THE OLD POET'S VOICE

Blindness privileged poetry. Now, it was easier for Borges to compose a poem in his head than a story or an essay. The predictable rhythms and even the rhymes, the musical structure of verse,

favored the memorizing and rewriting of it. Because he was virtually blind, Borges could go on endlessly composing his poems.

But the man who returned to poetry in his mid-fifties was a completely different craftsman. His young ambition of being able to write “the” poem had been forgotten. Now he favored

a more conventional, almost classical diction. In returning to the old craft, he wrote about some of the subjects he had already explored in fiction and essays, but the tone was more relaxed or casual, the revelations more

explicit. Tension had almost disappeared, self-irony had been toned down. Little by little, out of the ruins of the writer, the old bard emerged. His likes and dislikes, his foibles and manias, were all still there, but the

mood was softer. The older Borges assumed the mask of the blind poet.

THE GOLEM (I)

[JLB 83]

In a book inspired by infinite wisdom, nothing can be left to chance, not even the number of words it contains or the order of the letters; this is what the Cabalists thought, and they devoted

themselves to the task of counting, combining, and permutating the letters of the Scriptures, fired by a desire to penetrate the secrets of God. Dante stated that every passage of the Bible has a fourfold meaning—the

literal, the allegorical, the moral, and the spiritual. Johannes Scotus Erigena, closer to the concept of divinity, had already said that the meanings of the Scriptures are infinite, like the hues in a peacock's tail.

The Cabalists would have approved this view; one of the secrets they sought in the Bible was how to create living beings. It was said of demons that they could make large and bulky creatures like the camel but were incapable

of creating anything delicate or frail, and Rabbi Eliezer denied them the ability to produce anything smaller than a barley grain. Golem was the name given to the man created by combinations of letters; the word means, literally,

a shapeless or lifeless clod.

In the Talmud (Sanhedrin, 65b) we read:

If the righteous wished to create a world, they could do so. By trying different combinations of the letters of the ineffable names of God, Raba succeeded in creating

a man, whom he sent to Rabbi Zera. Rabbi Zera spoke to him, but as he got no answer, he said: "You are a magic; go back to your dust."

Rabbi Hanina and Rabbi Oshaia, two scholars, spent every Sabbath eve studying the Book of Creation, by means of which they brought into being a three-year-old calf

that they then used for the purposes of supper.

Schopenhauer, in his book Will in Nature, writes (Chapter 7): "On page 325 of the first volume of his Zauberbibliothek [Magic Library], Horst summarizes the teachings of

the English mystic Jane Lead in this way: Whoever possesses magical powers can, at will, master and change the mineral, vegetable, and animal kingdoms; consequently, a few magicians, working in agreement, could make this

world of ours return to the state of Paradise."

The Golem's fame in the West is owed to the work of the Austrian writer Gustav Meyrink, who in the fifth chapter of his dream novel Der Golem (1915) writes:

It is said that the origin of the story goes back to the seventeenth century.

According to lost formulas of the Kabbalah, a rabbi [Judah Loew ben Bezabel] made an artificial man—the aforesaid Golem—so that he would ring the bells and take over all

the menial tasks of the synagogue.

He was not a man exactly, and had only a sort of dim, half-conscious, vegetative existence. By the power of a magic tablet which was placed under his tongue and which attracted the free

sidereal energies of the universe, this existence lasted during the daylight hours.

One night before evening prayer, the rabbi forgot to take the tablet out of the Golem's mouth, and the creature fell into a frenzy, running out into the dark alleys of the ghetto

and knocking down those who got in his way, until the rabbi caught up with him and removed the tablet.

At once the creature fell lifeless. All that was left of him is the dwarfish clay figure that may be seen today in the New Synagogue.

Eleazar of Worms has preserved the secret formula for making a Golem. The procedures involved cover some twenty-three folio columns and require knowledge of the "alphabets of the

221 gates," which must be recited over each of the Golem's organs. The word emet, which means "truth," should be marked on its forehead; to destroy the creature, the first letter must be obliterated,

forming the word met, whose meaning is "death."

V/v Golem.

Borges Golem

Note:

Trong 1 bài viết hồi còn giữ mục Tạp Ghi cho tờ

Văn Học, Gấu có đi 1 bài về Borges, từ 1 cái

nguồn tiếng Tẩy, và có dịch từ Golem, là Phôi

Thai.

Nhảm!

Golem là tên 1 con vật tưởng tượng, và

nó có nghĩa - "Golem" was the name given the

man created out of a combination of letters; the word literally means"

an amorphous or lifeless substance." - và là tên 1 bài

thơ của Borges.

Để tạ lỗi , lần này,

đi 1 bài trong Những Con Vật Tưởng Tượng, trong có

con “Golem”, và 1 bài thơ của Borges, có tên

là Golem.

http://www.tanvien.net/tgtp/tgtp11_borges_toi.html

Phôi

thai

Ở Crayle, người Hy-lạp - liệu anh ta có lầm

không? -

Khi nói chữ là mẹ của sự vật:

Trong những con chữ hồng có mùi

thơm của hoa hồng,

Và dòng Nil luồn lách qua những

con chữ của từ Nil.

Vậy thì có một Cái Tên

khủng khiếp, từ đó yếu tính

của Thượng Đế được mã hóa - và

đó là một từ của con người,

Bảng mẫu tự đánh vần, bàn tay ghi

lại;

Kẻ nói lên có Sức Mạnh-Toàn

Năng.

Những ngôi sao biết Cái

Tên này. Adam cũng vậy,

Ở Khu Vườn; nhưng liền đó, anh ngỡ ngàng

và hoang mang:

Tội lỗi đục gỉ anh ta, những người thần bí

giáo bảo vậy;

Mọi dấu vết đến đây là ngưng. Như thế

đấy.

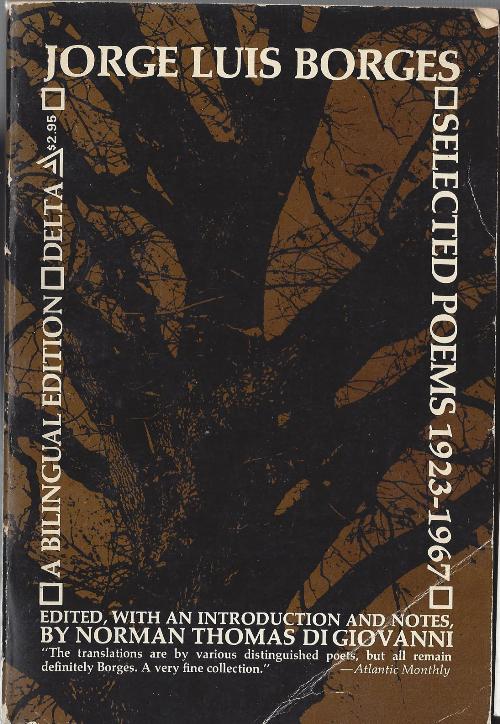

Jorge Luis Borges Thi Phẩm (1925-1965).

(Theo bản tiếng Pháp của Nestor Ibarra, Gallimard).

(1)

(1)

LE GOLEM

Dans Cratyle, le Grec - et se trornperait-il ? _

Dit que le mot est l'archétype de la chose:

Dans les lettres de rose embaume la fleur rose,

Et le Nil entre en crue aux lettres du mot Nil.

Un Nom terrible existe donc, par quoi l'essence

De Dieu même est chiffrée - et c'est un

mot humain,

Qu'épelle l'alphabet, que peut tracer la main;

Celui qui le prononce a la Toute-Puissance.

Les étoiles savaient ce Nom. Adam aussi,

Au Jardin; mais bientôt il s'étrange et se

brouille :

Le péché, disent les cabalistes, le rouille

;

Toute trace s'en perd à la fin. C'est ainsi.

Mais la candeur de l'homme et sa soif de merveilles

Et son art sont sans fond. Un jour, le peuple élu

Tenta de retrouver le vocable absolu ;

Toute la juiverie y consumait ses veilles.

C'est ici que Juda Léon va survenir,

Vive et verte mémoire, et non point ombre vague

A peine insinuée au vague devenir :

II est resté, Juda Léon, rabbin de Prague.

Juda Leon saura ce que Dieu sait. Brulé

De génie, il ajoute, il retranche, il permute

Les lettres - et l'emporte en fin de haute lutte.

II a trouvé Ie Nom. Et ce Nom est la Clé,

Est l'Echo, le Palais, et l'Hôte, et les Fenêtres.

Un pantin faconné d'une grossière main.

Par le Nom recoit vie: il connaitra demain

Les arcanes du Temps, de l'Espace et des Lettres.

Levant sur l'univers des regards somnolents,

L'hominien percut des formes confondues

A des couleurs, et dans une rumeur perdues ;

Novice, il s'essayait à des gestes tremblants.

II se sentit bien tôt prisonnier, comme un homme,

D'un sonore filet: l'Après et l'Aujourd'hui,

Et la Droite et la Gauche et le Plus et le Comme,

Le Maintenant, le Cependant, le Moi, le Lui.

Mais comment désigner la rude créature?

Le cabaliste-Dieu la sumomma Golem.

(Tout ce que je rapporte est constant, et figure

En quelque endroit du docte ouvrage de Scholem.)

Voici mon pied. ton pied ... Patient

pédagogue,

Le rabbin au Golem apprenait l'univers.

II se passa trois ans avant que le pervers

Sut balayer tant bien que mal la synagogue.

Fallait-il mieux écrire ou mieux articuler

Le Nom? Quelque bévue avait été commise

:

Haute sorcellerie à la fin compromise,

Le candidat humain n'apprit pas à parler.

Parcourant le reduit et sa brume morose? .

Ses yeux allaient cherchant ceux du magicien ; .

Et c'était un regard moins d'homme que de chien;

Si les choses voyaient, moins de chien que de chose.

Je ne sais quoi de lourd, d'abrupt chez le Golem

Faisait fuir sur ses pas le chat de la voisine.

(II n'est pas question de ce chat dans Scholem ;

Cependant, a travers les ans, je le devine.)

Filial, Ie Golem mimait l'officiant,

Et tel son dieu vers Dieu levait ses paumes graves;

Parfois d'orientaux salamalecs concaves

Longuement l'abimaient, stupide et souriant.

Le rabbin contemplait son oeuvre avec tendresse,

Mais non sans quelque horreur. Je fus bien avisé,

Pensait-il, d'engendrer ce garcon malaisé

Et de quitter l'Abstention, seule sagesse !

Fallait-il ajouter un symbole nouveau

A la succession intarissable et vaine ?

Une autre cause, un autre effet, une autre peine

Devaient-ils aggraver l'eternel echeveau ?

A l'heure où passe un doute à travers l'ombre

vague

Sur le pénible enfant son regard s'arrêtait.

Saurons-nous quelque jour ce que Dieu ressentait

Lorsque ses yeux tombaient sur son rabbin de Prague?

1958.

Trong những con chữ hồng

có mùi thơm của hoa hồng

Ta mơ tưởng 1 thế giới, ở đó, con người có

thể chết vì 1 cái dẩu phảy, Cioran phán

Gấu, chết vì một từ!

Vẫn chuyện chết vì cái

dấu phảy

Lạ, hiếm, phong trần, tã:

Vớ được tại tiệm sách cũ

THE GOLEM,

p. 111

Joshua Trachtenberg, in Jewish Magic and Superstition, writes that

the German Hasidim used "the word golem (literally, shapeless or lifeless

matter) to designate a homunculus created by the magical invocation of names,

and the entire cycle of golem legends may be traced back to their

interest."

Line 20. Though Judah Low, the seventeenth-century

Jewish rabbi from Prague, is credited with making the Golem, according to

Trachtenberg the "legends of the golem were transferred ... to R. Judah

Low b. Bezalel, without any historical basis." It turns out that John Hollander,

the poem's translator, is a descendant of Rabbi Low (or Loew); after making

his translation, Hollander was inspired to write his own Golem poem, "Letter

to Borges: A Propos of the Golem," which admirably complements the translation.

Hollander's poem is printed in his book The Night Mirror.

39. Gershom Scholem is the distinguished Jewish scholar

and author of Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism.

Borges' interest in the legend of the Golem dates from

an early acquaintance with Gustav Meyrink's Der Golem, the first prose

work in German Borges ever read. See Borges' article on "The Golem" in The

Book of Imaginary Beings, pp. 112-14.

Borges was named Director of the Argentine National Library after the

fall of Peron in 1955.

Line 37. Paul Groussac (1848-1929) had been a former

director of the Biblioteca Nacional and was also a historian and critic

whose prose style Borges has greatly admired. A short eulogy, written after

Groussac's death, is collected in Borges' Discusión

After writing the poem, Borges discovered that Jose Marmol, the nineteenth-century

poet and novelist who directed the National Library until his death in 1871,

had also gone blind.

Note: Nhân khoe câu văn thần sầu...

BURGIN: I've been wondering. I know you like "The Gifts" and “The Other Tiger." Do you have any other favourite poems?

BORGES: The poems I've written or the poems I've read?

BURGIN: No, the poems you've written.

BORGES: Yes, I think that quite the best poem is the poem called "El golem." Because "El golem," well, first, Bioy Casares told me it's the one poem where humour has a part. And then the poem is more or less an account of how the golem was evolved, and then there is a kind of parable because one thinks of the golem as being very clumsy, no? And the rabbi is rather ashamed of him. And in the end, it is suggested that as the golem is to the magician, to the cabalist, so is a man to God, no? And that perhaps God may be ashamed of mankind as the cabalist was ashamed of the golem. And then I think that in that poem you may also find a parable of the nature of art. Though the rabbi intended something beautiful, or very important, the creation of a man, he only succeeded in creating a very clumsy doll, no? A kind of parody of mankind. And then I like the last verses:

En la hora de angustia y de luz vaga,

en su Golem los ojos detenia.

Quien nos dira las cosas que sentia

Dios, al mirar a su rabino en Praga?

At the hour of anguish and vague light,

He would rest his eyes on his Golem.

Who can tell us what God felt,

As He gazed on His rabbi in Prague?

I think that's one of my best poems.

Note: Trong 1 bài viết hồi còn giữ mục Tạp Ghi cho tờ Văn Học, Gấu có đi 1 bài về Borges, từ 1 cái nguồn tiếng Tẩy, và có dịch từ Golem, là Phôi Thai.

Nhảm!

Golem là tên 1 con vật tưởng tượng, và nó có nghĩa - "Golem" was the name given the man created out of a combination of letters; the word literally means" an amorphous or lifeless substance." - và là tên 1 bài thơ của Borges.

Để tạ lỗi , lần này, đi 1 bài trong Những Con Vật Tưởng Tượng, trong có con “Golem”, và 1 bài thơ của Borges, có tên là Golem.

Ở Crayle, người Hy-lạp - liệu anh ta có lầm không? -

Khi nói chữ là mẹ của sự vật:

Trong những con chữ hồng có mùi thơm của hoa hồng,

Và dòng Nil luồn lách qua những con chữ của từ Nil.

Vậy thì có một Cái Tên khủng khiếp, từ đó yếu tính

của Thượng Đế được mã hóa - và đó là một từ của con người,

Bảng mẫu tự đánh vần, bàn tay ghi lại;

Kẻ nói lên có Sức Mạnh-Toàn Năng.

Những ngôi sao biết Cái Tên này. Adam cũng vậy,

Ở Khu Vườn; nhưng liền đó, anh ngỡ ngàng và hoang mang:

Tội lỗi đục gỉ anh ta, những người thần bí giáo bảo vậy;

Mọi dấu vết đến đây là ngưng. Như thế đấy.

Jorge Luis Borges Thi Phẩm (1925-1965).

(Theo bản tiếng Pháp của Nestor Ibarra, Gallimard). (1)

Dans Cratyle, le Grec - et se trornperait-il ? _

Dit que le mot est l'archétype de la chose:

Dans les lettres de rose embaume la fleur rose,

Et le Nil entre en crue aux lettres du mot Nil.

Un Nom terrible existe donc, par quoi l'essence

De Dieu même est chiffrée - et c'est un mot humain,

Qu'épelle l'alphabet, que peut tracer la main;

Celui qui le prononce a la Toute-Puissance.

Les étoiles savaient ce Nom. Adam aussi,

Au Jardin; mais bientôt il s'étrange et se brouille :

Le péché, disent les cabalistes, le rouille ;

Toute trace s'en perd à la fin. C'est ainsi.

Mais la candeur de l'homme et sa soif de merveilles

Et son art sont sans fond. Un jour, le peuple élu

Tenta de retrouver le vocable absolu ;

Toute la juiverie y consumait ses veilles.

C'est ici que Juda Léon va survenir,

Vive et verte mémoire, et non point ombre vague

A peine insinuée au vague devenir :

II est resté, Juda Léon, rabbin de Prague.

Juda Leon saura ce que Dieu sait. Brulé

De génie, il ajoute, il retranche, il permute

Les lettres - et l'emporte en fin de haute lutte.

II a trouvé Ie Nom. Et ce Nom est la Clé,

Est l'Echo, le Palais, et l'Hôte, et les Fenêtres.

Un pantin faconné d'une grossière main.

Par le Nom recoit vie: il connaitra demain

Les arcanes du Temps, de l'Espace et des Lettres.

Levant sur l'univers des regards somnolents,

L'hominien percut des formes confondues

A des couleurs, et dans une rumeur perdues ;

Novice, il s'essayait à des gestes tremblants.

II se sentit bien tôt prisonnier, comme un homme,

D'un sonore filet: l'Après et l'Aujourd'hui,

Et la Droite et la Gauche et le Plus et le Comme,

Le Maintenant, le Cependant, le Moi, le Lui.

Mais comment désigner la rude créature?

Le cabaliste-Dieu la sumomma Golem.

(Tout ce que je rapporte est constant, et figure

En quelque endroit du docte ouvrage de Scholem.)

Voici mon pied. ton pied ... Patient pédagogue,

Le rabbin au Golem apprenait l'univers.

II se passa trois ans avant que le pervers

Sut balayer tant bien que mal la synagogue.

Fallait-il mieux écrire ou mieux articuler

Le Nom? Quelque bévue avait été commise :

Haute sorcellerie à la fin compromise,

Le candidat humain n'apprit pas à parler.

Parcourant le reduit et sa brume morose? .

Ses yeux allaient cherchant ceux du magicien ; .

Et c'était un regard moins d'homme que de chien;

Si les choses voyaient, moins de chien que de chose.

Je ne sais quoi de lourd, d'abrupt chez le Golem

Faisait fuir sur ses pas le chat de la voisine.

(II n'est pas question de ce chat dans Scholem ;

Cependant, a travers les ans, je le devine.)

Filial, Ie Golem mimait l'officiant,

Et tel son dieu vers Dieu levait ses paumes graves;

Parfois d'orientaux salamalecs concaves

Longuement l'abimaient, stupide et souriant.

Le rabbin contemplait son oeuvre avec tendresse,

Mais non sans quelque horreur. Je fus bien avisé,

Pensait-il, d'engendrer ce garcon malaisé

Et de quitter l'Abstention, seule sagesse !

Fallait-il ajouter un symbole nouveau

A la succession intarissable et vaine ?

Une autre cause, un autre effet, une autre peine

Devaient-ils aggraver l'eternel echeveau ?

A l'heure où passe un doute à travers l'ombre vague

Sur le pénible enfant son regard s'arrêtait.

Saurons-nous quelque jour ce que Dieu ressentait

Lorsque ses yeux tombaient sur son rabbin de Prague?

Trong những con chữ hồng có mùi thơm của hoa hồng

Ta mơ tưởng 1 thế giới, ở đó, con người có thể chết vì 1 cái dẩu phảy, Cioran phán

Gấu, chết vì một từ!

Vẫn chuyện chết vì cái dấu phảy

Manguel đi 1 bài thần sầu, về bài thơ của Borges và về từ Golem, trong Packing My Library

Trong cuốn "Packing My Library", Manguel đi 1 đường dài về từ này. Post sau đây:

But there is more. Not only did God, according to Scripture, limit the power of our words: our other powers of creation were also censored. The Second Commandment of the Decalogue reads, "Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in the heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth." Though the commandment carries on to say that "thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the Lord thy God am a jealous God," it is the first part of the prohibition that long presented a problem for believers. Did God forbid only the creation of graven images of worship, or did his commandment extend to the creation of any image, any representation, any art by any means whatsoever, stone or color or words? Psalm 97 glosses this commandment: "Confounded be all they that serve graven images, that boast themselves of idols." In the eighteenth century, the celebrated Hassidic master Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav explained the prohibition as follows:

"The idol is destined to come and spit in the face of those who worship it and put them to shame, then bow before the Holy One, blessed be He, and cease to exist." Rabbi Nah- man did not pronounce himself specifically on the acts of sculpting, painting, and fiction writing, but a condemnation of these crafts is implicit in his prophecy.

Rabbinical commentators, and of course artists and writers, have pondered the question ever since. To a certain extent, from a biblical perspective, the history of the human imagination can be seen as the history of the debate on this peculiar interdiction. Is creation a permissible endeavor within the human scope, or are we condemned to fail because all art, since it is human and not divine, carries within it its own failure? God says he is a jealous God: Is he also a jealous artist? According to a Talmudic commentary quoted by Louis Ginzberg in “Legends of the Jews”, the serpent said to Eve in the Garden: "God Himself ate first of the fruit of the tree, and then He created the world. Therefore doth He forbid you to eat thereof, lest you create other worlds. Because everyone knows that 'artisans of the same guild hate one another." It is tempting for artists and writers to believe that they are in the same guild as the one who created them and granted them their creative powers.

One of the most explicit versions of this paradox is illustrated in the legend of the Golem, which I believe can serve as a metaphor for the library. “Golem” is a word that first appears in Psalm 139: 'Thine eyes did see my ‘golem’." According to Rabbi Eliezer, writing in the first century CE; the word ‘golem’ means "an unarticulated lump." The eighteenth-century legend of the Golem, this "unarticulated lump," tells of how the Maharal of Prague (an acronym for Morenu Harav Rabbi Laib, "our teacher Rabbi Loew") created a creature out of clay to protect the Jews from pogroms. On the forehead of the creature, Rabbi Loew wrote the word ‘emet’, "truth," and this enabled the creature to come to life and assist the rabbi in his daily chores. Later, however, the Golem escaped his master's control and wrought havoc in the ghetto, and Rabbi Loew was obliged to return it to the dust by effacing the first letter of ‘emet’, so that the word now read met, "death."

The Golem has prestigious ancestors. In a Talmudic passage of the Sanhedrin, it is stated that in the fourth century C.E., the Babylonian teacher Rava created a man out of clay and sent it to Rabbi Zera, who tried to converse with it, and when he saw that the creature could not utter a single word, he said to it, "You belong to the spawn of wizards; return to the dust." Immediately the creature crumbled into a shapeless heap. Another passage explains that in the third century, two Palestinian masters, Rabbi Haninah and Rabbi Oshea, with the help of the “Sefer Yeizirah”, or Book of Creation, brought to life a calf every Sabbath eve, which they then cooked for dinner.

Inspired by the eighteenth-century legend of Rabbi Loew, in 1915 the Austrian writer Gustav Meyrink published “The Golem”, a fantastic novel about a creature who appears every thirty-three years at the unreachable window of a circular room without doors in the Prague ghetto. Meyrink's novel was to have an unexpected offspring. That same year, the sixteen-year-old Jorge Luis Borges, trapped with his family in Switzerland during the war, read Meyrink's “Golem” in German and was enthralled by its haunting atmosphere. "Everything in the book is uncanny," he would later write, "even the monosyllables of the table of contents: Prag, Punsh, Nacht, Spuk, Licht ... " Borges saw in Meyrink's “Golem”, "a fiction made up of dreams that enclose other dreams," and allowed its fantastic vision of the world to lay the foundations for much of his future fiction.

More than forty years later, in 1957, Borges included the Golem in an early version of his “Book of Imaginary Beings”; a year later he told the story of Rabbi Loew in what was to become one of his most famous poems, first published in the Buenos Aires magazine Davar in the winter of 1958. Afterwards, Borges included the Golem poem in his “Personal Anthology”, placing it before a short text titled "Inferno, I:32," which considers, from different perspectives, the same existential question concerning the limits of creation. In the poem, Rabbi Loew wonders why he was driven to fashion this "apprentice of man" and what might be the meaning of his creature; in the text on Dante's “Inferno”, the panther that appears at the beginning of the poem and then the dying poet himself both learn and afterwards forget why it is that they have been created. Borges's "Golem" ends with this quatrain:

In the hour of anguish and dim light

The rabbi looked in awe upon his Golem.

Who will tell us what was felt by God

Looking upon his own rabbi in Prague?

The theme of the Golem haunted Borges for many years. When he visited Israel in 1969, he asked to meet the famous scholar of Jewish mysticism Gershom Scholem, whose name he had used in the poem "as the only possible word to rhyme with 'Golem' in Spanish." Their conversation, I was told, centered on the Jewish notion of permissible creation. Like the ancient biblical commentators, Borges and Scholem debated the fundamental question: To what success can an artist aspire? How can a writer achieve his purpose when all he has at his disposal is the imperfect tool of language? And above all: What is created when an artist sets out to create? Does a new, forbidden world come into being or is a dark mirror of this world lifted up for us to gaze in? Is a work of art a lasting reality or an imperfect lie? Is it a living Golem or a dead handful of dust? How can the Jews accept that at the same time God has granted them both the gift of creation and the prohibition to use it? And finally, even if there were an answer to these questions, can we know it? Scholem reminded Borges of Kafka's unappealable dictum: "If it had been possible to build the Tower of Babel without climbing it, it would have been allowed."

Jorge Luis Borges died in Geneva at 7:47 a.m., on 14 June 1986. As a special favor, the Administrative Council of Geneva decided to grant him permission to be buried in the cemetery of Plainpalais, reserved for the great and famous Swiss, since Borges had often spoken of Geneva as "my other homeland." In memory of Borges's grandmothers, one Catholic and the other Protestant, the service was read by Father Pierre Jacquet and Pastor Edouard de Montmollin. Pastor Montmollin's address judiciously opened with the first verse of the Gospel of John. "Borges," said Pastor Montrnollin, "was a man who unceasingly searched for the right word, the term that would sum up the whole, the final meaning of things," and went on to explain that, as the Good Book taught us, a man can never reach that word by his own efforts. As John made clear, it is not we who discover the Word, but the Word that reaches us. Pastor Montmollin summed up precisely Borges's literary credo: the writer's task is to find the right words to name the world, knowing all the while that these words are, as words, unreachable. Words are our only tools both to lend and to recover meaning and, at the same time, they allow us to understand that meaning, they show us that it lies precisely beyond the pale of words, just on the other side of language. Translators, perhaps more than any other wordsmiths, know this: whatever we build out of words can never seize in its entirety the desired object. The Word that is in the beginning names but can never be named.

Throughout his life, Borges explored and tried out this truth. From his first readings in Buenos Aires to the final writings dictated on his deathbed in Geneva, every text became, in his mind, proof of the literary paradox of being named without quite naming anything into being. Ever since his adolescence, something in every book he read seemed to escape him, like a wayward monster, promising, however, a further page, a greater epiphany at the next reading. And something in every page he wrote forced him to confess that the author was not the ultimate master of his own creation, of his Golem. This double bind, the promise of revelation that every book grants its reader and the warning of defeat that every book gives its writer, lends the literary act its constant fluidity.

For Borges, this fluidity lends both richness and an element of tragedy to Dante's "Commedia". According to Borges, Dante attempted to create a universe of words in which the poet is absolute master: a world in which he can enjoy the love of his adored Beatrice, converse with his beloved Virgil, renew friendships with absent friends, reward with a place in heaven those he deems worthy of reward, and take revenge on his enemies by condemning them to hell. The ancient dictum "Nomina sunt consequentia rerum," "words are the fruit of things," can work both ways, as the Kabbalists taught, basing their belief on the Adam story in Genesis. If words exist because they correspond to existing things, then things might exist because there are words to name them. And yet, in literature, things do not work out that way. Literature follows rules that override the rules of words and the rules of reality. "Each literary work entrusts to its writer the form that it is seeking," Borges wrote in the preface to his last book, “Los conjurados”. "Entrusts," he wrote; he could have written "commands." He could also have added that no writer, not even Dante, can fully accomplish the command.

For Borges, the “Commedia”, the most perfect of human literary endeavors, was nevertheless a failed creation because it failed to become what the author intended. The Word that breathes life (both Borges and Dante realized) is not equivalent to the living creature who breathes the word: the word that remains on the page, the word that, while imitating life, is incapable of being life. Plato made Socrates decry the creations of artists and poets for that very reason: art is imitation, never the real thing. If success were possible (it is not) the universe would become redundant. The most to which we can aspire is an inexpressible epiphany, like the one that rewards Dante at the end of his journey, at which "high fantasy loses its power" and will and desire turn over like a perfect wheel, moved by love.

Whether because of the imperfection of our tools or the imperfection of ourselves, whether because of the jealousy of the Godhead or his concern with our indulging in redundant tasks, the ancient prohibition of the Decalogue continues to serve as warning and incitement. The dusty and unsatisfactory Golem that still haunts our dreams through the dark alleyways of Prague is, after all, the uttermost achievement to which our crafts can aspire: bringing the dust to life and having it do our bidding. When the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, Israel, built its first computer, Gershom Scholem suggested that it be named Golem I.

Our creations, our Golems or our libraries, are at best things that suggest an approximation to a copy of our blurry intuition of the real thing, itself an imperfect imitation of an ineffable archetype. This achievement is our unique and humble prerogative. The only art that is synonymous with reality is (according to Dante and Borges and the Talmudic scholars) that of God. Gazing upon the pathway to Eden, sculpted by God himself in the Purgatory of the Proud, Dante says that "he saw not better than I saw, who saw the scenes in real life." God's reality and God's representation of reality are identical. Ours are not.

So it is that writers are made to play the role of a poor Golem, imperfectly created and capable only of imperfection, incompetent creatures casting in turn blasphemous doubts on the perfection of their Maker. In this game of shifting mirrors, the faulty Golem becomes our modest, faulty, all-embracing literature, and literature becomes the Golem. Yes, but an immortal Golem, because even when the first letter of the writing on its forehead is effaced, and ‘emet’ becomes met, a word still stands to name for us yet another unnamable: death itself, the end of all creation.

Jews believe that humans are made of time, that a ritual continuity flows through their veins reaching back to the drawn-out time of Abraham. Perhaps it is for that reason that for Jews loss is not of the essence: the rhythm of life continues in spite of the disappearance of material things.

Jews, after all, are a nomad people, for whom leaving things behind is an everyday experience, for whom exile is a condition of being and settlement only a halt on the flight from Egypt. Jews, like Moses, are always within sight of the Promised Land but never there, even after they have reached Zion-because even though God promised Moses a land destined for him, that land must remain forever unreachable, like Kafka's Castle. The curse of the Wandering Jew who can never rest until the Christian Second Coming is merely the confirmation of a natural state of being among Jews: the Jew must wait for the Second Coming because, in the Jew's heart, the First Coming has not yet taken place.

And given the nature of the world, it will not take place any time soon.

This is the paradox of all our arts and crafts: to exist between these two mandates, like ambitious but imperfectly gifted Kabbalists. Jews live in the grip of an immemorial and contradictory injunction: on one hand, not to build things that might lead to idolatry and complacency; on the other, to build things worthy of adoration-to reject the serpent's temptation to aspire to be gods and also to reflect God's creation back to him in luminous pages that conjure up his world; to accept that the limits of human creation are hopelessly unlike the limitless creation of God, and yet to strive continuously to attain those limits to set up something that aspires to an order, a imperfect dream of order, a library.

ALBERTO MANGUEL: “PACKING MY LIBRARY”

Comments

Post a Comment