L'ethnologue Claude Lévi-Strauss est mort

L'ethnologue Claude Lévi-Strauss est mort

LEMONDE.FR | 03.11.09 | 17h20 •

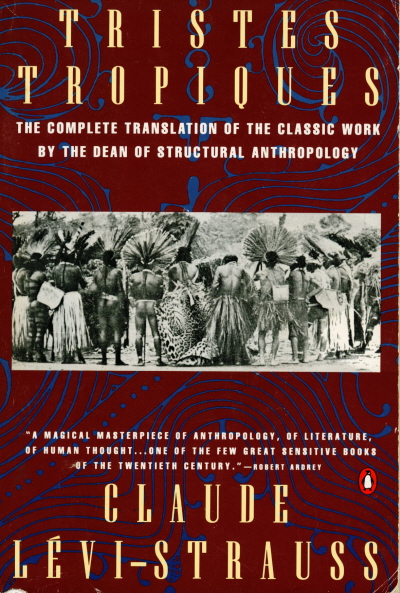

L'ethnologue et anthropologue Claude Lévi-Strauss est mort dans la nuit du samedi 31 octobre au dimanche 1er novembre à l'âge de 100 ans, selon le service de presse de l'Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) contacté par Le Monde.fr. Plon, la maison d'édition de l'auteur de Tristes Tropiques, a également confirmé l'information diffusée par Le Parisien.fr en fin d'après-midi. Claude Lévi-Strauss, qui a renouvelé l'étude des phénomènes sociaux et culturels, notamment celle des mythes, aurait eu 101 ans le 28 novembre.

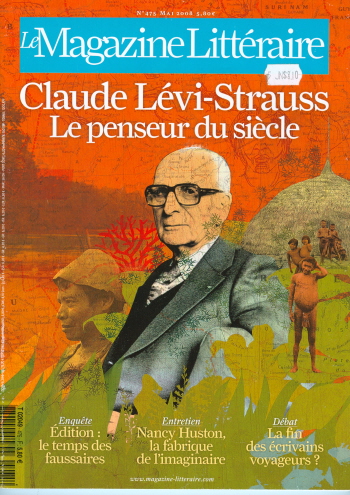

A l'occasion de la publication de son oeuvre dans la "Bibliothèque de la Pléïade" en mai 2008, Roger-Pol Droit avait publié dans Le Monde un portrait de l'ethnologue que nous vous proposons de retrouver ici:

A qui doit-on cette pensée immense ? Un philosophe ? Un ethnologue, un anthropologue, un savant, un logicien, un détective ? Ou encore un bricoleur, un écrivain, un poète, un moraliste, un esthète, voire un sage ? Seule réponse possible : toutes ces figures ensemble se nomment Claude Lévi-Strauss. Leurs places varient évidemment selon les livres et les périodes. Mais il existe toujours une correspondance, constante et unique, entre ces registres, usuellement distincts et le plus souvent incompatibles. Car cette oeuvre ne se contente pas de déjouer souverainement les classements habituels. Elle invente et organise son espace propre en les traversant et en les combinant sans cesse.

Depuis une naissance à Bruxelles le 28 novembre 1908 jusqu'à la publication, ces derniers jours, de deux mille pages dans la "Bibliothèque de la Pléiade", le parcours de Lévi-Strauss suit un curieux périple. Il commence dans l'atelier de son père, qui était peintre, se poursuit par une série de mutations dont l'inventaire comprend, entre autres, l'agrégation de philosophie, le choix de l'anthropologie, le parcours du Mato Grosso, l'exil à New York pendant la guerre, l'adoption de la méthode structurale, la notoriété mondiale, le Collège de France, l'Académie française et l'apparent retour à la peinture dans son dernier livre publié (Regarder écouter lire, Plon, 1993). Résultat : des voies nouvelles pour scruter l'humain.

Trait essentiel : l'exigence sans pareille de remonter continûment d'une émotion aux formes qui l'engendrent - pour la comprendre sans l'étouffer. Lévi-Strauss ne cesse de débusquer la géométrie sous la peinture, le solfège sous la mélodie, la géologie sous le paysage. Dans le foisonnement jugé imprévisible des mythes, il discerne une grammaire aux règles strictes. Dans l'apparent arbitraire des coutumes matrimoniales, il découvre une logique implacable. Dans le prétendu fouillis de la pensée des "sauvages", il met au jour une complexité, une élaboration, un génie inventif qui ne le cède en rien à ceux des soi-disant "civilisés".

Cette symbiose du formel et du charnel, il n'a cessé de la parfaire. Le choix que Claude Lévi-Strauss a opéré parmi ses livres pour "la Pléiade" le confirme. Mais à sa manière : indirectement, sous la forme, au premier regard, d'un paradoxe. Il est curieux, en effet, que les textes qui eurent le plus fort impact théorique n'aient pas été retenus. Ainsi ne trouve-t-on dans ce choix d'oeuvres ni Les Structures élémentaires de la parenté (1949), ni les deux recueils d'Anthropologie structurale (1958 et 1973), ni les quatre volumes des Mythologiques ! Le luxe suprême, pour l'auteur de chefs-d'oeuvre multiples, serait-il de les trier sur le volet ? Réunir notamment Tristes Tropiques, la Pensée sauvage, La Potière jalouse et bon nombre d'inédits, c'est proposer une lecture indispensable.

EFFETS DE SENS

Malgré tout, on peut s'interroger sur les effets de sens induits par ce regroupement, les présences et les absences. Finalement, en écartant les travaux techniques qui s'adressent aux experts, cette "Pléiade" propose un Lévi-Strauss plus aisément accessible au public. L'ensemble déplace le centre de gravité vers la dernière partie de l'oeuvre, avec La Voix des masques (1975), Histoire de Lynx (1991), Regarder écouter lire. L'anthropologue se montre ici, globalement, plus écrivain que scientifique - à condition de ne surtout pas entendre par là un quelconque retrait de la réflexion au profit du récit et du plaisir du style. La force de ce maître est au contraire de toujours tenir ensemble et l'expérience sensible et son arrière-plan théorique.

On laissera donc de côté l'idée que les structures seraient des formes ternes, résidant dans des sous-sols gris. Elles habitent avec éclat les séquences chamarrées du monde, expliquent le système des masques indiens aux couleurs vives aussi bien que celui des mélodies de Rameau. Cette bigarrure bien tempérée est la marque de Lévi-Strauss. A New York, il apprit à fusionner l'insolite et le formalisme, en fréquentant André Breton aussi bien que Roman Jakobson. De Rousseau, il a retenu la fraternité de la nature perdue, de Montaigne le scepticisme enjoué, et le sens quasiment bouddhique de la discontinuité des instants. Mais il ne doit qu'à lui-même la fusion permanente de ces registres en un style.

Comment dire, par exemple, que le village bororo, de feuillages noués et tressés, entretient avec les corps de tout autres relations que nos villes ? "La nudité des habitants semble protégée par le velours herbu des parois et la frange des palmes : ils se glissent hors de leurs demeures comme ils dévêtiraient de géants peignoirs d'autruche." Une autre page de Tristes Tropiques précise : "C'est une étrange chose que l'écriture." Plus encore quand elle unit d'oeuvre en oeuvre mathématiques et poésie. Heureux ceux qui ont encore à découvrir.

Roger-Pol

Droit

L'ethnologue Claude Lévi-Strauss est mort

Nhà nhân chủng học Claude Lévi-Strauss đã mất

Claude-Lévi Strauss phân chia lịch sử ra

những thời kỳ nóng, thời kỳ lạnh. Vào những thời kỳ lạnh, có khi kéo

dài nhiều

thế kỷ, nó chẳng đẻ ra được một ý thức, một tư tưởng, một ý thức hệ,

một triết

lý lớn lao nào.

“Thời của chúng tôi” nóng. Nóng lắm. Bên trời Tây, đó là lúc cơ cấu

luận đang ở

đỉnh cao, với rất nhiều triết gia, nhiều tác phẩm: Viết của

Lacan, Chữ

và Vật, của Michel Foucault, Phê Bình và Chân Lý của Roland

Barthes, Lý thuyết Văn chương, của Todorov… cùng xuất hiện

vào năm 1966. Năm sau 1967,

là những cuốn tiếp theo của bộ Huyền Thoại Học của Claude-Lévi

Strauss: Từ

mật ong tới tàn thuốc, Nguồn gốc của những trò lẩm cẩm muỗng

nĩa, dao

kéo.. ở bàn ăn [L’origine des manières de table],1968, Con

người

trần trụi, L’Homme nu, 1971.

Nhưng Ấu châu có ở trong đó ? Chính họ tự hỏi. Và tuổi trẻ của Tây trả

lời,

bằng biến cố Tháng Năm 1968: Hãy mạnh dạn đòi hỏi những điều không thể

được,

không thể đòi hỏi. Càng làm tình bao nhiêu, càng cách mạng bấy nhiêu.

Octavio Paz, Nobel văn chương, có lần đưa ra một nhận xét thật độc đáo,

về biến

cố Tháng Năm 1968: Văn minh Tây Phương độc đáo ở chỗ, đã biến dục tình

thành

một vũ khí chính trị.

Nhưng 1968 cũng là năm pháo đài bay B.52 vào trận tại cuộc chiến Việt Nam.

Cùng với 276

ngàn binh sĩ Hoa Kỳ.

1965: Cuộc Đổ Bộ Normandie Á Châu, tại bãi biển Đà Nẵng.

1968: Cú Mậu Thân. Mồ Chôn Tập Thể Huế.

The century of Claude

Lévi-Strauss

Thế kỷ Claude Lévi-Strauss

Lévi-Strauss nhìn thấy, ở trong phát minh ra giai điệu, như là một "chìa khóa để tới với sự bí ẩn tối thượng" của con người.

G. Steiner: A Death of Kings

George Steiner, trong bài viết

"Orpheus với những huyền thoại của

mình: Claude Lévi-Strauss", vinh danh một trong những trụ cột của

trường

phái cơ cấu, đã cho rằng, một trang viết của Lévi-Strauss là không thể

bắt

chước được; hai câu mở đầu thiên bút ký "Nhiệt Đới Buồn" đã đi vào

huyền thoại học của ngôn ngữ Pháp.

Hai câu mở đầu đó như sau: "Je hais les voyages et les explorateurs. Et

voici

que je m’apprête à raconter mes expéditions." (Tôi ghét du lịch, luôn

cả mấy

tay thám hiểm. Vậy mà sắp sửa bầy đặt kể ra ở đây những chuyến đi của

mình).

Đỗ Long vân: Vô Kỵ giữa chúng ta

*

A qui

doit-on cette pensée immense ? Un philosophe ? Un ethnologue, un

anthropologue, un savant, un logicien, un détective ? Ou encore un bricoleur, un écrivain,

un poète, un moraliste, un esthète, voire un sage ? Seule réponse

possible : toutes ces figures ensemble se nomment Claude Lévi-Strauss.

Leurs places varient évidemment selon les livres et les périodes. Mais

il existe toujours une correspondance, constante et unique, entre ces

registres, usuellement distincts et le plus souvent incompatibles. Car

cette oeuvre ne se contente pas de déjouer souverainement les

classements habituels. Elle invente et organise son espace propre en

les traversant et en les combinant sans cesse.

Le Monde

Ở trên,

trong phần ghi chú,

người giới thiệu đã cho rằng, Đỗ Long Vân đã sử dụng cơ cấu luận như

một phương

pháp "tiện tay, đương thời" để đọc Kim Dung.

Gérard Genette, trong bài

"Cơ cấu luận và phê bình văn học", in trong Hình Tượng I (Figures I,

nhà xb Seuil, tủ sách Essais, 1966), đã nhắc tới một chương trong cuốn

Tư Tưởng

Hoang Sơ (La Pensée Sauvage) theo đó, Lévi-Strauss đã coi tư tưởng

huyền thoại

như là "một kiểu loay hoay về tinh thần" (une sorte de bricolage

intellectuel). Chúng ta có thể mượn quan niệm trên đây của

Lévi-Strauss, để

giải thích tại sao Đỗ Long Vân lại dựa vào cơ cấu luận, khi viết "Vô Kỵ

giữa chúng ta". Từ đó, chúng ta có thể đi đến kết luận: Vô Kỵ là ai?

(Qui

est Ky?, mượn lại câu hỏi của de Gaulle, khi hoà đàm về Việt Nam đang diễn ra tại Paris; Ky ở đây

là Nguyễn Cao Kỳ). Biết đâu,

nhân đó, chúng ta có thể xác định vai trò của một người viết, như Đỗ

Long Vân,

ở giữa chúng ta.

Thế nào là một tay loay hoay,

hí hoáy (le bricoleur)?

Khác với viên kỹ sư, đồ nào

vào việc đó, nồi nào vung đó, nguyên tắc của "hí hoáy gia" là: xoay

sở từ những phương tiện, vật dụng sẵn có. Những phương tiện, vật dụng,

được sử

dụng theo kiểu "cốt sao cho được việc" như thế, ở trong một hệ thống

lý luận như thế, chúng không còn "y chang" như thuở ban đầu của chúng

nữa.

Cơ cấu luận đã có những thành

tựu lớn lao qua một số tác giả như Lévi-Strauss, Roland Barthes, Gérard

Genette… và nhất là Michel Foucault, cho dù ông đây đẩy từ chối nhãn

hiệu cơ

cấu (làm sao nhét vào đầu óc của những kẻ thiển cận…tôi không hề sử

dụng bất cứ

thứ gì của cơ cấu luận). Trong số những tư tưởng cận đại và hiện đại

như hiện

sinh, cơ cấu, giải cơ cấu, hậu hiện đại… đóng góp của cơ cấu luận là

đáng kể

nhất, theo chủ quan của người viết.

Vô Kỵ giữa chúng ta

Thoạt kỳ thuỷ, con người trần trụi, ăn sống như loài vật, hít mật ong và hỗn như... Gấu. Khi phát minh ra lửa, bèn ăn nướng, ăn thui, dùng lửa để đuổi nước ra khỏi sống. Cộng thêm nước thì biến thành thiu, thối, ủng, nhão, bốc mùi Hà Lội Lụt.

Sống - Chín - Thúi. Đến Thúi là chấm dứt một chu kỳ văn minh, cũng như từ mật ong đến tàn thuốc.

Gấu cũng đã từng sử dụng hình ảnh cái "tam giác trân quí" này để viết về Hà Nội.

*

Bắt chước Vũ Hoàng Chương, C. Lévi-Strauss, tôi cũng tưởng tượng ra một thế chân vạc của Hà-nội. Ở đây, không có nguyên bản, cứ coi như vậy. Chỉ có dịch bản. Một Hà-nội, của những người di cư, 1954. Một, của những người ra đi từ miền Bắc. Và một của những người tù cải tạo, chưa bao giờ biết tới Hà-nội, như của Nguyễn Chí Kham, trong lần ghé ngang, trên chuyến tầu trở về với gia đình.

"Treo đầu dê, bán thịt chó". Quả thế thật. Khi viết Những ngày ở Sài-gòn, là lúc tôi quá nhớ Hà-nội. Mới lớn, vừa mới kịp yêu mến cái cột đèn, cái Hồ Gươm, cái Tháp Rùa, đùng một cái, phải bỏ hết. Vào Nam, cố biến nó thành hiện thực, qua hình ảnh một cô bé Hà-nội. Mối tình tan vỡ, chỉ vì người nghe kể, là một cô bé miền Nam: "Mai, để anh kể cho em nghe, về một thành phố thỉnh thoảng buổi sáng có sương mù...".

Kể từ khi cuốn sách được xb vào năm 1955, nó trở thành nổi tiếng trên thế giới dưới cái tít Tây, thành thử - và cũng theo lời yêu cầu của M. Lévi-Strauss – chúng tôi giữ nguyên tên của nó. Những “Sad Tropics”, “The Sadness of the Tropics”, “Tragic Tropics”… đều không chuyển được ý nghĩa, và hàm ngụ của “Nhiệt đới buồn thỉu buồn thiu”: “Tristes Tropiques”, vừa đọc lên là đã thấy tếu tếu và thơ thơ, ironical and poetic, bởi sự lập đi lập lại của âm đầu, bởi nhịp điệu căng thẳng (- U U – U), bởi giả dụ về một “Hỡi ơi, Nhiệt đới buồn”, “Alas for the Tropiques”.

Cuốn

này đã được dịch ra tiếng

Việt, “Nhiệt đới buồn”.

Đúng ra, nên dịch là Nhiệt đới buồn

thiu, (1) hay buồn hiu, thì vẫn giữ được

tính tếu tếu, lẫn chất thi ca, nhưng, có thể vì đã có cụm từ nổi tiếng

của PTH,

rồi, cho nên đành bỏ chữ "thiu" đi chăng?

Xin giới thiệu, để tham khảo,

bài viết của DMT:

Dương vật buồn thiu

(1)

Cụm từ Nhiệt Đới Buồn Thiu,

hay Buồn Hiu, đã

được sử dụng để dịch cái tít cuốn của Lévi-Strauss từ trước 1975, tại

Miền Nam.

Khi một số lượng

quá đông người phải sống trên một không gian quá hẹp,

thì xã hội tất yếu “tiết ra” sự nô lệ – ông [Lévi-Strauss] viết.

Và sự 'ăn cướp", Gấu viết thêm.

Other Voyages in the Shadow

of Lévi-Strauss

LARRY ROHTER

Đi dưới bóng của me-xừ Lévi-Strauss

NY Times

Whiling away the

time in the hamlet’s one general store, I remarked to the proprietor

that his

shelves seemed empty.

“Aqui so falta o que ñao tem,” he replied: “Here we lack only what we

don’t

have,”

a phrase that I had first run across in “Tristes Tropiques” just a few

days

earlier.

Ở đây chúng tớ thiếu cái mà chúng tớ đếch có!

*

The raw, the cooked and

Claude Lévi-Strauss

If it weren't for the great

anthropologist, who has died aged 100,

I would never have learned a radical new

way of looking at art history

[Dê vật]: Sống, Chín, Thiu, và Buồn Hiu!

Tin

Claude Lévi-Strauss mất

khi ông tròn 100 tuổi khiến hồi ức của tôi những ngày là sinh viên sống

lại, cùng

với chúng, là thời kỳ trấn ngự diễn đàn trí thức của nhà nhân chủng học

vĩ đại

người Pháp này.

Với đám trí thức trẻ thập niên

1980, những cuốn Tư tưởng hoang dại, Sống và Chín chẳng khác chi Thánh

Kinh. Lévi-Strauss

là vị pháp sư hộ pháp, nếu không muốn nói, vị giáo chủ của cơ cấu luận.

Khởi từ

những tư tuởng của nhà ngôn ngữ học Ferdinand Saussure, ông khẳng định,

mọi huyền

thoại, và từ đó, tất cả tư tưởng tiền khoa học, có thể hiểu được bằng

những thuật

ngữ nằm trong dạng đối nghịch – thí dụ như sống và chín.

Vinh quang, lạ lùng và gây

phiền hà, của Lévi-Strauss, hệ tại ở điều, ông khăng khăng bám vào

“đẳng thời, đồng

bộ”, đếch tin vào “bất đồng bộ, phi đẳng thời”, nghĩa là, ông quan tâm

tới những

cấu trúc suy tưởng đường dài, [đường trường biết sức ngựa, thì cứ phán

ẩu như vậy].

Ông có vẻ như đếch tin vào lịch sử, và thay đổi. Quái lạ là, những tư

tưởng của

ông, lại rất có ích, rất đáng quan tâm, đối với những sử gia.

Pourquoi Lévi-Strauss?

Lévi-Strauss, tại sao?

PAR JEAN DANIEL

Pour la société intellectuelle, il est l'homme qui a trouvé dans Montaigne, Rousseau, Bergson et Mauss les bases du concept d'anthropologie structurale, que certains disciples peuvent aujourd'hui juger moins opérationnel, mais qui a renouvelé en profondeur l'anthropologie française. Lévi-Strauss est un maître tout à la fois dépassé et irremplacé. La réfutation de ses thèses est toujours acccompagnée d'une reconnaissance de dette. Au cœur des urgences les plus stimulantes, sa pensée demeure une référence. Mieux que les autres, probablement, il a concepptualisé l'altérité, la différence, la comparaison, l'accouchement du moi par l'autre.

Không

nâng bi mù quáng, thì

người ta có thể nhận ra là, có một số phận nào đó được dành riêng cho

tư tưởng

gia 95 tuổi này. Ông đã được kính trọng, thần tượng hóa, đến biến thành

‘cột đồng

Mã Viện’ [được 'gợi hứng' từ hình ảnh 'dương vật buồn hiu' trong bài

viết của DMT!], trong tất cả các định chế văn hóa của Tây Mũi Lõ.

Người ta ‘nợ’ gì ông ta?

Có lẽ, đó là tác phẩm văn học

hách xì xằng nhất của ông, “Nhiệt Đới Buồn Thiu”, 1955, xém tí nữa thì

đợp

Goncourt, nếu vào phút chót, người ta không nhớ ra rằng thì là,

Goncourt chỉ ban

cho tiểu thuyết, mà cái thứ này của ông, khiến người đọc bị hớp hồn vì

cách

viết, thực sự, đếch phải là giả tưởng!

Hà, hà!

Cuốn sách mở ra bằng một câu

nổi đình nổi đám chẳng thua gì những câu mở ra những cuốn tiểu thuyết

của Proust,

hay của Camus: "Tớ quá chán du lịch và du lịch gia, vậy mà lại ngồi vào

bàn viết về những chuyến đi của mình”

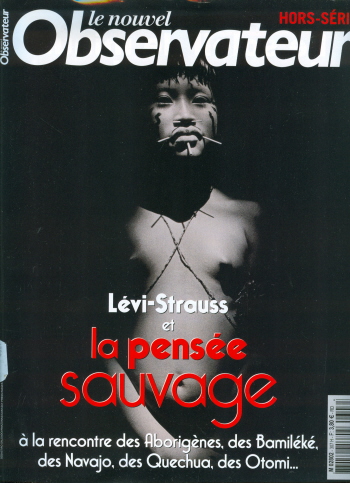

Le Nouvel Observateur,

Người Quan

Sát Mới

Số đặc biệt: Lévi-Strauss và Tư tưởng hoang sơ

*

Muốn

'biết' tại sao dương vật [Mít] buồn hiu, thì đọc bài

của Đỗ Minh Tuấn!

Muốn hiểu tại sao Nhiệt đới buồn hiu, nên đọc tường thuật cú đụng độ

giữa triết gia

Emmanuel Lévinas và nhà nhân chủng học Claude Lévi-Strauss, qua bài

viết của Salomon Malka, trên

tờ Le Magazine Littéraire, số đặc biệt về Lévi-Strauss, mà Gấu trích

dẫn mấy

câu nổi cộm ở trong đó:

"Chủ nghĩa vô thần hiện đại, thì không phải là sự từ chối, phủ nhận

Thượng

Đế, mà là sự dửng dưng tuyệt đối của Nhiệt Đới Buồn Hiu. Theo tôi, đây

là cuốn

sách vô thần nhất từ trước tới giờ được viết ra.”

Câu trên trong, Sự tự do khó khăn, Difficile liberté,

của

Lévinas, một bài viết tàn nhẫn, nhắm vào cuốn đẹp nhất của Lévi-Strauss!

Cùng thế hệ, cùng nguồn gốc,

triết gia và nhà nhân chủng học chẳng hề bao giờ gặp nhau, tuy cùng ở Paris, người xóm

Đông, người

xóm Đoài, thế mới quái!

Họ rất kính trọng lẫn nhau,

thế mới lại càng quái!

Nỗi buồn hiu của Lévi-Strauss,

sau những chuyến tham quan nhiệt đới, là phát giác thê lương, của

‘chàng’: “Thế

giới bắt đầu đếch có con người, và chấm dứt, thì cũng rứa”

[“Le monde a commencé sans l’homme

et s’achèvera sans lui”]

*

Tôi tìm kiếm, trong con người

điều bất biến và cơ bản

“Je recherche dans l’homme ce

qui est constant et fondamental”

Lévi-Strauss trả lời Guy

Sorman, được in trong “Những nhà tư tưởng thực sự của thời đại chúng

ta.”

Lévi-Strauss đã từng được Unesco

‘order’ một cuộc diễn thuyết vào năm 1971, tại Paris, về đề tài “Sắc

tộc và Văn

hóa”. [Race et Culture. Gấu có cuốn này].

Bài diễn thuyết của ông gây xì

căng đan [Gấu nhớ là buổi diễn thuyết bị huỷ bỏ nửa chừng]. Ông cho

rằng chủ

nghĩa bài sắc tộc là một bài diễn văn vô ích [L’antiracisme est un

discours inutile].

Trong lần trả lời phỏng vấn Guy Sorman, ông có giải thích lý do tại sao.

The paradox is irresoluble: the less one culture communicates with another, the less likely they are to be corrupted, one by the other; but, on the other hand, the less likely it is, in such conditions, that the respective emissaries of these cultures will be able to seize the richness and significance of their diversity. The alternative is inescapable: either I am a traveller in ancient times, and faced with a prodigious spectacle which would be almost entirely unintelligible to me and might, indeed, provoke me to mockery or disgust; or I am a traveller of my own day, hastening in search of a vanished reality. In either case I am the loser…for today, as I go groaning among the shadows, I miss, inevitably, the spectacle that is now taking shape.

—from Tristes Tropiques

Sunsan Sontag: A Hero of our Time

Trong có mấy bài thật tuyệt. Thủng thẳng dịch hầu quí vị, bài về Barthes, bài về Lévi-Strauss.

Cũng là một cách tưởng niệm Đỗ Long Vân, cũng quá mê cơ cấu luận

Về chu kỳ hành kinh, vấn đề

kinh nguyệt của phái nữ, đực rựa không

được phép lèm bèm, nhưng đây quả là một vấn nạn, không chỉ dành riêng

cho một

nửa nhân loại.

Trong bộ Thần Thoại của Lévi-Strauss, [hình như trong cuốn Les

manières

de table, Những cách đặt bàn ăn], ông đã mất công sắp xếp, lắp đặt,

cả một

lô những huyền thoại, thành một con đường - của một chiếc thuyền độc

mộc, theo

những dòng sông dẫn tới mặt trăng - chỉ để chứng minh, chúng nói về con

đường

hành kinh của người phụ nữ.

Cô thiếu nữ, trong Những Dòng Sông,

như con cá hồi lần hồi tìm về con kinh, con rạch ngày nào, khi còn một

đứa con

nít, cô vẫn thường bơi lội, và chợt nhớ ra, lần đang tắm, như một đứa

con nít,

thấy dòng nước hồng hồng ấm ấm từ trong mình tỏa ra con kinh, biết rằng

mình

hết còn là con nít, và lần này trở về, không còn là con nít, là thiếu

nữ, là

phụ nữ, mà là một hạt bụi, cái chu kỳ hành kinh như thế, là cả một đời

người.

Có những đấng đàn ông - phần nhiều là có thiên hướng gay - rất

lấy làm

buồn phiền ông Trời, tại làm sao mà 'delete' một trong những thú đau

thương

nhất nhất tuyệt tuyệt như thế, đối với cái PC của họ. Và cái ông nào

đó, khi

đặt tên đứa con tinh thần chỉ có một nửa, bằng cái tên Trăng Huyết, một

cách

nào đó, là đòi 'save' cái thú đau thường kỳ tuyệt này, ít ra là cho

riêng ông

ta.

Nhưng, đây là một lời nguyền, một sự trù ẻo, hay một ân sủng?

*

Có những giây phút, những thời điểm "lịch sử" giầu có vô cùng. Khi

phải nhìn lại lịch sử văn học miền nam - lịch sử của đám chúng tôi! -

văn học

những năm 1960 quả là giầu có vô cùng.

Chỉ với một vài truyện ngắn của nó.

Nếu đi hết biển

*

Trăng Huyết còn nhiều tên gọi.

Với Tuý Hồng, nó có tên là Vết thương dậy thì. [Lẽ dĩ nhiên vết

thương

dậy thì có thể còn một phụ nghĩa, khác]

Giới khoa học gọi bằng cái tên Vết Thương Khôn, The Wise

Wound: tên

tác phẩm của Penelope Shuttle & Peter Redgrove, bàn về kinh nguyệt

và về

mỗi/mọi đàn bà [everywoman]

Trăng huyết? Does the Moon Menstruate?

Liệu vầng trăng kia cũng có... tháng?

Quả có thế. Trong tiếng Anh cổ, chu kỳ kinh nguyệt, the menstrual

cycle, menstrual từ tiếng La tinh mens, mensis,

có nghĩa là month, month/ moon. (1)

(1) Does the Moon Menstruate?

....

But why? What event in human lives corresponds in any way to the moon's

events?

Is there any connection between human fertility and the moon? It seems

a

strange coincidence, if coincidence it is, that lost of the medical

books say

that the average length of a woman's menstrual cycle is twenty-eight

days. This

might be no more than a coincidence, since, as Paula Weideger has

pointed out,

the figure is only an average one composed of the cycle-length of

thousands of

women added together and divided by the number of women. She says that

it is

quite possible in the statistical samples that no woman had a

twenty-eight-day

cycle, since it is quite normal to have fifteen-day cycles or

forty-one-day

cycles. What she says is true – nevertheless is also true that the vast

majority of cycles cluster round this figure of twenty-eight. Around

four weeks

is a very usual length of cycle. The coincidence is that the length of

the

moon's cycle from new moon to new moon also averages out at about four

weeks,

or 29*53 days (mean synodic month). Even the name of the cycle, the

menstrual

cycle, according to the OED, comes from the Latin mens, mensis, leaning

'month', and the same authority also reminds us that nonth' means

'moon'.

Partridge's dictionary goes further. If you look up 'month' there, you

will be

referred to 'measure'. He tells us that the changes of the icon

afforded the

earliest measure of time longer than a day. Under “Menstruation' we are

referred also to 'measure'. The paragraphs tell s that 'menstruation'

does come

from 'month' which comes from noon'. Moreover, he tells us that the

following

words for ideas come from the measurement that the moon makes in the

sky:

measurement, censurable, mensuration, commensurate, dimension,

immensity, metre,

metric, diameter, parameter, preimeter, meal, and many others. A

suspicion

grows that perhaps many of our ideas come from the moon-measure. All

the words

for 'reason’ certainly come from 'ratus', meaning to

count,

calculate, reckon; and all the words for mind, reminder, mental,

comment,

monitor, admonish, mania, maenad, automatic and even money appear to be

associated with this Latin word mens, or Greek menos,

which both

mean 'mind' or 'spirit'; or the Latin for 'moon' or 'monthly'. The

Greek word

for moon is mene.

The Wise Wound

Structuralism Applied:

Kinship and Myth

Những nhà nhân chủng học nhận

thấy trong tất cả những xã hội luôn cấm đoán loạn luân. Một số người đề

nghị

những lý thuyết về tâm lý và sinh học, nhưng chẳng có lý thuyết nào ăn

khớp với

điều hiển nhiên này. Levi-Strauss giải thích, cấm loạn luân phải được

hiểu như

hiện tượng nghịch đảo của hôn nhân. Cấm loạn luân còn đòi hỏi, phải lấy

người

không phải bà con, và, do đó, theo ông, cần giải thích hôn nhân, chứ

không

phải loạn luân.

Ảnh hưởng Marcel Mauss, con rể của Durkheim, khi ông này nghiên

cứu vai trò của sự trao đổi trong xã hội, trong cuốn “The Gift”,

Lévi-Strauss khẳng định, hôn nhân được hiểu một cách hoàn hảo nhất,

không phải

như là một liên hệ giữa một người đàn ông và một người đàn bà, mà như

là một

liên hệ giữa hai người đàn ông, mắc mớ tới chuyện

trao đổi đàn bà. [Lévi-Strauss argued that marriage is

best thought of not as a relationship between a man and a woman but as

a

relationship between two men, bound by the exchange of women].

Ông có được kết

luận như vậy khi nghe một người thổ dân Arapesh trả lời một người hỏi

anh ta,

tại sao mày không lấy chị ruột/em gái ruột của mày: Nếu tao lấy chị

tao/em tao, thì sẽ không có một

bạn săn, là thằng anh em cột chèo của tao!

*

Cấm loạn luân là một trong những

‘bất biến cơ cấu’ [invariants structurels], nó bảo đảm bước tiến từ

con người sinh học qua con

người xã hội [cet interdit assure le passage de l’homme ‘biologique’ à

l’homme

en société. Guy Sorman: Les vrais penseurs de notre temps, những nhà tư

tưởng

thực sự của thời đại chúng ta]

Một cuộc trò chuyện với Lévi-Strauss

không dễ. Trước hết phải kiên nhẫn đợi hàng tháng. Ông không kiếm sự

nổi tiếng,

tác phẩm của ông làm chuyện này rồi. Hơn nữa cái kiểu hỏi/đáp làm phiền

ông, làm

ông ‘lại đâm bực’. Ông thích mặc tình suy nghĩ. “Hãy làm ơn đừng mang

theo máy

ghi âm, như vậy trò chuyện thoải mái và đi sâu vào công việc của tôi

hơn”.

Thật vô ich khi phải nhấn mạnh

đến sự quan trọng của Lévi-Strauss. Tôi chỉ nhắc lại ở đây, ông từ chối

nhận mình

là một nhà trí thức theo nghĩa của Pháp, nghĩa là, có tiếng nói trong

mọi vấn đề.

“Người ta không thể suy nghĩ về tất cả”, ông nói. Tôi chỉ nêu ra ở đây

một nhận

xét có tính cá nhân: trong số những ‘nhà tư tưởng’ mà tôi đã gặp, ông

là người

khiến tôi ngỡ ngàng nhất, bởi sự chính xác, nghiêm ngặt. Mỗi câu hỏi

khiến ông

im lặng thật lâu, rồi tới câu trả lời: ngắn, chắt lọc, rất căng,

incisive, có tính

chung quyết, définitive. Trong những môn học nhân văn cồng kềnh bởi ý

thức hệ và

những bài diễn văn, điều này quả là của hiếm.

Ghi nhận ngoài lề: Lévi-Strauss

là người rất mê sưu tầm [collectionneur]. “Từ hồi 6 tuổi”, ông cho

biết, ‘có thể

chính nó

là lý do mở ra đam mê những gì ở xa, ở cõi ngoài của tôi”. Nhưng chúng

ta đừng

có lầm, kẻ thám hiểm, là ông, không tìm kiếm những đồ vật lạ, hiếm.

Điều ông tìm

kiếm, là bản chất của con người.

Nhu cầu nội tâm nào khiến Lévi-Strauss

trẻ, mới ba chục tuổi, mò tới những đầu sông ngọn nguồn xứ Brésil để

tìm kiếm món

đồ thèm muốn: một bộ lạc ‘man rợ’ thứ thiệt, chân thực [la véritable,

l’authentique

tribu ‘sauvage’]?

“Chắc là do đọc Jean-Jacques Rousseau,” ông nói. “Sự

khám phá

ra Khế ước xã hội và Émile khiến

tôi ao ước tìm lại nhân loại

thuở khởi thuỷ”, cái xã hội như là nó hiện hữu ở vào thời đại đồ đá,

trước khi đi

vào Lịch Sử”… “Tôi muốn tái tạo, reconstituer, cú va chạm khởi thuỷ, le

choc initial,

của cuộc gặp gỡ giữa thổ dân da đỏ và người Âu châu. Nhưng đừng xét

đoán tôi, dựa

trên [sur] Nhiệt Đới Buồn Hiu. Đây

là cuốn tiểu thuyết bên lề tác phẩm

khoa học

của tôi. Tôi bị xô đẩy bởi sự thái quá văn học, thí dụ, khi nhìn thấy

những toán

người da đỏ, đúng như là Rousseau miêu tả trong Khế ước xã hội.”

Chúng ta hãy tách cuốn Nhiệt Đới

Buồn Hiu

ra khỏi những cuốn khác, nhưng hãy nhớ là, cuốn

‘tiểu thuyết’

này đã đóng vai trò ‘tái nhập’, [rehabilitation, rehab, như chúng ta

thường nói,

khi nhắc tới vai trò của những trung tâm cai nghiện], trong thế giới

Tây Phương,

đối với những xã hội ‘hoang sơ’ [primitive], vào thời kỳ mà đâu đâu

cũng xẩy ra

những vận động trục quỉ thực dân [décolonisation]. Lévi-Strauss muốn

‘chứng minh’,

cái trò khai hóa đem ánh sáng Chúa Trời tới cho những dân tộc dã man là

quá nhảm.

Cuốn sách của ông đã để một dấu ấn rất đậm lên lương tâm Tây Phương.

“Nhưng, liệu một xã hội hoang

sơ thì hoàn hảo hơn, so với xã hội Tây phương?”

“Không, nhưng nó hiền hòa,

paisible, và hài hòa, en harmonie, với Thiên nhiên”, ông trả lời.

“Ngoài ước muốn tìm lại một

nền văn minh ‘đã mất’, còn điều gì một nhà nhân chủng học hiện đại muốn

quan sát,

nghiên cứu, ở nơi một bộ lạc hoang sơ?”

“Tôi tìm điều bất biến và cơ

bản ở nơi bản chất của con người”, ông trả lời.

Guy Sorman

Tristes

tropiques:

la quête d'un écrivain

par Pascal Dibie

Tristes tropiques constitue

un genre littéraire à part et nous persuade que

l'ethnologie aurait tout à gagner si les mots qu'elle utilisait étaient

ceux de

la littérature ...

Có thể

nói, tất cả những tác

phẩm của Đỗ Long Vân đặc biệt là Truyện Kiều ABC, đều đã được viết ra,

dưới bùa

chú của cơ cấu luận, và nhất là, dưới những cái bóng râm của "Nỗi buồn

nhiệt đới",

của Lévis-Strauss.

Trong số báo Le Magazine Littéraire,

hors-série, về Lévi-Strauss, có một bài dành riêng cho.... Nỗi Buồn Gác

Trọ, Nỗi Buồn Sến,

hay sử dụng tên của chính một tác phẩm của Lévi-Strauss, Nỗi Nhớ Da Đỏ,

[chắc là

cùng dòng với Ca Khúc Da Vàng, của TCS,

chăng?]:

Vào năm

1994, theo lời yêu cầu

của ông con, Mathieu, Claude Lévi-Strauss chấp nhận cho in những bức

hình chụp ở

Bésil…

Cái tít thoạt đầu của tập hình ảnh là Saudales

do Brasil, là từ âm nhạc.

Trong tiếng Bồ đào nha, Saudales

nghĩa là hoài nhớ, ‘nostalgie’: để biết được

Brésil, Saudales, nhẹ, dịu,

tếu, légèreté, tendresse, ironie, và đây là tinh thần

của xứ đó…. Như Nỗi buồn nhược tiểu, Mít, da vàng, nhiệt đới… như Tristes

Tropiques, cái tít của tập hình ảnh Brésil là từ một nỗi buồn

sâu thẳm, tuy nhiên,

tắm đẫm trong nó, là một nguồn sinh lực hung hãn, une farouche énergie,

không

thể chối cãi được.

Đỗ Long Vân, chỉ viết tiểu luận,

và chỉ tiểu luận mà thôi, cho nên ông chuyển nguồn nghị lực hung hãn

của ông vào

trong đó, biến nó thành một dòng văn chương đầy chất thơ. Nói cách

khác, ông làm

thơ, bằng viết tiểu luận, như Lévi-Srauss, viết nhân chủng học, bằng

văn chương!

Ui

chao, lại nhớ bạn.

Không phải bạn quí.

Không phải bạn [bạc] giả.

Bạn.

*

Whiling away

the

time in the hamlet’s one general store, I remarked to the proprietor

that his

shelves seemed empty.

“Aqui so falta o que ñao tem,” he replied: “Here we lack only what we

don’t

have,”

a phrase that I had first run across in “Tristes Tropiques” just a few

days

earlier.

Ở đây chúng tớ thiếu cái mà chúng tớ đếch có!

Other Voyages in the Shadow

of Lévi-Strauss

LARRY ROHTER

Đi dưới bóng của me-xừ Lévi-Strauss

NY Times

Muốn

'biết' tại sao dương vật [Mít] buồn hiu, thì đọc bài

của Đỗ Minh Tuấn!

Muốn hiểu tại sao Nhiệt đới buồn hiu, nên đọc tường thuật cú đụng độ

giữa triết gia

Emmanuel Lévinas và nhà nhân chủng học Claude Lévi-Strauss, qua bài

viết của Salomon Malka, trên

tờ Le Magazine Littéraire, số đặc biệt về Lévi-Strauss, mà Gấu trích

dẫn mấy

câu nổi cộm ở trong đó:

"Chủ nghĩa vô thần hiện đại, thì không phải là sự từ chối, phủ nhận

Thượng

Đế, mà là sự dửng dưng tuyệt đối của Nhiệt Đới Buồn Hiu. Theo tôi, đây

là cuốn

sách vô thần nhất từ trước tới giờ được viết ra.”

Câu trên trong, Sự tự do khó khăn, Difficile liberté,

của

Lévinas, một bài viết tàn nhẫn, nhắm vào cuốn đẹp nhất của Lévi-Strauss!

Cùng thế hệ, cùng nguồn gốc,

triết gia và nhà nhân chủng học chẳng hề bao giờ gặp nhau, tuy cùng ở Paris, người xóm

Đông, người

xóm Đoài, thế mới quái!

Họ rất kính trọng lẫn nhau,

thế mới lại càng quái!

Nỗi buồn hiu của Lévi-Strauss,

sau những chuyến tham quan nhiệt đới, là phát giác thê lương, của

‘chàng’: “Thế

giới bắt đầu đếch có con người, và chấm dứt, thì cũng rứa”

[“Le monde a commencé sans l’homme

et s’achèvera sans lui”]

*

Tôi tìm kiếm, trong con người

điều bất biến và cơ bản

“Je recherche dans l’homme ce

qui est constant et fondamental”

Lévi-Strauss trả lời Guy

Sorman, được in trong “Những nhà tư tưởng thực sự của thời đại chúng

ta.”

Lévi-Strauss đã từng được Unesco

‘order’ một cuộc diễn thuyết vào năm 1971, tại Paris, về đề tài “Sắc

tộc và Văn

hóa”. [Race et Culture. Gấu có cuốn này].

Bài diễn thuyết của ông gây xì

căng đan [Gấu nhớ là buổi diễn thuyết bị huỷ bỏ nửa chừng]. Ông cho

rằng chủ

nghĩa bài sắc tộc là một bài diễn văn vô ích [L’antiracisme est un

discours inutile].

Trong lần trả lời phỏng vấn Guy Sorman, ông có giải thích lý do tại sao.

*

Tristes tropiques

constitue un genre littéraire à part et nous persuade que l'ethnologie

aurait

tout à gagner si les mots qu'elle utilisait étaient ceux de la

littérature ...

Nhiệt đới buồn tạo

ra một thể loại văn chương riêng, và dụ khị chúng ta, rằng, ngành nhân

chủng học

sẽ được ăn cả, nếu những từ ngữ mà nó sử dụng, là của văn chương....

Ui chao, tuyệt. Áp

dụng câu này vào những tiểu luận của của Đỗ Long Vân, người ta mới nhận

ra một điều

là, mấy thằng viết phê bình không biết viết [bất cứ một thứ viết gì

hết!], tốt nhất là nên kiếm một nghề khác!

Bởi vì tiểu luận,

vốn đã là văn chương, biến nó thành thi ca

mới thật khó bằng trời!

Đây cũng là những dòng Steiner vinh danh Tristes Tropiques.

Tristes

tropiques: la quête d'un écrivain

Nỗi buồn nhiệt đới: cuộc tìm kiếm

của một nhà văn

Nhà văn địa chất

bị kẹt cứng ở giữa hai vách đá, những góc cạnh

cứ thế mỏng đi, những vạt đá cứ thế đổ xuống; thời gian và nơi chốn

đụng

nhau [se heurter] chồng lên nhau, hay xoắn nguợc vào nhau, giống như

những trầm

tích bị cầy xới tung lên do những cơn rung chuyển của môtt cái vỏ quá

già; khi thì là

một tay du lịch hiện đại, khi thì là một tay du lịch cổ xưa, thủ trong

túi một

Montaigne, một Jean de Léry; trong tư tuởng của ông, ngoài ông thầy

Rousseau ra,

những kỷ niệm còn mới tinh....

... chúng ta hãy trở về với những câu hỏi triết học. Kết cục của Regarder Écouter Lire, Nhìn Nghe Đọc, giống của Tristes Tropiques, Nhiệt đới Buồn hiu, giống của L’Homme nu, Con người trần trụi, cuốn chót của bộ Mythologiques, Huyền thoại học: chẳng có gì thì, chẳng có gì đáng, tất cả biến mất. [Rien n’est, rien ne vaut, tout s’évanouit]. Cuốn chót coi bộ lạc quan hơn: “Nhìn từ cái nhìn của những thiên niên kỷ, vue à l’échelle des millénaires, những đam mê của con người trùng lập, lẫn lộn, les passions humaines se confondent (…) Bỏ đi [supprimer] một cách tình cờ, ngẫu nhiên, chừng 10 hoặc 20 thế kỷ, điều này chẳng ảnh hưởng gì đến tri thức của chúng ta đối với thiên nhiên, nói về mặt cảm tính [facon sensible]. Cái mất mát độc nhất không thể nào thay thế, là mất mát những tác phẩm nghệ thuật mà những thế kỷ đó đã thấy chúng xuất hiện. Bởi vì con người chỉ khác biệt, và hơn thế nữa, chỉ hiện hữu, nhờ tác phẩm nghệ thuật.

Như

tượng gỗ đẻ ra từ khúc cây, chỉ nhờ chúng, mà con

người biết rằng, bao nhiêu nước chảy qua cầu, thời gian cứ thế trôi đi,

một điều

gì đó đã thực sự xẩy ra giữa đám người!

Claude Lévi-Strauss trả lời

Cathérine Clément trong bài phỏng vấn:

“De Poussin à Rameau, à Chabanon, à Rimbaud…”

Trong Le Magazine Littéraire,

hors-série, 2003, đặc biệt về Lévi-Strauss.

*

Tuyệt!

Nếu như thế, thì những dòng

sau đây, “ ngàn ngàn đời sau”, giả như còn giống Mít, và giả như có một

tên Mít,

tình cờ đọc nó, thế là những ngày Mậu Thân hiện ra mồn một:

Những ngày Mậu

Thân căng thẳng, Đại Học đóng cửa, cô bạn về quê, nỗi nhớ bám riết vào

da thịt

thay cho cơn bàng hoàng khi cận kề cái chết theo từng cơn hấp hối của

thành phố

cùng với tiếng hỏa tiễn réo ngang đầu. Trong những giờ phút lặng câm

nhìn bóng

mình run rẩy cùng với những thảm bom B52 rải chung quanh thành phố,

trong lúc

cảm thấy còn sống sót, vẫn thường tự hỏi, phải yêu thương cô bạn một

cách bình

thường, giản dị như thế nào cho cân xứng với cuộc sống thảm thương như

vậy...

Kiếp khác

Lại… tự sướng!

A la limite, il serait donc pléonastique de vouloir expliquer pourquoi les Tropiques sont tristes : ils contiennent dans la notion de limite et dans son corrélatif, le cercle, leur propre tristesse. C'est le lieu de se souvenir que triste, dans son origine latine, renvoie à des funérailles et que le long des tropiques, ce qu'a découvert l'ethnologue, c'est le génocide accompli par l'Occident. En un sens nous sommes avec ce livre, dans ce que Freud appelle le travail du deuil, qui entrelace rites obsessionnels et thèmes mythiques autour de l'objet perdu. Cepenndant, « Voyager, c'est ressusciter», a pu écrire Lévi-Strauss. Il faut expliquer ce paradoxe : Tristes Tropiques se trouve curieusement être l'un des premiers livres de l'œuvre; mais il a en même temps valeur de régulation de la pensée tout entière.

Tropiques

Que les femmes cessent d’avoir leurs règles, et tout peut sarrêter, le monde devient un désert. Mais qu’elles avaient sans cesse leurs règles et tout serait inondé, le monde devient un déluge.

Femmes, miel et poison

Catherine Clément: Lévi-Strauss ou la structure et le malheur

A Hero of our Time

Structural Anthropology

The paradox is irresoluble: the less one culture communicates with another, the less likely they are to be corrupted, one by the other; but, on the other hand, the less likely it is, in such conditions, that the respective emissaries of these cultures will be able to seize the richness and significance of their diversity. The alternative is inescapable: either I am a traveller in ancient times, and faced with a prodigious spectacle which would be almost entirely unintelligible to me and might, indeed, provoke me to mockery or disgust; or I am a traveller of my own day, hastening in search of a vanished reality. In either case I am the loser…for today, as I go groaning among the shadows, I miss, inevitably, the spectacle that is now taking shape.

—from Tristes Tropiques

Claude Lévi-Strauss—the man who has created anthropology as a total occupation, involving a spiritual commitment like that of the creative artist or the adventurer or the psychoanalyst—is no man of letters. Most of his writings are scholarly, and he has always been associated with the academic world. Since 1960 he has held a very grand academic post, the newly created chair of social anthropology at the Collège de France, and heads a large and richly endowed research institute. But his academic eminence and ability to dispense patronage are scarcely adequate measures of the formidable position he occupies in French intellectual life today. In France, where there is more awareness of the adventure, the risk involved in intelligence, a man can be both a specialist and the subject of general and intelligent interest and controversy. Hardly a month passes in France without a major article in some serious literary journal, or an important public lecture, extolling or damning the ideas and influence of Lévi-Strauss. Apart from the tireless Sartre and the virtually silent Malraux, he must be the most interesting intellectual figure in France today.

So far, Lévi-Strauss is hardly known in this country. A collection of seventeen previously scattered essays on the methods and concepts of anthropology, brought out in 1958 and entitled Structural Anthropology, has just been published here. Still to appear are another collection of essays, more philosophical in character, entitled La Pensée Sauvage; a book published by UNESCO in 1952 called Race et histoire: and the brilliant works on the kinship systems of primitives. Les Structures élémentaires de la parenté (1949); and on totemism, Le Totemism aujourd’hui (1962). Some of these writings suppose more familiarity with anthropological literature and with the concepts of linguistics, sociology, and psychology than the ordinary cultivated reader has. But it would be a great pity if Lévi-Strauss’s work, when finally translated, were to find no more than a specialist audience in this country. For Lévi-Strauss has assembled, from the vantage point of anthropology, one of the few interesting and possible intellectual positions—in the most general sense of the phrase. And one of his books is a masterpiece. I mean the incomparable Tristes Tropiques, a book which when published in France in 1955 became a best seller, but when translated into English and brought out here in 1961 was shamefully ignored.1 Tristes Tropiques is one of the great books of our century. It is rigorous, subtle, and bold in thought. It is beautifully written. And, like all great books, it bears an absolutely personal stamp; it speaks with a human voice.

Ostensibly Tristes Tropiques is the record, or memoir rather, written over fifteen years after the event, of the author’s experiences in the “field.” Anthropologists are fond of likening field research to the puberty ordeal which confers status upon members of certain primitive societies. Lévi-Strauss’s ordeal was in Brazil, before the second World War. Born in 1908 and of the intellectual generation and circle which included Sartre, de Beauvoir, Merleau-Ponty, and Paul Nizan, he studied philosophy in the late Twenties, and, like them, taught for a while in a provincial lycée. Dissatisfied with philosophy he soon gave up his teaching post, returned to Paris to study law, then began the study of anthropology, and in 1935 went to Sâo Paolo, Brazil, as Professor of Anthropology. From 1935 to 1939, during the long university vacations from November to March and then for longer periods of a year or more. Lévi-Strauss lived among Indian tribes in the interior of Brazil. Tristes Tropiques offers a record of his encounters with these tribes—the nomadic, missionary – murdering Nambikwara, the Tupi-Kawahib whom no white man had ever seen before, the materially splendid Bororo, the ceremonious Caduveo who produce huge amounts of abstract painting and sculpture. But the greatness of Tristes Tropiques lies not simply in this sensitive reportage, but in the way Lévi-Strauss uses his experience—to reflect on the nature of landscape, on the meaning of physical hardship, on the city in the Old World and the New, on the idea of travel, on sunsets, on modernity, on the connection between literacy and power. The key to the book is Chapter Six, “How I Became an Anthropologist,” where Lévi-Strauss finds in the history of his own choice a case study of the unique spiritual hazards to which the anthropologist subjects himself. Tristes Tropiques is an intensely personal book. Like Montaigne’s Essays and Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, it is an intellectual autobiography, an exemplary personal history in which a whole view of the human situation, an entire sensibility is elaborated.

The profoundly intelligent sympathy which informs Tristes Tropiques makes all other memoirs about life among preliterate peoples seem ill-at-ease, defensive, provincial. Yet sympathy is modulated throughout by a hard-won impassivity. In her autobiography Simone de Beauvoir recalls Lévi-Strauss as a young philosophy student-teacher expounding “in his detached voice, and with a deadpan expression…the folly of the passions.” Not for nothing is Tristes Tropiques prefaced by a motto from Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura. Lévi-Strauss’s aim is very much like that of Lucretius, the Graecophile Roman who urged the study of the natural sciences as a mode of ethical psychotherapy. The aim of Lucretius was not independent scientific knowledge, but the reduction of emotional anxiety. Lucretius saw man as hurled between the pleasure of sex and the pain of emotional loss, tormented by superstitions inspired by religion, haunted by the fear of bodily decay and death. He recommended scientific knowledge, which teaches intelligent detachment, equanimity, psychological gracefulness, a way of learning to let go.

Lévi-Strauss sees man with a Lucretian pessimism, and a Lucretian feeling for knowledge as both consolation and necessary disenchantment. But for him the demon is history—not the body or the appetites. The past, with its mysteriously harmonious structures, is broken and crumbling before our eyes. Hence, the tropics are tristes. There were nearly twenty thousand of the naked, indigent, nomadic, handsome Nambikwaras in 1915, when they were first visited by white missionaries; when Lévi-Strauss arrived in 1938 there were no more than two thousand of them; today they are miserable, ugly, syphilitic, and almost extinct. Hopefully, anthropology brings a reduction of historical anxiety. It is interesting that many of Lévi-Strauss’s students are reported to be former Marxists, come as it were to lay their piety at the altar of the past since it cannot be offered to the future. Anthropology is necrology. “Let’s go and study the primitives,” say Lévi-Strauss and his pupils, “before they disappear.”

It is strange to think of these ex-Marxists—philosophical optimists if ever such have existed—submitting to the melancholy spectacle of the crumbling pre-historic past. They have moved not only from optimism to pessimism, but from certainty to systematic doubt. For, according to Lévi-Strauss, research in the field, “where every ethnological career begins, is the mother and nursemaid of doubt, the philosophical attitude par excellence.” In Lévi-Strauss’s program for the practicing anthropologist in Structural Anthropology, the Cartesian method of doubt is installed as a permanent agnosticism. “This ‘anthropological doubt’ consists not merely in knowing that one knows nothing but in resolutely exposing what one knows, even one’s own ignorance, to the insults and denials inflicted on one’s dearest ideas and habits by those ideas and habits which may contradict them to the highest degree.”

To be an anthropologist is thus to adopt a very ingenious stance via-à-vis one’s own doubts, one’s own intellectual uncertainties. Lévi-Strauss makes it clear that for him this is an eminently philosophical stance. At the same time, anthropology reconciles a number of divergent personal claims. It is one of the rare intellectual vocations which do not demand a sacrifice of one’s manhood. Courage, love of adventure, and physical hardiness—as well as brains—are used by it. It also offers a solution to that distressing by-product of intelligence, alienation. Anthropology conquers the estranging function of the intellect by institutionalizing it. For the anthropologist, the world is professionally divided into “home” and “out there,” the domestic and the exotic, the urban academic world and the tropics. The anthropologist is not simply a neutral observer. He is a man in control of, and even consciously exploiting, his own intellectual alienation. A technique de dépaysement, Lévi-Strauss calls his profession in Structural Anthropology. He takes for granted the philistine formulas of modern scientific “value neutrality.” What he does is to offer an exquisite, aristocratic version of this neutrality. The anthropologist in the field becomes the very model of the twentieth-century consciousness: a “critic at home” but a “conformist elsewhere.” Lévi-Strauss acknowledges that this paradoxical spiritual state makes it impossible for the anthropologist to be a citizen. The anthropologist, so far as his own country is concerned, is sterilized politically. He cannot seek power, he can only be a critical dissenting voice. Lévi-Strauss himself, although in the most generic and very French way a man of the Left (he signed the famous Manifesto of the 121 which recommended civil disobedience in France in protest against the Algerian war), is by French standards an apolitical man. Anthropology, in Lévi-Strauss’s conception, is a technique of political disengagement.

Anthropology has always struggled with an intense, fascinated repulsion towards its subject. The horror of the primitive (naively expressed by Frazer and Lévy-Bruhl) is never far from the anthropologist’s consciousness. Lévi-Strauss marks the furthest reach of the conquering of the aversion. The anthropologist in the manner of Lévi-Strauss is a new breed altogether. He is not, like recent generations of American anthropologists, simply a modest data-collecting “observer.” Nor does he have any axe—Christian, rationalist, Freudian, or otherwise—to grind. By means of experience in the field, the anthropologist undergoes a “psychological revolution”. Like Psychoanalysis, anthropology cannot be taught “purely theoretically,” Lévi-Strauss insists in several essays on the profession and teaching of his subject in Structural Anthropology. A spell in the field is the exact equivalent of the training analysis undergone by psychoanalysis. Not written tests, but the judgment of “experienced members of the profession” who have undergone the same psychological ordeal, can determine “if and when” a candidate anthropologist “has, as a result of field work, accomplished that inner revolution that will really make him into a new man.”

However, it must be emphasized that this literary-sounding conception of the anthropologist’s calling—the twice-born spiritual adventurer, pledged to a systematic déracinement—is complemented in most of Lévi-Strauss’s writings by an insistence on the most unliterary techniques of research. His important essay on myth in Structural Anthropology outlines a technique for analyzing the elements of myths so that these can be recorded on IBM cards. European contributions to what in America are called the “social sciences” are in exceedingly low repute in this country, for their insufficient empirical documentation, for their “humanist” weakness for covert culture criticism, for their refusal to embrace the techniques of quantification as an essential tool of research. Lévi-Strauss’s essays in Structural Anthropology certainly escape these strictures. Indeed, far from disdaining the American fondness for precise quantitative measurement of all traditional problems, LéviStrauss finds it not sophisticated or methodologically rigorous enough. At the expense of the French school (Durkheim, Mauss, and their followers), to whom one would expect him to be allied. Lévi-Strauss pays lavish tribute throughout the essays in Structural Anthropology to the work of American anthropologists—particularly Lowie, Boas, and Kroeber. But his real affinity is clearly to the more avant-garde methodologies of economies, neurology, linguistics, and game theory. For Lévi-Strauss, there is no doubt that anthropology must be a science, rather than a humanistic study. The question is only how. “For centuries,” he writes, “the humanities and the social sciences have resigned themselves to contemplate the world of the natural and exact sciences as a kind of paradise where they will never enter.” But recently, a doorway to paradise has been opened by the linguists, like Roman Jakobson and his school. Linguists now know how to reformulate their problems so that they can “have a machine built by an engineer and make a kind of experiment, completely similar to a natural-science experiment,” which will tell them “if the hypothesis is worthwhile or not.” Linguists—as well as economists and game theorists—have shown the anthropologist “a way to get out of the confusion resulting from too much acquaintance and familiarity with concrete data.”

Thus the man who submits himself to the exotic to confirm his own inner alienation as an urban intellectual ends by aiming to vanquish his subject by translating it into a purely formal code. The ambivalence toward the exotic, the primitive, is not overcome after all, but only given a complex restatement. The anthropologist, as a man, is engaged in saving his own soul, by a curious and ambitious act of intellectual catharsis. But he is also committed to recording and understanding his subject by a very high-powered mode of formal analysis—what Lévi-Strauss calls “structural” anthropology—which obliterates all traces of his personal experience and truly effaces the human features of his subject, a given primitive society.

In La Pensée Sauvage, Lévi-Strauss calls his thought “anecdotique et géometrique.” The essays in Structural Anthropology show mostly the geometrical side of his thought: they are applications of a rigorous formalism to traditional themes—kinship systems, totemism, puberty rites, the relation between myth and ritual, and so forth. A great cleansing operation is in process, and the broom that sweeps everything clean is the notion of “structure,” Lévi-Strauss strongly dissociates himself from what he calls the “naturalistic” trend of British anthropology, represented by such leading figures as Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown. According to Malinowski, empirical, observation of a single primitive society will make it possible to understand the “universal motivations” present in all societies. According to Lévi-Strauss, this is nonsense. Anthropology cannot possibly get complete knowledge of the societies it studies; it studies only the formal features which differentiate one society from another, Anthropology can neither be a descriptive nor an inductive science. It has properly no interest in the biological basis, psychological content, or social function of institutions and customs. Thus, while Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown argue, for example, that biological ties are the origin of and the model for every kinship tie, the “structuralists,” like Lévi-Strauss, following Kroeber and Lowie, emphasize the artificiality of kinship rules. They would discuss kinship in terms of notions which admit of mathematical treatment. LéviStrauss and the structuralists, in short, would view society like a chess game. Different societies assign different moves to the players; there is no one right way to play chess. Thus, the anthropologist can view a ritual or a taboo simply as a set of rules, paying little attention to “the nature of the partners (either individuals or groups) whose play is being patterned after these rules.” The analogy between anthropology and linguistics is the leading theme of the essays in Structural Anthropology. All behavior, according to Lévi-Strauss, is a language, a vocabulary and grammar of order; anthropology proves nothing about human nature except the need for order itself. There is no universal truth about the relations between, say, religion and social structure. There are only models showing the variability of one in relation to the other.

To the general reader of Structural Anthropology, perhaps the most striking example of Lévi-Strauss’s theoretical agnosticism is his view of myth. He treats myth as a purely formal mental operation, without any psychological content or any necessary connection with rite. Specific narratives are exposed as logical designs for the description and possibly the softening of the rules of the social game when they give rise to a tension or contradiction. For Lévi-Strauss, the logic of mythic thought is fully as rigorous as that of modern science. The only difference is that this logic is applied to different problems. Contrary to Mircea Eliade, his most distinguished opponent in the theory of primitive religion, Lévi-Strauss sees no difference in quality between the scientific thinking of modern “historical” societies and the mythic thinking of prehistoric communities.

The demonic character which history and the notion of historical consciousness has for Lévi-Strauss is best exposed in his brilliant and savage attack on Sartre, in the last chapter of La Pensée Sauvage. I am not convinced by Lévi-Strauss’s arguments against Sartre. But I should say that he is, since the death of Merleau-Ponty, the only interesting and challenging critic of Sartrean existentialism and phenomenology.

Not only in his ideas, but in his entire sensibility, the antithesis of Lévi-Strauss is Sartre. Sartre, with his philosophical and political dogmatisms, his inexhaustible ingenuity and clotted style, always has the manners (which are often bad manners) of the enthusiast. It is entirely apt that the writer who has aroused Sartre’s greatest enthusiasm is Jean Genet, a baroque and didactic and insolent writer whose ego effaces all objective narrative; whose characters are stages in a masturbatory revel; who is the master of games and artifices, of a rich, over-rich style stuffed with metaphors and conceits. But there is another tradition in French thought and sensibility—the cult of froideur, l’esprit géometrique. This tradition is represented, among the new novelists, by Nathalie Sarraute, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and Michel Butor, so different from Genet in their search for an infinite precision, their narrow dehydrated subject-matter and cool microscopic styles and, among film makers, by Alain Resnais, the director of the great Nuit et Brouillard as well as Hiroshima Mon Amour, L’Année Dernière à Marienbad, and Muriel. The formula for this tradition—in which I would locate Lévi-Strauss, as I would put Sartre with Genet—is the mixture of pathos and coldness.

Like the formalists of the “new novel” and film, Lévi-Strauss’s emphasis on “structure,” his extreme formalism and intellectual agnosticism, are the steely casing for an immense but thoroughly subdued pathos. Sometimes the result is a masterpiece like Tristes Tropiques. The very title is an understatement. The tropics are not merely sad. They are in agony. The horror of the rape, the final and irrevocable destruction of pre-literate peoples taking place throughout the world today—which is the true subject of Lévi-Strauss’s book—is told at a certain distance, the distance of a personal experience of fifteen years ago, and with a sureness of feeling and fact that allows the readers’ emotions more rather than less freedom.

But in the rest of these books, the lucid and brilliantly compassionate documentarist has been overwhelmed by the aesthete, the formalist. The whole point of the new novels and films coming out of France today is to suppress the story, in its traditional psychological or social meaning, in favor of a formal exploration of the structure of an emotion. It is exactly in this spirit that Lévi-Strauss applies the methods of “structural analysis” to traditional materials of empirical anthropology. Customs, rites, myths, and taboo are a language. As in language, where the sounds which make up words are, taken in themselves, meaningless, so the parts of a custom or a rite or a myth (according to Lévi-Strauss) are meaningless in themselves. When analyzing the Oedipus myth, he insists that the parts of the myth (the lost child, the old man at the crossroad, the marriage with the mother, the blinding, etc.) mean nothing. Only when put together in the total context do the parts have a meaning—the meaning that a logical model has. This degree of intellectual agnosticism is surely extraordinary. And one does not have to espouse a Freudian or a sociological interpretation of the elements of myth to contest it.

Any serious critique of Lévi-Strauss, however, must deal with the fact that, ultimately, his extreme formalism is a moral choice, and (more surprisingly) a vision of social perfection. Radically anti-historicist, he refuses to differentiate between “primitive” and “historical” societies. Primitives have a history; but it is unknown to us. And historical consciousness (which they do not have), he argues in the attack on Sartre, is not a privileged mode of consciousness. There are only what he revealingly calls “hot” and “cold” societies. The hot societies are the modern ones, driven by the demons of historical progress. The cold societies are the primitive ones, static, crystalline, harmonious. Utopia, for Lévi-Strauss, would be a great lowering of the historical temperature. In his inaugural lecture at the Collège de France, Lévi-Strauss outlined a post-Marxist vision of freedom in which man would finally be freed from the obligation to progress, and from “the age-old curse which forced it to enslave men in order to make progress possible.” Then:

history would henceforth be quite alone, and society, placed outside and above history, would once again be able to assume that regular and quasi-crystalline structure which, the best-preserved primitive societies teach us, is not contradictory to humanity. It is in this admittedly Utopian view that social anthropology would find its highest justification, since the forms of life and thought which it studies would no longer be of mere historic and comparative interest. They would correspond to a permanent possibility of man, over which social anthropology would have a mission to stand watch, especially in man’s darkest hours.

The anthropologist is thus not only the mourner of the cold world of the primitives, but its custodian as well. Groaning among the shadows, struggling to distinguish the archaic from the pseudoarchaic, he acts out a heroic, diligent, and complex modern pessimism.

Letters

Levi-Strauss January 23, 1964

Comments

Post a Comment