W.S. Merwin Tribute

- Khanh Huynh Tít sốc như thế , thân hữu mới chịu đọc bác ạ.

- Quoc Tru Nguyen Yes, I Think So. Tks

Khanh Huynh shared a post.

Cảm ơn bác Quoc Tru Nguyen cho share.

Ngàn năm trăng hỏi tuổi ?

Ngàn năm trăng hỏi tuổi ?

Quoc Tru Nguyen

Thư gửi Su Tung-po

Cả ngàn năm sau

Tớ hỏi hoài hỏi hoài

Cũng vẫn những câu hỏi

Ngài đã từng ưu tư, trăn trở

Chẳng có gì thay đổi

Ngoại trừ cái âm thanh, giọng điệu…

Cái cái tiếng vang, hay, tiếng dội

Cứ sâu lắng mãi ra

Và điều mà Ngài viết, về "bàn chân ai rất nhẹ, tựa hồn những năm xưa"

Hay, cái chuyện tới lui của tuổi đời, của thời đại….

Trước khi Ngài trở nên già khòm

Tớ chẳng biết gì hơn Ngài, về cái điều Ngài hỏi

Khi, đêm đen, ngồi trên một thung lũng

Nghĩ tới Ngài, ngồi trên sông

Và một mảnh trăng

Trong giấc mơ của những con chim nước

Và tớ nghe ra sự im lặng sau những câu hỏi của Ngài

Chúng bao nhiêu tuổi rồi nhỉ, vào 1 đêm

Như đêm nay?

A Letter to Su Tung-p'o

Almost a thousand years later

I am asking the same questions

you did the ones you kept finding

yourself returning to as though

nothing had changed except the tone

of their echo growing deeper

and what you knew of the coming

of age before you had grown old

I do not know any more now

than you did then about what you

were asking as I sit at night

above the hushed valley thinking

of you on your river that one

bright sheet of moonlight in the dream

of the waterbirds and I hear

the silence after your questions

how old are the questions tonight

W.S. Merwin

The Essential W.S. Merwin

Thư gửi Su Tung-po

Cả ngàn năm sau

Tớ hỏi hoài hỏi hoài

Cũng vẫn những câu hỏi

Ngài đã từng ưu tư, trăn trở

Chẳng có gì thay đổi

Ngoại trừ cái âm thanh, giọng điệu…

Cái cái tiếng vang, hay, tiếng dội

Cứ sâu lắng mãi ra

Và điều mà Ngài viết, về "bàn chân ai rất nhẹ, tựa hồn những năm xưa"

Hay, cái chuyện tới lui của tuổi đời, của thời đại….

Trước khi Ngài trở nên già khòm

Tớ chẳng biết gì hơn Ngài, về cái điều Ngài hỏi

Khi, đêm đen, ngồi trên một thung lũng

Nghĩ tới Ngài, ngồi trên sông

Và một mảnh trăng

Trong giấc mơ của những con chim nước

Và tớ nghe ra sự im lặng sau những câu hỏi của Ngài

Chúng bao nhiêu tuổi rồi nhỉ, vào 1 đêm

Như đêm nay?

A Letter to Su Tung-p'o

Almost a thousand years later

I am asking the same questions

you did the ones you kept finding

yourself returning to as though

nothing had changed except the tone

of their echo growing deeper

and what you knew of the coming

of age before you had grown old

I do not know any more now

than you did then about what you

were asking as I sit at night

above the hushed valley thinking

of you on your river that one

bright sheet of moonlight in the dream

of the waterbirds and I hear

the silence after your questions

how old are the questions tonight

W.S. Merwin

The Essential W.S. Merwin

When You Go Away

When you go away the wind clicks around to the north

The painters work all day but at sundown the paint falls

Showing the black walls

The clock goes back to striking the same hour

That has no place in the years

And at night wrapped in the bed of ashes

In one breath I wake

It is the time when the beards of the dead get their growth

I remember that I am falling

That I am the reason

And that my words are the garment of what I shall never be

Like the tucked sleeve of a one-armed boy

Khi Gấu Đi Xa

Gió quần quần về phía Bắc

Mấy tay thợ sơn tường hì hục suốt ngày

Và khi đêm xuống

Nước sơn trôi tuột

Phô ra những bức tường đen thui

Chuông đồng hồ gõ hoài, gõ hoài,

Cũng 1 thời gian

Chẳng có nơi chốn nào

Trong những năm năm tháng tháng

Và đêm tới

Cuộn mình trên giường của những tro than, điêu tàn

Trong 1 hơi thở, tớ thức giấc

Đó là thời gian

Râu người chết cứ thế mọc dài mãi ra

Tớ nhớ là trong khi tớ té

Tớ là lý do

Của những từ ngữ

Chúng là quần áo của điều mà tớ chẳng bao giờ sẽ là

Như cánh tay áo

Của 1 thằng bé cụt tay

Rain at Night

This is what I have heard

at last the wind in December

lashing the old trees with rain

unseen rain racing along the tiles

under the moon

wind rising and falling

wind with many clouds

trees in the night wind

after an age of leaves and feathers

someone dead

thought of this mountain as money

and cut the trees

that were here in the wind

in the rain at night

it is hard to say it

but they cut the sacred 'ohias then

the sacred koas then

the sandalwood and the halas

holding aloft their green fires

and somebody dead turned cattle loose

among the stumps until killing time

but the trees have risen one more time

and the night wind makes them sound

like the sea that is yet unknown

the black clouds race over the moon

the rain is falling on the last place

Mưa Đêm

Đó là điều tớ nghe,

sau cùng, gió Tháng Chạp

quất túi bụi lên mấy thân già

với mưa

một thứ mưa mù loà - đếch nhìn thấy, đúng hơn, unseen –

chạy dài theo mái ngói

dưới trăng

gió trồi lên, trụt xuống

gió với rất nhiều mây

cây trong gió đêm

sau một thế hệ lá và lông

một người nào đó ngỏm

tưởng ngọn núi này là tiền bạc

và cắt cây

những cây ở đây

trong gió

trong mưa đêm

thật khó nói điều đó

nhưng họ cắt “ohias” thiêng

rồi “koa” thiêng

rồi dép cây, guốc gỗ

rồi halas

cầm lơ lửng những ngọn lửa xanh

và một người nào đó chết, để bầy gia súc chạy rông

giữa những gốc cây cho tới thời giết người

nhưng cây, lại một lần nữa sống lại

và gió đêm làm chúng kêu thành tiếng

như biển

tuy chưa được biết tới

mây đen chạy ùa lên mặt trăng

mưa rơi trên nơi chốn sau cùng.

Place

On the last day of the world

I would want to plant a tree

what for

not for the fruit

the tree that bears the fruit

is not the one that was planted

I want the tree that stands

in the earth for the first time

with the sun already

going down

and the water

touching its roots

in the earth full of the dead

and the clouds passing

one by one

over its leaves

Nơi chốn

Vào cái ngày cuối cùng của tên Gấu Cà Chớn

Nó bèn thèm trồng 1 cái cây

Không phải cho trái

Cây cho trái

Không phải cây được trồng

Thằng khốn muốn thứ cây

Đứng 1 phát, lần đầu tiên, ở trên mặt đất

Với 1 ông mặt trời, đã lặn

Và nước mò tới rễ

Bèn sờ soạng

Trên trái đất đầy người chết

Và mây bay qua

Từng cụm, từng cụm

Bên trên lá của nó

The Essential W.S. Merwin

Kỷ niệm ngày đi xa của tớ

Năm nào thì cũng rứa

Ta trải qua ngày tớ đi xa

Vậy mà cứ làm mặt lạ với nó!

Khi ánh lửa sau cùng giơ tay vẫy vẫy

Và im lặng thì tràn đầy

Kẻ lữ hành mỏi mệt

Y chang đốm sáng sau cùng, của 1 ngôi sao sắp tuyệt tích giang hồ

Nghĩa là, cạn ánh sáng - Cạn láng đời thì cũng “cẩm” như vậy -

Và tớ sẽ chẳng thấy mình

Áo quần lạ lẫm

Ngạc nhiên với đời

Và tình yêu của 1 phụ nữ

Và cái sự mặt dầy của lũ đực rựa

Và bữa nay, ngồi viết sau ba ngày mưa dầm

Nghe tiếng chim hồng tước hót

Và cái sự rơi rụng, ngưng

Và cúi đầu chẳng biết vì đâu, vì cái gì…

W. S. MERWIN

1927-

The following poem inspires us to reflect on what seldom crosses our minds. After all (literally after all), such an anniversary awaits every one of us.

Bài thơ sau đây gợi hứng cho chúng ta, về cái điều hiếm chạy qua đầu chúng ta.

Nói cho cùng, "kỷ niệm cái chết của tôi" đâu bỏ quên, bất cứ ai?

Czeslaw Milosz: The Book of Luminous Things

FOR THE ANNIVERSARY OF MY DEATH

Every year without knowing it I have passed the day

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam of a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

POUR L'ANNIVERSAIRE DE MA MORT

Chaque année sans le savoir je passe la journée

Quand les derniers feux vont me faire signe

Et le silence s'établira

Voyageur infatigable

Comme le rayon d'une étoile sans lumière

Alors je ne ferai plus

Me trouver dans la vie comme dans un vêtement étrange

Surpris à la terre

Et l'amour d'une femme

Et l'impudeur des hommes

Comme écrit aujourd'hui après trois jours de pluie

Entendre le troglodyte chanter et la chute cesser

Et s'incliner sans savoir à quoi

Bài thơ này, tương tự bài văn tế Gấu Đực, của Gấu Cái. Thảo Trường, khi chưa đi xa, đọc, gật gù, được quá đi chứ:

Văn tế nhà văn Nguyễn Quốc Trụ

Em năn nỉ để em đi trước ,

Để được anh lo lắng chăm sóc một lần.

Lần đầu mà cũng là lần cuối.

Vậy mà anh vẫn từ chối.

Vậy mà anh vẫn muốn chiếm thượng phong,

Anh nằm xuống,

Mặc cho nhà quàn vẽ rắn vẽ rồng,

Má đỏ môi hồng

Cà vạt veston,

Giày tây bóng láng như đồng,

Những thứ mà trên đời anh chúa ghét

Quan tài thì phủ đầy hoa,

Hoa hồng hoa đỏ hoa xanh, và

Con cháu anh- Đứa khóc ông- đứa khóc cha!

Còn em, làm văn tế khóc chồng.

Ối ! Trụ ơí! Bốn mươi năm chung sống.

Hai mươi năm lưu lạc xứ người,

Em đi làm- anh ở nhà viết văn đọc sách.

Ra đường – em lái xe- anh lười seatbelt-

Nên ngồi băng sau làm ông chủ,

Còn hai mươi năm kia..

Hết mười năm anh ở trong tù,

Em nuôi mẹ nuôi con,

Mười năm đầu từ khi cưới nhau

Cô phù dâu theo anh về trong giấc chiêm bao !!

Em đi dạy học- anh làm công chức,

Sáng anh ngồi quán Cái Chùa.

Cà phê sữa croissant

Trưa lang thang đại lộ Hàm Nghi - Cầu Calmette

Tối thì Văn Cảnh- Đêm Mầu Hồng.

Không ai kèn cựa với người đã chết.

Mà em muốn nhắc để cám ơn anh.

Đã rèn luyện em trong cay đắng của đời.

Và đã thương yêu em như một Bà Trời.

“Em ơi anh không biết làm thơ tình,

Nên đành mượn hai câu thơ của Bùi Giáng để tặng em

Anh thương em như một Bà Trời

Còn em thương anh như một Ông Trời Bơ Vơ”

Ôi Trụ ơi,

Vô thọ tướng-vô nhân tướng-vô thọ giả tướng

Vô chúng sanh tướng. Vạn vật giai không

Cát bụi thì xin trở về nơi cát bụi.

Hiền thê biệt bút

Thảo Trần

Năm nào thì cũng rứa

Ta trải qua ngày tớ đi xa

Vậy mà cứ làm mặt lạ với nó!

Khi ánh lửa sau cùng giơ tay vẫy vẫy

Và im lặng thì tràn đầy

Kẻ lữ hành mỏi mệt

Y chang đốm sáng sau cùng, của 1 ngôi sao sắp tuyệt tích giang hồ

Nghĩa là, cạn ánh sáng - Cạn láng đời thì cũng “cẩm” như vậy -

Và tớ sẽ chẳng thấy mình

Áo quần lạ lẫm

Ngạc nhiên với đời

Và tình yêu của 1 phụ nữ

Và cái sự mặt dầy của lũ đực rựa

Và bữa nay, ngồi viết sau ba ngày mưa dầm

Nghe tiếng chim hồng tước hót

Và cái sự rơi rụng, ngưng

Và cúi đầu chẳng biết vì đâu, vì cái gì…

W. S. MERWIN

1927-

The following poem inspires us to reflect on what seldom crosses our minds. After all (literally after all), such an anniversary awaits every one of us.

Bài thơ sau đây gợi hứng cho chúng ta, về cái điều hiếm chạy qua đầu chúng ta.

Nói cho cùng, "kỷ niệm cái chết của tôi" đâu bỏ quên, bất cứ ai?

Czeslaw Milosz: The Book of Luminous Things

FOR THE ANNIVERSARY OF MY DEATH

Every year without knowing it I have passed the day

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam of a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

POUR L'ANNIVERSAIRE DE MA MORT

Chaque année sans le savoir je passe la journée

Quand les derniers feux vont me faire signe

Et le silence s'établira

Voyageur infatigable

Comme le rayon d'une étoile sans lumière

Alors je ne ferai plus

Me trouver dans la vie comme dans un vêtement étrange

Surpris à la terre

Et l'amour d'une femme

Et l'impudeur des hommes

Comme écrit aujourd'hui après trois jours de pluie

Entendre le troglodyte chanter et la chute cesser

Et s'incliner sans savoir à quoi

Bài thơ này, tương tự bài văn tế Gấu Đực, của Gấu Cái. Thảo Trường, khi chưa đi xa, đọc, gật gù, được quá đi chứ:

Văn tế nhà văn Nguyễn Quốc Trụ

Em năn nỉ để em đi trước ,

Để được anh lo lắng chăm sóc một lần.

Lần đầu mà cũng là lần cuối.

Vậy mà anh vẫn từ chối.

Vậy mà anh vẫn muốn chiếm thượng phong,

Anh nằm xuống,

Mặc cho nhà quàn vẽ rắn vẽ rồng,

Má đỏ môi hồng

Cà vạt veston,

Giày tây bóng láng như đồng,

Những thứ mà trên đời anh chúa ghét

Quan tài thì phủ đầy hoa,

Hoa hồng hoa đỏ hoa xanh, và

Con cháu anh- Đứa khóc ông- đứa khóc cha!

Còn em, làm văn tế khóc chồng.

Ối ! Trụ ơí! Bốn mươi năm chung sống.

Hai mươi năm lưu lạc xứ người,

Em đi làm- anh ở nhà viết văn đọc sách.

Ra đường – em lái xe- anh lười seatbelt-

Nên ngồi băng sau làm ông chủ,

Còn hai mươi năm kia..

Hết mười năm anh ở trong tù,

Em nuôi mẹ nuôi con,

Mười năm đầu từ khi cưới nhau

Cô phù dâu theo anh về trong giấc chiêm bao !!

Em đi dạy học- anh làm công chức,

Sáng anh ngồi quán Cái Chùa.

Cà phê sữa croissant

Trưa lang thang đại lộ Hàm Nghi - Cầu Calmette

Tối thì Văn Cảnh- Đêm Mầu Hồng.

Không ai kèn cựa với người đã chết.

Mà em muốn nhắc để cám ơn anh.

Đã rèn luyện em trong cay đắng của đời.

Và đã thương yêu em như một Bà Trời.

“Em ơi anh không biết làm thơ tình,

Nên đành mượn hai câu thơ của Bùi Giáng để tặng em

Anh thương em như một Bà Trời

Còn em thương anh như một Ông Trời Bơ Vơ”

Ôi Trụ ơi,

Vô thọ tướng-vô nhân tướng-vô thọ giả tướng

Vô chúng sanh tướng. Vạn vật giai không

Cát bụi thì xin trở về nơi cát bụi.

Hiền thê biệt bút

Thảo Trần

The

Final Prophecy of W. S. Merwin

By Dan Chiasson

March 17, 2019

The poems of Merwin’s mature career seemed to

have been delivered unto him, then transcribed by lightning flash.

Photograph

by Tom Sewell / NYT / Redux

Now we know the date. The

anniversary of W. S. Merwin’s death was, all along, March 15th. He’d

passed it ninety-one times and stopped on the ninety-second. But what did it

matter, really, which of the three hundred and sixty-five notches on the

roulette wheel would turn up as the winner? Here is “For the Anniversary of My

Death,” among Merwin’s most famous poems:

Every year without knowing it I have passed the

dayWhen the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam of a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

This little anticipatory poem has its way with time: it describes what Merwin imagines will have happened on March 15, 2019, but it is dedicated to, and reserved for, every March 15th thereafter. It’s a script for a commemorative ceremony, a eulogy banked years before its occasion. It also feels like a prank that Merwin played on us, the most chilling and ingenious trick that an American poet has played on his survivors since Walt Whitman challenged the rest of us to look for him, whenever we missed him, under our boot soles.

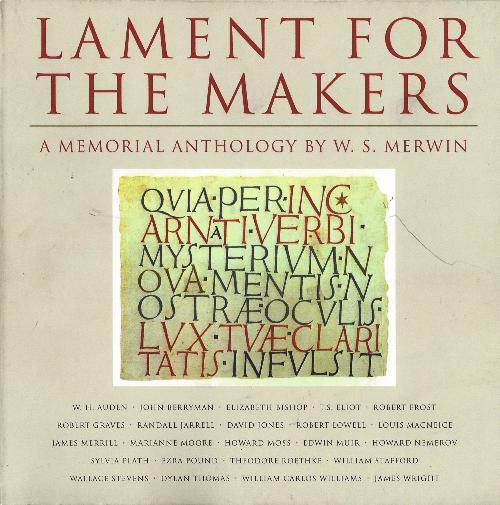

“For the Anniversary of My Death” is about the problem of being outlived. “Elegy,” Merwin’s great single-line poem—not the greatest short poem, but perhaps the shortest great poem, ever written—is about the converse problem, that of outliving. This is the poem in its entirety:

Who would I show it to

Poets write elegies, often, for other poets, but there is a paradox: the very figure whose sympathetic attention to their work allowed the work to flourish is now gone. An elegy can’t exist when its sponsor has become its subject. And yet the poem seems to answer, by a somewhat piqued rhetorical question, its subject’s request: Why haven’t you written my elegy?

Merwin was born in 1927, and grew up in Union City, New Jersey, and Scranton, Pennsylvania, where his father was a Presbyterian minister. The young Merwin composed hymns for his father’s church. A scholarship student at Princeton, he remembered working in the horse stables and apprenticing himself to R. P. Blackmur, the brilliant, gnomic critic, and to Blackmur’s friend, the poet John Berryman. His early poems were ominous, high-pitched, and starchy; when he broke with them, he broke for good. The poems of his mature career were often Delphic, haunted, and bleak. They seemed to have been delivered unto Merwin, who transcribed them by lightning flash: this effect of transcribed prophecy is achieved by their almost total lack of punctuation. This is how the jet stream must speak—or how a cleft in the bedrock might introduce itself. We have come very far from hardscrabble Pennsylvania or Merwin’s work-study job at Princeton. His several volumes of memoirs are extraordinarily warm, an interesting supplement to the stony verse. He lived, since the mid-seventies, on an abandoned pineapple plantation, in Hawaii, which he bought barren and turned, row upon row, into a lush forest of palm trees. Friends who have visited have come back changed.

Merwin published an excellent selected volume in 2017, which I reviewed in this magazine. I was finishing it up when I heard of the death of John Ashbery, who was born in the same year as Merwin. I remember thinking that Ashbery, in his bland, white high-rise in Chelsea, and Merwin, in his palm garden in Hawaii, were like the gates of the rising and the setting sun. American sentries: Ashbery faced east (his actual apartment faced slightly west; just go with it), and kept an eye on reality as it approached, always monitoring its fresh and new and bewildering presentations; Merwin looked west, and saw the moments as they bent toward obliteration, casting their long shadows backward. We’ll be in his shadow for some time yet.

W.

S. Merwin in The New Yorker

March 18, 2019

W. S. Merwin’s last poems in

The New Yorker are committed, above all, to the question of what lasts, and

how, in a world essentially characterized by impermanence.

Photograph by Tom Sewell / NYT / Redux

The former U.S. Poet

Laureate W. S. Merwin, who was known for his antiwar and ecological activism,

died on Friday in his home in Maui at the age of ninety-one. Between 1955 and

2014, Merwin published over two hundred works of poetry and prose in The New Yorker that

speak to the breadth and singularity of his monumental career.

Although Merwin’s earliest contributions to the

magazine, such as “Low

Fields and Light,” are of a mode that he would

later leave behind, they evince concerns that would drive his poetry for

decades: communion with the natural world, and with the lives and labor that it

sustains, but also that world’s erosion by time, modernity, and manufactured

violence. He had already begun to grapple with the poet’s position, his role

and responsibility as observer and scribe. The speaker of “The

‘Portland’ Going Out,” reflecting on his

proximity to a boating accident, notes, “In no time at all . . . / All of disaster

between us: a gulf / Beyond reckoning,” implicating himself in his distance

from the event.The early sixties saw Merwin begin to strip away punctuation and move toward a sparer, less straightforward, more opalescent style that hits its stride in such powerful, oracular poems as “The Wave,” “The Child,” and “The Asians Dying,” which would later compose “The Lice,” his 1967 collection written in response to the horrors of the Vietnam War. There is an arcane, fateful quality to this work; the author’s voice opens like a vessel for his entire era to echo through, even as it rings Biblical, apocryphal, as in “The Widow,” for example:

And you weep wishing you were numbers

You multiply you cannot be found

You grieve

Not that heaven does not exist but

That it exists without us

The poems of Merwin’s next book, “The Carrier of Ladders,” which would win him his first Pulitzer Prize, continued to experiment with breath and the line, fragments and run-ons. Engaging questions of memory and loss, as in “Edouard,” “The Old Room,” and “The Judgment of Paris,” they also further demonstrate his now-established poetics of conscience, of witness to indelible environmental and historical trauma. Poems like “The Free,” which ends, “and when we have gone they say we are with them forever,” negotiate the palpable presence of what has been effaced and destroyed and the failure—even hypocrisy—of any attempt to immortalize it.

The New Yorker also published a great deal of Merwin’s short prose—much of which troubles genre boundaries—starting with an uncanny, speculative 1969 piece titled “The Remembering Machines of Tomorrow,” which appears to anticipate the invention of smartphones. Merwin imagines “remembering machines” that “no longer retain mere symbols in an arbitrary system but something which can pass, at least, for whole experiences—intellectual, sensual, visionary, ” whose “development . . . will come to be regarded as an important next step in man’s evolutionary progress—something at once inevitable and worth anything it might cost. When the machines become small enough so that every person can have—then must have—his own, the day will be celebrated as the beginning of a new age of the Individual.” He continues:

The machines will retain, in flawless preservation (though the completeness of what they remember will occasion some dispute, for a time), not only what their owners experience but what their owners think they have experienced, and will sort out the one from the other. More and more, such distinctions will be left purely to the machines. And it will be noticed that the experience to be retained is itself becoming a dwindling fauna, clung to by sentimentalists, from afar, who still lay aside their machines for days at a time and secretly yearn for the imaginary liberties of the ages of forgetting.

Many of these works, such as “The Roofs” and “The Fountain,” read like parables or fairy tales, with some—such as “The Devil’s Pig,” “A Fable of the Buyers,” and “The Chart”—echoing the surreal, philosophical manner of Franz Kafka and Jorge Luis Borges. Merwin’s prose, whether closer to fiction or to memoir, is an oddly complementary contrast to his poetry and offers a trove of surprises, delights, and revelations. So, too, do his translations, which the magazine printed in the seventies, from the Russian, of Osip Mandelstam, and, from the Spanish, of Roberto Juarroz.

Well through the turn of the twenty-first century, Merwin continued to hone his poetic vision, which extended the tradition of American Transcendentalism. In 1994’s “Vixen”—which Matthea Harvey read on The New Yorker’s poetry podcast, in 2015—the delineations between poet, poem, and subject dissolve. “I have waked and slipped from the calendars / from the creeds of difference and the contradictions / that were my life and all the crumbing fabrications,” Merwin writes, imploring, “let my words find their own / places in the silence after the animals.” He won a second Pulitzer Prize for his 2008 collection, “The Shadow of Sirius,” which contains “The Nomad Flute,” “A Letter to Su T’ung Po,” and “A Single Autumn,” which James Richardson discussed on the poetry podcast, praising Merwin’s “need to live in a world where the simplest things had stories, where the stones in the garden were growing things for themselves.” “The Shadow of Sirius” also includes “Rain Light,” which portrays “the washed colors of the afterlife / that lived there long before you were born,” entreating us to “see how they wake without a question / even though the whole world is burning.” That final line provides the title of a documentary about Merwin and his cultivation of a palm-tree forest in Hawaii, which, along with his literary legacy, is protected by the Merwin Conservancy. In 2017, writing on “The Essential W. S. Merwin,” Dan Chiasson remarked that “his poems, like that forest, are a kind of time preserve. . . . Many of them will be around as long as the palms.”

Indeed, Merwin’s last poems in The New Yorker are committed, above all, to the question of what lasts, and how, in a world essentially characterized by impermanence. In “A Message to Po Chu-I,” the poet becomes the custodian of an ancient tradition but has no one to pass it along to. “I have been wanting to let you know / the goose is well he is here with me,” he writes, “but I have never known / where he would go after he leaves me.” In 2014’s “Living with the News,” whose title refers both to what “is not mentioned on the front pages / but somewhere far back near the real estate” and to “what the doctor comes to say,” the author asks, “Can I get used to it day after day,” confessing, “this is not the world that I remember.” Merwin’s final poem in the magazine, “The Blackboard,” relates a projection of his childhood, finding that “The question itself has not changed / but only the depths of memory / through which it rises.” Yet, in the end, he lets go, the stuff of the poem and the poet falling away, as if, at last, to rejoin the elements: “and where are they now the sins of omission / where is the cloud the schoolyard the dream / even now I am forgetting them.”

Henri Michaux

French

1899-1984

MY LIFE

You go off

without me, my life,

You roll,

And me, I'm still waiting to take the first step.

You take the battle somewhere else,

Deserting me.

You roll,

And me, I'm still waiting to take the first step.

You take the battle somewhere else,

Deserting me.

I've never

followed you.

I can't really make out anything in your offers.

The little I want, you never bring it.

I miss it; that's why I lay claim to so much.

To so many things, to infinity almost…

Because of that little bit that’s missing, that you never bring.

I can't really make out anything in your offers.

The little I want, you never bring it.

I miss it; that's why I lay claim to so much.

To so many things, to infinity almost…

Because of that little bit that’s missing, that you never bring.

1962

W.S. Merwin: Selected

Translations

Đời của Gấu

Mi đi hoang,

bỏ ta

Mi lăn vòng vòng

Còn ta, vưỡn đợi bước thứ nhất

Mi lâm trận ở đâu đó,

Bỏ chạy ta

Ta không bao

giờ theo miMi lăn vòng vòng

Còn ta, vưỡn đợi bước thứ nhất

Mi lâm trận ở đâu đó,

Bỏ chạy ta

Ta không làm sao xoay sở

Với những mời chào, dâng hiến của mi

Cái ta muốn, chỉ tí xíu, mi chẳng bao giờ đem tới

Ta nhớ nó; chính là vì thế mà ta cứ cằn nhằn hoài

Về đủ thứ, về thiên niên, vĩnh cửu….

Chính là cái cuộc bỏ lỡ đó, mi chẳng hề màng tới

When You Go Away: Remembering W. S. Merwin

By Kevin Young

W. S. Merwin’s work reversed itself, undoing

modernism almost step by step.

Photograph by Jill

Greenberg

When I think of W. S. Merwin, I think of oysters. Not his writing about them but his

eating them. I saw him do so in 2013, when I brought him to Emory as part of a

reading series I ran there. It was one of his last visits to the mainland from

his adopted home of Hawaii.

He did not so much give a reading as participate

in a conversation, onstage—on short risers, really—about his work and its

transformations. I was awed by him, and I remember less the specifics of what

he said than his demeanor, which was generous; he was somewhat frail but still

hearty. His work was nearly the opposite: it is at once sturdy and rhythmic,

steady in the best way, though it has a certain airiness about it, a clearing

haze.So, the oysters: after the event, a group of us took him to a lovely dinner in a back room of one of Atlanta’s terrific restaurants. When playing host, I often order for the table—at least the starters. Merwin ordered oysters, a dozen. When they came, he didn’t perform the false courtesy of offering one or making a show. It was clear that they were meant for him, and he sat and enjoyed them while others, around him, shared dishes (including oysters). It was the ordering, and sincere pleasure, of a man who knew what he liked and was purposeful in getting it. His poems could deal in ambiguities, but not his palate.

There was, in his work, many orders of pleasure, of course, and a rigor in its spokenness. His poems are also interested in certitude, or, better yet, finality. The experience of hearing him read “For the Anniversary of My Death,” as I had decades before, when he gave a reading at Stanford, stays with me. The poem remains a bravura performance, though not an ostentatious one; much like oysters, it is raw and briny and tender all at once—“and bowing not knowing to what.” There were other wonders that made their way into The New Yorker, where he published more than two hundred poems across seven decades. Like “Come Back,” from 1967: “You came back to us in a dream and we were not here / In a light dress laughing you ran down the slope / To the door / And knocked for a long time thinking it strange.” His work from that period feels almost shucked, for that’s what he’d done: thrown over and scraped clean the formal style that had won him the Yale Younger Poets Prize, in 1951. (Later he’d serve as a judge.) He was not alone among his generation—not even among his fellow Yale prize winners picked by W. H. Auden’s bold hand, like Adrienne Rich and James Wright—in turning from an earlier decorum to an openness, an immediacy, and, often, a politics that extended to form. Meter and punctuation were discarded, replaced by swift line breaks and urgent subjects, whether “The Herds” or “The Asians Dying.” Indeed, as in the work of other evolving poets, such as Amiri Baraka and June Jordan, form was exactly where politics took place, the line not so much a unit of breath as a way of breathlessly addressing a turbulent time.

Merwin’s book “The Lice,” from 1967, still seems absolutely brave in its willingness to invoke change as a necessary and human thing. This is a lesson we could stand to learn now; it might help us to make work of this urgent moment that endures. It is notable that some of his enduring work came from capturing and praising the seemingly ephemeral. Eventually, he would write about things that he came to consider eternal but that were somehow, now, in jeopardy: the whales, the rain forest, his beloved island home. He could find the forest in a leaf.

His “Looking for Mushrooms at Sunrise” enacts this attentive yet elusive praise:

Where they appear it seems I have been before

I recognize their haunts as though remembering

Another life

Where else am I walking even now

Looking for me

When Merwin came to Stanford, he was visiting Denise Levertov’s class, I recall, talking with us and looking over a few of our poems. You could add Levertov, whose teaching I admired, to the list of transformed and transformative artists of the sixties; her transformation, too, was simultaneously a change of form, which she wrote was “never more than a revelation of content.” Levertov had famously argued and ultimately broken with her longtime friend Robert Duncan about the uses of poetry in the midst of the Vietnam War. Her content and poetics had shifted, especially against the war, while Duncan expressed distaste for “empty and vain slogans,” claiming that “the poet’s role is not to oppose evil, but to imagine it.” They were, of course, both right. Merwin, starting in the late sixties, found a middle way that, for these two seemingly irreconcilable camps, would have otherwise seemed impossible, by crafting a lyric by turns outraged and interior. He essentially sang his way out.

He was generous as a reader, too, and I still remember, decades later, a poem of mine that he was kind to. Called “Casting,” the poem was about fishing with my father, and it wouldn’t appear in a book until fifteen years later, after myfather had died. He said kind things about the poem, and I think he rightly warned, about its short lines, that one must be wary or at least aware of the choppy rhythm that could result. It was good advice that I wouldn’t quite follow. His work already taught me that, too: one must write as one hears and not be afraid to capture an inner voice on the page, to own that song of self. This extended to hearing other voices, as in Merwin’s tremendous translations, which remind us of the connectedness of a self across language and time.

Merwin translated from the start—twenty years’ worth of his “Selected Translations” first appeared in 1969. In that book’s introduction, he wrote of his limitations, which, as he well knew, weren’t really anything of the sort. “The only languages outside English in which I have any proficiency at all are the romance languages, particularly French and Spanish. But I long ago forgot most of what Latin I ever learned, and more recently most of what Portuguese I ever knew; my reading Italian (which was all I had) was never anything but laborious and uncertain.” The translations were never laborious nor uncertain, perhaps because he understood that a translation had to become a new poem in English. And yet they never felt like Robert Lowell’s “Imitations,” in which the loose translations become just versions of Lowell’s poems.

When I set about writing the poems for what became my third book, “Jelly Roll: a blues,” which took from the sounds and spirit of that African and American art form, I was also reading a number of Spanish-language poets, including Federico García Lorca, whose work Merwin translated. Lorca’s love and use of flamenco before being killed by the fascists was inspiring—and no less than Ralph Ellison saw the connections between flamenco and blues. Merwin, in his translations, seemed to know the power of such connections. His take on Pablo Neruda’s “Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair” remains a totem for me. I realize how much of its power was hearing Neruda through Merwin and vice versa: he had a way of rendering work that also tenderized it, rather than producing the strange shoe leather or bruised fruit that some translations become from overhandling. “It is the hour of departure, the hard cold hour / which the night fastens to all the timetables.” That’s Neruda via Merwin. Romantic while keen-eyed.

Was Merwin the last of our romantics? His work reversed itself, undoing modernism almost step by step: from the formal, slightly surreal verse of mid-century, he time-travelled back to the unpunctuated experiments that marked high modernism; and then to a view of nature as noble and almost human, as in the work of the British romantics; and even to French epics late in life, inspired by his farmhouse in the South of France, which he owned for more than seventy years. His was, of course, the most postmodern of acts: to undo the mask and find not only a face but a form crafted to feel natural and expansive, even as it was conscious of artifice. As I recall, during that class at Stanford, someone asked him about images, and he passionately recited the story of the Japanese poet Kobayashi Issa and the death of his daughter, captured in a famous haiku. “The world is a world of dew. And yet, and yet.”

One of Merwin’s last poems in the magazine, “Living with the News,” feels especially benedictory:

Can I get used to it day after day

a little at a time while the tide keeps

coming in faster the waves get bigger

building on each other breaking records

this is not the world that I remember

then comes the day when I open the box

that I remember packing with such care

and there is the face that I had known well

in little pieces staring up at me

it is not mentioned on the front pages

but somewhere far back near the real estate

among the things that happen every day

to someone who now happens to be me

and what can I do and who can tell me

then there is what the doctor comes to say

endless patience will never be enough

the only hope is to be the daylight

The decades reveal more than a poetic autobiography but also nothing less: the evolution of a poet in the pages of a magazine in a way that we are not likely to see again. May he still sing among the trees.

Khong Lo

Vietnamese

medieval, Ly dynasty

died 1119

Vietnamese

medieval, Ly dynasty

died 1119

The Ideal

Retreat

I will

choose a place where the snakes feel safe.

All day I will love that remote country.

At times I will climb the peak of its lonely mountain

to stay and whistle until the sky grows cold.

All day I will love that remote country.

At times I will climb the peak of its lonely mountain

to stay and whistle until the sky grows cold.

1967,

translated with

Nguyen Ngoc Bich

Nguyen Ngoc Bich

Trong bài tưởng

niệm NTN trên Hậu Vệ, Nguyễn Đạt viết:

Nhà thơ Nguyễn

Đăng Thường thấy thơ Nhan trong Thánh Ca “có tí hương vị Rimbaud, một

Rimbaud

không vô thần”, thì tôi cho rằng, trong bản chất thi sĩ của hai người,

Nhan và

Rimbaud, ít nhiều có chỗ giống nhau. Tôi biết rõ, Nhan không đọc một

dòng thơ

nào của Rimbaud, không một dòng thơ dòng văn nào của bất cứ nhà thơ nhà

văn nhà

triết học nào của phương Tây. Và tôi lại thấy Nhan, trong Thánh Ca, có

nhiều

hương vị Phạm Công Thiện. Và tôi hiểu, cả hai, Nhan và Phạm Công Thiện:

ngôn ngữ

của thi sĩ, sản sinh từ cùng một ly nước, một ly nước có chất cà phê

hay men rượu

mà cả hai đã uống.

Source

Theo Gấu, thơ NTN chẳng có tí Rimbaud, mà cũng chẳng có tí PCT, nhưng rõ ràng là có chất Thiền, một thứ Thiền của Việt Nam.

Trước 1975, tình cờ GNV có đọc một bài thơ của anh, viết về một nhà sư Việt Nam, sư Không Lộ, hình như vậy, trên Thời Tập, và như còn nhớ được, chất Thiền mạnh lắm.

Theo như trí nhớ tồi tệ của GCC, bài thơ của Nguyễn Tôn Nhan, về Không Lộ, có cái ý “thét lên 1 tiếng lạnh hư không”, chắc là bài thơ trên, được W.S. Merwin và Nguyễn Ngọc Bích chuyển qua tiếng Mẽo

Source

Theo Gấu, thơ NTN chẳng có tí Rimbaud, mà cũng chẳng có tí PCT, nhưng rõ ràng là có chất Thiền, một thứ Thiền của Việt Nam.

Trước 1975, tình cờ GNV có đọc một bài thơ của anh, viết về một nhà sư Việt Nam, sư Không Lộ, hình như vậy, trên Thời Tập, và như còn nhớ được, chất Thiền mạnh lắm.

Theo như trí nhớ tồi tệ của GCC, bài thơ của Nguyễn Tôn Nhan, về Không Lộ, có cái ý “thét lên 1 tiếng lạnh hư không”, chắc là bài thơ trên, được W.S. Merwin và Nguyễn Ngọc Bích chuyển qua tiếng Mẽo

Nơi

thần sầu

để rút dù

Tớ sẽ chọn một nơi mà rắn

[độc hay không độc] cảm thấy an toàn

Cả ngày tớ sẽ mê cái “lost domain” xa xôi đó

Tớ sẽ leo lên cái đỉnh núi trơ cu lơ của nó

Đếch thèm tìm bản chúc thư [của MT], hay xác con gấu, hay con cáo gì gì đó [của Hemingway]

Mà để hét lên 1 tiếng lạnh hư không!

Cả ngày tớ sẽ mê cái “lost domain” xa xôi đó

Tớ sẽ leo lên cái đỉnh núi trơ cu lơ của nó

Đếch thèm tìm bản chúc thư [của MT], hay xác con gấu, hay con cáo gì gì đó [của Hemingway]

Mà để hét lên 1 tiếng lạnh hư không!

Osip

Mandelstam

LENINGRAD

Russian

1891-1938

I've come

back to my city. These are my own old tears,

my own little veins, the swollen glands of my childhood.

my own little veins, the swollen glands of my childhood.

So you're

back. Open wide. Swallow

the fish oil from the river lamps of Leningrad.

the fish oil from the river lamps of Leningrad.

Open your

eyes. Do you know this December day,

the egg yolk with the deadly tar beaten into it?

the egg yolk with the deadly tar beaten into it?

Petersburg!

I don't want to die yet!

You know my telephone numbers.

You know my telephone numbers.

Petersburg!

I've still got the addresses:

I can look up dead voices.

I can look up dead voices.

I live on

back stairs, and the bell,

torn-out nerves and all, jangles in my temples.

torn-out nerves and all, jangles in my temples.

And I wait

till morning for guests that I love,

and rattle the door in its chains.

and rattle the door in its chains.

Leningrad.

December 1930

1972,

translated with

Clarence Brown

W.S. Merwin

Clarence Brown

W.S. Merwin

I returned

to my city, familiar to tears,

to my childhood's tonsils and

varicose veins.

to my childhood's tonsils and

varicose veins.

You have

returned here-then swallow

the Leningrad street-lamps' cod-liver oil.

the Leningrad street-lamps' cod-liver oil.

Recognize

now the day of December fog

when ominous street-tar is mixed with the yolk of egg.

when ominous street-tar is mixed with the yolk of egg.

Petersburg,

I do not want to die yet

I have your telephone numbers in my head.

I have your telephone numbers in my head.

Petersburg,

I still have addresses at which

I will find the voice of the dead.

I will find the voice of the dead.

I live on a

black stair, and into my temple

strikes the doorbell, torn out with flesh.

strikes the doorbell, torn out with flesh.

And all

night long I await the dear guests,

and I jangle my fetters, the chains on the door.

and I jangle my fetters, the chains on the door.

[Osip

Mandelstam, Selected Poems,

translated by David McDuff. Cambridge: River Press,

1973, p.111] (1)

Tôi trở lại

thành phố của tôi, thân quen với những

dòng lệ,

với cơn đau thịt thừa trong cổ họng thuở ấu thơ,

và chứng chướng tĩnh mạch

Bạn đã trở về đây - vậy thì hãy nuốt

dầu đèn phố Leningrad

với cơn đau thịt thừa trong cổ họng thuở ấu thơ,

và chứng chướng tĩnh mạch

Bạn đã trở về đây - vậy thì hãy nuốt

dầu đèn phố Leningrad

Hãy nhận ra

bây giờ ngày tháng Chạp mù sương...

Petersburg, tôi chưa muốn chết

Tôi có số điện thoại của bạn ở trong đầu Petersburg,

tôi vẫn có những địa chỉ, tại đó, tôi sẽ tìm ra tiếng nói của những người đã chết...

Petersburg, tôi chưa muốn chết

Tôi có số điện thoại của bạn ở trong đầu Petersburg,

tôi vẫn có những địa chỉ, tại đó, tôi sẽ tìm ra tiếng nói của những người đã chết...

Nhà thơ nhà

nước Mẽo, đã từng đợp Pulitzer, nhưng còn là 1 dịch giả thần sầu. Gấu

thèm cuốn

này lâu rồi, bữa nay đành tậu về. Ông còn một cuốn dịch thơ haiku của

Buson, cũng

mới ra lò, 2013, Gấu cũng thèm lắm!

W. S. MERWIN

1927-

1927-

The

following poem inspires us to reflect on what seldom crosses our minds.

After all

(literally after all), such an anniversary awaits every one of us.

Bài thơ sau đây gợi hứng cho chúng ta, về cái điều hiếm chạy qua đầu chúng ta.

Nói cho cùng, "kỷ niệm cái chết của tôi" đâu bỏ quên, bất cứ ai?

Czeslaw Milosz

Bài thơ sau đây gợi hứng cho chúng ta, về cái điều hiếm chạy qua đầu chúng ta.

Nói cho cùng, "kỷ niệm cái chết của tôi" đâu bỏ quên, bất cứ ai?

Czeslaw Milosz

Every year

without knowing it I have passed the day

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam of a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam of a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

Guillaume

Apollinaire

French

1880-1918

French

1880-1918

Under the

Mirabeau Bridge the Seine

Flows and our love

Must I be reminded again

How joy came always after pain

Flows and our love

Must I be reminded again

How joy came always after pain

Night comes

the hour is rung

The days go I remain

The days go I remain

Hands within

hands we stand face to face

While underneath

The bridge of our arms passes

The loose wave of our gazing which is endless

While underneath

The bridge of our arms passes

The loose wave of our gazing which is endless

Night comes

the hour is rung

The days go I remain

The days go I remain

Love slips

away like this water flowing

Love slips away

How slow life is in its going

And hope is so violent a thing

Love slips away

How slow life is in its going

And hope is so violent a thing

Night comes

the hour is rung

The days go I remain

The days go I remain

The days

pass the weeks pass and are gone

Neither time that is gone

Nor love ever returns again

Under the Mirabeau Bridge Flows the Seine

Neither time that is gone

Nor love ever returns again

Under the Mirabeau Bridge Flows the Seine

Night comes

the hour is rung

The days go I remain

The days go I remain

1956

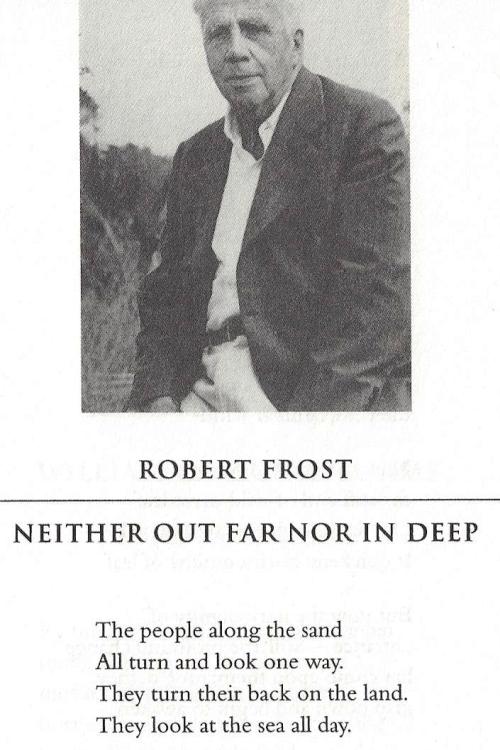

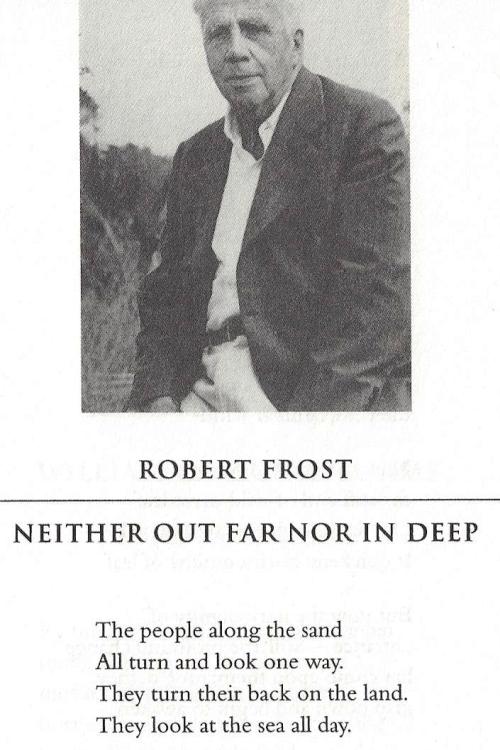

ROBERT

FROST

NEITHER OUT

FAR NOR IN DEEP

The people

along the sand

All turn and look one way

They turn their back on the land.

They look at the sea all day.

All turn and look one way

They turn their back on the land.

They look at the sea all day.

As long as

it takes to pass

A ship keeps raising its hull;

The wetter ground like glass

Reflects a standing gull.

A ship keeps raising its hull;

The wetter ground like glass

Reflects a standing gull.

The land may

vary more;

But wherever the truth may be-

The water comes ashore,

And the people look at the sea.

But wherever the truth may be-

The water comes ashore,

And the people look at the sea.

They cannot

look out far.

They cannot look in deep.

But when was that ever a bar

To any watch they keep?

They cannot look in deep.

But when was that ever a bar

To any watch they keep?

Không xa mà

cũng chẳng sâu

Ném mẩu thuốc

cuối cùng xuống dòng sông

Mà lòng mình phơi trên kè đá

TTT

Mà lòng mình phơi trên kè đá

TTT

Đám người dọc

theo cát

Tất cả quay và nhìn một phía.

Lưng xoay vô đất

Mắt nhìn biển cả ngày.

Tất cả quay và nhìn một phía.

Lưng xoay vô đất

Mắt nhìn biển cả ngày.

Con tàu dâng thân lên

Chừng nào nó đi qua

Thân tầu, lóng lánh như mặt gương,

Phản chiếu một hải âu đứng sững.

Chừng nào nó đi qua

Thân tầu, lóng lánh như mặt gương,

Phản chiếu một hải âu đứng sững.

Đất có thể

tang thương như thế nào

Một khi sự thực thì như thế nào đó –

Nước vẫn tạt vô bờ

Và mọi người nhìn ra biển

Một khi sự thực thì như thế nào đó –

Nước vẫn tạt vô bờ

Và mọi người nhìn ra biển

Họ không thể

nhìn xa

Họ không thể nhìn sâu

Nhưng liệu có 1 cái kè đá nào

Cho bất cứ 1 cái nhìn mà họ giữ?

Họ không thể nhìn sâu

Nhưng liệu có 1 cái kè đá nào

Cho bất cứ 1 cái nhìn mà họ giữ?

Ui chao đọc

bài thơ này, thì bèn nghĩ liền đến bài thơ của Gấu!

Buổi

chiều đứng trên bãi Wasaga

Nhìn hồ Georgian

Cứ nghĩ thềm bên kia là quê nhà.

Nhìn hồ Georgian

Cứ nghĩ thềm bên kia là quê nhà.

Sóng

đẩy biển lên cao, khi xuống kéo theo mặt trời

Không gian bỗng đỏ rực rồi đêm tối trùm lên tất cả

Không gian bỗng đỏ rực rồi đêm tối trùm lên tất cả

Cát

ở đây được con người chở từ đâu tới

Còn ta bị quê hương ruồng bỏ nên phải đứng ở chốn này

Còn ta bị quê hương ruồng bỏ nên phải đứng ở chốn này

Số

phận còn thua hạt cát.

Hàng

cây trong công viên bên đường nhớ rừng

Cùng thi nhau vươn cao như muốn trút hết nỗi buồn lên trời

Cùng thi nhau vươn cao như muốn trút hết nỗi buồn lên trời

Chỉ

còn ta cô đơn lẫn vào đêm

Như con hải âu già

Giấu chút tình sầu

Vào lời thì thầm của biển...

Như con hải âu già

Giấu chút tình sầu

Vào lời thì thầm của biển...

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/09/18/the-ascetic-insight-of-w-s-merwin

The Ascetic

Insight of W. S. Merwin

After

escaping the anxiety of influence, the poet discovered a brilliant, elemental

poetry.

By Dan

Chiasson

Merwin,

shown circa 1972, has deepened poetry by extracting its essence.

Photograph

by Douglas Kent Hall / ZUMA Press

The American

poet W. S. Merwin, who turns ninety this year, has for decades written his

scanty, unpunctuated poems from a palm forest on the remote north shore of

Maui. Merwin bought the property in 1977, and began restoring the ancient trees

lost when loggers and the commercial pineapple and sugar farmers started to

move in more than a century ago. “After an age of leaves and feathers / someone

dead / thought of this mountain as money,” Merwin writes in “Rain at Night.” He

has reclaimed the mountain, and much else, for poetry. His poems, written in an

environment refashioned by his hard restorative work, are adjuncts of that

work, and operate according to their own stringent verbal restrictions. Wallace

Stevens called his collected poems “The Planet on the Table”; Merwin’s work is

more like a terrarium on the table, its elements balanced and tended in an

eerie simulacrum of reality.

“The

Essential W. S. Merwin” (Copper Canyon) condenses the poet’s nearly seventy-year

career into a single volume. Merwin’s poems, like his Maui conservancy, make

their mark on the world by recording its effacement; they reveal what a person

finds when he imagines himself as having been superseded. Here is perhaps his

most famous poem, “For the Anniversary of My Death”:

Every year

without knowing it I have passed the day

When the

last fires will wave to me

And the

silence will set out

Tireless

traveler

Like the

beam of a lightless star

Then I will

no longer

Find myself

in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at

the earth

And the love

of one woman

And the

shamelessness of men

As today

writing after three days of rain

Hearing the

wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing

not knowing to what

The poem’s

power is clinched by its title and opening line; almost anything could follow

that bracing conceit. It must have been a struggle, once Merwin had come to

this startling idea, to decide when and how to deploy it. He was in his

thirties when the poem was written. It faintly mocks its own stodginess—it is a

kind of pleasure, after all, to imagine your own death, provided you’re young

and healthy. A pleasure and an opportunity: the poem strongly implies the

seduction plot that it doesn’t mention outright. The candles wave, the garments

fall away, and this man’s “shamelessness” meets, in the aura of his personal

doomsday, “the love of one woman.” Something deep in me resists this sexy

self-extinction rhetoric. Soft-core, low-fi, and Aquarian, Merwin’s asceticism

has always had about it the prowess of a sophisticate.

From the

beginning, he wanted to mesmerize. In the forties, under the spell of his

Princeton teachers John Berryman and R. P. Blackmur, he perfected a learned,

ominous, allegorical poem, mopping up for the high modernists. In “A Mask for

Janus” (1952), his début collection, chosen by W. H. Auden for the Yale Series

of Younger Poets, the thread count is high but the starch is unbearable. In one

poem, “Dictum: For a Masque of Deluge,” Noah, post-flood, finds he has his work

cut out for him:

At last the

sigh of recession: the land

Wells from

the water; the beasts depart; the man

Whose

shocked speech must conjure a landscape

As of some

country where the dead years keep

A circle of

silence, a drying vista of ruin,

Musters

himself, rises . . .

It helps to

think of the “drying vista of ruin” as an image of war, but this animatronic

Noah, who weirdly “musters himself” while the beasts “depart,” is a clunky

vehicle for expressing majesty. When the batteries in Merwin’s early methods

ran out, mercifully he never replaced them.

It took

Merwin several volumes before arriving at a style barren and bleak enough to

make his pronouncements on life’s barrenness and bleakness feel persuasive.

“The Lice” (1967) was his breakthrough. It remains one of the indelible books

about Vietnam: the images coming out of the war suggested, to Merwin, the utter

defenselessness of a traditional culture against the fury of modernity. It

seems to me that Merwin wanted these new poems to channel apocalyptic prophecy

without suggesting that he was its source. Add punctuation to these lines from

“The Hydra,” and Merwin sounds like his Noah action figure. Strip it back out,

and we have the distinct power of the poet at his finest:

I was young

and the dead were in other Ages

As the grass

had its own language

Now I forget

where the difference falls

One thing

about the living sometimes a piece of us

Can stop

dying for a moment

But you the

dead

Once you go

into those names you go on you never

Hesitate

You go on

The phrases

are like driftwood scattered on the sand which nevertheless suggest the outline

of a form; their dispersal on the page is the source of their power.

Punctuation would suture the strewn bits together, like the prosthetic joints

you find linking the real bones in a brontosaurus skeleton. The effect is

especially strong in that last stanza: a period or a colon after “hesitate,”

and the range of its power is drastically narrowed. Those final two lines work

as contradictory imperatives, like the commands in the story of Mr. Fox: Be

bold, but not too bold.

Merwin’s

verse often gives the impression of language scavenged from the elements, its

power reckoned only as its meanings assemble, phrase by phrase, against the

white of the page. Simple astonishment, one of the rarest of all literary

experiences, is the most potent outcome; in Merwin’s best poems, he seems

brought up short by his own discoveries. It is another advantage of his style

that it can end without ending, as it does in “James”:

News comes that

a friend far away

is dying now

I look up

and see small flowers appearing

in spring

grass outside the window

and can’t

remember their name

The beauty

of this elegy is in its pair of mirrored participles, “dying” and “appearing”:

the mind toggles between memory and perception, between the “far away” but

emotionally pressing matter of the friend’s death and the close but suddenly

blurry appearance of the flowers, which now have a new name, James. The flowers

and the friend exist in a permanent reciprocity established by this little

lyric. An instant later, perhaps, Merwin remembers the flowers’ actual name;

the poem suspends us between recollection and forgetting, right in the spot

where elegy is most poignant and effective.

Merwin’s

poems seem made from a kit, a highly personalized but weirdly plain repertoire

of details: rain, light, mountains, water, wind. Since his fundamental stance

is passivity, Merwin’s language can’t feel as though it were summoned from too

much effort of learning, or from casually gleaned perception or overheard

conversation, which would concede the existence of actual other people. The “I”

finds itself, instead, in the combination of those primeval elements: wind

across the water, light on the mountain. This “I” has emotions, but they drift

in from elsewhere; the vessel is empty until sadness, or grief, or expectation

blows in and settles briefly inside it.

It is not

hard to imagine how this kind of writing could go awry, and Merwin’s attempts

to expand his range of subjects to the social or the overtly political often

expose his limits. But a sly ars poetica, “Song of Man Chipping an Arrowhead,”

makes his case:

Little

children you will all go

but the one

you are hiding

will fly

The “little

children” here are mortals too young to exist woefully in time, but also shards

of flint that “go” in service of the core function of the stone. As with any

art of imposed constraint, we look for the moments when the constraints are

defied. Once you carve the arrowhead, it can “fly” on its own; its nature as a

stone has been transformed, just as the nature of these words, bought for

nothing, is transformed. When Merwin’s poems don’t move along this axis of

transformation, when they start too broad or loquacious, they lose their power.

Yet anybody

who wants to learn about Merwin’s hardscrabble, very American childhood as the

son of a violent minister, or his time as a scholarship student at Princeton,

or his successful forays into the worlds of American and European peerage

should read his wonderful prose memoirs. My favorite is “Summer Doorways,”

which is mainly about his time in France, where he keeps a home. Merwin’s prose

is lush, companionable, and funny, alert to the ironies of everyday life and

utterly unlike his flinty poems. You surmise, reading his memoirs, that poetry

is for him a quite distinct animal, specialized, like an arrowhead carved from

stone, from every use but its intrinsic one. As he has held poetry to its

essence, he has deepened it. And his poems in old age attain a special kind of

power only available to an artist who works the same furrows over and over.

Merwin’s

recent work often recalls his monitoring intelligence from its mission in the

landscape to the wreck of his own aged body, itself now a part of the world of

matter so resistant to human transformation. The fresh appraisal of his old

face, in “To the Face in the Mirror,” draws on the tradition of mirror poems

extending from Shakespeare to Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell, and John Ashbery.

The eye you see in the mirror is lit up by the sight of you; the mind,

revelling in the transaction, records it, but in the process involves itself

inside the exchange:

so how far

away are you

after all

who seem to be

so near and

eternally

out of reach

you with the

white hair

now who

still surprise me

day after

day

staring back

at me

out of

nowhere

past present

or future

you with no

weight or name

no will of

your own

and the

sight of me

shining in

your eye

how do you

know it is

me

The poem

reminds us, as the image in the mirror reminds Merwin, of how much has gone on

inside the mind and how little trace its activity leaves on the material world.

Merwin’s insistence on a poetry of imaginative utility, against the

encroachments of decades of literary fads, has succeeded in giving his imagined

worlds some of the tangible pleasures and horrors we associate with real ones.

Like Stevens, whose old-age poems are perhaps the greatest ever written, Merwin

can say he “recomposed” the constituents of his vision. But he also planted and

tended a palm forest that is now permanently protected and open to the public.

His poems, like that forest, are a kind of time preserve. Until you can make it

to Maui, the poems will have to do. Many of them will be around as long as the

palms. ♦

This article

appears in the print edition of the September 18, 2017, issue, with the

headline “The Ascetic.”

Comments

Post a Comment