TOMAS TRASTROMER & MANDELTAM & OTHERS

In Damascus:

the traveler sings to himself:

I return from Syria

neither alive

nor dead

but as clouds

that ease

the butterfly's burden

from my fugitive soul

TRISTIA

There is, I

know, a science of separation

In night's

disheveled elegies, stifled laments,

The

clockwork oxen jaws, the tense anticipation

As the

city's vigil nears its sun and end.

I honor the

natural ritual of the rooster's cry,

The moment when,

red-eyed from weeping, sleepless

Once again,

someone hoists the journey's burden,

And to weep

and to sing become the same quicksilver verb.

But who can

prophesy in the word good-bye

The abyss of

loss into which we fall;

Or what, when

the dawn fires burn in the Acropolis,

The

rooster's rusty clamor means for us;

Or why, when

some new life floods the cut sky,

And the barn-warm

oxen slowly eat each instant,

The rooster,

harbinger of the one true life,

Beats his

blazing wings on the city wall?

I love the

calm and custom of quick fingers weaving,

The

shuttle's buzz and hum, the spindle's bees.

And look—arriving

or leaving, spun from down,

Some

barefoot Delia barely touching the ground . . .

What rot has

reached the very root of us

That we

should have no language for our praise?

What is,

was; what was, will be again; and our whole

Sweetness

lies in these meetings that wen recognize.

Soothsayer,

truth-sayer, morning's mortal girl,

Lose your gaze

again in the melting wax

That whitens

and tightens like the stretched pelt of a

squirrel

And find the

fates that will in time find us.

In clashes

of bronze, flashes of consciousness,

Men live,

called and pulled by a world of shades.

But women—all

fluent spirit; piercing, pliable eye—

Wax toward

one existence, and divining they die.

(1918)

TRISTIA

Il existe,

je sais, une science de la séparation

Dans les

élégies échevelées de la nuit, les lamentations étouffées,

Les

mâchoires des bœufs mécaniques, l'attente tendue

Alors que la

veillée de la ville approche de son soleil et de sa fin.

J'honore le

rituel naturel du cri du coq,

Le moment

où, les yeux rouges à force de pleurer, je ne dors pas

Une fois de

plus, quelqu'un soulève le fardeau du voyage,

Et pleurer

et chanter deviennent le même verbe vif-argent.

Mais qui

peut prophétiser avec le mot au revoir

L'abîme de

perte dans lequel nous tombons ;

Ou quoi,

quand les feux de l'aube brûlent sur l'Acropole,

La clameur

rouillée du coq signifie pour nous ;

Ou pourquoi,

quand une nouvelle vie inonde le ciel coupé,

Et les bœufs

chauds dans l'étable mangent lentement à chaque instant,

Le coq,

signe avant-coureur de la seule vraie vie,

Battre ses

ailes flamboyantes sur les remparts de la ville ?

J'aime le

calme et la coutume du tissage rapide des doigts,

Le

bourdonnement de la navette, les abeilles du fuseau.

Et regardez,

arrivant ou partant, filé du bas,

Une Delia

pieds nus touchant à peine le sol. . .

Quelle

pourriture a atteint nos racines

Que nous ne

devrions pas avoir de langage pour nos louanges ?

Ce qui est,

était ; ce qui était, sera à nouveau ; et notre tout

La douceur

réside dans ces rencontres que l'on se reconnaît.

Devin,

devin, mortelle du matin,

Perdez à

nouveau votre regard dans la cire fondante

Qui blanchit

et se resserre comme la peau tendue d'un

Écureuil

Et trouvez

les destins qui nous trouveront avec le temps.

Dans des

heurts de bronze, des éclairs de conscience,

Les hommes

vivent, appelés et tirés par un monde d’ombres.

Mais les

femmes — toutes ont un esprit fluide ; œil perçant et souple—

Cire vers

une seule existence, et devinant ils meurent.

(1918)

Devin,

devin, mortelle du matin,

Perdez à

nouveau votre regard dans la cire fondante

Qui blanchit

et se resserre comme la peau tendue d'un

écureuil

Et trouvez

les destins qui nous trouveront avec le temps.

Dans des

heurts de bronze, des éclairs de conscience,

Les hommes

vivent, appelés et tirés par un monde d’ombres.

Mais les

femmes — toutes ont un esprit fluide ; œil perçant et souple—

Cire vers

une seule existence, et devinant ils meurent.

(1918)

TRISTIA

Tôi biết có

một khoa học về sự tách biệt

Trong đêm

thanh lịch nhếch nhác, những lời than thở nghẹn ngào,

Hàm bò theo

kim đồng hồ, sự chờ đợi căng thẳng

Khi buổi cầu

nguyện của thành phố sắp đến gần và kết thúc.

Tôi tôn vinh

nghi thức tự nhiên của tiếng gà trống kêu,

Khoảnh khắc

mắt đỏ hoe vì khóc, mất ngủ

Một lần nữa,

có người nâng gánh nặng cuộc hành trình,

Và khóc và

hát trở thành cùng một động từ thủy ngân.

Nhưng ai có

thể nói tiên tri bằng lời từ biệt

Vực thẳm mất

mát mà chúng ta rơi vào;

Hay sao, khi

bình minh rực cháy ở Acropolis,

Tiếng kêu rỉ

sét của con gà trống có ý nghĩa đối với chúng ta;

Hoặc tại sao,

khi sự sống mới nào đó tràn ngập bầu trời cắt xén,

Còn bò ấm

chuồng từ từ ăn từng miếng,

Con gà trống,

điềm báo của một cuộc sống đích thực,

Đập đôi cánh

rực lửa của mình trên tường thành?

Tôi yêu sự

yên tĩnh và thói quen dệt ngón tay nhanh chóng,

Tiếng vo ve

của tàu con thoi, tiếng ong của trục quay.

Và nhìn

xem—đến hay đi, quay từ dưới xuống,

Một số Delia

chân trần gần như không chạm đất. . .

Cái thối nát

nào đã chạm tới tận gốc rễ của chúng ta

Rằng chúng

ta không có ngôn ngữ để khen ngợi?

Cái gì đã là;

những gì đã có, sẽ lại có; và toàn bộ của chúng tôi

Sự ngọt ngào

nằm trong những cuộc gặp gỡ mà chúng ta nhận ra.

Người xoa dịu,

người nói sự thật, cô gái phàm trần của buổi sáng,

Lại đánh mất

ánh nhìn của bạn trong lớp sáp tan chảy

Nó trắng lên

và săn chắc như tấm da căng ra của một con thú

con sóc

Và tìm ra số

phận sẽ tìm thấy chúng ta theo thời gian.

Trong những

cuộc đụng độ bằng đồng, những tia sáng của ý thức,

Đàn ông sống,

được kêu gọi và lôi kéo bởi một thế giới bóng tối.

Nhưng đàn bà

- tất cả đều có tinh thần trôi chảy; con mắt xuyên thấu, mềm mại—

Wax hướng tới

một sự tồn tại, và bói toán họ chết.

(1918)

Tristia: Sorrow

Leningrad

I've

returned to my city, it's familiar in truth

To the

tears, to the veins, swollen glands of my youth.

You are here once again, — quickly gulp in a trance

The fish oil

of Leningrad's riverside lamps.

Recognize

this December day from afar,

Where an egg

yolk is mixed with the sinister tar.

I'm not

willing yet, Petersburg, to perish in slumber:

It is you

who retains all my telephone numbers.

I have

plenty of addresses, Petersburg, yet,

Where I'm certain to find the voice of the dead.

In the dark

of the staircase, my temple is threshed

By the knocker ripped out along with the flesh.

All night

long, I await my dear guests like before

As I shuffle the shackles of the chains on the

door.

1930

Léningrad

Je suis

retourné dans ma ville, c'est familier en vérité

Aux larmes,

aux veines, aux ganglions gonflés de ma jeunesse.

Vous êtes là

une fois de plus, — avalez rapidement en transe

L'huile de

poisson des lampes au bord de la rivière de Léningrad.

Reconnaître

de loin ce jour de décembre,

Où un jaune

d’œuf se mêle au sinistre goudron.

Je ne veux

pas encore, Pétersbourg, périr dans le sommeil :

C'est vous

qui conservez tous mes numéros de téléphone.

J'ai encore

plein d'adresses, à Saint-Pétersbourg,

Où je suis

sûr de trouver la voix des morts.

Dans le noir

de l'escalier, ma tempe est battue

Par le

heurtoir arraché avec la chair.

Toute la

nuit, j'attends mes chers invités comme avant

Pendant que

je mélange les chaînes des chaînes sur la porte.

1930

Leningrad

Tôi đã trở lại

thành phố của mình, nó thực sự quen thuộc

Đến những giọt

nước mắt, đến những mạch máu, những tuyến sưng tấy của tuổi trẻ tôi.

Bạn lại ở

đây một lần nữa, - nhanh chóng nuốt nước bọt trong trạng thái thôi miên

Dầu cá của

những ngọn đèn ven sông ở Leningrad.

Nhận ra ngày

tháng mười hai này từ xa,

Nơi mà lòng

đỏ trứng được trộn với hắc ín.

Petersburg,

tôi chưa sẵn sàng chết trong giấc ngủ:

Chính bạn là

người giữ lại tất cả số điện thoại của tôi.

Tôi có rất

nhiều địa chỉ, Petersburg,

Nơi tôi chắc

chắn sẽ tìm thấy tiếng nói của người chết.

Trong bóng tối

của cầu thang, ngôi đền của tôi bị đập nát

Bởi tiếng gõ

cửa xé ra cùng với thịt.

Suốt đêm dài

đợi khách thân thương như xưa

Khi tôi xáo

trộn cùm xích trên cửa.

1930

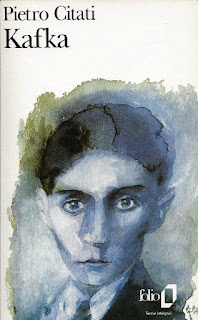

Osip

Mandelstam (1891-1938)

Osip

Emilievich Mandelstam was born in Warsaw to a Polish Jewish family; his father

was a leather merchant, his mother a piano teacher. Soon after Osip’s birth the

family moved to St Petersburg. After attending the prestigious Tenishev School,

Mandelstam studied for a year in Paris at the Sorbonne, and then for a year in

Germany at the University of Heidelberg. In 1911, wanting to enter St

Petersburg University — which had a quota on Jews — he converted to

Christianity; like many others who converted during these years, he chose

Methodism rather than Orthodoxy.

Under the

leadership of Nikolay Gumilyov, Mandelstam and several other young poets formed

a movement known first as the Poets' Guild and then as the Acmeists. Mandelstam

wrote a manifesto, 'The Morning of Acmeism’ (written in 1913, but published

only in 1919). Like Ezra Pound and the Imagists, the Acmeists valued clarity,

concision and craftsmanship.

In 1913

Mandelstam published his first collection, “Stone”. This includes several poems

about architecture, which would remain one of his central themes. A poem about

the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris ends with the declaration:

Fortress

Notre-Dame, the more attentively

I studied

your stupendous ribcage,

the more I

kept repeating: in time I too

will craft

beauty from sullen weight.

In its

acknowledgement of earthly gravity and its homage to the anonymous masons of

the past, the poem is typically Acmeist.

Mandelstam

was also a great love poet. Several women — each an important figure in her own

right — were crucial to his life and work. An affair with Marina Tsvetaeva

inspired many of his poems about Moscow. His friendship with Anna Akhmatova

helped him withstand the persecution he suffered during the 1930s. He had

intense affairs with the singer Olga Vaksel and the poet Maria Petrovykh. Most

important of all was Nadezhda Khazina, whom he married in 1922.

Osip and

Nadezhda Mandelstam moved to Moscow soon after this. Mandelstam's second book,

“Tristia”, published later in 1922, contains his most eloquent poetry; the tone

is similar to that of Yeats's 'Sailing to Byzantium' or some of Pound's first

“Cantos”. Several poems were inspired by the Crimea, where Mandelstam had

stayed as a guest of Maximilian Voloshin. Once a Greek colony, the Crimea was

for Mandelstam a link to the classical world he loved; above all, it granted

him a sense of kinship with Ovid, who had also lived by the Black Sea. It was

while exiled to what is now Romania that Ovid had composed his own “Tristia”.

The final

section of Mandelstam's 1928 volume “Poems” (the last collection he was able to

publish in his life) is titled 'Poems 1921-25'. These twenty poems differ from

any of his previous work. Many are unrhymed, and they are composed in lines and

stanzas of varying length. This formal disintegration reflects a sense of

crisis that Mandelstam expresses most clearly in 'The Age':

Buds will

swell just as in the past,

sprouts of

green will spurt and rage,

but your

backbone has been smashed,

my grand

and pitiful age.

And so,

with a meaningless smile,

you glance

back, cruel and weak,

like a

beast once quick and agile,

at the

prints of your own feet.

For several

years from 1925 Mandelstam abandoned poetry — or, as he saw it, was abandoned

by poetry. Alienated from himself and the world around him, he supported

himself by translating. He also wrote memoirs, literary criticism and

experimental prose.

What helped

Mandelstam to recover was a journey to Armenia from May to November 1930. The

self-doubt of 'Poems 1921-25' yields to an almost joyful acceptance of tragedy.

Armenia's importance to Mandelstam is not surprising: it is a country of stone,

and one of the arts in which Armenians have long excelled is architecture. And

to Mandelstam, Armenia represented the Hellenistic and Christian world where he

felt his roots lay; there are ruins of Hellenistic temples not far from Yerevan

and it was on Mount Ararat — which dominates the city's skyline — that Noah's

Ark is believed to have come to rest. Mandelstam drew strength from a world

that felt more solid, and more honest, than the Russia where he had become an

outcast.

In the

autumn of 1933 Mandelstam composed an epigram about Stalin, then read it aloud

at several small gatherings in Moscow. It ends:

Horseshoe-heavy,

he hurls his decrees low and high:

in the

groin, in the forehead, the eyebrow, the eye.

Executions

are what he likes best.

Broad is

the highlander's chest.

(trans.

Alexandra Berlina)

Six months

later Mandelstam was arrested. Instead of being shot, he was exiled to the

northern Urals; the probable reason for this relative leniency is that Stalin,

concerned about his own place in the history of Russian literature, took a

personal interest in Mandelstam's case. After Mandelstam attempted suicide, his

sentence was commuted to banishment from Russia's largest cities. Mandelstam

and his wife settled in Voronezh. There, sensing he did not have long to live,

Mandelstam wrote the poems that make up the three “Voronezh Notebooks”. Dense

with wordplay yet intensely lyrical, these are hard to translate. A leitmotif

of the second notebook is the syllable `os'. This means either 'axis' or 'of

wasps' — and it is the first syllable of both Mandelstam’s and Stalin's first

names ('Osip' and `Iosif are, to a Russian ear, just different spellings of a

single name). In the hope of saving his own life, Mandelstam was then composing

an Ode to Stalin; he evidently imagined an axis connecting himself — the great poet

— and Stalin — the great leader.

In May 1938

Mandelstam was arrested a second time and sentenced to five years in the Gulag.

He died in a transit camp near Vladivostok on 27 December 1938. His widow

Nadezhda preserved most of his unpublished work and also wrote two memoirs,

published in English as “Hope Against Hope” and “Hope Abandoned”.

Cautious,

toneless sound

of fruit

from a tree

to the

constant

melody of

forest silence . . .

(1908)

John Riley

*

From the

dimly lit hall

you slipped

out in a light shawl.

The

servants slept on,

we

disturbed no one . . .

(1908)

James

Greene

*

To read

only children's tales

and look

through a child's eye;

to rise

from grief and wave

big things

goodbye.

Life has

tired me to death;

life has no

more to offer.

But I love

my poor earth

since I

know no other.

I swung in

a faraway garden

on a plain

plank swing;

I remember

tall dark firs

in a

feverish blur.

(1908)

Robert

Chandler

Newly

reaped ears of early wheat

lie in

level rows;

fingertips

tremble, pressed against

fingers

fragile as themselves.

(1909)

James

Greene

“Silentium”

She has yet

to be born:

she is

music and word,

and she

eternally bonds

all life in

this world.

The sea

breathes gently;

the day

glitters wildly.

A bowl of

dazed azure

sways pale

foam-lilac.

May I too

reach back

to that

ancient silence,

like a note

of crystal

pure from

its source.

Stay,

Aphrodite, as foam.

Return,

word, to music.

Heart, be

shy of heart,

fused with

life's root.

(1910)

Robert

Chandler and Boris Dralyuk

No, not the

moon — the bright face of a clock

glimmers to

me. How is it my fault

that I

perceive the feeble stars as milky?

And I hate

Batyushkov’s unbounded arrogance:

What time

is it? someone simply asked —

and he

replied to them: “eternity”!

(1912)

Boris

Dralyuk

“The

Admiralty”

A dusty

poplar in the northern capital,

a

transparent clock face lost in the leaves;

and,

shining through this green — a brother

to both sky

and water — a frigate, an acropolis.

Aerial

craft, touch-me-not mast, straight edge

repeating

to Peter's heirs this golden rule:

beauty is

no demi-god's caprice

but a plain

carpenter’s rule, his raptor's eye.

Four

elements rule over us benignly;

free man is

able to create a fifth.

Doesn't

this ark, this chastely crafted ark

deny the

sovereignty of space?

Angry and

whimsical, the jellyfish cling on;

anchors lie

rusting like discarded ploughs —

we cast

away the chains of Euclid's space

and the

world's seas open before us.

(1913)

Robert

Chandler

Dombey and

Son

The

shrillness of the English language

and

Oliver's dejected look

have

merged: I see the youngster languish

among a

pile of office books.

Charles

Dickens — ask him; he will tell you

what was in

London long ago:

the city,

Dombey, assets' value,

the River

Thames's rusty flow.

'Mid rain

and tears and counted money,

Paul

Dombey's curly-headed son

cannot

believe that clerks are funny

and laughs

at neither joke nor pun.

The office

chairs are sorry splinters;

each broken

farthing put to use,

and numbers

swarm in springs and winters,

like bees

perniciously let loose.

Attorneys

study every letter;

in smoke

and stench they hone their stings,

and, from a

noose, the luckless debtor —

a piece of

bast — in silence swings.

His foes

enjoy their lawful robbing,

lost are

for him all earthly boons,

and lo! His

only daughter, sobbing,

embraces

checkered pantaloons.

(1913)

Anatoly

Libermann

“Concerning

the chorus in Euripides”

The

shuffling elders: a shambles

of sheep,

an abject throng!

I uncoil

like a snake,

my heart an

ancient ache

of dark

Judaic wrong.

But it will

not be long

before I

shake off sadness,

like a boy,

in the evening,

shaking

sand from his sandals.

(1914)

James

Greene

On the

black square of the Kremlin

the air is

drunk with mutiny.

A shaky

'peace' is rocked by rebels,

the poplars

puff seditiously.

The wax

faces of the cathedrals

and the

dense forest of the bells

tell us —

inside the stony rafters

a

tongueless brigand is concealed.

But inside

the sealed-up cathedrals

the air we

breathe is cool and dark,

as though a

Russian wine is coursing

through

Greece’s earthenware jars.

Assumption's

paradise of arches

soars up in

an astonished curve;

and now the

green Annunciation

awakens,

cooing like a dove.

The

Archangel and Resurrection

let in the

light like glowing palms —

everything

is secretly burning,

the jugs

are full of hidden flames.

(1916)

Thomas de

Waal

“Solominka”

I.

When you

lie there, Salome, in your vast

room, when

you can't sleep, when you lie and wait

for the

tall ceiling to descend, to brush

your

delicate eyelids with its grave weight; […]

when you

can’t sleep, things seem to gain in weight

or else are

lost — the silence is so full;

white

pillows glimmer palely in the glass;

the bed is

mirrored in a circling pool;

and pale

blue ice is streaming through the air.

Salome,

broken straw, you sipped at death,

drank all

of death, and only grew sweeter.

December

now streams out her solemn breath.

Twelve

moons are singing of the hour of death,

the room is

gone, the Neva takes its place,

Ligeia,

winter herself, flows through my blood,

and I have

learned to hear you, words of grace.

2..

Lenore,

Solominka, Ligeia, Seraphita.

The heavy

Neva fills the spacious room.

Salome, my

beloved straw, Solominka,

poisoned by

pity, slowly sips her doom.

And pale

blue blood runs streaming from the stone.

From all I

see only a river will remain.

Twelve

moons are singing of the hour of death.

And Salome

will never dance this dance again.

(1916)

Robert

Chandler

The thread

of golden honey flowed from the bottle

so heavy

and slow that our hostess had time to declare:

Here in

melancholy Tauris, where fate has brought us,

we are not

bored at all — and glanced back over her shoulder.

On all

sides the rites of Bacchus, as if the world

held only

watchmen and dogs, not a soul to be seen —

the days

roll peacefully by like heavy barrels:

away in the

hut are voices, you can't hear or reply.

We drank

tea, then went out to the huge brown garden,

dark blinds

were down like lashes over the eyes,

we walked

past the white columns to look at the vineyard

where the

somnolent hills are coated in airy glass.

I said: The

vines are alive like ancient battles,

where curly

horsemen are fighting in curving order,

in stony

Tauris the science of Hellas lives on —

and the

noble rusty array of golden acres.

And in the

white room quiet stands like a spinning wheel,

smells of

vinegar, paint and wine that is fresh from the cellar.

Remember,

in that Greek house, the much-loved wife —

not Helen —

the other wife — how long she embroidered?

Golden

fleece, oh where are you now, golden fleece?

All the

journey long the heavy sea waves were loud,

and leaving

his ship, his sails worn out by the seas,

full of

space and time, Odysseus came home.

(1917)

Peter

France

Heaviness,

tenderness — sisters — your marks are the same.

The wasps

and the honeybees suck at the heavy rose.

Man dies,

heat drains from the once warm sand,

and on a

black bier they carry off yesterday's sun.

Oh, you

tender nets and you heavy honeycombs,

easier to

lift a stone than to speak your name!

Only one

care is left to me in the world:

a care that

is golden, to shed the burden of time.

I drink the

mutinous air like some dark water.

Time is

turned up by the plough, and the rose was earth.

Slowly they

eddy, the heavy, the tender roses,

roses of

heaviness, tenderness, twofold wreath.

(1920)

Peter

France

Take from

my palms some sun to bring you joy

and take a

little honey — so the bees

of cold

Persephone commanded us.

No loosing

of the boat that is not moored,

no hearing

of the shadow shod in fur,

no

overcoming fear in life's dense wood.

And kisses

are all that's left us now,

kisses as

hairy as the little bees

who perish

if they fly out of the hive.

They rustle

in transparent depths of night,

their home

dense forests on Taigetos' slopes,

their food

is honeysuckle, mint and time.

So for your

joy receive my savage gift,

a dry and

homely necklace of dead bees

who have

transmuted honey into sun.

(1920)

Peter

France

*

I was

washing at night out in the yard,

the heavens

glowing with rough stars,

a star-beam

like salt upon an axe,

the water

butt cold and brim full.

A padlock

makes the gate secure,

and

conscience gives sternness to the earth —

hard to

find a standard anywhere

purer than

the truth of new-made cloth.

A star

melts in the water butt like salt,

cold water

in the butt is blacker still,

death is

pure, disaster saltier

and earth

more truthful and more terrible.

(1921,

Tbilisi)

Peter

France

“The

Horseshoe Finder (A Pindaric Fragment)”

We look at

a forest and say:

Here's a

forest for ships, for masts,

rose-shadowed

pines,

right to

their very tops free of shaggy burdens,

they ought

to creak in a windstorm,

like

solitary Italian pines,

in the

furious forestless air.

Beneath the

wind's salt heel the plumbline holds,

set in the

dancing deck,

and a

seafarer,

in his

insatiable thirst for space,

dragging

the brittle instrument of the geometer across

sodden

ruts,

collates

against the pull of earthly breast

the ragged

surface of seas.

But

drinking the scent

of resinous

tears, which show through the ship's planking,

admiring

the timber,

riveted,

well-jointed into bulkheads,

not by that

quiet carpenter of Bethlehem, but another —

the father

of voyages, the seafarer's friend —

we say:

They too

once stood on land,

ungainly,

like a donkey's spine,

their tops

overlooking their roots,

upon the

ridge of some renowned mountain,

and

clattered beneath fresh cloudbursts,

suggesting

vainly that the heavens exchange their noble burden

for a pinch

of salt.

Where shall

we start?

Everything

cracks and reels.

The air

shivers with similes.

One word’s

no better than another,

the earth

drones with metaphors,

and

lightweight carts

harnessed

garishly to flocks of birds dense with strain

burst to

pieces,

competing

with the snorting favourites of the hippodrome.

Thrice

blessed, he who guides a name into song;

the song

adorned with nomination

lives

longer among the others —

she's

marked among her friends by a fillet on her brow,

which saves

her from fainting, from powerful stupefying smells,

whether it

be the closeness of a man,

or the

smell of fur from a powerful beast,

or merely

the scent of savory, crushed between palms.

The air

grows dark, like water, and all things living swim

through it

like fish,

fins

thrusting aside the sphere,

compact,

resilient, barely warm, —

a crystal,

in which wheels spin and horses shy,

damp humus

of Neaira, furrowed anew each night,

by

pitchforks, tridents, hoes, and ploughs.

The air is

mixed as solidly as the earth:

one can't

get out of it, to enter it is difficult.

A rustle

runs along the trees like some green ball.

Children

play at knucklebones with vertebrae of dead animals.

The fragile

chronology of our era is drawing to its close.

Thanks for

everything that was:

I made

mistakes myself, fell astray, botched my reckoning.

The era

rang, like a golden sphere,

hollow,

molded, sustained by no one,

at every

touch responding 'Yes' or 'No'.

It answered

like a child:

'I'll give

you an apple' or 'I won't give you an apple',

its face a

perfect copy of the voice that speaks these words.

The sound’s

still ringing, though the source of sound has

vanished.

A horse

slumps in the dust and snorts in a lather,

but the

sharp turn of its neck

still keeps

the memory of racing forward with its out-flung

hooves —

when there

weren't only four of them,

but

numerous as stones upon the road,

rekindled

in four shifts,

as numerous

as the ground-beats of the blazing horse.

So,

the finder

of a horseshoe

blows off

the dust

and

burnishes it with wool, until it shines.

Then

he hangs it

over the threshold,

to take a

rest,

so it no

longer needs to strike out sparks from flint.

Human lips,

for which

there's nothing more to say,

retain the

form of their last-spoken word,

and weight

continues tangible in the hand

although

the jug,

spilled

half

while

carried home.

What I'm

saying now, I do not say,

but has

been dug from the earth, like grains of petrified wheat.

Some

portray a

lion on their coins,

others —

a head.

Assorted

copper, gold and bronze lozenges

lie with

equal honour in the earth.

The age,

which tried to gnaw them through, imprinted teeth

on them.

Time

lacerates me, like a coin,

and I'm no

longer ample for myself.

(1923,

Moscow)

Steven J.

Willett

“Armenia”

“Here

labour is understood

as an

awesome, six-winged bull;

and,

swollen with venous blood,

pre-winter

roses bloom.”

I.

You rock

the rose of Hafez

and dandle

your wild-beast children;

your lungs

are the octahedral shoulders

of

bull-like peasant churches."

Coloured in

raucous ochre,

you lie far

beyond the Mountain;"

here we

have only a picture,

a water

transfer peeled from a saucer.

2.

Oh, I can't

see a thing and my poor ear's gone deaf,

and there

are no colours left but red lead and this raucous ochre.

And

somehow, I found myself dreaming of an Armenian

morning,

I felt like

seeing how a tomtit gets by in Yerevan,

how a baker

plays at blind man's buff with the bread,

stooping to

scoop the moist warm hides from the oven . . .

Oh,

Yerevan, Yerevan! Were you sketched by a bird?

Or did a

lion colour you in, like a child with a box of crayons?

Oh,

Yerevan, Yerevan! More a roast nut than a city,

how I love

the Babels and Babylons of your big-mouthed streets.

I've

fingered and mauled my life, like a mullah his Koran,

I have

frozen my time, never spilt hot blood.

Oh,

Yerevan, Yerevan! There's nothing more that I need —

I don't

want your frozen grapes!

3.

You longed

for a dash of colour —

so a lion

who could draw

made a long

paw

and

snatched five or six crayons from a box."

Country of

blazing dyes

and dead

earthenware plains,

amid your

stones and clays

you endured

sultans and red-bearded sardars."

Far from

anchors and tridents,

where a

continent withers to rest,

you put up

with those ever-so-potent

potentates

who loved executions.

Simple as a

child's drawing,

not

stirring my blood,

your women

pass by, bestowing

gifts of

their graceful lionhood.

How I love

your ominous tongue,

your young

coffins,

where each

letter's a blacksmith's tong

and each

word a cramp-iron.

4.

Covering

your mouth like a moist rose,

octahedral

honeycombs in your hands,

all the

dawn of days you stood

on a

world's edge, swallowing your tears.

You turned

away in shame and sorrow

from the

bearded cities of the East —

and now you

lie amid clays and dyes

as they

take your death mask.

5.

Wrap your

hand in a kerchief

and plunge

it, through the celluloid thorns,

into the

heart of the wreath-bearing briar.

Snap.

Who needs

scissors?

But mind it

doesn't just fall apart-

scraps of

pink, confetti, a petal of Solomon,

a wildling

without oil or scent,

no use even

for sherbert.

6.

Realm of

clamouring stones —

Armenia,

Armenia!

summoning

the raucous mountains to arms —

Armenia,

Armenia!

Soaring

forever towards the silver trumpets of Asia" —

Armenia,

Armenia!

Lavishly

flinging down the Persian coins of the sun —

Armenia,

Armenia!

7.

No, not

ruins but what remains of a round and mighty forest,

anchor-stumps

of felled oaks from a Christianity of beasts

and fables,

capitals

bearing rolls of stone cloth, like loot from a heathen

marketplace,

grapes each

the size of a pigeon's egg, scrolls of eddying

rams'

horns,

and ruffled

eagles with the wings of owls, still undefiled by

Byzantium."

8.

The rose is

cold in the snow:

which lies

three fathoms deep on Sevan .

The

mountain fisherman has made off with his azure sledge

and the

whiskered snouts of stout trout

police the

lime-covered lake bed.

While in

Yerevan and Echmiadzin

the vast

mountain has drunk all the air.

I need to

entice it with an ocarina,

tame it

with a pipe

till the

snow melts in my mouth.

Snow, snow,

snow on rice paper,

the

mountain swims towards my lips.

I'm cold.

I'm glad.. .

9.

Clip clop

against purple granite,

a peasant's

horse stumbles

as it

mounts the bald plinth

of the

realm's sovereign stone,

while some

breathless Kurds run behind

with

bundles of cheese wrapped in cloth —

peacemakers

between God and the Devil

and backers

of both.

10.

What luxury

in an indigent village —

The

thread-like music of the water!

What is it?

Someone spinning? Fate? An omen?

Don't come

too close. There's trouble on the way.

And the

maze of the moist tune

conceals

something dark, stifling, whirring —

as if a

water nymph were paying a visit

to a

subterranean watchsmith.

II.

Clay and

azure. ... azure, clay . . .

What more

do you want? Just squint,

like a

myopic shah over a turquoise ring,

over a book

of ringing clays, a bookish earth,

a festering

text, a precious clay,

that hurts

us like music,

like the

word.

12. . .

I shall

never see you again,

myopic

Armenian sky;

never again

screw up my eyes

at Mount

Ararat’s nomad tent;

and in the

library of earthenware authors

I shall

never again open

the hollow

volume of a splendid land

that primed

the first people.

(1930,

Tbilisi)

Robert

Chandler

Help me, O

Lord, through this night.

I fear for

life, your slave.

To live in

Peter's city is to sleep in a grave.

(1931)

Robert

Chandler

After

midnight, clean out of your hands,

the heart

seizes a sliver of silence.

It lives on

the quiet, it's longing to play;

like it or

not, there's nothing quite like it.

Like it or

not, it can never be grasped;

so why

shiver, like a child off the street,

if after

midnight the heart holds a feast,

silently

savouring a silvery mouse?

(1931)

- Robert

Chandler

Gotta keep

living, though I've died twice,

and water's

driving the city crazy:

how

beautiful, what high cheekbones, how happy,

how sweet

the fat earth to the plough,

how the

steppe extends in an April upheaval,

and the

sky, the sky — pure Michelangelo . . .

(1935)

Andrew

Davis

Drawing the

youthful Goethe to their breast,

those Roman

nights took on the weight of gold.

I've much

to answer for, yet still am graced;

an outlawed

life has depths yet to be told.

(1935)

Robert

Chandler

*

Goldfinch,

friend, I'll cock my head —

let's check

the world out, just me and you:

this

winter's day pricks like chaff;

does it

sting your eyes too?

Boat-tailed,

feathers yellow-black,

sopped in

colour beneath your beak,

do you get,

you goldfinch you,

just how

you flaunt it?

What's he

thinking, little airhead? —

white and

yellow, black and red!

Both eyes

check both ways — both! —

will check

no more — he's bolted!

(1936)

Andrew

Davis

Deep in the

mountain the idol rests

in sweet

repose, infinite and blest,

the fat of

necklaces dripping from his neck

protects

his dreams of flood tide and of slack.

As a boy,

he buddied with a peacock,

they gave

him rainbow of India to eat

and milk in

a pink clay dish,

and didn't

stint the cochineal.

Bone put to

bed, locked in a knot,

shoulders,

arms and knees made flesh,

he smiles

with his own dead-silent lips,

thinks with

his bone, feels with his brow,

and

struggles to recall his human countenance.

(1936)

Andrew

Davis

You're not

alone. You haven't died,

while you

still, beggar-woman at your side,

take

pleasure in the grandeur of the plain,

the gloom,

the cold, the whirlwinds of snow.

In

sumptuous penury, in mighty poverty

live

comforted and at rest —

your days

and nights are blest,

your

sweet-voiced labour without sin.

Unhappy he,

a shadow of himself,

whom a bark

astounds and the wind mows down,

and to be

pitied he, more dead than alive,

who begs

handouts from a ghost.

(1937)

Andrew

Davis

Where can I

hide in this January?

Wide-open

city with a mad death-grip . . .

Can I be

drunk from sealed doors? —

I want to

bellow from locks and knots . . .

And the

socks of barking back roads,

and the

hovels on twisted streets —

and

deadbeats hurry into corners

and

hurriedly dart back out again . . .

And into

the pit, into the warty dark

I slide,

into waterworks of ice,

and I

stumble, I eat dead air,

and fevered

crows exploding everywhere —

But I cry

after them, shouting at

some

wickerwork of frozen wood:

A reader! A

councillor! A doctor!

A

conversation on the spiny stair!

(1937)

Andrew

Davis

Breaks in

round bays, and shingle, and blue,

and a slow

sail continued by a cloud —

I hardly

knew you; I've been torn from you:

longer than

organ fugues — the sea's bitter grasses,

fake

tresses — and their long lie stinks,

my head

swims with iron tenderness,

the rust

gnaws bit by bit the sloping bank .. .

On what new

sands does my head sink?

You,

guttural Urals, broad-shouldered Volga lands,

or this

dead-flat plain — here are all my rights,

and,

full-lunged, gotta go on breathing them.

(1937)

Andrew

Davis

Armed with

wasp-vision, with the vision of wasps

that suck,

suck, suck the earth's axis,

I’m filled

by the whole deep vein of my life

and hold it

here in my heart

and in

vain.

And I don't

draw, don't sing,

don't draw

a black-voiced bow over strings:

I only

drink, drink, drink in life and I love

to envy

wasp-

waisted

wasps their mighty cunning.

O if I too

could be

impelled past sleep, past death,

stung by

the summer’s cheer and chir,

by this new

air

to hear

earth's axis, axis, axis.

(1937)

Robert

Chandler

I'll say

this in a whisper, in draft,

because

it’s early yet:

we have to

pay

with

experience and sweat

to learn

the sky's free play.

And under

purgatory’s temporal sky

we easily

forget:

the dome of

heaven

is a home

to praise

forever, wherever.

(1937)

Robert

Chandler

The Penguin

Book of Russian Poetry

Silentium

Be silent, hide away and let

your thoughts and longings rise and set

in the deep places of your heart.

Let dreams move silently as stars,

in wonder more than you can tell.

Let them fulfil you — and be still.

What heart can ever speak its mind?

How can some other understand?

the hidden pole that turns your life?

A thought, once spoken, is a lie.

Don't cloud the water in your well;

drink from this wellspring — and be still.

Live in yourself. There is a whole

deep world of being in your soul,

burdened with mystery and thought.

The noise outside will snuff it out.

Day's clear light can break the spell.

Hear your own singing — and be still.

(1829--early

Silentium: A variation on Tyutchev's earlier poem

'Silentium’

(see page 105).

Chandler

Comments

Post a Comment