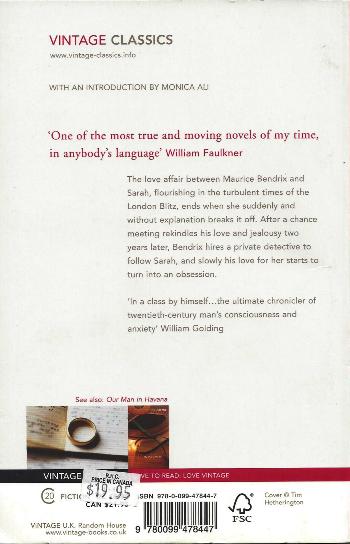

GG: Ways of Escape

Death in rue Catinat

Go and try

to disprove death, death will disprove you.

- TURGENEV

On 5 January

1952 the New York Times

reported that General de Lattre had been operated on in

Paris: 'Neither the nature of his illness nor of the operation has been

disclosed.' By 11 January the heroic soldier was dead; it was a time of

mourning in Vietnam, as a letter sent home by Nancy Baker shows:

For

about 4

weeks the latter part of January and the first of February, the local

French

and Vietnamese officials and the Diplomatic Corps were in

mourning for the

death of de Lattre. Not that I

was in agreement for that long length of time of mourning, we still had

a very

enjoyable time staying home in the evenings, reading, or have small

dinners.'

With de

Lattre gone, hope died that the French could win the war in Vietnam.

The United

States and France held opposed views on the country's future, and if

the US

State Department did not press France hard

this was only because it felt that France might throw in the towel, to

stem the

loss of its best sons. There were real divisions in the American

legation in

Saigon also. On the one hand Ambassador Heath was a genuine supporter

of the

French leadership symbolized by de Lattre. Edmund Gullion thought the

French

were wrong and that they were not serious about independence. He and

Robert Blum

were strongly against the survival of colonialism and in favor of

building up a

nationalist army. They both advocated ways of winning the war which the

French

authorities found unacceptable.

Blum, like Pyle in The Quiet American, was looking for a third force to capture the nationalist interest of the Vietnamese people. He felt that only if the Vietnamese were fighting for democracy and independence would they begin to take a powerful personal interest in defeating the communist Vietminh. Without a third force, he and Gullion both believed the French could not succeed. As Blum said:

Blum, like Pyle in The Quiet American, was looking for a third force to capture the nationalist interest of the Vietnamese people. He felt that only if the Vietnamese were fighting for democracy and independence would they begin to take a powerful personal interest in defeating the communist Vietminh. Without a third force, he and Gullion both believed the French could not succeed. As Blum said:

We

wanted to

strengthen the ability of the French to protect the area against

Communist

infiltration and invasion, and we wanted to capture the nationalist

movement

from the Communists by encouraging the national aspirations of the

local populations

and increasing popular support of their governments. We knew that the

French

were unpopular! that the war that had been going on since I946 was not

only nationalist

revolt against them but was an example of the awakening

self-consciousness of

the peoples of Asia who were trying to break loose from domination by

the Western

world.

Blum wanted

the United States to be looked upon as a friend to a new nation, not as

a

supporter of colonialism (that was an anathema to the Americans). After

visiting

Vietnam in I951, Congressman John F. Kennedy went home to preach the

gospel of

those forward-looking Americans in the legation. Speaking of how

America had

allied itself to the desperate effort of the French regime to hang on

to the

remnants of an empire, Kennedy concluded: 'the French cannot succeed in

Indochina

without giving concessions necessary to make the native army a reliable

and

crusading force. ' Emperor Bao

Dai feared that if the Vietnamese army were expanded into a nationalist

army,

it might defect en masse to the Vietminh. His tragedy

was that he was expressing

a truth that initially looked like cynicism.

Because Bao Dai proved so disappointing the Americans felt they had to find someone who represented the new nationalism, someone who opposed the French, someone without the taint of colonialist power, who was also strongly opposed to the communist Vietminh. Thus Colonel The became significant.

At the time that Greene was visiting Vietnam and beginning to writeThe Quiet American, Colonel The had not yet become important to the Americans. They knew he was small beer, but in the early days of his revolt from the Cao Dai his statements expressed his opposition to both the French and the communists. It was only later, after Dien Bien Phu in 1954 when the French were in the process of leaving Vietnam, that the Americans decided on their third force figure - the Catholic strong man Ngo Dinh Diem, who had spent much of the war in a monastery in New Jersey. Thé then came into his own by joining forces with Diem. He was brought back out of the jungle to support Diem by Colonel Lansdale with the help of CIA money. To the French The was a murderous reptile: to the ordinary Vietnamese a romantic hero.

Norman

Sherry: The Life of Graham Greene Volume

2: 39-55Because Bao Dai proved so disappointing the Americans felt they had to find someone who represented the new nationalism, someone who opposed the French, someone without the taint of colonialist power, who was also strongly opposed to the communist Vietminh. Thus Colonel The became significant.

At the time that Greene was visiting Vietnam and beginning to writeThe Quiet American, Colonel The had not yet become important to the Americans. They knew he was small beer, but in the early days of his revolt from the Cao Dai his statements expressed his opposition to both the French and the communists. It was only later, after Dien Bien Phu in 1954 when the French were in the process of leaving Vietnam, that the Americans decided on their third force figure - the Catholic strong man Ngo Dinh Diem, who had spent much of the war in a monastery in New Jersey. Thé then came into his own by joining forces with Diem. He was brought back out of the jungle to support Diem by Colonel Lansdale with the help of CIA money. To the French The was a murderous reptile: to the ordinary Vietnamese a romantic hero.

Ngô Đình Diệm

mang trong ông huyền thoại về một con người Mít hoàn toàn Mít, không

đảng phái,

không Đệ Tam, Đệ Tứ, không Việt gian bán nước cho Tây, cho Tầu, cho

Liên Xô.

Cùng với huyền thoại về một vĩ nhân Mít hoàn toàn Mít đó, là huyền

thoại về một

lực lượng thứ ba, như Gấu đã từng lèm bèm nhiều lần, đây là đề tài của

cuốn Người

Mỹ Trầm Lặng của Greene. Fowles khuyên anh chàng Mẽo ngây thơ, trầm

lặng, mang

Phượng về Mẽo, quên mẹ nó lực lượng thứ ba đi: lịch sử diễn ra đúng như

vậy, nước

Mẽo đã dang tay đón bao nhiêu con người Miền Nam bị cả hai bên bỏ rơi,

những cô

Phượng ngày nào. (1)

Trong "Tiểu sử

của Graham Greene", Tập 3, có cái tiểu chú, về lần GG phỏng vấn Tổng

Thống Diệm [bài phỏng vấn thấy ghi, ở cuối sách, 16.8.1982, đúng sinh nhật GCC, nhưng phỏng vấn Diệm ngày

nào, không], ông có hỏi Diệm là tại sao cho Thế

trở về,

khi ông ta trách nhiệm về vụ giết rất nhiều người của chính ông ta [ám

chỉ vụ

Thế chủ mưu giết thường dân tại Catinat] Greene nhớ là, Diệm bật cười

lớn, và nói:

“Peut-être, peut-être” [Có thể, có thể].

Cả cuốn "Người

Mỹ Trầm Lặng" xoay quanh nhân vật Thế, “Lực lượng thứ ba”, không có Thế

[LLTB] là

không có nó. Chúng ta tự hỏi, liệu có LLTB?

Because Bao

Dai proved so disappointing the Americans felt they had to find someone

who

represented the new nationalism, someone who opposed the French,

someone

without the taint of colonialist power, who was also strongly opposed

to the

communist Vietminh. Thus Colonel The became significant. At the time

that

Greene was visiting Vietnam and beginning to write The Quiet American,

Colonel

The had not yet become important to the Americans. They knew he was

small beer,

but in the early days of his revolt from the Cao Dai his statements

expressed his

opposition to both the French and the communists. It was only later,

after Dien

Bien Phu in 1954 when the French were in the process of leaving

Vietnam, that

the Americans decided on their third force figure - the Catholic strong

man

Ngo Dinh Diem, who had spent much of the war in a monastery in New

Jersey. Thé

then came into his own by joining forces with Diem. He was brought back

out of

the jungle to support Diem by Colonel Lansdale with the help of CIA

money. To

the French The was a murderous reptile: to the ordinary Vietnamese a

romantic

hero. Howard Simpson, an American writer in Saigon, described

overhearing an

'incongruous melodrama' (his words) involving General Nguyen Van Vy, a

pro-French

Bao Dai loyalist and chief of staff of the Vietnamese army, and Colonel

The:

Cao Dai

general Trinh Minh The, in civilian clothes, is lecturing Vy while

armed

members of The's newly formed pro-Diem 'Revolutionary Committee' have

taken up

positions by the doors and windows...

General Vy is being asked to read a prepared statement calling for an end to French interference in Vietnamese affairs, repudiating Bao Dai, and pledging his loyalty to Ngo Dinh Diem. Vy is responding to The's harangue in a low voice, trying to argue his case. The veins on The's forehead are standing out ... Suddenly The pulls a Colt .45 from his belt, strides forward, and puts its muzzle to Vy's temple. The pushes Vy to the microphone, the heavy automatic pressed tight against the general's short-cropped gray hair. I wince, waiting for the Colt's hammer to fall.

The repetitive clicking of a camera is the only sound in the tense silence ... Vy begins to read the text into the mike, the paper shaking in his hands. His face is ashen, and perspiration stains his collar. The complains he can't hear and demands that Vy speak louder. When Vy finishes, The puts his automatic away. General relief sweeps the room."

*

General Vy is being asked to read a prepared statement calling for an end to French interference in Vietnamese affairs, repudiating Bao Dai, and pledging his loyalty to Ngo Dinh Diem. Vy is responding to The's harangue in a low voice, trying to argue his case. The veins on The's forehead are standing out ... Suddenly The pulls a Colt .45 from his belt, strides forward, and puts its muzzle to Vy's temple. The pushes Vy to the microphone, the heavy automatic pressed tight against the general's short-cropped gray hair. I wince, waiting for the Colt's hammer to fall.

The repetitive clicking of a camera is the only sound in the tense silence ... Vy begins to read the text into the mike, the paper shaking in his hands. His face is ashen, and perspiration stains his collar. The complains he can't hear and demands that Vy speak louder. When Vy finishes, The puts his automatic away. General relief sweeps the room."

*

The's

influence is central to the plot of The

Quiet American. He is the

catalyst who reveals Pyle's 'special

duties” '.

The's desperate actions in the novel are based on historical fact.

Greene also

asserts, both in the novel and in his non-fictional writing, that the

CIA was

involved with The, providing him with the material to carry out

nefarious actions.

This is what so scandalized Liebling in the New Yorker: 'There is a

difference

. . . between calling your over-successful offshoot a silly ass and

accusing

him of murder.’

In his

dedication to Rene Berval and Phuong, Greene mentioned that he had

rearranged

historical events: 'the big bomb near the Continental preceded and did

not

follow the bicycle bombs. I have no scruples about such small

changes.'

Trong cuốn

tiểu sử của Greene, thì “Lực Lượng Thứ Ba”, anh Xịa ngây thơ gặp, là

Trình Minh

Thế. Greene không ưa TMT, và không tin ông làm được trò gì. Nhưng chỉ

đến khi

TMT bị Diệm thịt, thì ông mới thay đổi thái độ, như trong cái thư mở ra

"Người Mỹ

Trầm Lặng" cho thấy.

Theo GCC, cuốn NMTL được

phát sinh, là từ cái tên Phượng, đúng như

trong tiềm

thức của Greene mách bảo ông. (1)

Cả cuốn truyện là từ đó mà ra. Và nó còn tiên tri ra được cuộc xuất cảng người phụ nữ Mít cả trước và sau cuộc chiến, đúng như lời anh ký giả Hồng Mao ghiền khuyên Pyle, mi hãy quên “lực lượng thứ ba” và đem Phượng về Mẽo, quên cha luôn cái xứ sở khốn kiếp Mít này đi!

Cả cuốn truyện là từ đó mà ra. Và nó còn tiên tri ra được cuộc xuất cảng người phụ nữ Mít cả trước và sau cuộc chiến, đúng như lời anh ký giả Hồng Mao ghiền khuyên Pyle, mi hãy quên “lực lượng thứ ba” và đem Phượng về Mẽo, quên cha luôn cái xứ sở khốn kiếp Mít này đi!

The Life of

Graham Greene

Volume 2: 1939-1955

Norman Sherry

Volume 2: 1939-1955

Norman Sherry

Note: Một

trong những em Phượng, đi đúng những ngày 30 Tháng Tư, 1975, và là 1

trong những

nhà văn nữ hàng đầu của Miền Nam trước 1975, khi Gấu tới trại tị nạn,

gửi thư cầu

cứu, đã than giùm, anh đi trễ quá, Miền Biển Động hết động rồi.

Sao không ở

luôn với số phận xứ Mít [ở với VC?], chắc em P. của 1 anh Mẽo Pyle nào

đó, tính khuyên Gấu?

(1)

"Phuong,"

I said – which means Phoenix, but nothing nowadays is fabulous and

nothing

rises from its ashes. "Phượng", tôi nói, "Phượng có nghĩa là Phượng

hoàng, nhưng những ngày này chẳng có chi là huyền hoặc, và chẳng có gì

tái sinh

từ mớ tro than của loài chim đó":

Quả có sự

tái sinh từ mớ tro than của loài chim đó! Cuộc xuất cảng Phượng sau 1975, là cả 1 cái nguồn nuôi nước Mít, theo nghĩa thê thảm nhất, hoặc, cao cả nhất [Hãy nghĩ đến những gia đình Miền Nam phải cho con gái đi làm dâu Đại Hàn, thí dụ, để sống sót VC]

Kevin

Ruane, The

Hidden

History of Graham Greene’s Vietnam War: Fact, Fiction and The Quiet

American, History,

The Journal of the Historical Association, ấn hành bởi Blackwell

Publishing

Ltd., tại Oxford, UK và Malden, MA., USA, 2012, các trang 431-452.

LỊCH SỬ ẨN

TÀNG CỦA CHIẾN TRANH VIỆT NAM CỦA GRAHAM GREENE:

SỰ KIỆN, HƯ CẤU VÀ QUYỂN THE QUIET AMERICAN (NGƯỜI MỸ TRẦM LẶNG)

SỰ KIỆN, HƯ CẤU VÀ QUYỂN THE QUIET AMERICAN (NGƯỜI MỸ TRẦM LẶNG)

Ngô Bắc dịch

ĐẠI Ý:

Nơi

trang có minh họa đằng trước trang nhan đề của quyển tiểu

thuyết đặt khung cảnh tại Việt Nam của mình, quyển The Quiet

American,

xuất bản năm 1955, Graham Greene đã nhấn mạnh rằng ông viết “một truyện

chứ

không phải một mảnh lịch sử”, song vô số các độc giả trong các thập

niên kế

tiếp đã không đếm xỉa đến các lời cảnh giác này và đã khoác cho tác

phẩm sự

chân thực của lịch sử. Bởi viết ở ngôi thứ nhất, và bởi việc gồm

cả sự

tường thuật trực tiếp (được rút ra từ nhiều cuộc thăm viếng của ông tại

Đông

Dương trong thập niên 1950) nhiều hơn những gì có thể được tìm thấy

trong bất

kỳ tiểu thuyết nào khác của ông, Greene đã ước lượng thấp tầm mức theo

đó giới

độc giả của ông sẽ lẫn lộn giữa sự thực và hư cấu. Greene đã

không chủ

định để quyển tiểu thuyết của ông có chức năng như sử ký, nhưng đây là

điều đã

xảy ra. Khi đó, làm sao mà nó đã được ngắm nhìn như lịch sử? Để

trả lời

câu hỏi này, phần lớn các nhà bình luận quan tâm đến việc xác định

nguồn khởi

hứng trong đời sống thực tế cho nhân vật Alden Pyle, người Mỹ trầm lặng

trong

nhan đề của quyển truyện, kẻ đã một cách bí mật (và tai họa) phát triển

một Lực

Lượng Thứ Ba tại Việt Nam, vừa cách biệt với phe thực dân Pháp và phe

Việt Minh

do cộng sản cầm đầu. Trong bài viết này, tiêu điểm ít nhắm vào

các nhân

vật cho bằng việc liệu người Mỹ có thực sự bí mật tài trợ và trang bị

vũ khí

cho một Lực Lượng Thứ Ba hay không. Ngoài ra, sử dụng các thư tín

và nhật

ký không được ấn hành của Greene cũng như các tài liệu của Bộ Ngoại Vụ

[Anh

Quốc] mới được giải mật gần đây chiếu theo Đạo Luật Tự Do Thông Tin Của

Vương

Quốc Thống Nhất (UK Freedom of Information Act), điều sẽ được nhìn thấy

rằng

người Anh cũng thế, đã có can dự vào mưu đồ Lực Lượng Thứ Ba sau lưng

người

Pháp và rằng bản thân Greene đã là một thành phần của loại dính líu

chằng chịt

thường được tìm thấy quá nhiều trong các tình tiết của các tiểu thuyết

của ông.

Note: Nguồn

của bài viết này, đa số lấy từ “Ways of Escape” của Graham Greene.

Và cái sự lầm lẫn giữa giả tưởng và lịch sử, ở đây, là do GG cố tình, như chính ông viết:

Và cái sự lầm lẫn giữa giả tưởng và lịch sử, ở đây, là do GG cố tình, như chính ông viết:

Như vậy là đề tài Người Mỹ

Trầm Lặng đến với tôi, trong

cuộc “chat”, về “lực lượng thứ ba” trên con đường đồng bằng [Nam Bộ] và

những

nhân vật của tôi bèn lẵng nhẵng đi theo, tất cả, trừ 1 trong số họ, là

từ tiềm

thức. Ngoại lệ, là Granger, tay ký giả Mẽo. Cuộc họp báo ở Hà Nội, có

anh ta,

được ghi lại, gần như từng lời, từ nhật ký của tôi, vào thời kỳ đó.

Có lẽ cái chất phóng sự của Người

Mỹ Trầm Lặng nặng “đô” hơn, so với bất

cứ cuốn tiểu thuyết nào mà tôi đã viết. Tôi chơi lại cách đã dùng, trong

Kết

Thúc một Chuyện Tình, khi sử dụng ngôi thứ nhất, và cách chuyển

thời

[time-shift], để bảo đảm chất phóng sự. Cuộc họp báo ở Hà Nội không

phải là thí

dụ độc nhất của cái gọi là phóng sự trực tiếp. Tôi ở trong 1 chiến đấu

cơ (tay

phi công đếch thèm để ý đến lệnh của Tướng de Lattre, khi cho tôi tháp

tùng),

khi nó tấn công những điểm có Vẹm, ở trong toán tuần tra của lực lượng

Lê

Dương, bên ngoài Phát Diệm. Tôi vẫn còn giữ nguyên hình ảnh, 1 đứa bé

chết, bên

cạnh bà mẹ, dưới 1 con mương. Những vết đạn cực nét làm cho cái chết

của hai mẹ

con nhức nhối hơn nhiều, so với cuộc tàn sát làm nghẹt những con kinh

bên ngoài

nhà thờ Phát Diệm.

Tôi trở lại Đông Dương lần thứ tư và là lần cuối cùng vào năm 1955, sau cú thất trận của Tẩy ở Bắc Việt, và với tí khó khăn, tôi tới được Hà Nội, một thành phố buồn, bị tụi Tẩy bỏ rơi, tôi ngồi chơi chai bia cuối cùng [may quá, cũng bị tụi Tẩy] bỏ lại, trong 1 quán cà phê, nơi tôi thường tới với me-xừ Dupont. Tôi cảm thấy rất bịnh, mệt mỏi, tinh thần sa sút. Tôi có cảm tình với tụi thắng trận nhưng cũng có cảm tình với tụi Tẩy [làm sao không!] Những cuốn sách của những tác giả cổ điển Tẩy, thì vưỡn thấy được bày ở trong 1 tiệm sách nhỏ, chuyên bán sách cũ, nơi tôi và ông bạn nói trên cùng lục lọi, mấy năm về trước, nhưng 100 năm văn hóa thằng Tây mũi lõ thì đã theo tín hữu Ky Tô, nhà quê, Bắc Kít, bỏ chạy vô Miền Nam. Khách sạn Metropole, nơi tôi thường ở, thì nằm trong tay Phái Đoàn Quốc Tế [lo vụ Đình Chiến. NQT]. Mấy anh VC đứng gác bên ngoài tòa nhà, nơi Tướng De Lattre đã từng huênh hoang hứa nhảm, ‘tớ để bà xã ở lại, như là 1 bằng chứng nước Tẩy sẽ không bao giờ, không bao giờ….’

Tôi trở lại Đông Dương lần thứ tư và là lần cuối cùng vào năm 1955, sau cú thất trận của Tẩy ở Bắc Việt, và với tí khó khăn, tôi tới được Hà Nội, một thành phố buồn, bị tụi Tẩy bỏ rơi, tôi ngồi chơi chai bia cuối cùng [may quá, cũng bị tụi Tẩy] bỏ lại, trong 1 quán cà phê, nơi tôi thường tới với me-xừ Dupont. Tôi cảm thấy rất bịnh, mệt mỏi, tinh thần sa sút. Tôi có cảm tình với tụi thắng trận nhưng cũng có cảm tình với tụi Tẩy [làm sao không!] Những cuốn sách của những tác giả cổ điển Tẩy, thì vưỡn thấy được bày ở trong 1 tiệm sách nhỏ, chuyên bán sách cũ, nơi tôi và ông bạn nói trên cùng lục lọi, mấy năm về trước, nhưng 100 năm văn hóa thằng Tây mũi lõ thì đã theo tín hữu Ky Tô, nhà quê, Bắc Kít, bỏ chạy vô Miền Nam. Khách sạn Metropole, nơi tôi thường ở, thì nằm trong tay Phái Đoàn Quốc Tế [lo vụ Đình Chiến. NQT]. Mấy anh VC đứng gác bên ngoài tòa nhà, nơi Tướng De Lattre đã từng huênh hoang hứa nhảm, ‘tớ để bà xã ở lại, như là 1 bằng chứng nước Tẩy sẽ không bao giờ, không bao giờ….’

Ngày lại qua ngày, trong khi

tôi cố tìm cách gặp Bác Hát….

Graham

Greene: Ways of Escape

GCC đang hăm

he/hăm hở dịch tiếp đoạn, Greene làm “chantage” - Day after day passed

while I tried to bully my way into the presence of Ho Chi Minh, I

don't

know why my blackmail succeeded, but I was summoned suddenly to take

tea with

Ho Chi Minh meetin -, để Bác hoảng, phải cho gặp mặt.

*

*

Một số tiết lộ về cuộc chiến từ tài liệu CIA

Greene viết Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng, là cũng từ nguồn này, qua lần gặp gỡ một anh Xịa, khi đi thăm Le Roy, trên đường trở về Sài Gòn. (1)

(1)

Giấc mơ lớn của Mẽo, từ đó, cái mầm của Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng bật ra, khi Greene, trên đường trở về Sài Gòn, sau khi qua một đêm với tướng Leroy, Hùm Xám Bến Tre, như ông viết, trong Tam thập lục kế tẩu vi thượng sách, Ways of Escape.

"Cách đây chưa đầy một năm, [Geeene viết năm 1952], tôi đã từng tháp tùng Le Roy, tham quan vương quốc sông rạch, trên chiến thuyền của ông ta. Lần này, thay vì chiến thuyền, thì là du thuyền, thay vì dàn súng máy ở hai bên mạn thuyền, thì là chiếc máy chạy dĩa nhạc, và những vũ nữ.

Bản nhạc đang chơi, là từ phim Người Thứ Ba, như để vinh danh tôi.

Tôi dùng chung phòng ngủ với một tay Mẽo, tùy viên kinh tế, chắc là CIA, [an American attached to an economic aid mission - the members were assumed by the French, probably correctly, to belong to the CIA]. Không giống Pyle, thông minh hơn, và ít ngu hơn [of less innocence]. Anh ta bốc phét, suốt trên đường từ Bến Tre về Sài Gòn, về sự cần thiết phải tìm cho ra một lực lượng thứ ba ở Việt Nam.

Cho tới lúc đó, tôi chưa bao giờ cận kề với giấc mộng lớn của Mẽo, về những áp phe ma quỉ, tại Đông phương, như là nó đã từng, tại Phi Châu.

Trong Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng, Pyle nhắc tới câu của tay ký giả York Harding – cái mà phía Đông cần, là một Lực Lượng Thứ Ba – anh ta xem có vẻ ngây thơ, nhưng thực sự đây chính là chính sách của Mẽo.

Người Mẽo tìm kiếm một nhà lãnh đạo Việt Nam không tham nhũng, hoàn toàn quốc gia, an incorruptible, purely nationalist Vietnamese leader, người có thể kết hợp, unite, nhân dân Việt Nam, và tạo thành một thế đứng, một giải pháp, đối với Việt Minh CS."

Greene rất chắc chắn, về nguồn của Người Mỹ trầm lặng:

"Như vậy, đề tài NMTL tới với tôi, trong cuộc nói chuyện trên, về 'lực lượng thứ ba', trên đường vượt đồng bằng sông Cửu Long, và từ đó, những nhân vật theo sau, tất cả, [trừ một, Granger], là từ tiềm thức bật ra."

Ways of escape

NKTV: 30.4.2912_1

Trong cuốn

tiểu sử của Greene, thì “Lực Lượng Thứ Ba”, anh Xịa ngây thơ gặp, là

Trình Minh

Thế. Greene không ưa TMT, và không tin ông làm được trò gì. Nhưng chỉ

đến khi

TMT bị Diệm thịt, thì ông mới thay đổi thái độ, như trong cái thư mở ra

"Người Mỹ

Trầm Lặng" cho thấy.

Theo GCC, cuốn NMTL được

phát sinh, là từ cái tên Phượng, đúng như

trong tiềm

thức của Greene mách bảo ông.

Cả cuốn truyện là từ đó mà ra. Và nó còn tiên tri ra được cuộc xuất cảng người phụ nữ Mít cả trước và sau cuộc chiến, đúng như lời anh ký giả Hồng Mao ghiền khuyên Pyle, mi hãy quên “lực lượng thứ ba” và đem Phượng về Mẽo, quên cha luôn cái xứ sở khốn kiếp Mít này đi!

Cả cuốn truyện là từ đó mà ra. Và nó còn tiên tri ra được cuộc xuất cảng người phụ nữ Mít cả trước và sau cuộc chiến, đúng như lời anh ký giả Hồng Mao ghiền khuyên Pyle, mi hãy quên “lực lượng thứ ba” và đem Phượng về Mẽo, quên cha luôn cái xứ sở khốn kiếp Mít này đi!

The Life of

Graham Greene

Volume 2: 1939-1955

Norman Sherry

Volume 2: 1939-1955

Norman Sherry

Note: Một

trong những em Phượng, đi đúng những ngày 30 Tháng Tư, 1975, và là 1

trong những

nhà văn nữ hàng đầu của Miền Nam trước 1975, khi Gấu tới trại tị nạn,

gửi thư cầu

cứu, đã than giùm, anh đi trễ quá, Miền Biển Động hết động rồi.

Sao không ở luôn

với số phận xứ Mít [ở với VC?]

"Phuong,"

I said – which means Phoenix, but nothing nowadays is fabulous and

nothing

rises from its ashes. "Phượng", tôi nói, "Phượng có nghĩa là Phượng

hoàng, nhưng những ngày này chẳng có chi là huyền hoặc, và chẳng có gì

tái sinh

từ mớ tro than của loài chim đó":

Quả có sự

tái sinh từ mớ than của loài chim đó! Cuộc xuất cảng Phượng sau 1975,

là cả 1

cái nguồn nuôi nước Mít, theo nghĩa thê thảm nhất, hoặc, cao cả nhất

[Hãy nghĩ

đến những gia đình Miền Nam phải cho con gái đi làm dâu Đại Hàn,

thí dụ,

để sống sót VC]

Võ tướng quân về Trời

Greene đi tuần tra cùng lính Pháp tại Phát Diệm

So the

subject of The Quiet American came to

me, during that talk of a 'third force' on the road through the delta,

and my

characters quickly followed, all but one of them from the unconscious.

The

exception was Granger, the American newspaper correspondent. The press

conference in Hanoi where he figures was recorded almost word for word

in my

journal at the time. Perhaps there is more direct reportage in The Quiet American than in any other

novel I have written. I had determined to employ again the experience I

had

gained with The End of the Affair in

the use of the first person and the time-shift, and my choice of a

journalist

as the 'I' seemed to me to justify the use of reportage. The press

conference

is not the only example of direct reporting. I was in the dive-bomber

(the

pilot had broken an order of General de Lattre by taking me) which

attacked the

Viet Minh post and I was on the patrol of the Foreign Legion paras

outside Phat

Diem. I still retain the sharp image of the dead child couched in the

ditch

beside his dead mother. The very neatness of their bullet wounds made

their death

more disturbing than the indiscriminate massacre in the canals around.

I went back to Indo-China for the fourth and last time in 1955 after the defeat of the French in the north, and with some difficulty I reached Hanoi - a sad city, abandoned by the French, where I drank the last bottle of beer left in the cafe which I used to frequent with Monsieur Dupont. I was feeling very ill and tired and depressed. I sympathized with the victors, but I sympathized with the French too. The French classics were yet on view in a small secondhand bookshop which Monsieur Dupont had rifled a few years back, but a hundred years of French civilization had fled with the Catholic peasants to the south. The Metropole Hotel where I used to stay was in the hands of the International Commission. Viet Minh sentries stood outside the building where de Lattre had made his promise, 'I leave you my wife as a symbol that France will never, never ... ' Day after day passed while I tried to bully my way into the presence of Ho Chi Minh. It was the period of the crachin and my spirits sank with the thin day-long drizzle of warm rain. I told my contacts I could wait no longer - tomorrow I - would return to what was left of French territory in the north.

I don't know why my blackmail succeeded, but I was summoned suddenly to take tea with Ho Chi Minh, and now I felt too ill for the meeting. There was only one thing to be done. I went back to an old Chinese chemist's shop in the rue des Voiles which I had visited the year before. The owner, it was said, was 'the Happiest Man in the World’. There I was able to smoke a few pipes of opium while the mah-jong pieces rattled like gravel on a beach. I had a passionate desire for the impossible - a bottle of Eno's. A messenger was dispatched and before the pipes were finished I received the impossible. I had drunk the last bottle of beer in Hanoi. Was this the last bottle of Eno's? Anyway the Eno's and the pipes took away the sickness and the inertia and gave me the energy to meet Ho Chi Minh at tea.

Of those four winters which I passed in Indo-China opium has left the happiest memory, and as it played an important part in the life of Fowler, my character in The Quiet American, I add a few memories from my journal concerning it, for I am reluctant to leave Indo-China for ever with only a novel to remember it by.

I went back to Indo-China for the fourth and last time in 1955 after the defeat of the French in the north, and with some difficulty I reached Hanoi - a sad city, abandoned by the French, where I drank the last bottle of beer left in the cafe which I used to frequent with Monsieur Dupont. I was feeling very ill and tired and depressed. I sympathized with the victors, but I sympathized with the French too. The French classics were yet on view in a small secondhand bookshop which Monsieur Dupont had rifled a few years back, but a hundred years of French civilization had fled with the Catholic peasants to the south. The Metropole Hotel where I used to stay was in the hands of the International Commission. Viet Minh sentries stood outside the building where de Lattre had made his promise, 'I leave you my wife as a symbol that France will never, never ... ' Day after day passed while I tried to bully my way into the presence of Ho Chi Minh. It was the period of the crachin and my spirits sank with the thin day-long drizzle of warm rain. I told my contacts I could wait no longer - tomorrow I - would return to what was left of French territory in the north.

I don't know why my blackmail succeeded, but I was summoned suddenly to take tea with Ho Chi Minh, and now I felt too ill for the meeting. There was only one thing to be done. I went back to an old Chinese chemist's shop in the rue des Voiles which I had visited the year before. The owner, it was said, was 'the Happiest Man in the World’. There I was able to smoke a few pipes of opium while the mah-jong pieces rattled like gravel on a beach. I had a passionate desire for the impossible - a bottle of Eno's. A messenger was dispatched and before the pipes were finished I received the impossible. I had drunk the last bottle of beer in Hanoi. Was this the last bottle of Eno's? Anyway the Eno's and the pipes took away the sickness and the inertia and gave me the energy to meet Ho Chi Minh at tea.

Of those four winters which I passed in Indo-China opium has left the happiest memory, and as it played an important part in the life of Fowler, my character in The Quiet American, I add a few memories from my journal concerning it, for I am reluctant to leave Indo-China for ever with only a novel to remember it by.

Graham Greene: Ways of Escape

Như vậy là đề

tài Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng đến với tôi,

trong cuộc “chat”, về “lực lượng thứ ba” trên con đường đồng bằng [Nam

Bộ] và

những nhân vật của tôi bèn lẵng nhẵng đi theo, tất cả, trừ 1 trong số

họ, là từ

tiềm thức. Ngoại lệ, là Granger, tay ký

giả Mẽo. Cuộc họp báo ở Hà Nội, có anh ta, được ghi lại, gần như từng

lời, từ

nhật ký của tôi, vào thời kỳ đó.

Có lẽ cái chất phóng sự của Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng nặng “đô” hơn, so với bất cứ cuốn tiểu thuyết nào mà tôi đã viết. Tôi chơi lại cách đã dùng, trong Kết Thúc một Chuyện Tình, khi sử dụng ngôi thứ nhất, và cách chuyển thời [time-shift], để bảo đảm chất phóng sự. Cuộc họp báo ở Hà Nội không phải là thí dụ độc nhất của cái gọi là phóng sự trực tiếp. Tôi ở trong 1 chiến đấu cơ (tay phi công đếch thèm để ý đến lệnh của Tướng de Lattre, khi cho tôi tháp tùng), khi nó tấn công những điểm có Vẹm, ở trong toán tuần tra của lực lượng Lê Dương, bên ngoài Phát Diệm. Tôi vẫn còn giữ nguyên hình ảnh, 1 đứa bé chết, bên cạnh bà mẹ, dưới 1 con mương. Những vết đạn cực nét làm cho cái chết của hai mẹ con nhức nhối hơn nhiều, so với cuộc tàn sát làm nghẹt những con kinh bên ngoài nhà thờ Phát Diệm.

Tôi trở lại Đông Dương lần thứ tư và là lần cuối cùng vào năm 1955, sau cú thất trận của Tẩy ở Bắc Việt, và với tí khó khăn, tôi tới được Hà Nội...

Ways of EscapeCó lẽ cái chất phóng sự của Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng nặng “đô” hơn, so với bất cứ cuốn tiểu thuyết nào mà tôi đã viết. Tôi chơi lại cách đã dùng, trong Kết Thúc một Chuyện Tình, khi sử dụng ngôi thứ nhất, và cách chuyển thời [time-shift], để bảo đảm chất phóng sự. Cuộc họp báo ở Hà Nội không phải là thí dụ độc nhất của cái gọi là phóng sự trực tiếp. Tôi ở trong 1 chiến đấu cơ (tay phi công đếch thèm để ý đến lệnh của Tướng de Lattre, khi cho tôi tháp tùng), khi nó tấn công những điểm có Vẹm, ở trong toán tuần tra của lực lượng Lê Dương, bên ngoài Phát Diệm. Tôi vẫn còn giữ nguyên hình ảnh, 1 đứa bé chết, bên cạnh bà mẹ, dưới 1 con mương. Những vết đạn cực nét làm cho cái chết của hai mẹ con nhức nhối hơn nhiều, so với cuộc tàn sát làm nghẹt những con kinh bên ngoài nhà thờ Phát Diệm.

Tôi trở lại Đông Dương lần thứ tư và là lần cuối cùng vào năm 1955, sau cú thất trận của Tẩy ở Bắc Việt, và với tí khó khăn, tôi tới được Hà Nội...

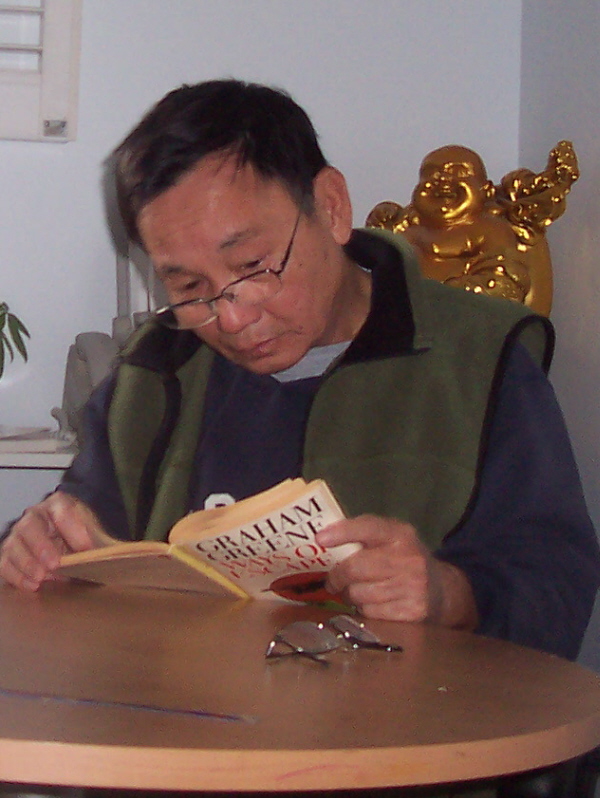

Cuốn này mua

từ hồi nào, bi giờ mới thấy, sau khi lục lọi, cố tìm cuốn Phân tâm học về

Lửa của Bachelard, để đọc lại. Coi lửa của Bachelard có tí nhân ái

nào

không so với lửa của QD, ông anh ruột của Thầy Phúc.

Hà, hà!

Cuốn này, nằm trong 1 chùm

mà 1 em nữ phê bình gia phán, trung tâm điểm

của khá nhiều cái viết của Greene [Brighton

Rock, The Power and the

Glory, The

Heart of the matter] là tự tử, mà theo như Ky Tô giáo, đây là

tội nặng

nhất. Và

nhà văn bèn phịa ra 1 câu để bào chữa cho quan điểm của ông: Tui là tác

giả, và

tác giả này thì là một tín hữu Kytô, “I am an author who is a Catholic”

Ways of escape: Tam

thập lục kế, tẩu vi

thượng sách!

Hồi ký của Greene. Những đoạn viết về Việt Nam thật tuyệt.

Hồi ký của Greene. Những đoạn viết về Việt Nam thật tuyệt.

Trở lại

Anh, Greene nhớ Việt Nam

quá và đã

mang theo cùng với ông một cái tẩu hít tô phe, như là một kỷ niệm tình

cảm: cái

tẩu mà ông đã hít lần chót, tại một tiệm hít ngoài đường Catinat. Tay chủ, người Tầu hợp với ông, và ông đã đi vài

đường

dậy tay này vài câu tiếng Anh. Tới ngày rời Việt Nam,

tay chủ tiệm hít bèn giúi vào

tay Greene cái tẩu. Cây gậy thiêng nằm trên một cái dĩa tại căn phòng

của

Greene, ở Albany,

bị sứt mẻ tí tí, do di chuyển, đúng là một thần vật cổ, của những ngày

hạnh

phúc.

Lần thăm Việt Nam cuối, chàng [Greene] hít nhiều hơn lệ thường: thường, nghĩa là ba hoặc bốn bi, nhưng chỉ riêng trong lần cuối này, ở Sài Gòn, trong khi chờ đợi một tờ visa khác, tiếu lâm thay, của Vi Xi, chàng "thuốc" chàng đến bất tri bất giác, he smoked himself inerte.

Trong những lần trước, thường xuyên là với những viên chức Tây, chàng hít không quá hai lần trong một tuần. Lần này, một tuần hít ba lần, mỗi lần trên mười bi. Ngay cả hít nhiều như thế cũng chẳng đủ biến chàng thành ghiền. Ghiền, là phải hít trên trăm bi một ngày.

Norman Sherry: Tiểu sử Greene

Trong Ba Mươi Sáu Chước, Tẩu Vi Thượng Sách, Ways of escape, một dạng hồi nhớ văn học, Greene cho biết, đúng là một cơ may, chuyện ông chết mê chết mệt xứ Đông Dương. Lần thứ nhất viếng thăm, ông chẳng hề nghĩ, mình sẽ đẻ ra được một cuốn tiểu thuyết thật bảnh, nhờ nó. Một người bạn cũ của ông, từ hồi chiến tranh, lúc đó là Lãnh sự tại Hà Nội, nơi một cuộc chiến tranh khác đang tiến diễn và hầu như hoàn toàn bị bỏ quên bởi báo chí Anh. Do đó, sau Malaya, ông bèn nháng qua Việt Nam thăm bạn, chẳng hề nghĩ, vài năm sau, sẽ trải qua tất cả những mùa đông của ông ở đây.

"Tôi nhận thấy, Malaya 'đần' như một người đàn bà đẹp đôi khi 'độn'. Người ở đó thường nói, 'Bạn phải thăm xứ xở này vào thời bình', và tôi thật tình muốn vặc lại, 'Nhưng tớ chỉ quan tâm tới cái xứ sở đần độn này, khi có máu'. Không có máu, nó trơ ra với vài câu lạc bộ Anh, với một dúm xì căng đan nho nhỏ, nằm tênh hênh chờ một tay Maugham nào đó mần báo cáo về chúng."

"Nhưng Đông Dương, khác hẳn. Ở đó, tôi nuốt trọn bùa yêu, ngải lú, tôi cụng ly rượu tình với mấy đám sĩ quan Lực Lượng Lê Dương, mắt tay nào cũng sáng lên, khi vừa nghe nhắc đến hai tiếng Sài Gòn, hay Hà Nội."

Và bùa yêu ép phê liền tù tì, tôi muốn nói, giáng cú sét đánh đầu tiên của nó, qua những cô gái mảnh khảnh, thanh lịch, trong những chiếc quần lụa trắng, qua cái dáng chiều mầu thiếc xà xuống cánh đồng lúa trải dài ra mãi, đây đó là mấy chú trâu nước nặng nề trong cái dáng đi lảo đảo hai bên móng vốn có tự thời nguyên thuỷ của loài vật này, hay là qua mấy tiệm bán nước thơm của người Tây ở đường Catinat, hay trong những sòng bài bạc của người Tầu ở Chợ Lớn, nhưng trên hết, là qua cái cảm giác bi bi hài hài, trớ trêu làm sao, và cũng rất ư là phấn chấn hồ hởi mà một dấu báo của hiểm nguy mang đến cho du khách với cái vé khứ hồi thủ sẵn ở trong túi: những tiệm ăn bao quanh bằng những hàng dây kẽm gai nhằm chống lại lựu đạn, những vọng gác cao lênh khênh dọc theo những con lộ nơi đồng bằng Nam Bộ với những lời cảnh báo thật là kỳ kỳ [bằng tiếng Tây, lẽ dĩ nhiên]: "Nếu bạn bị tấn công, và bị bắt giữ trên đường đi, hãy báo liền lập tức cho viên sếp đồn quan trọng đầu tiên".

Dịp đó, tôi ở hai tuần, và tranh thủ tối đa, tới giây phút cuối cùng, cái giây phút không thể tha thứ , "the unforgiving minute". Hà Nội cách Sài Gòn bằng London xa Rome, nhưng ngoài chuyện ăn ngủ... ở cả hai thành phố, tôi còn ban cho mình những chuyến tham quan nơi đồng bằng Nam Bộ, tới những giáo phái lạ lùng như Cao Đài mà những ông thánh của nó bao gồm Victor Hugo, Christ, Phật, và Tôn Dật Tiên.

Lần thăm Việt Nam cuối, chàng [Greene] hít nhiều hơn lệ thường: thường, nghĩa là ba hoặc bốn bi, nhưng chỉ riêng trong lần cuối này, ở Sài Gòn, trong khi chờ đợi một tờ visa khác, tiếu lâm thay, của Vi Xi, chàng "thuốc" chàng đến bất tri bất giác, he smoked himself inerte.

Trong những lần trước, thường xuyên là với những viên chức Tây, chàng hít không quá hai lần trong một tuần. Lần này, một tuần hít ba lần, mỗi lần trên mười bi. Ngay cả hít nhiều như thế cũng chẳng đủ biến chàng thành ghiền. Ghiền, là phải hít trên trăm bi một ngày.

Norman Sherry: Tiểu sử Greene

Trong Ba Mươi Sáu Chước, Tẩu Vi Thượng Sách, Ways of escape, một dạng hồi nhớ văn học, Greene cho biết, đúng là một cơ may, chuyện ông chết mê chết mệt xứ Đông Dương. Lần thứ nhất viếng thăm, ông chẳng hề nghĩ, mình sẽ đẻ ra được một cuốn tiểu thuyết thật bảnh, nhờ nó. Một người bạn cũ của ông, từ hồi chiến tranh, lúc đó là Lãnh sự tại Hà Nội, nơi một cuộc chiến tranh khác đang tiến diễn và hầu như hoàn toàn bị bỏ quên bởi báo chí Anh. Do đó, sau Malaya, ông bèn nháng qua Việt Nam thăm bạn, chẳng hề nghĩ, vài năm sau, sẽ trải qua tất cả những mùa đông của ông ở đây.

"Tôi nhận thấy, Malaya 'đần' như một người đàn bà đẹp đôi khi 'độn'. Người ở đó thường nói, 'Bạn phải thăm xứ xở này vào thời bình', và tôi thật tình muốn vặc lại, 'Nhưng tớ chỉ quan tâm tới cái xứ sở đần độn này, khi có máu'. Không có máu, nó trơ ra với vài câu lạc bộ Anh, với một dúm xì căng đan nho nhỏ, nằm tênh hênh chờ một tay Maugham nào đó mần báo cáo về chúng."

"Nhưng Đông Dương, khác hẳn. Ở đó, tôi nuốt trọn bùa yêu, ngải lú, tôi cụng ly rượu tình với mấy đám sĩ quan Lực Lượng Lê Dương, mắt tay nào cũng sáng lên, khi vừa nghe nhắc đến hai tiếng Sài Gòn, hay Hà Nội."

Và bùa yêu ép phê liền tù tì, tôi muốn nói, giáng cú sét đánh đầu tiên của nó, qua những cô gái mảnh khảnh, thanh lịch, trong những chiếc quần lụa trắng, qua cái dáng chiều mầu thiếc xà xuống cánh đồng lúa trải dài ra mãi, đây đó là mấy chú trâu nước nặng nề trong cái dáng đi lảo đảo hai bên móng vốn có tự thời nguyên thuỷ của loài vật này, hay là qua mấy tiệm bán nước thơm của người Tây ở đường Catinat, hay trong những sòng bài bạc của người Tầu ở Chợ Lớn, nhưng trên hết, là qua cái cảm giác bi bi hài hài, trớ trêu làm sao, và cũng rất ư là phấn chấn hồ hởi mà một dấu báo của hiểm nguy mang đến cho du khách với cái vé khứ hồi thủ sẵn ở trong túi: những tiệm ăn bao quanh bằng những hàng dây kẽm gai nhằm chống lại lựu đạn, những vọng gác cao lênh khênh dọc theo những con lộ nơi đồng bằng Nam Bộ với những lời cảnh báo thật là kỳ kỳ [bằng tiếng Tây, lẽ dĩ nhiên]: "Nếu bạn bị tấn công, và bị bắt giữ trên đường đi, hãy báo liền lập tức cho viên sếp đồn quan trọng đầu tiên".

Dịp đó, tôi ở hai tuần, và tranh thủ tối đa, tới giây phút cuối cùng, cái giây phút không thể tha thứ , "the unforgiving minute". Hà Nội cách Sài Gòn bằng London xa Rome, nhưng ngoài chuyện ăn ngủ... ở cả hai thành phố, tôi còn ban cho mình những chuyến tham quan nơi đồng bằng Nam Bộ, tới những giáo phái lạ lùng như Cao Đài mà những ông thánh của nó bao gồm Victor Hugo, Christ, Phật, và Tôn Dật Tiên.

Ways of

escape

Liệu

giấc mơ về một cuộc

cách mạng, thỏa mãn giấc mơ như lòng chúng ta

thèm

khát tương lai, của TTT, có gì liên can tới ‘lực lượng thứ ba’, vốn là

một giấc

mơ lớn, của Mẽo, nằm trong hành trang của Pyle, [Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng

],

khi tới Việt Nam.Giấc mơ lớn của Mẽo, từ đó, cái mầm của Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng bật ra, khi Greene, trên đường trở về Sài Gòn, sau khi qua một đêm với tướng Leroy, Hùm Xám Bến Tre, như ông viết, trong Tam thập lục kế tẩu vi thượng sách, Ways of Escape.

"Cách đây chưa đầy một năm, [Geeene viết năm 1952], tôi đã từng tháp tùng Le Roy, tham quan vương quốc sông rạch, trên chiến thuyền của ông ta. Lần này, thay vì chiến thuyền, thì là du thuyền, thay vì dàn súng máy ở hai bên mạn thuyền, thì là chiếc máy chạy dĩa nhạc, và những vũ nữ.

Bản nhạc đang chơi, là từ phim Người Thứ Ba, như để vinh danh tôi.

Tôi dùng chung phòng ngủ với một tay Mẽo, tùy viên kinh tế, chắc là CIA, [an American attached to an economic aid mission - the members were assumed by the French, probably correctly, to belong to the CIA]. Không giống Pyle, thông minh hơn, và ít ngu hơn [of less innocence]. Anh ta bốc phét, suốt trên đường từ Bến Tre về Sài Gòn, về sự cần thiết phải tìm cho ra một lực lượng thứ ba ở Việt Nam. Cho tới lúc đó, tôi chưa giờ cận kề với giấc mộng lớn của Mẽo, về những áp phe ma quỉ, tại Đông phương, như là nó đã từng, tại Phi Châu.

Trong Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng, Pyle nhắc tới câu của tay ký giả York Harding – cái mà phía Đông cần, là một Lực Lượng Thứ Ba – anh ta xem có vẻ ngây thơ, nhưng thực sự đây chính là chính sách của Mẽo. Người Mẽo tìm kiếm một nhà lãnh đạo Việt Nam không tham nhũng, hoàn toàn quốc gia, an incorruptible, purely nationalist Vietnamese leader, người có thể kết hợp, unite, nhân dân Việt Nam, và tạo thành một thế đứng, một giải pháp, đối với Việt Minh CS.

Greene rất chắc chắn, về nguồn của Người Mỹ trầm lặng:

"Như vậy, đề tài NMTL tới với tôi, trong cuộc nói chuyện trên, về 'lực lượng thứ ba', trên đường vượt đồng bằng sông Cửu Long, và từ đó, những nhân vật theo sau, tất cả, [trừ một, Granger], là từ tiềm thức bật ra."

Ways of Escape.

Granger, một ký giả Mẽo, tên thực ngoài đời, Larry Allen, đã từng được Pulitzer khi tường thuật Đệ Nhị Chiến, chín năm trước đó. Greene gặp anh ta năm 1951. Khi đó 43 tuổi, hào quang đã ở đằng sau, nhậu như hũ chìm. Khi, một tay nâng bi anh ta về bài viết, [Tên nó là gì nhỉ, Đường về Địa ngục, đáng Pulitzer quá đi chứ... ], Allen vặc lại: "Bộ anh nghĩ, tôi có ở đó hả? Stephen Crane đã từng miêu tả một cuộc chiến mà ông không có mặt, tại sao tôi không thể? Vả chăng, chỉ là một cuộc chiến thuộc địa nhơ bẩn. Cho ly nữa đi. Rồi tụi mình đi kiếm gái."

Trong Tẩu Vi Thượng Sách. Greene có kể về mối tình của ông đối với Miền Nam Việt Nam, và từ đó, đưa đến chuyện ông viết Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng…

Tin Văn post lại ở đây, như là một dữ kiện, cho thấy, Mẽo thực sự không có ý ‘giầy xéo’ Miền Nam.

Và cái cú đầu độc tù Phú Lợi, hẳn là ‘diệu kế’ của đám VC nằm vùng.

Cái chuyện MB phải thống nhất đất nước, là đúng theo qui luật lịch sử xứ Mít, nhưng, do dùng phương pháp bá đạo mà hậu quả khủng khiếp 'nhãn tiền’ như ngày nay!

Ui chao, lại nhớ cái đoạn trong Tam Quốc, khi Lưu Bị thỉnh thị quân sư Khổng Minh, làm cách nào lấy được xứ... Nam Kỳ, Khổng Minh bèn phán, có ba cách, vương đạo, trung đạo, và bá đạo [Gấu nhớ đại khái].

Sau khi nghe trình bầy, Lê Duẩn than, vương đạo khó quá, bụng mình đầy cứt, làm sao nói chuyện vương đạo, thôi, bá đạo đi!

Cú Phú Lợi đúng là như thế! Và cái giá của mấy anh tù VC Phú Lợi, giả như có, là cả cuộc chiến khốn kiếp!

*

Ways of escape: Tam thập lục kế, tẩu vi thượng sách!

Hồi ký của Greene. Những đoạn viết về Việt Nam thật tuyệt.

Trở lại Anh, Greene nhớ Việt Nam quá và đã mang theo cùng với ông một cái tẩu hít tô phe, như là một kỷ niệm tình cảm: cái tẩu mà ông đã hít lần chót, tại một tiệm hít ngoài đường Catinat. Tay chủ, người Tầu hợp với ông, và ông đã đi vài đường dậy tay này vài câu tiếng Anh. Tới ngày rời Việt Nam, tay chủ tiệm hít bèn giúi vào tay Greene cái tẩu. Cây gậy thiêng nằm trên một cái dĩa tại căn phòng của Greene, ở Albany, bị sứt mẻ tí tí, do di chuyển, đúng là một thần vật cổ, của những ngày hạnh phúc.

Lần thăm Việt Nam cuối, chàng [Greene] hít nhiều hơn lệ thường: thường, nghĩa là ba hoặc bốn bi, nhưng chỉ riêng trong lần cuối này, ở Sài Gòn, trong khi chờ đợi một tờ visa khác, tiếu lâm thay, của Vi Xi, chàng "thuốc" chàng đến bất tri bất giác, he smoked himself inerte.

Trong những lần trước, thường xuyên là với những viên chức Tây, chàng hít không quá hai lần trong một tuần. Lần này, một tuần hít ba lần, mỗi lần trên mười bi. Ngay cả hít nhiều như thế cũng chẳng đủ biến chàng thành ghiền. Ghiền, là phải hít trên trăm bi một ngày.

Norman Sherry: Tiểu sử Greene

*

Trong Ba Mươi Sáu Chước, Tẩu Vi Thượng Sách, Ways of escape, một dạng hồi nhớ văn học, Greene cho biết, đúng là một cơ may, chuyện ông chết mê chết mệt xứ Đông Dương. Lần thứ nhất viếng thăm, ông chẳng hề nghĩ, mình sẽ đẻ ra được một cuốn tiểu thuyết thật bảnh, nhờ nó. Một người bạn cũ của ông, từ hồi chiến tranh, lúc đó là Lãnh sự tại Hà Nội, nơi một cuộc chiến tranh khác đang tiến diễn và hầu như hoàn toàn bị bỏ quên bởi báo chí Anh. Do đó, sau Malaya, ông bèn nháng qua Việt Nam thăm bạn, chẳng hề nghĩ, vài năm sau, sẽ trải qua tất cả những mùa đông của ông ở đây.

"Tôi nhận thấy, Malaya 'đần' như một người đàn bà đẹp đôi khi 'độn'. Người ở đó thường nói, 'Bạn phải thăm xứ xở này vào thời bình', và tôi thật tình muốn vặc lại, 'Nhưng tớ chỉ quan tâm tới cái xứ sở đần độn này, khi có máu'. Không có máu, nó trơ ra với vài câu lạc bộ Anh, với một dúm xì căng đan nho nhỏ, nằm tênh hênh chờ một tay Maugham nào đó mần báo cáo về chúng."

"Nhưng Đông Dương, khác hẳn. Ở đó, tôi nuốt trọn bùa yêu, ngải lú, tôi cụng ly rượu tình với mấy đám sĩ quan Lực Lượng Lê Dương, mắt tay nào cũng sáng lên, khi vừa nghe nhắc đến hai tiếng Sài Gòn, hay Hà Nội."

Và bùa yêu ép phê liền tù tì, tôi muốn nói, giáng cú sét đánh đầu tiên của nó, qua những cô gái mảnh khảnh, thanh lịch, trong những chiếc quần lụa trắng, qua cái dáng chiều mầu thiếc xà xuống cánh đồng lúa trải dài ra mãi, đây đó là mấy chú trâu nước nặng nề trong cái dáng đi lảo đảo hai bên mông vốn có tự thời nguyên thuỷ của loài vật này, hay là qua mấy tiệm bán nước thơm của người Tây ở đường Catinat, hay trong những sòng bài của người Tầu ở Chợ Lớn, nhưng trên hết, là qua cái cảm giác bi bi hài hài, trớ trêu làm sao, và cũng rất ư là phấn chấn hồ hởi mà một dấu báo của hiểm nguy mang đến cho du khách với cái vé khứ hồi thủ sẵn ở trong túi: những tiệm ăn bao quanh bằng những hàng dây kẽm gai nhằm chống lại lựu đạn, những vọng gác cao lênh khênh dọc theo những con lộ nơi đồng bằng Nam Bộ với những lời cảnh báo thật là kỳ kỳ [bằng tiếng Tây, lẽ dĩ nhiên]: "Nếu bạn bị tấn công, và bị bắt giữ trên đường đi, hãy báo liền lập tức cho viên sếp đồn quan trọng đầu tiên".

Dịp đó, tôi ở hai tuần, và tranh thủ tối đa, tới giây phút cuối cùng, cái giây phút không thể tha thứ , "the unforgiving minute". Hà Nội cách Sài Gòn bằng London xa Rome, nhưng ngoài chuyện ăn ngủ... ở cả hai thành phố, tôi còn ban cho mình những chuyến tham quan nơi đồng bằng Nam Bộ, tới những giáo phái lạ lùng như Cao Đài mà những ông thánh của nó bao gồm Victor Hugo, Christ, Phật, và Tôn Dật Tiên.

Ways of escape

Liệu giấc mơ về một cuộc cách mạng, thỏa mãn giấc mơ như lòng chúng ta thèm khát tương lai, của TTT, có gì liên can tới ‘lực lượng thứ ba’, vốn là một giấc mơ lớn, của Mẽo, nằm trong hành trang của Pyle, [Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng ], khi tới Việt Nam.

Giấc mơ lớn của Mẽo, từ đó, cái mầm của Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng bật ra, khi Greene, trên đường trở về Sài Gòn, sau khi qua một đêm với tướng Leroy, Hùm Xám Bến Tre, như ông viết, trong Tam thập lục kế tẩu vi thượng sách, Ways of Escape.

"Cách đây chưa đầy một năm, [Geeene viết năm 1952], tôi đã từng tháp tùng Le Roy, tham quan vương quốc sông rạch, trên chiến thuyền của ông ta. Lần này, thay vì chiến thuyền, thì là du thuyền, thay vì dàn súng máy ở hai bên mạn thuyền, thì là chiếc máy chạy dĩa nhạc, và những vũ nữ.

Bản nhạc đang chơi, là từ phim Người Thứ Ba, như để vinh danh tôi.

Tôi dùng chung phòng ngủ với một tay Mẽo, tùy viên kinh tế, chắc là CIA, [an American attached to an economic aid mission - the members were assumed by the French, probably correctly, to belong to the CIA]. Không giống Pyle, thông minh hơn, và ít ngu hơn [of less innocence]. Anh ta bốc phét, suốt trên đường từ Bến Tre về Sài Gòn, về sự cần thiết phải tìm cho ra một lực lượng thứ ba ở Việt Nam. Cho tới lúc đó, tôi chưa giờ cận kề với giấc mộng lớn của Mẽo, về những áp phe ma quỉ, tại Đông phương, như là nó đã từng, tại Phi Châu.

Trong Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng, Pyle nhắc tới câu của tay ký giả York Harding – cái mà phía Đông cần, là một Lực Lượng Thứ Ba – anh ta xem có vẻ ngây thơ, nhưng thực sự đây chính là chính sách của Mẽo. Người Mẽo tìm kiếm một nhà lãnh đạo Việt Nam không tham nhũng, hoàn toàn quốc gia, an incorruptible, purely nationalist Vietnamese leader, người có thể kết hợp, unite, nhân dân Việt Nam, và tạo thành một thế đứng, một giải pháp, đối với Việt Minh CS.

Greene rất chắc chắn, về nguồn của Người Mỹ trầm lặng:

"Như vậy, đề tài NMTL tới với tôi, trong cuộc nói chuyện trên, về 'lực lượng thứ ba', trên đường vượt đồng bằng sông Cửu Long, và từ đó, những nhân vật theo sau, tất cả, [trừ một, Granger], là từ tiềm thức bật ra."

Ways of Escape.

Granger, một ký giả Mẽo, tên thực ngoài đời, Larry Allen, đã từng được Pulitzer khi tường thuật Đệ Nhị Chiến, chín năm trước đó. Greene gặp anh ta năm 1951. Khi đó 43 tuổi, hào quang đã ở đằng sau, nhậu như hũ chìm. Khi, một tay nâng bi anh ta về bài viết, [Tên nó là gì nhỉ, Đường về Địa ngục, đáng Pulitzer quá đi chứ... ], Allen vặc lại: "Bộ anh nghĩ, tôi có ở đó hả? Stephen Crane đã từng miêu tả một cuộc chiến mà ông không có mặt, tại sao tôi không thể? Vả chăng, chỉ là một cuộc chiến thuộc địa nhơ bẩn. Cho ly nữa đi. Rồi tụi mình đi kiếm gái."

*

I shared a room that night with an American attached to an economic aid mission - the members were assumed by the French, probably correctly, to belong to the CIA. My companion bore no resemblance at all to Pyle, the quiet American of my story - he was a man of greater intelligence and of less innocence, but he lectured me all the long drive back to Saigon on the necessity of finding a 'third force in Vietnam'. I had never before come so close to the great American dream which was to bedevil affairs in the East as it was to do in Algeria. The only leader discernible for the 'third force' was the self· styled General The. At the time of my first visit to the Caodaists he had been a colonel in the army of the Caodaist Pope - a force of twenty thousand men which theoretically fought on the French side. They had their own munitions factory in the Holy See at Tay Ninh; they supplemented what small arms they could squeeze out of the French with mortars made from the exhaust pipes of old cars. An ingenious people - it was difficult not to suspect their type of ingenuity in the bicycle bombs which went off in Saigon the following year. The time-bombs were concealed in plastic containers made in the shape of bicycle pumps and the bicycles were left in the parks outside the ministries and propped against walls ... A bicycle arouses no attention in Saigon. It is as much a bicycle city as Copenhagen.

Between my two visits General The (he had promoted himself) had deserted from the Caodaist army with a few hundred men and was now installed on the Holy Mountain, outside Tay Ninh. He had declared war on both the French and the Communists. When my novel was eventually noticed in the New Yorker the reviewer condemned me for accusing my 'best friends' (the Americans) of murder since I had attributed to them the responsibility for the great explosion - far worse than the trivial bicycle bombs - in the main square of Saigon when many people lost their lives. But what are the facts, of which the reviewer needless to say was ignorant? The Life photographer at the moment of the explosion was so well placed that he was able to take an astonishing and horrifying photograph which showed the body of a trishaw driver still upright after his legs had been blown off. This photograph was reproduced in an American propaganda magazine published in Manila over the title 'The work of Ho Chi Minh', although General The had promptly and proudly claimed the bomb as his own. Who had supplied the material to a bandit who was fighting French, Caodaists and Communists? There was certainly evidence of contacts between the American services and General The. A jeep with the bodies of two American women was found by a French rubber planter on the route to the sacred mountain - presumably they had been killed by the Viet Minh, but what were they doing on the plantation? The bodies were promptly collected by the American Embassy, and nothing more was heard of the incident. Not a word appeared in the Press. An American consul was arrested late at night on the bridge to Dakow [DaKao ?], (where Pyle in my novel lost his life) carrying plastic bombs in his car. Again the incident was hushed up for diplomatic reasons.

So the subject of The Quiet American came to me, during that talk of a 'third force' on the road through the delta, and my characters quickly followed, all but one of them from the unconscious. The exception was Granger, the American newspaper correspondent. The press conference in Hanoi where he figures was recorded almost word for word in my journal at the time. Perhaps there is more direct reportage in The Quiet American than in any other novel I have written. I had determined to employ again the experience I had gained with The End of the Affair in the use of the first person and the time-shift, and my choice of a journalist as the 'I' seemed to me to justify the use of reportage. The press conference is not the only example of direct reporting. I was in the dive-bomber (the pilot had broken an order of General de Lattre by taking me) which attacked the Viet Minh post and I was on the patrol of the Foreign Legion paras outside Phat Diem. I still retain the sharp image of the dead child couched in the ditch beside his dead mother. The very neatness of their bullet wounds made their death more disturbing than the indiscriminate massacre in the canals around.

I went back to Indo-China for the fourth and last time in 1955 after the defeat of the French in the north, and with some difficulty I reached Hanoi - a sad city, abandoned by the French where I drank the last bottle of beer left in the cafe which I used to frequent with Monsieur Dupont. I was feeling very ill and tired and depressed. I sympathized with the victors, but I sympathized with the French too. The French classics were yet on view in a small secondhand bookshop which Monsieur Dupont had rifled a few years back, but a hundred years of French civilization had fled with the Catholic peasants to the south. The Metropole Hotel where I used to stay was in the hands of the International Commission. Viet Minh sentries stood outside the building where de Lattre had made his promise, 'I leave you my wife as a symbol that France will never, never ... '

Day after day passed while I tried to bully my way into the presence of Ho Chi Minh. It was the period of the crachin and my spirits sank with the thin day-long drizzle of warm rain. I told my contacts I could wait no longer - tomorrow I would return to what was left of French territory in the north.

I don't know why my blackmail succeeded, but I was summoned suddenly to take tea with Ho Chi Minh, and now I felt too ill for the meeting. There was only one thing to be done. I went back to an old Chinese chemist's shop in the rue des Voiles which I had visited the year before. The owner, it was said, was 'the Happiest Man in the World'. There I was able to smoke a few pipes of opium while the mah-jong pieces rattled like gravel on a beach. I had a passionate desire for the impossible - a bottle of Eno's. A messenger was dispatched and before the pipes were finished I received the impossible. I had drunk the last bottle of beer in Hanoi. Was this the last bottle of Eno's? Anyway the Eno's and the pipes took away the sickness and the inertia and gave me the energy to meet Ho Chi Minh at tea.

Of those four winters which I passed in Indo-China opium has left the happiest memory, and as it played an important part in the life of Fowler, my character in The Quiet American, I add a few memories from my journal concerning it, for I am reluctant to leave Indo-China for ever with only a novel to remember it by.

31 December 1953. Saigon

One of the interests of far places is 'the friend of friends': some quality has attracted somebody you know, will it also attract yourself? This evening such a one came to see me, a naval doctor. After a whisky in my room, I drove round Saigon with him, on the back of his motorcycle, to a couple of opium fumeries. The first was a cheap one, on the first floor over a tiny school where pupils were prepared for 'le certificat et le brevet'. The proprietor was smoking himself: a malade imaginaire dehydrated by his sixty pipes a day. A young girl asleep, and a young boy. Opium should not be for the young, but as the Chinese believe for the middle-aged and the old. Pipes here cost 10 piastres each (say 2s.). Then we went on to a more elegant establishment - Chez Pola. Here one reserves the room and can bring a companion. A great Chinese umbrella over the big circular bed. A bookshelf full of books beside the bed - it was odd to find two of my own novels in a fumerie: Le Ministère de la Peur, and Rocher de Brighton. I wrote a dédicace in each of them. Here the pipes cost 30 piastres.

My experience of opium began in October 1951 when I was in Haiphong on the way to the Baie d' Along. A French official took me after dinner to a small apartment in a back street - I could smell the opium as I came up the stairs. It was like the first sight of a beautiful woman

Ways of escape

Cái cú bom nổ trên đường Catinat, mặc dù Mẽo nói, đây là tác phẩm của Bác Hồ, nhưng theo Greene, TMT hãnh diện tự nhận là tác giả.

Cái cú Greene blackmail Bác Hồ mà chẳng thú sao?

Nhưng thú nhất, có lẽ là những xen G. đi hít tô phe, và có lần thấy sách của mình ở tiệm hút, bèn lôi ra, viết lời đề tặng.

Ui chao, giá mà Gấu cũng có tí kỷ niệm này thì thật tuyệt. Tưởng tượng không thôi, vô một tiệm ở Cây Da Xà, thấy Những Ngày Ở Sài Gòn, trên giá sách, kế bên bàn đèn, là đã thấy sướng mê tơi rồi!

*

31 December 1953. Saigon

One of the interests of far places is 'the friend of friends': some quality has attracted somebody you know, will it also attract yourself? This evening such a one came to see me, a naval doctor. After a whisky in my room, I drove round Saigon with him, on the back of his motorcycle, to a couple of opium fumeries. The first was a cheap one, on the first floor over a tiny school where pupils were prepared for 'le certificat et le brevet'. The proprietor was smoking himself: a malade imaginaire dehydrated by his sixty pipes a day. A young girl asleep, and a young boy. Opium should not be for the young, but as the Chinese believe for the middle-aged and the old. Pipes here cost 10 piastres each (say 2s.). Then we went on to a more elegant establishment - Chez Pola. Here one reserves the room and can bring a companion. A great Chinese umbrella over the big circular bed. A bookshelf full of books beside the bed - it was odd to find two of my own novels in a fumerie: Le Ministère de la Peur, and Rocher de Brighton. I wrote a dédicace in each of them. Here the pipes cost 30 piastres.

My experience of opium began in October 1951 when I was in Haiphong on the way to the Baie d' Along. A French official took me after dinner to a small apartment in a back street - I could smell the opium as I came up the stairs. It was like the first sight of a beautiful woman with whom one realizes that a relationship is possible: somebody whose memory will not be dimmed by a night's sleep.

The madame decided that as I was a debutant I must have only four pipes, and so I am grateful to her that my first experience was delightful and not spoiled by the nausea of over-smoking. The ambiance won my heart at once - the hard couch, the leather pillow like a brick these stand for a certain austerity, the athleticism of pleasure, while the small lamp glowing on the face of the pipe-maker, as he kneads his little ball of brown gum over the flame until it bubbles and alters shape like a dream, the dimmed lights, the little chaste cups of unsweetened green tea, these stand for the' luxe et volupte'.

Each pipe from the moment the needle plunges the little ball home and the bowl is reversed over the flame lasts no more than a quarter of a minute - the true inhaler can draw a whole pipeful into his lungs in one long inhalation. After two pipes I felt a certain drowsiness, after four my mind felt alert and calm - unhappiness and fear of the future became like something dimly remembered which I had thought important once. I, who feel shy at exhibiting the grossness of my French, found myself reciting a poem of Baudelaire to my companion, that beautiful poem of escape, Invitation au Voyage. When I got home that night I experienced for the first time the white night of opium. One lies relaxed and wakeful, not wanting sleep. We dread wakefulness when our thoughts are disturbed, but in this state one is calm - it would be wrong even to say that one is happy - happiness disturbs the pulse. And then suddenly without warning one sleeps. Never has one slept so deeply a whole night-long sleep, and then the waking and the luminous dial of the clock showing that twenty minutes of so-called real time have gone by. Again the calm lying awake, again the deep brief all-night sleep. Once in Saigon after smoking I went to bed at 1.30 and had to rise again at 4.00 to catch a bomber to Hanoi, but in those less three hours I slept all tiredness away.

Not that night, but many nights later, I had a curiously vivid dream. One does not dream as a rule after smoking, though sometimes one wakes with panic terror; one dreams, they say, during disintoxication, like de Quincey, when the mind and the body are at war. I dreamed that in some intellectual discussion I made the remark, 'It would have been interesting if at the birth of Our Lord there had been present someone who saw nothing at all,' and then, in the way that dreams have, I was that man. The shepherds were kneeling in prayer, the Wise Men were offering their gifts (I can still see in memory the shoulder and red-brown robe of one of them - the Ethiopian), but they were praying to, offering gifts to, nothing - a blank wall. I was puzzled and disturbed. I thought, 'If they are offering to nothing, they know what they are about, so I will offer to nothing too,' and putting my hand in my pocket I found a gold piece with which I had intended to buy myself a woman in Bethlehem. Years later I was reading one of the gospels and recognized the scene at which I had been an onlooker . “So they were offering their gifts to the mother of God,” I thought. 'Well, I brought that gold piece to Bethlehem to give to a woman, and it seems I gave it to a woman after all.'

10 January 1954. Hanoi

With French friends to the Chinese quarter of Hanoi. We called first for our Chinese friend living over his warehouse of dried medicines from Hong Kong - bales and bales and bales of brittle quackery. The family were all gathered in one upper room with the dog and the cat - husband and wife, daughters, grandparents, cousins. After a cup of tea we paid a visit to a relative - variously known as Serpent Head and the Happiest Man in the World. All these Chinese houses have little frontage, but run back a long way from the street. The Happiest Man in the World sat there between the narrow walls like a tunnel, in thin pajamas - he never troubled to dress. He was rich and he had inherited the business from his father before it was necessary for him to work and when his sons were already old enough to do the work for him. He was like a piece of dried medicine himself, skeletonized by opium. In the background the mah-jong players built their walls, demolished, reshuffled. They didn't even have to look at the pieces they drew, they could tell the design by a touch of the finger. The game made a noise like a stormy tide turning the shingle on a beach. I smoked two pipes as an aperitif, and after dinner at the New Pagoda returned and smoked five more.

11 January 1954. Hanoi

Dinner with French friends and afterwards smoked six pipes. Gunfire and the heavy sound of helicopters low over the roofs bringing the wounded from - somewhere. The nearer you are to war, the less you know what is happening. The daily paper in Hanoi prints less than the daily paper in Saigon, and that prints less than the papers in Paris. The noise of the helicopters had an odd effect on opium smoking. It drowned the soft bubble of the wax over the flame, and because the pipe was silent, the opium seemed to lose a great deal of its perfume, in the way that a cigarette loses taste in the open air.

12 January 1954. Vientiane

Up early to catch a military plane to Vientiane, the administrative capital of Laos. The plane was a freighter with no seats. I sat on a packing case and was glad to arrive.

After lunch I made a rapid tour of Vientiane. Apart from one pagoda and the long sands of the Mekong river, it is an uninteresting town consisting only of two real streets, one European restaurant, a club, the usual grubby market where apart from food there is only the debris of civilization - withered tubes of toothpaste, shop-soiled soaps, pots and pans from the Bon Marche. Fishes were small and expensive and covered with flies. There were little packets of dyed sweets and sickly cakes made out of rice colored mauve and pink. The fortune-maker of Vientiane was a man with a small site let out as a bicycle park - hundreds of bicycles at 2 piastres a time (say 20 centimes). When he had paid for his concession he was likely to make 600 piastres a day profit (say 6,000 francs). But in Eastern countries there are always wheels within wheels, and it was probable that the concessionaire was only the ghost for one of the princes.

Sometimes one wonders why one bothers to travel, to come eight thousand miles to find only Vientiane at the end of the road, and yet there is a curious satisfaction later, when one reads in England the war communiqués and the familiar names start from the page - Nam Dinh, Vientiane, Luang Prabang -looking so important temporarily on a newspaper page as though part of history, to remember them in terms of mauve rice cakes, the rat crossing the restaurant floor as it did tonight until it was chased away behind the bar. Places in history, one learns, are not so important.

After dinner to the house of Mr. X, a Eurasian and a habitual smoker. Thinned by his pipes, with bony wrists and ankles and the arms of a small boy, Mr. X was a charming and melancholy companion. He spoke beautifully clear French, peering down at his needle through steel-rimmed spectacles. His house was a hovel too small for him to find room for his wife and child whom he had left in Phnom Penh. There was nothing to do in the evening - the cinema showed only the oldest films, and there was really nothing to do all day either, but wait outside the government office where he was employed on small errands. A palm tree was his bookcase and he would slip his book or his newspaper into the crevices of the trunk when summoned into the house. Once I needed some wrapping paper and he went to the palm tree to see whether he had any saved. His opium was excellent, pure Laos opium, and he prepared the pipes admirably. Soon his French employers would be packing up in Laos, he would go to France, he would have no more opium - all the ease of life would vanish but he was incapable of considering the future. His sad amused Asiatic face peered down at the pipe while his bony fingers kneaded and warmed the brown seed of contentment, and he spoke musically and precisely like a don on the types and years of opium - the opium of Laos, Yunan, Szechuan, Istanbul, Benares - ah, Benares, that was a kind to remember over the years. *

13 January 1954

On again to Luang Prabang. Where Vientiane has two streets Luang Prabang has one, some shops, a tiny modest royal palace (the King is as poor as the state) and opposite the palace a steep hill crowned by a pagoda which contains - so it is believed - the giant footprint of Buddha. Little side streets run down to the Mekong, here full of water. There is a sense of trees, temples, small quiet homes, river and peace. One can see the whole town in half an hour's walk, and one could live here, one feels, for weeks, working, walking, sleeping, if the Viet Minh were not on their way down from the mountains. We determined, tomorrow before returning, to take a boat up the Mekong to the grotto and the statue of Buddha which protects Luang Prabang from her enemies. There is more atmosphere of prayer in a pagoda than in most churches. The features of Buddha cannot be sentimentalized like the features of Christ, there are no hideous pictures on the wall, no stations of the Cross, no straining after unfelt agonies. I found myself praying to Buddha as always when I enter a pagoda, for now surely he is among our saints and his intercession will be as powerful as the Little Flower's - perhaps more powerful here among a race akin to his own.

After dinner I was very tired, but five pipes of inferior opium - bitter with dross - smoked in a chauffeur's house made me feel fresh again. It was a house on piles and at the end of the long narrow veranda, screened from the dark and the mosquitoes, a small son knelt at a table doing his lessons while his mother squatted beside him. The soft recitation of his lesson accompanied the murmur and the bubble of the pipe.

16 January 1954. Saigon .

Laos remained careless Laos till the end. f was worried by the late arrival of the car and only just caught the plane which left the airfield at 7.00 in the dark. Two stops on the way to Saigon. I got in about 12.30. Why is it that Saigon is always so good to come back to? I remember on my first journey to Africa, when I walked across Liberia, I used to dream of the delights of a hot bath, a good meal, a comfortable bed. I wanted to go straight from the African hut with the rats

One of the interests of far places is 'the friend of friends': some quality has attracted somebody you know, will it also attract yourself? This evening such a one came to see me, a naval doctor. After a whisky in my room, I drove round Saigon with him, on the back of his motorcycle, to a couple of opium fumeries. The first was a cheap one, on the first floor over a tiny school where pupils were prepared for 'le certificat et le brevet'. The proprietor was smoking himself: a malade imaginaire dehydrated by his sixty pipes a day. A young girl asleep, and a young boy. Opium should not be for the young, but as the Chinese believe for the middle-aged and the old. Pipes here cost 10 piastres each (say 2s.). Then we went on to a more elegant establishment - Chez Pola. Here one reserves the room and can bring a companion. A great Chinese umbrella over the big circular bed. A bookshelf full of books beside the bed - it was odd to find two of my own novels in a fumerie: Le Ministère de la Peur, and Rocher de Brighton. I wrote a dédicace in each of them. Here the pipes cost 30 piastres.

My experience of opium began in October 1951 when I was in Haiphong on the way to the Baie d' Along. A French official took me after dinner to a small apartment in a back street - I could smell the opium as I came up the stairs. It was like the first sight of a beautiful woman with whom one realizes that a relationship is possible: somebody whose memory will not be dimmed by a night's sleep.

The madame decided that as I was a debutant I must have only four pipes, and so I am grateful to her that my first experience was delightful and not spoiled by the nausea of over-smoking. The ambiance won my heart at once - the hard couch, the leather pillow like a brick these stand for a certain austerity, the athleticism of pleasure, while the small lamp glowing on the face of the pipe-maker, as he kneads his little ball of brown gum over the flame until it bubbles and alters shape like a dream, the dimmed lights, the little chaste cups of unsweetened green tea, these stand for the' luxe et volupte'.

Each pipe from the moment the needle plunges the little ball home and the bowl is reversed over the flame lasts no more than a quarter of a minute - the true inhaler can draw a whole pipeful into his lungs in one long inhalation. After two pipes I felt a certain drowsiness, after four my mind felt alert and calm - unhappiness and fear of the future became like something dimly remembered which I had thought important once. I, who feel shy at exhibiting the grossness of my French, found myself reciting a poem of Baudelaire to my companion, that beautiful poem of escape, Invitation au Voyage. When I got home that night I experienced for the first time the white night of opium. One lies relaxed and wakeful, not wanting sleep. We dread wakefulness when our thoughts are disturbed, but in this state one is calm - it would be wrong even to say that one is happy - happiness disturbs the pulse. And then suddenly without warning one sleeps. Never has one slept so deeply a whole night-long sleep, and then the waking and the luminous dial of the clock showing that twenty minutes of so-called real time have gone by. Again the calm lying awake, again the deep brief all-night sleep. Once in Saigon after smoking I went to bed at 1.30 and had to rise again at 4.00 to catch a bomber to Hanoi, but in those less three hours I slept all tiredness away.

Not that night, but many nights later, I had a curiously vivid dream. One does not dream as a rule after smoking, though sometimes one wakes with panic terror; one dreams, they say, during disintoxication, like de Quincey, when the mind and the body are at war. I dreamed that in some intellectual discussion I made the remark, 'It would have been interesting if at the birth of Our Lord there had been present someone who saw nothing at all,' and then, in the way that dreams have, I was that man. The shepherds were kneeling in prayer, the Wise Men were offering their gifts (I can still see in memory the shoulder and red-brown robe of one of them - the Ethiopian), but they were praying to, offering gifts to, nothing - a blank wall. I was puzzled and disturbed. I thought, 'If they are offering to nothing, they know what they are about, so I will offer to nothing too,' and putting my hand in my pocket I found a gold piece with which I had intended to buy myself a woman in Bethlehem. Years later I was reading one of the gospels and recognized the scene at which I had been an onlooker . “So they were offering their gifts to the mother of God,” I thought. 'Well, I brought that gold piece to Bethlehem to give to a woman, and it seems I gave it to a woman after all.'

10 January 1954. Hanoi

With French friends to the Chinese quarter of Hanoi. We called first for our Chinese friend living over his warehouse of dried medicines from Hong Kong - bales and bales and bales of brittle quackery. The family were all gathered in one upper room with the dog and the cat - husband and wife, daughters, grandparents, cousins. After a cup of tea we paid a visit to a relative - variously known as Serpent Head and the Happiest Man in the World. All these Chinese houses have little frontage, but run back a long way from the street. The Happiest Man in the World sat there between the narrow walls like a tunnel, in thin pajamas - he never troubled to dress. He was rich and he had inherited the business from his father before it was necessary for him to work and when his sons were already old enough to do the work for him. He was like a piece of dried medicine himself, skeletonized by opium. In the background the mah-jong players built their walls, demolished, reshuffled. They didn't even have to look at the pieces they drew, they could tell the design by a touch of the finger. The game made a noise like a stormy tide turning the shingle on a beach. I smoked two pipes as an aperitif, and after dinner at the New Pagoda returned and smoked five more.

11 January 1954. Hanoi

Dinner with French friends and afterwards smoked six pipes. Gunfire and the heavy sound of helicopters low over the roofs bringing the wounded from - somewhere. The nearer you are to war, the less you know what is happening. The daily paper in Hanoi prints less than the daily paper in Saigon, and that prints less than the papers in Paris. The noise of the helicopters had an odd effect on opium smoking. It drowned the soft bubble of the wax over the flame, and because the pipe was silent, the opium seemed to lose a great deal of its perfume, in the way that a cigarette loses taste in the open air.

12 January 1954. Vientiane

Up early to catch a military plane to Vientiane, the administrative capital of Laos. The plane was a freighter with no seats. I sat on a packing case and was glad to arrive.