Rilke by AZ

THE FIRST ELEGY

Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the Angels?

Orders? and even if one of them pressed me

suddenly to his heart: I'd be consumed

in his more potent being. For beauty is nothing

but the beginning of terror, which we can still barely endure,

and while we stand in wonder it coolly disdains

to destroy us. Every Angel is terrifying.

Orders? and even if one of them pressed me

suddenly to his heart: I'd be consumed

in his more potent being. For beauty is nothing

but the beginning of terror, which we can still barely endure,

and while we stand in wonder it coolly disdains

to destroy us. Every Angel is terrifying.

Ai, nếu tôi kêu lớn, sẽ nghe, giữa những Thiên

Thần?

Những Thiên Sứ? và ngay cả nếu một vị trong họ ôm chặt tôi vào tận tim:

Tôi sẽ bị đốt cháy trong hiện hữu dữ dằn của Người.

Bởi là vì, cái đẹp chẳng là gì, mà chỉ là khởi đầu của ghê rợn,

chúng ta vẫn có thể chịu đựng, và trong khi chúng ta đứng ngẩn ngơ,

thì nó bèn khinh khi hủy diệt chúng ta.

Mọi Thiên Thần thì đều đáng sợ.

Những Thiên Sứ? và ngay cả nếu một vị trong họ ôm chặt tôi vào tận tim:

Tôi sẽ bị đốt cháy trong hiện hữu dữ dằn của Người.

Bởi là vì, cái đẹp chẳng là gì, mà chỉ là khởi đầu của ghê rợn,

chúng ta vẫn có thể chịu đựng, và trong khi chúng ta đứng ngẩn ngơ,

thì nó bèn khinh khi hủy diệt chúng ta.

Mọi Thiên Thần thì đều đáng sợ.

Rilke

For me, the happy owner of the

elegant slim book bought long ago, the Elegies represented just the beginning

of a long road leading to a better acquaintance with Rilke's entire oeuvre.

The fiery invocation that starts “The First Elegy” - once again: "Who, if

I cried out, would hear me among the Angels' / Orders? And even if one of

them pressed me / suddenly to his heart: 1'd be consumed / in his more potent

being. For beauty is nothing / but the beginning of terror, which we can

still barely endure" -had become for me a living proof that poetry hadn't

lost its bewitching powers. At this early stage I didn't know Czeslaw Milosz's

poetry; it was successfully banned by the Communist state from the schools,

libraries, and bookstores-and from me. One of the first contemporary poets

I read and tried to understand was Tadeusz Rozewicz, who then lived in the

same city in which I grew up (Gliwice) and, at least hypothetically, might

have witnessed the rapturous moment that followed my purchase of the Duino

Elegies translated by Jastrun, might have seen a strangely immobile boy standing

in the middle of a side- walk, in the very center of the city, in its main

street, at the hour of the local promenade when the sun was going down and

the gray industrial city became crimson for fifteen minutes or so. Rozewicz's

poems were born out of the ashes of the other war, World War II, and were

themselves like a city of ashes. Rozewicz avoided metaphors in his poetry,

considering any surplus of imagination an insult to the memory of the last

war victims, a threat to the moral veracity of his poems; they were supposed

to be quasi-reports from the great catastrophe. His early poems, written before

Adorno uttered his famous dictum that after Auschwitz poetry's competence

was limited-literally, he said, "It is barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz"-were

already imbued with the spirit of limitation and caution.

Adam Zagajewski: Introduction

Với tôi người sở hữu hạnh phúc, cuốn sách thanh

nhã, mỏng manh, mua từ lâu, “Bi Khúc” tượng trưng cho một khởi đầu của con

đường dài đưa tới một quen biết tốt đẹp hơn, với toàn bộ tác phẩm của Rilke.

“Bi Khúc thứ nhất” - một lần nữa ở đây: “Ai, nếu tôi la lớn - trở thành một

chứng cớ hiển nhiên, sống động, thơ ca chẳng hề mất quyền uy khủng khiếp của

nó. Vào lúc đó, tôi chưa biết thơ của Czeslaw Milosz, bị “VC Ba Lan”, thành

công trong việc tuyệt cấm, ở trường học, nhà sách, thư viện, - và tất nhiên,

tuyệt cấm với tôi. Một trong những nhà thơ cùng thời đầu tiên mà tôi đọc

và cố hiểu, là Tadeusz Rozewicz, cùng sống trong thành phố mà tôi sinh trưởng, (Gliwice), và, có thể chứng kiến, thì cứ giả dụ như vậy, cái giây

phút thần tiên liền theo sau, khi tôi mua được Duino Elegies, bản

dịch của Jastrun - chứng kiến hình ảnh một đứa bé đứng chết sững trên hè

đường, nơi con phố trung tâm thành phố, vào giờ cư dân của nó thường đi dạo

chơi, khi mặt trời xuống thấp, và cái thành phố kỹ nghệ xám trở thành 1 bông

hồng rực đỏ trong chừng 15 phút, cỡ đó – ui chao cũng chẳng khác gì giây

phút thần tiên Gấu đọc cọp cuốn “Bếp Lửa”, khi nó được nhà xb đem ra bán

xon trên lề đường Phạm Ngũ Lão, Sài Gòn – Thơ của Rozewicz như sinh ra từ

tro than của một cuộc chiến khác, Đệ Nhị Chiến, và chính chúng, những bài

thơ, thì như là một thành phố của tro than. Rozewicz tránh sử dụng ẩn dụ trong thơ của mình,

coi bất cứ thặng dư của tưởng tượng là 1 sỉ nhục hồi ức những nạn nhân của

cuộc chiến sau chót, một đe dọa tính xác thực về mặt đạo đức của thơ ông:

Chúng được coi như là những bản báo cáo, kéo, dứt, giựt ra từ cơn kinh hoàng,

tai họa lớn. Những bài thơ đầu của ông, viết trước khi Adorno phang ra đòn

chí tử, “thật là ghê tởm, man rợ khi còn làm thơ sau Lò Thiêu”, thì đã hàm

ngụ trong chúng, câu của Adorno rồi.

Note: Có 1 sự trùng hợp ngẫu

nhiên, nhưng thật ly kỳ thú vị, không chỉ về cái cảnh Gấu chết sững trong

nắng Sài Gòn, khi đọc cọp – khám phá ra - Bếp Lửa, khi cuốn sách được nhà xb Nguyễn

Đình Vượng cho đem bán xon trên hè đường Phạm Ngũ Lão, nhưng còn ở điều này:

Cuốn sách Bếp Lửa đã sống lại, từ

tro than, bụi đường Xề Gòn.

Gấu đã viết như thế, về Bếp Lửa, từ năm 1972

Giả như nó không được đem bán xon, liệu có tái sinh?

Quá tí nữa, giả như không có cuộc phần thư 1975, liệu văn học Miền Nam vưỡn còn, và được cả nước nâng niu, trân trọng như bây giờ?

Gấu đã viết như thế, về Bếp Lửa, từ năm 1972

Giả như nó không được đem bán xon, liệu có tái sinh?

Quá tí nữa, giả như không có cuộc phần thư 1975, liệu văn học Miền Nam vưỡn còn, và được cả nước nâng niu, trân trọng như bây giờ?

Hàng

zin, xịn, mới tậu!

Hà, hà!

Hà, hà!

Maybe it’s more interesting

to see Rilke’s work as not as virginal, not as ethereal, as it seems to many

readers. After all, like the majority of literary modernists, he is an antimodern;

one of the main impulses in his work consists of looking for antidotes to

modernity. Heroes of his poems move in a spiritual space, not in the streets

of New York or Paris, but they also, because of their intense existence,

are meant to act against the supposed or real ugliness of the modern world.

Even Rilke’s snobbery, hypothetical or not, can be seen as corresponding more

to his ideas than to the weaknesses of his character: aristocrats represented

for the poet the survivors of a better Europe, a chivalric continent, as

opposed to the degredation caused by profit-oriented modernity, cherishing

mass production and car races. He was not alone in representing this position—it

will be enough to refer to the aesthetic movement and Walter Pater, who preceded

him by one generation. Had Rilke met Marcel Proust, who was born only four

years before our poet (they never met, but we know that Rilke admired the

first volumes of “À la recherche du temps perdu”, published before his death),

we can be sure there would have been between them no major disagreement concerning

matters of philosophy, taste, and society. And certainly he would have readily

agreed with his friend Paul Valéry when the French poet was was sadly sighing

at the sight of a new Europe of efficiency, labor, and military drill, and

when, regretting the loss of the unhurried pace of intellectual work and

musing in the past he pronounced these beautiful words: “Adieu, travaux infiniment

lents . . .”

Some of the more sharp-eyed

scholars have even found one or two sentences in Rilke’s letters in praise

of Mussolini. This is not what I mean: I don’t intend to accuse the superb

poet of any political misdemeanor. What I want is simply also to see in his

poetry a dimension that has a lot to do with the diversity of intellectual

polemics, some of which are still ongoing. We’re still pondering the value

of modernity, as was Rilke, even if we do this using different notions and

examples. We have a new sorrow today: after the terrible catastrophes of

the twentieth century, after the disasters that entered both our memory and

imagination, we tread gingerly at the point where poetry meets society; “Don’t

walk beyond this line,” as the sign on every jetliner’s wing warns us. And

yet the central issue for us is probably the question of whether the mystery

at the heart of poetry (and of art in general) can be kept safe against the

assaults of an omnipresent talkative and soulless journalism and an equally

omnipresent popular science—or pseudo-science. It also has a lot to do with

the weighing of the advantages and vices of mass culture, with the influence

of mass media, and with a difficult search for genuine expression inside

the commercial framework that has replaced older, less vulgar traditions

and institutions in our societies. In this respect, it’s true, poets have

less to fear than their friends the painters, especially the successful ones,

who, because of the absurd prices their works can now command, will never

see their canvases in the houses of their fellow artists, in the apartments

of people like themselves, only in vaults belonging to oil or television

moguls who don’t even have time to look at them. Still, the stakes of the

debate and its seriousness are not very different and not less important

than a hundred years ago.

We know that the main domain

of poetry is contemplation, through the riches of language, of human and

nonhuman realities, in their separateness and in their numerous encounters,

tragic or joyful. Rilke’s powerful Angel standing at the gates of the Elegies,

timeless as he is, is there to guard something that the modern era—which

gave us so much in other fields—took away from us or only concealed: ecstatic

moments, for instance, moments of wonder, hours of mystical ignorance, days

of leisure, sweet slowness of reading and meditating. Ecstatic moments—aren’t

they one of the main reasons why poetry readers cannot live without Rilke’s

work? I mean here readers of contemporary poetry who otherwise are mostly

kept on a rather meager diet of irony. The Angel is timeless, and yet his

timelessness is directed against the deficiencies of a certain epoch. So

is Rilke: timeless and deeply immersed in his own historic time. Not innocent,

though: only silence is innocent, and he still speaks to us.

Trên TV đã có 1 mẩu Adam Zagajiewski

viết về Rilke. Bi giờ, là 1 bài dài thòng! Đọc loáng thoáng trên đường về,

vớ được ý này, mà chẳng khoái sao, đại khái, những bài thơ đầu tay của Rilke,

viết khi Adorno chưa phán, thơ làm chó gì sau Lò Thiêu, tuy nhiên, thơ của

Rilke đếch cần câu phán đó, hay nói rõ hơn, bằng cái sự cẩn trọng, bằng cái

sự cần kiệm, chi ly, nó tiên đoán câu của Adorno!

His early poems, written before

Adorno uttered his famous dictum that after Auschwitz poetry's competence

was limited-literally, he said, "It is barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz"-were

already imbued with the spirit of limitation and caution.

Sunday, December 4, 2011

I would like to sing someone to sleep,

to sit beside someone and be there.

I would like to rock you and sing softly

and go with you to and from sleep.

I would like to be the one in the house

who knew: The night was cold.

And I would like to listen in and listen out

into you, into the world, into the woods.

The clocks shout to one another striking,

and one sees to the bottom of time.

And down below one last, strange man walks by

and rouses a strange dog.

And after that comes silence.

I have laid my eyes upon you wide;

and they hold you gently and let you go

when something stirs in the dark.

~ Rainer Maria Rilke

from The Book of Images

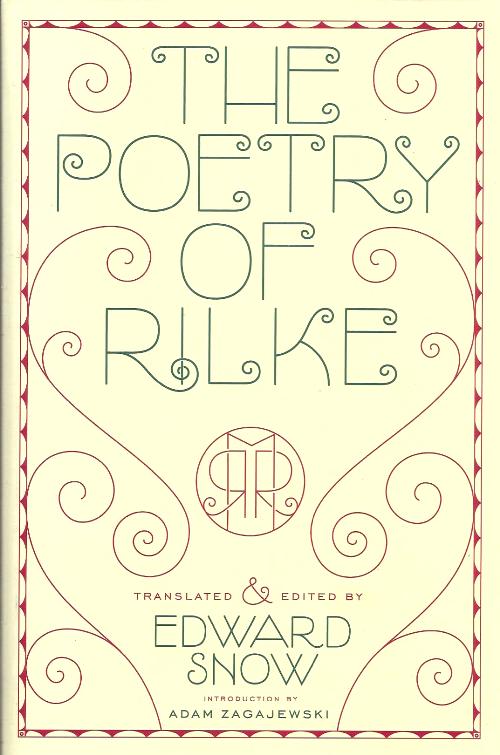

translated by Edward Snow

passport picture 1919

translated by Edward Snow

passport picture 1919

[Nhân sinh nhật em “Valentine”] (1)

Note: Bài thơ trên, có trong

tuyển tập thơ mới mua, có tí khác:

TO SAY BEFORE GOING TO SLEEP

I'd like to

sing someone to sleep,sit beside someone and be there.

I'd like to rock you and sing softly

and go with you to and from sleep.

I’d like to be the one in the house

who knew: the night was cold.

And I'd like to hear every little stirring

in you, in the world, in the woods.

The clocks call to one another striking,

and one sees to the bottom of time.

And down below a last strange man walks by

and rouses a strange dog.

And after that comes silence.

I have laid my eyes upon you wide;

and they hold you gently and they let you go

when a thing moves in the dark.

THE FIRST ELEGY

Who, if I cried out, would hear

me among the Angels?

Orders? and even if one of them pressed me

suddenly to his heart: I'd be consumed

in his more potent being. For beauty is nothing

but the beginning of terror, which we can still barely endure,

and while we stand in wonder it coolly disdains

to destroy us. Every Angel is terrifying.

Orders? and even if one of them pressed me

suddenly to his heart: I'd be consumed

in his more potent being. For beauty is nothing

but the beginning of terror, which we can still barely endure,

and while we stand in wonder it coolly disdains

to destroy us. Every Angel is terrifying.

Rilke

For me, the happy owner of the

elegant slim book bought long ago, the Elegies represented just the beginning

of a long road leading to a better acquaintance with Rilke's entire oeuvre.

The fiery invocation that starts “The First Elegy” - once again: "Who, if

I cried out, would hear me among the Angels' / Orders? And even if one of

them pressed me / suddenly to his heart: 1'd be consumed / in his more potent

being. For beauty is nothing / but the beginning of terror, which we can

still barely endure" -had become for me a living proof that poetry hadn't

lost its bewitching powers. At this early stage I didn't know Czeslaw Milosz's

poetry; it was successfully banned by the Communist state from the schools,

libraries, and bookstores-and from me. One of the first contemporary poets

I read and tried to understand was Tadeusz Rozewicz, who then lived in the

same city in which I grew up (Gliwice) and, at least hypothetically, might

have witnessed the rapturous moment that followed my purchase of the Duino Elegies translated by Jastrun, might have seen a strangely

immobile boy standing in the middle of a side- walk, in the very center of

the city, in its main street, at the hour of the local promenade when the

sun was going down and the gray industrial city became crimson for fifteen

minutes or so. Rozewicz's poems were born out of the ashes of the other war,

World War II, and were themselves like a city of ashes. Rozewicz avoided metaphors

in his poetry, considering any surplus of imagination an insult to the memory

of the last war victims, a threat to the moral veracity of his poems; they

were supposed to be quasi-reports from the great catastrophe. His early poems,

written before Adorno uttered his famous dictum that after Auschwitz poetry's

competence was limited-literally, he said, "It is barbaric to write poetry

after Auschwitz"-were already imbued with the spirit of limitation and caution.

Adam Zagajewski:

Introduction

Comments

Post a Comment