Zweig vs Vo Phien

Zweig

Tờ Books có

hai bài, một, dịch bài trên LRB, "Zweig, ce pepsi de la littérature",

và một, trong số đặc biệt về đời riêng của những nhà văn, la vie privée

de

l'écrivain, đọc cuốn tiểu sử của Zweig, bản tiếng Đức, của Oliver

Matuschek.

Ông này cũng chê Zweig, tố cáo Zweig đã quay lưng trước đồng nghiệp,

trước Nazi.

Theo ông, những truyện ngắn của Zweig cho thấy 1 con người bị sex hành

hạ, và là

chính tác giả.

Truyện thần sầu của Zweig, với Gấu, là Người Chơi Cờ, được viết trước khi Zweig mất ít lâu.

Thời gian ở Brésil, ông không biết làm gì, bèn mê cờ, và mê đọc những trận cờ nổi tiếng trong chốn giang hồ.

Truyện thần sầu của Zweig, với Gấu, là Người Chơi Cờ, được viết trước khi Zweig mất ít lâu.

Thời gian ở Brésil, ông không biết làm gì, bèn mê cờ, và mê đọc những trận cờ nổi tiếng trong chốn giang hồ.

Những nhân vật

tiểu thuyết hiện đại đều bước ra từ cái bóng của Don Quixote; ta có thể

lập lại,

với những nhân vật của Võ Phiến: họ đều bước ra từ Người Chơi Cờ. Tôi không hiểu,

ông đã đọc nhà văn Đức, trước khi viết, nhưng khí hậu 1945, Bình Định,

và một

Võ Phiến bị cầm tù giữa lớp cán bộ cuồng tín, đâu có khác gì ông B.

(không hiểu

khi bị bắt trong vụ chống đối, Võ Phiến có ở trong tình huống đốt vội

đốt vàng

những giấy tờ quan trọng...). Nhân vật "cù lần" trong Thác Đổ Sau

Nhà, đã có một lần được tới Thiên Thai, cùng một cô gái trong một căn

lều, giữa

rừng, cách biệt với thế giới loài người, có một cái gì thật quen thuộc

với đối

thủ của ông B., tay vô địch cờ tướng nhà quê vô học, nhưng cứ ngồi

xuống bàn cờ

là kẻ thù nào cũng đánh thắng, đả biến thiên hạ vô địch thủ?

"Nhưng đây là con lừa Balaam", vị linh mục nhớ tới Thánh Kinh, về một câu chuyện trước đó hai ngàn năm, một phép lạ tương tự đã xẩy ra, một sinh vật câm đột nhiên thốt ra những điều đầy khôn ngoan. Bởi vì nhà vô địch là một người không thể viết một câu cho đúng chính tả, dù là tiếng mẹ đẻ, "vô văn hoá về đủ mọi mặt", bộ não của anh không thể nào kết hợp những ý niệm đơn giản nhất. Năm 14 tuổi vẫn phải dùng tay để đếm!

"Nhưng đây là con lừa Balaam", vị linh mục nhớ tới Thánh Kinh, về một câu chuyện trước đó hai ngàn năm, một phép lạ tương tự đã xẩy ra, một sinh vật câm đột nhiên thốt ra những điều đầy khôn ngoan. Bởi vì nhà vô địch là một người không thể viết một câu cho đúng chính tả, dù là tiếng mẹ đẻ, "vô văn hoá về đủ mọi mặt", bộ não của anh không thể nào kết hợp những ý niệm đơn giản nhất. Năm 14 tuổi vẫn phải dùng tay để đếm!

[Nhưng đây là Hồ Tôn Hiến,

lớp 1, chăn trâu!]

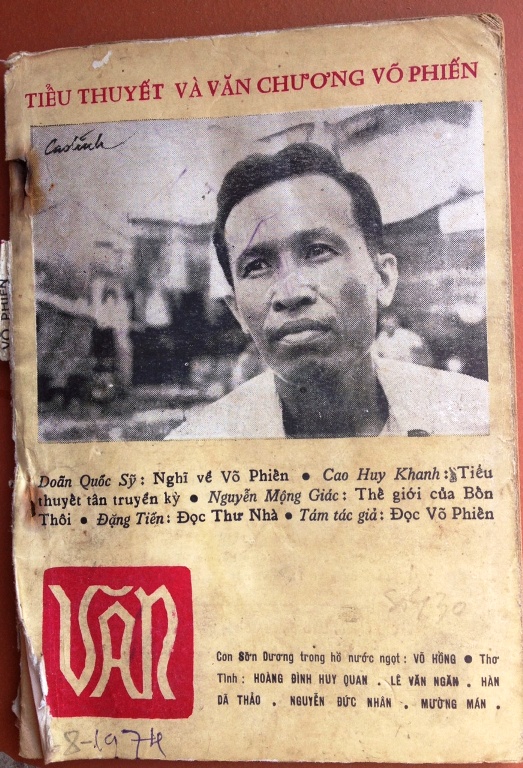

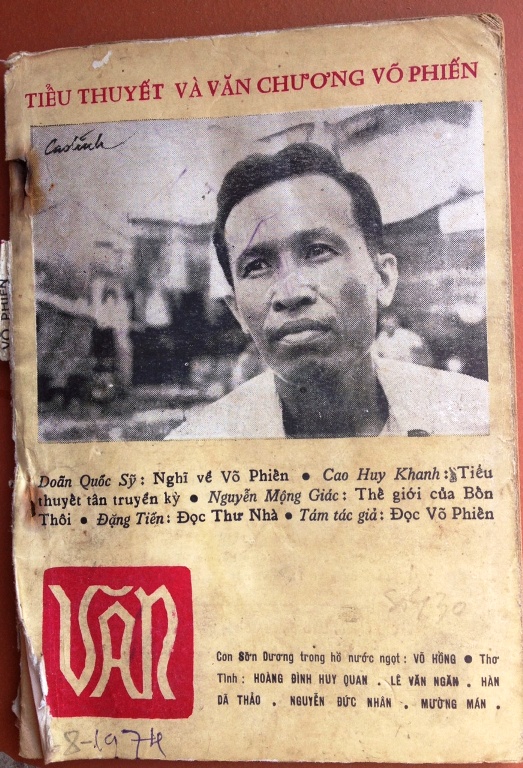

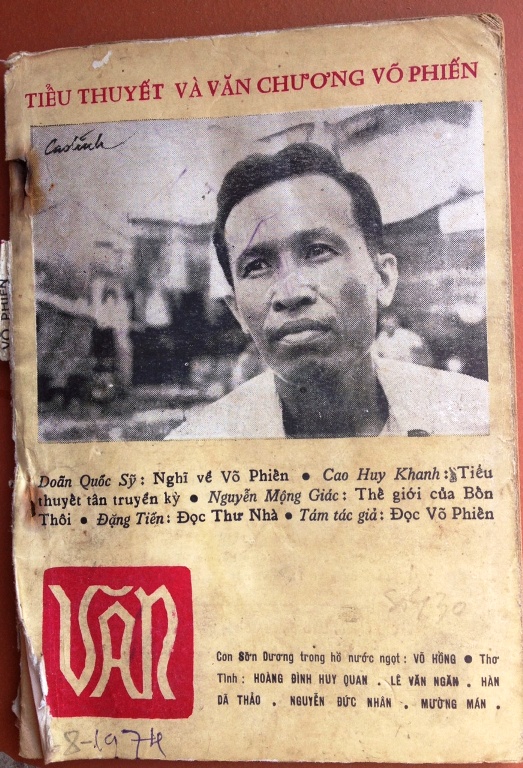

Tôi vội lục

lại tạp chí Văn số đặc biệt về Võ Phiến. May, tôi còn giữ....

Gấu đã từng,

sau khi xin lỗi ông nhóc con trên talawas, viết mail riêng, đề nghị ông

nhóc

chuyển cho coi lại bài viết cũ.

Ông đếch thèm trả lời.

Ông đếch thèm trả lời.

Sở dĩ ông ta “đi 1 đường

hờ

hững”, là vì yên chí lớn, chẳng thằng nào con nào còn tờ Văn, số về VP.

Ông nhóc không ngờ là trong nước bi giờ săn kho tàng nọc độc văn hóa Mỹ Ngụy ghê quá, còn hơn cơn sốt vàng của Mẽo, La Ruée vers l’or!

Ông nhóc không ngờ là trong nước bi giờ săn kho tàng nọc độc văn hóa Mỹ Ngụy ghê quá, còn hơn cơn sốt vàng của Mẽo, La Ruée vers l’or!

Nhờ

“Cơn Sốt Vàng”, Gấu có lại được những bài viết không bao giờ nghĩ lại

được nhìn

lại chúng.

Cám Ơn Các Bạn Nhà Văn VC thân mến của GCC!

Nhìn thấy mấy trang TSVC, như nhìn thấy bạn Joseph Huỳnh Văn ngày nào!

Cám Ơn Các Bạn Nhà Văn VC thân mến của GCC!

Nhìn thấy mấy trang TSVC, như nhìn thấy bạn Joseph Huỳnh Văn ngày nào!

Tks. Many Tks. NQT

Truyện ngắn Võ Phiến

Trong bài viết về VP, của Gấu, có câu, của Faulkner, tác phẩm lớn chỉ xuất hiện khi nỗi lo sợ tạm ngưng.

Tuyệt quá, nhưng chán quá, không biết thuổng từ cuốn nào của sư phụ!

Tôi đọc Võ Phiến rất sớm,

một phần là do ông

anh rể, Nguyễn Hoạt. Ông lúc đó cùng bạn bè chủ trương tờ nhật báo Tự

Do, và

sau đó, còn làm nhà xuất bản, nơi đã từng in cuốn Kể Trong Đêm Khuya

(?) của Võ

Phiến. Tôi đọc VP trước đó ít lâu, khi ông anh mang về nhà mấy tờ báo

mỏng

dính, in ấn lem nhem, như tự in lấy, tờ Mùa Lúa Mới, phát hành đâu từ

miền

Trung. (1) Tôi chỉ nhớ cái thuở ban đầu làm quen những nhân vật của

ông, không

còn nhớ đã từng viết về ông, một phần là do, thời gian sau đó, tôi mải

mê, ngấu

nghiến đọc những tác giả, mà tôi hy vọng họ giúp tôi giải thích tại sao

sinh

ra, tại sao sống, tại sao chết, tại sao có cuộc chiến khốn khổ khốn nạn

đó...

Những tác giả, thí dụ như

Camus, mà câu văn sau

đây không thể nào gỡ ra khỏi ký ức, kể từ lần đầu tiên đọc nó, khi mới

lớn,

trong Sài Gòn...

Tôi lớn lên cùng với những

người của thế hệ

tôi, cùng những tiếng trống của Cuộc Chíến I, và lịch sử từ đó, không

ngừng chỉ

là sát nhân, bất công, và bạo lực...

[Nguyên văn câu tiếng Tây, hình như là như sau đây, tiếc rằng, không làm sao tìm lại được "nguyên con", để so sánh: J'ai grandi avec tous mes hommes de mon age, aux tambours de la première guerre, et l'histoire depuis, n'a pas cessé d'être meurtre, injustice, et violence..]

[Nguyên văn câu tiếng Tây, hình như là như sau đây, tiếc rằng, không làm sao tìm lại được "nguyên con", để so sánh: J'ai grandi avec tous mes hommes de mon age, aux tambours de la première guerre, et l'histoire depuis, n'a pas cessé d'être meurtre, injustice, et violence..]

Chỉ một phần thôi...

Lý do tôi không đọc Võ Phiến nữa, chính là nhờ ông, tôi lần ra một tác giả khác, giải quyết giùm cho tôi, một số câu hỏi mà những nhân vật của Võ Phiến không thể vượt qua được. Đó là Stefan Zweig....

Nhân vật của Võ Phiến rất giống nhân vật của Zweig. Tôi không hiểu ông đã từng đọc Zweig, trước khi khai sinh ra những Người Tù, Kể Trong Đêm Khuya, Thác Đổ Sau Nhà... với những con người phàm tục, bị cái libido xô đẩy vào những cuộc phiêu lưu tuyệt vời, khi thoát ra khỏi, lại nhờm tởm chính mình, nhờm tởm cái thân thể mình đã dính bùn, sau khi bị con quỉ cám dỗ.... Nhân vật của Zweig cũng y hệt như vậy, trừ một điều: họ đều muốn lập lại cái kinh nghiệm chết người khủng khiếp đó. Và cú thử thứ nhì, lẽ dĩ nhiên là thất bại, nhưng nhờ vậy, họ vẫn còn là người, vẫn còn đam mê, vẫn còn đủ sân si...

Cái đòn thứ nhì này, tôi gọi là đòn gia bảo, gia truyền, không thể truyền cho ai, bất cứ đệ tử nào, như trong Thuyết Đường cho thấy, Tần Thúc Bảo không dám dạy La Thành cú Sát Thủ Giản, mà La Thành cũng giấu đòn Hồi Mã Thương...

Trong truyện Ngõ Hẻm Dưới Ánh Trăng, anh chồng biển lận khiến cô vợ quá thất vọng bỏ đi làm gái. Anh chồng tìm tới nơi, lạy lục, than khóc, cô vợ mủi lòng quá, bèn quyết định từ giã thiên thai, trở về đời. Trong bữa ăn từ giã thiên thai, anh chồng không thể quên tính trời cho, tóm tay anh bồi đòi lại mấy đồng tiền tính dư, cô vợ chán quá, bỏ luôn giấc mộng tái ngộ chàng Kim.

Hay trong Người Chơi Cờ, nhân vật chính, nhờ chôm được cuốn thiên thư dạy chơi cờ, mà qua được địa ngục. Về đời, thần tiên đã căn dặn, chớ có chơi cờ nữa, nhưng làm sao không? Chơi lần sau, là đi luôn!

Nhân vật của Võ Phiến, sau cú đầu là té luôn, không gượng dậy được nữa. Thí dụ cái cô trong Thác Đổ Sau Nhà, gặp lại Người Tình Trong Một Đêm, bỗng tởm chính mình: Cớ sao lại ngã vào một tay cà chớn tới mức đó!

Hay nhân vật Toàn (?) yêu cô gái, con một tay công chức (?), thất tình, anh bỏ đi theo kháng chiến, thay cái "libido" bằng "cách mạng", cuối cùng chết mất xác, không thể trở về đối diện với chính mình, với người yêu đầu đời...

Ông bố cô gái, nếu tôi nhớ không lầm, thường viết thư sai con đưa tới mấy ông bạn cũ, để xin tiền. Lúc rảnh rỗi, hai cha con không biết làm gì, bèn đóng tuồng, con giả làm Điêu Thuyền, bố, Lã Bố...

Võ Phiến còn một truyện ngắn, không hiểu sau khi ra hải ngoại, ông có cho in lại không, đó là truyện một anh CS về thành, được trao công việc đi giải độc. Giải độc mãi, tới một bữa, anh nhận ra là thiên hạ chỉ giả đò nghe anh lảm nhảm tố cộng, nhưng thật sự là đang lo làm việc khác... Tôi không hiểu có phải đây là một thứ tự truyện hay không.

Lý do tôi không đọc Võ Phiến nữa, chính là nhờ ông, tôi lần ra một tác giả khác, giải quyết giùm cho tôi, một số câu hỏi mà những nhân vật của Võ Phiến không thể vượt qua được. Đó là Stefan Zweig....

Nhân vật của Võ Phiến rất giống nhân vật của Zweig. Tôi không hiểu ông đã từng đọc Zweig, trước khi khai sinh ra những Người Tù, Kể Trong Đêm Khuya, Thác Đổ Sau Nhà... với những con người phàm tục, bị cái libido xô đẩy vào những cuộc phiêu lưu tuyệt vời, khi thoát ra khỏi, lại nhờm tởm chính mình, nhờm tởm cái thân thể mình đã dính bùn, sau khi bị con quỉ cám dỗ.... Nhân vật của Zweig cũng y hệt như vậy, trừ một điều: họ đều muốn lập lại cái kinh nghiệm chết người khủng khiếp đó. Và cú thử thứ nhì, lẽ dĩ nhiên là thất bại, nhưng nhờ vậy, họ vẫn còn là người, vẫn còn đam mê, vẫn còn đủ sân si...

Cái đòn thứ nhì này, tôi gọi là đòn gia bảo, gia truyền, không thể truyền cho ai, bất cứ đệ tử nào, như trong Thuyết Đường cho thấy, Tần Thúc Bảo không dám dạy La Thành cú Sát Thủ Giản, mà La Thành cũng giấu đòn Hồi Mã Thương...

Trong truyện Ngõ Hẻm Dưới Ánh Trăng, anh chồng biển lận khiến cô vợ quá thất vọng bỏ đi làm gái. Anh chồng tìm tới nơi, lạy lục, than khóc, cô vợ mủi lòng quá, bèn quyết định từ giã thiên thai, trở về đời. Trong bữa ăn từ giã thiên thai, anh chồng không thể quên tính trời cho, tóm tay anh bồi đòi lại mấy đồng tiền tính dư, cô vợ chán quá, bỏ luôn giấc mộng tái ngộ chàng Kim.

Hay trong Người Chơi Cờ, nhân vật chính, nhờ chôm được cuốn thiên thư dạy chơi cờ, mà qua được địa ngục. Về đời, thần tiên đã căn dặn, chớ có chơi cờ nữa, nhưng làm sao không? Chơi lần sau, là đi luôn!

Nhân vật của Võ Phiến, sau cú đầu là té luôn, không gượng dậy được nữa. Thí dụ cái cô trong Thác Đổ Sau Nhà, gặp lại Người Tình Trong Một Đêm, bỗng tởm chính mình: Cớ sao lại ngã vào một tay cà chớn tới mức đó!

Hay nhân vật Toàn (?) yêu cô gái, con một tay công chức (?), thất tình, anh bỏ đi theo kháng chiến, thay cái "libido" bằng "cách mạng", cuối cùng chết mất xác, không thể trở về đối diện với chính mình, với người yêu đầu đời...

Ông bố cô gái, nếu tôi nhớ không lầm, thường viết thư sai con đưa tới mấy ông bạn cũ, để xin tiền. Lúc rảnh rỗi, hai cha con không biết làm gì, bèn đóng tuồng, con giả làm Điêu Thuyền, bố, Lã Bố...

Võ Phiến còn một truyện ngắn, không hiểu sau khi ra hải ngoại, ông có cho in lại không, đó là truyện một anh CS về thành, được trao công việc đi giải độc. Giải độc mãi, tới một bữa, anh nhận ra là thiên hạ chỉ giả đò nghe anh lảm nhảm tố cộng, nhưng thật sự là đang lo làm việc khác... Tôi không hiểu có phải đây là một thứ tự truyện hay không.

Lần trở lại đất bắc, tôi

gặp một ông rất có

uy tín, cả trong giới văn lẫn giới Đảng, (đã về hưu). Ông cho biết, vụ

VP bị CS

bắt là hoàn toàn có thiệt. Nhưng chuyện ông được tha, không phải như Tô

Hoài

cho rằng mấy anh đưa người ra bắc trong chiến dịch tập kết năm 1954 đã

bỏ sót,

mà do một tay tỉnh ủy (?) có máu văn nghệ, đã ra lệnh tha, cho về

thành....

Bài viết của PLP, khi đọc

lại, thì Gấu nhớ là đọc rồi, nhờ chi tiết “Bắt Trẻ Đồng Xanh”. Nhưng

nhờ đọc lại, thì mới để ý đến những nhận xét của PLP, thí dụ:

Thế giới “hay” nhất của VP

là cái hốt hoảng, phân vân, bỡ ngỡ của 1 khung trời vừa mới thoát xác:

đang ở trong vùng Cộng Sản, trở thành vùng Quốc Gia….

Có hai định nghĩa về nhà

văn, tưởng choảng nhau, nhưng lại bổ túc cho nhau, thế mới kỳ. Nhận xét

trên, của PLP ứng với định nghĩa, nhà văn là kẻ đến sau biến động. Và

vế ngược của nó: Nhà văn là 1 nhà tiên tri.

Có thể nói, thế giới văn chương Võ Phiến, có được là nhờ [đến sau] hiệp định 1954.

Nhưng, bây giờ đọc câu trên, thì lại nhìn ra tính tiên tri của nó: Thế giới “thảm” nhất của, không phải VP mà là cả Miền Nam: đang ở trong vùng Quốc Gia, trở thành vùng Cộng Sản!

Có thể nói, thế giới văn chương Võ Phiến, có được là nhờ [đến sau] hiệp định 1954.

Nhưng, bây giờ đọc câu trên, thì lại nhìn ra tính tiên tri của nó: Thế giới “thảm” nhất của, không phải VP mà là cả Miền Nam: đang ở trong vùng Quốc Gia, trở thành vùng Cộng Sản!

Một bài viết hay như thế,

đầy tính văn, tính sử, tính định mệnh như thế, mà anh nhóc con hạ bút:

"đành rằng, với cách viết hờ hững…”, tôi đếch coi thằng nào ra thằng nào!

"đành rằng, với cách viết hờ hững…”, tôi đếch coi thằng nào ra thằng nào!

[Nguyên văn: "Ngoài ra,

còn mục 'Ðọc Võ Phiến', gồm những trích đoạn từ bài viết của các nhà

văn: Phan Lạc Phúc, Mai Thảo, Ðỗ Tấn, cô Phương Thảo, Huỳnh Phan Anh,

Viên Linh, Nguyễn Quốc Trụ, và Nguyễn Ðình Toàn về một tác phẩm nào đó

của Võ Phiến. Tất cả các bài viết này đều đã được đăng báo, đâu đó."

(tr. 205).

Ðã đành, với cách viết hờ hững như thế, tôi không xem các bài viết hay các trích đoạn ấy có giá trị văn chương hay sử liệu gì quan trọng] (1)

Một ông “ôn con” như thế, mà bây giờ được "lịch sử", qua băng đảng, bộ lạc Cờ Lăng, trao trách nhiệm viết về văn học Miền Nam trước 1975, một nền văn học bất hạnh!

Ðã đành, với cách viết hờ hững như thế, tôi không xem các bài viết hay các trích đoạn ấy có giá trị văn chương hay sử liệu gì quan trọng] (1)

Một ông “ôn con” như thế, mà bây giờ được "lịch sử", qua băng đảng, bộ lạc Cờ Lăng, trao trách nhiệm viết về văn học Miền Nam trước 1975, một nền văn học bất hạnh!

Tôi vội lục lại tạp chí Văn số đặc biệt về Võ Phiến. May, tôi còn giữ....

Gấu đã từng,

sau khi xin lỗi ông nhóc con trên talawas, viết mail riêng, đề nghị ông

nhóc

chuyển cho coi lại viết cũ.

Ông đếch thèm trả lời.

Sở dĩ ông ta “đi 1 đường hờ hững”, là vì yên chí lớn, chẳng thằng nào con nào còn tờ Văn, số về VP.

Ông nhóc không ngờ là trong nước bi giờ săn kho tàng nọc độc văn hóa Mỹ Ngụy ghê quá, còn hơn cơn sốt vàng của Mẽo, La Ruée vers l’or!

Ông đếch thèm trả lời.

Sở dĩ ông ta “đi 1 đường hờ hững”, là vì yên chí lớn, chẳng thằng nào con nào còn tờ Văn, số về VP.

Ông nhóc không ngờ là trong nước bi giờ săn kho tàng nọc độc văn hóa Mỹ Ngụy ghê quá, còn hơn cơn sốt vàng của Mẽo, La Ruée vers l’or!

Nhờ

“Cơn Sốt Vàng”, Gấu có lại được những bài viết không bao giờ nghĩ lại

được nhìn

lại chúng.

Cám Ơn Các Bạn Nhà Văn VC thân mến của GCC!

Nhìn thấy mấy trang TSVC, như nhìn thấy bạn Joseph Huỳnh Văn ngày nào!

Cám Ơn Các Bạn Nhà Văn VC thân mến của GCC!

Nhìn thấy mấy trang TSVC, như nhìn thấy bạn Joseph Huỳnh Văn ngày nào!

Tks. Many Tks. NQT

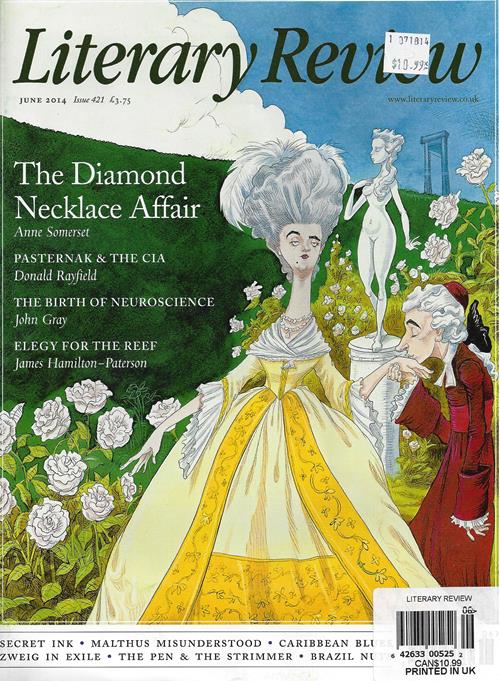

Trong bài “Now,

Voyager”, điểm cuốn “Lưu Vong Bất Khả: Stefan Zweig [ở tận cùng thế

giới], at

the End of the World", trên tờ Literary Review chúng

ta đang bàn tới, Evelyn

Juers cũng nhắc tới bài viết phạng Zweig tơi bời trên tờ LRB - nó khiến

tác giả

không dám đọc lại Zweig nữa, như chúng ta

vẫn thường sợ phải đọc lại 1 cuốn sách trước đó quá mê, nhưng cuốn "Lưu

Vong Bất

Khả" của Prochnik khiến ông an tâm, Zweig vẫn xứng đáng đọc.

Võ Phiến thì cũng thế!

Tin Văn sẽ dịch bài viết trên, và link bài viết trên LRB, ở đây:

Võ Phiến thì cũng thế!

Tin Văn sẽ dịch bài viết trên, và link bài viết trên LRB, ở đây:

Michael

Hofmann

The World of

Yesterday by Stefan Zweig, translated by Anthea Bell

Đọc bài điểm

cuốn tiểu sử của Zweig, “Lưu vong bất khả”, The Impossible Exile, thì Gấu hiểu

ra, tại làm sao mà tụi mũi lõ nói tiếng Anh chịu không nổi Zweig. Với

Zweig, Âu

Châu là nhà của ông. Gấu nhận ra điều này, khi viết về Võ Phiến, và gọi

ông là “nhà

văn Bình Định”, là theo nghĩa đó.

Với tôi, văn

chương Sài Gòn một thuở có một nhà văn bị thổi phồng về rất nhiều thứ:

tài

năng, tầm vóc, vân vân và vân vân.

Đó chính là Võ Phiến.

Đó chính là Võ Phiến.

Blog NL

Nhận xét trên,

theo Gấu không đúng. Trước 1975, Võ Phiến không được nhắc tới nhiều, so

với những

nhà văn ăn khách khác, thí dụ Sơn Nam, Bình Nguyên Lộc của Nam Kỳ, hay

Thanh Tâm

Tuyền, Mai Thảo, Doãn Quốc Sĩ, của Bắc Kỳ di cư, thí dụ. Nhưng không

phải là ông không có độc

giả, nhất

là về mặt tiểu thuyết, truyện ngắn, theo GCC, rất giống Zweig, ở rất

nhiều điểm.

Những nhận xét của tác giả bài điểm cuốn tiểu sử “Lưu Vong Bất Khả” về Zweig, trên tờ Literary Review có thể áp dụng vô VP: "Thương hiệu" của Zweig là “amok”, 1 từ của chính ông [Amok là tên 1 tác phẩm của Zweig, được dịch ra tiếng Việt là Người Khùng Mã Lai]:

They run amok!... All too often, demonic rapture grabs his readers by the throat. Cái sướng khùng điên, man rợ tóm lấy cổ độc giả, và bóp chặt!

Nhân vật của VP cũng cho chúng ta cái sướng khùng điên man dại đó!

Những nhận xét của tác giả bài điểm cuốn tiểu sử “Lưu Vong Bất Khả” về Zweig, trên tờ Literary Review có thể áp dụng vô VP: "Thương hiệu" của Zweig là “amok”, 1 từ của chính ông [Amok là tên 1 tác phẩm của Zweig, được dịch ra tiếng Việt là Người Khùng Mã Lai]:

They run amok!... All too often, demonic rapture grabs his readers by the throat. Cái sướng khùng điên, man rợ tóm lấy cổ độc giả, và bóp chặt!

Nhân vật của VP cũng cho chúng ta cái sướng khùng điên man dại đó!

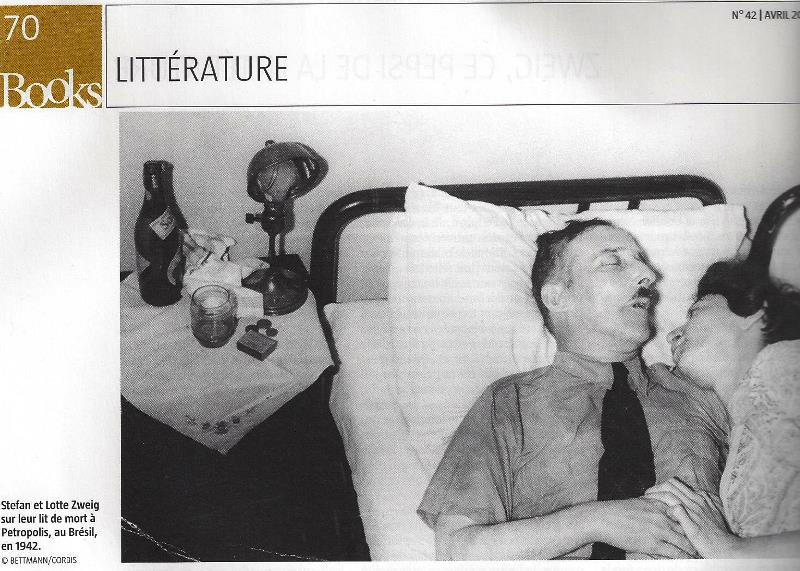

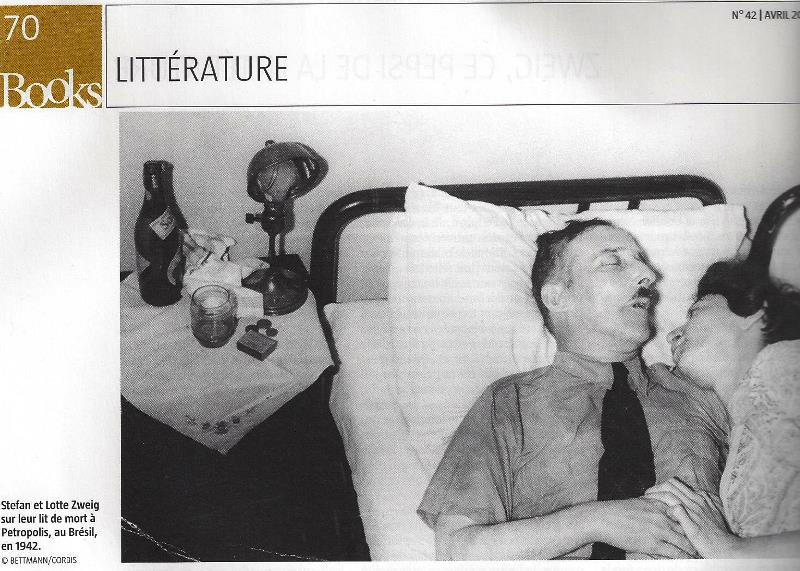

On February

23, 1942, Stefan Zweig and his young wife committed suicide together in

Petrópolis, Brazil. The following day, the Brazilian government held a

state

funeral, attended by President Getulio Vargas. The news spread rapidly

around

the world, and the couple’s deaths were reported on the front page of

The New

York Times. Zweig had been one of the most renowned authors of his

time, and

his work had been translated into almost fifty languages. In the eyes

of one of

his friends, the novelist Irmgard Keun, “he belonged to those that

suffered but

who would not and could not hate. And he was one of those noble Jewish

types

who, thinskinned and open to harm, lives in an immaculate glass world

of the

spirit and lacks the capacity themselves to do harm.”

The suicide

set off a surge of emotion and a variety of reactions. Thomas Mann, the

unquestioned leader of German-language writers in exile, made no secret

of his

indignation at what he considered an act of cowardice. In a telegram to

the New

York daily PM, he certainly paid tribute to his fellow writer’s talent,

but he

underscored the “painful breach torn in the ranks of European literary

emigrants by so regrettable a weakness.” He made his point even clearer

in a

letter to a writer friend: “He should never have granted the Nazis this

triumph, and had he had a more powerful hatred and contempt for them,

he would

never have done it.” Why had Zweig been unable to rebuild his life? It

wasn’t

for lack of means, as Mann pointed out to his daughter Erika.

This is the

subject of Georges Prochnik’s The Impossible Exile, a gripping,

unusually

subtle, poignant, and honest study. Prochnik attempts, on the basis of

an

uncompromising investigation, to clarify the motives that might have

driven to

suicide an author who still enjoyed a rare popularity, an author who

had just

completed two major works, his memoir, The World of Yesterday, and

Brazil: Land

of the Future. He had also finished one of his most startling novellas,

Chess

Story, in which he finally addressed the horrors of his own time,

proving that

his creative verve hadn’t been in the least undermined by his ordeals.

Recently

he had married a loving woman, nearly thirty years his junior. And he

had

chosen of his own free will to leave the United States and take refuge

in

Brazil, a hospitable nation that had fired his imagination.

Cái sự biến

VP thành… thần, là ở hải ngoại, khi ông

nhận được tiền của… Xịa, viết văn học sử

Miền Nam. Đám nhà văn hải ngoại, tên nào mà chẳng thèm vô… văn học sử!

Và khi VC muốn mua ông, tái bản sách của ông, dưới cái tên Tràng Thiên.

Tạm thôi, chờ thời, dùng đúng tên VP!

Và khi VC muốn mua ông, tái bản sách của ông, dưới cái tên Tràng Thiên.

Tạm thôi, chờ thời, dùng đúng tên VP!

Nhưng đám VC

thì chỉ dám thổi ba cái nhảm nhất của VP, với Gấu, là Tuỳ Bút, Tạp Ghi.

Có tên

còn phán, hơn hẳn Nguyễn Tuân!

Quá bậy. Tuỳ bút, ăn thua ở cái tâm nhiều lắm, nếu muốn viết hay. Khi tới đỉnh, là nó trở thành thứ văn chương “viết như không viết”. Ở hải ngoại, có 1 đấng nổi danh lắm, được khen lắm, Gấu không nêu tên, vì lại thêm 1 kẻ thù, nhưng mỗi lần Gấu đọc, là thấy ông này đang bặm môi làm nhà đạo đức, nhà đắc đạo, sau khi đã kinh qua… Lò Cải Tạo! Ông ta đã đi tù VC rồi mà, được VC ban cho cái bằng đã kinh qua [tốt nghiệp] Lò Cải Tạo, đã đắc đạo, đã không thù, không oán….

Kít!

Đâu có khác gì mấy tên VC nằm vùng!

Quá bậy. Tuỳ bút, ăn thua ở cái tâm nhiều lắm, nếu muốn viết hay. Khi tới đỉnh, là nó trở thành thứ văn chương “viết như không viết”. Ở hải ngoại, có 1 đấng nổi danh lắm, được khen lắm, Gấu không nêu tên, vì lại thêm 1 kẻ thù, nhưng mỗi lần Gấu đọc, là thấy ông này đang bặm môi làm nhà đạo đức, nhà đắc đạo, sau khi đã kinh qua… Lò Cải Tạo! Ông ta đã đi tù VC rồi mà, được VC ban cho cái bằng đã kinh qua [tốt nghiệp] Lò Cải Tạo, đã đắc đạo, đã không thù, không oán….

Kít!

Đâu có khác gì mấy tên VC nằm vùng!

Gấu nhớ hoài,

lần gặp lại 1 người bạn, khi mới ra được ngoài này. Anh thật mừng rỡ,

cho biết,

ông được vô văn học sử rồi! Gấu ngạc nhiên quá, tính hỏi, anh giúi cuốn

“Văn Học

Tổng Quan” của Võ Phiến vô tay, biểu, đọc đi.

Số này, có mấy

bài viết OK. Cái tiệm sách báo Tẩy dẹp luôn rồi. Gấu, theo lời chỉ dẫn

của bà

chủ tiệm, tới 1 tiệm có bán báo Tẩy. Lèo tèo một hai tờ. Hỏi sách Tẩy

lắc đầu,

làm gì có thứ đó ở đây!

Đọc bài điểm

cuốn tiểu sử của Zweig, “Lưu vong bất khả”, The Impossible Exile, thì Gấu hiểu

ra, tại làm sao mà tụi mũi lõ nói tiếng Anh chịu không nổi Zweig. Với

Zweig, Âu

Châu là nhà của ông. Gấu nhận ra điều này, khi viết về Võ Phiến, và gọi

ông là “nhà

văn Bình Định”, là theo nghĩa đó.

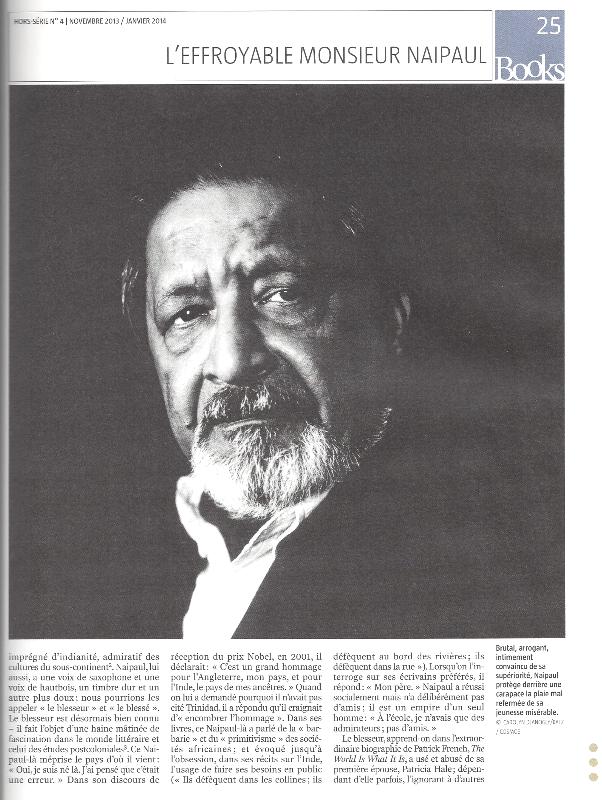

Tàn nhẫn, xấc xược, cực kỳ trịch thượng, giấu kín vết thương không thể nào lành, là 1 tuổi thơ khốn khổ của mình

Cái sự lưu vong của ông ta

thì đếch làm sao chịu nổi

Tờ Books,

Avril 2013, có 1 bài phạng Zweig

tơi bời xí oắt, và tự hỏi, hà cớ làm sao 1 mà ông văn chương dở như

hạch, lại

được ca thấu trời.

ZWEIG, CE PEPSI

DE LA LITTERATURE

A quoi est

due l'immense popularité dont continue de jouir Stefan Zweig? A une

sorte de talent

hollywoodien fait pour plaire à la bourgeoisie inculte. Les Mann, Musil

et

autres Canetti ne s'y trompaient pas, qui le couvraient de leur mépris.

Un poète

anglais d' origine allemande enfonce le clou dans cet article d'une

rare méchanceté

qui fracasse aussi la statue morale de l'humaniste.

MICHAEL

HOFMANN. London Review of Books.

His Exile

Was Intolerable

Anka

Muhlstein

May 8, 2014

Issue The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World

by George

Prochnik

Other Press,

390 pp., $27.95

The Grand

Budapest Hotel

a film

directed by Wes Anderson

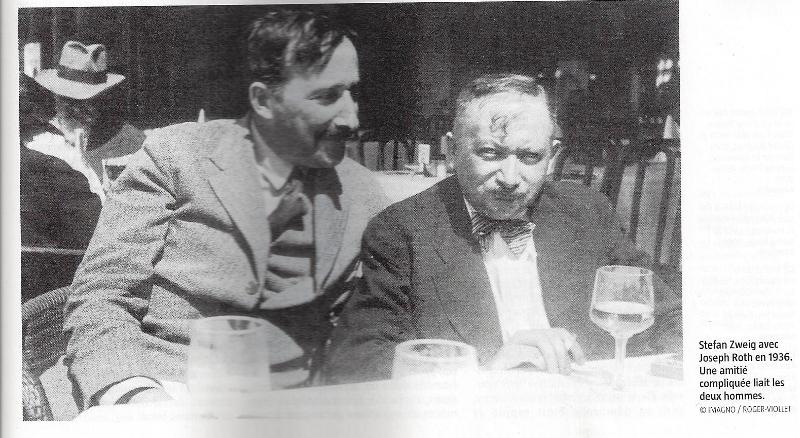

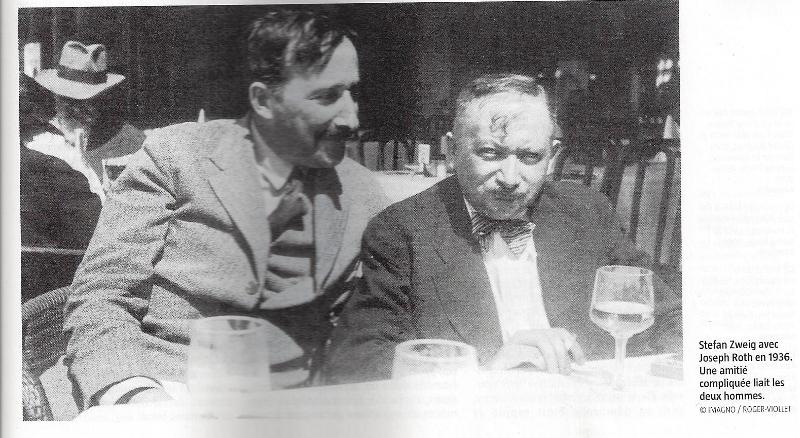

Imagno/Hulton

Archive/Getty Images

Stefan Zweig

and Joseph Roth, Ostende, Belgium, 1936

On February

23, 1942, Stefan Zweig and his young wife committed suicide together in

Petrópolis, Brazil. The following day, the Brazilian government held a

state

funeral, attended by President Getulio Vargas. The news spread rapidly

around

the world, and the couple’s deaths were reported on the front page of

The New

York Times. Zweig had been one of the most renowned authors of his

time, and

his work had been translated into almost fifty languages. In the eyes

of one of

his friends, the novelist Irmgard Keun, “he belonged to those that

suffered but

who would not and could not hate. And he was one of those noble Jewish

types

who, thinskinned and open to harm, lives in an immaculate glass world

of the

spirit and lacks the capacity themselves to do harm.”1

The suicide

set off a surge of emotion and a variety of reactions. Thomas Mann, the

unquestioned leader of German-language writers in exile, made no secret

of his

indignation at what he considered an act of cowardice. In a telegram to

the New

York daily PM, he certainly paid tribute to his fellow writer’s talent,

but he

underscored the “painful breach torn in the ranks of European literary

emigrants by so regrettable a weakness.” He made his point even clearer

in a

letter to a writer friend: “He should never have granted the Nazis this

triumph, and had he had a more powerful hatred and contempt for them,

he would

never have done it.” Why had Zweig been unable to rebuild his life? It

wasn’t

for lack of means, as Mann pointed out to his daughter Erika.

This is the

subject of Georges Prochnik’s The Impossible Exile, a gripping,

unusually

subtle, poignant, and honest study. Prochnik attempts, on the basis of

an

uncompromising investigation, to clarify the motives that might have

driven to

suicide an author who still enjoyed a rare popularity, an author who

had just

completed two major works, his memoir, The World of Yesterday, and

Brazil: Land

of the Future. He had also finished one of his most startling novellas,

Chess

Story, in which he finally addressed the horrors of his own time,

proving that

his creative verve hadn’t been in the least undermined by his ordeals.

Recently

he had married a loving woman, nearly thirty years his junior. And he

had

chosen of his own free will to leave the United States and take refuge

in

Brazil, a hospitable nation that had fired his imagination.

Why had

exile proved so intolerable to Stefan Zweig when other artists drew a

new vigor

and inspiration from it? Prochnik notes that Claude Levi-Strauss,

walking New

York’s streets for the first time in 1941, described the city as a

place where

anything seemed possible…. What made [its charm], he wrote, was the way

the

city was at once “charged with the stale odors of Central Europe”—the

residue

of a world that was already finished—and injected with the new American

dynamism.

Zweig never

experienced moments of terror or the life-and-death decisions to be

made in the

course of a few hours, nor was he forced to slog through the long and

challenging reconstruction of a professional career. He always seemed

to get

out well before the wave broke, with plenty of time to pack his bags,

sort

through his possessions, and, most important of all, pick his

destination. He

left Austria and his beautiful home in Salzburg as early as 1933. A

police

search on the false pretext of unearthing a cache of illegal weapons

led him to

depart for Great Britain, leaving his wife, Friderike, and his two

stepdaughters behind. Unlike his German colleagues, including Thomas

Mann, who

had left Germany upon Hitler’s rise to power in January 1933 with no

hope of

returning home until there was a change of regime, Zweig was able to

travel

freely between London, Vienna, and Salzburg for another five years. An

Austrian

passport, valid until the Anschluss in March 1938, allowed him to make

trips to

the United States and South America.

But Hitler’s

rise to power had serious and immediate consequences for Zweig, in

particular

the loss of his German publisher, Insel Verlag. Still, at the start of

the Nazi

era, Zweig’s books continued to be available in Germany. Even though it

was

forbidden to display them or allude to them in the press, his sales

figures

remained virtually unchanged in 1933 and 1934. More surprising still,

Richard

Strauss—who had asked Zweig to write the libretto of his opera The

Silent

Woman—fought against the suppression of Zweig’s name on the program of

the

work, at a time when mentioning Jewish artists was prohibited. The

opera had

its premiere in June 1935, but only two performances followed. Strauss

was

nevertheless very anxious to continue working with Zweig. He even

suggested

they keep the collaboration secret until better times, but Zweig’s

sense of

solidarity with his fellow Jewish artists forbade him to accept.

Those first

years of what we can call a comfortable exile were punctuated not by

drama—because Zweig was a master at the art of avoiding drama in his

personal

life—but by a number of conjugal adjustments. Stefan and his wife were

on very

good terms, and he’d asked her to hire him a secretary when he moved to

London.

She selected a German refugee, Lotte Altman, a serious young woman,

delicate

and discreet, who suited Zweig perfectly. Lotte traveled with him

frequently,

and went with him to meet Friderike in Nice, before he was to take the

ship for

New York.

The stay in

Nice was proceeding harmoniously, at least until Zweig asked Friderike

to stop

by the British consulate to iron out a problem. When she got to the

consulate,

she realized that she’d forgotten an important document and went back

to the

hotel to retrieve it. She walked into the room and found Stefan and

Lotte fast

asleep. They had a rude awakening but Friderike kept her sang-froid,

found the

document, and headed back to the consulate; upon her return, however,

she

demanded not that Lotte be fired, but that she immediately take some

time off.

A few days later, Zweig boarded his ship. Friderike accompanied him to

his

stateroom. A letter was waiting for him on the dresser. Both of them

recognized

Lotte’s handwriting, and Zweig made the surprising gesture of handing

it to

Friderike without opening it. The entire incident strikes me as

indicative of

his gift for evasiveness and his loathing of conflict.

Zweig

arrived in New York in January 1935: he was fifty-four years old and at

the

height of his career. He wasn’t a novelist of Thomas Mann’s caliber,

and he

knew that. He was sufficiently self-effacing to take pride in the fact

that the

Nazis had burned his books along with those of Freud, Einstein, and the

brothers Mann. But his sales beat all records. “Shortening and

lightening seem

to me a boon to the work of art,” he had written to Richard Strauss and

quite

naturally he chose as his favorite literary form the novella, a quick

and

concentrated format that lent itself to splashy, racy subjects; it won

him

plenty of readers who were tired of “nineteenth-century

triple-deckers.” His

biographies, which smacked more of novelized history than exhaustive

scholarship, sold well for the same reasons. He’d recently published

his

biography of Erasmus, which he considered a veiled self-portrait:

Erasmus, the

humanist, represented his own values while his antagonist, Martin

Luther, was

emblematic of the man of action.

The book was

an immediate success, even in Germany. His reputation, his self-imposed

exile,

his friendship with Joseph Roth and other artists destroyed by

political

developments, his network of contacts with refugees in Switzerland,

Great

Britain, and France, all prompted the intense curiosity of journalists.

Everyone wanted to hear him condemn the Nazi regime. A press conference

was

held in the offices of his publisher, Viking. But in response to the

precise

and pointed questions from reporters who wanted to know what he thought

of

Hitler, what was going on in Germany, the state of mind among the

German

populace and the refugees, Zweig was evasive, regarding the press with

“his

typical ‘languid composure’” and concluding with the statement, “I

would never

speak against Germany. I would never speak against any country.”

Prochnik,

well aware that the biographer’s job is not to judge but rather to try

to

understand, instead of taking a simplistic approach and condemning

Zweig’s

passive stance, chooses to view it as a manifestation of his hope that

the

German people might still come to their senses—perhaps influenced by

the fact

that his books were still selling so strongly in Germany. Thus “the

best

response to Hitler’s election was not to demonize his supporters, Zweig

believed, but to communicate to them the value of the rich German

cultural

legacy that was being jeopardized by Nazi politics.” Zweig envisioned

the

publication of a monthly literary review that would feature articles in

different languages, so as

to cement,

by its high ethical and literary standards, an aristocratic European

brotherhood that eventually would be able to counteract the demagogic

propaganda unleashed by those forces that were trying to bring about

the moral

destruction of Europe.

Nothing came

of the project and a disappointed Zweig returned to Great Britain,

convinced

that he’d lost all real influence. He felt certain that it was

impossible to

beat the Nazis on their own terms, and he chose to believe that his

silence

would be taken as condemnation. That was an attitude far too subtle and

circumspect to be grasped by political refugees and the American public.

His refusal

to come out openly against Hitler weighed even more heavily as Thomas

Mann

became more and more politically active. When the University of Bonn

revoked

Mann’s honorary degree, in 1936, he wrote an emphatic diatribe,

underscoring

his “immeasurable revulsion against the wretched events at home.” It

was read

in Germany in the form of a clandestine pamphlet, attaining a

circulation of

20,000 copies, after which it was translated and distributed in the

United

States and worldwide. Mann thus became the unrivaled spokesman for all

artists

in exile, as acknowledged by Toscanini, who praised the text as

“magnifico,

commovente, profondo, umano.”

Nonetheless,

Zweig remained silent: “One would like to crawl into a mouse-hole…. I

am a man

who prizes nothing more highly than peace and quiet.” He took advantage

of the

next two years of respite—Austria remained an independent democracy

until

1938—to sell his house in Salzburg and especially his extraordinary

collection

of manuscripts, keeping only a few particularly choice rarities and

Beethoven’s

desk. He also put an end to his marriage, while successfully remaining

good

friends with Friderike. He seemed to be girding himself to deal calmly

with an

enormous upheaval:

Our

generation has gradually learned the great art of living without

security. We

are prepared for anything…. There is a mysterious pleasure in retaining

one’s

reason and spiritual independence particularly in a period where

confusion and

madness are rampant.

But he was

deceiving himself.

Fox

Searchlight Pictures

Ralph

Fiennes in The Grand Budapest Hotel

Things

changed radically on September 3, 1939, when, in the aftermath of the

invasion

of Poland, Great Britain declared war on Germany. From one day to the

next,

Zweig became an enemy alien in the eyes of Great Britain.

Psychologically, it

came as a rude shock. “I believe that the new Ministry for Information

should be

informed a little at least about German Literature and know that I am

not an

‘enemy alien’ but perhaps the man who (with Thomas Mann) could be more

useful

than any others,” he wrote to his publisher.

Of course,

the British weren’t about to take the ridiculous step of putting a

renowned

author in an internment camp, but Zweig was forced to go through the

extensive

process of requesting identity papers, and while waiting for them was

forbidden

to travel more than five miles from his place of residence unless

specifically

authorized, which in turn required hours of his time and lengthy

discussions

with functionaries who’d never heard of him. His exasperation was bound

up with

his despair at finding himself deprived of his native language. Not

only was it

now impossible for him to publish anything in Germany, refugees were

strongly

advised against speaking German in public. “[Our] language…has been

taken away

from us, [and we are] living in a country…in which we are only

tolerated.” In

his journal he wrote, “I am so imprisoned in a language, which I cannot

use.”

In spite of

his indignation, he did everything necessary to apply to be a

naturalized

subject, and completed the process in March 1940, for himself and for

Lotte,

whom he’d married a few months earlier. At the same time, he purchased

a number

of US Savings Bonds and asked his American publisher, Ben Huebsch, to

hold onto

them for him. Events continued to rush headlong. The fall of France

shook him

up. The threat of an invasion of England terrified him. Finally,

faithful to

his habit of seeking exile in advance, he left for New York with Lotte

in July

1940.

It was a

changed man who set foot in America. Disheartened, embittered, and

irritated by

New York’s luxury, magnificence, and glamour, disgusted by his own

aging to the

point that he tried a rejuvenating cure of hormone injections that left

him

just as weary and upset as before, he was miserable. The only bright

spot in

this period was the arrival of Friderike, for whom he had obtained one

of the

special visas that had been set aside for a thousand or so endangered

intellectuals.

One way to

understand Zweig is in contrast to Thomas Mann, who came to the United

States

around the same time, forcefully declaring that he represented the best

of

Germany: “Where I am, there is Germany…. I carry my German culture

within me. I

have contact with the world and I do not consider myself fallen.” Zweig

lacked

such self-confidence, and bemoaned the fact that “emigration implies a

shifting

of one’s center of gravity.” The chief difference between the two men

was that

Mann was a member of the German high bourgeoisie, with roots sinking

many

generations deep in his country’s past, while Zweig, a Jew who rejected

Zionism, appreciated above all else “the value of absolute freedom to

choose

among nations, to feel oneself a guest everywhere.”

Prochnik,

who is well aware of the painful shift in self-perception that can

afflict

those in exile, clearly shows how the elegant Viennese

author—acclaimed, free

to go wherever he liked, so unobservant a Jew that his mother wrongly

suspected

him of having converted, who had been married to a Catholic2—despaired

when he

found himself suddenly plunged into the ranks of the wandering Jews.

“His sense

of being forced to identify with people who bore no relation with him

had come

to seem—along with nomadism—the defining experience of exile.”

Zweig

suffered all the more because, in spite of his pleasant life as a rich

and

assimilated Jew, he was always aware of how precarious matters could be

for his

coreligionists. Here Prochnik recounts a significant anecdote:

One day in

the 1920s when Zweig happened to be traveling in Germany with [the

playwright]

Otto Zarek, the two men stopped off to visit an exhibition of antique

furniture

at a museum in Munich…. Zweig stopped short before a display of

enormous

medieval wooden chests.

“Can you

tell me,” he abruptly asked, “which of these chests belonged to Jews?”

Zarek

stared uncertainly—they all looked of equally high quality and bore no

apparent

marks of ownership.

Zweig

smiled. “Do you see these two here? They are mounted on wheels. They

belonged

to Jews. In those days—as indeed always!—the Jewish people were never

sure when

the whistle would blow, when the rattles of pogrom would creak. They

had to be

ready to flee at a moment’s notice.”

We have the

impression that he was suddenly gripped by an ancestral fear and that

the

nightmare embedded deep in his subconscious had suddenly become real.

Another

change came in his attitude toward those who came to him for help. He’d

always

shown an easy generosity in the past, but the supplicants multiplied in

number

and he realized he was unable to keep up: “[I am] the victim of an

avalanche of

refugees…. And how to help these writers who even in their own country

were

only small fry?”

Still

paralyzed by his stubborn refusal to take a clear political position,

he

couldn’t follow the example set by Mann, equally beset by those in

search of

help, and support the aid organizations. Asked to deliver a ten-minute

talk at

a fund-raiser for the Emergency Rescue Committee, he spent hours

perfecting an

anodyne speech: “I do not want to say a word that could be interpreted

as

encouragement for America’s entry into the war, no word that announces

victory,

nothing that justifies or glorifies war, and yet the thing must have an

optimistic ring.”

The only

solution he could find was to plunge headlong into his work. He left

New York

and took refuge in Ossining where he’d be able to finish his

autobiography, now

that he was done with his book about Brazil. That town was an odd

choice,

devoid of all charm and interest, lying in the shadow of Sing Sing

prison, but

still it was justified by the presence there of Friderike, an

indispensable

assistant in checking certain details of his text. He worked feverishly

and, at

the end of the summer of 1941, exhausted, yearning for a life that

might afford

him a certain degree of stability, he decided to go back to Brazil,

which had

offered him a permanent residence permit.

This

decision failed to bring him the calm that he expected. Though his book

on

Brazil had acceptable sales, it was not given a favorable reception by

Brazilian critics annoyed at Zweig’s vision of an exotic and

picturesque

paradise. Still in search of more tranquility, he left Rio for the

small town

of Petrópolis where, as he wrote to Friderike, “One lives here nearer

to

oneself and in the heart of nature, one hears nothing of politics…. We

cannot

pay our whole life long for the stupidities of politics, which have

never given

us a thing but only always taken.” Once again, he was deceiving himself.

On December

7, the Japanese attacked the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. The next

day, the

United States declared war. Zweig was once again seized by a wave of

irrational

panic. He feared a German invasion of South America. Every possible way

out

seemed to be sealed off, one after the other. He despaired at being

“miles and

miles away from all that was formerly my life, books, concerts, friends

and

conversation.” But there was one constant in Zweig’s life, the urge to

write.

He set to work on his last novella, Chess Story, and for the first time

he

brought Nazis in action into the plot. In his story, an Austrian lawyer

is

arrested in Vienna. The Gestapo subjects him to an intolerable form of

mental

torture. The man is confined to a hotel room, cut off from all human

interaction, deprived of books, pen, paper, and cigarettes, and

sentenced to

spend weeks staring at four bare walls: “There was nothing to do,

nothing to

hear, nothing to see, nothingness was everywhere…a completely

dimensionless and

timeless void.” He finished writing on February 22. The next day, he

and Lotte

drank a fatal dose of Veronal.

The photo

taken by the police shows him stretched out on his back, his hands

crossed;

she’s lying beside him, her head on his shoulder, one hand on his.

Prochnik

concludes: “He looks dead. She looks in love.”

“Mort à

jamais?” (Dead forever?) asks Proust’s narrator when the writer

Bergotte dies.

To Proust, an artist could never die if his works outlive him. In 1942,

Zweig

certainly looked dead. No one read his books anymore. But he was only

in

purgatory. His books were rapidly reissued after the end of the war, in

Austria, Germany, Italy, and France—the most popular title being The

World of

Yesterday—and later in Great Britain and the United States. More

recently,

thanks to New York Review Books and Pushkin Press, a substantial

portion of his

oeuvre has been republished in new translations, and there is clearly a

Zweig

revival underway.

Even more

surprising, the revival extends to the movies. In his newest film, The

Grand

Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson takes his inspiration not from a specific

novella

but from the entire body of Zweig’s work and his life. The film is set

in the

imaginary republic of Zubrowka (the irresistibly droll name is

evocative of a

Polish bison grass–scented vodka) and tells of the difficulties faced

by

Monsieur Gustave, the concierge of the Grand Budapest Hotel. The

film—zany,

fast-moving, punctuated by a chase scene with a villain on skis pursued

by a

duo riding a luge, a prison escape involving tiny metal files concealed

in

pastries, an elderly countess’s idyll with the concierge, a murder, and

a

venomous heir—would simply echo the madcap comedies of the 1930s if

Anderson

hadn’t so deftly given his story a background set in a Europe where any

sense

of security is rapidly slipping away. That is where the film’s debt to

Zweig

lies.

Of all the

characters in the film, it is unexpectedly the concierge—played by

Ralph

Fiennes in rare form, with a trim little paintbrush mustache, shifty

eyes and a

supple grace to his movements, comfortable mastery of all languages, a

certain

latitude in his sexual tastes, and an overall sense of calm broken here

and

there by glimmers of disquiet—who best evokes Zweig. And precisely like

Zweig,

who could reach out at any time to his friends, relations, and

publishers

around the world, Monsieur Gustave, a member of the all-powerful

society of

hotel concierges, can draw upon a network of infallible efficiency.

But all

these contacts prove useless in the face of an increasingly brutal

political

reality. In his memoirs, Zweig laments the end of a world where you

could

travel without passports, without being called upon to justify your

existence,

and in the film it is the arrival of the border guards that spells the

doom of

the fictional concierge. The first time they appear, he’s saved by the

intervention of an officer who recognizes in him an indulgent witness

of his

childhood holidays, but the second time he falls victim to the

gratuitous

violence of the henchmen of a terrifying power. It’s Zweig’s influence

that

tinges the film with nostalgia and gives it its depth.

—Translated

from the French by Antony Shugaar

1 Quoted by

Leon Botstein in “Stefan Zweig and the Illusion of the Jewish

European,” Jewish

Social Studies, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Winter 1982). ↩

2 Friderike

Zweig, née Burger, had a Jewish father but converted at a young age. ↩

1

Quoted by

Leon Botstein in “Stefan Zweig and the Illusion of the Jewish

European,” Jewish

Social Studies, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Winter 1982). ↩

2

Friderike

Zweig, née Burger, had a Jewish father but converted at a young age. ↩

Comments

Post a Comment