January 1 1965

Noel Chez Nous

Old & New Home

NYRB Jan, 2000

Bài thơ này, được viết khi Brodsky bị lưu đầy nội xứ, ở 1 nông trại ở phiá Bắc nước Nga.

Ở Nga, lễ mừng năm mới được coi như lễ mừng Giáng Sinh.

Bản dịch tiếng Anh, của chính tác giả, được kiếm thấy trong những giấy tờ của ông.

Những Vì Vua sẽ đánh mất những địa chỉ cũ của mi

Không một vì sao sẽ sáng lên nhằm tạo ấn tượng.

Tai của mi bèn chịu thua

Tiếng hú gào nhức nhối của những trận bão.

Cái bóng của mi

Bèn rụng rời, bye bye, cái lưng của mi

Mi bèn tắt đèn cầy, và bèn đụng cái bao tải

Bởi là vì mi còn phải bóc lịch dài dài,

Ở cái nông trường cải tạo Đỗ Hoà, Nhà Bè này

Bao nhiêu đèn cày cho đủ,

Cho những cuộc…. đốt đuốc chơi đêm?

Cái gì, cái này?

Nỗi buồn ư?

Nhớ Xề Gòn ư?

Nhớ mấy đứa nhỏ ư?

Đúng rồi, có lẽ nó, đấy,

Một khúc nhạc sến sẽ chẳng bao giờ ngưng

Cái gì gì,

Ngọn đèn đêm đứng im, “cuối” đầu!

Lũ Ngụy gần như thuộc nằm lòng, những khúc trầm bổng

Cầu cho nó được chơi rất đúng tông, cùng với những điều sắp tới

Với góc khuất của một ai đó

Bằng sự biết ơn, của mắt và của môi

Về những gì cho chúng biết,

Làm sao xoay sở

Về 1 điều xa xưa

Những ngày tháng cũ.

Và bèn ngước mắt nhìn lên, nơi không một đám mây trôi giạt

Bởi là vì mi cạn láng đời rồi, Gấu ơi là Gấu ơi.

Mi sẽ hiểu, tiện tặn nghĩa là gì:

Nó hợp với tuổi của mi.

Không phải 1 sự coi thường.

Quá trễ rồi, cho đột phá

Dành cho những phép lạ

Dành cho Ông Già Noel và bầy đoàn thê tử của Xừ Lủy

Và bất thình lình mi hiểu ra được

Mi, chính mi, là Phép Lạ

Hay, khiêm tốn hơn,

Một món quà triệt để, dứt khoát.

Joyeux Noel 2017

From California

Dec 16 at 12:51 AM

Dear Gấu Nhà Văn,

Wishing you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

Best regards,

Seagull.

Tks

Take Care

Joyeux Noel to U & Family

NQT

Old & New Home

NYRB Jan, 2000

Bài thơ này, được viết khi Brodsky bị lưu đầy nội xứ, ở 1 nông trại ở phiá Bắc nước Nga.

Ở Nga, lễ mừng năm mới được coi như lễ mừng Giáng Sinh.

Bản dịch tiếng Anh, của chính tác giả, được kiếm thấy trong những giấy tờ của ông.

Ngày 1 Tháng Giêng, 1965

Những Vì Vua sẽ đánh mất những địa chỉ cũ của mi

Không một vì sao sẽ sáng lên nhằm tạo ấn tượng.

Tai của mi bèn chịu thua

Tiếng hú gào nhức nhối của những trận bão.

Cái bóng của mi

Bèn rụng rời, bye bye, cái lưng của mi

Mi bèn tắt đèn cầy, và bèn đụng cái bao tải

Bởi là vì mi còn phải bóc lịch dài dài,

Ở cái nông trường cải tạo Đỗ Hoà, Nhà Bè này

Bao nhiêu đèn cày cho đủ,

Cho những cuộc…. đốt đuốc chơi đêm?

Cái gì, cái này?

Nỗi buồn ư?

Nhớ Xề Gòn ư?

Nhớ mấy đứa nhỏ ư?

Đúng rồi, có lẽ nó, đấy,

Một khúc nhạc sến sẽ chẳng bao giờ ngưng

Cái gì gì,

Ngọn đèn đêm đứng im, “cuối” đầu!

Lũ Ngụy gần như thuộc nằm lòng, những khúc trầm bổng

Cầu cho nó được chơi rất đúng tông, cùng với những điều sắp tới

Với góc khuất của một ai đó

Bằng sự biết ơn, của mắt và của môi

Về những gì cho chúng biết,

Làm sao xoay sở

Về 1 điều xa xưa

Những ngày tháng cũ.

Và bèn ngước mắt nhìn lên, nơi không một đám mây trôi giạt

Bởi là vì mi cạn láng đời rồi, Gấu ơi là Gấu ơi.

Mi sẽ hiểu, tiện tặn nghĩa là gì:

Nó hợp với tuổi của mi.

Không phải 1 sự coi thường.

Quá trễ rồi, cho đột phá

Dành cho những phép lạ

Dành cho Ông Già Noel và bầy đoàn thê tử của Xừ Lủy

Và bất thình lình mi hiểu ra được

Mi, chính mi, là Phép Lạ

Hay, khiêm tốn hơn,

Một món quà triệt để, dứt khoát.

Joyeux Noel 2017

From California

Dec 16 at 12:51 AM

Dear Gấu Nhà Văn,

Wishing you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

Best regards,

Seagull.

Tks

Take Care

Joyeux Noel to U & Family

NQT

-

Comments

- Khanh Huynh Phải, Chính Gấu làm phép lạ, cho những lời thơ phục sinh từ nấm mộ Siberia, từ trại tập trung không tên ngay xứ sở của mình, bằng ngọn nến giáng sinh của Chúa Hài đồng, thổi, ấm mùa đông bằng những ngôn từ đánh dấu từ buổi Ba- bên.

- Khanh Huynh Bác cho cháu share nhé.

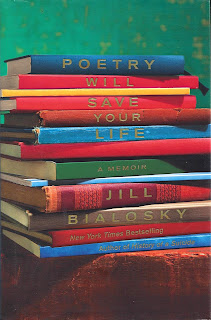

Note: Trong cuốn Thơ Kíu Đời, tác giả xếp bài thơ của

Brodsky vào mục Family, và lèm bèm tới chỉ về nó, cùng với bài thơ của Rilke.

Post sau đây

FAMILY

JANUARY 1, 1

965

Joseph

Brodsky

CHILDHOOD

Rainer Maria

Rilke

Old-world

traits such as modesty, fear of standing out, insecurity, and distrust are part

of my inheritance from my mother's ancestors, who grew up in Eastern Europe and

immigrated to America. After World War I and the mass exodus of emigration, the

children of immigrants in Cleveland, like in other cities in America,

eventually moved up into the middle class, creating new institutions-synagogue

centers, progressive Hebrew schools, Jewish community centers-attempting to assimilate

and Americanize while at home there still lingered a feeling of difference. My

great aunts and grandparents referred to anyone who wasn't Jewish as a Gentile.

You were one or the other. There was a hierarchy among Jewish immigrant

families. Men worked in the garment districts, or as tailors or peddlers; my

paternal grandfather opened a pawn shop, my mother's father worked as a bank

teller; women prepared the meals and took care of the children; and children were

coddled. Fear lurked over our shoulders. Fear that history would repeat itself

and all our ancestors had built, if they were not cautious, would be taken

away.

I too am raised in this atmosphere of stuffy seclusion and distrust.

All the rooms in my grandfather's house, where we go every Friday night for

Shabbat, seem too small. There are doilies on the cherry wood tables that slip

off if I lean on them. Prayer books, antique clocks, and tchotchkes from the old

country don the shelves, mantles, and walls. I'm afraid I'll break something if

I'm not careful. Sometimes around my relatives I can't breathe. My maternal

great aunts are protective of us. They worry in the winter when we come to see them

that we are not dressed warmly enough. They worry about the crosswalk across

the street from our school and whether we'll get run down if we don't carefully

look both ways. They think we are too thin or too plump. Protectiveness breeds

fear and distrust. Being raised without a father perpetuates this fear. There

is always the sense that instability and ruin are right around the corner. I am

aware that being Jewish makes me different and am grateful that my face is not

marked by typical Jewish features: big nose and kinky hair.

Once on Passover, I notice an extra place set at the table and

a goblet of wine later poured, though no one drank it. At first I think that it

is for a guest who has not arrived and then I think to myself maybe my father

hasn't died at all, maybe it has all been a terrible lie or a trick and this

cup of wine is for him and soon he will be home. My imagination runs wild. Later,

in Hebrew school, I learn that the common tradition at a Seder is to have an

empty cup for the prophet Elijah, which, at the end of the Seder, is filled

with wine. During the Passover Seder we recount in the Haggadah the redemption

of the Jews from Egypt and also express our hope for future redemption with the

coming of the Messiah. The tradition is that Elijah the prophet, in his

eventual coming, will be the one to announce the coming of the Messiah. No

matter. In my mind, my father has become my own Jewish prophet. One day he will

come. I am sure of it.

At the table we listen to the grown-ups talk while feeling squirrely

in our creaky, wooden fold-up chairs, overheated from the cooking of brisket

and potatoes that hangs heavy in the air. One uncle talks about a friend who

was overlooked for a promotion because he was Jewish. My aunt won't serve the

challah because my grandfather bought it at the grocery store instead of the

Jewish bakery. "Is he Jewish?" another aunt prods my mother when she

speaks about someone new she is dating. For my thirteenth birthday, I am given a

gold Jewish star necklace as a present but I'm afraid to wear it outside my

shirt. I don't quite understand the obsession with being Jewish. It seems to be

a blessing and a curse.

At school, I don't like being the object of other people's attention.

I don't know how to talk to adults. I bury my head in my books and rarely raise

my hand or speak unless I am called on. In this way, I learn how easy and more comfortable

it is to slip below the radar of authority. I don't trust teachers or adults in

general. If a teacher speaks to me or gives me attention, no matter how kind, I

read pity in her eyes. Pity to have lost a father, pity to have to write a card

to her grandfather instead of her father for Father's Day. Pity morphs into a lack

of trust. If a teacher praises an essay or paper I write, I can't take in the

praise, and instead tell myself he or she just feels sorry for me. It's not a

great way of being, but I don't know how to be anyone else. Why am I this way?

Why this fear of stepping out? Of being known? This fear of happiness? Like

many girls my age, I eventually read The Diary of Anne Frank and her story

makes my blood run cold. I think how lucky she is to have been in seclusion,

not just with her family but with Peter's family, and I am eager to skip to the

parts in the diary where I anticipate Anne and Peter will have their first

kiss. But, mostly, each page I turn leaves me with a pit in my stomach. Will

this legacy of fear and hiding repeat itself?

JANUARY 1, 1965

Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996)

The kings

will lose your old address.

No star will

flare up to impress.

The ear may

yield, under duress,

to

blizzards' nagging roar.

The shadows

falling off your back,

you'd snuff

the candle, hit the sack,

for

calendars more nights can pack

than there

are candles for.

What is

this? Sadness? Yes, perhaps.

A little

tune that never stops.

One knows by

heart its downs and ups.

May it be

played on par

with things

to come, with one's eclipse,

as

gratefulness of eyes and lips

for what

occasionally keeps

them trained

on something far.

And staring

up where no cloud drifts

because your

sock's devoid of gifts

you'll

understand this thrift: it fits

your age;

it's not a slight.

It is too

late for some breakthrough,

for

miracles, for Santa's crew.

And suddenly

you'll realize that you

yourself are

a gift outright.

****

The more I

read the poem, the further I read into it my own inheritance. "What is

this? Sadness?" this poem asks. It is a poem of exile, opening with images

of the Wise Men, the Kings who have forgotten one's address and a star, perhaps

the Jewish Star of David or Shield of David, with its hexagram shape that dates

to the seventeenth century, "that will not flare up to impress."

Joseph Brodsky, born a Russian Jew and once a lauded poet in his homeland, was

eventually persecuted for his fiery and individualistic poetry that challenged

Soviet ideals. After standing trial for "parasitism" he was forced to

live in a hard labor camp and then a mental institution until American

intellectuals helped get him released. He came to America in 1972 with the help

of the poet W. H. Auden to teach at the University of Michigan.

"January 1, 1965" was written while Brodsky was in

internal exile enduring hard labor in Norenskaia, in the Arkhangelsk region of

northern Russia. In the Soviet Union, New Year's celebrations came to be seen

as a substitute for Christmas. Every year, Brodsky wrote a new year's poem. "January

1, 1965" acknowledges the passing of time as represented in the opening

stanza by the image of candles, the calendar, and the lurking fear of death. It

contains allusions of oppression and persecution. Tones of resignation reverberate;

the poet is too old to celebrate "Santa" and believe in miracles. His

stockings are empty. "Devoid of gifts." Ironically, Brodsky was only

twenty-four when he wrote the poem. Even with its defiant note in the last

line, "you realize you yourself are a gift outright," the futility of

escaping history is omnipresent. Though my ancestors were not exiled in this way,

the aftershocks of being born a Jew and the legacy of oppression were part of

my historical inheritance.

We rarely know how or why certain events and experiences

shape us in childhood or the way in which we absorb the atmosphere in ways that

linger.

Comments

Post a Comment