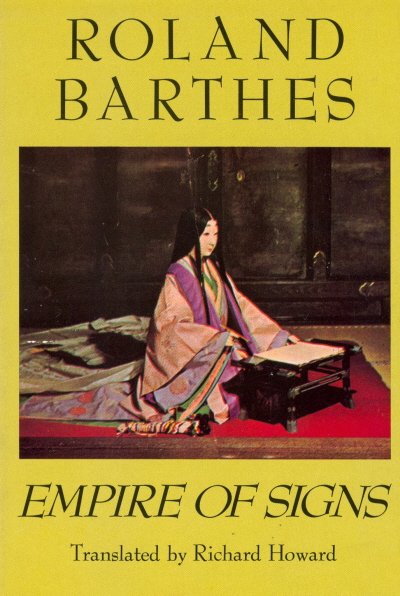

Roland

Barthes: Empire of Signs

[Translated by Richard Howard]

[Translated by Richard Howard]

Bài tuy ngắn,

nhưng thật khó dịch, và thật là tuyệt vời về Hai Cu. GCC đọc, cũng lâu

rồi, hăm

he dịch hoài, nhưng thấy căng quá. Khó, 1 phần phải biết 1 tí về ký

hiệu, theo

kiểu của Barthes, và môn "ký hiệu học" mà ông có thể được coi là một

trong những người sáng lập.

Mở ra 1 phát, là Barthes đã phán, Đông là Đông, Tây là Tây rồi. Một bên, thì cố lấy hết mẹ cái nghĩa ra khỏi bản văn, một bên thì cố làm cho nó rối tung lên, đếch làm sao đọc được nữa, the haiku's task is to achieve exemption from meaning within a perfectly readerly discourse (a contradiction denied to Western art, which can contest meaning only by rendering its discourse incomprehensible),

Mở ra 1 phát, là Barthes đã phán, Đông là Đông, Tây là Tây rồi. Một bên, thì cố lấy hết mẹ cái nghĩa ra khỏi bản văn, một bên thì cố làm cho nó rối tung lên, đếch làm sao đọc được nữa, the haiku's task is to achieve exemption from meaning within a perfectly readerly discourse (a contradiction denied to Western art, which can contest meaning only by rendering its discourse incomprehensible),

Khúc tiếng

Tây, là từ bài “avant-propos” của Roger Munier, người biên tập &

chuyển qua

tiếng Tẩy những bài Hai Cu do ông tuyển chọn. Bài Hai Cu, trong yếu

tính của nó,

thì quá cả 1 bài thơ, cả theo cái nghĩa cực mạnh mà người ta đem đến

cho từ này.

So với những nghệ thuật khác ở Nhựt, như tuồng Nô, bắn cung, vẽ chữ,

tranh họa,

nghệ thuật cắm hoa, nghệ thuật làm vườn, tất cả đều thấm đẫm cái gọi là

Thiền.

Cái thực tập, cái/cách viết/đọc của nó thì trong chính nó, là một bài

tập tinh

thần/ linh thần. Chẳng có khiên cưỡng khi phán, cái mà Hai Cu hoàn tất

đề nghị,

là 1 kinh nghiệm đồng nhất với cái gọi là satori,

về mặc khải, đốn ngộ, [tâm hồn] sáng chưng lên.

Đế Quốc

Ký Hiệu,

tên của

Barthes phịa ra, để chỉ Đế Quốc Mặt Trời, nhưng với ông, đế quốc “của”

ký hiệu,

trong những ký hiệu của nó, có thơ Hai Cu. Bài viết về Hai Cu tuyệt

lắm, TV sẽ

đi liền, cũng 1 cách để thêm 1 tiếng nói của hải ngoại cho tuyệt tác về

thơ Hai

Cu của 1 đấng ở trong nước!

Bài Haiku sau đây, của Basho, ở trang bìa sau, của cuốn anthologie mà chẳng thú sao:

Bài Haiku sau đây, của Basho, ở trang bìa sau, của cuốn anthologie mà chẳng thú sao:

“Lâu lâu, mây, bèn thương

hại, ngưng một phát, cho người ngắm trăng.”

“De temps à

autre

Les nuages accordent une pause

À ceux qui contemplent la lune.”

Les nuages accordent une pause

À ceux qui contemplent la lune.”

Câu tiếng Mít, "phóng

bút",

từ "accorder", cho thấy, dịch

thơ khó vô cùng, và càng khó càng cần dịch

-Edmund White

The New York Times Book Review

Nếu không có Nhật Bản, thì Barthes sẽ phịa ra nó. Nhưng nước Nhật ở trong Đế Quốc Ký Hiệu cũng không thực, như Barthes cẩn trọng nói với chúng ta là, ông không nghiên cứu nước Nhật thực, mà là một nước Nhựt của riêng ông, do ông ‘chế’ ra. Trong cái nước Nhựt giả tưởng này, thì không hề có cái "bên trong" khủng khiếp như là ở Tây phương. Không linh hồn, tâm hồn, không Thượng Đế, không số mệnh, không cái tôi, không vinh quang, không đỉnh cao, không siêu hình, không “cơn sốt lên lương, lên chức, vô Đảng, vô BCT” và sau cùng, không có cái gọi là ý nghĩa.

Với Barthes, Nhật Bản là một thí nghiệm, một thách đố để suy nghĩ về cái không thể suy nghĩ, một nơi chốn mà ý nghĩa thì sau cùng bị loại trừ. Thiên đường, thực sự là vậy, cho một tay sinh viên lớn, về ký hiệu.

Gói quà thì

mình ên

“Đại lượng” đếch đụng được vô nó

“Biết ơn” cái con mẹ gì lại càng không

Cái gọi là linh hồn không làm nhiễm nó.

“Đại lượng” đếch đụng được vô nó

“Biết ơn” cái con mẹ gì lại càng không

Cái gọi là linh hồn không làm nhiễm nó.

So

The haiku's

task is to achieve exemption from meaning within a perfectly readerly

discourse

(a contradiction denied to Western art, which can contest meaning only

by

rendering its discourse incomprehensible), so that to our eyes the

haiku is

neither eccentric nor familiar: it resembles nothing at all: readerly,

it seems

to us simple, close, known, delectable, delicate, "poetic"-in a word,

offered to a whole range of reassuring predicates; insignificant

nonetheless,

it resists us, finally loses the adjectives which a moment before we

had

bestowed upon it, and enters into that suspension of meaning which to

us is the

strangest thing of all, since it makes impossible the most ordinary

exercise of

our language, which is commentary. What are we to say of this:

Spring

breeze:

The boatman chews his grass stem.

The boatman chews his grass stem.

or this:

Full moon

And on the matting

The shadow of a pine tree.

And on the matting

The shadow of a pine tree.

or of this:

In the

fisherman's house

The smell of dried fish

And heat.

The smell of dried fish

And heat.

or again

(but not finally, for the examples are countless) of this:

The winter

wind blows.

The cats' eyes

Blink.

The cats' eyes

Blink.

Such traces (the word suits the haiku,

a kind of faint gash

inscribed upon time) establish

what we have been able to call "the vision without commentary." This

vision (the word is still too Western) is in fact entirely privative;

what is

abolished is not meaning but any notion of finality: the haiku serves

none of

the purposes (though they themselves are quite gratuitous) conceded to

literature: insignificant (by a technique of meaning-arrest), how could

it

instruct, express, divert? In the same way, whereas certain Zen schools

conceive

of seated meditation as a practice intended for the obtaining of

Buddha-hood,

others reject even this (apparently essential) finality: one must

remain seated "just to remain

seated."

Is not the haiku (like the countless graphic

gestures which mark modern and social Japanese life) also written "just to write"?

What disappears in the haiku are the two basic functions of our (age-old) classical writing: on the one hand, description (the boatman's grass stem, the pine tree's shadow, the smell of fish, the winter wind are not described, i.e., embellished with significations, with moralities, committed as indices to the revelation of a truth or of a sentiment: meaning is denied to reality; furthermore, reality no longer commands even the meaning of reality); and on the other, definition; not only is definition transferred to gesture, if only a graphic gesture, but it is also shunted toward a kind of inessential-eccentric-efflorescence of the object, as one Zen anecdote puts it nicely, in which the master awards the prize for definition (what is a fan?) not even to the silent, purely gestural illustration of function (to wave the fan), but to the invention of a chain of aberrant actions (to close the fan and scratch one's neck with it, to reopen it, put a cookie on it and offer it to the master). Neither describing nor defining, the haiku (as I shall finally name any discontinuous feature, any event of Japanese life as it offers itself to my reading), the haiku diminishes to the point of pure and sole designation. It's that, it's thus, says the haiku, it's so. Or better still: so! it says, with a touch so instantaneous and so brief (without vibration or recurrence) that even the copula would seem excessive, a kind of remorse for a forbidden, permanently alienated definition. Here meaning is only a flash, a slash of light: When the light of sense goes out, but with a flash that has revealed the invisible world, Shakespeare wrote; but the haiku's flash illumines, reveals nothing; it is the flash of a photograph one takes very carefully (in the Japanese manner) but having neglected to load the camera with film. Or again: haiku reproduces the designating gesture of the child pointing at whatever it is (the haiku shows no partiality for the subject), merely saying: that! with a movement so immediate (so stripped of any mediation: that of knowledge, of nomination, or even of possession) that what is designated is the very inanity of any classification of the object: nothing special, says the haiku, in accordance with the spirit of Zen: the event is not namable according to any species, its specialty short circuits: like a decorative loop, the haiku coils back on itself, the wake of the sign which seems to have been traced is erased: nothing has been acquired, the word's stone has been cast for nothing: neither waves nor flow of meaning.

What disappears in the haiku are the two basic functions of our (age-old) classical writing: on the one hand, description (the boatman's grass stem, the pine tree's shadow, the smell of fish, the winter wind are not described, i.e., embellished with significations, with moralities, committed as indices to the revelation of a truth or of a sentiment: meaning is denied to reality; furthermore, reality no longer commands even the meaning of reality); and on the other, definition; not only is definition transferred to gesture, if only a graphic gesture, but it is also shunted toward a kind of inessential-eccentric-efflorescence of the object, as one Zen anecdote puts it nicely, in which the master awards the prize for definition (what is a fan?) not even to the silent, purely gestural illustration of function (to wave the fan), but to the invention of a chain of aberrant actions (to close the fan and scratch one's neck with it, to reopen it, put a cookie on it and offer it to the master). Neither describing nor defining, the haiku (as I shall finally name any discontinuous feature, any event of Japanese life as it offers itself to my reading), the haiku diminishes to the point of pure and sole designation. It's that, it's thus, says the haiku, it's so. Or better still: so! it says, with a touch so instantaneous and so brief (without vibration or recurrence) that even the copula would seem excessive, a kind of remorse for a forbidden, permanently alienated definition. Here meaning is only a flash, a slash of light: When the light of sense goes out, but with a flash that has revealed the invisible world, Shakespeare wrote; but the haiku's flash illumines, reveals nothing; it is the flash of a photograph one takes very carefully (in the Japanese manner) but having neglected to load the camera with film. Or again: haiku reproduces the designating gesture of the child pointing at whatever it is (the haiku shows no partiality for the subject), merely saying: that! with a movement so immediate (so stripped of any mediation: that of knowledge, of nomination, or even of possession) that what is designated is the very inanity of any classification of the object: nothing special, says the haiku, in accordance with the spirit of Zen: the event is not namable according to any species, its specialty short circuits: like a decorative loop, the haiku coils back on itself, the wake of the sign which seems to have been traced is erased: nothing has been acquired, the word's stone has been cast for nothing: neither waves nor flow of meaning.

Roland

Barthes: Empire of Signs

[Translated by Richard Howard]

[Translated by Richard Howard]

Bài tuy ngắn,

nhưng thật khó dịch, và thật là tuyệt vời về Hai Cu. GCC đọc, cũng lâu

rồi, hăm

he dịch hoài, nhưng thấy căng quá. Khó, 1 phần phải biết 1 tí về ký

hiệu, theo

kiểu của Barthes, và môn "ký hiệu học" mà ông có thể được coi là một

trong những người sáng lập.

Mở ra 1 phát, là Barthes đã phán, Đông là Đông, Tây là Tây rồi. Một bên, thì cố lấy hết mẹ cái nghĩa ra khỏi bản văn, một bên thì cố làm cho nó rối tung lên, đếch làm sao đọc được nữa, the haiku's task is to achieve exemption from meaning within a perfectly readerly discourse (a contradiction denied to Western art, which can contest meaning only by rendering its discourse incomprehensible),

Mở ra 1 phát, là Barthes đã phán, Đông là Đông, Tây là Tây rồi. Một bên, thì cố lấy hết mẹ cái nghĩa ra khỏi bản văn, một bên thì cố làm cho nó rối tung lên, đếch làm sao đọc được nữa, the haiku's task is to achieve exemption from meaning within a perfectly readerly discourse (a contradiction denied to Western art, which can contest meaning only by rendering its discourse incomprehensible),

Thái Bá Tân bị phát hiện dịch sai 'Thơ Haiku Nhật Bản'

Cách

dịch sai hoặc chuyển ngữ thô vụng của Thái Bá Tân khiến rất nhiều bài

thơ của Basho, Chiyo… trong ấn phẩm dày 600 trang bị phá hỏng.

Comments

Post a Comment