HEART OF DARKNESS

Ông là Đồ Phổ Nghĩa, tôi đoán vậy...

Đầu tháng Tám, 1890, con tầu Vua Người Bỉ bắt đầu chuyến ngược dòng Congo. Thuyền trưởng, Konrad Korzeniowski, gốc Ba-lan, mới tới Congo, một thuộc địa mà Leopold II, vua nước Bỉ vừa chiếm đoạt được, cho riêng mình, ngay tại giữa Phi-châu. Muốn tìm hiểu con sông, trong nhật ký của thuyền trưởng, là chi tiết tỉ mỉ chuyến đi, cả những gì không liên quan đến ngành hàng hải. Một tháng sau, khi chuyến đi chấm dứt, Conrad, bị sốt rét, thổ tả, và với một cõi lòng tan nát khi tận mắt chứng kiến sự tàn bạo của đám da trắng chung quanh, ông bỏ việc, trở lại Âu-châu.

Tới Phi châu, mục đích chính là để tìm kiếm một thế giới xa lạ (exotic), của những giấc mơ ấu thời; ông trở về với một giấc mơ mới: viết Giữa Lòng Đen, Heart of Darkness, điều được ông mô tả: cuộc tranh giành của cải xấu xa, ghê tởm nhất, làm méo xệch lịch sử lương tâm nhân loại (that ever disfigured the history of human conscience).

Giới nhà văn, học giả thường đọc Giữa Lòng Đen bằng những từ của Freud, Nietzsche. Cuốn tiểu thuyết còn nhắc nhở, về sự thơ ngây vô tội, thời Victoria, và tội tổ tông; hay chế độ gia trưởng tàn bạo và thời kỳ tôn giáo thần bí Gnosticism, chủ nghĩa hậu-hiện đại, hậu-thực dân, hậu-cơ cấu. Với trăm ngàn nghiên cứu, luận chứng cao học, tiến sĩ này nọ, người ta thật dễ dàng quên đi, rằng cuốn tiểu thuyết đã mang trong nó một cái gì thuộc về phóng sự, nói rõ hơn, đây là một giả tưởng dựa trên người thực, việc thực.

Trong cuốn tiểu thuyết, Marlow, người kể chuyện, một hóa thân (alter ego) của Conrad, được một công ty săn ngà voi mướn đi theo một con tầu, ngược dòng sông nhiệt đới, để gặp Mr. Kurtz, tay mại bản đầy tham vọng, và thật thông minh, sáng giá, đại diện công ty. Dọc đường, Marlow nghe xì xào, Kurtz đã thu gom được một mớ ngà voi kếch xù, và đã phạm vào một chuyện dã man không được xác định rõ (unspecified). Thoát chết sau một cuộc tấn công của thổ dân, đoàn của Marlow lấy được một chuyến hàng, luôn cả Kurtz, đang ngắc ngoải vì bịnh. Anh ta nói về những kế hoạch đồ sộ của mình, chết khi con tầu xuôi hạ lưu, nhưng sống mãi, trong cuốn tiểu thuyết của Conrad: một gã da trắng cô độc, lân la mãi tít thượng nguồn con sông lớn, với những giấc mơ hoành tráng, kho ngà voi, và một đế quốc phong kiến vượt lên trên những khu rừng rậm Phi-châu.

Độc giả khó thể quên, cảnh tượng Marlow, trên boong tầu, chiếu ống nhòm, tới những vật mà ông miêu tả là những đồ trang điểm, ở trên ngọn những con sào, gần nhà Kurtz, và rồi ông nhận ra, mỗi món đồ trang trí đó là một cái đầu lâu - đen, khô, mi mắt xụp xuống, cái đầu lâu như đang ngủ trên ngọn con sào. Những người chưa từng đọc cuốn truyện, cũng có thể nhìn thấy cảnh này, bởi vì nhà đạo diễn Francis Coppola đã mượn nó, khi chuyển Heart of Darkness vào trong phim Tận Thế Là Đây, Apocalypse Now. Những hình ảnh như thế đã khắc họa Kurtz, như một hình vóc văn hóa: thực dân, chinh phục. Mới đây thôi, trên trang nhất tờ Times đã mô tả một viên chỉ huy dã man, của lực lượng đánh thuê người Serbia, ở Zaire, như là một bạo chúa, ấn bản hiện đại của Kurtz trong Giữa Lòng Đen. Một Kurtz thời hiện đại khác, có tên là Đại tá Yugo, ngự trị bằng khủng bố tại thành phố Kisangani, với hàng loạt vụ sát nhân, xử tử, với những trò tra tấn thường nhân bằng roi điện, để mặc tù nhân chết đói. Kisangani, có tên là Stanley Falls, khi con tầu của Conrad tới nơi này, vào năm 1890, và được ông đặt tên là Trạm Nội, Inner Station, trong Heart of Darkness. Đây cũng chính là chỗ ngày trước Kurtz vung vãi những trò chơi khủng bố, giết thổ dân.

Chẳng nghi ngờ chi, Conrad còn lấy Kurtz ra, từ trong sâu thẳm con người của ông. Và đây là điều người đọc miễn cưỡng thông cảm khi tưởng tượng ra một người da trắng, tham vọng vô bờ, và viễn ảnh về chính mình, một đấng giáo chủ của văn minh, giữa những giống dân man rợ. Nhưng Conrad còn tạo nên nhân vật của ông, trong sáu tháng ở Congo, từ những người ông đã gặp, hoặc đã nghe nói về họ, lúc này lúc nọ, và sau đó.

Một trong những nguyên mẫu mà sau này nhiều người viết tiểu sử, cũng như giới phê bình, chỉ ra, đó là Georges Antoine Klein, một Đồ Phổ Nghĩa ở Phi châu (Jean Dupuis, tên Việt là Đồ Phổ Nghĩa, đã từng ngược sông Hồng, kiếm đường thông thương với Trung-hoa, thời Francis Garnier đánh chiếm Bắc-kỳ); ông Tây này, đại diện cho một công ty thu gom ngà voi ở Stanley Falls, bến tới của Conrad. Con tầu Roi des Belges đã nhặt Klein, khi ông ta bịnh, và sau đó, chết trên tầu, trong chuyến về. Ngoại trừ những chi tiết đó, và sự tương tự giữa hai tên (Kurtz/ Klein), Conrad không lấy ra được nhiều, từ nhân vật này. Có người lại cho thấy, nguyên mẫu của tác giả là một mại bản tên là Arthur Hodister, một người Bỉ nổi danh vì tài thu gom ngà voi. Vào năm 1892, hai năm sau khi Conrad rời Congo, tay này bị đối phương cùng nghề tóm được và chặt đầu. Về những cái đầu lâu đang ngủ trên ngọn sào, nhà phê bình Norman Sherry viết, chúng có lẽ là chuyển thể của số mệnh Hodister. Nhưng có đúng là chuyển thể, nói rõ hơn, Conrad đã hư cấu Kurtz, bằng tưởng tượng nhiều hơn là từ thực tế? Những nhà phê bình như Sherry đã cố tình lờ đi, vô số những nguyên mẫu khác: những người da trắng chuyên thu gom đầu lâu da đen.

Người đầu tiên, trong số họ, là Guillaume Van Kerckhoven, một tay phiêu lưu, vốn là sĩ quan Lực Lượng Công Cộng, Force Publique, một lực lượng da đen, do da trắng chỉ huy. Vào lúc Conrad viếng Congo, lực lượng này đang bận rộn với công việc khai hóa, giữa những sắc dân nổi loạn suốt vùng đất thuộc địa bao la của vua Bỉ, Leopold II. Van Kerckhoven nổi tiếng thu gom, vừa ngà voi vừa nô lệ da đen. Một trong những chuyến đi khai hóa của anh ta, đã được một vị toàn quyền mô tả: một trận bão quét qua trọn xứ sở, không để lại bất cứ một cái gì sau nó, nếu có chăng, chỉ là điêu tàn. Van Kerckhoven còn có thói quen, thưởng lính thổ dân dưói quyền, về mỗi cái đầu mang về, sau mỗi chuyến hành quân.

Ghi chú, tài liệu những ngày Conrad ở Congo không nhiều, chúng ta không biết tác giả có gặp nhân vật kể trên không, nhưng một tay du lịch đã nghe câu chuyện Van Kerckhoven chuyên thu gom đầu người, đó là Roger Casement, một trong những bạn tốt ở Phi châu của tác giả. Casement sau nổi tiếng vì tranh đấu cho nhân quyền, và là một nhà ái quốc Ái nhĩ lan; một trong số hiếm hoi, đen hay trắng, tác giả gặp ở Phi châu: một người suy nghĩ, giỏi ăn nói, rất thông minh, và rất có cảm tình, Conrad viết trong nhật ký về bạn. (Roger Casement 1864-1916, có thời kỳ làm cho Sở Hỏa Xa Congo. Ông sau bị người Anh treo cổ, vì hoạt động nhân quyền). Vài năm sau, cả hai chạy lại, ôm lấy nhau, trong một tiệm ăn Luân-đôn, rồi sau đó, kéo tới câu lạc bộ thể thao, Sports Club, nói chuyện cho tới 3 giờ sáng. Đó là trước khi Conrad viết Giữa Lòng Đen. Casement có tài ăn nói thật khác thường, và cái kho chuyện của ông chắc chắn đã ảnh hưởng Conrad, về viễn ảnh của một đại lục. "Anh ta có thể kể cho bạn những điều." Conrad viết thư cho một người bạn, về Casement. "Những điều mà bạn cố quên đi."

Khi bắt đầu viết Giữa Lòng Đen, chắc chắn trong đầu tác giả còn có một nguyên mẫu thứ nhì, chuyên thu gom đầu da đen Phi châu: Léon Rom, cũng sĩ quan Force Publique. Còn là một chuyên viên thu gom mề đay, do những thành tích chiến đấu, và có tên trong văn chương Bỉ, về thời đại anh hùng khai hóa. Năm 1895, một nhà thám hiểm người Anh, còn là một ký giả, ghé qua Stanley Falls, nơi Rom chỉ huy. Viên ký giả sau ghi lại, trên báo Thế Kỷ, Century, về một chuyến hành quân của Rom, tiễu trừ thổ dân nổi loạn chống chế độ thực dân, khai hóa: Đàn bà trẻ con đều bị tóm hết, hai muơi mốt đầu lâu được đem tới thác, và được Đại úy Rom dùng làm đồ trang trí quanh thảm hoa, trước nhà ông. Nhà văn Jules Marchal, người Bỉ, những cuốn sách của ông được dùng làm tài liệu sử về thời kỳ này, đã khui ra một chi tiết khác: tại thác Stanley Falls, Rom cho dựng một giá treo cổ, thường trực, ngay trước bộ chỉ huy của ông. Có thể Conrad bỏ qua tờ Century, nhưng ông là độc giả trung thành của Điểm báo thứ Bẩy, Saturday Review, London. Tờ này cũng nói tới Đại úy Rom và 21 đầu lâu ông thu gom, trong số báo Tháng Chạp 17, 1898. Có thể nguyên mẫu, và tiểu thuyết gia đã từng gặp nhau, tại Congo, vào ngày 2, tháng Tám, 1890, khi Conrad đi cùng một người da trắng khác, với một đoàn thổ dân khiêng đồ đạc, sau chuyến đi dài từ bờ biển tới điểm xuất phát chuyến vượt sông Congo. Trước khi tới làng Kinshasa ở ven sông, nơi con tầu Vua Người Bỉ đợi ông, Conrad đi qua đồn ven biên Leopoldville. Ở cả hai nơi lúc đó chỉ có chừng hai chục người da trắng, vài căn nhà rải rác. Những năm sau đó, hai đồn này bành trướng mãi ra rồi nhập vào nhau, và là thành phố Leopoldville dưới thời người Bỉ, và bây giờ là Kinshasa. Vào cái ngày mà Conrad đi qua Leopoldville, viên sếp đồn là Đại úy Léon Rom. Conrad nói tiếng Pháp gần như hoàn hảo, cả hai như vậy có chung một ngôn ngữ. Khi đọc Century, hay Saturday Review, có thể ông đã tưởng tượng ra được viên sĩ quan trẻ mà ông đã từng gặp.

Có rất nhiều tương tự đáng nói, giữa Rom và Kurtz. Nhưng Rom và Van Kerckhoven không chỉ là hai nguyên mẫu. Nhiều người khác nữa, cũng có cùng đam mê thu gom đầu lâu da đen. Những nhà phê bình đã cố tình quên chính tác giả Conrad, khi ông ngắm nghía đứa con tinh thần của mình, ngay trong Ghi chú của Tác giả, lần xuất bản 1917:... Heart of Darkness chỉ cố nhón lên cao hơn chút xíu, những sự kiện thực, chỉ một chút xíu thôi. (Heart of Darkness is experience pushed a little - and only very little - beyond the actual facts of the case).

Những người Âu châu, và người Mỹ thường ngần ngại, khi nhìn cuộc chinh phục Phi-châu, cũng một trò diệt chủng y hệt như Hitler, hay Stalin. Vì lý do đó, chúng ta đành phải chấp nhận, và "cảm thấy thoải mái", khi nghĩ rằng, chuyện thu gom đầu lâu chỉ là một chuyển thể ghê rợn, một giả tưởng do trí tưởng tượng của Conrad thêu dệt ra. Trong những chuyển thể như thế, có phim của Manuel Aragon, người Tây-ban-nha, được chuyển thể tại Tây-ban-nha sau cuộc nội chiến. Coppola lại chuyển câu chuyện tới Việt Nam. Chỉ có lần thứ ba, câu chuyện được đặt để tại Phi-châu, vào năm 1994, nhưng lại là phim cho cable TV.

Hãy thử tưởng tượng Một Ngày Trong Đời Ivan Denisovich, của Solzhenitsyn, được quay tại Liên-bang Xô-viết. Hay Đêm của Elie Wiesel, quay ngay tại Lò Thiêu Auschwitz.

******

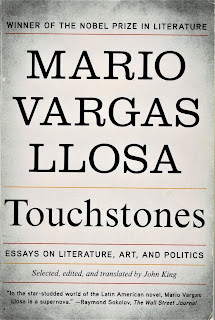

Vargas LLosa đọc Trái Tim Của Bóng Đen. Ông còn viết 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết về Casement - kể như bạn của Conrad, người cung cấp nguyên liệu để viết Heart of Darkness. Bài này, đầy đủ, chi tiết về tội ác của nhân loại ở xứ Congo thuộc Bỉ. Tội ác của Bắc Kít không thể so với nó, nhưng ở yếu tính, chúng như nhau. Bắc Kít chưa hề coi Nam Kít như là ruột thịt của chúng. Đó là sự thực.

NQT

Heart of Darkness

The Roots of Humankind

I. The Congo of Leopold II

On a plane journey, the historian Adam Hochschild found a quotation from Mark Twain in which the author of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn asserted that the regime imposed in the Free State of the Congo between 1885 and 1906 by Leopold II, the King of the Belgians who died in 19o9, had exterminated between five and eight million of the native inhabitants. Disconcerted, and with his curiosity aroused, he began an investigation that, many years later, would culminate in King Leopold's Ghost, an outstanding document on the cruelty and greed that drove the European colonial adventure in Africa. The information contained in the book and the conclusions that it reaches greatly enrich our reading of Joseph Conrad's masterpiece, Heart of Darkness, which was set in that country just at the time when the Belgian Company of Leopold II— who must rate alongside Hitler and Stalin as one of the bloodiest political criminals of the twentieth century — was perpetrating the worst of its insanities.

Leopold II was an obscenity of a human being; but he was also cultured, intelligent and creative. He planned his Congolese operation as a great economic and political enterprise designed to make him both a monarch and a very powerful businessman, with a fortune and an industrial and commercial network so vast that he would be in a position to influence political life and development in the rest of the world. His Central African colony, the Congo, which was the size of half of western Europe, was his personal property until 1906, when pressure from various governments, and from public opinion that had been alerted to his monstrous crimes, forced him to cede the territory to the Belgian state. It was also an astute public relations exercise. He invested considerable sums in bribing journalists, politicians, bureaucrats, military men, lobbyists and church officials across three continents to put in place a massive smokescreen that would make the world believe that his Congolese adventure had the humanitarian and Christian aim of saving the Congolese from the Arab slave traders who raided their villages. With his sponsorship, lectures and congresses were organised that attracted intellectuals — mercenaries without scruples, both naive and stupid — and many priests to discuss the most practical means of taking civilisation and the Gospels to the cannibals in Africa. For a number of years, this Goebbels-style propaganda was effective. Leopold II was decorated, praised by religious groups and the press, and was considered a redeemer of black Africans.

Behind this imposture the reality was different. Millions of Congolese were subjected to iniquitous exploitation in order to fulfil the quotas on rubber, ivory and resin extraction that the Company imposed on villages, families and individuals. The Company had a military organisation and abused the workers to such an extent that, comparison, the former Arab slave traders must have seemed like angels. They worked with no fixed hours and without payment, terrified at the constant threat of mutilation and death. The physical and mental punishments became sadistically refined: anyone not reaching their quota had a hand or a foot cut off. Dilatory villages were sacked and burned in punitive expeditions that kept the population cowed and thus curbed runaways and attempts at rebellion. To keep families completely submissive, the Company (it was just one company, hidden behind a dense thicket of different enterprises) kept in their custody either the mother or one of the children. As it had few overheads — it did not pay wages and its only real expense was arming uniformed bandits to keep order — its profits were fabulous. As he had set out to be, Leopold II became one of the richest men in the world.

Adam Hochschild calculates, persuasively, that the Congolese population was reduced by half in the twenty-one years that the outrages of Leopold II continued. When the Free State of the Congo passed to the Belgian state in 1906, even though many crimes were still being committed and the merciless exploitation of the native population was maintained, conditions did improve quite considerably. Had that system continued, it is in the realms of possibility that these people might have been completely wiped out.

Hochschild's study demonstrates that, while the crimes and tortures inflicted on the native population were grotesquely horrendous, the greatest damage done to them was the destruction of their institutions, their kinship systems, their customs and their most fundamental dignity. It is not surprising that when, some sixty years later, Belgium gave independence to the Congo in 1960, the ex-colony, in which no local professional infrastructure had been created by the colonising power in almost a century of exploitation, plunged into chaos and civil war. And finally, it fell into the hands of General Mobutu, an insane satrap, a worthy successor of Leopold II in his voracity for wealth.

There are not only criminals and victims in King Leopold's Ghost. There are also, fortunately for humankind, people who offer some redemption, like the black American pastors George Washington Williams and William Sheppard who, when they discovered the true nature of the farcical regime, took immediate steps to denounce to the world the terrible reality of Central Africa. But the two people who, showing extraordinary bravery and perseverance, were mainly responsible for mobilising international public opinion against Leopold II's butchery in the Congo, were an Irishman, Roger Casement, and a Belgian, Morel. Both deserve the honours of a great novel. The former (who in later years would first be knighted and later executed in Great Britain for participating in a rebellion for the independence of Ireland) was, for a period, the British vice-consul in the Congo. He inundated the Foreign Office with lapidary reports on what was happening there. At the same time, in the customs house in Antwerp, an enquiring and fair-minded official, Morel, began studying, with increasing suspicion, the shipments that were leaving for the Congo and those that were returning from there. What a strange trade it was. What was sent to the Congo was in the main rifles, munitions, whips, machetes and trinkets of no commercial value. From there, by contrast, came valuable cargoes of rubber, ivory and resin. Could one take seriously the propaganda that, thanks to Leopold II, a free trade zone had been created in the heart of Africa that would bring progress and freedom to all Africans?

Morel was not only a fair-minded and perceptive man. He was also an extraordinary communicator. When he discovered the sinister truth, he made it known to his compatriots, skilfully circumventing the barriers erected to keep out the truth of what was happening in the Congo, which were kept in place by intimidation, bribes and censorship. His analyses and articles on the exploitation suffered by the Congolese, and the resulting social and economic depredation, gradually gained an audience and helped to form an association that Hochschild considers to be the first important movement for human rights in the twentieth century. Thanks to the Association for the Reform of the Congo that Morel and Casement founded, Leopold was no longer seen as some mythic civilising force, but rather in his true colours as a genocidal leader. However, by one of those mysteries that should be deciphered one day, what every reasonably well-informed person knew about Leopold II and his grim Congolese adventure when he died in 1909 has now disappeared from public memory. Now no one remembers him as he really was. In his own country he has become an anodyne, inoffensive mummy, who appears in history books, has a number of statues and his own museum, but there is nothing to remind us that he alone caused more suffering in Africa than all the natural tragedies and the wars and revolutions of that unfortunate continent.

II. Konrad Korzeniowski in the Congo

In 1890, the merchant captain Konrad Korzeniowski, Polish by birth and a British national since 1888, could not find a post senior enough for his qualifications in England, and signed a contract in Brussels with one of the branches of the Company of Leopold II, the Societe Anonyme Belge that traded in the upper Congo, to serve as a captain on one of the company’s steamboats which navigated the great

[còn tiếp]

THE LASTING POWER OF "HEART OF DARKNESS"

Joseph Conrad's slim novel may be the single most influential hundred pages of the 20th century, writes Robert Butler in his latest Going Green column ...

From INTELLIGENT LIFE Magazine, Winter 2010

It was a beautiful moment in 1887 when a veterinary surgeon in Northern Ireland invented a new kind of tyre, to smooth out the bumps when his son was on his tricycle. Within ten years John Dunlop’s pneumatic tyre—inflated canvas tubes, bonded with liquid rubber—had become so successful that the American civil-rights leader Susan B. Anthony could claim, “The bicycle has done more for the emancipation of women than anything else in the world.”

The invention didn’t free everyone. The raw material for the pneumatic tubes came from the rubber vines of the Congo, and the demand for rubber only deepened the damage that had been inflicted in that region by the demand for ivory. A century later, the pattern hadn’t entirely changed: the coltan required for mobile phones comes from the same area, where war has claimed millions of lives over the past 12 years.

Our awareness of the shadowy stories of supply and demand also goes back to one man, a contemporary of Dunlop’s. Between June and December 1890, a 32-year-old unmarried Polish sailor called Konrad Korzeniowski made a 1,000-mile trip up the Congo for an ivory-trading company on a paddleboat steamer called Roi des Belges. It took him nine years to find a way to write about what he saw. Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” is a story within a story, which starts with five men on a boat moored in the Thames, and one of them, Marlow, a veteran seaman and wanderer, telling of a journey up a serpentine river into the centre of Africa, where he meets another ivory trader, Kurtz. Six pages in, Marlow tells the others, “The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.”

Published in 1902, “Heart of Darkness” had an immediate political impact—it was widely cited by the Congo Reform Movement—but it wasn’t an instant classic. Twenty years later, T.S. Eliot wanted to choose a quotation from it for “The Waste Land”, but his colleague Ezra Pound dissuaded him: “I doubt if Conrad is weighty enough to stand the citation.” Three years after that, Eliot chose another line from the novella as one of the epigraphs for “The Hollow Men”. (“Mistah Kurtz—he dead.”) “Heart of Darkness” had become part of the cultural landscape. In 1938 Orson Welles adapted it for a Mercury Theatre live radio production. He went on to write a screenplay in which he planned—with Wellesian gusto—to play both Marlow and Kurtz. He couldn’t get the movie made and was forced to move on to a project about a media mogul called Charles Foster Kane.

In the late 1970s, Francis Ford Coppola took “Heart of Darkness” and transplanted it to Vietnam as “Apocalypse Now”, with Martin Sheen as Captain Willard, the Marlow character, a special-operations officer, sent on a mission to “terminate…with extreme prejudice” the life of the deranged Captain Kurtz, played by Marlon Brando. In this version the Mekong River becomes the Congo. The irony was hard to miss: just as Britain, once colonised by the Romans (“1,900 years ago—the other day”, writes Conrad), had become an imperial power, so had the United States, once colonised by the British, now become one too. With the success of the movie, the novella’s place on the campus syllabus was assured. “Apocalypse Now” launched a thousand sophomore essays comparing and contrasting the book and the movie.

And now “Heart of Darkness” is a graphic novel by Catherine Anyango, with the ivory domino pieces—lightly touched on by Conrad in the opening pages—looming in the foreground of the opening drawings. The theme of traceability, where things come from and the journey that they take, is vividly dramatised. It’s a story for today. One day in June last year, Jeff Swartz, CEO of the leisurewear company Timberland, woke up to find the first of 65,000 angry e-mails in his inbox. These were responses to a Greenpeace campaign that said Brazilian cattle farmers were clear-cutting forests for cattle and the leather from the cattle was going into Timberland shoes. Swartz has written up his experience for the Harvard Business Review. His first action, he says, was to admit that he didn’t know where the leather came from. It wasn’t a question he had asked.

As “Heart of Darkness” has moved from one medium to another, it has made a good claim to be the single most influential hundred pages of the 20th century. If you consider its central theme—how one half of the world consumes resources at the expense of the other half—it’s easy to see its relevance becoming even greater. Only the resources will no longer be ivory for piano keys, or rubber for bicycle tyres.

Conrad’s artistic challenge was to make the world he saw visible to others. It’s a political challenge too. Sometimes writers reveal a hidden situation, sometimes campaigners do, and sometimes it’s just an accident. Few of us had much idea about the conditions in which copper is mined—everyday copper for plumbing, electrics, saucepans and coins—before 33 Chilean miners found themselves trapped 2,000 feet underground.

Robert Butler is a former theatre critic. He blogs on the arts and the environment at the Ashden Directory, which he edits. Picture Credit: Gastev (via Flickr).

Ideas GOING GREEN Intelligence winter 2010

*

how one half of the world consumes resources at the expense of the other half:

Câu trên chôm và áp dụng vào xứ Mít, được: Bằng cách nào anh Yankee mũi tẹt, tức nửa nước Mít phía Bắc, 'tiêu thụ', thằng em Nam Bộ, tức nửa nước Mít phía Nam.

Đọc bài điểm sách trên, thì ngộ ra 1 điều, lịch sử nhân loại, và cùng với nó, là lịch sử văn học thế giới, hoá ra chỉ qui về… hai cuốn truyện: "Trái Tim của Bóng Đen"

, một nửa thế giới tiêu thụ tài nguyên của 1 nửa thế giới còn lại; Bóng Đêm giữa Ban Ngày, 1 nửa nhân loại và sau đó, toàn thể nhân loại, thoát họa Quỉ Đỏ.

Khi viết Bếp Lửa, TTT không hề nghĩ rằng, cuốn sách của ông là cũng nằm trong truyền thống trên.

Bởi vì nó cũng thuật câu chuyện một nửa nước Mít làm thịt một nửa nước Mít.

“The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.”

Published in 1902, “Heart of Darkness” had an immediate political impact…

Cuộc chinh phục Miền Nam, nghĩa là cuộc làm thịt đám Ngụy, thì không bị được đẹp cho lắm, nếu nhìn thật gần, và nhìn thật ‘nâu’ [‘lâu’, đọc giọng Bắc ], và thật nhiều…

Xb vào năm 1954, BL lập tức trở thành một cú chính trị ‘đéo phải đạo’ [dám gọi cái chuyện đi lên chiến khu, vô rừng, theo Chiến Kháng, "cũng là 1 thứ đánh đĩ"!]….

Viết, Tháng Tư

Heart of Darkness

Ầm ầm sóng vỗ chung quanh ghế ngồi

Câu thơ trên, của Nguyễn Du, trong truyện Kiều, tả cảnh Kiều ở trung tâm một trận bão, lụt, làm Gấu nhớ tới cái truyện ngắn chỉ có được mỗi cái tên truyện của Gấu: Mắt Bão.

Nhớ, cả cái bữa ngồi Quán Chùa, khoe cái tít với ông anh, ông biểu, còn nhiều từ như thế lắm, ở trong môn học địa lý.

Nhưng, "ầm ầm sóng vỗ chung quanh ghế ngồi", còn là cái dáng ngồi như ông Bụt của Marlow, khi anh kể lại câu chuyện của Kurtz, trong Trái Tim Của Bóng Đen.

Và đúng là cái tâm trạng của NHT, kẻ "chẳng bao giờ đi xa và cứ ở mãi đây", ở cái xứ Bắc Kít. Ở trung tâm của Bóng Đen.

Ở Mắt Bão.

Bien qu'il n'ait jamais disparu, le courant brun qui coulait rapidement du cœur des ténèbres vers la mer en nous emportant sur le fleuve Congo est de retour. Et avec lui revient le personnage de Kurtz qui, lui non plus, n'a jamais disparu, ou s'il l'a fait, il était « parti très loin, comme dirait Kafka, pour rester ici ».

Thì, tất nhiên, nó chẳng bao giờ biến mất, cái dòng nước đục ngầu, đỏ như máu, của sông Hồng, chảy từ trái tim của bóng đen, là thành phố Hà Nội, ra biển, đưa chúng ta dạt dào lưu vong, sau khi thoát hải tặc Thái lan, mãi tít tới miệt Công Gô, và, ăn Tết Công Gô xong, lại trở về.

Và cùng về với nó, là nhân vật Kurtz; anh này, tất nhiên, cũng chẳng hề biến mất, hay là, nếu anh ta làm như thế, “anh ta đi rất xa, nói như Kafka, để ở lại đây”.

Kurtz, như thế, họ hàng với Colonel Sutpen, trong Absalom, Absalom!

Cũng dòng Yankee mũi tẹt, gốc gác Hải Dương [cùng quê PXA], hay Sơn Tây [cùng quê Tướng Râu Kẽm]?

Gấu bảnh hơn cả PXA & Râu Kẽm: Sinh Hải Dương, nhưng gốc dân Sơn Tây!

Gấu về Bắc lần đầu, năm 2000, là để tìm hỏi coi ông bố mình mất ngày nào, và đến chỗ ông mất, trên, ngày xưa chỉ là một bãi sông, thắp nén hương cho bố, rồi đi.

Mấy ông bạn văn VC nói, đi làm cái quái gì nữa, anh mua cái nhà, khu Thanh Xuân chẳng hạn, vừa gần Tướng Về Hưu vừa gần tụi này!

Đi rất xa, chỉ để ở lại đây!

Tôi nhớ xứ Đoài mây trắng lắm!

*

NHT cũng một thứ Kurtz, nhưng chẳng bao giờ rời xứ Bắc Kít!

Bảnh nhất trong những Trái Tim của Bóng Đen!

Ông Trùm.

Chẳng cần đi rất xa, và cứ ở mãi đây!

carnets de lecture

par Enrique Vila-Matas

KURTZ DES TÉNÈBRES

réédition d'Au cœur des ténèbres de Joseph Conrad

Bien qu'il n'ait jamais disparu, le courant brun qui coulait rapidement du cœur des ténèbres vers la mer en nous emportant sur le fleuve Congo est de retour. Et avec lui revient le personnage de Kurtz qui, lui non plus, n'a jamais disparu, ou s'il l'a fait, il était « parti très loin, comme dirait Kafka, pour rester ici ». Coïncidant avec le cent cinquantième anniversaire de la naissance de Joseph Conrad, paraissent en Europe diverses rééditions d'Au cœur des ténèbres.

Pourquoi ce roman est-il devenu un classique indiscutable et non Lord Jim, par exemple, qui est pourrtant, lui aussi, exceptionnel? Bien qu'il y ait des théories pour tous les goûts, j'ose croire que c'est moins à cause de l'influence d'Apocalypse Now ou de l'indubitable actualité de ses dénonciations du colonialisme que parce que Conrad y conçut un type de modèle narratif qui se répandit dans la littérature contemporaine.

La première partie d'Au cœur des ténèbres crée des expectatives à propos de l'énigmatique personnnage de Kurtz à la rencontre de qui le lecteur part en voyage. Mais le narrateur la repousse. C'est un livre dans lequel, en fait, à la différence de tant de romans de son époque, il ne se passe à peu près rien, même si le lecteur est de plus en plus avide de connaître Kurtz. Quand celui-ci finit par apparaître, le roman entame sa dernière ligne droite. On avait un immense désir de savoir comment est Kurtz, ce qu'il pense du monde et on entend un personnage si attendu dire simplement: « Je suis là couché dans le noir à attendre la mort (1). » Il annonce certains personnages de Beckett et de Kafka. Lorsque enfin on le voit, on découvre qu'on est arrivé jusque-là pour, en fait, tomber sur un homme brisé, affrontant les ténèbres qui enveloppent son propre être, incapable de ne dire que ces mots au sujet de la vérité ultime de notre monde: « Horreur! Horreur! »

Aujourd'hui, Kurtz est encore ici, au fond de notre forêt intérieure indisciplinée et de la nuit de nos ténèbres. Et nous sommes toujours en lui. Bertrand Russell fut le premier à prévoir que ce grand récit de Conrad résisterait énergiquement au temps. Pour Russell, c'est celui dans lequel est le mieux traduite la vision du monde de son grand ami Conrad, un écrivain qui s'imposait une forte discipline intérieure et qui considérait la vie civilisée comme une dangereuse promenade sur une mince couche de lave à peine refroidie qui, à tout instant, peut se briser et englouutir l'imprudent dans un abîme de feu. Cette conscience des diverses formes de démence passionnée à laquelle les hommmes sont enclins était ce qui pousssait Conrad à croire aussi profondément à l'importance de la discipline.

Et j'en parle en connaissance de cause: je passe actuellement beaucoup de temps à étudier les divers sens pris par le mot « discipline » chez des personnes proches ou éloignées qui m'intéressent. En ce qui concerne Conrad, je peux dire que, sur ce chapitre, il n'était pas précisément moderne parce que - comme l'a déjà très bien expliqué Alberto Manguel - il n'estimait pas qu'il fallait rejeter la discipline comme dépourvue de nécessité (Rousseau et ses épigones progresssistes) ni la concevoir comme imposée avant tout de l'extérieur (autoritarisme) .

Joseph Conrad adhérait à la tradition la plus ancienne, selon laquelle la discipline doit venir de l'intérieur, puisqu'il s'agit d'une force mentale émise par notre propre génie du lieu, le genius loci, autrement dit nous-mêmes. L'homme ne se libère pas en donnant libre cours à ses impulsions et en se montrant changeant et incaapable de se contrôler, mais en soumettant la force de sa nature à un projet prédominant, à un code mental d'acier qui sache éliminer sa liberté la plus sauvage et le situer dans le cadre d'une vie disciplinée, en faisant appel aux desseins intérieurs du génie du lieu •

Traduit de l'espagnol par André Gabastou

(1) Au cœur des ténèbres, Joseph Conrad.

Traduit par Jean-Jacques Mayoux. GF-Flammarion, 1989. Signalons également la parution de textes partiellement inédits en français de Joseph Conrad, Du goût des voyages suivi de Carnets du Congo, trad. Claudine Lesage, éd. des Équateurs, 124 p., 12 €.

The 100 best novels: No 32 – Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899)

Joseph Conrad's masterpiece about a life-changing journey in search of Mr Kurtz has the simplicity of great myth

So far, on this list, with the possible exception of Alice in Wonderland (No 18 in this series), Heart of Darkness is probably the title that has aroused, and continues to arouse, most literary critical debate, not to say polemic. This is partly because the story it tells has the visceral simplicity of great myth, and also because the book takes its narrator (Charles Marlow), and the reader, on a journey into the heart of Africa.

Our encounter with Marlow's life-changing journey begins on the Thames in London, the great imperial capital, with his recollection of "the uttermost ends of the Earth". With brilliant economy, Conrad transports him to Congo on a quest that the writer himself undertook as a young man. There, working for the shadowy, but all-powerful "Company", Marlow hears of Mr Kurtz, who is described as a first-class Company servant. Once in the dark continent, Marlow is sent upriver to make contact with Kurtz, who is said to be very ill, and also to safeguard the security of the Inner Station. What he finds, after a gruelling journey to the interior, is a fellow European, who may or may not have gone mad, and who is worshipped as a god by the natives of the primitive interior. Kurtz, however, has paid a terrible price for his mastery. When Marlow finds him on his deathbed, he utters the famous and enigmatic last words: "The horror! The horror!"

Conrad's first and second languages were Polish and French, with his third language, English, not acquired until he was 20. English, however, was the medium he adopted to explore his youthful experience as a riverboat captain in Belgian Congo. Part of the work's strange hallucinatory atmosphere comes from the writer's struggle with a language that was not his mother tongue. He sometimes said he would have preferred to be a French novelist, and that English was a language without "clean edges". He once complained that "all English words are instruments for exciting blurred emotions". This, paradoxically, is perhaps what gives the book its famously enigmatic, and ambiguous, atmosphere.

Conrad finished writing Heart of Darkness on 9 February 1899. It was originally published as a three-part serialisation in Blackwood's Magazine from February to April 1899 (a commission for the 1,000th issue of the magazine), where it was promoted as a nautical tale by a writer whose work was at first (mistakenly) associated with the sea.

Heart of Darkness comes down to us in three other primary texts: a manuscript, a typescript and the final, revised version published in 1902. Not exactly a long story, and certainly not a novella, at barely 38,000 words long, it first appeared in volume form as part of a collection of stories that included Youth: A Narrative and The End of the Tether. It has become Conrad's most famous, controversial and influential work. The English and American writers who fell under its spell include TS Eliot (The Waste Land), Graham Greene (A Burnt-out Case), George Orwell (Nineteen-Eighty-Four) and William Golding (The Inheritors). It also inspired the Francis Ford Coppola 1979 film Apocalypse Now, a work of homage that continues to renew the contemporary fascination with the text.

None of Conrad's other books have inspired such veneration, especially in America, though some (including me) might want to place Nostromo (1904) higher up the pantheon. Critics have endlessly debated it. Chinua Achebe denounced it, in a famous 1975 lecture, as the work of "a bloody racist". Among the novels in this series, few novels occupy such an unassailable place on the list. It is a haunting, hypnotic masterpiece by a great writer who towers over the literature of the 20th century.

******

Books & arts

Jul 7th 2012 edition

Latin American fiction

A tragic hero’s tale

The Dream of the Celt. By Mario Vargas Llosa. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 404 pages; $27. Faber and Faber; £18.99.

IN 1884 Roger Casement, an ascetic young Ulsterman, joined an expedition up the Congo river led by Henry Morton Stanley, believing that commerce, Christianity and colonialism would emancipate the dark continent. When he left Africa 20 years later, Casement was the leading figure in an international campaign to denounce the abuses committed by the Congo's Belgian colonisers. As British consul, he published a report that detailed how the African population were beaten and mutilated to force them to supply rubber for export to Europe.

When news reached London that the rubber boom had prompted a similar reign of terror against the indigenous population in Putumayo, in the Peruvian Amazon, the British foreign secretary sent Casement to investigate with the words: “You're a specialist in atrocities. You can't say no.” His findings prompted the collapse of the Peruvian Amazon Company, the London-registered firm responsible. Casement was knighted, and the Times hailed him as “a great humanitarian”.

A passionate man of complex character, Casement is a tailor-made protagonist for Mario Vargas Llosa, a Peruvian writer who won the Nobel prize in literature in 2010. “The Dream of the Celt” is a meticulously researched fictional biography and a clever psychological novel.

Casement's fame quickly turned to notoriety. Only a few years after his lauded success in Peru he was hanged in London's Pentonville prison as a traitor. Having transferred his thirst for justice to the fight for Irish independence, he sought German military support for the cause during the first world war. Casement was caught in 1916 on an Irish beach during a foiled attempt to land 20,000 German rifles. His British captors sought to besmirch further his name by circulating diaries in which he detailed homosexual encounters with young men on several continents.

The strongest passages in the book are those in which the author skilfully interweaves scenes in Pentonville prison with details of Casement's earlier life to trace the evolution of Casement's consciousness. “The Dream of the Celt” is a moral tale. It is about the choice between denial or denunciation in the face of evil, and the fine line between activism and fanaticism. That makes an old story strikingly contemporary.

Comments

Post a Comment