Vie et Destin

Tuyệt tác thế giới

[Bard: In medieval Gaelic and British culture, a bard was a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or noble), to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise the patron's own activities. Net]

Như "Đời và Số Mệnh", bản dịch mới của “Stalingrad” là 1 tuyệt tác.

Khói và Bụi

Vasily Grossman, vị “bard” vĩ đại nhất của Đệ Nhị Thế Chiến

[Bard: In medieval Gaelic and British culture, a bard was a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or noble), to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise the patron's own activities. Net]

Như "Đời và Số Mệnh", bản dịch mới của “Stalingrad” là 1 tuyệt tác.

****

Vào những năm cuối của cuộc đời của mình, Vasily Grossman gìn giữ một

số những lưu niệm trân quí trong căn hộ tiều tụy ở Moscow. Một trong số

đó, là 1 cây đèn bảo hộ, từ đồng nghiệp hầm mỏ ở Donbas, nơi là 1 nhà

hoá học trẻ, ông đã làm công việc phòng ngừa những vụ nổ hầm. Một kỷ vật

khác, là cuốn sổ tay mà ông kiếm thấy, sau khi thoát khỏi lò thiêu

Treblinka.

Sinh năm 1905, trong 1 gia đình Do Thái ở Berdichev, bây giờ là ở Ukraine, Grossman, đã vô trại tù sau khi mệt mỏi rã rời vì những công việc của ông, như là 1 phóng viên tiền tuyến Xô Viết cho nhật báo của Hồng Quân Liên Xô. Vào tháng 11 năm 1944, ông cho in, trên tờ Znamya, tiểu luận “Địa Ngục Treblinka”. Nó được coi như - không chỉ 1 trong những chứng tích thứ nhất trong những ghi nhận về Lò Thiêu, như ghi nhận của Alexandra Popoff trong cuốn tiểu sử thận trọng nhưng quyến rũ của bà - một tác phẩm “nghệ thuật, thứ thiệt, bất diệt, đời đời”

Trong 1 bài viết, năm 1946, Grossman khẳng định: “Không có gì quí báu hơn là đời người. Cái sự mất mát, tổn thất của nó thì là… chấm hết, và không thể nào thay thế được”. Cây đèn của người thợ mỏ, cuốn sổ tay của 1 đứa bé, xác minh niềm tin xương tuỷ đó. Tuy nhiên, là 1 ký giả tối hảo, và sau đó, 1 tiểu thuyết gia không có 1 người thứ hai, về những điều ghê rợn của chiến tranh, của độc tài, số phận của ông là để sống, cư ngụ, ở những thời kỳ và những nơi chốn mà hàng triệu triệu con người cắm rễ. Trong cuốn “Stalingrad”, vừa mới có bản tiếng Anh, cái nhìn của 1 bà già đang hấp hối con phố bị bom đạn, bật ra câu hỏi nhức nhối: “Nỗi khổ đau của con người. Liệu nó sẽ được tưởng nhớ trong hàng hàng thế kỷ sẽ tới”? Hay những giọt nước mắt và khổ đau sẽ biến mất như “khói và bụi theo gió bay đi”. Tác phẩm của Grossman, chứa trong nó giả tưởng lớn lao nhất của Đệ Nhị Chiến trong bất cứ 1 ngôn ngữ nào, sẽ bảo tồn được nỗi khổ đau của con người, thoát ra khỏi niềm quên lãng .

Độc giả Tây Phương phần lớn biết Grossman qua cuốn “Đời và Số”, cuốn sử thi của ông về trận đánh Leningrad, và cái tiếp sau của nó. Sau khi được hoàn tất vào năm 1960, KGB tịch thu bản thảo. Kiểm duyệt Xô Viết phán, những so sánh “vô tư” – thản nhiên, không do dự - giữa những dã man của chế độ Nazi và “Xì ta lin nít” sẽ làm cho nó không được xb trong vòng 250 năm. Sự quan tâm thận trọng của tác giả cuốn sách về tinh thần bài - Do Thái thấm đậm cả hai chế độ sẽ làm nhức nhối đám quan chức Liên Xô nhiều thập kỷ.

Grossman chết, trong nghèo khổ và vẫn trong nghi kỵ soi mói, vào năm 1964. Nhưng vào năm 1980, “Đời và Số” tới được Tây Phương và qua dạng vi phim. Đài và chuyển thể trình diễn tưng bừng, và được coi là “Chiến Tranh và Hòa Bình” của thế kỷ 20.

Sự song song với Tolstoy - vị sư phụ, vừa chúc phúc vừa gây họa cho đệ tử Grossman - được nhìn ra, ngay từ thập niên 1940. Xì, chính ông ta, như Ms Popoff cho biết, đã “nhập thân”, “anticipated” – theo nghĩa “dựng dậy cái thây ma là chế độ Ngụy”, thí dụ - một Chiến Tranh và Hòa Bình “Xô Viết” – theo kiểu Tô Thuỳ Yên là “nhà văn Việt” của Đặng Tiến, chính xừ luỷ, vưỡn thí dụ: Grossman, có 1 thời được coi là đê tử ruột của Maxim Gorky, có vẻ như là ứng viên số 1, để viết nó.

Sinh năm 1905, trong 1 gia đình Do Thái ở Berdichev, bây giờ là ở Ukraine, Grossman, đã vô trại tù sau khi mệt mỏi rã rời vì những công việc của ông, như là 1 phóng viên tiền tuyến Xô Viết cho nhật báo của Hồng Quân Liên Xô. Vào tháng 11 năm 1944, ông cho in, trên tờ Znamya, tiểu luận “Địa Ngục Treblinka”. Nó được coi như - không chỉ 1 trong những chứng tích thứ nhất trong những ghi nhận về Lò Thiêu, như ghi nhận của Alexandra Popoff trong cuốn tiểu sử thận trọng nhưng quyến rũ của bà - một tác phẩm “nghệ thuật, thứ thiệt, bất diệt, đời đời”

Trong 1 bài viết, năm 1946, Grossman khẳng định: “Không có gì quí báu hơn là đời người. Cái sự mất mát, tổn thất của nó thì là… chấm hết, và không thể nào thay thế được”. Cây đèn của người thợ mỏ, cuốn sổ tay của 1 đứa bé, xác minh niềm tin xương tuỷ đó. Tuy nhiên, là 1 ký giả tối hảo, và sau đó, 1 tiểu thuyết gia không có 1 người thứ hai, về những điều ghê rợn của chiến tranh, của độc tài, số phận của ông là để sống, cư ngụ, ở những thời kỳ và những nơi chốn mà hàng triệu triệu con người cắm rễ. Trong cuốn “Stalingrad”, vừa mới có bản tiếng Anh, cái nhìn của 1 bà già đang hấp hối con phố bị bom đạn, bật ra câu hỏi nhức nhối: “Nỗi khổ đau của con người. Liệu nó sẽ được tưởng nhớ trong hàng hàng thế kỷ sẽ tới”? Hay những giọt nước mắt và khổ đau sẽ biến mất như “khói và bụi theo gió bay đi”. Tác phẩm của Grossman, chứa trong nó giả tưởng lớn lao nhất của Đệ Nhị Chiến trong bất cứ 1 ngôn ngữ nào, sẽ bảo tồn được nỗi khổ đau của con người, thoát ra khỏi niềm quên lãng .

Độc giả Tây Phương phần lớn biết Grossman qua cuốn “Đời và Số”, cuốn sử thi của ông về trận đánh Leningrad, và cái tiếp sau của nó. Sau khi được hoàn tất vào năm 1960, KGB tịch thu bản thảo. Kiểm duyệt Xô Viết phán, những so sánh “vô tư” – thản nhiên, không do dự - giữa những dã man của chế độ Nazi và “Xì ta lin nít” sẽ làm cho nó không được xb trong vòng 250 năm. Sự quan tâm thận trọng của tác giả cuốn sách về tinh thần bài - Do Thái thấm đậm cả hai chế độ sẽ làm nhức nhối đám quan chức Liên Xô nhiều thập kỷ.

Grossman chết, trong nghèo khổ và vẫn trong nghi kỵ soi mói, vào năm 1964. Nhưng vào năm 1980, “Đời và Số” tới được Tây Phương và qua dạng vi phim. Đài và chuyển thể trình diễn tưng bừng, và được coi là “Chiến Tranh và Hòa Bình” của thế kỷ 20.

Sự song song với Tolstoy - vị sư phụ, vừa chúc phúc vừa gây họa cho đệ tử Grossman - được nhìn ra, ngay từ thập niên 1940. Xì, chính ông ta, như Ms Popoff cho biết, đã “nhập thân”, “anticipated” – theo nghĩa “dựng dậy cái thây ma là chế độ Ngụy”, thí dụ - một Chiến Tranh và Hòa Bình “Xô Viết” – theo kiểu Tô Thuỳ Yên là “nhà văn Việt” của Đặng Tiến, chính xừ luỷ, vưỡn thí dụ: Grossman, có 1 thời được coi là đê tử ruột của Maxim Gorky, có vẻ như là ứng viên số 1, để viết nó.

Sự thực, cùng với “Đời và Số”,

“Stalingrad” tạo nên “bộ đôi giả tưởng” nằm trong dòng ý thức

Tolstoyan, được gợi hứng từ chiến thắng thời đại Nga Xô, 1942-43.

“Stalingrad” tới trước. Được xb dưới sự kiểm duyệt dưới dạng “For a

Just Cause” – “Vì Nghĩa Cả” – nó có những phần được xen vào theo đường

hướng của nhà nước, mang tính Đảng.

Vào năm 1956, sau khi Xì

ngỏm, một ấn bản mới cho phép tác giả thỏ thẻ có ý nghĩ riêng của mình,

nghĩa là lập lại, restore, khá nhiều giọng nói riêng của mình. Nhưng

không hơn con số 11 ấn bản của bản thảo, sống sót. Từ ấn bản này, dũng

mãnh, mẫn cảm và giầu có về mầu sắc, Robert and Elizaberth Chandler, đã

giữ lại được, và đưa vô lần xb “Đời và Số” vào năm 1956, cộng thêm phần

nguyên liệu mạnh mẽ nhất, chưa từng được in ra.

Một Homer về vùng sông Volga.

Hiệu quả là, 1 trận đánh bao la khác, một thứ mặt trận tiền phương, sôi

bỏng, chuyện thường ngày của thường xuyên bị vây hãm, và những cuộc

“lèm bèm” hoài hoài giữa họ, những người bị vây hãm. Lại 1 lần nữa,

Grossman đưa vô, biến thành nghệ thuật “tất cả nỗi khổ đau hoang dại, và

niềm hạnh phúc vất vưởng, không nơi cư nhập, hội tụ, của những năm

tháng khủng khiếp” đó. Lại 1 lần nữa, Grossman quyết định, biến những

con sóng “không cá nhân từng con người”, “không mặt mũi”, “vô ngã”

–impersonal - của lịch sử thế kỷ 20, thành những phần tử sáng ngời của

đời người.

Nỗi hiểm nguy của từng giờ, từng phút, ở mép bờ của

“xém huỷ diệt, xém tận thế” làm cho cái “giá trị của mọi cá nhân 1 con

người” – “the value of every individual” – sáng ngời ngời như chưa từng

bao giờ được như thế.

“Stalingrad” [tít đầu tiên của Grossman]

đưa vô rất nhiều nhân vật trở lại trong “Đời và Số”, đặc biệt là gia

đình được nới thêm lên – extended - của khoa học gia Alexandra

Shaposhnikova. Nhà vật lý học Do Thái, Viktor Shtrum, người con rể và

nhân vật hàm hồ của cuốn tiểu thuyết sau, ở đây, đóng 1 vai nhỏ hơn

nhưng vẫn là vai trò trung tâm. Ba thế hệ của lao động bộ lạc, yêu

đương và đánh lộn, trong khi Hồng Quân, trong cuộc triệt thoái hỗn loạn 1

ngàn cây số từ Đức, dừng bên bờ sông Volga. Sau cùng, vào cuối mùa hè

1942, con “sông sắt, và thép” của Xô Viết, bắt đầu “chảy ngược lại, từ

Đông qua Tây”.

Ở những điểm

tiền phương, những nhà máy, những trung tâm điện lực của Stalingrad chính nó, với

những chuyển đoạn, ở Moscow, Kazan, và ngay cả bộ tư lệnh Đức, Grossman vun vén

chừng trên chục những âm mưu, chuyển vào 1 câu chuyện kể, - a single narrative –

Ông chỉ ra, làm thế nào, “một cảm quan nhức nhối về thay đổi lịch sử” cắt sâu vào

những cơ thể mệt nhoài và những trí tưởng ủ ê của những nhân vật của ông. Những

xen chiến tranh ở Stanlingrad thì như đang xẩy ra trong 1 nhà máy rộng khắp, với

tiếng ồn của máy móc, có tất cả cái xúc động hớp hồn của chết chóc làm nhớ tới

“Đời và Số”. Tính trữ tình, sự dịu dàng, và cảm động của những khoảnh khắc nghỉ

ngơi, cũng đạt tới đỉnh cao như thế. Một đứa bé mồ côi, trong căn nhà dành cho

thiếu nhi, “không thể nói cho ai sự đau đớn của nó” nhưng cảm thấy an ủi từ 1

người lau dọn tốt bụng, 1 cảnh tượng như thế đánh động Grossman rất nhiều, và có

thể nói, vô cùng, so với những viên tướng, những lãnh tụ hy sinh hàng triệu con

người, coi như là những con tốt trên bàn cờ chiến thuật.

Tuy nhiên, có

sự khác biệt giữa hai tuyệt tác. Không như “Đời và Số”, viết sau khi Xì chết,

được viết 1 cách thoải mái, trong hy vọng về 1 tự do lớn lao hơn, Grossman thai

nghén những phần của cuốn trước, trong nghiệt ngã. Một số chương sách, về sự

lao động anh hùng ở chiến trường hay ở những bãi mìn, vọng lên 1 Hiện Thực Xã Hội

chủ nghĩa. Chỉ vài trang nhắc lại như 1 con vẹt về sự bãi bỏ tính chính thống độc

tôn của Đảng.

Grossman vẫn

tìm được những cung cách của ọng, để làm bật ra Lò Thiêu – ngay cả qua, như Ms

Popoff nhận xét – ông hoàn tất cuốn sách trong “chiến dịch của Xì chống lại ‘những

tên cosmopolitans không gốc rễ’ đang hăm he làm trò”. Những sĩ quan Đức thầm thì

về “một nhà máy thực thụ hành xử những tên Do Thái”.

Trên tất cả,

những nhân vật của ông mục kích, chứng tích, đau khổ, và phản ảnh tới chỉ -

with hyper-intensity - Nó làm sáng ngời gần

như mọi trang sách, như hào quang ở địa ngục làm sáng rực bầu trời Stalingrad.

Với cây rìu

Đức “đưa lên cao trong không gian” thành phố biến thành 1 Troy thứ nhì, và

Grossman, vị ‘bard” của nó.

****

Huế Mậu Thân,

Sài Gòn Biển Máu, Iliad… là cái quái gì ở đây? một trong những cô con gái của

Alezandra, hỏi, sau khi 1 người bạn trầm luân nhắc tới nàng công chúa bị cầm tù

ở Troy.

Giản dị thôi,

điều này: Vài tác phẩm văn học, kể từ Homer, có thể sánh được cái nhìn nhân bản,

nhức nhối không làm sao lay động, của Grossman, khi ông ngước nhìn bộ mặt rách

nát, tơi tả, phờ phạc của chiến tranh +

Bác đọc quyển này chưa – 832 trang, bây giờ

bán ở format de

poche rồi. Bác cốp theo kiểu này viết đi, lồng trong chế độ là cảnh đời

của

người dân. Bác có trí nhớ phi thường, bác không viết thì ai mà viết

được.

Tks

NQT

NQT

"Mort

de l'esclave

et réssurection de l'homme libre".

Dans ce roman-fresque,

composé dans les années 1950, à

la façon de Guerre et paix,

Vassili Grossman (1905-1964) fait revivre l'URSS en

guerre à travers le destin d'une famille, dont les membres nous amènent

tour à

tour dans Stalingrad assiégée, dans les laboratoires de recherche

scientifique,

dans la vie ordinaire du peuple russe, et jusqu'à Treblinka sur les pas

de

l'Armée rouge. Au-delà de ces destins souvent tragiques, il s'interroge

sur la

terrifiante convergence des systèmes nazi et communiste alors même

qu'ils

s'affrontent sans merci. Radicalement iconoclaste en son temps - le

manuscrit

fut confisqué par le KGB, tandis qu'une copie parvenait clandestinement

en

Occident -, ce livre pose sur l'histoire du XXe siècle une question que

philosophes et historiens n'ont cessé d'explorer depuis lors. Il le

fait sous

la forme d'une grande œuvre littéraire, imprégnée de vie et d'humanité,

qui

transcende le documentaire et la polémique pour atteindre à une vision

puissante, métaphysique, de la lutte éternelle du bien contre le mal.

Destin de Grossman

Vie et destin est l'un des chefs-d'oeuvre du XXème siècle. On n'en lisait pourtant qu'une version incomplète depuis que les manuscrits avaient été arrachés au KGB et à la censure. Celle que Bouquins propose désormais est la première intégrale. Elle a été révisée à partir de l'édition russe qui fait désormais autorité, celle de 2005, et traduite comme la précédente par Alexis Berelowitch et Anne Coldefy-Faucard. Raison de plus pour se le procurer. Ce volume sobrement intitulé Oeuvres (1152 pages, 30 euros) contient également une dizaine de nouvelles, le roman Tout passe, texte testamentaire qui dresse notamment le portrait d'une série de Judas, et divers documents dont une lettre à Kroutchtchev. Mais Vie et destin, roman dédié à sa mère par un narrateur qui s'adresse constamment à elle, demeurera l'oeuvre qui éclipse toutes les autres. La bataille de Stalingrad est un morceau d'anthologie, et, au-delà de sa signfication idéologique, la manière dont l'auteur passe subrepticement dans la ville de l'évocation du camp nazi au goulag soviétique est un modèle d'écriture. Toute une oeuvre parue à titre posthume.

Dans son éclairante préface, Tzvetan Todorov résume en quelques lignes "l'énigme" de Vassili Grossman (1905-1964) :

" Comment se fait-il qu'il soit le seul écrivain soviétique connu à avoir subi une conversion radicale, passant de la soumission à la révolte, de l'aveuglement à la lucidité ? Le seul à avoir été, d'abord, un serviteur orthodoxe et apeuré du régime, et à avoir osé, dans un deuxième temps, affronter le problème de l'Etat totalitaire dans toutes son ampleur ?"

On songe bien sûr à Pasternak et Soljenitsyne. Mais le préfacier, anticipant la réaction du lecteur, récuse aussitôt les comparaisons au motif que le premier était alors un écrivain de premier plan et que la mise à nu du phénomène totalitaire n'était pas au coeur de son Docteur Jivago ; ce qui n'est évidemment pas le cas du second avec Une Journée d'Ivan Denissovitch, à ceci près rappelle Todorov, qu'étant un inconnu dans le milieu littéraire, il n'avait rien à perdre. La métamorphose de Grossman est donc un cas d'école unique en son genre :"mort de l'esclave et réssurection de l'homme libre".

Bảnh hơn

Pasternak, bảnh hơn cả Solzhenitsyn, Tzvetan Todorov, trong lời tựa,

thổi Đời

& Số Mệnh của Grossman: Cái chết của tên nô lệ và sự tái

sinh của con người

tự do.Destin de Grossman

Vie et destin est l'un des chefs-d'oeuvre du XXème siècle. On n'en lisait pourtant qu'une version incomplète depuis que les manuscrits avaient été arrachés au KGB et à la censure. Celle que Bouquins propose désormais est la première intégrale. Elle a été révisée à partir de l'édition russe qui fait désormais autorité, celle de 2005, et traduite comme la précédente par Alexis Berelowitch et Anne Coldefy-Faucard. Raison de plus pour se le procurer. Ce volume sobrement intitulé Oeuvres (1152 pages, 30 euros) contient également une dizaine de nouvelles, le roman Tout passe, texte testamentaire qui dresse notamment le portrait d'une série de Judas, et divers documents dont une lettre à Kroutchtchev. Mais Vie et destin, roman dédié à sa mère par un narrateur qui s'adresse constamment à elle, demeurera l'oeuvre qui éclipse toutes les autres. La bataille de Stalingrad est un morceau d'anthologie, et, au-delà de sa signfication idéologique, la manière dont l'auteur passe subrepticement dans la ville de l'évocation du camp nazi au goulag soviétique est un modèle d'écriture. Toute une oeuvre parue à titre posthume.

Dans son éclairante préface, Tzvetan Todorov résume en quelques lignes "l'énigme" de Vassili Grossman (1905-1964) :

" Comment se fait-il qu'il soit le seul écrivain soviétique connu à avoir subi une conversion radicale, passant de la soumission à la révolte, de l'aveuglement à la lucidité ? Le seul à avoir été, d'abord, un serviteur orthodoxe et apeuré du régime, et à avoir osé, dans un deuxième temps, affronter le problème de l'Etat totalitaire dans toutes son ampleur ?"

On songe bien sûr à Pasternak et Soljenitsyne. Mais le préfacier, anticipant la réaction du lecteur, récuse aussitôt les comparaisons au motif que le premier était alors un écrivain de premier plan et que la mise à nu du phénomène totalitaire n'était pas au coeur de son Docteur Jivago ; ce qui n'est évidemment pas le cas du second avec Une Journée d'Ivan Denissovitch, à ceci près rappelle Todorov, qu'étant un inconnu dans le milieu littéraire, il n'avait rien à perdre. La métamorphose de Grossman est donc un cas d'école unique en son genre :"mort de l'esclave et réssurection de l'homme libre".

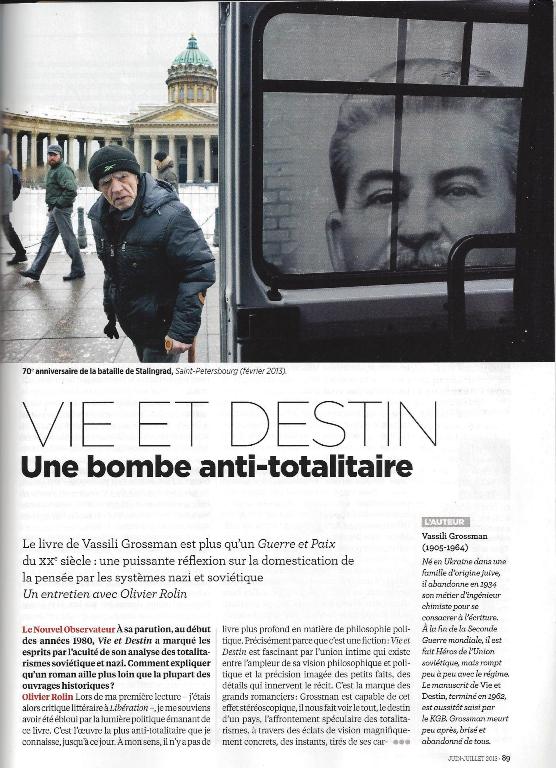

Tờ Obs, số đặc biệt về những tuyệt tác của văn học, kể ra hai cuốn cùng dòng, là Gulag của Solz, 1 cuốn sách lật đổ 1 đế quốc, và Vie & Destin của Grossman: Trái bom chống toàn trị.

TV sẽ giới thiệu bài phỏng vấn Ovivier Rolin, trên tờ Obs.

Smoke and dust

Vasily Grossman, the greatest bard of the second world war

Like “Life and Fate”, the newly translated “Stalingrad” is a masterpiece

Stalingrad: A Novel. By Vasily Grossman. Translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler. NYRB Classics; 1,088 pages; $27.95. Harvill Secker; £25.

Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century. By Alexandra Popoff. Yale University Press; 424 pages; $32.50 and £25.

DURING HIS final years, Vasily Grossman kept a few cherished mementoes in his shabby Moscow flat. One was a safety lamp presented by colleagues at the coal mine in the Donbas where, as a young chemist, he had worked to prevent explosions. Another was a child’s alphabet block he found after the liberation of the Treblinka extermination camp.

Born in 1905 to a Jewish family in Berdichev, now in Ukraine, Grossman (pictured) had entered the camp after gruelling front-line service as a Soviet war correspondent for the Red Army’s newspaper. In November 1944, in the journal Znamya, he published his essay “The Hell of Treblinka”. It ranks not only as one of the first eyewitness reports of the Holocaust, but, as Alexandra Popoff says in her scrupulous but impassioned biography, as a work with “the everlasting quality of genuine art”.

In an article he wrote in 1946 Grossman affirmed: “There is nothing more precious than human life; its loss is final and irreplaceable.” The miner’s lamp, the child’s alphabet, testify to his core beliefs. Yet as a fine journalist, then a peerless novelist of the horrors of war and tyranny, his destiny was to inhabit times and places that ground up human beings by the million. In his novel “Stalingrad”, which is only now being published in English, the sight of a dying old woman on a bombed boulevard prompts the anguished question: “Human suffering. Will it be remembered in centuries to come?” Or will the tears and despair disappear like “the smoke and dust blown across the steppe by the wind”? Grossman’s oeuvre, which includes what may be the greatest fiction of the second world war in any language, has helped salvage that suffering from oblivion.

Western readers mostly know Grossman for “Life and Fate”, his epic of the battle of Stalingrad and its aftermath. After its completion in 1960, the KGB confiscated the manuscript. Soviet censors decreed that the novel’s unflinching comparisons between the barbarism of Nazi and Stalinist regimes would make it unpublishable for 250 years. Its Jewish author’s vigilant attention to the anti-Semitism perpetrated by both systems embarrassed Soviet apparatchiks for decades.

Grossman died, poor and still under suspicion, in 1964. But by 1980 “Life and Fate” had reached the West via microfilm. In 1985 Robert Chandler’s magnificent translation primed the book for fame in the English-speaking world. Radio and stage adaptations have enhanced its reputation as the “War and Peace” of the 20th century.

The parallel with Tolstoy, which both blessed and plagued Grossman, dates to the early 1940s. Stalin himself, Ms Popoff reports, had “anticipated a Soviet ‘War and Peace’.” Grossman, once a protégé of the Soviet literary guru Maxim Gorky, seemed a prime candidate to write it. Indeed, together with “Life and Fate”, “Stalingrad” forms a consciously Tolstoyan fictional diptych inspired by the epoch-making Russian victory in 1942-43.

“Stalingrad” came first. Published in censored form as “For a Just Cause” in 1952, it contained sections reluctantly inserted to obey the party line. In 1956, after Stalin died, a new edition allowed Grossman to restore much of his own voice. But no fewer than 11 versions of the manuscript survive. For this translation, as forceful, sensitive and richly coloured as that of “Life and Fate”, Robert and Elizabeth Chandler have woven the strongest unpublished material into the 1956 version.

“Stalingrad” (Grossman’s original title) introduces many characters who return in “Life and Fate”, in particular the extended family of the scientist Alexandra Shaposhnikova. The Jewish physicist Viktor Shtrum, her son-in-law and the ambiguous hero of the later novel, here plays a smaller but still pivotal role. Three generations of the clan labour, love and fight as the Red Army’s chaotic, 1,000km retreat from the German invaders halts at the Volga. Finally, in the late summer of 1942, the Soviet “river of iron and steel” starts “flowing back, from east to west”.

In the front-line posts, factories and power-plants of Stalingrad itself, with interludes in Moscow, Kazan and even in the German high command, Grossman knits a dozen plot strands into a single narrative. He shows how “a lacerating sense of historical change” cuts deep into the exhausted bodies and brooding minds of his characters. The battle scenes set in Stalingrad’s “vast, rumbling smithy” have all the mesmeric thrill and dread that admirers will recall from “Life and Fate”. The lyricism, tenderness and pathos of the moments of respite touch the same heights. An orphaned boy in a children’s home who “could not tell anyone his pain”, but finds comfort from a kindly cleaner, matters as much to Grossman—or rather, infinitely more—than the generals and leaders who sacrifice millions of pawns on their strategic chessboards.

There are, though, differences between the two masterworks. Unlike “Life and Fate”, written after Stalin’s death in the hope of greater freedom, Grossman drafted parts of the earlier book under duress. Some chapters of heroic labour in the fields or mines echo Socialist Realist doctrine. A very few pages parrot the sloganeering uplift of party orthodoxy.

Grossman still finds ways to spotlight the Holocaust—even though, as Ms Popoff notes, he completed the book as “Stalin’s campaign against ‘rootless cosmopolitans’ was picking up steam”. German officers mutter about “a real factory for processing Jews”. Above all, his characters witness, suffer and reflect with a hyper-real intensity. It illuminates nearly every page like the hellish glow that lights up the night sky over Stalingrad. With the German axe “raised high in the air”, the city becomes a second Troy, and Grossman its bard.

“What on earth’s the ‘Iliad’ got to do with it?” asks one of Alexandra’s daughters after a doomed friend refers to a captive Trojan princess. Simple: few works of literature since Homer can match the piercing, unshakably humane gaze that Grossman turns on the haggard face of war. ◼

Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century. By Alexandra Popoff. Yale University Press; 424 pages; $32.50 and £25.

DURING HIS final years, Vasily Grossman kept a few cherished mementoes in his shabby Moscow flat. One was a safety lamp presented by colleagues at the coal mine in the Donbas where, as a young chemist, he had worked to prevent explosions. Another was a child’s alphabet block he found after the liberation of the Treblinka extermination camp.

Born in 1905 to a Jewish family in Berdichev, now in Ukraine, Grossman (pictured) had entered the camp after gruelling front-line service as a Soviet war correspondent for the Red Army’s newspaper. In November 1944, in the journal Znamya, he published his essay “The Hell of Treblinka”. It ranks not only as one of the first eyewitness reports of the Holocaust, but, as Alexandra Popoff says in her scrupulous but impassioned biography, as a work with “the everlasting quality of genuine art”.

In an article he wrote in 1946 Grossman affirmed: “There is nothing more precious than human life; its loss is final and irreplaceable.” The miner’s lamp, the child’s alphabet, testify to his core beliefs. Yet as a fine journalist, then a peerless novelist of the horrors of war and tyranny, his destiny was to inhabit times and places that ground up human beings by the million. In his novel “Stalingrad”, which is only now being published in English, the sight of a dying old woman on a bombed boulevard prompts the anguished question: “Human suffering. Will it be remembered in centuries to come?” Or will the tears and despair disappear like “the smoke and dust blown across the steppe by the wind”? Grossman’s oeuvre, which includes what may be the greatest fiction of the second world war in any language, has helped salvage that suffering from oblivion.

Western readers mostly know Grossman for “Life and Fate”, his epic of the battle of Stalingrad and its aftermath. After its completion in 1960, the KGB confiscated the manuscript. Soviet censors decreed that the novel’s unflinching comparisons between the barbarism of Nazi and Stalinist regimes would make it unpublishable for 250 years. Its Jewish author’s vigilant attention to the anti-Semitism perpetrated by both systems embarrassed Soviet apparatchiks for decades.

Grossman died, poor and still under suspicion, in 1964. But by 1980 “Life and Fate” had reached the West via microfilm. In 1985 Robert Chandler’s magnificent translation primed the book for fame in the English-speaking world. Radio and stage adaptations have enhanced its reputation as the “War and Peace” of the 20th century.

The parallel with Tolstoy, which both blessed and plagued Grossman, dates to the early 1940s. Stalin himself, Ms Popoff reports, had “anticipated a Soviet ‘War and Peace’.” Grossman, once a protégé of the Soviet literary guru Maxim Gorky, seemed a prime candidate to write it. Indeed, together with “Life and Fate”, “Stalingrad” forms a consciously Tolstoyan fictional diptych inspired by the epoch-making Russian victory in 1942-43.

“Stalingrad” came first. Published in censored form as “For a Just Cause” in 1952, it contained sections reluctantly inserted to obey the party line. In 1956, after Stalin died, a new edition allowed Grossman to restore much of his own voice. But no fewer than 11 versions of the manuscript survive. For this translation, as forceful, sensitive and richly coloured as that of “Life and Fate”, Robert and Elizabeth Chandler have woven the strongest unpublished material into the 1956 version.

Homer on the Volga

The result is another huge, seething fresco of front-line combat, domestic routine under siege, and restless debate. Again, Grossman transforms into art “all the savage grief and homeless happiness of those terrible years”. Again, he resolves the impersonal waves of 20th-century history into brilliant particles of human life. The peril of each hour on the brink of destruction makes “the value of every individual” shine brighter than ever before.“Stalingrad” (Grossman’s original title) introduces many characters who return in “Life and Fate”, in particular the extended family of the scientist Alexandra Shaposhnikova. The Jewish physicist Viktor Shtrum, her son-in-law and the ambiguous hero of the later novel, here plays a smaller but still pivotal role. Three generations of the clan labour, love and fight as the Red Army’s chaotic, 1,000km retreat from the German invaders halts at the Volga. Finally, in the late summer of 1942, the Soviet “river of iron and steel” starts “flowing back, from east to west”.

In the front-line posts, factories and power-plants of Stalingrad itself, with interludes in Moscow, Kazan and even in the German high command, Grossman knits a dozen plot strands into a single narrative. He shows how “a lacerating sense of historical change” cuts deep into the exhausted bodies and brooding minds of his characters. The battle scenes set in Stalingrad’s “vast, rumbling smithy” have all the mesmeric thrill and dread that admirers will recall from “Life and Fate”. The lyricism, tenderness and pathos of the moments of respite touch the same heights. An orphaned boy in a children’s home who “could not tell anyone his pain”, but finds comfort from a kindly cleaner, matters as much to Grossman—or rather, infinitely more—than the generals and leaders who sacrifice millions of pawns on their strategic chessboards.

There are, though, differences between the two masterworks. Unlike “Life and Fate”, written after Stalin’s death in the hope of greater freedom, Grossman drafted parts of the earlier book under duress. Some chapters of heroic labour in the fields or mines echo Socialist Realist doctrine. A very few pages parrot the sloganeering uplift of party orthodoxy.

Grossman still finds ways to spotlight the Holocaust—even though, as Ms Popoff notes, he completed the book as “Stalin’s campaign against ‘rootless cosmopolitans’ was picking up steam”. German officers mutter about “a real factory for processing Jews”. Above all, his characters witness, suffer and reflect with a hyper-real intensity. It illuminates nearly every page like the hellish glow that lights up the night sky over Stalingrad. With the German axe “raised high in the air”, the city becomes a second Troy, and Grossman its bard.

“What on earth’s the ‘Iliad’ got to do with it?” asks one of Alexandra’s daughters after a doomed friend refers to a captive Trojan princess. Simple: few works of literature since Homer can match the piercing, unshakably humane gaze that Grossman turns on the haggard face of war. ◼

Comments

Post a Comment