Milosz's ABC's

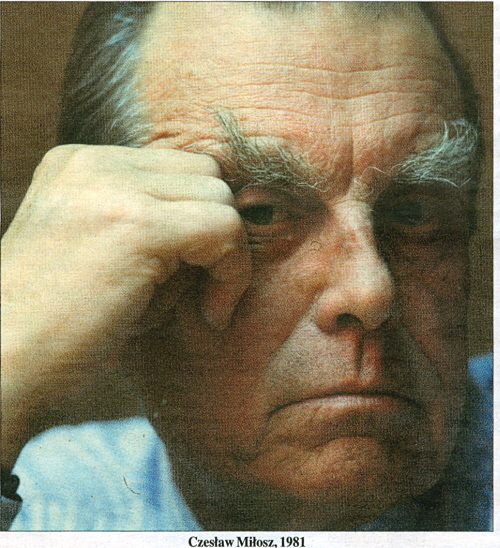

Cầm Tưởng

Ghi Chú Về Lưu Vong Milosz's ABC's

Tưởng Niệm Milosz:

Trí Tuệ và Những Bông Hồng

Giới thiệu

Tởm, Disgust

Dos

Camus

Congrès

Nemo

Koestler

Hatred

Notes about Brodsky

SECRETARIES

I am no more

than a secretary of the invisible thing

That is

dictated to me and a few others.

Secretaries,

mutually unknown, we walk the earth

Without much

comprehension. Beginning a phrase in the middle

Or ending it

with a comma. And how it all looks when completed

Is not up to

us to inquire, we won't read it anyway.

Berkeley,

1975

Tớ thì chỉ là

1 tên thư ký của điều vô hình

Nó đọc cho tớ

và vài người khác

Những tên thư

ký, chẳng quen biết nhau, chúng tớ dạo bộ trên mặt đất

Cũng chẳng ưa

gì nhau mấy. Bắt đầu một câu, ở giữa,

Hay chấm dứt

nó, bằng 1 cái dấu phẩy.

Nó ra sao nhỉ, nhìn toàn thể, khi hoàn tất?

Chắc giống 1

trang, hay 1 bài viết trên TV, hà hà!

Nhưng Gấu Cái

đâu cần biết làm khỉ gì

Cũng chẳng cần

kiểm tra

Bả đâu có đọc!

MID-TWENTIETH-CENTURY

PORTRAIT

Hidden

behind his smile of brotherly regard,

He despises

the newspaper reader, the victim of the dialectic of power.

Says:

"Democracy," with a wink.

Hates the

physiological pleasures of mankind,

Full of

memories of those who also ate, drank, copulated,

But in a

moment had their throats cut.

Recommends

dances and garden parties to defuse public anger.

Shouts:

"Culture!" and" Art!" but means circus games really.

Utterly

spent.

Mumbles in

sleep or anesthesia: "God, oh God!"

Compares

himself to a Roman in whom the Mithras cult has mixed

with the

cult of Jesus.

Still clings

to old superstitions, sometimes believes himself to be

possessed by

demons.

Attacks the

past, but fears that, having destroyed it,

He will have

nothing on which to lay his head.

Likes most

to play cards, or chess, the better to keep his own counsel.

Keeping one

hand on Marx's writings, he reads the Bible in private.

His mocking

eye on processions leaving burned-out churches.

His

backdrop: a horseflesh-colored city in ruins.

In his hand:

a memento of a boy "fascist" killed in the Uprising.

Krakow, 1945

CHÂN DUNG GIỮA THẾ KỶ 20

Giấu đàng

sau nụ cười Anh Hai, Anh Cả

Hắn khinh

thường độc giả nhựt trình, nạn nhân của biện chứng của quyền lực

Này, “Dân chủ

ccc”, với 1 cái nháy mắt.

Thù ghét thú

vui sinh lý của nhân loại

Đầy hồi ức của

những người cũng ăn, ngủ, đụ, ị

Nhưng trong một

khoảnh khắc cổ họng bị cắt.

Đề xuất khiêu

vũ, và hội hè ở trong vườn, để gỡ bỏ sự giận dữ của công chúng.

La: “Văn hóa!” và “Nghệ thuật”, nhưng thực sự, trò xiệc.

Thì cũng qua

thôi, hoàn toàn qua rồi.

Lầm bầm

trong khi ngủ, hay mê: “Ôi Chúa, ôi Phật!”

So sánh chính

mình với 1 tên La Mã, tên này lầm sùng bái Mithras với sùng bái Chúa Ky

Tô.

Vưỡn bám vào

những mê tín cổ xưa, đôi khi tin, bản thân mình bị Quỉ Đỏ đợp mẹ mất

linh

hồn!

Tấn công quá

khứ, nhưng sợ, phá huỷ nó,

Thì sẽ đếch

còn cái chi để mà gối đầu lên

[Chửi Ngụy

ra rả tuy nhiên trong bụng thì sợ và tiếc,

ui chao, sao mà lại huỷ diệt nó, lấy

gì mà… tự hào bi giờ?]

Thích nhất,

chơi bài, cờ, cách tốt để giữ lời khuyên của riêng mình.

Một tay để lên

những trang sách của Marx, đọc Thánh Kinh trong “cõi riêng”.

Mắt chế nhạo

đám rước, bỏ mặc nhà thờ cháy rụi.

Phông đằng

sau hắn: một thành phố điêu tàn màu thịt ngựa.

Trong tay hắn:

Bản “memo” của 1 đứa trẻ “phát xít” bị giết trong cú Nổi Dậy.

Return to Kraków in 1880

So I

returned here from the big capitals,

To a town in

a narrow valley under the cathedral hill

With royal

tombs. To a square under the tower

And the

shrill trumpet sounding noon, breaking

Its note in

half because the Tartar arrow

Has once

again struck the trumpeter.

And pigeons.

And the garish kerchiefs of women selling flowers.

And groups

chattering under the Gothic portico of the church.

My trunk of books

arrived, this time for good.

What I know

of my laborious life: it was lived.

Faces are

paler in memory than on daguerreotypes.

I don't need

to write memos and letters every morning.

Others will

take over, always with the same hope,

The one we

know is senseless and devote our lives to.

My country

will remain what it is, the backyard of empires,

Nursing its

humiliation with provincial daydreams.

I leave for a

morning walk tapping with my cane:

The places

of old people are taken by new old people

And where

the girls once strolled in their rustling skirts,

New ones are

strolling, proud of their beauty.

And children

trundle hoops for more than half a century.

In a

basement a cobbler looks up from his bench,

A hunchback

passes by with his inner lament,

Then a

fashionable lady, a fat image of the deadly sins.

So the Earth

endures, in every petty matter

And in the

lives of men, irreversible.

And it seems

a relief. To win? To lose?

What for, if

the world will forget us anyway.

- CZESLAW MILOSZ

(translated by Milosz and Robert Hass)

Trở lại Krakow năm 1880

Vậy là tôi trở

về đây từ những thủ đô lớn

Về thành phố

trong thung lũng hẹp dưới ngọn đồi nhà thờ

Với những ngôi

mộ vương giả.

Về quảng trường

dưới ngọn tháp

Và tiếng kèn

the thé báo ngọ,

bị đứt đoạn

bởi mũi tên

của rợ Tác ta,

một lần nữa

cắm vào người thổi kèn.

Và những con

bồ câu. Và những tấm khăn mỏ quạ sặc sỡ của những phụ nữ bán hoa..

Và những nhóm

người trò chuyện bên dưới cổng xây theo kiểu Gothic của nhà thờ.

Cái xe chở sách

của tôi đã tới, vào lúc này thật được.

Điều tôi biết

về cuộc đời cần cù của mình: nó được sống.

Những khuôn

mặt thì mờ nhạt đi ở trong hồi ức, hơn là trong “daguerreotypes”

Tôi đầu cần

viết “memo” hay thư từ mọi buổi sáng.

Những người

khác sẽ làm, luôn luôn với cùng 1 hy vọng.

Thứ hy vọng

mà chúng ta biết, vô nghĩa, và dâng hết đời mình cho nó

Xứ sở của tôi

thì sẽ như là nó vẫn là, cái sân sau của những đế quốc

Nuôi nấng sự

tủi nhục của nó với những giấc mộng ngày miệt vuờn, đặc sản.

Tôi làm 1 cú

tản bộ cùng với cây gậy của mình:

Những nơi chốn

mấy người già cả ngày xưa hay ngồi thì bây giờ, là những người già cả

mới

Và nơi những

cô gái đã từng dạo bước, trong những chiếc áo cánh sột soạt

Thì là những

cô gái mới dạo bước, hãnh diện với nhan sắc của họ

Và những đứa

trẻ đánh vòng hơn một nửa thế kỷ

Ở dưới tầng

hầm 1 căn nhà, một người bạn từ thời nối khố ngước mắt nhìn lên từ

chiếc ghế dài

đang ngồi

Một người gù

lưng đi ngang qua với nỗi ngậm ngùi ngậm kín

Rồi thì một

bà ăn mặc đúng thời trang, một hình ảnh mập mạp, đầy mỡ, của những tội

lỗi chết

người.

Ui trái đất

thì cứ thế cứ thế, trong mọi vẻ tầm phào của nó.

Và những cuộc

sống của con người, không hề đảo ngược lại được.

Và có vẻ như

đây là 1 sự khuây khỏa. Được? Mất?

Để làm gì cơ

chứ? Một khi mà thế giới sẽ quên béng chúng ta, gì thì gì, làm sao

không?

Note: GCC dọc

bài thơ này, trong tập thơ của Raymond Carver.

Thú vị là, bài thơ thứ nhì, của

Milosz, Quà Tặng, Gift, được

in trong đó, đã post trên Tin Văn.

Một tình cờ

thú vị:

A day so

happy.

Fog lilted

early, I worked in the garden.

Hummingbirds

were stopping over honeysuckle flowers.

There was

nothing on earth I wanted to possess.

I knew no

one worth my envying him.

Whatever

evil I had suffered, I forgot.

To think

that once I was the same man did not embarrass me.

In my body I

felt no pain.

When

straightening up, I saw the blue sea and sails.

Berkeley, 1971

Bài này GCC dịch rồi, nhưng không làm sao kiếm ra!

Thấy rồi! Nó nằm trong bài viết về nhà văn vô lại NV: Viết lại Truyện Kiều

Một ngày thật hạnh phúc

Sương tan sớm, tôi làm vườn

Chim đậu trên cành

Đếch có cái gì trên mặt đất mà tôi muốn sở hữu

Đếch biết 1 ai xứng đáng cho tôi thèm

Cái Ác, bất cứ gì gì, mà tôi đã từng đau khổ, tôi quên mẹ mất rồi.

Nghĩ, có thời, tôi cùng là 1 người, cũng chẳng làm phiền tôi.

Trong thân thể tôi, tôi không cảm thấy đau

Khi ngẩng đầu lên, đứng thẳng dậy, tôi nhìn thấy biển xanh và những

cánh buồm.

Berkeley, 1971.

Milosz là 1 nhà thơ mà cái phần cực độc, cực ác, không thua bất cứ ai, có thể nói như vậy. Suốt đời, ông thèm được như Brodsky, sống 1 cuộc đời gần như sống 1 phép lạ. Nhưng sau ông nhận ra, chính cái phần nhơ bẩn ác độc, với ông, cần hơn nhiều, so với “thiện căn”.The cloaca of the world. A

certain German wrote down that definition of Poland

in 1942. I spent the war years there and afterward, for years, I

attempted to

understand what it means to bear such an experience inside oneself. As

is well

known, the philosopher Adorno said that it would be an abomination to

write

lyric poetry after Auschwitz, and the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas gave

the

year 1941 as the date when God "abandoned" us. Whereas I wrote

idyllic verses, "The World" and a number of others, in the very

center of what was taking place in the anus mundi, and not by any means

out of

ignorance. Do I deserve to be condemned for this? Possibly, it would be

just as

good to write either a bill of accusation or a defense. Horror is the

law of

the world of living creatures, and civilization is concerned with

masking that

truth. Literature and art refine and beautify, and if they were to

depict

reality naked, just as everyone suspects it is (although we defend

ourselves against

that knowledge), no one would be able to stand it. Western Europe can

be

accused of the deceit of civilization. During the industrial revolution

it

sacrificed human beings to the Baal of progress; then it engaged in

trench

warfare. A long time ago, I read a manuscript by one Mr. Ulrich, who

fought at

Verdun as a German infantry soldier. Those people were captured like

the prisoners

in Auschwitz, but the waters of oblivion have closed over their torment

and

death. The habits of civilization have a certain enduring quality and

the

Germans in occupied Western Europe were obviously embarrassed and

concealed

their aims, while in Poland they acted completely openly.

It is

entirely human and understandable to be stunned by blatant criminality

and to

cry out, "That's impossible!" and yet, it was possible. But those who

proclaim that God "abandoned us in 1941" are acting like conservators

of an anodyne civilization. And what about the history of humankind,

with its

millennia of mutual murder? To say nothing of natural catastrophes, or

of the plague,

which depopulated Europe in the fourteenth century.

Nor of those

aspects of human life which do not need a grand public arena to display

their

subservience to the laws of earth.

Life does

not like death. The body, as long as it is able to, sets in opposition

to death

the heart's contractions and the warmth of circulating blood. Gentle

verses

written in the midst of horror declare themselves for life; they are

the body's

rebellion against its destruction. They are

carmina, or incantations deployed in order that the horror should

disappear

for a moment and harmony emerge-the harmony of civilization or, what

amounts to

the same thing, of childish peace. They comfort us, giving us to

understand

that what takes place in anus mundi is transitory, and that harmony is

enduring-which is not at all a certainty.

Milosz cho biết chính là ở

hậu môn thế giới mà ông làm thơ, và đừng có nghĩ là ông

không biết câu phán của Adorno: As is well known, the philosopher

Adorno said

that it would be an abomination to write lyric poetry after Auschwitz,

and the

philosopher Emmanuel Levinas gave the year 1941 as the date when God

"abandoned" us. Whereas I wrote idyllic verses, "The World"

and a number of others, in the very center of what was taking place in

the anus

mundi, and not by any means out of ignorance.

*

Milosz biết,

nhưng nhà nghệ sĩ Võ Đình của Mít, không.

Ông bỏ nước ra đi nên chẳng hề biết

chiến tranh Mít, nhưng lạ là cũng chẳng biết Lò Thiêu, hay Adorno là

thằng chó

nào.

Khi Gấu lỡ nhắc đến thằng chó Adorno, trên tờ Văn Học, khi còn giữ mục Tạp

Ghi, và câu phán ghê gớm của ông, nhà nghệ sĩ bèn mắng, thằng cha này

đúng là

"vung tay quá trán".

Sau Lò Thiêu vẫn có thơ, chứng cớ là "Đêm Tận Thất Thanh" của

Phan Nhật Nam đây nè!

Mà, đâu chỉ... "Đêm Tận

Thất Thanh"!

Có thể nói, tất cả văn chương Mít, sau 30 Tháng Tư 1975, VC hay không VC, tù VC hay không tù VC, thì đều được viết ra, như thể Lò Cải Tạo đếch xẩy ra.

NQT

Văn Học số Xuân Đinh Sửu [129&130],

trong phần Tạp Ghi, ông Nguyễn Quốc Trụ viết: "... rằng sau Auschwitz,

'nếu cá nhân nào đó mà còn làm được thơ thì thật là dã man' (sic), và

'mọi văn hóa sau Auschwitz chỉ

là rác rưởi'.

Tôi chưa từng được quen

biết, trong lãnh vực văn học, ông Adorno này, nên không lạm bàn rông

rài. Chỉ "trộm" nghĩ rằng câu nói của ông [ta] có vẻ như... "vung tay

quá trán". Có thể đổi được chăng những câu phê phán này thành... "sau Auschwitz mà còn làm thơ... Trời ơi, Tuyệt!"?

Hay là, "Mọi văn hóa sau Auschwitz là

những nhánh kỳ hoa bung lên từ bãi dơ bầy nhầy, ruồi nhặng sâu bọ lúc

nhúc, thối um"?

Đêm Tận Thất Thanh là một

nhánh kỳ hoa đó.

.....

Tôi không may mắn

từng đọc tác giả Adorno nói trên....

Loxahatchee, Florida 5-2-97

24 tiếng trước Tết Đinh

Sửu, ở Việt Nam

Võ Đình

Trên đây trích từ bài viết của Võ Đình, ở cuối cuốn Đêm Tận Thất Thanh của "bạn ta" là Phan Nhật Nam. Trong cuốn sách bạn ta tặng, buổi tối tại nhà Nguyễn Đình Thuần. Với lời đề tặng:

Của Ông

Sơ Dạ Hương với tình thân 30 năm Nguyễn Quốc Trụ, La Pagode.

CA Oct/28/2003.

PNN ký tên.

Những bài thơ gởi đảo xa & trăng màu hồng

Sáng nay, trong email Cường lại gởi cho những

tài liệu về Thanh Tâm Tuyền (TTT) trong đó chứa những điều mình chưa

từng biết, những điều lần đầu tiên được công bố. Về một mối

tình và những bài thơ cho đảo xa.

Blog PV

GCC thắc mắc: Ai cho phép mà lần đầu tiên

được công bố?

Thư riêng, mail riêng, làm sao dám đăng lên, rồi tự cho phép lần đầu

tiên được công bố?

NQT

TV đã từng viết về những

kỷ niệm thật riêng tư về TTT, tính, qua đó, lần ra những liên hệ với

những bài thơ, bài viết, truyện ngắn, truyện dài của ông, nhưng sau đó,

nhận được mail của bạn C ra lệnh ngưng.

*

Một bạn văn vừa cho biết nguồn của những bài thơ của TTT.

Tks. NQTThư Tín

From:

Sent: Tuesday, February 14, 2012 5:43 PM

Subject:

tinvan.net

<

GCC thắc mắc: Ai cho phép mà lần đầu tiên được công bố?

Thư riêng, mail riêng, làm sao dám đăng lên, rồi tự cho phép lần đầu

tiên được công bố?

>

Ong

GCC nay qua la bop

chop (as always)

Trong cai link chinh inh o post cua ong GCC : "Giờ đây, sau khi nha tho

nằm xuống sáu năm, tất cả được công bố. Mà do người tình trăng hồng hạ

kia." (http://phovanblog.blogspot.com/)

Thi "nguoi tinh hong ha" cong bo "thu rieng" . The

ong GCC phan doi a ? Ai noi ong "thu rieng khong

dam (sic) dang len" ? Nha tho...cung la mot "public

figure" trong pham tru VN . Dang len cung ...OK lam chu

nhi !

Ong la ai cua nha tho ...qua't la'o the ?

Ong bat duoc "nguon" roi , co phan ung gi chang nhi ?

Phuc đap:

Ban hieu lam roi

...

Phu nhan của nha tho la

nguoi khong lien quan den “giang ho, gio tanh mua mau” (1)

NXT la ban cua TTT

Anh phai biet chuyen do

O dau post cung duoc

Nhung Pho Van dung nen post

Regards

NQT

xin loi ong

GCC .

Bay gio la "mode" tung ...thu* rieng len mang, nguoi doc "net" binh

thuong nhu toi cung nga'n , nhu kieu Dao Anh-TCS ...bay gio "Cu*?a

Kho'a Trai' " - "Trang Hong" - va Nha Tho Tu Do vi dai cua Mien Nam !

Do la thu* / tho* trong tinh tha^`n van nghe , mot kieu lang mang ngoai

doi song ...gia dinh (von khong lang mang cua TTT).

Toi dong y ve post cua ong ve NXT .

Tran trong va xin loi lam phien

Take Care

NQT

(1)

Cái câu của

bà vợ Trung Uý Kiệt, trong Một Chủ

Nhật Khác, có thể áp dụng ở đây:

-Mấy người

không thấy là mấy người diễn trò dâm loàn, đồi bại...

Thùy bật la lên, chụp lấy

Kiệt xâu xé. Kiệt chết sững, không phản ứng. Thùy rít lên: Đồ tồi bại,

đốn mạt, sadique... tu es sadique, không ngờ, không tưởng tượng

nổi. Tởm, tởm quá. Kiệt chảy nước mắt những vẫn cười nôn.

Khi nguôi ngoai, Thùy hỏi:

-Có thật đàn ông các anh ngấm ngầm đều ưa những trò tồi bại? Có thật

anh chán tôi, vì tôi không thể... bước vào khách sạn, hay nằm ngoài

trời với anh như....

-Đừng bậy. Anh không phải thế....

-Thế anh là thế nào? Còn vết sẹo kia giải thích thế nào?...

Kiệt nghẹn

lời. Chàng không thể hé môi. Làm cách nào chàng có thể mở miệng giải

thích?

Rồi cũng qua.

Bây giờ, Kiệt tự đùa mình: một hôm nào tình cờ người tình cũ của ta có

thể đột ngột xuất hiện chăng? Chàng hơi trợn trước câu hỏi.

Source

Đọc lại, và đọc những "lần đầu công bố", thì GCC mới hiểu, Kiệt, có thể đã tính ra được chuyện người tình cũ đột ngột xuất hiện, ở nhà 1 bà bạn, ở Đà Lạt, mà có lẽ luôn cả chuyện vừa mới xẩy ra, và đây là những lời tạ lỗi, tự coi thường chính mình, trước Thùy?

-Anh sa sút thật. Anh sa sút đến em cũng

không ngờ.

Kiệt muốn sa nước mắt sau câu nói của Thùy. (1)

Trên Tin Văn

đã từng trang trọng giới thiệu thơ NXT (1)

Lần mới qua Cali, có gặp ông. Gấu ngồi bàn với ai… nhỉ,

quên mất, ông ghé bắt tay ông bạn ngồi cùng bàn, nhưng

vờ Gấu!

Cũng được.

Quá được là đàng khác!

NQT

Simone Weil

Susan Sontag Tưởng niệm 7 năm TTT mất

Coetzee nói

về Brodsky: Ông chẳng hề loay hoay hì hục

làm cho mình được yêu, thí dụ, như Pasternak, rất được yêu. Venclova

cho rằng,

người Nga tìm chẳng thấy, ở trong thơ của ông sự "ấm áp", "tha

thứ tất cả", "sướt mướt", "nức nở con tim", hay sự

"vui tươi, nhí nhảnh". Nhà thơ Viktor Krivulin nghi ngờ tính hài hước,

rất ư là không giống Nga, very un-Russian, vốn trở thành thói quen

trong thơ

Brodsky. Ông trau giồi hài hước, Krivulin nói, để bảo vệ mình, từ những

ý nghĩ,

tư tưởng, hay hoàn cảnh mà ông cảm thấy không thoải mái. "Một sự sợ hãi

phải

phơi lòng mình ra, hay có thể, chỉ là một ước muốn đừng phơi mở...".

*

Thực sự, trước

1975, TTT không phải là một nhà thơ được nhiều người yêu mến.

Chính vì vậy,

sự bàng hoàng, cơn chấn động ở hải ngoại, khi nghe tin ông mất, chỉ có

thể giải

thích: Chính sự tiết tháo, cương trực, không khoan nhượng với cả chính

mình

không kiếm cách làm cho mình được yêu mến... hay ngắn gọn, chính cái sự

quá sạch

của ông, lại trở thành niềm tin cho tất cả mọi người!

Và như thế,

ông lại giống... Solzhenitsyn, ông này

suốt một đời khổ hạnh, làm việc như trâu, không cho mình bất cứ một cơ

hội nào

bị sa ngã, bị dụ dỗ... bởi cái ác.

Solz cho rằng,

chỉ có cách đó, để không bao giờ phản bội những người bạn tù của ông.

A collection of interviews with Brodsky, Reszty nie trzeba [Keep the Change], in Jerzy Illg's translation, is a constant source of wonderment for me. Just to think how much he had to leave out – what for others was very essence of the 20th century: Marxism-Leninism, Sovietism, nationalism, Nietzscheanism, Freudianism, Surrealism, as well as a dozen or two other isms.

He could have become a dissident, engage, like his friend Tomas Venclova. He could have thought about reforming the state. He could have written avant-garde poems. He could have been a Freudian. He could have paid homage to structuralism. Nothing of the sort.

Life as a moral fable. The poet imprisoned and condemned by the state, then sent into exile by the state, and after his death, the head of that state kneeling beside his coffin. A fairy tale, yet it did happen like that, in our hardly fairy-tale-like century.

He spoke as

one who has authority. Most likely in his youth he was unbearable

because of

that self-assurance, which those around him must have seen as

arrogance. That

self-assurance was a defense mechanism in his relations with people and

masked

his inner irresolution when he felt that he had to act that way, and

only that

way, even though he did not know why. Were it not for that arrogance,

he would

not have quit school. Afterward, he often regretted this, as he himself

admitted.

During his trial, someone who was less self-assured than he was could

probably

not have behaved as he did. He himself did not know how he would

behave, nor

did the authorities foresee it; rather, they did not anticipate that,

without

meaning to, they were making him famous.

Milosz

Chẳng

đợi ông

nằm xuống, khi ông ở tù VC là bạn quí, kẻ thù đã kể như ông chết rồi.

Khi "đảo

xa" tung hê thư tình viết riêng cho ẻn, thì bạn quí bèn xì 1 cú, tưởng

tay này đàng

hoàng đâu ngờ cũng bồ nhí bồ nhiếc.

Đau 1 cái là ngay từ khi còn sống, khi viết

thư cho em, là ông đã nghi, vì đọc, người tinh ý ngửi ra giọng gượng

gạo.

Đau thật!

Về cái khoản

này, ông anh thua thằng em. Gấu Cái kệ mẹ Gấu Đực tán tỉnh hết em này

đến em khác.

Toàn “bản nháp” không hà, hà hà! Bản đích thực, về tui, thằng chả không

đủ tâm,

tầm, tài, hay cái con khỉ gì nữa, để mà viết ra!

Nhớ Già Ung *

Gửi MT

Sáng nay thức

giấc trong nhà giam

Anh nhớ những

câu thơ viết thời trẻ

Bừng cháy trong lòng anh bấy lâu

u ám quạnh

quẽ

Ánh lửa mênh

mang buổi tình đầu

Mưa bụi rì rào

Gió náo nức

mù tối

Trễ muộn mùa xuân trên miền cao

Đang lay thức

rừng núi biên giới

Đã qua đã

qua chuỗi ngày lạnh lẽo anh tự nhủ

Cũng qua cơn

khô hạn khác thường

Tắt theo ngọn

nắng chon von mê hoặc

đầu óc quái

gở

Từng thiêu đốt

anh trên đồi theo vào đêm

hành hạ anh

đớn đau

Từ bao giờ

anh đứng trân trối cô đơn

Hôn ám trời

sơ khai nhìn qua song tù ngục

Hoang vu lời

thơ ai reo hát cùng cỏ lá heo hút

Dẫn đưa anh

về tận nẻo nguồn

chốn bình

minh lẩn lút

(Bình minh

bình minh anh kêu khẽ cảm động muốn khóc

Mai Mai xa

Mai như hoa Mai về

tình thơ hôm

nay)

Em, em có

hay kẻ tội đồ biệt xứ

sớm nay về

ngang cố quận

Xao xuyến

ngây ngô hắn dọ hỏi bóng tối sâu thẳm

Đêm vây hãm

lụn dần

Thủ thỉ mưa

ru ngày khốn đốn

Em, soi bóng

em hồn nhiên trên lối thời gian

Lặng lẽ anh

gầy nhóm lửa tinh mơ đầm ấm.

Lào Kay 4/78

Vĩnh Phú

1/79

Thanh Tâm Tuyền

Bài thơ, bây giờ đọc lại, thì lại quá mê cái dòng tặng Mai Thảo:

Trong tôi còn lại chi? Gia đình, bạn bè. Những bài thơ, chắc chắn rồi. Chúng đã được đọc, được thầm ghi lại (intériorisés). Đúng một lúc nào đó, ký ức nhanh chóng bật dậy, đọc, cho riêng mình tôi, những bài thơ. Luôn luôn, ở đó, bạn sẽ gặp những tia sáng lạ. Thời gian của điêu tàn làm mạnh thơ ca.

Thơ giữa Chiến Tranh và Trại TùREADING THE

NOTEBOOK OF

ANNA

KAMIENSKA

Reading her,

I realized how rich she was and myself, how poor

Rich in love

and suffering, in crying and dreams and prayer.

She lived

among her own people who were not very happy but

supported

each other,

And were

bound by a pact between the dead and the living renewed

at the

graves.

She was

gladdened by herbs, wild roses, pines, potato fields

nd the

scents of the soil, familiar since childhood.

She was not

an eminent poet. But that was just:

A good

person will not learn the wiles of art.

Đọc Sổ Ghi của Anna Kamienska (1)

Đọc bà, tôi

nhận ra bà giầu biết bao, còn tôi, nghèo làm sao.

Giầu có

trong tình yêu, và đau khổ, trong than khóc và mơ mộng, cầu nguyện .

Bà sống giữa

những con người của riêng bà, không rất hạnh phúc, nhưng giúp đỡ lẫn

nhau,

Và được gắn

bó bằng 1 hợp đồng giữa người chết và người sống được làm mới ở những

nấm mồ.

Bà thì thật vui với cỏ, hoa, thông, cánh đồng khoai tây

Và mùi của đất,

quen thuộc từ khi còn là con nít.

Bà không phải

là 1 nhà thơ uyên bác. Nhưng đúng là như thế này:

Một con người

tốt sẽ không học những mưu ma chước quỉ của nghệ thuật.

GIFT

A day so

happy.

Fog lilted

early, I worked in the garden.

Hummingbirds

were stopping over honeysuckle flowers.

There was nothing

on earth I wanted to possess.

I knew no one

worth my envying him.

Whatever evil

I had suffered, I forgot.

To think that

once I was the same man did not embarrass me.

In my body I

felt no pain.

When straightening

up, I saw the blue sea and sails.

Một ngày thật hạnh phúc

Sương tan sớm, tôi làm vườn

Chim đậu trên cành

Đếch có cái gì trên mặt đất mà tôi muốn sở hữu

Đếch biết 1 ai xứng đáng cho tôi thèm

Cái Ác, bất cứ gì gì, mà tôi đã từng đau khổ, tôi quên mẹ mất rồi.

Nghĩ, có thời, tôi cùng là 1 người, cũng chẳng làm phiền tôi.

Trong thân thể tôi, tôi không cảm thấy đau

Khi ngẩng đầu lên, đứng thẳng dậy, tôi nhìn thấy biển xanh và những

cánh buồm.

Berkeley, 1971.

Milosz là 1 nhà thơ mà cái phần cực độc, cực ác, không thua bất cứ ai, có thể nói như vậy. Suốt đời, ông thèm được như Brodsky, sống 1 cuộc đời gần như sống 1 phép lạ. Nhưng sau ông nhận ra, chính cái phần nhơ bẩn ác độc, với ông, cần hơn nhiều, so với “thiện căn”.“Where your pain is, there your heart lies also.” (2)

― Anna Kamieńska

TREATISE ON THEOLOGY

1. A YOUNG MAN

A young man

couldn't write a treatise like this,

Though I

don't think it is dictated by fear of death.

It is,

simply, after many attempts, a thanksgiving.

Also,

perhaps, a farewell to the decadence

Into which

the language of poetry in my age has fallen.

Why theology? Because the first must be first.

And first is

a notion of truth. It is poetry, precisely,

With its

behavior of a bird thrashing against the transparency

Of a

windowpane that testifies to the fact

That we

don't know how to live in a phantasmagoria.

Let reality

return to our speech.

That is,

meaning. Impossible without an absolute point of reference.

Luận về Thần Học

1.Một thanh niên

Một thanh niên

không thể viết một luận đề như thế này

Tuy nhiên, tôi

không nghĩ, nó được viết ra bởi nỗi sợ chết.

Sau nhiều lần

toan tính, nó giản dị là một lời tạ ơn.

Có lẽ, nó còn

là một lời vĩnh biệt sự suy đồi mà ngôn ngữ thơ thời đại tôi sa vào.

Tại sao thần học? Bởi là cái đầu tiên phải là cái đầu tiên.

Và cái đầu

tiên, đó là, một ý niệm về sự thực. Nó là thơ, chính xác là vậy,

Với ứng xử của

một con chim đập vô cái trong suốt của kính cửa sổ,

Nó chứng thực

một sự kiện là,

Chúng ta đếch

biết làm thế nào sống ở trong cái gọi là “ảo giác”.

Hãy để thực

tại trở về với lời nói của chúng ta.

Nói như vậy

có nghĩa là, ý nghĩa.

Thật vô phương,

nếu không có điểm qui chiếu khởi đầu tuyệt đối.

2. A POET WHO WAS BAPTIZED

A poet who

was baptized

in the

country church of a Catholic parish

encountered

difficulties

with his

fellow believers.

He tried to

guess what was going on in their heads.

He suspected

an inveterate lesion of humiliation

which had

issued in this compensatory tribal rite.

And yet each

one of them carried his or her own fate.

The opposition, I versus they, seemed immoral.

It meant I

considered myself better than they were.

It was easier to repeat the prayers in English

at the

Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Berkeley.

Once,

driving on the freeway and coming to a fork

where one

lane leads to San Francisco, one to Sacramento,

He thought

that one day he would need to write a theological

treatise

to redeem

himself from the sin of pride.

The earth is not a dream but living flesh,

That sight, touch, and hearing do not lie,

That all things you have ever seen here

Are like a garden looked at from a gate.

You cannot enter. But you're sure it's there.

Could we but look more clearly and wisely

We might discover somewhere in the garden

A strange new flower and an unnamed star.

Some people say we should not trust our eyes,

That there is nothing, just a seeming,

These are the ones who have no hope.

They think that the moment we turn away,

The world, behind our backs, ceases to exist,

As if snatched up by the hands of thieves.

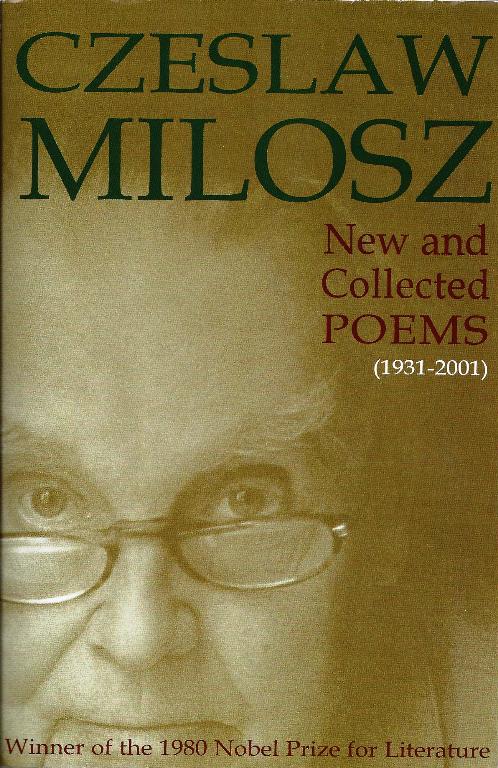

Czeslaw Milosz: New and Collected Poems

V.

I was very young when I first felt depressed by the idea of eternally existing matter,

And of time stretching backward and forward forever.

It

contradicted my image of God the Creator,

For what

would he have to do in a universe everlasting?

So I read

"The Letter to Storge" like a revelation,

Learning

that time and space had a beginning,

That they

appeared in a flash together with so-called matter,

Just as

medieval scholars from Oxford to Chartres had guessed,

Through a transmutatio of divine light into light

merely physical.

How much

that changed my poems! They were dedicated

to the contemplation of time

Behind

which, since that moment, eternity transpired.

Though I was

dissatisfied with my writing, which was provisional,

Namely, of

that kind in which what is most important remains

hidden.

Of course, I

was guilty of folly and trespasses.

I pronounced

the name of a woman and it seemed she was standing

by.

And yet I

could not make a confession of my life,

For good and

evil were too deeply entangled in my egoistic oeuvre.

Czeslaw

Milosz: Second Space

"The Letter to Storge": This poem puts forth the hypothesis that universe originated in an unimaginable flash that gave birth to space, time, and matter. Many decades later the same hypothesis was advanced in the form of the Big Bang Theory.

As medieval scholars ... had guessed: Scholars from Oxford and Chartres maintained that before the creation of the world there was nonphysical divine light. God's Fiat lux was a transmutation of this nonphysical light.

For good and evil were too

deeply

entangled:

The

creation of works of art is marked by an astonishing duality: on the

one hand

it is a completely disinterested activity, even altruistic, consisting

of

detaching oneself from oneself; on the other hand it consists in

feeding one's

egoistic ambition. Whenever creative work enters personal life and

makes its

demand there, honest self-examination is very difficult. An oeuvre does

not

exonerate. And yet it is not quite "egoistic," though it introduces

into a life many complications.

V.

Khi còn cực

trẻ, lần đầu tiên tôi bị hỏng cẳng,

Đó là khi đụng ý tưởng, về 1 thứ "vật chất" thiên thu bất diệt.

Và về thời

gian ngược xuôi hoài hoài, vô tư, thoải mái.

Nó chửi bố hình

ảnh Đấng Sáng Tạo

Ông ta làm cái

chó gì trong vũ trụ hoài hoài đó?

Bởi vì thế mà

tôi đọc “Thư gửi Storge” như 1 mặc khải,

Biết ra rằng

thì là thời gian và không gian thì có bắt đầu.

Rằng chúng

xuất hiện cùng trong cú chớp với cái gọi là vật chất,

Đúng như là

những nhà học giả trung cổ từ Oxford tới Chartres dự đoán,

Qua một “transmutation”, ánh sáng thiêng liêng biến thành ánh sáng đơn

thuần vật chất.

Ui chao nó mới

thay đổi những bài thơ của tôi!

Chúng được đề

tặng sự chiêm ngưỡng thời gian

Đằng sau nó,

kể từ khoảnh khắc đó, thiên thu “tiết lộ”.

Tuy nhiên tôi

vưỡn đếch hài lòng với những gì tôi viết ra.

Chúng mới tàm tạm, đường được làm

sao!

Thì nói mẹ

ra ở đây: Trong đó, cái quan trọng nhất thì lại bị giấu kín!

Lẽ dĩ nhiên,

tôi cảm thấy tội lỗi, vì khùng điên ba trợn, và báng bổ, xúc phạm

Tôi đọc tên BHD, thế là nàng đứng kế bên tôi!

Tuy nhiên, tôi

vưỡn không làm sao làm 1 cú thú tội về đời mình

Bởi là vì

thiện và ác thì cắm rễ thật là sâu ở trong thằng cu Gấu Bắc Kít,

ích kỷ tàn nhẫn

không biết thương yêu vợ con, ngày nào!

Note: Bài thơ này, khi dịch & post, Gấu quên không đề tên tác giả, Milosz

Nè, tên thi sỡi kia, mi

làm cái trò gì ở đây,

Trên những điêu tàn của Nhà Thờ St. John

Vào một ngày xuân đẹp nắng như thế này?

Mi nghĩ gì, vào lúc này,

khi gió đùa về đây,

Từ những nát tan ở khu Vistula,

Bụi đỏ của đá vụn

Mi thề, mi đếch bao giờ

làm một kẻ khóc lóc, than thở theo đúng lễ nghi

Mi thề mi chẳng bao giờ rờ vô

những vết thương sâu hoắm của nước Mít của mi.

Bởi vì nếu khóc than như thế là mi biến chúng thành thiêng liêng

Thứ thiêng liêng đặc biệt Mít, rất ư khó chịu, thứ thiêng liêng chết

tiệt,

Đeo đuổi dân Mít từ thuở dựng nước cho tới bi giờ.

Nhưng sự than thở của

Antigone

Dành cho người anh của nàng

Thì vượt quá cả quyền uy của sự bền bỉ chịu đựng.

Và trái tim thì là 1 hòn đá,

trong đó có một tình yêu u tối, như côn trùng,

Của một miền đất cực kỳ bất hạnh.

Gấu đếch muốn yêu nước Mít

bằng thứ tình yêu cà chớn đó.

Đó không phải là sở nguyện của Gấu.

Gấu cũng đếch muốn thương hại kiểu đó.

Cũng đếch phải sơ đồ của Gấu

Cây viết của Gấu thì nhẹ hơn nhiều.

Nhẹ hơn cả một cái lông… chim!

Thứ gánh nặng đó, quá nặng cho nó,

Để mà mang, khiêng, chịu đựng.

Làm sao Gấu sống ở xứ đó

Khi bàn chân, đi tới đâu, là đụng tới xương của họ hàng, bà con,

Những người không được chôn cất.

Gấu nghe những tiếng nói, nhìn thấy những nụ cười.

Gấu không thể viết bất cứ

điều gì; năm bàn tay

nắm lấy cây viết của Gấu và ra lệnh viết

Câu chuyện về cuộc đời và cái chết của họ.

Không lẽ Gấu sinh ra

để là 1 tên khóc than theo nghi lễ, Nhà Thờ, hay Cửa Phật?

Gấu muốn hát về những lễ hội.

Về cánh rừng xanh mà Shakespeare

thường rủ Gấu vô đó chơi.

Hãy để thi sĩ cho một khoảnh khắc hạnh phúc,

nếu không, thế giới của bạn sẽ tiêu tùng.

Đúng là khùng điên, ba

trợn,

Nếu sống mà đếch vui, đếch thú, đếch sướng gì hết!

[Hà, hà!]

Và lập lại những người đã chết

Lập cái cái phần vui vẻ, sung sướng hạnh phúc của hành động,

Trong tư tưởng, trong thân xác còn tươi rói, trong hát hỏng, lễ hội.

Chỉ hai từ cứu rỗi:

Sự thực và công lý

Note: Leave

To poets a moment of happiness,

Otherwise your world will perish.

[Lâu lâu phải cho Gấu tự thổi, nhe!]

What are you doing here,

poet, on the ruins

Of St. John's Cathedral this sunny

Day in spring?

What are you thinking

here, where the wind

Blowing from the Vistula scatters

The red dust of the rubble?

You swore never to be

A ritual mourner.

You swore never to touch

The deep wounds of your nation

So you would not make them holy

With the accursed holiness that pursues

Descendants for many centuries.

But the lament of Antigone

Searching for her brother

Is indeed beyond the power

Of endurance. And the heart

Is a stone in which is enclosed,

Like an insect, the dark love

Of a most unhappy land.

I did not want to love so.

That was not my design.

I did not want to pity so

That was not my design

My pen is lighter

Than a hummingbird's feather.

This burden

Is too much for it to bear.

How can I live in this country

Where the foot knocks against

The unburied bones of kin?

I hear

voices, see smiles. I cannot

Write anything; five hands

Seize my pen and order me to write

The story of their lives and deaths.

Was I born to become

a ritual mourner?

I want to sing of festivities,

The greenwood into which Shakespeare

Often took me. Leave

To poets a moment of happiness,

Otherwise your world will perish.

It's madness to live

without joy

And to repeat to the dead

Whose part was to be gladness

Of action in thought and in the flesh, singing, feasts,

Only the two salvaged words:

Truth and justice.

Warsaw, 1945

Nè, tên thi sỡi kia, mi

làm cái trò gì ở đây,

Trên những điêu tàn của Nhà Thờ St. John

Vào một ngày xuân đẹp nắng như thế này?

Mi nghĩ gì, vào lúc này,

khi gió đùa về đây,

Từ những nát tan ở khu Vistula,

Bụi đỏ của đá vụn

Mi thề, mi đếch bao giờ

làm một kẻ khóc lóc, than thở theo đúng lễ nghi

Mi thề mi chẳng bao giờ rờ vô

những vết thương sâu hoắm của nước Mít của mi.

Bởi vì nếu khóc than như thế là mi biến chúng thành thiêng liêng

Thứ thiêng liêng đặc biệt Mít, rất ư khó chịu, thứ thiêng liêng chết

tiệt,

Đeo đuổi dân Mít từ thuở dựng nước cho tới bi giờ.

Nhưng sự than thở của

Antigone

Dành cho người anh của nàng

Thì vượt quá cả quyền uy của sự bền bỉ chịu đựng.

Và trái tim thì là 1 hòn đá,

trong đó có một tình yêu u tối, như côn trùng,

Của một miền đất cực kỳ bất hạnh.

Gấu đếch muốn yêu nước Mít

bằng thứ tình yêu cà chớn đó.

Đó không phải là sở nguyện của Gấu.

Gấu cũng đếch muốn thương hại kiểu đó.

Cũng đếch phải sơ đồ của Gấu

Cây viết của Gấu thì nhẹ hơn nhiều.

Nhẹ hơn cả một cái lông… chim!

Thứ gánh nặng đó, quá nặng cho nó,

Để mà mang, khiêng, chịu đựng.

Làm sao Gấu sống ở xứ đó

Khi bàn chân, đi tới đâu, là đụng tới xương của họ hàng, bà con,

Những người không được chôn cất.

Gấu nghe những tiếng nói, nhìn thấy những nụ cười.

Gấu không thể viết bất cứ

điều gì; năm bàn tay

nắm lấy cây viết của Gấu và ra lệnh viết

Câu chuyện về cuộc đời và cái chết của họ.

Không lẽ Gấu sinh ra

để là 1 tên khóc than theo nghi lễ, Nhà Thờ, hay Cửa Phật?

Gấu muốn hát về những lễ hội.

Về cánh rừng xanh mà Shakespeare

thường rủ Gấu vô đó chơi.

Hãy để thi sĩ cho một khoảnh khắc hạnh phúc,

nếu không, thế giới của bạn sẽ tiêu tùng.

Đúng là khùng điên, ba

trợn,

Nếu sống mà đếch vui, đếch thú, đếch sướng gì hết!

[Hà, hà!]

Và lập lại những người đã chết

Lập cái cái phần vui vẻ, sung sướng hạnh phúc của hành động,

Trong tư tưởng, trong thân xác còn tươi rói, trong hát hỏng, lễ hội.

Chỉ hai từ cứu rỗi:

Sự thực và công lý

Warsaw, 1945

Note: Leave

To poets a moment of happiness,

Otherwise your world will perish.

[Lâu lâu phải cho Gấu tự

thổi, nhe!]

11

I often

think of Venice, which returns like a musical motif,

From the

time of my first visit there before the war,

When I saw

on the beach at Lido

The goddess

Diana in the form of a German girl,

To the last

when, after burying Joseph Brodsky,

We feasted

at the Palazzo Mocenigo, the very one

In which

Lord Byron had lived.

And there

were the chairs of the cafés in the Piazza San Marco.

That's where

Oscar Milosz, solitary wanderer,

Came under

sentence in 1909:

He beheld

the love of his life, Emmy von Heine-Geldern,

Whom he

called till the day of his death "my beloved wife,"

And who

married Baron Leo Salvotti von Eichencraft

und

Bindenburg

And died in

Vienna in the second half of the century.

Czeslaw

Milosz

Tôi thường

nghĩ tới Venice, nó trở đi trở lại với tôi như một mô típ nhạc.

Từ cái lần tôi

thăm đầu tiên trước cuộc chiến,

Khi tôi nhìn

thấy ở bãi biển Lido

Vị nữ thần

Diana trong dáng dấp một cô gái Đức

Tới lần cuối,

khi chôn cất Joseph Brodsky,

Chúng tôi tiệc

tùng tại Palazzo Mocenigo, đúng “nơi rất nơi“ mà Lord Byron đã sống.

Và rồi thì có

những cái ghế ở những quán cà phê ở Piazza San Marco.

Đó là nơi mà

Oscar Miloz, kẻ lang thang một mình

Tới, dưới án

tù, vào năm 1909:

Ông nhìn ngắm

tình yêu của đời mình, Emmy von Heine-Geldern,

Người mà ông,

cho đến khi chết, gọi là “người vợ yêu quí của tôi”,

Bà này kết hôn

với Baron Leo Salvotti von Eichencraft

und

Bindenburg

Và mất ở

Vienna vào hậu bán thế kỷ

When I saw on the beach at

Lido: A

beautiful German girl appears in

my "Six Lectures in

Verse" from 1987.

[Cô gái Đức

xinh đẹp xuất hiện trong "Sáu Bài Đọc bằng Thơ" của tôi, 1987]

After burying Joseph

Brodsky:

The body of Joseph Brodsky, who

died in New York City in 1996, was, in accordance with his wishes,

transported

to Venice and buried in the cemetery of San Michele on the twenty-first

of

June, 1997. Paradoxically,

his tomb and the tomb of Ezra Pound are contiguous.

[Sau khi chôn

Joseph Brodsky: Xác thân của Joseph Brodsky, mất tại New York City năm

1996, được

đưa về Venice như ý nguyện của ông, và chôn ở nghĩa địa San Michele vào

ngày 21

Tháng Sáu 1997. Thú vị là hai cái mồ, của ông và của Erza Pound kế bên

nhau.]

We feasted at the Palazzo Mocenigo: Byron stayed there for some time in 1818 and it was there, in the early months of 1819, that he began his Don Juan.

Emmy von Heine-Geldern: She was born in 1890 in Vienna, a younger daughter of Baron Gustav von Heine-Geldern and his wife, Regine, a relation of the poet H inri h Heine. She died in Vienna in the 1960s. o. M. called Emmy his celestial wife. The marriage between them never occurred because of the intrigues of his mother, though we do not know the reasons for her opposition. When Emmy married another man in 1910, O. M. was thirty-three. It is difficult, therefore, to suspect him of bowing to his mother's will.IF THERE IS NO GOD

If there is no God,

Not everything is permitted to man.

He is still his brother's keeper

And he is not permitted to sadden his brother,

By saying that there is no God.

Nếu không có Chúa

Nếu không có Chúa

Không phải chuyện gì con người cũng được phép

Nó vẫn là người chăn giữ thằng em

Và nó đâu được phép làm buồn thằng em

Khi nói không có Chúa

HIGH TERRACES

Terraces high above the

brightness of the sea.

We were the first in the hotel to go down to breakfast.

Far off, on the horizon, huge ships maneuvered.

In King Sigismund Augustus High School

We used to begin each day with a song about dawn.

I

wake to light that warms

My eye

And feel Almighty God

Nearby.

All my life I tried to

answer the question, where does evil come from?

Impossible that people should suffer so much, if God is in Heaven

And nearby.

Sân thượng trên cao

Sân thượng cao hơn cả vùng

sáng của biển

Chúng tôi là những người khách đầu tiên của khách sạn

Đi xuống dùng điểm tâm

Xa tít xa, ở nơi đường chân trời, những con tầu lớn loay

hoay vận hành

Ở trường trung học King Sigismund Augustus High School

Chúng tôi thường bắt đầu mỗi ngày bằng 1 bài hát về rạng đông

Tôi

thức dậy sưởi ấm mắt bằng ánh mặt trời

Và cảm thấy Thượng Đế Cao Cả

Ở ngay kế bên

Cả đời tôi, tôi cố trả lời

câu hỏi, cái ác, cái quỉ ma đến từ đâu

Thật không thể, nếu con người đau khổ như thế đó, mà lại có một đấng

Thượng Đế ở Thiên Đàng

Hay

Ngay kế bên (1)

Czeslaw Milosz: Selected Poems 1931-2004

Kỷ niệm 100 năm sinh của Milosz

The wiles

of art

Mưu ma chước quỉ của nghệ thuật

Guilt and greatness in the life of

Czeslaw Milosz

Tội Lỗi và Sự Lớn Lao trong cuộc đời Czeslaw Milosz

CLARE CAVANAGH

Note:

Bài viết trên TLS, Nov 25, 2011. Clare Cavanagh, chuyên gia tiếng Ba

Lan, giáo

sư Slavic languages tại Đại học North-western University, chuyên dịch

thơ Adam

Zagajewski, Wislawa Szymborska, Czeslaw Milosz. Viết phê bình thơ cũng

bảnh

lắm. Bài viết thật tuyệt, về nhà thơ “bửn”, (1) [wiles of art: mưu ma

chước quỉ

của nghệ thuật] của thế kỷ, và nếu không bửn, chắc gì đã được Nobel văn

chương?

TV sẽ giới thiệu, tiếp theo bài về Brodsky The

Gift

(1)

Đây

là muốn nhắc tới bài viết ngắn “To Wash” của ông.

Hay những dòng thơ sau đây, trong "A Task" (1970):

"I think I would fulfill my life / Only if I brought myself to make a

public confession / Revealing a sham, my own, and that of my epoch"

Tôi nghĩ tôi sẽ làm trọn đời mình/Chỉ bằng cách ra giữa Ba Đình/Làm 1

cú tự

kiểm trước nhân dân/ Nói lên cái nhục nhã của riêng tôi, của thời của

tôi, của

đám sĩ phu Bắc Kít chúng tôi.

Ký tên: HC!

Đọc bài viết

là thể nào cũng nghĩ đến những nhà thơ Bắc Kít của chúng ta, và… TCS:

Với Milosz,

nhục nhã và sức mạnh đi sóng đôi. Như những nơi chốn và ngày

tháng cho thấy – ông sinh

ra ở 1 góc

xa xôi của Đế Quốc Nga vào năm 1911, và chết ở 1 Cracow-hậu CS, vào năm

2004 – ông

là 1 kẻ sống sót. Ông viết để sống sót, và sống sót để viết, nhưng ông

tới từ 1

phần của thế giới ở đó có truyền thống coi nhà thơ- kẻ sống sót thì

rất đáng

ngờ, nếu không muốn nói, đáng tởm: Những quốc gia bị áp bức nuôi dưỡng

truyền

thống Lãng Mạn thích “xoa đầu” kẻ tuẫn nạn hơn là 1 anh già 90 được

Nobel văn

chương!

Một đấng bạn thời chiến nhớ lại, Milosz đã từng nằng nặc phán, “tớ đếch

muốn [lên rừng theo VC], chiến đấu, kể từ khi mà tớ phải sống sót cuộc

chiến:

nhiệm vụ của tớ là viết [làm nhạc phản chiến], chứ không phải là chiến

trận, cái

chết của tớ thì vô ích, trong khi cái viết của tớ thì quan trọng cho Ba

Lan”.

Milosz's shame and his strength go hand in hand. As his dates suggest - he was born in a remote comer of the Russian Empire in 1911 and died in post-Communist Cracow in 2004 - he was a survivor. He wrote to survive, and he survived to write. But he came from a part of the world and a tradition where poet-survivors are suspect: oppressed nations fostered on Romantic traditions favor martyrs over Nobel Prize-winning nonagenarians. A wartime acquaintance recalls Milosz insisting that "he didn't intend to fight since he had to survive the war: his task was writing and not battle, his likely death would serve no purpose, while his writing was important for Poland".

The wiles

of art

Mưu ma chước quỉ của nghệ thuật

Tội Lỗi và Sự Lớn Lao trong cuộc đời Czeslaw

The wiles of art

Guilt and greatness in the life of Czeslaw Milosz

"I am Milosz, I must be Milosz, / Being Milosz, I don't want to be Milosz, / I kill the Milosz in myself so as / To be more Milosz." Witold Gombrowicz's lines describe not only the plight of its famous subject, but the difficulties facing his would-be biographers as well. And Gombrowicz didn't know the half of it. His comment dates from 1952; Czeslaw Milosz had just broken with the Polish Communist government, and was destined to spend what he later called "the hardest decade" of a tumultuous life in exile in France. But he still had more than five decades of self-contradiction ahead of him with which to baffle countrymen and admirers alike.

Czeslawa Milosza autoportret przekorny (1994, Czeslaw Milosz's Perverse Self-Portrait) is the title of a revealing book length series of interviews that the scholar Aleksander Fiut conducted with Milosz between 1979 and 1990. "How did he get me to tell him so much?", the poet later complained. Milosz was notoriously averse to self-revelation. He disdained the confessional strain that dominated so much postwar American poetry: a true poet kept his demons to himself, he insisted. "Whenever Robert Lowell landed in a clinic I couldn't help thinking that if someone would only give him fifteen lashes with a belt on his bare behind, he'd recover immediately", he writes in A Year of the Hunter (1994; Rok mysliwego, 1990). He is more charitable in a late poem. "I had no right to talk of you that way / Robert", he confesses. "I used to walk upright to hide my affliction. / You didn't have to." What was the affliction that plagued Milosz? Concealment and self-reproach run through the later work particularly. "I know that in me are pride, desire, I and cruelty, and a grain of contempt", he writes in an un translated early poem. What might seem the youthful clichés of a poète maudit in the making gain weight through decades of repetition. "This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine", he seems to admit, with Prospero, in the title poem of his collection To (2000, This): "If I could at last tell you what is in me, / If I could shout: people! I have lied by pretending it was not there". But the confession is carefully couched in the conditional: we never find out exactly what "this" is.

"Writing has been for me a protective strategy/Of erasing traces", he explains in the same poem. Friends and admirers have wondered for years: what sins did he spend a lifetime trying to erase? Andrzej Franaszek's magnificently researched Milosz: Biografia, published earlier this year in Poland, gives as close to a definitive answer as we can reasonably hope for. There is no single secret, no hidden crime. The affliction goes hand in hand with the artistry, as "This" suggests: "Only thus was I able to describe your inflammable cities / Brief loves, games disintegrating into dust". And the self-contempt, the "shame of failing to be I What I should have been" ("To Raja Rao", 1969), meets its match in Milosz's deep ambivalence towards the extraordinary body of work he spent a lifetime expanding, revisiting and revising. "What is poetry", he famously asks in "Dedication" (1945): "A connivance with official lies, / A song of drunkards whose throats will be cut in a moment, / Readings for sophomore girls".

The art and the self were never enough. Enough for what? Yet another of Milosz's quasi-confessions provides clues: "I think I would fulfill my life / Only if I brought myself to make a public confession / Revealing a sham, my own, and that of my epoch", he admits in "A Task" (1970). His life and that of his age: the two conjoined in his mind early on. "Who is a poet?", Thomas Mann asks, and the answer he provides might be taken from Milosz's own writings: "He whose life is symbolic". "Tomorrow at the latest I'll start working on a great book [dzielo] / In which my century will appear as it really was", he promises in "Preparation" (1986).

He had in fact begun that book - which would span volumes, genres, nations and decades - much earlier. "Folly, the absurdity of phenomena, theories, beliefs, drives. Of these writing is the least ridiculous. Such is the mood of a young man perfectly prepared to face History", the twenty-two-year-old writer tells his early mentor, the poet Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz, only half-ironically. He directed his aspirations early on to writing the kind of mystical, heterogeneous book (ksiega) he describes in an early essay (1938) on his distant cousin, the French-Lithuanian poet Oscar Milosz: "The Bible ... the Divine Comedy, Faust .... These are books concealing a wisdom as complete as it is possible for a person to attain, books of the initiated". Oscar Milosz, an admirer of Shelley and Byron, adhered to the Romantic notion of the "poet as a legislator of the collective imagination", and his young apprentice followed his lead. Even the difficult decades spent a continent away from his native Lithuania, he wrote a half-century later, answered the prayers of a "boy who read the bards and asked for greatness which means exile" ("The Wormwood Star", 1977-8).

"My life story is one of the most astonishing I have ever come across", Milosz writes in his ABC's (2001; Abecadlo Milosza, 1997-8). This story, as he tells and retells it in the work, is both a spiritual pilgrimage and an extraordinary picaresque. The 959 pages of Franaszek's biography are scarcely enough to tell it. "You can't put it down", friends in Poland told me time and again, and they were right. Milosz "wants to become the biographer of his own talent", a skeptical colleague remarked of the brilliant young poet in interwar Vilnius. He became the biographer of much more; one might follow the poet's own lead in "making of Milosz's biography a tale of initiation, whose hero penetrates all the mysteries of the twentieth century", Franaszek comments.

"My age", "my era", "my epoch", "my century": the phrases punctuate Milosz's later work particularly. The young poet who claimed to be ready for History had no idea.

Even the most abbreviated list of places and names that run through the biography - rural Lithuania, the Tran-Siberian Railway, revolutionary Russia, interwar Paris, Nazi-occupied Warsaw, the Polish Embassy in post-war Washington, DC, Berkeley in 1968, Stockholm in 1980, People's Poland in 1981, post-Communist Poland a decade later, W. H. Auden, Hannah Arendt, Albert Camus, Albert Einstein, T. S. Eliot, Karl Jaspers, Thomas Merton, Pablo Neruda, Ronald Reagan, Jean-Paul Sartre, Paul Valery, Lech Walesa, Karol Wojtyla - reads like a Who's Who, and a Where's Where, of the century just past. And this is to say nothing of the less recognizable human histories Milosz carefully preserved from anonymity: "Still in my mind [I try] to save Miss Jadwiga", he writes of one wartime recollection:

A little hunchback, librarian by profession, Who perished in the shelter of an apartment house That was considered safe but toppled down And no one was able to dig through the slabs of wall, Though knocking and voices were heard for many days. ("Six Lectures in Verse", 1985).

That knocking and those voices haunt the poetry and prose alike.

Milosz's shame and his strength go hand in hand. As his dates suggest - he was born in a remote comer of the Russian Empire in 1911 and died in post-Communist Cracow in 2004 - he was a survivor. He wrote to survive, and he survived to write. But he came from a part of the world and a tradition where poet-survivors are suspect: oppressed nations fostered on Romantic traditions favor martyrs over Nobel Prize-winning nonagenarians. A wartime acquaintance recalls Milosz insisting that "he didn't intend to fight since he had to survive the war: his task was writing and not battle, his likely death would serve no purpose, while his writing was important for Poland". His decision to sit out the Warsaw Uprising against the Nazis another great poet, Krzysztof Kamil Bacczynski, died on the barricades at the age of twenty-three - still provoked heated arguments at recent centennial events in Poland. His brief affiliation with the Soviet-backed government after the war - though he never became a Party member - haunted him to the end. I remember him agonizing, in 2002, over a younger poet's charge that he had spent the post-war years as "Moscow's dancing bear".

His break with the Party in 1951 was no less controversial. "But you're a deserter. / But you're a traitor": the poet Konstanty Galczynski voiced the party line in his notorious "Epic for a Traitor" (1953). Milosz became an official non-person in People's Poland shortly thereafter. The situation in Paris was not much better. The émigré community despised the former sympathizer, while pro-Soviet intellectuals such as Sartre spurned the apostate. The uprising, the Communist takeover, the break with the regime, and an uncertain exile: these traumas initiated a remarkably productive decade that saw the making of Milosz's international reputation with the publication of his classic Captive Mind (Zniewolony umyst, 1953), as well as essays, two novels, his volume Swiatlo dzienne (1953, Daylight) and his Treatise on Poetry (Traktat poetycki, 1957). The periodic "Milosz affairs" that punctuated his life seem to have spurred his already formidable creative energies.

In his later writings, Milosz often casts himself as Foolish Jack, the younger brother in the fairy tales who muddles every move, but marries the king's daughter in the end. He found an even less likely alter ego in his later years. "You cannot write my biography!" he told me two years before his death (he had already authorized me to do an English-language version). "But it's too late!" I told him, shocked. "I've already spent the advance!" "Then you must make it a comedy", he responded. "It's the story of Forrest Gump." I'd handed him the set-up he'd been waiting for, and he roared at his own joke.

His life had been shaped, so he thought, by luck or fate: "Perhaps I was born so that the 'Eternal Slaves' might speak through my lips", he intones near the end of Captive Mind. For his less forgiving countrymen, at home and abroad, egotism and opportunism were common charges. How had he managed to land on his feet time and again? International success, a long, complicated life, and an irresistible impulse to play the gadfly meant that even his triumphal return to Poland in his last years met with mixed reactions. Fireworks over Cracow's Wawel Castle marked his ninetieth birthday. On a smaller scale, a taxi driver gasped when he recognized Milosz's home from the street address I gave him a year later. "He hasn't been feeling well, has he?", he asked, and passed on best wishes from the "cabbie in the red Mercedes". But Milosz's public support for a local gay rights parade shortly before his death led to yet another round of pro-Communist and anti-Catholic charges, charges that resurfaced as his family struggled to have him buried in the Paulinist Crypt in Cracow. The official government announcement of the current "Year of Milosz" sparked further protests. "What are you going to see him for?" a ticket-taker scornfully asked one recent visitor to the tomb.

"How could he do it? Knowing what we know / About his life, every day aware / Of harm he did to others", Milosz writes in "Biography of an Artist" (1995). He may have seemed fate's undeserving favorite to many compatriots, and to himself at times. But a darker model also shaped his vision of his life in art. "I have not progressed, in my religion, beyond the Book of Job, / With the one difference that Job saw himself as innocent", he confesses in "A Treatise on Theology" (2002). Job's family was punished for his righteousness, while Milosz' s family paid the price, so he thought, for his dedication to his writing. "A good man will not learn the wiles of art": the sentiment recurs throughout the mature work.

"I was essentially a man of short-lived passions, visions and dreams, not fit material for a husband and father", Milosz mourns in the "Materials for My Biography" (undated) that Andrzej Franaszek uncovered among the poet's voluminous unpublished writings. Milosz's marriage to his brilliant, acerbic first wife, Janina Dluska, produced two sons and lasted fifty years, surviving the separations, infidelities and physical and mental illnesses that Franaszek describes in sympathetic, un-emphatic detail. The family's struggles, the isolation, the scant readership on both sides of the Atlantic: these troubles took Milosz and his life story in a distinctive direction in the 1970s.

For William Blake, "every true poet must spend his life making the Bible anew", Lawrence Lipking comments in The Life of the Poet (1981). Milosz outdid his beloved Blake by learning Hebrew and Greek in his sixties. He aspired to translate the Bible into Polish for the first time from the original tongues, not Latin (he managed only 700 pages). He tackled Job early on, and his translator’s preface shows how closely he linked the story to his own fate. Long suffering, his own and others', exile from his childhood home, moral failings, the price for prophecy, the century's hard history: "my imagination cannot make peace with Job's lament within me", he comments.

The volume of biblical translations in the Polish Collected Works suggests the limits of the Milosz who is so widely admired in the English-speaking world. The translations that intermingle with original work - though he would have resisted the distinction - in the Polish collections have vanished from their English-language counterparts. More than this: the metrical innovator, who absorbed and transmuted forms not just from the Polish, but the French and Anglo-American traditions with breathtaking facility, likewise largely goes missing. And this is chiefly Milosz's own doing. Unlike his friend and fellow émigré Joseph Brodsky, he refused to sacrifice sense for structure in translation, and generally left his most intricately structured work un-translated or translated it into free verse, as in The Treatise on Poetry. His exquisite version, with Robert Pinsky, of the "Song on Porcelain" (1947), gives hints of the poet who is Milosz at his best for many Polish readers.

The Nobel Prize not only brought him back to life in Poland; the government could no longer keep his work from finding its way into print. It also gave him the opportunity to rewrite the story of his life for the new audience the prize had brought him. And rewrite it he did. To give just one example: perhaps his best-known collection, the volume known in English as Rescue (Ocalenie, 1945), is just about half the length of its Polish counterpart.

The tale it tells of the evolving poet, who discovers too late the "salutary aim" of "good poetry" is thus oddly - strategically? - truncated in English. The great poet spends a lifetime rewriting and revising the great Book of his story in art, Lipking argues. "The past is never closed down and receives the meaning we give it by our subsequent acts", Milosz comments in a late poem. Few poets have had the chance to re-create their past in art in another language for a new public as Milosz did in his last decades. The disparities between the tales he tells in English and Polish are revealing in ways that remain to be explored.

The complexities of Milosz's Polish-Lithuanian past may elude most Anglophone readers. But his forty years in Californian exile remain equally opaque to his Polish audience. They received short shrift in the centennial events I attended in recent months. My defence of Milosz as, inter alia, an American and even a Californian poet took Polish specialists aback. "I thought his America was just [Henry] Miller's 'air-conditioned nightmare''', one scholar commented. But Milosz's - typically volatile - relationship with American culture far predates his first visit to the United States. "I was raised in large part on American literature", he recalls in A Perverse Self-Portrait. As a child, he loved his abridged, one-volume translation of James Fennimore Cooper's Leather stocking Tales: little Czeslaw played at Natty Bumppo in the Lithuanian woods. When the young poet discovered Walt Whitman some years later, his reaction was immediate: "Revelation: to be able to write as he did!".

His appetite for American literature and history continued unabated throughout his years in exile. Milosz was an inveterate researcher and often did his homework on the road: in one lovely footnote, Franaszek lists the various Volvos, Dodges, and Pontiacs the Milosz family wore out. The road trips, the reading and the "wondrously quick eyes" Milosz recalls in a late poem combine to make him an astute interpreter of the West's landscapes and hidden histories in his poetry and prose alike. As his friend, the poet Jane Hirshfield comments, "he loved California enough to argue with it".

"He would like to be one, but he is a self-contradictory multitude", Milosz writes in ''The Separate Notebooks" (1977-9). Pole, Lithuanian, Californian, poet, essayist, novelist, historian, metaphysician, translator, scholar, anti-confessional autobiographer, Job, Gump and Foolish Jack: how can they be reconciled? The short answer is: they can't. The poet of "Song of a Citizen" (1943) imagines his ideal bardic fate from wartime Warsaw: "In my later years, / Like old Goethe to stand before the face of the earth, / And recognize it and reconcile it / With my work built up, a forest citadel/on a river of shifting lights and brief shadows". The lights and shadows mingle throughout the life's work Milosz built up, in multiple languages and genres, over the course of his century. But his is no citadel. The work, like the life, is both overwhelming and endlessly approachable, since this master of self-contradiction resisted final systems even as he struggled to create them. "Why do I still have so many doubts at my age?", he asked in a late conversation. We are lucky to have had a doubter of such prodigious gifts in our midst.

Comments

Post a Comment