THE DWARF PINE

THE DWARF PINE

Cây thông lùn

Ở vùng cực bắc, nơi rừng taiga gặp vùng đất tundra [lãnh nguyên] không cây cối, giữa những bụi lu lô lùn, những bụi thanh lương chậm lớn, với những bụi trứng cá vàng chói, mọng nước, rộng lớn một cách lạ thường của chúng, và những cây thông tuổi thọ sáu trăm năm (chúng đạt độ trưởng thành khi được ba tram năm), có 1 thứ cây đặc biệt, cây thông lùn. Nó có họ hàng xa với cây cedar [tuyết tùng] Siberian hay thông, 1 thứ vạn niên thanh với thân cây dầy hơn tay người, và dài ba hoặc bốn mét. Nó chẳng thèm để ý đến chuyện mọc lên ở chỗ nào, rễ của nó bám kẽ đá nơi sườn núi. Nó thật là đàn ông, và thật là cứng đầu, như tất cả những cây cối miền bắc. Mẫn tính của nó mới thật là kỳ dị, khác thường.

Đó là vào lúc cuối thu, tuyết và mùa đông thì trễ hẹn, quá trễ hẹn. Trong nhiều ngày có những đám mây thấp, mầu xanh lợt, di chuyển ở nơi mép bờ đường chân trời trắng: mây bão nhìn như thể chúng được bao phủ bởi những vết thâm. Bữa sáng nay, gió thu sắc bén trở nên êm ả quá đỗi lạ thường. Dấu báo của tuyết chăng? Không, chẳng tí tuyết. Cây thông lùn chưa có rạp xuống, chưa biến mất. Ngày qua ngày, vưỡn chưa có tuyết, và những cụm mây nặng nề lang thang đâu đó ở đằng sau những ngọn đồi trần trụi, trong khi đấng mặt trời nhợt nhạt đã bò ra, ở trên bầu trời cao, và tất cả ba thứ lẻ lẻ như thế cho biết, vưỡn còn mùa thu.

Và rồi cây lùn gập người. Nó gập người thấp, thấp nữa, như dưới 1 sức nặng, nặng ơi là nặng, nặng như chưa từng nặng như thế, mỗi lúc một tăng. Cái đỉnh cây, hay, cái vương miện của nó cào gãi khối đá, co cưỡng lại mặt đất, như mọc ra những chân cẳng, nanh vuốt. Nó đang làm cái giường của nó. Nó giống như 1 con mực trong bộ lông xanh.

Một khi nằm xuống, nó đợi 1, hay 2 ngày, và bây giờ bầu trời trắng trao gửi, phân phát một cơn mưa nhẹ tuyết, giống như bột, và cây thông lùn bèn chúi vô giấc ngủ đông, như 1 con gấu.

Những khối tuyết khổng lồ như những vết bỏng cuồn cuộn cuốn mãi lên tới ngọn núi trắng: Những bụi thông lùn trong giấc ngủ mùa đông của nó.

Khi mùa đông chấm dứt, tuy vẫn còn một lớp tuyết dày chừng ba thước phủ mặt đất, trong những rãnh nước, những cơn bão đã nén tuyết chặt cứng, chỉ 1 thứ dụng cụ bằng sắt mới có thể lay chuyển nó, con người bèn tìm kiếm coi có cái gì có mùi xuân chưa, nhưng vô ích. Tờ lịch phán, đến rồi mà, đây là thời gian lớn để cho nó tới, nhưng ngày vẫn ngày vẫn như mùa đông còn dài dài. Bầu trời, không gian, khí trời thì loãng, và khô, y chang Tháng Giêng. Thật phúc đức, bởi là vì con người, chúng vốn suy tư theo kiểu quá thô, và cảm nhận của chúng thì thật là hoang sơ, [cứ như từ hang Pác Bó bò ra]. Nói gì thì nói, con người chỉ có những giác quan, nào sờ, nào mó, nào ngửi nào hít, ba cái trò đó, không đủ để tiên đoán, hay trực giác, linh giác cái con mẹ gì hết.

Cảm xúc của thiên nhiên tế vi hơn nhiều. Con người biết điều này, tới một mức nào đó. Bạn có nhớ giống cá hồi, đi mãi đâu đâu, lưu vong xó xỉnh nào, thì cũng lần về được khúc sông chúng đã từng đẻ trứng? Bạn có nhớ bầy chim bỏ xứ, và những con đường chúng bí ẩn mà chúng lần ra được để mà trở về? Có những cây cỏ, hoa lá xử sự như những thời khắc biểu?

Và cũng thế là loài thông lùn mọc lên giữa những vùng tuyết hoang, vô vọng tràn đầy. Nó lắc thân mình, rũ tuyết, và cứ thế, thẳng đứng vươn tới chiều cao của nó, giương những chiếc lá như những mũi kim, xanh, hơi hồng, phủ băng giá, lên trời cao. Nó có thể cảm, điều chúng ta không thể: tiếng gọi của mùa xuân. Tin vào mùa xuân, nó mọc lên trước hết, trước hết cả mọi người ở miền bắc. Mùa Đông hết rồi.

Nó còn mọc lên cho nhiều lý do khác nữa, 1 ngọn lửa mừng, thí dụ. Cây thông lùn mới đáng tin cậy làm sao. Nó không ưa mùa đông 1 tí nào, và thế là nó bèn tin ở sức nóng của lửa. Nếu bạn đốt lửa vào mùa đông kế bên một bụi thông lùn rũ rượu, quăn queo, ù lì… nó bèn tỉnh dậy. Khi lửa tàn, cây thông, mất mẹ hết ảo tượng, sụt sùi trong thất vọng, lại rũ xuống và nằm thườn thượt vào chỗ cũ, và tuyết lại phủ nó.

Không, không chỉ là báo tin thời tiết. Cây thông lùn còn là cây của hy vọng, thứ cây vạn niên thanh độc nhất của miền Cực Bắc. Chống lại tuyết trắng, chân cẳng nanh vuốt của nó nói về miền nam, cái ấm, cái áp, cuộc đời. Vào mùa hè, mấy thứ của hiếm đó không được để ý tới. Tất cả thi nhau nở rộ, hăm hở, vội vã, trong khoảng ngắn ngủi của mùa hè miền bắc. Mùa xuân, mùa hạ, và mùa thu hoa lá thi nhau chạy đua, trong 1 cơn khùng điên ba trợn, trong một thời gian, kể như là 1 mùa. Nhưng mùa thu thì cận kề, và cây thông bị vặt trụi, như muốn né tránh những chiếc lá nhọn hoắt, vàng 1 một màu, một cõi; cỏ nâu, sáng, cuộn mình lại rồi khô mãi đi, rừng trở thành trống rỗng, và thế là bạn có thể nhìn thấy từ xa, những đỉnh, những chop thông lùn khổng lồ, màu xanh, sáng rực như lửa trong khu rừng, giữa cỏ vàng nhợt, và rêu xám.

Tôi thường nghĩ thông lùn là thứ cây thơ mộng nhất của nước Nga, hơn là coi đây là thứ liễu ưa khóc nhè, ưa nổ, hay 1 thứ cây của 1 miền đồng bằng. hay cây bách. Và củi thông lùn nóng hơn.

****

Note: Trong bài điểm sách trên tờ NYRB, tác giả dành cho cái truyện ngắn chỉ có 1 mẩu những dòng vinh danh quá đỗi thần sầu, và đối với chúng ta, đây là món quà quá đỗi tuyệt vời cho mùa Giáng Sinh năm nay. Gấu sẽ chuyển ngữ trọn vẹn bài điểm sách, và cái truyện ngắn tặng độc giả New Tinvan và FB:

Và như thế đó, cây thông lùn mọc lên giữa những hoang địa vô bờ bến tuyết trắng phủ trùng trùng, giữa tuyệt vô hy vọng. Nó lắc người rũ tuyết thẳng tắp, cao tắp, dâng những cây kim xanh, đo đỏ, phủ băng, lên bầu trời. Nó ngửi ra cái mà con người không thể ngửi ra được: tiếng gọi của mùa xuân. Tin vào mùa xuân, nó mọc lên trước hết, trước hết cả mọi người ở miền bắc. Mùa Đông hết rồi...

[Thông điệp của GCC gửi về nước Mít, thì cứ khùng được lúc nào thì cứ khùng!]

Cây thông lùn là cây của hy vọng, cây vạn niên thanh độc nhất ở vùng Cực Bắc. Chống lại tuyết trắng, chân cẳng nanh vuốt của nó nói về miền nam, cái ấm, cái áp, cuộc đời.

And so the pine dwarf rises amid the boundless white snowy wastes, amid this complete hopelessness. It shakes off the snow, straightens up to its full height, raises its green, ice-covered, slightly reddish needles toward the sky. It can sense what we cannot: the call of spring. Trusting in spring, it rises before anyone else in the north. Winter is over. ...

The dwarf pine is a tree of hope, the only evergreen tree in the Far North. Against the radiant white snow, its matt-green coniferous paws speak of the south, of warmth, of life.

****

THE DWARF PINE

In the far north, where the taiga meets the treeless tundra, among the dwarf birches, the low-growing rowan bushes with their surprisingly large bright yellow, juicy berries, and the six-hundred-year-old larches (they reach maturity at three hundred years), there is a special tree, the dwarf pine. It is a distant relative of the Siberian cedar or pine, an evergreen bush with a trunk that is thicker than a human arm and two or three meters long. It doesn't mind where it grows; its roots will cling to cracks in the rocks on mountain slopes. It is manly and stubborn, like all northern trees. Its sensitivity is extraordinary.

It’s late autumn and snow and winter are long overdue. For many days there have been low, bluish clouds moving along the edge of the white horizon: storm clouds that look as if they are covered in bruises. This morning the piercing autumn wind has turned ominously quiet. Is there a hint of snow? No. There won't be any snow. The dwarf pine hasn’t down yet. Days pass, and still there's no snow and the heavy clouds wander about somewhere behind the bare hills, while a small pale sun has risen, in the high sky, and everything is as it should be in autumn.

Then the dwarf pine bends. It bends lower and lower, as if under an immense ever-increasing weigh. Its crown scratches the rock and huddles against the ground as it stretches out its emerald paws. It is making its bed. It's like an octopus dressed in green feathers. Once it has lain down, it waits a day or two, and now the white sky delivers a shower of snow like powder, and the dwarf pine sinks into hibernation, like a bear. Enormous snowy blisters swell up on the white mountain: the dwarf pine bushes in their winter sleep.

When winter ends, but a three-meter layer of snow still covers the ground and in the gullies the blizzards have compacted the snow so firmly that only an iron tool can shift it, people search nature in vain for any signs of spring. The calendar says that it's high time spring came. But the days are the same as in winter. The air is rarefied and dry, just as it was in January. Fortunately, human senses are too crude and their perceptions too primitive. In any case humans have only their senses, which are not enough to foretell or intuit anything.

Nature's feelings are more subtle. We already know that to some extent. Do you remember the salmon family of fish that come and spawn only in the river where the eggs they hatched from were spawned? Do you remember the mysterious routes taken by migratory birds? There are quite a few plants and flowers known to act as barometers.

And so the dwarf pine rises amid the boundless white snowy wastes amid this complete hopelessness. It shakes off the snow, straight to its full height, raises its green, ice-covered, slightly reddish needles toward the sky. It can sense what we can not: the call of spring. Trusting in spring, it rises before anyone else in the north. Winter is over.

It might rise for other reasons: a bonfire. The dwarf pine is too trusting. It dislikes winter so much that it will trust the heat of a fire. If you light a fire in winter next to a bent, twisted, hibernating dwarf pine bush, it will rise up. When the fire goes out, the disillusioned pine, weeping with disappointment, bends again and lies down where it had been. And snow covers it again.

No, it is not just a predictor of the weather. The dwarf pine is a tree of hope, the only evergreen tree in the Far North. Against the radiant white snow, its matt-green coniferous paws speak of the south of warmth, of life. In summer it is modest and goes unnoticed. Everything around it is hurriedly blooming, trying to blossom during the short northern summer. Spring, summer, and autumn flowers race one another in a single furious stormy flowering season. But autumn is close, and the larch is stripped bare as it scatters its fine, yellow needles; the light-brown grass curls up and withers, the forest is emptied, and then you can see in the distance the enormous green torches of the dwarf pine burning in that forest amid the pale yellow grass and the gray moss.

I always used to think of the dwarf pine as the most poetic Russian tree rather better than the much vaunted weeping willow, the plane tree, or the cypress. And dwarf pine firewood burns hotter.

1960

https://www.nybooks.com/…/12/06/varlam-shalamov-hell-and-b…/

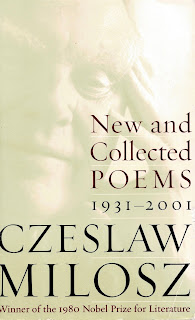

Portrait:

Varlam Shalamov, 1970s

NGƯỜI VỀ

Người về từ cõi ấy

Vợ khóc một đêm con lạ một ngày

Người về từ cõi ấy

Vợ khóc một đêm con lạ một ngày

Người về từ cõi ấy

Bước vào cửa người quen tái mặt

Người về từ cõi ấy

Giữa phố đông nhồn nhột sau gáy

Một năm sau còn nghẹn giữa cuộc vui

Hai năm còn mộng toát mồ hôi

Ba năm còn nhớ một con thạch thùng

Mười năm còn quen ngồi một mình trong tối

Một hôm có kẻ nhìn trân trối

Một đêm có tiếng bâng quơ hỏi

Giật mình,

một cái vỗ vai

Hoàng Hưng

------------------------------------------------

Trong Gulag, có một đoạn Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn tả, về cái cảm giác giữa những người đã từng ở Gulag, và sau đó, được trả về đời. Họ nhận ra nhau ngay, giữa phố đông người. Chỉ ánh mắt gặp nhau, là biết liền đằng ấy và tớ đã từng ở trong đó.

*

Bài thơ của Hoàng Hưng, như được biết, là một trong 100 bài thơ hay. Không hiểu thi sĩ có tiên tri ra được cái sự bí nhiệm của con số hay không, nhưng có vẻ như ông rất quan tâm đến nó, chỉ để "đếm" thời gian: vợ khóc 'một' đêm. con lạ 'một' ngày. Một năm sau còn nghẹn giữa cuộc vui, hai năm sau còn toát mồ hôi. Năm năm, muời năm... một hôm, một đêm...

Liệu tất cả những cân đo đong đếm đó, là để qui chiếu về câu: Nhất nhật tại tù thiên thu tại ngoại?

Câu này, lại trở thành một ẩn dụ, nếu so cảnh tại ngoại của ông, như được miêu tả trong bài thơ:

Có vẻ như cái cảnh trở về đời kia, vẫn chỉ là, tù trong tù.

Tuy nhiên, khi đọc như thế, có vẻ như hạ thấp bài thơ.

Bài thơ Hoàng Hưng bảnh hơn cách đọc đó nhiều. Có cái vẻ thanh thoát, vượt lên trên tất cả của nhà thơ. Đây cũng là điều nhân loại tìm đọc Gulag của Solz: Cái thái độ đạo đức, nhân bản của tác phẩm và của tác giả.

Giọng kể của Solz là một thứ đạo đức kinh của một linh hồn bị đọa đầy tìm mong sự cứu chuộc, mặc khải, tái sinh, "trẻ mãi không già".

Nó đem đến hy vọng.

Câu thơ "Mười năm còn quen ngồi một mình trong bóng tối" làm nhớ một chi tiết về một nhà thơ trong nhóm Nhân Văn, [không nhớ là ai], ông quen ngồi một mình đến nỗi bóng in lên tường, thành một cái vệt, thời gian không làm sao xóa mờ.

Nếu như thế, một người quen ngồi một mình trong bóng tối, cái bóng của người đó in lên tường mới khủng khiếp làm sao.

Không ai có thể nhìn thấy nó, để mà hỏi thử, thời gian, khi nào thì mới xoá... xong!

Nguyễn Quốc Trụ

Bước vào cửa người quen tái mặt

Người về từ cõi ấy

Giữa phố đông nhồn nhột sau gáy

Một năm sau còn nghẹn giữa cuộc vui

Hai năm còn mộng toát mồ hôi

Ba năm còn nhớ một con thạch thùng

Mười năm còn quen ngồi một mình trong tối

Một hôm có kẻ nhìn trân trối

Một đêm có tiếng bâng quơ hỏi

Giật mình,

một cái vỗ vai

Hoàng Hưng

------------------------------------------------

Trong Gulag, có một đoạn Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn tả, về cái cảm giác giữa những người đã từng ở Gulag, và sau đó, được trả về đời. Họ nhận ra nhau ngay, giữa phố đông người. Chỉ ánh mắt gặp nhau, là biết liền đằng ấy và tớ đã từng ở trong đó.

*

Bài thơ của Hoàng Hưng, như được biết, là một trong 100 bài thơ hay. Không hiểu thi sĩ có tiên tri ra được cái sự bí nhiệm của con số hay không, nhưng có vẻ như ông rất quan tâm đến nó, chỉ để "đếm" thời gian: vợ khóc 'một' đêm. con lạ 'một' ngày. Một năm sau còn nghẹn giữa cuộc vui, hai năm sau còn toát mồ hôi. Năm năm, muời năm... một hôm, một đêm...

Liệu tất cả những cân đo đong đếm đó, là để qui chiếu về câu: Nhất nhật tại tù thiên thu tại ngoại?

Câu này, lại trở thành một ẩn dụ, nếu so cảnh tại ngoại của ông, như được miêu tả trong bài thơ:

Có vẻ như cái cảnh trở về đời kia, vẫn chỉ là, tù trong tù.

Tuy nhiên, khi đọc như thế, có vẻ như hạ thấp bài thơ.

Bài thơ Hoàng Hưng bảnh hơn cách đọc đó nhiều. Có cái vẻ thanh thoát, vượt lên trên tất cả của nhà thơ. Đây cũng là điều nhân loại tìm đọc Gulag của Solz: Cái thái độ đạo đức, nhân bản của tác phẩm và của tác giả.

Giọng kể của Solz là một thứ đạo đức kinh của một linh hồn bị đọa đầy tìm mong sự cứu chuộc, mặc khải, tái sinh, "trẻ mãi không già".

Nó đem đến hy vọng.

Câu thơ "Mười năm còn quen ngồi một mình trong bóng tối" làm nhớ một chi tiết về một nhà thơ trong nhóm Nhân Văn, [không nhớ là ai], ông quen ngồi một mình đến nỗi bóng in lên tường, thành một cái vệt, thời gian không làm sao xóa mờ.

Nếu như thế, một người quen ngồi một mình trong bóng tối, cái bóng của người đó in lên tường mới khủng khiếp làm sao.

Không ai có thể nhìn thấy nó, để mà hỏi thử, thời gian, khi nào thì mới xoá... xong!

Nguyễn Quốc Trụ

Comments

Hoang Hung Cảm

ơn nhà văn Nguyễn Q Trụ và bạn Son LyNgoc. Cái bóng ấy đến 2008 vãn in

lên tường Trung tâm VH Pháp ở HN khi tôi đọc bài thơ Tù, và đc làm bìa

sách cuốn Thơ song ngữ Ác Mộng-Nightmares do Văn Học xuất bản tại Cali

tháng 9/2018

Manage

Note:

Nhân vị bằng hữu FB post lại bài viết, bèn đi thêm 1 đường về bài thơ của HH, song song với bài điểm cuốn Truyện Tù Kolyma [Stories] của Varlam Shalamov, “To Hell and Back” trên tờ NYRB, số Dec 6, 2018, cùng lúc, dịch & giới thiệu New Tinvan & FB, 1 truyện rất ngắn, ở trong đó.

https://www.nybooks.com/…/12/06/varlam-shalamov-hell-and-b…/

https://www.nybooks.com/dai…/2018/…/20/tales-from-the-gulag/

TRAMPLING THE SNOW

How do you trample a road through virgin snow? One man walks ahead, sweating and cursing, barely able to put one foot in front of the other, getting stuck every minute in the deep, porous snow. This man goes a long way ahead, leaving a trail of uneven black holes. He gets tired, lies down in the snow, lights a cigarette, and the tobacco smoke forms a blue cloud over the brilliant white snow. Even when he has moved on, the smoke cloud still hovers over his resting place. The air is almost motionless. Roads are always made on calm days, so that human labor is not swept away by wind. A man makes his own landmarks in this unbounded snowy waste: a rock, a tall tree. He steers his body through the snow like a helmsman steering a boat along a river, from one bend to the next.

The narrow, uncertain footprints he leaves are followed by five or six men walking shoulder to shoulder. They step around the footprints, not in them. When they reach a point agreed on in advance, they turn around and walk back so as to trample down this virgin snow where no human foot has trodden. And so a trail is blazed. People, convoys of sleds, tractors can use it. If they had walked in single file, there would have been a barely passable narrow trail, a path, not a road: a series of holes that would be harder to walk over than virgin snow. The first man has the hardest job, and when he is completely exhausted, another man from this pioneer group of five steps forward. Of all the men following the trailblazer, even the smallest, the weakest must not just follow someone else’s footprints but must walk a stretch of virgin snow himself. As for riding tractors or horses, that is the privilege of the bosses, not the underlings.

1956

CONDENSED MILK

Hunger made our envy as dull and feeble as all our other feelings. We had no strength left for feelings, to search for easier work, to walk, to ask, to beg. We envied only those we knew, with whom we had come into this world, if they had managed to get work in the office, the hospital, or the stables, where there were no long hours of heavy physical work, which was glorified on the arches over all the gates as a matter for valor and heroism. In a word, we envied only Shestakov.

Only something external was capable of taking us out of our indifference, of distracting us from the death that was slowly getting nearer. An external, not an internal force. Internally, everything was burned out, devastated; we didn’t care, and we made plans only as far as the next day.

Now, for instance, I wanted to get away to the barracks, lie down on the bunks, but I was still standing by the doors of the food shop. The only people allowed to buy things in the shop were those convicted of nonpolitical crimes, including recidivist thieves who were classified as “friends of the people.” There was no point in our being there, but we couldn’t take our eyes off the chocolate-colored loaves of bread; the heavy, sweet smell of fresh bread teased our nostrils and even made our heads spin. So I stood there looking at the bread, not knowing when I would find the strength to go back to the barracks. That was when Shestakov called me over.

I had gotten to know Shestakov on the mainland, in Moscow’s Butyrki prison. We were in the same cell. We were acquaintances then, not friends. When we were in the camps, Shestakov did not work at the mine pit face. He was a geological engineer, so he was taken on to work as a prospecting geologist, presumably in the office. The lucky man barely acknowledged his Moscow acquaintances. We didn’t take offense—God knows what orders he might have had on that account. Charity begins at home, etc.

“Have a smoke,” Shestakov said as he offered me a piece of newspaper, tipped some tobacco into it, and lit a match, a real match.

I lit up.

“I need to have a word with you,” said Shestakov.

“With me?”

“Yes.”

We moved behind the barracks and sat on the edge of an old pit face. My legs immediately felt heavy, while Shestakov cheerfully swung his nice new government boots—they had a faint whiff of cod-liver oil. His trousers were rolled up, showing chessboard-patterned socks. I surveyed Shestakov’s legs with genuine delight and even a certain amount of pride. At least one man from our cell was not wearing foot bindings instead of socks. The ground beneath us was shaking from muffled explosions as the earth was being prepared for the night shift. Small pebbles were falling with a rustling sound by our feet; they were as gray and inconspicuous as birds.

“Let’s move a bit farther,” said Shestakov.

“It won’t kill you, no need to be afraid. Your socks won’t be damaged.”

“I’m not thinking about my socks,” said Shestakov, pointing his index finger along the line of the horizon. “What’s your view about all this?”

“We’ll probably die,” I said. That was the last thing I wanted to think about.

“No, I’m not willing to die.”

“Well?”

“I have a map,” Shestakov said in a wan voice. “I’m going to take some workmen—I’ll take you—and we’ll go to Black Springs, fifteen kilometers from here. I’ll have a pass. And we can get to the sea. Are you willing?” He explained this plan in a hurry, showing no emotion.

“And when we reach the sea? Are we sailing somewhere?”

“That doesn’t matter. The important thing is to make a start. I can’t go on living like this. ‘Better to die on one’s feet than live on one’s knees,’” Shestakov pronounced solemnly. “Who said that?”

Very true. The phrase was familiar. But I couldn’t find the strength to recall who said it and when. I’d forgotten everything in books. I didn’t believe in bookish things. I rolled up my trousers and showed him my red sores from scurvy.

“Well, being in the forest will cure that,” said Shestakov, “what with the berries and the vitamins. I’ll get you out, I know the way. I have a map.”

I shut my eyes and thought. There were three ways of getting from here to the sea, and they all involved a journey of five hundred kilometers, at least. I wouldn’t make it, nor would Shestakov. He wasn’t taking me as food for the journey, was he? Of course not. But why was he lying? He knew that just as well as I did. Suddenly I was frightened of Shestakov, the only one of us who’d managed to get a job that matched his qualifications. Who fixed him up here, and what had it cost? Anything like that had to be paid for. With someone else’s blood, someone else’s life.

“I’m willing,” I said, opening my eyes. “Only I’ve got to feed myself up first.”

“That’s fine, fine. I’ll see you get more food. I’ll bring you some . . . tinned food. We’ve got lots. . . .”

There are lots of different tinned foods—meat, fish, fruit, vegetables—but the best of all is milk, condensed milk. Condensed milk doesn’t have to be mixed with boiling water. You eat it with a spoon, or spread it on bread, or swallow it drop by drop from the tin, eating it slowly, watching the bright liquid mass turn yellow with starry little drops of sugar forming on the can. . . .

“Tomorrow,” I said, gasping with joy, “tinned milk.”

“Fine, fine. Milk.” And Shestakov went off.

I returned to the barracks, lay down, and shut my eyes. It was hard to think. Thinking was a physical process. For the first time I saw the full extent of the material nature of our psyche, and I felt its palpability. Thinking hurt. But thinking had to be done. He was going to get us to make a run for it and then hand us in: that much was completely obvious. He would pay for his office job with our blood, my blood. We’d either be killed at Black Springs, or we’d be brought back alive and given a new sentence: another fifteen years or so. He must be aware that getting out of here was impossible. But milk, condensed milk. . . .

I fell asleep and in my spasmodic hungry sleep I dreamed of Shestakov’s can of condensed milk: a monstrous tin can with a sky-blue label. Enormous, blue as the night sky, the can had thousands of holes in it and milk was oozing out and flowing in a broad stream like the Milky Way. And I had no trouble reaching up to the sky to eat the thick, sweet, starry milk.

I don’t remember what I did that day or how I worked. I was waiting and waiting for the sun to sink in the west, for the horses to start neighing, for they were better than people at sensing that the working day was ending.

The siren rang out hoarsely; I went to the barracks where Shestakov lived. He was waiting for me on the porch. The pockets of his quilted jacket were bulging.

We sat at a big, scrubbed table in the barracks, and Shestakov pulled two cans of condensed milk out of a pocket.

I used the corner of an ax to pierce a hole in one can. A thick white stream flowed onto the lid and onto my hand.

“You should have made two holes. To let the air in,” said Shestakov.

“Doesn’t matter,” I said, licking my sweet dirty fingers.

“Give us a spoon,” Shestakov asked, turning to the workmen who were standing around us. Ten shiny, well-licked spoons were stretched over the table. They were all standing to watch me eat. That wasn’t for lack of tact or out of any hidden desire to help themselves. None of them even hoped that I would share this milk with them. That would have been unprecedented; any interest in what someone else was eating was selfless. I also knew that it was impossible not to look at food disappearing into someone else’s mouth. I made myself as comfortable as I could and consumed the milk without bread, just washing it down occasionally with cold water. I finished the two cans. The spectators moved away; the show was over. Shestakov looked at me with sympathy.

“You know what,” I said, carefully licking the spoon. “I’ve changed my mind. You can leave without me.”

Shestakov understood me and walked out without saying a thing.

This was, of course, a petty revenge, as weak as my feelings. But what else could I have done? I couldn’t warn the others: I didn’t know them. But I should have warned them: Shestakov had managed to persuade five others. A week later they ran off; two were killed not far from Black Springs, three were tried a month later. Shestakov’s own case was set aside in the process, and he was soon moved away somewhere. I met him at another mine six months later. He didn’t get an additional sentence for escaping. The authorities had used him but had kept to the rules. Things might have been different.

He was working as a geological prospector, he was clean-shaven and well-fed, and his chess-pattern socks were still intact. He didn’t greet me when he saw me, which was a pity. Two tins of condensed milk was not really worth making a fuss about, after all.

1956

—translated by Donald Rayfield

Note: Gấu mua cả tờ báo – do không cho đọc trọn bài viết – và cuốn truyện, và đọc bài điểm, thì biết được rằng, cái truyện ngắn tuyệt vời nhất, và hợp với chúng ta vào cái mùa Noel tuyết phủ đầy trời này, ở xứ thật lạnh này – cái tủ lạnh như 1 ông bạn thi sĩ Vương Tân viết, trong bài viết về Gấu – là cái truyện post sau đây, và sẽ đi 1 đường tiếng Mít liền, như 1 lời chúc Noel bảnh nhất, với chúng ta!

Cẩn bạch.

Trong bài điểm có 1 nhận xét về sự khác biệt giữa Gulag và Lò Thiêu: Lò Thiêu – Lò Trại Cải Tạo - làm sao có được, nếu thiếu lò đốt củi [oven] của Trọng Lú, và những bậc đàn anh của hắn, và cũng thế Gulag làm có được nếu thiếu… tuyết!

Nhân vị bằng hữu FB post lại bài viết, bèn đi thêm 1 đường về bài thơ của HH, song song với bài điểm cuốn Truyện Tù Kolyma [Stories] của Varlam Shalamov, “To Hell and Back” trên tờ NYRB, số Dec 6, 2018, cùng lúc, dịch & giới thiệu New Tinvan & FB, 1 truyện rất ngắn, ở trong đó.

https://www.nybooks.com/…/12/06/varlam-shalamov-hell-and-b…/

https://www.nybooks.com/dai…/2018/…/20/tales-from-the-gulag/

TRAMPLING THE SNOW

How do you trample a road through virgin snow? One man walks ahead, sweating and cursing, barely able to put one foot in front of the other, getting stuck every minute in the deep, porous snow. This man goes a long way ahead, leaving a trail of uneven black holes. He gets tired, lies down in the snow, lights a cigarette, and the tobacco smoke forms a blue cloud over the brilliant white snow. Even when he has moved on, the smoke cloud still hovers over his resting place. The air is almost motionless. Roads are always made on calm days, so that human labor is not swept away by wind. A man makes his own landmarks in this unbounded snowy waste: a rock, a tall tree. He steers his body through the snow like a helmsman steering a boat along a river, from one bend to the next.

The narrow, uncertain footprints he leaves are followed by five or six men walking shoulder to shoulder. They step around the footprints, not in them. When they reach a point agreed on in advance, they turn around and walk back so as to trample down this virgin snow where no human foot has trodden. And so a trail is blazed. People, convoys of sleds, tractors can use it. If they had walked in single file, there would have been a barely passable narrow trail, a path, not a road: a series of holes that would be harder to walk over than virgin snow. The first man has the hardest job, and when he is completely exhausted, another man from this pioneer group of five steps forward. Of all the men following the trailblazer, even the smallest, the weakest must not just follow someone else’s footprints but must walk a stretch of virgin snow himself. As for riding tractors or horses, that is the privilege of the bosses, not the underlings.

1956

CONDENSED MILK

Hunger made our envy as dull and feeble as all our other feelings. We had no strength left for feelings, to search for easier work, to walk, to ask, to beg. We envied only those we knew, with whom we had come into this world, if they had managed to get work in the office, the hospital, or the stables, where there were no long hours of heavy physical work, which was glorified on the arches over all the gates as a matter for valor and heroism. In a word, we envied only Shestakov.

Only something external was capable of taking us out of our indifference, of distracting us from the death that was slowly getting nearer. An external, not an internal force. Internally, everything was burned out, devastated; we didn’t care, and we made plans only as far as the next day.

Now, for instance, I wanted to get away to the barracks, lie down on the bunks, but I was still standing by the doors of the food shop. The only people allowed to buy things in the shop were those convicted of nonpolitical crimes, including recidivist thieves who were classified as “friends of the people.” There was no point in our being there, but we couldn’t take our eyes off the chocolate-colored loaves of bread; the heavy, sweet smell of fresh bread teased our nostrils and even made our heads spin. So I stood there looking at the bread, not knowing when I would find the strength to go back to the barracks. That was when Shestakov called me over.

I had gotten to know Shestakov on the mainland, in Moscow’s Butyrki prison. We were in the same cell. We were acquaintances then, not friends. When we were in the camps, Shestakov did not work at the mine pit face. He was a geological engineer, so he was taken on to work as a prospecting geologist, presumably in the office. The lucky man barely acknowledged his Moscow acquaintances. We didn’t take offense—God knows what orders he might have had on that account. Charity begins at home, etc.

“Have a smoke,” Shestakov said as he offered me a piece of newspaper, tipped some tobacco into it, and lit a match, a real match.

I lit up.

“I need to have a word with you,” said Shestakov.

“With me?”

“Yes.”

We moved behind the barracks and sat on the edge of an old pit face. My legs immediately felt heavy, while Shestakov cheerfully swung his nice new government boots—they had a faint whiff of cod-liver oil. His trousers were rolled up, showing chessboard-patterned socks. I surveyed Shestakov’s legs with genuine delight and even a certain amount of pride. At least one man from our cell was not wearing foot bindings instead of socks. The ground beneath us was shaking from muffled explosions as the earth was being prepared for the night shift. Small pebbles were falling with a rustling sound by our feet; they were as gray and inconspicuous as birds.

“Let’s move a bit farther,” said Shestakov.

“It won’t kill you, no need to be afraid. Your socks won’t be damaged.”

“I’m not thinking about my socks,” said Shestakov, pointing his index finger along the line of the horizon. “What’s your view about all this?”

“We’ll probably die,” I said. That was the last thing I wanted to think about.

“No, I’m not willing to die.”

“Well?”

“I have a map,” Shestakov said in a wan voice. “I’m going to take some workmen—I’ll take you—and we’ll go to Black Springs, fifteen kilometers from here. I’ll have a pass. And we can get to the sea. Are you willing?” He explained this plan in a hurry, showing no emotion.

“And when we reach the sea? Are we sailing somewhere?”

“That doesn’t matter. The important thing is to make a start. I can’t go on living like this. ‘Better to die on one’s feet than live on one’s knees,’” Shestakov pronounced solemnly. “Who said that?”

Very true. The phrase was familiar. But I couldn’t find the strength to recall who said it and when. I’d forgotten everything in books. I didn’t believe in bookish things. I rolled up my trousers and showed him my red sores from scurvy.

“Well, being in the forest will cure that,” said Shestakov, “what with the berries and the vitamins. I’ll get you out, I know the way. I have a map.”

I shut my eyes and thought. There were three ways of getting from here to the sea, and they all involved a journey of five hundred kilometers, at least. I wouldn’t make it, nor would Shestakov. He wasn’t taking me as food for the journey, was he? Of course not. But why was he lying? He knew that just as well as I did. Suddenly I was frightened of Shestakov, the only one of us who’d managed to get a job that matched his qualifications. Who fixed him up here, and what had it cost? Anything like that had to be paid for. With someone else’s blood, someone else’s life.

“I’m willing,” I said, opening my eyes. “Only I’ve got to feed myself up first.”

“That’s fine, fine. I’ll see you get more food. I’ll bring you some . . . tinned food. We’ve got lots. . . .”

There are lots of different tinned foods—meat, fish, fruit, vegetables—but the best of all is milk, condensed milk. Condensed milk doesn’t have to be mixed with boiling water. You eat it with a spoon, or spread it on bread, or swallow it drop by drop from the tin, eating it slowly, watching the bright liquid mass turn yellow with starry little drops of sugar forming on the can. . . .

“Tomorrow,” I said, gasping with joy, “tinned milk.”

“Fine, fine. Milk.” And Shestakov went off.

I returned to the barracks, lay down, and shut my eyes. It was hard to think. Thinking was a physical process. For the first time I saw the full extent of the material nature of our psyche, and I felt its palpability. Thinking hurt. But thinking had to be done. He was going to get us to make a run for it and then hand us in: that much was completely obvious. He would pay for his office job with our blood, my blood. We’d either be killed at Black Springs, or we’d be brought back alive and given a new sentence: another fifteen years or so. He must be aware that getting out of here was impossible. But milk, condensed milk. . . .

I fell asleep and in my spasmodic hungry sleep I dreamed of Shestakov’s can of condensed milk: a monstrous tin can with a sky-blue label. Enormous, blue as the night sky, the can had thousands of holes in it and milk was oozing out and flowing in a broad stream like the Milky Way. And I had no trouble reaching up to the sky to eat the thick, sweet, starry milk.

I don’t remember what I did that day or how I worked. I was waiting and waiting for the sun to sink in the west, for the horses to start neighing, for they were better than people at sensing that the working day was ending.

The siren rang out hoarsely; I went to the barracks where Shestakov lived. He was waiting for me on the porch. The pockets of his quilted jacket were bulging.

We sat at a big, scrubbed table in the barracks, and Shestakov pulled two cans of condensed milk out of a pocket.

I used the corner of an ax to pierce a hole in one can. A thick white stream flowed onto the lid and onto my hand.

“You should have made two holes. To let the air in,” said Shestakov.

“Doesn’t matter,” I said, licking my sweet dirty fingers.

“Give us a spoon,” Shestakov asked, turning to the workmen who were standing around us. Ten shiny, well-licked spoons were stretched over the table. They were all standing to watch me eat. That wasn’t for lack of tact or out of any hidden desire to help themselves. None of them even hoped that I would share this milk with them. That would have been unprecedented; any interest in what someone else was eating was selfless. I also knew that it was impossible not to look at food disappearing into someone else’s mouth. I made myself as comfortable as I could and consumed the milk without bread, just washing it down occasionally with cold water. I finished the two cans. The spectators moved away; the show was over. Shestakov looked at me with sympathy.

“You know what,” I said, carefully licking the spoon. “I’ve changed my mind. You can leave without me.”

Shestakov understood me and walked out without saying a thing.

This was, of course, a petty revenge, as weak as my feelings. But what else could I have done? I couldn’t warn the others: I didn’t know them. But I should have warned them: Shestakov had managed to persuade five others. A week later they ran off; two were killed not far from Black Springs, three were tried a month later. Shestakov’s own case was set aside in the process, and he was soon moved away somewhere. I met him at another mine six months later. He didn’t get an additional sentence for escaping. The authorities had used him but had kept to the rules. Things might have been different.

He was working as a geological prospector, he was clean-shaven and well-fed, and his chess-pattern socks were still intact. He didn’t greet me when he saw me, which was a pity. Two tins of condensed milk was not really worth making a fuss about, after all.

1956

—translated by Donald Rayfield

Note: Gấu mua cả tờ báo – do không cho đọc trọn bài viết – và cuốn truyện, và đọc bài điểm, thì biết được rằng, cái truyện ngắn tuyệt vời nhất, và hợp với chúng ta vào cái mùa Noel tuyết phủ đầy trời này, ở xứ thật lạnh này – cái tủ lạnh như 1 ông bạn thi sĩ Vương Tân viết, trong bài viết về Gấu – là cái truyện post sau đây, và sẽ đi 1 đường tiếng Mít liền, như 1 lời chúc Noel bảnh nhất, với chúng ta!

Cẩn bạch.

Trong bài điểm có 1 nhận xét về sự khác biệt giữa Gulag và Lò Thiêu: Lò Thiêu – Lò Trại Cải Tạo - làm sao có được, nếu thiếu lò đốt củi [oven] của Trọng Lú, và những bậc đàn anh của hắn, và cũng thế Gulag làm có được nếu thiếu… tuyết!

Comments

Post a Comment