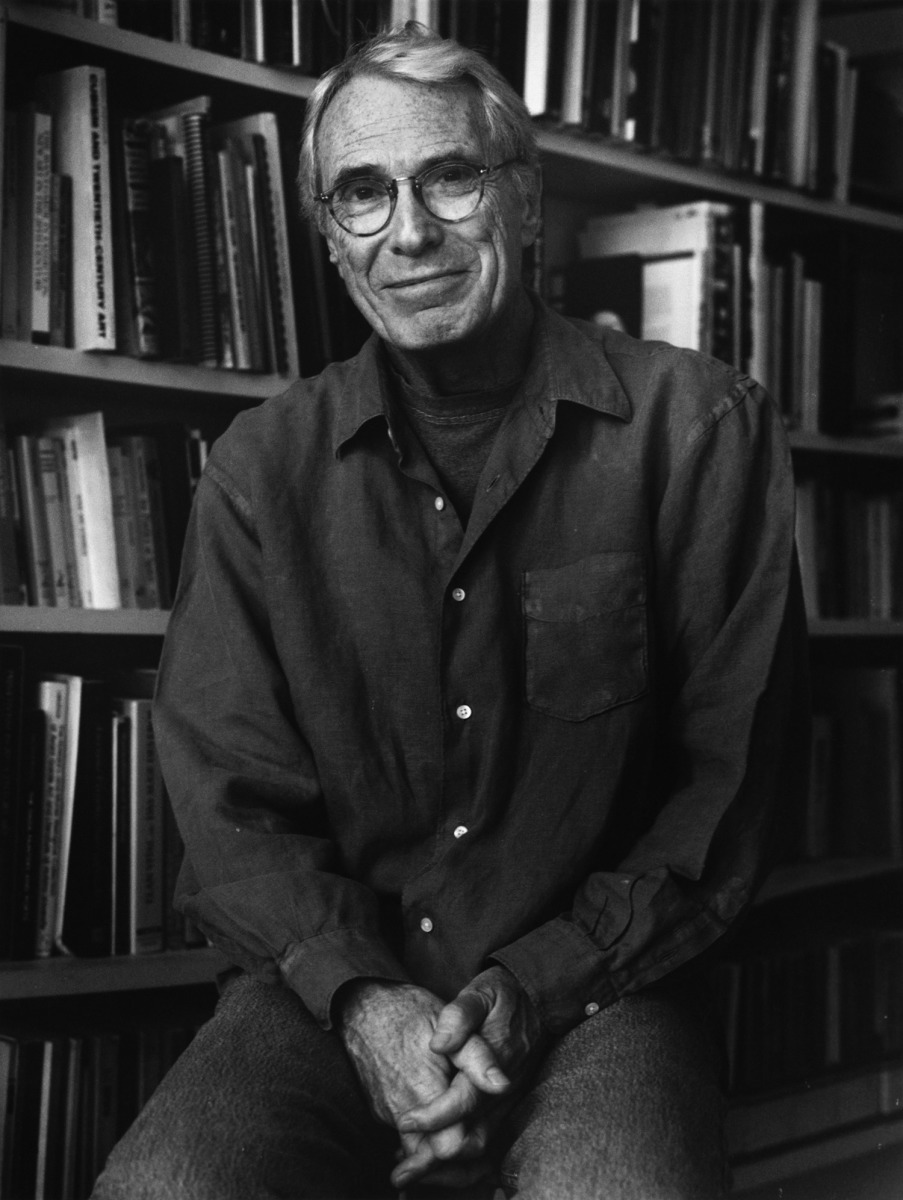

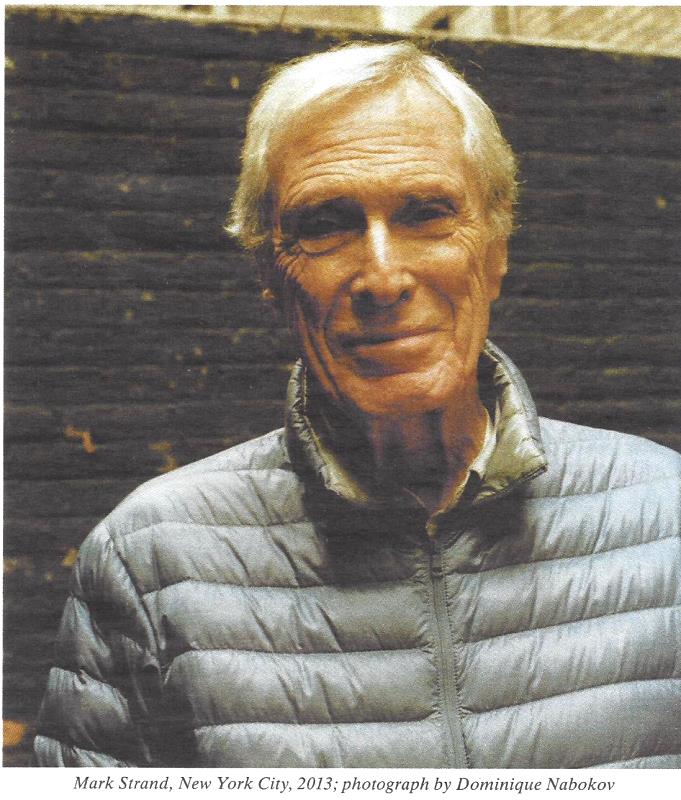

Mark Strand Tribute

Why the Germans? Why the Jews? Envy, Race Hatred, and the Prehistory of the Holocaust

by Götz Aly, translated from the German by Jefferson Chase

Metropolitan, 290 pp., $30.00

The German regime, with majority support in the Reichstag, had persecuted Catholics in the 1870s and repressed socialists in the 1880s, while noisy, single- issue anti-Semitic parties led by obvious cranks all failed to find political traction. That Jewish emancipation remained intact in Germany in the late nineteenth century owed neither to a liberal-democratic political culture devoted to protecting individual rights nor to the absence of agitating Jew-baiters.

The great paradox facing any scholar wrestling with the “prehistory” of the Holocaust, then, is to explain how the land of golden opportunity for Jews in the late nineteenth century became transformed in less than four decades into the land of their murderers. In a continent with a millennial tradition of anti-Semitism, what was peculiar about Germany and its variant of anti- Semitism that produced this lethal result? That is the question Götz Aly tackles in his new book, Why the Germans? Why the Jews? Envy, Race Hatred, and the Prehistory of the Holocaust.

Götz

Aly, a freelance historian, is one of the most innovative and

resourceful scholars working in the field of Holocaust studies. Time and

again he has demonstrated an uncanny ability to find hitherto untapped

sources, frame insightful questions, and articulate clear if often

challenging and controversial arguments. He is a scholar whose works I

have always found necessary and rewarding to read, even though I have on

occasion found myself in substantial disagreement with him.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Aly and his coauthor Susanne Heim argued for an economic causality of the Holocaust.1

In their view a cluster of economic and demographic experts, who

constituted the “planning intelligentsia” for designing the Nazi New

Order, wanted to break the vicious circle of poverty, low economic

productivity, and rural overpopulation that afflicted Eastern Europe.

According to this theory, Polish Jews in particular constituted a

“superfluous” population whose monopolizing of the preindustrial

handicraft industry prevented both rationalization of industrial

production and the movement of Polish peasants off the land into the

cities.A removal of the Jews and confiscation of their property would reduce rural overpopulation, modernize agriculture, and prepare the way for both rationalized large-scale manufacturing and the emergence of an urban Polish middle class with a stake in the German New Order. Thus the “planning German intelligentsia longed for the Final Solution that appeared logical to them at the time” and carried out the decisive planning without which the regime would not have moved beyond pogroms and massacres to systematic genocide.

In his “Final Solution”: Nazi Population Policy and the Murder of the European Jews, Aly argued for a causal connection between Nazi demographic plans and the Final Solution.2 In a continual attempt to “Germanize” territory targeted as Nazi Lebensraum by resettling ethnic Germans and displacing Slavs and Jews, Jews were always the ethnic group left standing when the music stopped in this escalating game of demographic musical chairs. With no place to put Jews after four failed resettlement schemes, a consensus formed among frustrated Nazis—with no order from an aloof and detached Hitler—to murder them instead.

In Hitler’s Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State, Aly argued that the Nazi regime was able to mobilize and preserve popular support for itself, its crimes, and its doomed war effort to the very end because the German people had been bribed and corrupted by material gain wrapped in the idealistic guise of equal opportunity and social harmony for the German Volk while excluding, of course, marginalized and targeted minorities.3 This winning of popular support of the majority through “dispensing favors” was achieved by minimal taxation on Germans, the hyperexploitation of the occupied territories, and the confiscation of Jewish property throughout Europe. But in the end Aly went much further, arguing that rather than any ideological vision, from the beginning “concern for the welfare of Germans was the decisive motivation behind policies of terrorizing, enslaving, and exterminating enemy groups.”

Beyond

a very laudable ability to identify new topics and ferret out new

sources, two tendencies have appeared in Aly’s past work. The first has

been to downplay Nazi ideology in general and anti-Semitism in

particular as mere propaganda and rhetoric and to attribute causation in

Nazi Germany to “rational” or “logical” calculations about material and

demographic factors.

The

second has been to document an ever-widening circle of complicity, as

Aly exposes the involvement of various cadres of experts hitherto

self-proclaimed as apolitical technocrats, many with respectable postwar

careers, and finally the corrupt complicity of most of the German

population. If the first tendency might strike some as exculpatory by

downplaying Germans’ personal animosity toward Jews, whose persecution

and murder end up being portrayed as the byproduct or collateral damage

of other priorities and programs, the moral indignation of the second

tendency is palpable. Indeed, one theme of Aly’s work has been to

suggest a significant continuity between the Nazi era and postwar

Germany by implying that much of the criminality of the Nazi regime was

not committed by distant and alien ideological fanatics but rather by

the educated elites of German society whose “rational” outlook and

approach to problem-solving were not fundamentally different between the

two eras.Over several decades I have criticized Aly’s various theses. Concerning his claim that consensus among a cluster of modernizing technocrats was the key driving force behind the emergence of the Final Solution in Poland, I argued that the lower-echelon planners in Poland were quite divided, and that a majority of them (whom I dubbed the “productionists”) supported the utilitarian use of Jewish labor and temporarily prevailed over their rival “attritionists.” Only decisive intervention from Berlin led to the systematic destruction of Polish Jewry.4 I shared Aly’s view that Nazi population policy and “resettlement” schemes were tightly connected to the evolution of Nazi Jewish policy from 1939 to 1941, but I argued that the Nazi assault upon the Jews then gained an autonomy and priority of its own and that Hitler and his hatred of Jews were much more directly involved in the decision-making process that led to the Final Solution than Aly credited.5

I praised Aly’s effort to assess the importance of material factors in determining the German people’s attitudes toward the genocidal Nazi regime, but criticized the direction of his argument. In my view he flipped what had been framed as a facilitating factor into the decisive driving force behind war and genocide, displacing Hitler’s vision of a racial revolution supported by a broad popular consensus about German victimization, superiority, and entitlement to empire.6 Given Aly’s past tendency to downplay ideological factors as rhetorical cover for material factors, I was very intrigued to see how he would treat the subject of German anti-Semitism in his most recent book on the “prehistory” of the Holocaust.

Aly anchors his

explanation in the threefold impact of the French Revolution and

Napoleonic occupation on a fragmented Germany. First, an uneven and

incremental process of Jewish emancipation in the different German

states during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, initiated by

elites but opposed by much of the population, transformed Jewish life.

Armed with a culture of education and freed from past restrictions, Jews

quickly seized the economic opportunities offered by modernization,

urbanization, and industrialization. Educationally unprepared Germans

nostalgically tied to traditional ways of life moved into cities and

took up new occupations only reluctantly. Spectacular Jewish advance

contrasted with German lethargy, resentment, and disorientation,

producing envy of Jewish wealth and success as well as fear and a sense

of inferiority vis-à-vis Jewish competition.

Second, a negative

reaction to the Napoleonic occupation poisoned German attitudes toward

the democratic ideals of liberty and equality, and third, the continued

division of Germany led to an insecure national identity and lack of

confidence that promoted and valued collectivist politics over

individual rights and freedom. In short, the seeds of the future Nazi

combination of anti-Semitism and illiberal collectivist nationalism were

planted.Aly does not place as much emphasis on the failed liberal-democratic and national movements of the revolution of 1848 (the infamous turning point in German history that did not turn) as he does on the intense burst of modernization, urbanization, industrialization, and “boom and bust” that followed German unification in 1871. The resulting intensifying of social tensions aggravated the already existing dynamic of Jewish betterment and Gentile envy. This Germany was “ripe” for anti-Semitic agitators (such as Heinrich von Treitschke, Wilhelm Marr, and Adolf Stöcker) who defined the “Jewish question” as the “social question” behind all of Germany’s modern ills.

Despite the trauma of defeat and revolution, as well as the humiliating and debilitating Versailles Treaty, in Aly’s view the Weimar Republic was not doomed to fail from the start. Rather its surprising successes raised expectations that could not be fulfilled. The opening of the educational system and the newly fluid social structure created many aspiring social climbers who, after hopes were engendered during the boom of the mid-1920s, found themselves totally blocked and even slipping back in the bust of 1929. World War I had made the German middle class more socialist and the Socialists more nationalist, and in the humiliation and bitterness of defeat Hitler conjoined these two movements with anti-Semitism, explaining German defeat, division, and poverty as the fault of the Jews, and offering social advancement, ethnic unity, and national recovery to the “Aryan” population. Facing numerous rival parties, each with a limited social base, Hitler alone was able to attract a cross-section of society and create the one political party transcending class, religion, and region.

Not all Nazi voters were anti-Semitic, but they at least tolerated Nazi anti-Semitism. Once in power Hitler and other Nazi leaders may have made decisions based on ideology, material interest, and political calculation, but they needed the approval of a politically active minority and the “silent tolerance” and “tacit” complicity of the larger majority to provide a social basis for the state persecution of the Jews.

But how to explain this “moral insensibility” and “moral torpor” of 1933–1945, which underpinned the “criminal collaboration” between the German people and the Nazi regime? One factor, as Aly argued earlier in Hitler’s Beneficiaries, was material gain. As Jewish jobs and apartments came open and Jewish property was redistributed, all too many benefited directly. But for indifference to and even schadenfreude over the fate of the pushy and overachieving Jews, Germans also needed a “new morality” that justified discrimination, plunder, and murder.

It is here that Aly finally turns to the issue of racial theory, which he examines not as a system of thought but rather on the basis of its psychological attractiveness to Germans at this particular historical juncture. For those consumed by envy of Jews but ashamed of this tawdry motive, race theory concealed their embarrassment. For those suffering a deep inferiority complex about Jews, race theory inverted success and failure, turning Jewish accomplishment into evidence of Jewish vice. For those troubled by the large difference between Jews they knew and the Nazi stereotype, race theory allowed individual experience to be ignored.

Above all, race theory turned persecution and murder into self-defense, requiring “pitiless” cleansing in the present to achieve a future Utopian happiness and social harmony. “Biopolitical pseudoscience,” Aly concludes,

disguised hatred as insight and made one’s own shortcomings seem like virtues. It also provided justification for acts of legal discrimination against others, allowing millions of Germans to delegate their own aggression, born of feelings of inferiority and shame, to their state.And this “passively expressed anti-Semitism gave the German government the latitude it needed to press forward with its murderous campaigns.”

In some regards Aly’s conclusions coincide with important previous work. Peter Pulzer’s classic The Rise of Political Anti-Semitism in Germany and Austria

diagnosed the rise of German anti-Semitism as an antimodernist response

of those who felt most disadvantaged by nineteenth-century progress.7 Albert Lindemann has emphasized the catalytic impact on Germans of nineteenth-century Jewish success.8

In their pioneering works on German popular attitudes toward Nazi

persecution of the Jews, Ian Kershaw and Otto Dov Kulka both

distinguished between ardent Nazis and the general population and, using

the terms “indifference” and “passive complicity” respectively, tried

to capture the responsibility of the latter in facilitating the crimes

of the former.9

But Aly, working almost entirely in pre-1933 sources to capture the

unguarded words and feelings of those who did not yet know the outcome

and thus “had little reason to conceal anti-Semitic attitudes,” does not

directly engage the previous historiography of this topic.

If to

some degree Aly is treading the same ground as others before him, in

other ways the book is a remarkably fresh look at an old problem. He

focuses not just on the writings of the self-proclaimed and notorious

anti-Semites, but on other contemporary documents and studies that

reveal less explicit but widely held assumptions and attitudes. Unique

among his documents is his own extensive family archive, from which he

offers various illustrative, unspectacular, but telling life stories of

average Germans from Munich and Freiburg.Insofar as Aly is taking aim at other historical approaches, he is subtly criticizing the Sonderweg or “special path” thesis of German social historians of the second generation after World War II. This generation quite responsibly wanted to explain how and why Germany departed from the liberal-democratic political trajectory of the Western democracies. They hoped to explain the Nazi era as the result of long-term German historical developments and not, in the manner of many in their preceding generation, to be passed off on the one hand as some aberrational ahistorical accident or on the other hand as a misfortune to be blamed merely on the victors’ having imposed upon Germany both a vengeful treaty and an alien democracy in 1918–1919.

In the narrative of the Sonderweg historians, hopes for a liberal-democratic unification of Germany in 1848 were quashed due to a successful counterrevolution. Unlike other Western democracies, Germany became a modern industrial power still ruled by entrenched old elites, who fought off pressures for political reform and democratization through cynical manipulation and distraction, and finally the gamble on war and conquest in 1914.

Unreconciled to the defeat and democracy, the Old Right made its last bid to restore revanchist authoritarianism in Germany by “holding the stirrups” for Hitler in 1933. One overlapping issue of agreement for this partnership between the Old Right of national conservatives and the New Right of the Nazis was anti-Semitism. In 1945 the right-wing legacy of authoritarianism, imperialism, and anti-Semitism was broken for good, and Germany could finally join the community of Western democracies.

In

earlier works Aly has exposed the Nazi careers of many respectable

postwar figures, challenging the notion that Germany’s 1945 break with

the past was as genuinely complete as claimed, particularly among the

academics and technocrats who had served the Nazi regime as fellow

travelers. And in this book Aly certainly rejects the notion that

anti-Semitism was a monopoly of the right wing. Some of the most telling

voices he chooses to illustrate anti-Semitic attitudes come from the

left.

Moreover Aly begins his story not with the

liberal-democratic revolution of 1848 that was sabotaged by the right

wing, but with the attempts of some leaders, such as the reforming

Prussian chancellor Karl August von Hardenberg, to initiate Jewish

emancipation against the opposition of most of the population following

the Napoleonic wars. That is the historiographical subtext of his

otherwise obscure statement in the introduction:Those who merely hand out blame, in an attempt to feel as though they are on the right side of German history, will never be able to explain how a majority of Germans came to support the official state goal of getting rid of Jews.Aly’s emphasis on emotion (in this case envy) and psychology (concerning the reception of race theory), to say nothing of the topic of anti-Semitism itself, represents a significant departure from his earlier work. Here is a creative scholar who continues to grow in remarkable ways. In Aly’s portrayal the German paradox alluded to above disappears. If the Jews of Germany experienced the greatest success of any Jewish community in Europe in assimilation, social mobility, and the attainment of wealth and preeminence, they did so amid a Gentile population for which the modernization experience was more compressed, intense, and disorienting than in other countries. If envy of Jewish success was the driving motive behind modern anti-Semitism, as Aly argues, then it would be logical rather than paradoxical that the most intense anti-Semitic reaction would also occur in Germany, the land of the greatest and most visible Jewish success. This in my opinion is the most important contribution of Why the Germans? Why the Jews?

In any discussion of German anti-Semitism and the Holocaust, a comparative perspective is always helpful. If we return to George Mosse’s imagined conversation in 1900, it becomes apparent how quickly and drastically the historical context changed thereafter. In France the defenders of Dreyfus prevailed and the Third Republic staggered to victory in 1918, thus obtaining an additional two decades before the French anti-Semites returned to power with a vengeance in the Vichy regime of 1940. In Russia, the tsar was overthrown, and following victory in a bloody civil war the new Soviet regime preferred to destroy additional millions of its own people primarily on the basis of class rather than ethnicity. In Germany a rapid succession of catastrophes—total war, defeat, revolution, hyperinflation, and the Great Depression—opened the way to power for the ardent anti-Semites who had hitherto been marginalized, and it was they—not the previously more prominent anti-Semites in France or Russia—who would exploit the envy, jealousy, greed, and indifference of the wider population not just in Germany, but in other countries as well to murder the Jews of Europe.

-

1

Götz Aly and Susanne Heim, “The Economics of the Final Solution: A Case Study from the General Government,” Simon Wiesenthal Center Annual, Vol. 5 (1988), and Architects of Annihilation: Auschwitz and the Logic of Destruction (Princeton University Press, 2002), first published in German in 1991. ↩

-

2

Oxford University Press, 1999; originally published in German in 1995. ↩

-

3

Metropolitan, 2007; originally published in German in 2005. ↩

-

4

Christopher R. Browning, “German Technocrats, Jewish Labor, and the Final Solution: A Reply to Götz Aly and Susanne Heim,” The Path to Genocide: Essays on Launching the Final Solution (Cambridge University Press, 1992). ↩

-

5

Christopher R. Browning, “Völkermord aus der Sicht der NS-Ethnokraten,” Neue Politische Literatur, Vol. 41, No. 1 (1996). ↩

-

6

Christopher R. Browning, “Review Forum: Götz Aly, Hitlers Volksstaat,” Journal of Genocide Research, Vol. 9, No. 2 (June 2007). ↩

-

7

Wiley, 1964. ↩

-

8

Esau’s Tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews (Cambridge University Press, 1997). ↩

-

9

Ian Kershaw, “The Persecution of the Jews and German Public Opinion in the Third Reich,” Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1981); Otto Dov Kulka, “‘Public Opinion’ in Nazi Germany and the ‘Jewish Question,’” The Jerusalem Quarterly, Nos. 25 and 26 (Fall and Winter 1982). ↩

Trước khi về Lào ăn Tết Mít với lũ nhỏ, GCC đọc vội tờ NYRB, bài tưởng niệm nhà thơ Mẽo mới mất. Và có đi vài hàng về bài này.

Về lại Canada, nhân cái chân trái đang làm eo, bèn nằm 1 chỗ, và lôi tờ báo ra đọc tiếp, thì phát giác ra 1 bài thần sầu:

How Envy of Jews Lay Behind ItThe historian George Mosse liked to tell a hypothetical story: if someone had predicted in 1900 that within fifty years the Jews of Europe would be murdered, one possible response would have been: “Well, I suppose that is possible. Those French or Russians are capable of anything.”In Memory of Joseph Brodsky

It could be said, even here, that what remains of the self

Unwinds into a vanishing light, and thins like dust, and heads

To a place where knowing and nothing pass into each other, and

through;

That it moves, unwinding still, beyond the vault of brightness ended,

And continues to a place which may never be found, where the

unsayable,

Finally, once more is uttered, but lightly, quickly, like random rain

That passes in sleep, that one imagines passes in sleep.

What remains of the self unwinds and unwinds, for none

Of the boundaries holds-neither the shapeless one between us,

Nor the one that falls between your body and your voice. Joseph,

Dear Joseph, those sudden reminders of your having been-the

places

And times whose greatest life was the one you gave them-now

appear

Like ghosts in your wake. What remains of the self unwinds

Beyond us, for whom time is only a measure of meanwhile

And the future no more than et cetera et cetera ... but fast and

forever.

Mark Strand: New Selected Poems

Trong bài viết của ông, về Mark Strand, được tờ NYRB cho đăng lại, cùng với bài của Charles Simic, như 1 tưởng niệm, Brodsky kể, lần đầu tiên ông đọc thơ Mark Strand, khi còn ở Liên Xô.

Bài cũng ngắn, Tin Văn scan và giới thiệu độc giả liền sau đây, cùng bài thơ của Mark Strand tưởng niệm Brodsky, và một… giai thoại liên quan tới Brodsky, Mark Strand và... nữ văn sĩ Thảo Trần, tức Gấu Cái!Brodsky viết, thơ của Mark Strand là thứ thơ mà thi sĩ không vặn tay độc giả đến trẹo cả xương, bắt phải đọc:

Technically speaking, Strand is a very gentle poet: he never twists your arm, never forces you into a poem.

GCC đã sử dụng đòn này, để nói về văn của Gấu Cái, nhân đọc bài viết của Thảo Trường, khi anh đọc "Nơi Dòng Sông Chảy Về Phía Nam" (1):

"Viết như không viết".

Tếu hơn nữa, là, 1 tay blogger bèn chôm liền cụm từ này, để nói về 1 em chân dài, trong 1 show trình diện trước công chúng Mít, ở trong nước:

Mặc như không mặc!

On Mark Strand (1934-2014)The poet Mark Strand, a contributor to these pages, died on November 29.JOSEPH BRODSKYThe following was given by Joseph Brodsky as an introduction to a reading by Mark Strand at the American Academy of Poets in New York City on November 4, 1986.It's a tall order to introduce Mark Strand because it requires estrangement from what I like very much, from something to which I owe many moments of almost physical happiness-or to its mental equivalent. I am talking about his poems-as well as about his prose, but poems first.

A man is, after all, what he loves. But one always feels cornered when asked to explain why one loves this or that person, and what for. In order to ex-plain it-which inevitably amounts to explaining oneself-one has to try to love the object of one's attention a little bit less. I don't think I am capable of this feat of objectivity, nor am I willing even to try. In short, I feel biased about Mark Strand's poems, and judging by the way his work progresses, I expect to stay biased to the end of my days.

My romance with Mr. Strand's poems dates back to the end of the Sixties, or to the beginning of the Seventies, when an anthology of contemporary American poetry-a large paperback brick (edited by, I think, among others, Mark Strand) landed one day on my lap. That was in Russia. If my memory serves me right, Strand's entry in that anthology contained one of the best poems written in the postwar era, his "The Way It Is," with that terrific epigraph from Wallace Stevens that I can't resist reproducing here:The world is ugly,

and the people are sad.

What impressed me there and then was a peculiar unassertiveness in depicting fairly dismal, in this poem's case, aspects of the human condition. I was also impressed by the almost effortless pace and grace of the poem's utterances. It became apparent to me at once that I was dealing with a poet who doesn't put his strength on display-quite the contrary, who displays a sort of flabby muscle, who puts you at ease rather than imposes himself on the reader.

This impression has stayed with me for some eighteen years, and even now I don't see that much reason for modifying it. Technically speaking, Strand is a very gentle poet: he never twists your arm, never forces you into a poem. No, his opening lines usually invite you in, with a genial, slightly elegiac sweep of intonation, and for a while you feel almost at home on the surface of his opaque, gray, swelling lines, until you realize-and not suddenly, with a jolt, but rather gradually and out of your own idle curiosity, the way one some- times looks out a skyscraper's window or overboard of a rowboat-how many fathoms are there underneath, how far you are from any shore. What's more, you'll find that depth, as well as that impossibility of return, hypnotic.But his strategies aside, Mark Strand is essentially a poet of infinities, not of affinities, of things' cores and essences, not so much of their applications. Nobody can evoke absences, silences, emptinesses better than this poet, in whose lines you hear not regret but rather respect for those nonentities that surround and often engulf us. A usual Strand poem, to paraphrase Frost, starts in a recognition yet builds up to a reverie-a reverie toward infinity encountered in a gray light of the sky, in the curve of a distant wave, in a case, however, we encounter the real thing: as real as it was in the case of Zbigniew Herbert or of Max Jacob, though I doubt very much that either was Strand's inspiration. For while those two Europeans were, very roughly putting it, carving their remarkable cameos of absurdity, Strand's prose poems-or rather, prose-looking poems-unleash themselves with the maddening grandeur of purely lyrical eloquence. These pieces are great, crackpot, unbridled orations, monologues whose chief driving force is pure linguistic energy, mulling over clichés, bureaucratese, psychobabble, literary passages, scientific lingo-you name missed chance, in a moment of hesitation. I often thought that should Robert Musil write verse, he'd sound like Mark Strand, except that when Mark Strand writes prose, he sounds not at all like Musil but rather like a cross between Ovid and Borges.Joseph Brodsky

But before we get to his prose, which I admire enormously and the reception of which in our papers I find nothing short of idiotic, I'd like to urge you to listen to Mark Strand very carefully, not because his poems are difficult, i.e., hermetic or obscure-they are not- but because they evolve with the immanent logic of a dream, which calls for a somewhat heightened degree of attention. Very often his stanzas resemble a sort of slow-motion film shot in a dream that selects reality more for its open-endedness than for mechanical cohesion. Very often they give a feeling that the author managed to smuggle a camera into his dream. A reader more reckless than I would talk about Strand's surrealist techniques; I think about him as a realist, a detective, really, who follows himself to the source of his disquiet.

I also hope that he is going to read tonight some of his prose, or some of his prose poems. One winces at this definition, and rightly so. In Strand's it-past absurdity, past common sense, on the way to the reader's joy.

Had that writing been coming from the Continent, it would be all the rage on our island. As it is, it is coming from Salt Lake City, Utah, and while being grateful to the land of the Mormons for giving shelter to this writer, we should be in all honesty a bit ashamed for not being able to provide him with a place in our midst. -

A man is, after all, what he loves.

Brodsky

Nói cho cùng, một thằng đàn ông là "cái" [thay bằng "gái", được không, nhỉ] hắn yêu."What", ở đây, nghĩa là gì?

Một loài chim biển, được chăng?The world is ugly,

and the people are sad.Đời thì xấu xí

Người thì buồn thế!The Good LifeYou stand at the window.

There is a glass cloud in the shape of a heart.

The wind's sighs are like caves in your speech.

You are the ghost in the tree outside.The street is quiet.

The weather, like tomorrow, like your life,

is partially here, partially up in the air.

There is nothing you can do.The good life gives no warning.

It weathers the climates of despair

and appears, on foot, unrecognized, offering nothing,

and you are there.Một đời OKMi đứng ở cửa sổ

Mây thuỷ tinh hình trái tim

Gió thở dài sườn sượt, như hầm như hố, trong lèm bèm của mi

Mi là con ma trong cây bên ngoàiPhố yên tĩnh

Thời tiết, như ngày mai, như đời mi

Thì, một phần ở đây, một phần ở mãi tít trên kia

Mi thì vô phương, chẳng làm gì được với cái chuyện như thế đóMột đời OK, là một đời đếch đề ra, một cảnh báo cảnh biếc cái con mẹ gì cả.

Nó phì phào cái khí hậu của sự chán chường

Và tỏ ra, trên mặt đất, trong tiếng chân đi, không thể nhận ra, chẳng dâng hiến cái gì,

Và mi, có đó!IN MEMORIAM

Give me six lines written by the most honourable of men,

and I will find a reason in them to hang him.-RichelieuWe never found the last lines he had written,

Or where he was when they found him.

Of his honor, people seem to know nothing.

And many doubt that he ever lived.

It does not matter. The fact that he died

Is reason enough to believe there were reasons.IN MEMORIAMChúng ta không kiếm ra những dòng cuối cùng hắn viết

Cho ta sáu dòng được viết bởi kẻ đáng kính trọng nhất trong những bực tu mi

Và ta sẽ tìm ra một lý do trong đó để treo cổ hắn ta

-Richelieu

Hay hắn ở đâu, khi họ tìm thấy hắn

Về phẩm giá của hắn, có vẻ như người ta chẳng biết gì

Và nhiều người còn nghi ngờ, có thằng cha như thế ư

Nhưng cũng chẳng sao, nói cho cùng

Sự kiện hắn ngỏm là đủ lý do để mà tin rằng có những lý do. -

WINTER IN NORTH LIBERTYSnow falls, filling

The moonlit fields.

All night we hear

The wind on the drifts

And think of escaping

This room, this house,

The reaches of ourselves

That winter dulls.Pale ferns and flowers

Form on the windows

Like grave reminders

Of a summer spent.

The walls close in.

We lie apart all night,

Thinking of where we are.

We have no place to go.

ELEVATOR1.The elevator went to the base-

ment. The doors opened.

A man stepped in and asked if I

was going up.

"I'm going down," I said. "I won't

be going up."2.The elevator went to the base-

ment. The doors opened.

A man stepped in and asked if

I was going up.

"I'm going down," I said. "I won't

be going up."Mark Strand (born 11 April 1934) is a Canadian-born American poet, essayist, and translator. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1990. Since 2005–06, he has been a professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University.Strand was born on Summerside, Prince Edward Island, Canada. His early years were spent in North America, while much of his teenage years were spent in South and Central America. In 1957, he earned his B.A. from Antioch College in Ohio. Strand then studied painting under Josef Albers at Yale University where he earned a B.F.A in 1959. On a Fulbright Scholarship, Strand studied nineteenth-century Italian poetry in Italy during 1960–1961. He attended the Iowa Writers' Workshop at the University of Iowa the following year and earned a Master of Arts in 1962. In 1965 he spent a year in Brazil as a Fulbright Lecturer.Tell yourself

as it gets cold and gray falls from the air

that you will go on

walking, hearing

the same tune no matter where

you find yourself—

inside the dome of dark

or under the cracking white

of the moon's gaze in a valley of snow.

Tonight as it gets cold

tell yourself

what you know which is nothing

but the tune your bones play

as you keep going. And you will be able

for once to lie down under the small fire

of winter stars.

And if it happens that you cannot

go on or turn back

and you find yourself

where you will be at the end,

tell yourself

in that final flowing of cold through your limbs

that you love what you are.

Mark Strand, 1934 - 2014.

Credit PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS FELVER / GETTY

Page-Turner

November 30, 2014

Mark Strand’s Last Waltz

By Dan ChiassonThe passing of Mark Strand returns us to his poems and to his fine “Collected Poems,” published this year and long-listed for the National Book Award. Strand’s poems are often about the inner life’s methods of processing its social manifestations. He wrote poetry in quiet and private; on trains, he wrote prose, because it was “less embarrassing,” as he told his friend Wallace Shawn in Strand’s Paris Review interview: “Who would understand a man of my age writing poems on a train, if they looked over my shoulder? I would be perceived as an overly emotional person.” Strand was an “overly emotional person,” but his courtesy warred with his intensity. How gallant to think of the passenger beside him, whose rights extend to not being seated next to a handsome stranger scribbling verses.

At least since “Reasons For Moving” (1968), his second volume, Strand surveyed his outward circumstances—relative health and prosperity, growing fame, the undeniable good fortune of being alive—from a peephole cut into the exterior wall of his solitude. The weirdness was all out there, where a suave and handsome man named Strand moved among other columns of flesh and bone; in here, alone with the moods, the mind, our memories of childhood and love, we found what Strand called, in his book-length poem of this name, “The Continuous Life.” It could be harrowing, but it was never proprietary: we all shared the same secret; Strand’s poems of the inner life were sometimes like expressions of our own: “some shy event, some secret of the light that falls upon the deep/Some source of sorrow that does not wish to be discovered yet.” (“Our Masterpiece Is the Private Life.”)

“The Continuous Life” continues after death, whose abrupt appearance, breaking up the party, Strand often described. Life is a waltz, a “Delirium Waltz,” as he called it in his greatest poem—collected in his best book, one of the finest of the past fifty years, “Blizzard of One”—which ends when the music ends. It is in the nature of waltzes that we cannot foretell their duration ahead of time. Waltzing to delirium, we might think that they never end. And then the music stops. It happened on Saturday for Strand, a great poet and a kind man. Here is “2002,” one of the bleakly comic poems he wrote in anticipation of that moment:I am not thinking of Death, but Death is thinking of me.

He leans back in his chair, rubs his hands, strokes

His beard and says, “I’m thinking of Strand, I’m thinking

That one of these days I’ll be out back, swinging my scythe

Or holding my hourglass up to the moon, and Strand will appear

In a jacket and tie, and together under the boulevards’

Leafless trees we’ll stroll into the city of souls. And when

We get to the Great Piazza with its marble mansions, the crowd

That had been waiting there will welcome us with delirious cries,

And their tears, turned hard and cold as glass from having been

Held back so long, will fall, and clatter on the stones below.

O let it be soon. Let it be soon.”

Joseph Brodsky and Charles Simic

January 8, 2015 Issue

The poet Mark Strand, a contributor to these pages, died on November 29.

Note: Tin Văn sẽ đi bài này, từ báo giấy, tất nhiên!JOSEPH BRODSKYThe following was given by Joseph Brodsky as an introduction to a reading by Mark Strand at the American Academy of Poets in New York City on November 4, 1986.It’s a tall order to introduce Mark Strand because it requires estrangement from what I like very much, from something to which I owe many moments of almost physical happiness—or to its mental equivalent. I am talking about his poems—as well as about his prose, but poems first.A man is, after all, what he loves. But one always feels cornered when asked to explain why one loves this or that person, and what for. In order to explain it—which inevitably amounts to explaining oneself—one has to try to love the object of one’s attention a little bit less. I don’t think I am capable of this feat of objectivity, nor am I willing even to try. In short, I feel biased about Mark Strand’s poems, and judging by the way his work progresses, I expect to stay biased to the end of my days.My romance with Mr. Strand’s poems dates back to the end of the Sixties, or to the beginning of the Seventies, when an anthology of contemporary American poetry—a large paperback brick (edited by, I think, among others, Mark Strand) landed one day on my lap. That was in Russia. If my memory serves me right, Strand’s entry in that anthology contained one of the best poems written in the postwar era, his “The Way It Is,” with that terrific epigraph from Wallace Stevens that I can’t resist reproducing here:The world is ugly,

and the people are sad.What impressed me there and then was a peculiar unassertiveness in depicting fairly dismal, in this poem’s case, aspects of the human condition. I was also impressed by the almost effortless pace and grace of the poem’s utterances. It became apparent to me at once that I was dealing with a poet who doesn’t put his strength on display—quite the contrary, who displays a sort of flabby muscle, who puts you at ease rather than imposes himself on the reader.This impression has stayed with me for some eighteen years, and even now I don’t see that much reason for modifying it. Technically speaking, Strand is a very gentle poet: he never twists your arm, never forces you into a poem. No, his opening lines usually invite you in, with a genial, slightly elegiac sweep of intonation, and for a while you feel almost at home on the surface of his opaque, gray, swelling lines, until you realize—and not suddenly, with a jolt, but rather gradually and out of your own idle curiosity, the way one sometimes looks out a skyscraper’s window or overboard of …

*

A man is, after all, what he loves.

Nói cho cùng, một thằng đàn ông là "cái" [thay bằng "gái", được không, nhỉ] hắn yêu."What", ở đây, nghĩa là gì?

Một loài chim biển, được chăng?The world is ugly,

and the people are sad.Đời thì xấu xí

Người thì buồn thế!ELEVATOR1.The elevator went to the base-

ment. The doors opened.

A man stepped in and asked if I

was going up.

"I'm going down," I said. "I won't

be going up."2.The elevator went to the base-

ment. The doors opened.

A man stepped in and asked if

I was going up.

"I'm going down," I said. "I won't

be going up."

Comments

Post a Comment