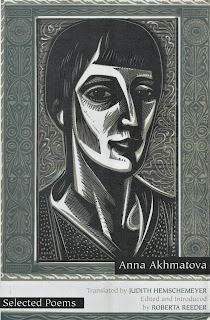

Anna Akhmatova: Selected Poems

TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE

JUDITH HEMSCHEMEYER

In 1973 I read a few of Anna Akhmatova's poems in translation in the “American Poetry Review” and was so struck by one of them that I decided to learn Russian in order to read them all. Here is the poem, from “White Flock, Akhmatova's third book:

The sky’s dark blue lacquer has dimmed,

And louder the song of the ocarina.

It's only a little pipe of clay,

There's no reason for it to complain.

Who told it all my sins,

And why is it absolving me?...

Or is this a voice repeating

Your latest poems to me?

Three years later, when I could read the Russian and compare the existing, "selected Akhmatova" translations with the originals, I became convinced that Akhmatova’s poems should be translated in their entirety, and by a woman poet, and that I was that person. Using literals provided by Ann Wilkinson for the first 300 poems and by Natasha Gurfinkel and Roberta Reeder for the rest, I translated the poems in the order established by the Formalist critic Viktor Zhirmunsky in the Biblioteka Poeta edition of Akhmatova's works, published in Leningrad in 1976. Zhirmunsky reproduced Akhmatova's five early, uncensored books — Evening (1912), Ro-sary (1914), White Flock (1917), Plantain (1921), and Anno Domini MCMXXI (1922) — in the order in which they were published. Just as important, he retained the poet's ordering of the poems within each volume; this allows us to participate in Akhmatova's life and loves as she orchestrated them.

The act of translating, as anyone who has tried it will attest, entails sacrifices. For the music and the delicious web of connotations of the original one substitutes, if one is lucky and patient, a verbal equivalent that conveys the tone and the meaning and some kind of music of its own. The music of a translation is not the original music, of course. My suggestion is that the English-speaking reader find a Russian friend to read aloud (or recite, as many Russians will be able to do) some of the poems and thus gain some idea of the rich texture of sounds and the driving rhythms that Akhmatova achieves.

My first goal was to understand the poem; only then, I felt, could I present the poem to others. This took time — more than ten years — and at least several versions of each poem.

Because the Russian language has six cases, it is extremely rich in full rhymes, while English is extremely poor. To illustrate: how many words in English rhyme with father? The word father in Russian is, depending on its case, pronounced “ot-yets, ot-sa, ot-su, ot-se” or “ot-som”. The plural endings present another set of rhyming possibilities. Thus, in Russian almost any noun can be made to rhyme with any other noun. Adjectives, too, are declined — even the numbers — and verbs are conjugated; this enriches the chance for rhyming as well. Word order in the English sentence is fair-ly rigid, but the case endings in Russian allow for all sorts of flexibility, hence still more rhyming possibilities.

A typical lyric of Alchmatova's was 12 or 16 lines, three or four stanzas, rhymed a-b-a-b, c-d-c-d, etc. To reproduce this as full rhyme in English, one would have to skew the sense of the poem by reaching for a rhyming word at the expense of the meaning. And the result would be a trite-sounding series of jingles whose rhymes are boringly anticipated by the reader, a sort of doggerel.

I chose instead to utilize the occasional full rhyme that occurred, but to rely mainly on slant rhyme, internal rhyme, assonance and alliteration to construct the poem in English. What I found myself producing as the work went on was often an x-a-y-a rhyme scheme, one that satisfies but doesn't cloy the ear.

As for rhythm — the Russian language has a wealth of magnificent polysyllabic words and since each word gets only one accent, the good poet can command a healthy variation of metrical feet in the line. Akhmatova was a master of prosody. She used an exceptionally high number of amphibrachs — an unaccented syllable, an accented syllable, then another unaccented syllable — with the effect of suggesting rising and falling, tension and release. It was, of course, impossible to ad-here to Akhmatova's exact meters and say in English what has to be said. But I repeated the poem over and over to myself in Russian to get the rhythm. Then, using the literal translation as a base, I would invite felicitous English words to alight in some kind of regular line.

I was very careful to retain Akhmatova's verbs and Akhmatova’s images and I found, I think, an equivalent for her diction, which is direct but not slangy, precise but never precious. I did not add lines of explication in the body of the poem; endnotes take care of that. I also tried, as far as possible, to keep Akhmatova's line breaks and the look of the poem on the page.

Here is a sonnet Akhmatova wrote in 1962, remembering the visit Isaiah Berlin paid to her. Her sonnet rhymes a-b-a-b, c-d-c-d, e-e-f, g-g-f and has lines of 10 and 9 syllables. My translation rhymes a-b-b-a,c-d-d-c,b-e-e, f-g-g. Some of my rhymes are direct, some are slant rhymes.

I abandoned your shores, Empress, against my will.

— Aeneid, Book 6

Don't be afraid — I can still portray

What we resemble now.

You are a ghost — or a man passing through,

And for some reason I cherish your shade.

For awhile you were my Aeneas —

It was then I escaped by fire.

We know how to keep quiet about one another.

And you forgot my cursed house.

You forgot those hands stretched out to you

In horror and torment, through flame,

And the report of blasted dreams.

You don't know for what you were forgiven...

Rome was created, flocks of flotillas sail on the sea,

And adulation sings the praises of victory.

Although I aimed for a basic decasyllabic line, I also wanted to have the meaning of each line in English match its Russian counterpart. Consequently, line 2 has only 6 syllables and there are other lines of 13 or 14 syllables. Still, it is a recognizable sonnet, and it says, as gracefully as I found possible, what Akhmatova's sonnet says.

Each poem presented a new puzzle; many defied the rough formula I had devised of rhyming the second and fourth line of Akhmatova's quatrain. In this poem, for example, the end rhymes are a-b-a-b, c-d-c-d, e-f-e-f in Russian.

THE LAST ONE

I delighted in deliriums,

In singing about tombs.

I distributed misfortunes

Beyond anyone's strength.

The curtain not raised,

The circle dance of shades —

Because of that, all my loved ones

Were taken away.

All this is disclosed

In the depths of the roses.

But I am not allowed to forget

The taste of the tears of yesterday.

What I have managed to devise and still stay faithful to the meaning and the line breaks is the consonance of "deliriums" and "tombs," the assonance of "deliriums" and "misfortunes," the alliteration of "delighted," "deliriums" and "distributed," the rhyming of "disclosed" and rose" and the five long “a” sounds that, because they are so strong in English, provide the poem’s dominant musical chord: "raised," "shades," "away," "taste" and "yesterday."

Because of the high achievement of Akhmatova’s poetry, I never begrudged the hours and years of labor it took to solve these puzzles, these poems, one after the other. What emerges from my efforts are, I hope, translations that will give the reader of English some idea of the intensity with which Akhmatova lived and wrote.

As time elapsed, I learned about her not only through her poems, but through the writings of her contemporaries, and the more I learned, the more I admired her courage, her moral integrity, her wit and, yes, her sense of humor under the direst of circumstances. Nadezhda Mandelstam has this to say about Akhmatova's character in Hope Abandoned:

One way or another I expect I shall now live out my life to the end, spurred on by the memory of Akhmatova’s Russian powers of endurance; it was her boast to have so exasperated the accusers who had denounced her and her poetry that they all died before her of heart attacks.

Judith Hemschemeyer

Comments

Post a Comment