Olga Tokarczuk -Nobel văn chương 2018 - trả lời tờ "The Paris Review" Spring 2023

Bài này tuyệt lắm. Vị này, Ba Lan, nhưng khác với Ba Lan của Milosz, vì ông tự coi diểm xuất phát của ông là Âu châu, dù 1 Âu Châu khác.

INTERVIEWER

What was it like to grow up at a people's university?

TOKARCZUK

There was always something going on—someone stopping by our place, someone dashing out to a night class. The school was housed in a former hunting lodge that had belonged to the aristocratic Radziwill family, and there were a communal dining room and kitchen, dorms for the students, and three or four apartments for faculty. The teachers often arrived in pairs, husband and wife, but there were few children. Often I would sit in on my parents' classes, or dance and sing with their pupils. I thought all schools were like that—I realized only later how ,special it was, how lucky I was to have been immersed in this environment from birth.

Another little girl eventually showed up—the history teacher's daughter—and she and I played together. We had the whole lodge at our disposal, and we often wondered who had lived in this palace before, and why it hadn't been destroyed or looted during the war. There was a ballroom dominated by an enormous fireplace, and when you turned on the vent, it caused a strange echo to reverberate through the pipes. We would pretend that the hearth was a passage to another world. There were a lot of old books around, and paintings and reproductions of paintings. Paul Klee was my favorite painter growing up, because of a print of Dance You Monster to My Soft Song! that hung in the lodge. It includes a simple, almost childlike line drawing of what looked to me like a young girl. She stands near the bottom of the picture, her hands moving as if she were conducting an orchestra, commanding the monster hovering above her into motion. I'd stand before this image and imagine that I was the girl.

My parents worked from morning till night, much more than an eight-hour day. I was rarely the center of attention. They often left me and Tatiana with nannies, or entirely on our own. That's how I got pneumonia for the first time—I woke up and they weren't home, and I tried to go find them. It amused my family that Tatiana was more attached to her older sister than to her own mother. Whenever they had to leave town, they would hand us over to friends of theirs, a woman I called Grandma Kubicka and her husband, who worked at the school as a steward. During the war, Grandma Kubicka had marched all the way from Siberia to Berlin as part of General Berling's army, carrying a gun and wearing riding boots. I admired her for it.

My parents and I did connect deeply around literature, which they both greatly respected. They'd recommend books to me, which was important. I have a theory that people who don't read much before the age of fourteen never fully develop areas in the brain that process text into images or experiences. If you become a serious reader only in college, you interpret everything analytically. I sometimes see this in academic critics—they're so intelligent, and yet something eludes them

Would you mind if I smoked a cigarette?

INTERVIEWER

Not at all. Were you a good student?

TOKARCZUK

I was at the absolute top of my class until fourth grade, when multiplication and division entered the picture. For the first time in my life, I hit a wall—I didn't get math, and several other kids were better at it. I think the experience was mildly traumatic for me, accustomed as I had been to intellectual omnipotence. As a result, I convinced myself that I wasn't into science—quite mistakenly, since it now seems to me that I have a scientific mind.

I recently reconnected with one of my primary school teachers, who tells me I was rather eccentric. Apparently, after finishing an assignment, I would ask, "May I nourish myself now?" Then I would pull out sandwiches and a soda bottle filled with milk and sit there eating, while the other children continued to work.

INTERVIEWER

What did you read when you were young?

TOKARCZUK

Early on, Tatiana and I discovered Jan Parandowski's classic Polish-language retellings of Greek and Roman myths. We must have gone through two or three copies of that book. I was obsessed, to the point of inventing my own gods of water and of trees. I intuitively sensed divine presences in nature, and Greek mythology helped me name and venerate them. Winds interested me the most—the direction they blew from, their names, their properties.

My mother had a lot of the Polish canon memorized. She'd urge me to read writers like Stefan Zeromski and Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz, but I wasn't very interested in Polish literature, in great part because that was her domain, I'm embarrassed to say. My father was an aspiring writer, and he subscribed to the monthly magazine Literatura na awiecie (Literature in the world)—that's how I had my encounter with Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Every summer we'd stay with my mother's parents, who ran a kind of guesthouse with a state library nearby, and it was there that my reading took on a frenzied, orgiastic quality. As a young teenager, I learned large portions of T. S. Eliot's poetry by heart, both in English and in Polish. A bilingual edition of his selected poems is the only book I've ever stolen from a library. Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom! bowled me over around the same time—for a while, no other writer seemed more important. Today, he strikes me as completely indigestible, but it was through The Sound and the Fury that I discovered stream-of-consciousness narration. In 1975, the first-ever translation of Beyond the Pleasure Principle came out in Polish. I was fifteen when I read it. Freud's ideas about how one could interpret the world—discovering hidden systems of meaning that explained our relations to our reality and to ourselves—made a huge impression on me. For one of my high school assignments, I tried to apply Freud's method to Absalom.

INTERVIEWER

Did you start writing very early?

TOKARCZUK

When I was twelve, I embarked on my first novel, which was about witches. They lived in the forest—a mother with four daughters, each with her own special spells and powers. But I never thought I would become a writer. I wanted to be a dancer, or to study nuclear physics or "medicine for space travel." It disappointed me to discover that the latter wasn't a thing. As a teenager, I published a few short pieces in the youth magazine Na przelaj (Off-Road). They were nervy, inconsistent stories about bizarre things—I was trying to imitate Jose Donoso and Julio CortAzar. The longest, "Piegn o psim powstaniu" (Canticles of the conquering canines), described an alternate reality in which dogs had taken over the world. Another was about the Polish

tradition of buying a live carp and keeping it alive in the bathtub for days, then murdering it in the tub on Christmas Eve—it's off the wall that our people do that. My father supported my writing wholeheartedly—so much so that he would type out my stories for me. I dictated them to him. It felt embarrassing to have someone listening to what I'd written, but he did it with a straight face.

In high school, my friends and I held meetings we called uposathas, the Sanskrit word for days of communal reflection and observance. I'd often bring in Buddhist scriptures I was reading at the time. Someone in our circle had access to British music, and we listened to records by Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple. I learned a lot from my first boyfriend, too—he introduced me to Bruno Schulz. He went on to study philosophy at Warsaw, and I followed him there to study psychology.

INTERVIEWER

How did you like school in Warsaw?

TOKARCZUK

I'd assumed that getting a degree in psychology would meaning more about psychoanalysis. But nobody taught psychoanalysisin the Polish People's Republic, and when I got there, I realized too late that I was in a deeply behaviorist department. I sat through a lot of lectures about rats and involuntary reflexes.

Warsaw itself traumatized me. I moved into a dorm on Zamenhof Street, and the capital's shops, theaters, and restaurants were overwhelming. When my boyfriend and I broke up, I felt completely abandoned. At the end of 1981, Poland fell into political crisis.

The world felt hopeless—I'd take the streetcar and see sad, tired people rushing around me with their plastic bags. It made me want to cry. I went into along period of melancholy. Everyone partied a lot, partly out of despair.

My sense of alienation was compounded by class disparity. I was a small-town girl, and psychology was an elite field of study in communist Poland—one of my fellow students vacationed in France, another would visit an aunt in Glasgow. In my second or third year, I began volunteering as a therapist at an outpatient clinic led by a group of American-trained humanistic psychologists. I underwent my first analysis with them—a form of group therapy—and I was assigned to a few patients. It was difficult work—these days, no one would let an inexperienced student treat disorders as serious as theirs.

INTERVIEWER

Who were your patients? Did you ever write about them?

TOKARCZUK

One was an unemployed man whom the neighborhood nicknamed Jag Partyzant—Johnny the Partisan. He must have been around forty, very traumatized, and he walked around dressed as a Second World War soldier, carrying messtins and holsters. He was intensely anxious.

Once, when I was calming him down in his apartment, I decided to try out a technique I'd learned in my training—leading him out of his delusions by entering them. He was telling me that someone had poisoned his water, that people were watching him from behind the tree branches and that tanks were in the streets, waiting to attack. "Let's have a look at the water," I said. "Granted, it's rusty, but that's because they've recently worked on the pipes. Since these repairs, though, it's become the best water in Warsaw, and there's no need to be afraid." I went on, "Look, there's nobody outside. Everything is fine." I still remember the glow of the streetlamps that evening as we both looked upon the snow through the window. After he felt better, I went back to my dorm and joined a party. In the morning, I discovered that martial law had been announced, and tanks were going to come out into the streets after all. That's the episode I describe in my short story "Che Guevara"—I owe that to Jag. At that time I was writing mostly poems—I was busy, and it felt faster than writing fiction. One poem, called "Oddzial psychogeriatryczny" (Psychogeriatric ward), was published in Mandragora magazine. Don't go looking for them— they're not very good.

Later in my career, I treated a young man with a complex family history that he recounted to me at length. A couple of years later, his younger brother became my patient and related the same events to me in my office. Their narratives couldn't have been more different. One described his mother as a cold bitch—pardon my language—and his father as the sole source of emotional support.The other told me that his mother was his savior in the face of his abusive father. It threw me into something of a vocational crisis. Was I supposed to drill down to some deep foundational trauma—say, a malevolent uncle—that would explain these discrepancies and repair their psyches? Experiences like that were what eventually pulled me away from psychoanalysis as an aspiring science.

INTERVIEWER

But you practiced as a psychotherapist for a time?

TOKARCZUK

Yes, for about five years. I met my first husband during a therapeutic training—I was leading the workshop, he was a mature student, and it was love at first sight. He'd inherited a family apartment in Walbrzych, a backwater mining town, so we moved there. I remember arriving and looking around at men in wifebeaters smoking and drinking beer on the doorsteps of dirty houses, and wondering what we'd done. I found a job working with alcoholics at a mental health clinic. My husband and I started a local version of AA, to help them quit. After my son was born, I would take the stroller with me to meetings. I also offered individual therapy, using a makeshift collage of clinical methods.

I burned out quickly. I started feeling stuck during sessions, wondering whether I was more disturbed and more in need of therapy than my patients. I realized I was caught between what I wanted to do for others and for myself. From childhood, I'd been taught that one ought to help people, and I chafed against it. I still own a book that left me shaken as a child, about a gnome who lives in a forest. He likes to hang out at home in solitude, writing or puttering about. Meanwhile, ants, grasshoppers, and so forth keep knocking on his door, asking for help. The gnome bristles at this— "Leave me alone, I have things to do," he shouts—and then cools off and helps the grasshopper, say, build a bridge. So it goes with all the other animals. Today, I remain torn between my desire for introverted independence and the obligation to help others. You can see that tension in my birth chart.

INTERVIEWER

What star sign are you?

TOKARCZUK

I'm an Aquarius—that's where the pro-social, curious part of my personality comes from—but Neptune is in Scorpio in my birth chart, in opposition to all that.

In any case, my husband and I turned to work that seemed more creative and educational—we started a support group for young teachers who were feeling overwhelmed, and meanwhile founded a publishing house called Unus, in 1991. In the group we did a lot of reenactments, playing out conflicts that had happened in class. Sometimes deep traumas bubbled up to the surface. Many teachers around Walbrzych still remember me from those workshops.

I had discovered Jung a couple of years earlier, and was taken with his idea of the collective unconscious, as well as with his insistence that we belong to the organic world—that plants, animals, and mushrooms are all important to understanding human consciousness. In my enthusiasm, I decided to put out a Polish translation of a critical dictionary of Jungian analysis—in Walbrzych, of all places. Jung wasn't known in Poland at the time—even years later, if ever I referred to Jung in my books, people would respond as though I were discussing astrology or palm reading. For the most part, we published manuals on group therapy and communication training. Eventually we also opened a bookstore. I worked there for about a year and had the most wonderful time. All these projects supported me until I became able to make a living as a novelist. I began to toy with quitting nonwriterly work only while I was working on Primeval and Other Times. With two and a half books under my belt, I thought maybe I had a chance.

INTERVIEWER

How did motherhood affect your work?

TOKARCZUK

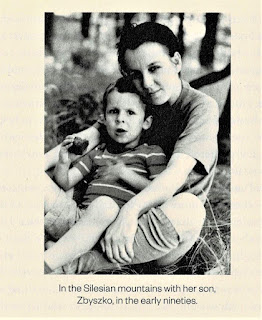

Having children young has its benefits—motherhood doesn't seem as extraordinary. A little person comes into your life and you befriend him. You have plenty of energy, so you can party late into the night and then get up in the morning to play and to go to the mountains together—it all seems natural. I followed my mother's example and got the whole family involved in raising

Zbyszko. My husband and I continued to work and travel. I don't feel that having a child hampered me or stopped me from living my life. Reading Beyond the Pleasure Principle felt more existentially transformative than becoming a mother.

INTERVIEWER

Were you political in the eighties and nineties?

TOKARCZUK

Wasn't everybody? In high school, I identified as an anarchist and then as a Maoist. I thought the Solidarity movement wasn't radical enough—I wanted total revolution. In Warsaw, as I got to know Solidarity better, their religiousness still bothered me—everything was entwined with the Pope, the Catholic Church, Mass, and prayer. I participated in the strikes with great conviction, but I wasn't an organizer. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, I knew that the world was changing, but working with alcoholics had exposed me to such human misery that I couldn't bring myself to be optimistic.

The main difference was that, before then, I'd made only brief excursions to East Germany, on our side of the Iron Curtain. As soon as it fell, I went to the UK to make some money.

INTERVIEWER

What changed for you in London?

TOKARCZUK

I had stopped writing for a few years while setting myself up as a psychotherapist, and I started again. In London, I visited a radical

Comments

Post a Comment