Ted Hughes (1930-1998) and Sylvia Plath (1932-1963) are famous as tragic lovers as well as poets, and for many Plath is a feminist martyr.

Hughes was born in a small rural community in the Calder valley in Yorkshire. His parents ran a newspaper and tobacconists shop. His elder brother was a gamekeeper and used to take him up on the moors shooting, where Hughes fell in love with the wild.

Returning to the valley was, he recalled, like 'a descent into the pit . . . This was when the division of body and soul for me began.' The idea of animal life as truer and more real than human, and the association of animal life with killing and masculinity, are constants in his poetry. His father had served in the First World War and was one of only seventeen men from an entire regiment to return from

the doomed Gallipoli campaign. This, too, filled young Hughes's imagination with images of bloodshed.

From grammar school he won a place at Pembroke College, Cambridge, to read English Literature. But he felt that academic study betrayed his poetic self. He had a dream in which a creature with a fox's head came into his room, put bloody pawmarks on an unfinished essay he had written, and said, 'You are killing us.' So in his third year he changed from English to Anthropology — the beginning of his lifelong interest in magic and shamanism. He graduated in 1954, and on 25 February 1956 met Sylvia Plath at a party when, famously, she bit his cheek, drawing blood. They married four months later.

Plath was brilliant and rightly ambitious, though unstable. Both her parents were first-generation German immigrants living in a suburb of Boston, Massachusetts. Her father Otto was a university professor, specializing in bumblebees. Plath's later interest in beekeeping, and her linking of her father with Nazi Germany in the poem 'Daddy', derive from this family history (though Otto had left Germany at sixteen, before the Nazi era, and was a pacifist).

When Plath was four her father's health deteriorated. Fearing he had cancer, he refused to see a doctor. Actually he had diabetes and could have been saved. But he stubbed his toe, gangrene set in, his leg was amputated (hence Plath's reference to his single 'black shoe' in 'Daddy') and he died when Plath was eight. She told her mother 'I'll never speak to God again', and in her "Journals" she seems to blame her father for dying and deserting her.

She won a place at prestigious Smith College, where she worked hard to get A grades. A high-flier, she could not, she admitted, stand the idea of being mediocre, and she was conscious, too, of the need to feel physically desirable. With other top achievers she gained a brief internship on "Mademoiselle" magazine in New York, but found it unnerving. In August 1953 she attempted suicide, taking her mother's sleeping pills and locking herself in a cellar.

She was rescued by chance and received psychiatric treatment at McLean hospital, Massachusetts, later recalled in her acclaimed novel "The Bell Jar". Recovering, she won a Fulbright scholarship to Newnham College, Cambridge, which is how she came to meet Hughes.

Her "Journals" record her reaction to their first meeting: 'Oh, he is here, my black marauder, oh, hungry, hungry.' To her mother she wrote: 'I have fallen terribly in love which can only lead to great hurt. I met the strongest man in the world . . . a large, hulking, healthy Adam. . . with a voice like the thunder of God: At first they were supremely happy. When her Cambridge course finished they

sailed to New York on the "Queen Elizabeth" and she taught for a year at her old college, Smith. In the summer of 1959 they travelled across Canada and the United States, sometimes camping out in the wild. Their first child, Frieda, was born in April 1960.

By that time they were back in England, living in a flat near London's Primrose Hill, and a second child, Nicholas, was born in January 1962. Deciding to move to the country, they bought an old thatched house in Devon, and let the London flat to a Canadian poet, David Wevill, and his beautiful wife, Assia. Within months

Hughes had fallen passionately in love with Assia and walked out of his marriage to Plath. Distraught, she committed suicide in February 1963 by putting her head in a gas oven. Six years later Assia, whom Hughes refused to marry, killed herself and her daughter by Hughes, Shura.

Plath's belief in Hughes as a great poet never wavered, even after his betrayal, and she had worked hard while they were together to promote his career, taking on secretarial work to help pay for his keep and sending his poems to magazines and publishers. Her efforts paid off when he won a big poetry prize she had entered him for (the judges were Auden, Spender and Marianne Moore).

That led to the publication of his first collection, "The Hawk in the Rain", in 1957.

The poems in it, such as 'Wind' and 'Egg-head', take up a persistent Hughes theme - the fragility and misplaced pride of the human intellect that tries to shut out the anarchic, man-slaughtering world of nature. Another kind of violence, his father's war experiences, gets into 'Griefs for Dead Soldiers'. Hughes is interested in violence because (like the Pennine moors he went up to with his brother) it opens the way to an elemental, non-human level where primal energies flow and drive. Any form of violence: he wrote, 'any form of vehement activity invokes the bigger energy, the elemental power circuit of the universe.'

This theme continues in his second collection, "Lupercal" (1960). Plath's favourite poem in it was 'Fire-Eater', which seems baffling at first reading. Why are the stars 'the fleshed forebears' of the hills, and of Hughes's blood? Why is the death of a gnat 'a star's mouth'? Hughes had a keen interest in modern science and what he is referring to is the theory, then new, that the atoms in our bodies, excluding only the primordial hydrogen atoms, were originally fashioned in stars that formed, grew old and exploded countless aeons ago, scattering the elements as a fine dust through space, and allowing planets like the earth to form. So the earth and our bodies are made of star-dust, which is why the stars are 'forebears' of the hills and of Hughes's blood. According to the same theory, the universe is constantly recycling matter and energy, re-grouping molecules, so what feeds the universe is the death of anything in it. Even a gnat's death feeds the stars.

When Hughes looks at nature he sees relentless predators — the hawk in 'Hawk Roosting' (`My manners are tearing off heads'); the thrushes in 'Thrushes' (Nothing but bounce and stab'); the pike in 'Pike' Millers from the egg'). His pliant use of language is Shakespearean, inventing new words, making nouns into verbs. The thrushes are 'attent', a punchier word than 'attentive'; the pike's colour is variegated, 'green tigering the gold' — where the noun 'tiger' becomes a verb. Hughes's aim is to reinvigorate language. 'Words', he warned, 'are continually trying to displace our experience. And in so far as they are stronger than the raw life of our experience, and full of themselves, and all the dictionaries they have digested, they do replace it: But not if he can help it.

In the two months after Plath's death he wrote 'The Howling of Wolves' and 'Song of a Rat'. Both were published in "Wodwo" (1967) and both, as if in self-excuse, are about the inescapable cruelty and pain throughout the whole of nature. Then there was a gap. He started writing again in 1966, and "Crow", subtitled " "From the Life and Songs of the Crow", appeared in 1970 (dedicated 'In Memory of Assia and Shura'). Hughes considered it his masterpiece and many critics agree. Others shrank from its violence and negativity. The Crow of the title cannot be equated with any single concept. He changes from poem to poem — sometimes victim, sometimes tyrant, sometimes hero, sometimes fool. He is mythic in stature, but he demolishes myths — Christianity, humanism, the Genesis creation story and all hopeful and positive takes on life — reducing them to farce and slapstick. "Crow"'s anarchic refusal to conform to any existing stereotype was deliberate. 'My main concern', Hughes wrote, 'was to produce something with the minimum cultural accretions of the museum sort.'

Paradoxically, the inventiveness of "Crow" can be matched, in Hughes's later work, only by his translations from Ovid's "Metamorphoses". Titled "Tales from Ovid" (1997), they are not remotely like conventional translations. Hughes freely adds new passages to the original, and charges Ovid's passionate, disturbing stories with a sensuousness that makes them unmistakably his own.

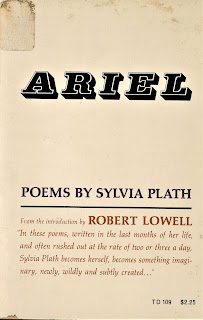

Plath published only one volume of poetry, "The Colossus" (1960), before her death. Her voice in it is often daring and sardonic, as it is in her later work. But the "Colossus" poems are less original, imitating Dylan Thomas, Yeats, Marianne Moore and Roethke. She owes her lasting fame to the poems she wrote in the months after Hughes had left her, which were published by him in 1965, titled "Ariel".

Her letters to her mother tell how she is writing 'the best poems of my life', at the rate of a poem a day, getting up at 4.00 in the morning while it is still dark (like writing in a train tunnel or God's intestine'), and breaking off only when the children wake.

The winter of 1962-3 was one of the coldest on record, and the cold is felt in the poems (for example, 'Nick and the Candlestick' with its 'panes of ice', or the bee-poem Wintering'). In Devon she had joined the village beekeepers, but the poems are about her rage and resentment, not beekeeping. The 'terrible' queen bee in 'Stings', with her lion-red body', is a female avenger, like the speaker in 'Lady Lazarus':

Comments

Post a Comment