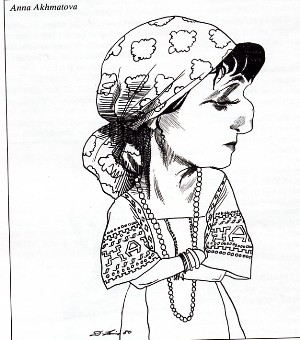

Anna Akhmatova

He glances sideways, looks, sees, recognizes,

And instantly puddles shine

As melted diamonds, ice pines.

In lilac haze repose backyards,

Station platforms, logs, leaves, clouds.

The whistle of a steam engine, the crunch of watermelon rind,

In a fragrant kid glove, a timid hand.

He rings out, thunders, grates, he beats like the surf

And suddenly grows quiet-it means that he

Is cautiously advancing through the pines,

So as not to disturb the light sleep of space.

And it means that he is counting the grains

From the stripped stalks, it means that he

Has come back to a Daryal gravestone, cursed and black,

After some kind of funeral.

And once more, Moscow weariness burns the throat,

Far off, a deadly little bell is ringing ...

Who lost his way two steps from the house,

Up to the waist in snow and no way out?

Because he compared smoke to the Laocoon,

And celebrated cemetery thistles,

Because he filled the world with the new sound

Of his verse reverberating in new space-

He was rewarded with a kind of eternal childhood,

His generosity and keen-sightedness shone,

The whole earth was his inheritance

And he shared it with everyone

Akhmatova

Trong "Akhmatova, Thi sĩ & Tiên tri", Roberta Reeder đưa ra 1 bản dịch khác, bài thơ Akhmatova làm tặng Pasternak, và cho biết thêm nhiều chi tiết, sự kiện liên quan đến nó. Trong Hội nghị của những nhà văn Liên Xô, 1936 [bài thơ làm tháng Giêng 1936], Pasternak tấn công nhà nước Liên Xô, đúng hơn, chủ nghĩa hiện thực XHCN: lệnh lạc từ trên đưa xuống, its commands from above on how to write, saying: "Art is unthinkable without risk and spiritual self-sacrifice; freedom and boldness of imagination have to be gained in practice... Don't expect a directive on this score". Pat phán, nghệ thuật không thể ngửi được [không thể suy nghĩ được], nếu không có rủi ro và sự hy sinh cái ngã tinh thần... Tự do và đởm lược chỉ có được qua thực tiễn, thực hành. Đảng biết mẹ gì về nó mà đòi chỉ đạo? Mặc dù Pat giúp đỡ Mandelstam khi gặp khó khăn, nhưng ông cảnh cáo M về hậu quả của chuyện làm thơ chống Xì, the consequences of writing satires and serious poems against Stalin: Đây không phải là 1 sự kiện văn chương mà là 1 hành động tự sát. Tôi không ủng hộ, approve, và không thích thú có phần ở trong đó. Tuy nhiên khi M bị bắt, ông đứng bên cặp vợ chồng, và dám đến thăm viếng bà vợ, khi nghe tin M chết.

Bài thơ có những chi tiết liên quan tới cuộc đời tác phẩm của Pat, thành thử rất khó dịch. GCC phải tra kíu ba bản dịch mới dám thỏ thẻ, rụt rè đưa ra bản tiếng Mít!

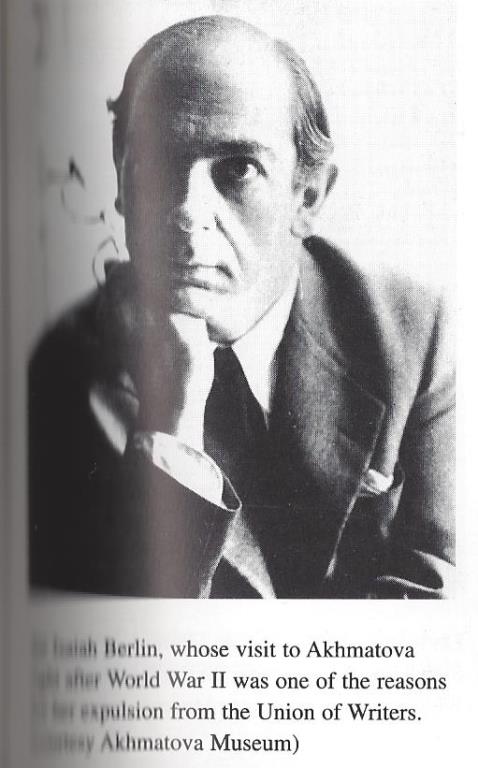

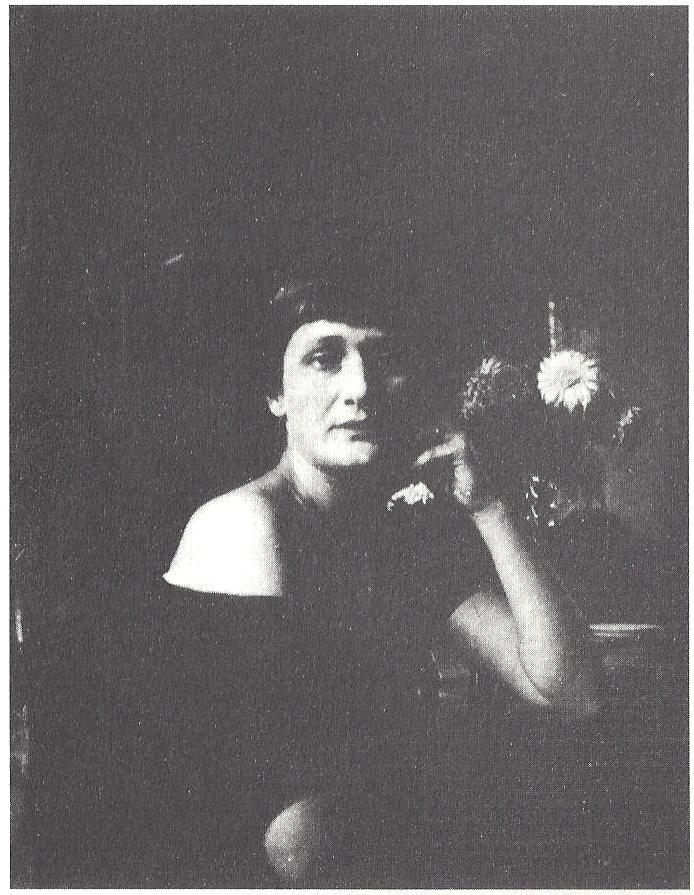

Berlin có 1 thời là

người yêu của Akhmatova. Trong cuốn "Akhmatova,

thi sĩ, nhà tiên tri", có nhắc tới mối tình

của họ.

Berlin là nguyên

mẫu của “Người khách từ tương lai”, "Guest from

the future", trong “Bài thơ không nhân vật”, “Poem without

a Hero”.

Cuộc gặp gỡ của

cả hai, được báo cáo cho Xì, và Xì phán,

như vậy là nữ tu của chúng ta đã gặp gián điệp

ngoại quốc, “This mean our nun is now receiving visits

from foreign spies”.

Cuộc gặp gỡ của

họ đậm mùi chiến tranh lạnh. Và thật là tuyệt

vời.

Vào ngày Jan 5,

1946, trước khi về lại Anh [Berlin khi đó là

Thư ký thứ nhất của Tòa ĐS Anh ở Moscow], Berlin xin

gặp để từ biệt.

Kết quả là chùm

thơ “Cinque”, làm giữa Nov 26, 1945 và Jan

11, 1946. Những bài thơ tình đẹp nhất và bi đát

nhất của ngôn ngữ Nga.

Bài dưới đây,

viết ngày 20 Tháng Chạp, Akhmatova ví cuộc

lèm bèm giữa đôi ta như là những cầu vồng đan vô nhau:

Sounds die away in the ether,

And darkness overtakes

the dusk.

In a world become

mute for all time,

There are only

two voices: yours and mine.

And to the almost

bell-like sound

Of the wind from

invisible Lake Ladoga,

That late-night

dialogue turned into

The delicate shimmer

of interlaced rainbows.

(II, p. 237)

Tiếng buồn nhạt nhòa

vào hư vô

Và bóng tối lướt lên cõi chạng vạng

Trong một thế giới trở thành câm nín đời đời

Vưỡn còn, chỉ hai giọng, của anh và của em

Và cái âm thanh giống như tiếng chuông

Của gió, từ con hồ Ladoga vô hình

Cuộc lèm bèm muộn trong đêm – hay, trong đêm

muộn –

Biến thành hai cái cầu vồng

Lù tà mù, mờ mờ ảo ảo, lung la lung linh

Quấn quít – hay, cuống quít - cuộn vào nhau.

The last poem of the cycle, written on January 11, 1946, was more prophetic than Akhmatova realized:

We hadn't breathed the poppies'

somnolence,

And we ourselves

don't know our sin.

What was in our

stars

That destined

us for sorrow?

And what kind

of hellish brew

Did the January

darkness bring us?

And what kind

of invisible glow

Drove us out of

our minds before dawn?

Bài thơ chót

trong chuỗi thơ, hoá ra còn tiên tri hơn nhiều, so với dự đoán của

Anna Akhmatova:

Chúng ta

không thở cái mơ mơ màng của 1 tên phi xì ke

Và chúng ta, chính chúng ta, chẳng biết tội lỗi

của mình

Điềm triệu nào, ở những vì sao của chúng ta

Phán, đây là nỗi u sầu phiền muộn của tụi mi?

Thứ men bia quỉ quái nào

Bóng tối tháng giêng mang tới cho chúng ta?

Nhiệt tình vô hình nào

Kéo chúng ta ra khỏi thần trí, trước rạng đông?

(II, p. 239)

In 1956, something unexpected happened: the man who was to become "Guest from the Future" in her great work Poem Without a Hero-Isaiah suddenly returned to Russia. This was the famous "meeting that never took place”. In her poem, "A Dream" (August 14, 1956), Akhmatova writes:

This dream was prophetic or

not prophetic . . .

Mars shone among

the heavenly stars,

Becoming crimson,

sparkling, sinister-

And that same

night I dreamed of your arrival.

It was in everything

... in the Bach Chaconne,

And in the roses,

which bloomed in vain,

And in the ringing

of the village bells

Over the blackness

of ploughed fields.

And in the autumn,

which came close

And suddenly,

reconsidering, concealed itself.

Oh my August,

how could you give me such news

As a terrible

anniversary?

(II, p. 247)

Another poem, "In a Broken Mirror" (1956), has the poet compare Petersburg to Troy at the moment when Berlin came before, because the gift of companionship that he brought her turned out to poison her subsequent fate:

The gift you gave me

Was not brought

from altar.

It seemed to you

idle diversion

On that fiery

night

And it became

slow poison

In may enigmatic

fate.

And it was the

forerunner of all my misfortunes-

Let’s not remember

it! ...

Still sobbing

around the corner is

The meeting that

never took place.

Sir Isaiah Berlin. Cuộc thăm viếng Anna Akhmatova của ông liền sau Đệ Nhị Thế Chiến, là một trong những lý do khiến bà bị tống ra khỏi Hội Nhà Văn .

This land isn't native to me and still

It's given me memories time can't erase,

In its sea, water is tenderly chill,

Of salt it bears not a single trace.

The air intoxicates like wine,

Under the sea is sand, chalk-white.

And the rosy body of every pine

Is denuded as sunset beckons night.

And the sunset itself in waves of ether

Is such that I can't say with certainty

Whether day is ending, or the world, or whether

The secret of secrets is again in me.

1964-1965

Anna Akhmatova

Đất này không phải là quê hương của tôi

Nhưng nó vẫn cho tôi những hồi ức thời gian không thể xóa nhòa

Trong biển của nó, nước lành lạnh

Không 1 tì vết của muối

Khí trời làm say, như rượu vang

Biển, cát, trắng như phấn

Và mỗi cây thông

Thì hồng hồng

Như một em cởi truồng, và nắng bèn ngoạm em một vài phát

Khi buổi chiều gật gù, nhường chỗ cho màn đêm.

Và hoàng hôn, chính nó, thì như những đợt ê te

Chính vì thế mà tớ không sao phán chính xác

Về ngày đang hết,

Hay thế giới,

Hay,

Niềm bí ẩn của những bí ẩn

Lại ngoạm luôn cả tớ

Actors gone deaf or painters gone blind,

It's the same loss when women find

Time has made them no longer gorgeous.

But do not try to keep or protect

That which was given to you from heaven:

We know we're supposed to be like leaven-

We're condemned to squander, not to collect.

So walk alone, and heal the blind,

That in the difficult hour of doubt

You may see your disciples mock and gloat,

And note the indifference of the crowd.

1915

Mất tình cảm thực và lời thực

Khiến chúng ta,

Kịch sĩ trở thành điếc và họa sĩ, mù.

Cũng 1 thứ mất mát như thế

Khi đờn bà nhận ra

Thời gian khiến họ không còn lộng lẫy như xưa

Nhưng đừng cố gắng gìn giữ, hay bảo vệ

Cái mà Thượng Đế ban cho từ Thiên Đàng:

Chúng ta biết, chúng ta phải giống như là men cay/say

Chúng ta bị kết án phải ban phát, và rất cần hoang phí

[Đờn bà rộng miệng thời… sang, như lũ Mít thường nói]

Đừng thu gom, lượm lặt

Vậy thì, hãy bước một mình, và hãy chữa lành người mù

Rằng, vào cái giờ khó khăn của hồ nghi

Bạn có thể nhìn thấy lũ đệ tử chế nhạo và hể hả

Và nhận ra sự dửng dung của thế nhân.

Give me illness for years on end,

Shortness of breath, insomnia, fever.

Take away my child and friend,

The gift of song, my last believer.

I pray according to Your rite,

After many wearisome days,-

That the storm cloud over Russia might

Turn white and bask in a glory of rays.

1915

Anna Akhmatova

Hãy cho ta bịnh tật dài dài cho tới chết

Hơi thở đứt đoạn, cụt lủn, mất ngủ, nóng sốt

Lấy đi con của ta, bạn của ta

Tài ca hát, tín đồ cuối cùng của ta.

Ta cầu nguyện, theo như luật của Ngài

Sau nhiều ngày ngán ngẩm, mệt mỏi

Một trận mây bão phủ lên nền trời Nga Xô

Trở thành trắng và sưởi ấm

Trong cái huy hoàng của những sợi nắng

When they invented dreams and made them flower,

They didn’t have enough to go around,

We saw the same one, but it had power

In it, as spring first hits the ground

1965

Anna Akhmatova

Thay vì lời bạt

Khi họ phịa ra những giấc mộng, và biến chúng thành hoa, thành bông

Họ phịa không đủ

Có thể vì thế mà GCC nhìn thấy, chỉ có một

Đúng như thế

Nhưng bông hồng đen có đủ quyền uy ở trong nó

Như cú đánh đầu tiên của Mùa Xuân

Giáng xuống mặt đất

It's good there's no one left to lose,

And I can cry. The air in this town of the tsars

Was made to repeat songs, no matter whose.

A willow among the September brushes

Touches the water, bright and clear.

Risen from the past, my shadow rushes

In silence to meet me here.

So many lyres hang on this tree,

But it seems there's room for mine among these.

And this rain, sparse and sunny,

Is my good tidings and my ease.

1944

Anna Akhmatova

Linh hồn những người thân thương của tôi thì ở nơi những vì sao cao thật cao

Thật là được quá đi mất, chẳng còn ai ở dưới này để mất

Và tôi có thể khóc.

Không khí trong thành phố của những vì nga hoàng

Thì được làm ra

Để lập lại những bài hát, của ai thì cũng được

Một cây liễu giữa đám cây Tháng Chín

Chạm mặt nước, sáng và trong

Mọc lên từ quá khứ, cái bóng của tôi, vội vã,

Trong im lặng

Gặp tôi ở đó

Rất nhiều cây đàn lia treo trên cây

Nhưng hình như vẫn có chỗ cho tôi ở đó

Và cơn mưa này, lưa thưa và nhuộm nắng

Là những tin mừng và sự nhàn hạ của tôi

I called death down on the heads of those I cherished.

One after the other, their deaths occurred.

I cannot bear to think how many perished.

These graves were all predicted by my word.

As ravens circle above the place

Where they smell fresh-blooded limbs,

So my love, with triumphant face,

Inflicted its wild hymns.

Being with you is sweet beyond mention,

You're as close as the heart I call my own.

Give me both hands, pay careful attention,

I beseech you: go away, leave me alone.

Don't let me know where you make your homes.

Oh, Muse, don't call to him from above,

May he live, unmentioned in my poems,

Ignorant of all my love.

1921

Tôi gọi cái chết giáng xuống những người thân thương của tôi

Người này tiếp nối người kia, cái chết của họ xẩy ra.

Tôi không thể chịu nổi, bao nhiêu người đã tàn lụi

Những nấm mồ của họ thì đều được báo trước bằng lời của tôi

Như cú liệng trên trời

Nơi mùi máu vẫn còn đọng ở nơi xương cốt, tứ chi của họ

Và, như thế, tình yêu của tôi, với bộ mặt thắng trận

Chích điệu nhạc của nó.

Ở bên anh, hạnh phúc nào bằng

Cận kề đến nỗi em lầm trái tim của anh, là của em

Đưa cả hai tay anh cho em, này, hãy cẩn thận

Em năn nỉ: Anh hãy đi đi, bỏ mặc em một mình

Đừng nói cho em biết nhà mới của anh ở đâu

Ôi, Nữ Thần Thi Ca của tôi, đừng ở trên cao, kêu gọi anh ta

Cầu cho anh ta sống, không được nhắc tới trong những bài thơ của tôi

Không biết 1 tí gì về tình yêu của tôi

Dành cho anh ta.

This craft of ours, sacred and bright,

Has lasted too many years to tell . . .

The world is lit by it without light,

But, still, a poet has yet to dwell

On the thought that there's no wisdom or hell,

No age and, perhaps, no death as well.

1944

Anna Akhmatova

Thủ bản này -Tứ Tấu Khúc - của chúng ta, thiêng liêng và sáng ngời

Nó sẽ sống dài dài rất nhiều năm để kể….

Thế giới được chiếu sáng nhờ nó, đếch cần đến ánh sáng

Tuy nhiên, thi sĩ Gấu Cà Chớn thì vưỡn cư ngụ - trong căn nhà của hữu thể, thì cứ chôm đại chữ của Heidegger –

Khư khư với cái ý nghĩ, là,

Làm đếch gì có minh triết, hay địa ngục

Không tháng năm, tuổi tác, thế hệ, thời kỳ cái con mẹ gì hết

Và có lẽ

Đếch có, luôn, cả, cái chết!

My falling stars, my dark endeavor.

You were bitterness, lies, a bill of goods.

You weren't a consolation-ever.

1961

Mi dẫn ta vô một cánh rừng không lối đi

Những vì sao rơi rụng của ta, nỗi cố gắng âm u của ta

Chỉ là cay đắng, dối trá, đồ dởm

Niềm an ủi ư, không bao giờ!

A poet has a secret relationship with everything that he has ever written and this often is at odds with what the reader thinks about one poem or another.

For example, in my first book, Evening (1912), I really only like the lines:

Becoming intoxicated by the sound of a voice,

That resembles yours."

I even think that a lot of things in my poetry came out of those lines.

On the other hand, I very much like a somewhat dark and not at all typical poem of mine: "I came to take your place, sister," which has remained without sequel. I like the lines: And the tambourine's beat is no longer heard, And I know, the silence is frightening."

What the critics still mention often leaves me completely indifferent.

[Nhật ký]

Thi sĩ thì thể nào cũng có 1 liên hệ thầm kín, với mọi câu thơ mà mình đã từng viết ra.

Tôi cực mê câu thơ sau đây.

Có thể nói, mọi cái gì gọi là thơ của tôi, đều từ câu thơ đó, mà ra:

Tôi nhiễm độc xì ke từ 1 giọng nói

Giọng của Em, giọng Bắc Kít

Giọng BHD

Một con bé Bắc Kít, 11 tuổi

Hà, hà!

Murky, a Tartar claim.

It sticks a pin in my bubble,

The name for this name is trouble.

1962

U ám, có mùi Hung Nô

Chích 1 phát vô cái bong bóng của ta

Đúng là 1 cái tên làm phiền ta

As her protégé Joseph Brodsky writes:

Khi biết cô gái rượu của mình tính in thơ trên một tờ báo ở St. Petersburg, ông bố bèn bảo, rằng bố cũng không cấm cản một việc làm như vậy - làm thơ, và rồi in thơ - nhưng theo bố, đừng đem xấu xa đến cho dòng họ nhà mình, con nên tìm một bút hiệu. Và thế là “Anna Akhamatova” đi vào văn học Nga, thay vì “Anna Gorenko”.

The five open a's of Anna Akhmatova had a hypnotic effect and put this name's carrier firmly at the top of the alphabet of Russian poetry. In a sense, it was her first successful line .... This tells you a lot about the intuition and quality of the ear of this seventeen-year-old girl who soon after her first publication began to sign her letters and legal papers as Anna Akhmatova.

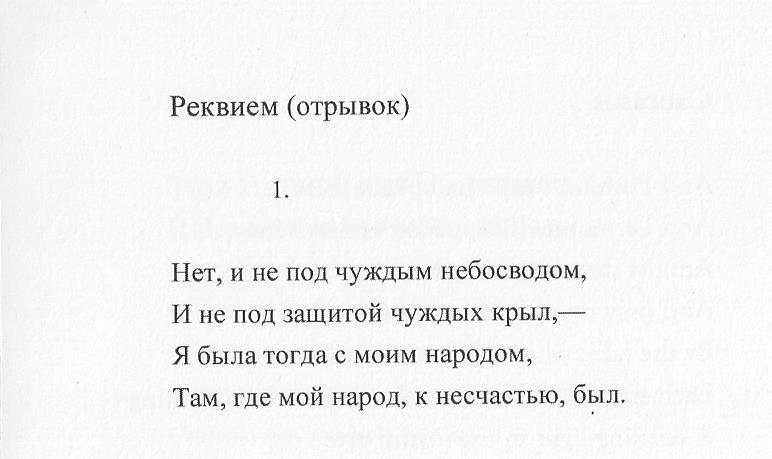

Requiem

I never sought asylum among aliens

Never cowled myself in a crow's wings.

I stood as my people stood, alone-

In my marrowbones, their sorrow.

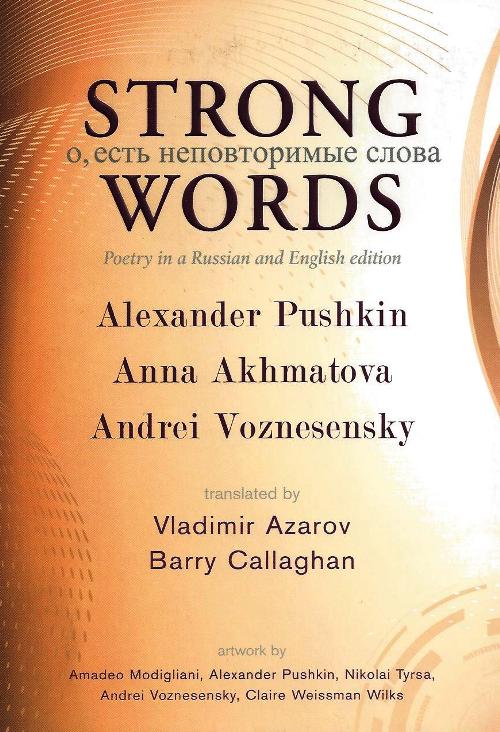

[Translated by Vladimir Azarov & Barrry Callahan, in Strong Words]

REQUIEM

No, it wasn't under a foreign heaven,

It wasn't under the wing of a foreign power,-

I was there among my countrymen,

I was where my people, unfortunately, were.

1961

[Translated by Lyn Coffin]

++++

Không, không phải dưới thiên đàng ngoại

Không phải dưới cánh quyền lực ngoại

Tôi ở giữa đồng bào tôi

Dân tộc tôi, bất hạnh,

Ở

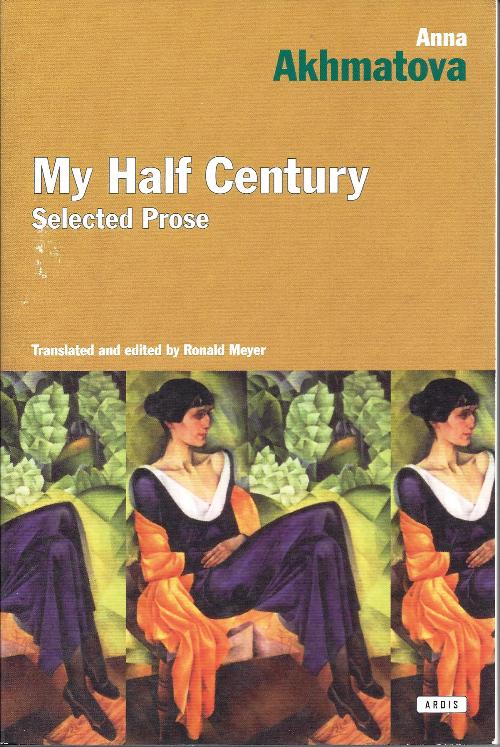

Anna: Nửa thế kỷ của tôi

Hôm nay là ngày sinh của Anna Akhmatova, nữ thi sĩ Nga. Nếu còn sống thì hôm nay bà tròn 125 tuổi.

Cảm nhận của mình về thơ bà luôn rất phức tạp, gần gũi nhưng xa lạ, đáng yêu nhưng cũng đáng sợ... Tuy nhiên, dù sao chăng nữa thì thơ bà cũng rất hay.

Anna Akhmatova

* * *

Ánh sáng

chiều tà mênh mang vàng úa

Lạnh mát tháng tư dịu ngọt vô cùng.

Anh đã đến muộn – nhiều năm lắm,

Nhưng dù sao vẫn khiến em mừng.

Hãy ngồi

lại đây, gần em một chút

Và hãy nhìn bằng cặp mắt vui tươi

Đây, cuốn vở bìa xanh này đấy

Là những vần thơ em viết thuở thiếu thời

Em xin lỗi, vì

sống trong buồn bã

Và ít khi vui với mặt trời

Em xin lỗi, vì em đã tưởng

Và nhầm anh với rất nhiều người.

1915

Bản tiếng Anh, trong Poems, selected and translated by Lyn Coffin:

The coolness of April is dear.

You, of course, are several years late,

Even so, I'm happy you're here.

Sit close at hand and look at me,

With those eyes, so cheerful and mild:

This blue notebook is full, you see,

Full of poems I wrote as a child.

Forgive me, forgive me, for having grieved

For ignoring the sunlight, too.

And especially for having believed

That so many others were you.

1915

V/v SN của AA

Late at night. Monday. The twenty-third.

The capital's outlines in the mists.

Some idiot's given us the word,

He's informed the world that love exists.

And out of boredom or laziness

Everyone believes and lives that way:

They all look forward to trysts, no less,

They sing their love songs night and day.

But to some, the secret's revealed,

The smallest silence weighs like a brick.

I too stumbled on what was concealed.

Since then I've felt as if I was sick.

1917

Cách đọc & cảm nhận thơ Bà, của những người Miền Bắc, theo GCC, do thiếu hẳn 1 nửa thông tin về Bà, do nhà nước Xô Viết thiến bỏ, nên không làm sao nhận ra được tầm vóc thơ & con người của Bà, như những dòng sau đây, trong bài giới thiệu Nửa Thế Kỷ Của Tôi, cho thấy. Nhân SN/AA, Tin Văn sẽ đi bài Intro của Brodsky, sau được in với cái tít The Kneeling Muse.

And fame carne sailing, like a swan

From golden haze unveiled,

While you, love, augured all along

Despair, and never failed.

-From "To My Verses" (1910s)

Translated by Walter Arndt

ANNA AKHMATOVA BELONGS TO the magnificent quartet of Russian poets whose fellow members are Osip Mandelstam, Boris Pasternak and Marina Tsvetaeva. Like her fellow poets, Akhmatova suffered a bitter fate. Mandelstam died en route to a labor camp (1938); Tsvetaeva hanged herself (1941); Pasternak, ostensibly the "luckiest" of the four, fell victim to a vicious campaign after the publication of Doctor Zhivago, followed by the Nobel Prize for Literature, and in the midst of unbearable pressures died at home in 1960. After the brilliant success of her first books, Akhmatova was forcibly silenced in the mid-1920s and was unable to publish any verse until 1940. But the rehabilitation was short-lived. In August 1946, the Central Committee passed a resolution (rescinded only in 1988) that condemned the "half-nun, half-harlot" Akhmatova, along with Mikhail Zoshchenko, one of the most remarkable satirists of the time. It was only in the 1960s that Akhmatova began to receive the homage due her.

AA thuộc bộ tứ thần sầu những nhà thơ Nga, và số phận, cũng bi thảm như họ. Mandelstam chết trên đường tới trại lao động khổ sai. Tsvetaeva treo cổ tự tử. Pat, may mắn nhất, nhưng cũng bị chửi rủa thê thảm nhất, sau khi được Nobel, và chết tại gia. Sau khi nổi tiếng với tập thơ đầu, Bà bị bắt buộc phải im tiếng, giữa thập niên 1920, tới 1940 mới lại được in thơ, nhưng chẳng được lâu. Bà được nhà nước Xô Viết ra hẳn 1 nghị quyết, cấm tiệt in ấn mọi cái viết, sự xuất hiện của con mụ “nửa nữ tu, nửa gái điếm”, và phải đến thập niên 1960 Bà mới được thanh thản.

Bài viết của Brodsky về Anna Akhmatova cực kỳ quan trọng, ở điểm, nhìn ra được vị trí cực kỳ quan trọng của Bà, trong dòng lịch sử văn học của toàn thể nước Nga, suốt từ thời dựng nước.

Bà, phải nói, không ưa nhân dân Nga, không ưa chế độ, nhưng không hề bỏ đi.

Tin Văn sẽ đi bài này, as always.

Lịch sử Nga là một lịch sử của đau khổ và nhục nhã gần như không làm sao hiểu được, hay, chấp nhận được. Nhưng cả hai - quằn quại vì đau khổ, và ô nhục vì hèn hạ - nuôi dưỡng những cội rễ một viễn ảnh thiên sứ, một cảm quan về một cái gì độc nhất vô nhị, hay là sự phán quyết sáng ngời. Cảm quan này có thể chuyển dịch vào một thành ngữ “the Orthodox Slavophile”, với niềm tin của nó, là, Nga là một xứ sở thiêng liêng theo một nghĩa thật là cụ thể, chỉ có nó, không thể có 1 xứ nào khác, sẽ nhận được những bước chân đầu tiên của Chúa Ky Tô, khi Người trở lại với trần gian.

Joseph Brodsky cũng nhận ra điều này, ở thơ của Anna Akhmatova:

The degree of compassion with which the various voices of this "Requiem" are rendered can be explained only by the author's Orthodox faith; the degree of understanding and forgiveness which accounts for this work's piercing, almost unbearable lyricism, only by the uniqueness of her heart, her self and this self's sense of Time. No creed would help to understand, much less forgive, let alone survive this double widowhood at the hands of the regime, this fate of her son, these forty years of being silenced and ostracized. No Anna Gorenko would be able to take it. Anna Akhmatova did, and it's as though she knew what there was in store when she took this pen name.

At certain periods of history it is only poetry that is capable of dealing with reality by condensing it into something graspable, something that otherwise couldn't be retained by the mind. In that sense, the whole nation took up the pen name of Akhmatova-which explains her popularity and which, more importantly enabled her to speak for the nation as well as to tell it something it didn't know. She was, essentially, a poet of human ties: cherished, strained, severed. She showed these evolutions first through the prism of the individual heart, then through the prism of history, such as it was. This is about as much as one gets in the way of optics anyway.

These two perspectives were brought into sharp focus through prosody which is simply a repository of Time within language. Hence, by the way, her ability to forgive-because forgiveness is not a virtue postulated by creed but a property of time in both its mundane and metaphysical senses. This is also why her verses are to survive whether published or not: because of the prosody, because they are charged with time in both said senses. They will survive because language is older than state and because prosody always survives history. In fact, it hardly needs history; all it needs is a poet, and Akhmatova was just that.

-JOSEPH BRODSKY

1957

Mùa Hè năm đó Paris kỷ niệm lần thứ 100 phá ngục Bastille – 1889.

Lễ hội cổ xưa St. John’s Eve thì vào đêm tôi sinh ra đời, và vẫn là như thế, 23 Tháng Sáu.

Tên tôi, là để vinh danh bà ngoại tôi, Anna Yegorovna Motovilova. Mẹ của bà, dòng dõi Hốt Tất Liệt, công chúa Hung Nô, Akhmatova. Tên của bà, tôi lấy làm bút hiệu, không biết rằng thì là mình sẽ trở thành thi sĩ Nga [bà khiêm tốn, đúng ra, trở thành nữ thần thi ca Nga, một nữ thần sầu muộn, như Brodsky vinh danh bà.]

Tôi sinh ra tại dacha Sarakina, gần Odessa. Cái dacha này thì cũng chẳng khác chi một túp lều ở cuối 1 dải đất hẹp chạm biển. Bãi biển có bực đi xuống.

Khi tôi 15 tuổi, có lần dạo chơi, tới túp lều. Tới lối vô, tôi nói bâng quơ, sau này người ta sẽ khắc 1 tấm biển, ghi lại cái ngày mà tôi tới đây.

Mẹ tôi, nhìn tôi, lắc đầu, không biết tao nuôi nấng mi tệ hại ra sao, mà nên nông nỗi này!

Earthly fame's like smoke, I guess-

It's not what I asked for from those above.

I brought so much luck and happiness

To all the men I blessed with love.

One's alive even at this date,

Mad for a girlfriend he met somewhere.

The other turned bronze and stands in wait

Covered with snow, in the village square.

1914

Anna Akhmatova

Danh vọng trần thế thì như khói, tôi nghĩ thế -

Thứ đó, tôi không đòi, từ những đấng ở bên trên kia

Tôi đem đến quá nhiều may mắn và hạnh phúc

Cho tất cả những người đàn ông mà tôi ban phước tình yêu

Một người thì còn sống, vào thời điểm này,

Khùng, vì 1 cô bạn mà anh ta gặp ở đâu đó

Còn người kia thì biến thành đồng và đứng đợi,

tuyết phủ đầy người

ở quảng truờng làng

1914

I am now working on the commentary for the third volume of the Academy edition of Pushkin's works (The Golden Cockerel). This work consumes almost all my time and has postponed the realization of other projects.

I have devoted a lot of time to translation. Recently The Star printed my translation of a long poem by the Armenian poet Daniel Vorouzhan-"First Sin". I have just completed the translation of two poems by the contemporary Armenian poet, Charents.

Apart from this, I translated into Russian all the French poetry printed in the commentary to the first volume of the Academy edition of Pushkin's works, in addition to Pushkin's French poems.

I have been writing lyric poetry. I have prepared for publication my Selected Works (for the Soviet Writer Publishing House), which includes not only previously published poems from all of my books, but also poems written during the period 1930-1935.

I follow Soviet poetry. Among contemporary poets I value and esteem B. Pasternak. I recently wrote a poem that is dedicated to him. This is the final stanza of that poem:"

He was rewarded with an eternal childhood,

His penetrating eye and generosity beamed,

And all the earth was his inheritance

And he shared with all men

He who compared himself to the eye of a horse,

Glances, looks, sees, recognizes,

And puddles shine like molten diamonds, of course,

And any ice is lost in surmises.

In the purple mist, unvisited streets unwind,

A station, logs, leaves, doves.

Train whistles, the crunch of watermelon rind,

Shy hands in perfumed suede gloves.

Rumbles, clangs, screeches, reach high tide

And die. This means he's coming: he carefully places

Each foot on pine needles, tries as he's always tried

Not to frighten the light sleep of empty spaces.

This means he's counting grains, keeping a tab

On empty ears of wheat, that he came back,

Again, from someone's funeral to the slab

In the Daryal wilds, which is also accursed and black.

Languor again burns the Moscovian loam,

In the distance, deadly bells jingle. Do you know

Who's gotten lost not even a stone's throw from home,

Where everything ends and you're up to your waist in

snow?

Because he compared smoke to the Laocoon,

And celebrated thistles in graveyard places,

Because he filled worlds with new ringing and so on

In reflected stanzas original spaces-

He's been rewarded with a kind of eternal childhood,

His keen sight and generosity shine like the sun,

The earth was his inheritance, plain and wildwood,

And he shared it with everyone.

1936

Late at night. Monday. The twenty-third.

The capital's outlines in the mists.

Some idiot's given us the word,

He's informed the world that love exists.

And out of boredom or laziness

Everyone believes and lives that way:

They all look forward to trysts, no less,

They sing their love songs night and day.

But to some, the secret's revealed,

The smallest silence weighs like a brick.

I too stumbled on what was concealed.

Since then I've felt as if I was sick.

1917

As for saying goodbye, we don't know how,

Shoulder to shoulder we keep on walking.

Its getting darker and darker now,

You are pensive, and I'm not talking.

We enter a church-Inside they believe

In funerals, christenings, weddings too,

Without looking at each other, we leave.

Why is everything different between me and you?

Or else we sit in trampled snow

In a cemetery and begin to sigh,

You take a stick and draw the chateau,

Where we'll always be, just you and 1.

1917

You invented me. No such person exists, that's for sure,

There's no such creature anywhere in sight.

No poet can quench my thirst, no physician has a cure,

The shadow of your ghost haunts me day and night.

We met in an unbelievable year,

The energies of the world were worn through,

The world was in mourning, everything sagged with

fear,

And only the graves were new.

In the absence of light, how black the Neva grew,

The deaf night surrounded us like a wall . . .

That's exactly when I called out to you!

What I was doing-I didn't yet understand at all.

And, as if led by a star you came to me,

As if walking on a carpet the tragic autumn had grown,

Into that house ravaged for the rest of eternity,

From whence a flock of burned verses has flown.

1956

Mi phịa ra ta. Làm gì có cô gái nào tên là BHD, chắc chắn như thế,

Làm gì có thứ bông hoa lạ như thế ở khắp mọi nơi, trong tầm nhìn

Chẳng tên thi sĩ nào có thể làm dịu cơn khát của ta, không tên y sĩ nào có thứ thần dược chữa trị,

Cái bóng của con ma tình, là mi, tên GCC, làm khổ ta ngày và đêm

Hai đứa ta gặp nhau đúng trong cái năm không thể nào tin tưởng được đó

Nhiệt tình trọn thế gian đốt trọn cuốn lịch

Thế giới ư, tóc tang tang tóc, mọi chuyện chùng xuống vì sợ hãi

Chỉ những nấm mồ là mới.

Thiếu vắng ánh sáng, con sông Neva bèn càng đen thui

Đêm điếc đặc bao quanh đôi ta như bức tường

Đúng là vào lúc như thế ta gào tên mi, GCC!

Ta đang làm gì đây - Ta chẳng thể nào hiểu

Và, như thể được 1 vì sao dẫn dắt,

Mi bèn đến với ta....

Selected and Translated by Lyn Coffin

INTRODUCTION

Note: Bài Intro, sau được in trong tập tiểu luận, với cái tên Nữ Thần Thi Ca Sầu Muộn, The Kneeling Muse

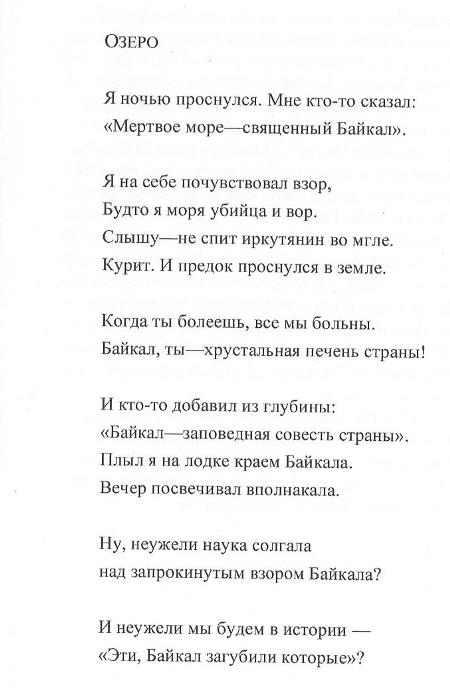

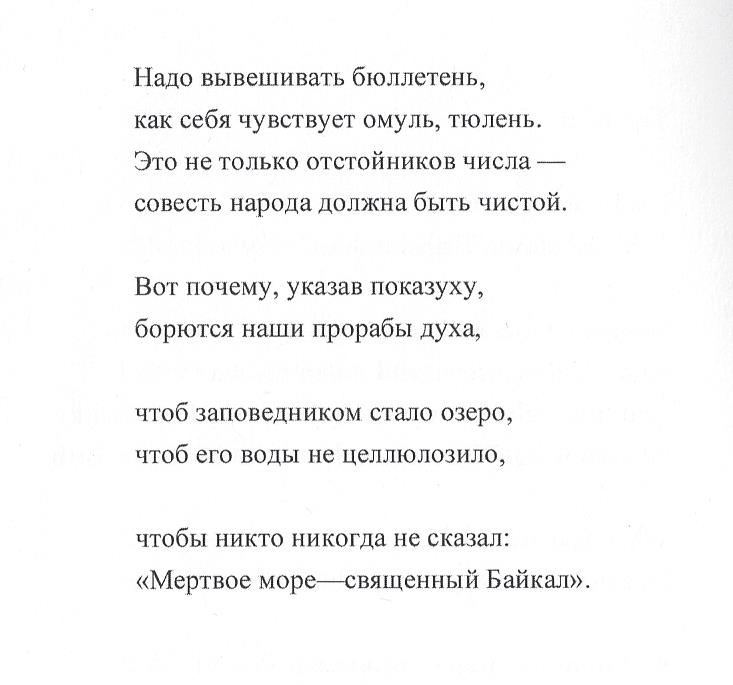

Hồ Baikal – Andrei Voznesensky

Một bài thơ được đặt hàng dịch, có thể do nó phù hợp

với tình hình nóng bỏng hiện giờ chăng? Cá nhân mình thì không

thích bài thơ này lắm, nhưng chả hiểu sao vẫn dịch được

The lake

I woke at night. Some said:

"The sea of holy Baikal

is dead."

Someone's eyes are

on me.

As if I had murdered

and stolen the sea.

And hear-the Irkutskian

is wide awake in the dark.

He's smoking. The

ancestor has wakened in the earth.

When you are sick,

we are sick.

Baikal, the country's

crystal liver!

And from the deep

someone added:

"Baikal, the inner

eye of our world."

I drifted in a boat

along the Baikal shore.

Evening had a lustre.

So, did science actually

tell lies

Before the unflinching

eye of Baikal?

And will we really

be known as-

"Those who wrecked

Baikal"?

We must send out a

bulletin,

About how salmon and

seal feel.

It's not only the

increasing sediment-

The country's conscience

has got to be cleared.

This is why, as they

ferret out the flim-flam,

Dancers expert in

diatribe vs dialogue wrestle

To preserve the lake

as a reserve,

So its waters won't

turn to cellulose,

So no one will ever

say:

"The sea of holy Baikal

is comatose."

| ОЗЕРО

Андрей Вознесенский Я ночью проснулся. Мне кто-то сказал: |

HỒ

Andrei Voznesensky Tỉnh giấc giữa đêm. Có người bảo tôi: |

Tks Both of U

NQT

I woke at night. Some said:

"The sea of holy Baikal is dead."

Someone's eyes are on me.

As if I had murdered and stolen the sea.

And hear-the Irkutskian is wide awake in the dark.

He's smoking. The ancestor has wakened in the earth.

When you are sick, we are sick.

Baikal, the country's crystal liver!

And from the deep someone added:

"Baikal, the inner eye of our world."

I drifted in a boat along the Baikal shore.

Evening had a lustre.

So, did science actually tell lies

Before the unflinching eye of Baikal?

And will we really be known as-

"Those who wrecked Baikal"?

We must send out a bulletin,

About how salmon and seal feel.

It's not only the increasing sediment-

The country's conscience has got to be cleared.

This is why, as they ferret out the flim-flam,

Dancers expert in diatribe vs dialogue wrestle

To preserve the lake as a reserve,

So its waters won't turn to cellulose,

So no one will ever say:

"The sea of holy Baikal is comatose."

Penguin Russian Poetry

Akhmatova: Nửa Thế Kỷ Của Tôi

1957

Mùa Hè năm đó Paris kỷ niệm lần thứ 100 phá ngục Bastille – 1889.

Lễ hội cổ xưa St. John’s Eve thì vào đêm tôi sinh ra đời, và vẫn là như thế, 23 Tháng Sáu.

Tên tôi, là để vinh danh bà ngoại tôi, Anna Yegorovna Motovilova. Mẹ của bà, dòng dõi Hốt Tất Liệt, công chúa Hung Nô, Akhmatova. Tên của bà, tôi lấy làm bút hiệu, không biết rằng thì là mình sẽ trở thành thi sĩ Nga [bà khiêm tốn, đúng ra, trở thành nữ thần thi ca Nga, một nữ thần sầu muộn, như Brodsky vinh danh bà.]

Tôi sinh ra tại dacha Sarakina, gần Odessa. Cái dacha này thì cũng chẳng khác chi một túp lều ở cuối 1 dải đất hẹp chạm biển. Bãi biển có bực đi xuống.

Khi tôi 15 tuổi, có lần dạo chơi, tới túp lều. Tới lối vô, tôi nói bâng quơ, sau này người ta sẽ khắc 1 tấm biển, ghi lại cái ngày mà tôi tới đây.

Mẹ tôi, nhìn tôi, lắc đầu, không biết tao nuôi nấng mi tệ hại ra sao, mà nên nông nỗi này!

Give me illness for years on end,

Shortness of breath, insomnia, fever.

Take away my child and friend,

The gift of song, my last believer.

I pray according to Your rite,

After many wearisome days,-

That the storm cloud over Russia might

Turn white and bask in a glory of rays.

1915

Translated by Lyn Coffin

SONG ABOUT SONGS

It will burn you at the start,

As if to breezes you were bare,

Then drop deep into your heart

Like a single salty tear.

And a heart full of spite

Will come to know regret.

And this sorrow, although light,

It will not forget.

Others will reap. I only sow.

Of course! When the triumphant horde

Of scythers lays the grain low,

Bless them, O Lord!

And so that I may lift

My eyes in thanks to You above,

Let me give the world a gift

More incorruptible than love.

1916

AkhmatovaBài Ca về Những Bài Ca

Nó

sẽ đốt cháy bạn lúc thoạt đầu

Như thể bạn trần truồng trước những làn gió

Rồi thọi 1 cú thật sâu, ngay tim bạn

Như 1 giọt nước, mặn, cực mặn, chỉ 1 giọt

Và

trái tim đầy thù oán

Sẽ biết như thế nào là, chưa đi mưa chưa biết lạnh

Chưa thấy quan tài chưa đổ lệ,

Nghĩa là, biết, ân hận

Và nỗi ân hận, mặc dù nhẹ nhàng

Sẽ chẳng thể nào quên

Những

kẻ khác, thu hoạch

Tôi, chỉ gieo.

Lẽ tất nhiên! Khi bầy người cầm hái chiến thắng

Để hạt xuống

Hãy chúc phúc cho họ, ôi Chúa

Cám ơn Người ở trên cao

Hãy để cho tôi ban cho đời

Một món quà

Không thối rữa, hơn nhiều

So với tình yêu.

It seems that the voice we humans

own

Will never sound, never celebrate,

Only a wind from the age of stone

Keeps on knocking at the black gate.

And it seems to me that under the sun

I alone remain-this honor's mine,

Simply because I was the first

Who wanted to drink the deadly wine.

1917

Có vẻ như cái thứ tiếng người mà chúng ta có đó

Nó sẽ chẳng bao giờ kêu lên

Chẳng bao giờ ăn mừng

Chỉ là tiếng gió từ thời kỳ đồ đá

Liên tục gõ lên chiếc cổng đen

Và hình như chỉ còn tôi, đơn độc dưới ánh mặt trời

Và đây là niềm vinh quang của tôi

Giản dị, ấy là vì tôi là người đầu tiên

Muốn uống ly rượu độc

ALTHOUGH PUSHKIN THOUGHT OF himself least of all as a "children's writer," the term that is now commonly accepted (when Pushkin was asked to write something for children, he flew into a rage ...) although his fairy tales were certainly not intended for children and the famous introduction to Ruslan was not addressed to a child's imagination either, the fates have decreed that his works be destined to serve as a bridge between Russia's great genius and children.

We have all heard innumerable times three-year-old performers recite "the learned cat" and "the weaver and the cook'? and have seen how the child's little pink finger points to the portrait in the child's book-and he is called "Uncle Pushkin."

Everyone knows and loves Yershov's The Little Humpback Horst', too.' However, I've never heard "Uncle Yershov."

There is not and has never been a single Russian-speaking family in which the children could remember when they first heard that name and saw that portrait. Pushkin's poetry bestows to children the Russian language in all its splendor, a language they perhaps will never hear again and will never speak, but which, nevertheless, will be with them like an eternal treasure.

During the anniversary days of 1937, the appropriate commission resolved to remove the Pushkin monument, which had been erected in a darkish square in a part of the city that did not even exist in Pushkin's time, and place it on Leningrad' Pushkin Street. They dispatched a freight crane -in general everything required in such situations. But something unprecedented took place: the children who were playing by the monument in the square raised such a howl that they were forced to telephone the commission to ask what should be done. The answer: "Let them have their monument"-and the truck left empty.

One can say with absolute certainty that at that difficult time a good half of those children had lost their fathers (and many their mothers as well), but they considered it their sacred duty to protect Pushkin.

Mặc dù Pushkin ít nghĩ về mình như “nhà văn của ‘tủi’ thơ”, nhưng cái “nick” này thường được gán cho ông, (khi, lỡ có ai “order” ông, cho tui 1 cái vé đi “tủi thơ” đi, ông gần như phát khùng); mặc dù những câu chuyện cổ tích của ông thực tình không nhắm tới độc giả con nít, và cái bài giới thiệu nổi tiếng cho "Ruslan" thì cũng không mắc mớ gì tới trí tưởng tượng của 1 đứa trẻ, nhưng, những số mệnh bèn ra lệnh, tác phẩm của mi [Pushkin] là cái cầu giữa thiên tài lớn lao của Nga, và những đứa trẻ.

Many of the houses were painted red (like the Winter Palace), crimson, and rose. There weren't any of these beige and gray colors that now run together so depressingly with the frosty steam or the Leningrad twilight.

There were still a lot of magnificent wooden buildings then (the houses of the nobility) on Kamennoostrovsky Prospect and around Tsarskoe Selo Station. They were torn down for firewood in 1919. Even better were the eighteenth-century two-story houses, some of which had been designed by great architects. "They met a cruel fate"-they were renovated in the 1920s. On the other hand, there was almost no greenery in Petersburg of the 1890s. When my mother came to visit me for the last time in 1927, she, along with her reminiscences of the People's Will, unconsciously recalled Petersburg not of the 1890s, but of the 1870s (her youth), and she couldn't get over the amount of greenery. And that was only the beginning! In the nineteenth century there was nothing but granite and water.

THE WILLOW

And a decrepit bunch of trees.

Pushkin

I grew up where all was patterned

and silent,

In the cool nursery of the age, itself young;

I didn't like human words, spoken or sung,

But I understood what the wind meant.

I liked burdock and nettles but the willow tree,

The silver willow, I liked especially.

It lived gratefully with me till now

And with its weeping branches seemed

To make dreamlessness like something dreamed.

It's hard to believe I outlived it somehow.

There's a stump. And in alien tongues, other willows

will

Be saying whatever it is they say

Under our skies, under theirs. I'm completely still.

It's as if my brother had died today.

1940

Anna Akhmatova

Liễu

Và một nhúm cây già

Pushkin

Tôi lớn lên khi tất cả đều tỏ

ra gương mẫu và im lặng

Trong cái thời đại mát mẻ của vườn ươm cây, chính nó thì cũng trẻ

măng;

Tôi không ưa tiếng người, nói cũng thế, mà hát thì lại càng chính

thế;

Nhưng tôi hiểu, gió nghĩa là gì.

Tôi mê burdock, tầm ma, nhưng đặc biệt, liễu, cực mê liễu bạc

Tôi sống thật biết ơn cùng với nó cho tới bây giờ

Và với những nhánh liễu rưng rưng, thì một điều gì không mơ mộng

cũng trở thành mộng mơ

Thật khó mà tin được tôi sống dai hơn nó, cho tới lúc này.

Một cái gốc cây. Và trong những âm điệu ngoại lai, những loài liễu

khác sẽ nói bất cứ điều gì chúng nói

Dưới bầu trời của chúng ta, dưới bầu trời của chúng.

Tôi nín thinh.

Như thể người anh của tôi mất bữa nay.

….

Naturally enough, poems of this sort couldn't be published, nor could they even be written down or retyped. They could only be memorized by the author and by some seven other people since she didn't trust her own memory. From time to time, she'd meet a person privately and would ask him or her to recite quietly this or that selection as a means of inventory. This precaution was far from being excessive: people would disappear forever for smaller things than a piece of paper with a few lines on it. Besides, she feared not so much for her own life as for her son's who was in a camp and whose release she desperately tried to obtain for eighteen years. A little piece of paper with a few lines on it could cost a lot and more to him than to her who could lose only hope and, perhaps, mind.

The days of both, however, would have been numbered had the authorities found her "Requiem," a cycle of poems describing an ordeal of a woman whose son is arrested and who waits under prison walls with a parcel for him and scurries about the thresholds of state's offices to find out about his fate. Now, this time around she was autobiographical indeed, yet the power of "Requiem" lies in the fact that Akhmatova's biography was too common. This Requiem mourns the mourners: mothers losing sons, wives turning widows, sometimes both as was the author's case. This is a tragedy where the choir perishes before the hero.

The degree of compassion with which the various voices of this "Requiem" are rendered can be explained only by the author's Orthodox faith; the degree of understanding and forgiveness which accounts for this work's piercing, almost unbearable lyricism, only by the uniqueness of her heart, herself and this self's sense of Time. No creed would help to understand, much less forgive, let alone survive this double widowhood at the hands of the regime, this fate of her son, these forty years of being silenced and ostracized. No Anna Gorenko would be able to take it. Anna Akhmatova did, and it's as though she knew what there was in store when she took this pen name.

At certain periods of history it is only poetry that is capable of dealing with reality by condensing it into something graspable, something that otherwise couldn't be retained by the mind. In that sense, the whole nation took up the pen name of Akhmatova-which explains her popularity and which, more importantly enabled her to speak for the nation as well as to tell it something it didn't know. She was, essentially, a poet of human ties: cherished, strained, severed. She showed these evolutions first through the prism of the individual heart, then through the prism of history, such as it was. This is about as much as one gets in the way of optics anyway.

These two perspectives were brought into sharp focus through prosody which is simply a repository of Time within language. Hence, by the way, her ability to forgive-because forgiveness is not a virtue postulated by creed but a property of time in both its mundane and metaphysical senses. This is also why her verses are to survive whether published or not: because of the prosody, because they are charged with time in both said senses. They will survive because language is older than state and because prosody always survives history. In fact, it hardly needs history; all it needs is a poet, and Akhmatova was just that.

-JOSEPH BRODSKY

Strong Words

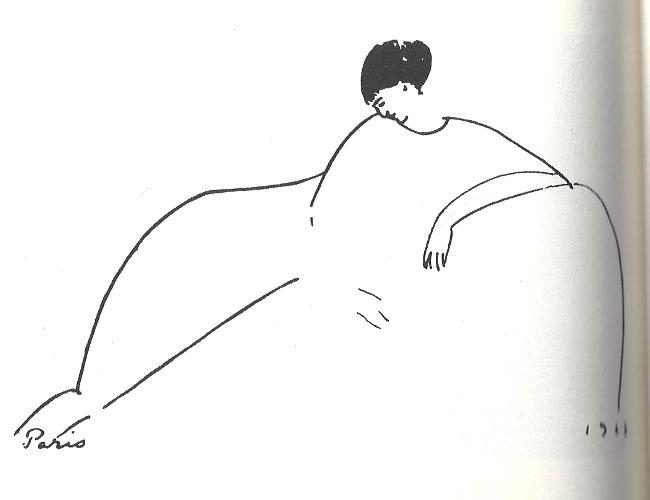

Modigliani

With Modigliani following me

Through a blue Parisian fog

Looking like a dispirited and

Dispiriting shadow of himself,

I've been shaken even in my sleep

By a deep yearning remorse.

Yet for me-his Egyptian woman

...

An old grinder's organ moans

A Paris music that intones underfoot

Like the groaning sea,

He'd imbibed in his shame,

Drunk his fill of grief and hard times.

In St. Petersburg's National Library there is an Akhmatova manuscript, "Poem Without A Hero." In its margins, Akhmatova has written lines to Amedeo Modigliani. Akhmatova never did include this poem among her works. It was not published until 1980.

Modigliani

Với Modigliani theo tôi,

Qua sương mù xanh Paris,

Như bóng ma vất vưởng của chính chàng

Trong đêm khuya,

Tôi rụng rời bị dựng dậy

Bởi chính nỗi niềm ân hận miên man của mình

Tuy nhiên với tôi, người đàn

bà Ai Cập của chàng….

Cây đàn organ của một tay thợ mài già rên rỉ

Một khúc nhạc Paris ngân ngư dưới chân

Như biển lầm bầm

Thấm đậm nỗi tủi hổ

Chàng uống đầy nỗi đau, và cực nhọc.

Chỉ ít lâu sau khi Một ngày trong đời Ivan Denisovich xuất hiện trên Novy mir, Tháng 11, 1962, Kopelev sắp xếp cho Akhmatova và Solz gặp nhau. Đọc tác phẩm đầu tay của nhà văn 43 tuổi, Akhmatova tự hỏi, liệu anh ta đủ mạnh để ứng phó với hoàn cảnh, khi mọi sự chú tâm xoáy vào anh, như bà đã từng, hay gần nhất, Pasternak cũng đã từng, và cảnh cáo, “Anh có biết chỉ trong vòng 1 tháng anh trở thành người nổi tiếng nhất trên thế giới?” “Tôi biết. Nhưng nó không kéo dài." “Anh chịu nổi danh vọng, Can you endure fame?” “Tôi cứng cựa lắm. Tôi chịu nổi trại tù Stalin”. “Pasternak không chịu đựng nổi danh vọng. Thật khó chịu đựng nổi danh vọng, nhất là thứ đến muộn trong đời”. Mặc dù họ kính trọng lẫn nhau, nhưng cuộc gặp gỡ chẳng được thoải mái. Solz, đã từ lâu quen với việc “dím” bản thảo, không thể dễ dàng trưng ra những bản văn xuôi khác của mình, 1 điều sau ông rất hối tiếc, và coi là lầm lỡ. Thay vì vậy, ông cho bà coi thơ của mình, và bà nói thẳng, đừng làm thơ, thứ đó không hợp với nhà văn, là ông. Đến lượt bà, bèn đọc Kinh Cầu, và sau đó, Solz nói với Kopelev:

Một bài thơ hay, lẽ dĩ nhiên Đẹp. Rổn rảng. Nhưng nói cho cùng, cả nước đau khổ, hàng chục triệu con người, và bài thơ thì là về một trường hợp cá nhân, về 1 bà mẹ và đứa con trai… Tôi nói với bà là bổn phận của 1 nhà thơ Nga là viết về những đau khổ của nước Nga, vượt lên khỏi nỗi đau cá nhân, và nói về nỗi đau của cả nước…Bà im lặng, suy nghĩ. Có thể bà không thích tôi nói như thế. Bà quen được thổi. Nhưng, đúng là 1 nhà thơ lớn.

Tất nhiên, Akhmatova đâu quên “hàng chục triệu con người”, như phần epilogue, kết, của Kinh Cầu cho thấy. Nhưng nhận xét của Solz cho thấy sự khác biệt cơ bản về bản tính của hai nhà văn. Lý tưởng nghệ thuật của Solz là về 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết hiện thực lớn lao của thế kỷ 19, thứ tiểu thuyết như được hiểu bởi Tolstoy, và Balzac, và George Eliot, với sự hiểu biết sâu xa của nó, về như thế nào, những sức mạnh xã hội nhào nặn cuộc đời của những cá nhân con người. Ngược hẳn lại, Akhmatova, cơ bản là một nhà thơ trữ tình, với những đề tài chính, là yêu đương, mất mát. Vào những hoàn cảnh thích hợp những đề tài này có thể có mùi, có ý nghĩa xã hội, chính trị: khi quê nhà thân thương của bà bị nguy hiểm; Akhmatova là 1 nhà thơ yêu nước; khi con trai của bà và những người thật thân cận, thật quí giá đối với bà, của bà, bị giựt ra khỏi bà - bị bắt, bị tra tấn, và đôi khi bị giết - những bài thơ sẽ từ những mất mát đó trở thành hành động, chứng tích chống lại những tội ác của nhà nước.

Despite the two writers' mutual admiration, the meeting did not go entirely smoothly, Solzhenitsyn, long accustomed to concealing his writings, could not bring himself to show his other completed prose works to Akhmatova, a mistake he later profoundly regretted. Instead he showed her his poetry, which, as she justly and tactfully noted, was not his strength as a writer. In turn, she recited Requiem to him, and he told Kopelev after,

"A good poem, of course. Beautiful. Sonorous. But after all, a nation suffered, tens of millions, and it's a poem about an individual case, about one mother and son .... I said to her that the duty of a Russian poet is to write about the sufferings of Russia, to rise above personal grief and speak of the nation's grief. ... She was silent, reflecting. Perhaps she didn't like that-she's accustomed to flattery, raptures. But she's a great poet. And a truly great theme. That has to be said."

Certainly Akhmatova had not for often the "tens of millions," as the epilogue of Requiem shows. But Solzhenitsyn's remarks do point to a fundamental difference in the nature of the two writers. Solzhenitsyn's artistic ideal is the great nineteenth-century realist novel, the novel as it was understood by Tolstoy and Balzac and George Eliot, with its profound understanding of how social forces shape and misshape the lives of individuals. Akhmatova, by contrast, was fundamentally a lyric poet, whose most characteristic were love and loss. In appropriate circumstances, these themes could take on social and political meanings: when her beloved homeland was in danger, Akhmatova was a patriotic poet; when her son and other people dear to her were taken from her - arrested, tortured, and sometimes killed-the poems that arose from those losses were acts of witness against state crimes. Unlike Solzhenitsyn, Akhmatova did not set out to become a witness as the result of a historian's resolve to establish the truth, or as an advocate seeking justice for the victims; she became a witness first for her son and then for all the other mothers who suffered as she did. To expect Requiem to "rise above personal grief" is a fundamental misunderstanding of its nature: it is through, not in spite of, the personal that a lyric poet understands the collective.

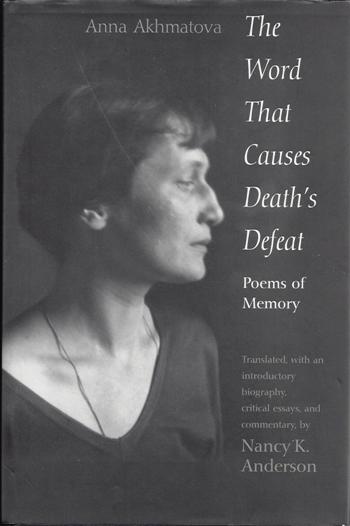

The Word That Causes Death’s Defeat. Late Fame and Final Years

Akhmatova: Nửa Thế Kỷ Của Tôi

Một lời về Pushkin.

Người đi trước tôi, Pavel Shchegolyov,

kết thúc tác phẩm, viết về cuộc tử đấu tay đôi, và cái chết của Pushkin,

với cả lô những suy đoán, về tại sao xã hội và những phát ngôn nhân của

nó, thù hận nhà thơ, và tống xuất ông như ngoại nhân, ra khỏi bọn chúng.

Bây giờ, đã đến lúc phải đặt lại câu hỏi, ông coi lũ chúng nó

là cái khốn kiếp gì, và ông đã làm gì với chúng?

Tôi phải dọn dẹp nhà của tôi.

Ông nói khi chết, bằng tiếng Tẩy:

Il faut que j’arrange

ma maison.

You will not be answerable for

me,

You can sleep peacefully.

Strength is power, but your children

Will curse you for me.

Bạn sẽ không thể trả lời cho

tôi

Bạn có thể an ngủ

Sức mạnh là quyền năng, nhưng con cháu bạn

Sẽ trù ẻo bạn [giùm] cho tôi

[Bạn, ở đây, có thể hiểu như là Nga Xô khốn kiếp, của Pushkin, hay Bắc Kít dã man, của GCC!]

A WORD ABOUT PUSHKIN

My PREDECESSOR, PAVEL SHCHEGOLYOV, (1) concludes his work on Pushkin's duel and death with a series of speculations about why society and its spokesmen hated the poet and expelled him as an alien being from its midst. It is now time to turn this question around and speak aloud not about what they did to him, but what he did to them.

After an ocean of filth, deceit, lies, the complacency of friends and the plain foolishness of the Poletikas and non-Poletikas, (2) the Stroganov clan (3) the idiot horse- guardsmen, who made the d'Anthes affair une affaire de régiment (a question of the regiment's honor), the sanctimonious salons of the Nesselrodes, et al., (4) the Imperial Court, which peeked through every keyhole, the majestic secret advisors-members of the State Council-who had felt no shame at placing the great poet under secret surveillance- after all of this, how exhilarating and wonderful it is to see the prim, heartless ("swinish" as Alexander Sergeyevich himself put it) and, to be sure, illiterate Petersburg watch as thousands of people, upon hearing the fateful news, rushed to the poet's house and remained there forever with all of Russia.

"Il faut que j'arrange ma maison (I must put my house in order)," said the dying Pushkin.

In two days' time his house became a sacred place for his Homeland, and the world has never seen a more complete or more resplendent victory.

Little by little, the entire era (not without reluctance, of course) came to be called the Pushkin era. All the beauties, ladies-in-waiting, mistresses of the salons, Dames of the Order of St. Catherine, members of the Imperial Court, ministers, aides- de-camp and non-aides-de- camp, gradually came to be called Pushkin's contemporaries, and were later simply laid to rest in card catalogues and name indices (with garbled birth and death dates) to Pushkin's works. He conquered both time and space. People say: the Pushkin era, Pushkin's Petersburg. And there is no longer any direct bearing on literature; it is something else entirely. In the palace halls where they danced and gossiped about the poet, his portraits now hang and his books are on view, while their pale shadows have been banished from there forever. And their magnificent palaces and residences are described by whether Pushkin was ever there or not. Nobody is interested in anything else. The Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich in his white breeches looks very majestic on the wall in the Pushkin Museum; manuscripts, diaries, and letters are valuable if the magic word "Pushkin" is there. And, the most terrifying thing for them is what they could have heard from the poet:

You will not be answerable for

me,

You can sleep peacefully.

Strength is power, but your children

Will curse you for me.

And in vain do people believe that scores of handcrafted monuments can replace that one aere perennius (stronger than bronze) not made by hand.(5)

May 26,1961

Komarovo

Translated by Ronald Meyer

The Wild Girl

A PAGAN CHILDHOOD. IN the neighborhood of that dacha (Joy, Streletsky Bay, Khersones) I was nicknamed the "wild girl," because I went barefooted, walked around without a hat, jumped off the boat in the open sea, swam when it was storming, and sunbathed until my skin peeled. And all this shocked the provincial young ladies of Sevastopol.

*

I wrote my first poem when I was eleven years old (it was terrible), but even before that my father for some reason called me a "decadent poetess".... Because my family had moved to the South, I did not graduate from the Tsarskoe Selo School, but the Kiev (Fundukleyevskaya) School, where I studied for all of one year. Then I studied for two years at the Kiev Women's College .... All this time (with rather long breaks) I continued to write poetry and for some unknown reason numbered each poem. Just for fun I can report that judging from the surviving manuscript, "Song of the Last Encounter" was my two hundredth poem."

Pages from a Diary

*

What makes our century the worse?

Has it, dazed with grief and fear,

Touched the blackest sore of all,

Yet not had strength enough to heal?

Điều gì làm thế kỷ của chúng

ta, thế kỷ tệ hại?

Choáng váng đến mê mụ vì đau thương và sợ hãi

Trúng một đòn, đen thủi thùi thui, trong tất cả mọi đòn

Tuy nhiên, đếch có đủ sức mạnh để mà chữa lành?

Volkov: Bên dưới bài thơ thấy ghi 1911, lẽ dĩ nhiên. Sự thực, thực khó mà biết bài thơ được viết ra khi nào. Ngôn ngữ, văn phong cho thấy, nó đếch cần đến 1 sự khai triển nào có ý nghĩa. Bài thơ là cho mọi thời.

This is a language and style that in general does not undergo significant development. It's for all time.

Akhmatova: Nửa Thế Kỷ Của Tôi

Robert Hass, trong bài viết “gia

đình và nhà tù, families and prisons” in trong “What light can do”, nhắc

tới Mandelstam, ông cảm thấy khó chịu, về cái sự bị hớp hồn của chúng ta

đối với nhà thơ, vì vài lý do, but I am uneasy by our fascination with him

for a couple of reasons.

Thứ nhất, là sự nghi ngờ, có thể cái sự tuẫn nạn của ông gãi ngứa

chúng ta, the first is the suspicion that our fascination exists because

his martyrdom flatter us.

Và ông đưa ra 1 nhận định cũng thật thú: Có 1 số nhà thơ có tài,

nhưng vì 1 lý do nào đó, thiếu can đảm, và có những đấng đếch có tài,

nhưng lại quá thừa can đảm.

Nhân đó, ông lèm bèm tiếp về Akhmatova. Cũng theo cách nhận thức

như vậy.

Theo GCC, Robert Hass không đọc

được, cả hai nhà thơ trên. Lý do, theo Gấu vẫn là, có 1 cái gì đó thiếu, về

mặt độc ác, tính ác, ở những nhà thơ Mẽo như ông, cho nên không đọc ra được

những nhà văn nhà thơ của phần đất Á Châu, như Mandelstam, Akhmatova.

Đẩy quá lên bước nữa, có thứ văn chương chúng ta đếch cần đọc,

vì chẳng bao giờ nó ngó ngàng đến cái độc, cái ác của con người, nhất

là Cái Ác Á Châu, trong có Mít.

VII

The word landed with a stony

thud

Onto my still-beating breast.

Nevermind, I was prepared,

I will manage with the rest.

I have a lot of work to do today;

I need to slaughter memory,

Turn my living soul to stone

Then teach myself to live again…

But how. The hot summer rustles

Like a carnival outside my window;

I have long had this premonition

Of a bright day and a deserted house.

Bản án

Như 1 cục đá

Rớt xuống ngực tôi, còn đập

Cũng chẳng sao. Tôi đã được sửa soạn

Và sẽ xoay sở với hồi kết cục

Tôi có khá nhiều việc để làm

bữa nay

Tôi cần tàn sát hồi ức,

Biến hồn mình thành đá

Và dạy cho chính mình,

Lại sống….

Nhưng làm sao.

Mùa hè nóng xào xạc

Như 1 ngày hội ở bên ngoài cửa sổ phòng tôi

Tôi dự cảm điều này lâu rồi

Về một ngày sáng rỡ và một căn nhà bỏ hoang

~ Anna Akhmatova

excerpt from Requiem,

taken from The Complete Poems

with thanks to journal of a nobody Akhmatova: Nửa Thế Kỷ Của Tôi

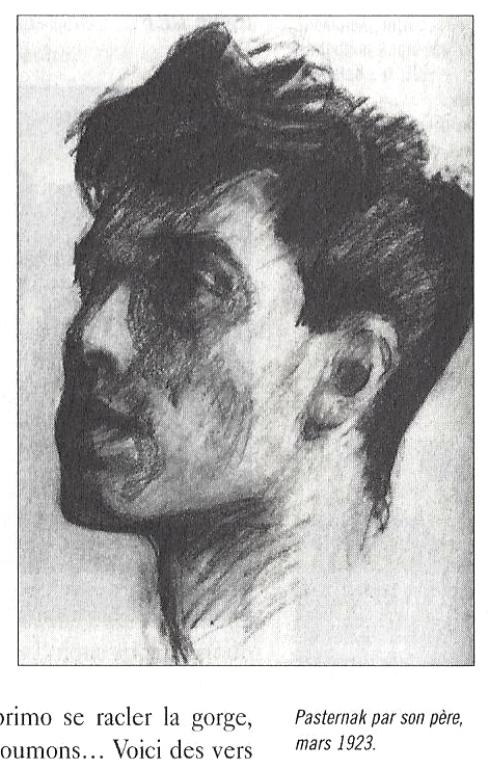

11 juin [1960]. De l'hôpital Botkine, Anna Akhmatova écrit à la mémoire de Pasternak:

Oedipe aveuglé guidé par sa fille,

La muse l'a conduit jusqu'à sa mort.

Un tilleul fou, auprès de ma fenêtre

A fleuri seul en ce mai de douleur,

Juste à l'endroit où il m’avait confié

Qu'il voyait serpenter devant ses yeux

Un sentier d'or aux ailes déployées

Où le gardait la volonté des cieux

Traduction Michel Aucouturier,

Revue des Belles-Lettres,

mars 1996.

Source: Pasternak, éd Quarto Gallimard [NQT]

TO THE MEMORY OF A POET

Like a bird, echo will answer me.

B.P. (Boris Pasternak)

1.

That singular voice has stopped:

silence is complete,

And the one who spoke with forests has left us behind.

He turned himself into a life-giving stalk of wheat

Or the fine rain his songs can call to mind.

And all the flowers that hold this world in debt

Have come into bloom, come forward to meet this

death.

But everything stood still on the planet

Which bears the unassuming name ... the Earth.

2.

Like the daughter of Oedipus

the blind,

Toward death the Muse was leading the seer.

And one linden tree, out of its mind,

Was blooming that mournful May, near

The window where he told me one time

That before him rose a golden hill,

With a winged road that he would climb,

Protected by the highest will.

1960

Boris Pasternak: 1890-1960, renowned Russian poet and novelist.

Source: Anna Akhmatova, Poems, selected and translated by Lyn Coffin [NQT]Oedipe mù, được cô con gái dẫn dắt

Nữ thần thi ca đưa anh tới cái chết của mình

Một bông hoa đoan, khùng, độc nhất,

Nở, vào đúng Tháng Năm đau buồn đó

Ở gần cửa sổ

Nơi ông đã có lần tâm sự cùng tôi

Ông nhìn thấy dựng lên một cảnh đồi vàng

Cùng con đường dốc có cánh

Và ông trèo lên

Được bảo vệ bởi Thánh Ý.

Akhmatova: Nửa Thế Kỷ Của Tôi

Life is for others, not for you,

Cold in the snow you lie,

Bayonets made twenty-eight wounds,

Bullets-another five.

A garment of new grief I made,

I sewed it for my love.

Oh Russian earth, it loves the taste,

It loves the taste of blood.

Tuyết lạnh anh nằm

Lưỡi lê anh lãnh: hai mươi tám mũi

Cộng thêm năm vết đạn

Tấm áo, nỗi đau mới,

Tôi may nó cho tình tôi.

Ôi đất Nga ơi, mi yêu mùi vị,

Của máu

It was not, however, as a research

editor or a memoirist but as a poet that Akhmatova gave her most immediate,

personal response to the deaths of Gumilyov and Blok and the destruction

of the world of her youth. After the virtual silence of 1920, Akhmatova wrote

some thirty-four poems in 1921, eleven of which are specifically dated

August 1921. These poems are filled with images of bitter and irreversible

separation, violence, and death. They reflect not only Akhmatova's personal

agony, but the agony of her country. Thus in one lyric of eight simple and

devastating lines she uses traditional folk diction and imagery to evoke

the lament of a Russian peasant Everywoman.

The Word That Causes Death’s Defeat: Poems of

Memory

Nancy K. Anderson dịch, giới thiệu, chú giải…

Chẳng phải biên

tập viên nghiên cứu, hay tưởng niệm, hồi ức gia, nhưng, như nhà thơ, Akhmatova

đã đưa ra một ứng đáp nóng hổi nhất, riêng tư nhất, trước những cái chết

của Gumilyov và Blok và sự huỷ diệt thế giới tuổi

trẻ của bà. Sau sự im lặng giả đò, ảo, của năm 1920, liền năm sau, 1921,

bà cho ra lò 34 bài thơ, 11 bài trong đó cho biết rõ thời điểm sáng tác:

Tháng Tám 1921; chất chứa trong chúng là những hình ảnh cay đắng, chia ly

bất phản hồi, hung bạo, và cái chết. Chúng phản ảnh không chỉ cơn hấp hối

của cá nhân nhà thơ, mà còn của xứ sở của bà.

Đọc Bi Khúc của Liu Xiaobo, GCC nhớ tới Akhamatova,

nhớ tới “Cái Từ Đuổi Thần Chết Chạy Có Cờ”.

Anna Akhmatova qua nét vẽ David

Levine, NYRB

Được chụp hình, được họa nhiều nhất, trong các thi sĩ.

Nhìn nghiêng, chỉ cần nhìn cái mũi, là nhận ngay ra Bà.

Ở vào một vài giai đoạn của lịch

sử, chỉ có thơ mới có thể chơi ngang ngửa với thực tại, bằng cách nhét chặt

nó vào một cái gì mà nhân loại có thể nâng niu, hoặc giấu diếm, ở trong lòng

bàn tay, một khi cái đầu chịu thua không thể nắm bắt được."

"Theo nghĩa đó, cả thế giới nâng niu bút hiệu Anna Akhmatova."

Joseph Brodsky

"Tôi

mang cái chết đến cho những người thân của tôi

Hết người này tới người kia gục xuống.

Ôi đau đớn làm sao! Những nấm mồ

Đã được tôi báo trước bằng lời."

"I brought on death to my dear

ones

And they died one after another.

O my grief! Those graves

Were foretold by my word." (1)

.

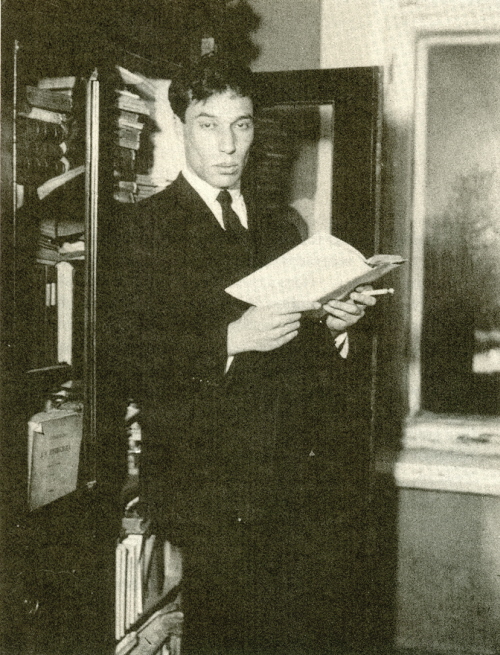

Pasternak's poems are like the

flash of a strobe light-for an instant they reveal a corner of the universe

not visible to the naked eye. I fell in love with these poems as a child.

They were magical, fragments of the natural world captured in words that

I did not always understand. Pasternak was my father's favorite poet. In

the evenings he often recited his poems aloud, as did Marina Tsvetayeva,

a friend of the family who often came to our house in those years before

the war.

Long afterwards, George Plimpton and Harold Humes brought the live

Pasternak into my life. A year or so after the resounding success of

Doctor Zhivago, when

the dust had begun to settle on the scandal of his being forced to give

up the Nobel Prize, they sent me on a mission to Moscow to interview the

poet for The Paris Review.

I'll never forget that sunny day at Peredelkino in the winter of

1959-1960, a few months before Pasternak died. The sparkling snow, the

fir trees, the half torn note pinned to the door on the veranda at the

side of the house: "I am working now. I cannot receive anybody. Please

go away." On an impulse, thinking of the small gifts I was bringing the

poet from admirers in the West, I did knock. The door opened.

Pasternak stood there, wearing an astrakhan hat. When I introduced

myself he welcomed me cordially as my father's daughter- they had met

in Berlin in the twenties. Pasternak's intonations were those of his poems.

In an instant the warm, slightly nasal singsong voice assured me that

my parents' country still existed and that it had a future as real as

that sunny day. Today, no matter how harsh life in Russia is, that flash

of feeling is proven true. Russia has survived, and the natural world

around us which Pasternak celebrated is as wondrous as ever.

Thơ của Pasternak thì như “strobe light” – nhoáng 1 phát, nó vén lên

một góc vũ trụ, mắt thường, mắt trần không nhìn thấy. Tôi tương tư những bài

thơ, ngay từ khi còn là 1 đứa trẻ. Chúng mới thần kỳ, ma mị làm sao, những

mảnh vụn của thế giới tự nhiên, bình thường được tóm bắt vào những từ mà

tôi luôn không hiểu.

Pasternak là nhà thơ “favorite” của ông già tôi. Vào những buổi

chiều tối, ông thường lớn giọng đọc cho tôi nghe những bài thơ của Pasternak,

hay của Marina Tsvetayeva, một nguời bạn trong gia đình, thường tới nhà

tôi những năm trước chiến tranh.

Mãi, mãi, sau đó, George Plimpton and Harold Humes mang một Pạt

sống vào trong cuộc đời của tôi. Một năm, hay cỡ đó, sau cái không khí

sang sảng kêu như chuông, của Dr. Zhivago, khi bụi đã bốc

lên xóa mờ xì căng đan - bị bắt buộc không được nhận giải - họ, hai đấng

trên, trao cho tôi mission, tới Moscow, gặp nhà thơ, làm 1 cú phỏng vấn

cho tờ The Paris Review.

Tôi không bao giờ

quên được ngày nắng đó, ở Peredelkino, vào mùa đông 1959-1960, chỉ vài tháng

trước khi Pasternak mất. Tuyết long lanh, những cây linh sam, một nửa mẩu

giấy găm trên cánh cửa hành lang bên phiá căn nhà: “Lúc này tôi đang bận

việc. Tôi không tiếp ai. Làm ơn khi khác.” Nghĩ đến những gói quà nhỏ tôi

mang tới cho nhà thơ từ những người mến mộ ông, từ Tây Phương, bất giác tôi

giơ tay gõ cửa. Cửa mở.

Pasternak đứng đó, đội 1 cái mũ astrakhan. Khi tôi tự giới thiệu,

ông niềm nở đón tiếp, như là cô con gái của ba tôi - cả hai đã từng gặp

nhau ở Berlin, vào thập niên 1920. Giọng nói của ông như giọng thơ của

ông. Trong một thoáng, cái giọng nói ấm áp, có tí giọng mũi, nghe như hát,

bảo đảm cho tôi một điều, là xứ sở của cha mẹ tôi vẫn hiện hữu, và nó đã

có 1 tương lai, thực, như ngày nắng này. Bây giờ, dù cuộc sống ở Nga cực

nhọc cỡ nào, cái thoáng chốc của cảm giác đó, được chứng thực. Nga xô đã

sống sót, và cái thế giới thiên nhiên chung quanh chúng tôi mà Pasternak ăn

mừng, thì thần kỳ, tuyệt cú mèo, như vẫn là, như mãi mãi vưỡn là.

Đọc bài viết 1 phát, thì cái đầu óc bịnh hoạn của Gấu Cà Chớn lại hiện ra cái cảnh 1 nhà thơ hải ngoại, đi cùng, cũng 1 nhà thơ hải ngoại - bạn của GCC, nhưng còn là cựu sĩ quan VNCH, bỏ chạy kịp trước 30 Tháng Tư 1975, không có lấy 1 ngày cải tạo làm thưốc chữa bịnh lưu vong - bèn bò về, xin yết kiến nhà thơ HC, và 1 ông châm cái đóm, hầu thuốc lào nhà thơ số 1 Đất Bắc!

Và nhà thơ HC bèn an ủi hai nhà thơ hải ngoại, quê hương của chúng ta vưỡn còn!Thơ Mít vưỡn còn!

Lá diêu bông cũng vưỡn còn, nhưng thuộc hàng chiến lược, hàng xuất khẩu quan trọng, qua xứ người nhiều rồi!

Vào mùa hè năm 1924, Osip Mandelstam đưa cô vợ trẻ đến gặp tôi (ở Fontanka). Nadyusha là 1 người phụ nữ mà tụi Tẩy gọi là laide mais charmante (homely but charming]. Tình bạn của tôi với Nayusha bắt đầu và tiếp tục cho đến bây giờ.

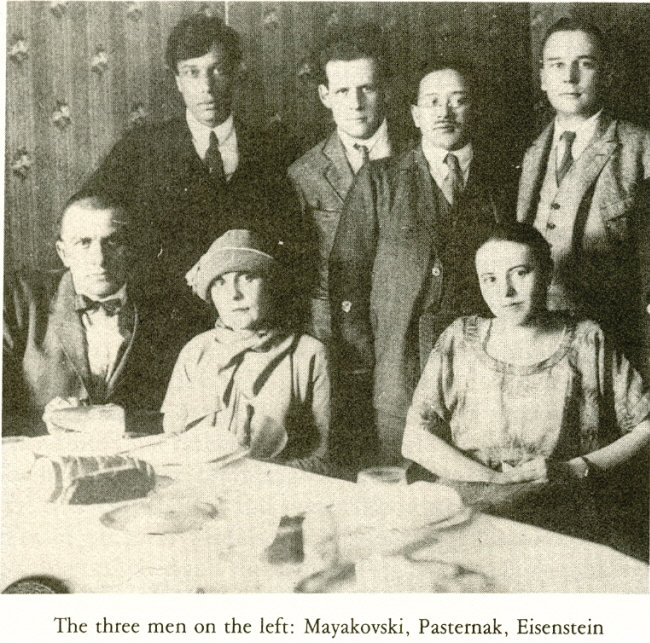

Looking on a Russian Photograph, 1928/1995

It's the classic picture of doom.

Three great poets stand together in 1928, the Revolution just a decade old,

their hearts and brains soon to be dashed out on the rocks of Russian fascism,

the flower of their achievements destined to be crushed by the new czar,

Stalin.

Eisenstein, Mayakovski, Pasternak - each will die in his own tortured

way. Mayakovski, rebuffed in love, imprisoned in Moscow, will kill himself

in 1930, at the age of thirty-six. Eisenstein's broken heart will give

out in 1948, cherished projects betrayed, the fifty-year-old filmmaker

persecuted abroad and closely watched at home. Pasternak, long denied by

his government, will finally survive Stalin - yet, when his magnum opus,

Doctor Zhivago, earns him the Nobel Prize in 1958, he will not be permitted

to accept, his book burned, his name excoriated in his homeland.

But there they stand in 1928, brave young hearts, frozen in triumph,

the last symbols of a civilization about to go mad. Yet I find. myself

thinking - how lucky they are, these three, able to experience lives of

great crisis and choice. Were they not gifted with an energy that brought

them each full-bore into what Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes called the

"passion and peril of their times"?

We shall all lose, it is inevitable. The issue is how we lose,

on what terms. These three men played out their lives across the dark

landscape of a cursed country, each sought as a solace from a mad czar,

who with quasi-Asiatic mind tortured them with the impossibility of reason.

I do not seek such death. I choose the milder climes of the USA

circa the late twentieth century - although these times, less sinister

certainly than Stalinist ones, may be equally dangerous-for what is in

danger, in the largest sense, is the soul. And the soul that dies in its

lifetime is the sterile, timid, cynical soul that is never tested by its

time. Though tests too can be boredom. Luxury, television and the accelerating

sameness of information can be far more ruthless than war or disease.

So I say-in death, rest. There is much time later to sleep.

Until then party - party hard, suffer hard. Live lives suffused

with cycles of joy and sorrow. Participate above all in the travails of

your time, as artists your shoulders equal to all working and struggling

people, neither higher nor lower but equal to its spirit in its own time.

Vladimir Mayakovski, Sergei Eisenstein, Boris Pasternak - I salute

you.

- Oliver Stone

The Paris Review Winter 1995: Russian Portraits

Quái đản thật. Ở cái xứ VC Niên

Xô này, ngay cả những tay theo Đảng, phò Đảng thì cũng bảnh, cực bảnh,

như bộ ba trên đây.

Vladimir Mayakovski, Sergei Eisenstein, Boris Pasternak - Gấu Cà

Chớn chào các bạn!

Ở cái xứ Bắc Kít, toàn Kít!

Một bức hình cổ điển về đọa đầy, trầm luân, bất hạnh…Ba nhà thơ lớn chụp chung với nhau vào năm 1928, Cách Mạng thì mới được 10 tuổi, tim và óc của họ sẽ nát bấy ra trên những hòn đá của phát xít Nga, bông hoa thành tựu sẽ bị nghiền nát dưới gót giầy của sa hoàng mới của Nga – Stalin. Eisenstein, Mayakovski, Pasternak - mỗi người một cái chết, mỗi người một cuộc tra tấn riêng. Mayakovski, bị cự tuyệt trong tình yêu, bị cầm tù tại Moscow, tự sát vào năm 1930, ở tuổi đời 36. Trái tim bể của Eisenstein ngưng đập vào năm 1948, những đồ án nâng niu bị phản bội, nhà làm phim 53 tuổi bị truy đuổi bách hại khi ở hải ngoại, bị canh trừng chặt chẽ khi ở nhà.

Pasternak, đã từ lâu bị nhà cầm quyền của ông chối từ, sau cùng sống sót chế độ Stalin – tuy nhiên khi tuyệt tác của ông Bác Sĩ Zhivago được trao Nobel, ông không được phép đi nhận giải, sách bị đốt, tên bị trà đạp bôi nhọ ở quê nhà.

Nhưng, như bức hình cho thấy, ba nhà thơ đứng hiên ngang, vào năm 1928, ba trái tim trẻ, can đảm, đông lạnh trong chiến thắng, những biểu tượng sau cùng của 1 nền văn minh trước khi khùng điên, ba trợn. Tuy nhiên, riêng tôi, thì lại nhận ra 1 điều, họ mới hạnh phúc, may mắn biết bao, khi cả ba có thể kinh nghiệm những cuộc khủng hoảng lớn, và chọn lựa lớn.*

“I salute U”, là câu nổi tiếng, vang lên ở đấu trường giác đấu, ai hay coi phim La Mã thì chắc rất rành. Oliver Stone, là tay làm phim người Mẽo, cũng rất mê xứ Mít.

Winter 1995: Một trong những số báo đầu

tiên của GCC, April, 98. Trong có bài phỏng vấn Steiner. Bèn chơi liền!

Ba bài thơ của Simic, là tìm đọc sau đó.

Và "Chân Dung Nga", trong có bức hình Akhmatova.

Charles Simic

Against Winter

The truth is dark under your

eyelids.

What are you going to do about it?

The birds are silent; there's no one to ask.

All day long you'll squint at the gray sky.

When the wind blows you'll shiver like straw.

A meek little lamb you grew your

wool

Till they came after you with huge shears

Flies hovered over your open mouth,

Then they, too, flew off like the leaves,

The bare branches reached after them in vain.

Winter coming. Like the last

heroic soldier

Of a defeated army, you'll stay at your post,

Head bared to the first snowflake.

Till a neighbor comes to yell at you,

You're crazier than the weather, Charlie.

The Paris Review, Issue 137,1995

Chống Đông

Sự thực thì mầu xám dưới mi mắt

anh

Anh sẽ làm gì với nó?

Chim chóc nín thinh; không có ai để hỏi.

Suốt ngày dài anh lé xệch ngó bầu trời xám xịt

Và khi gió thổi, anh run như cọng rơm.

Con cừu nhỏ, anh vỗ béo bộ lông

của anh

Cho tới bữa họ tới với những cây kéo to tổ bố

Ruồi vần vũ trên cái miệng há hốc của anh

Rồi chúng cũng bay đi như những chiếc lá

Cành cây trần trụi với theo nhưng vô ích.

Mùa Đông tới. Như tên lính anh

dũng cuối cùng

Của một đạo quân bại trận, anh sẽ bám vị trí của anh

Đầu trần hướng về bông tuyết đầu tiên

Cho tới khi người hàng xóm tới la lớn:

Mi còn khùng hơn cả thời tiết, Charlie. (1)

The portraits that follow are from a large number of photographs recently recovered from sealed archives in Moscow, some-rumor has it-from a cache in the bottom of an elevator shaft. Five of those that follow, Akhmatova, Chekhov (with dog), Nabokov, Pasternak (with book), and Tolstoy (on horseback) are from a volume entitled The Russian Century, published early last year by Random House. Seven photographs from that research, which were not incorporated in The Russian Century, are published here for the first time: Bulgakov, Bunin, Eisenstein (in a group with Pasternak and Mayakovski), Gorki, Mayakovski, Nabokov (with mother and sister), Tolstoy (with Chekhov), and Yesenin. The photographs of Andreyev, Babel, and Kharms were supplied by the writers who did the texts on them. The photograph of Dostoyevsky is from the Bettmann archives. Writers who were thought to have an especial affinity with particular Russian authors were asked to provide the accompanying texts. We are immensely in their debt for their cooperation.

The Paris Review Winter 1995

Chân Dung Nga

Những bức hình sau đây là từ

một lố mới kiếm thấy, từ những hồ sơ có đóng mộc ở Moscow, một vài bức

có giai thoại riêng, thí dụ, đã được giấu kỹ trong ống thông hơi ở tận

đáy thang máy! Năm trong số, Akhmatova, Chekhov [với con chó], Nabokov, Pasternak

(với sách), và Tolstoy (cưỡi ngựa), từ một cuốn có tên là Thế Kỷ Nga, xb

cuối năm ngoái [1997], bởi Random House. Bẩy trong cuộc tìm kiếm đó không

được đưa vô cuốn Thế Kỷ Nga, và được in ở đây, lần thứ nhất: Bulgakov, Bunin,

Eisenstein (trong một nhóm với Pasternak and Mayakovski), Gorki, Mayakovski,

Nabokov (với mẹ và chị/em) Tolstoy (với Chekhov), and Yesenin. Hình Andreyev,

Babel, và Kharms, do những nhà văn kiếm ra cung cấp, kèm bài viết của họ

về chúng. Hình Dostoyevsky, từ hồ sơ Bettmann. Những nhà văn nghe nói có

giai thoại, hay mối thân quen kỳ tuyệt về những tác giả Nga, thì bèn được

chúng tôi yêu cầu, viết đi, viết đi, và chúng tôi thực sự cám ơn họ về

mối thịnh tình, và món nợ lớn này.

*

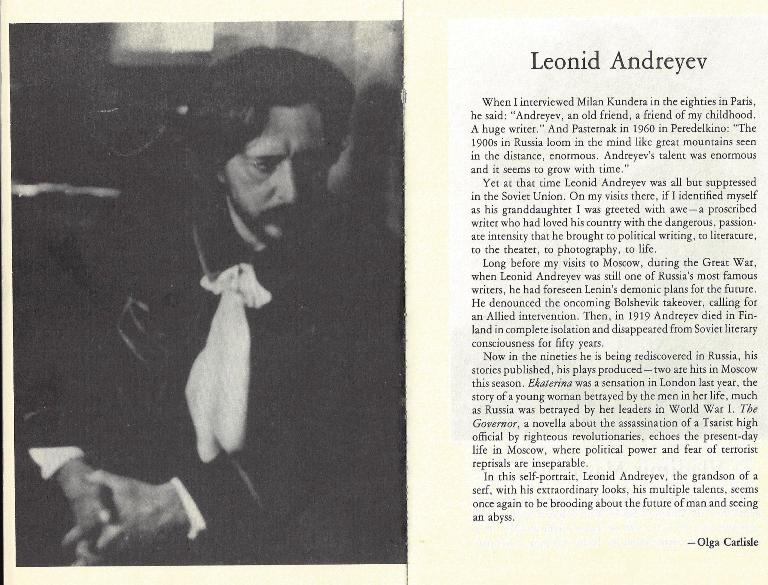

Khi tôi phỏng vấn Milan Kundera

vào thập niên 80 ở Paris, ông nói, “Andreyev, một bạn cũ, thời niên thiếu.

Nhà văn bự".