Book Review: Kafka's Last Trial

The world

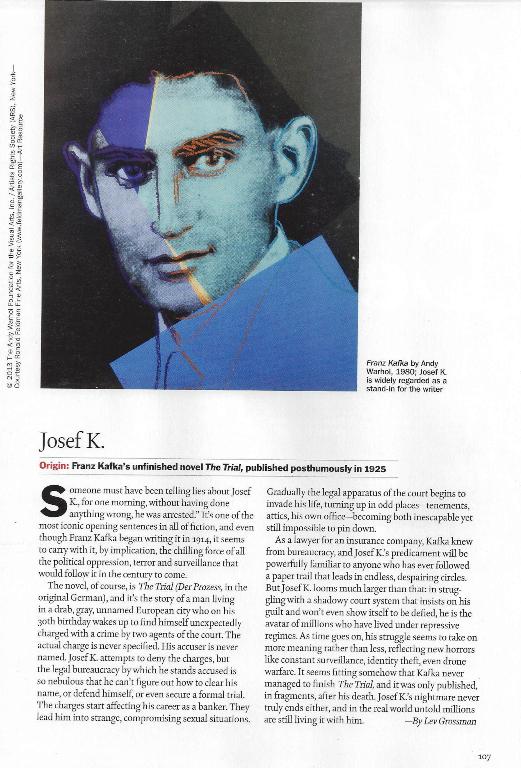

was Kafkaesque before Franz Kafka; all he did was contribute the adjective. All

the same, Kafka remains a special case. As George Steiner pointed out, no other

great writer, not even Shakespeare, managed to arrogate to himself and make uniquely

his own a letter of the alphabet. In the darker realm of literature, at least,

K is king.

The adjective "Kafkaesque" has, of course, become a

cliché. Even Max Brod, his friend and the man we must thank for disregarding

Kafka's specific, written instructions that all his unpublished work should be

destroyed, protested against the "repulsive expression 'Kafkaesque"',

adding that "Kafkaesque is that which Kafka was not!" But neither was

he what Brod claimed him to be, a "saint of our time".

And Theodor Adorno was right to insist that he was not

"a poet of the Judaic homeland". Indeed, one of the themes running

throughout Benjamin Balint's fascinating and forensically scrupulous account of

the history of Kafka's papers is the writer's deeply ambiguous relationship -

if it can even be called that - with Israel, or, as it still was in his time,

Palestine. While Brod, a typical Mitteleuropean man of letters,

"came", according to the journalist and Zionist Robert Weltsch,

"to complete identification with the Jewish people", Kafka maintained

a sceptical attitude on the "Jewish question". "What have I in

common with the Jews?" he asks in his diary, adding with typically

lugubrious humor, "I have hardly anything in common with myself."

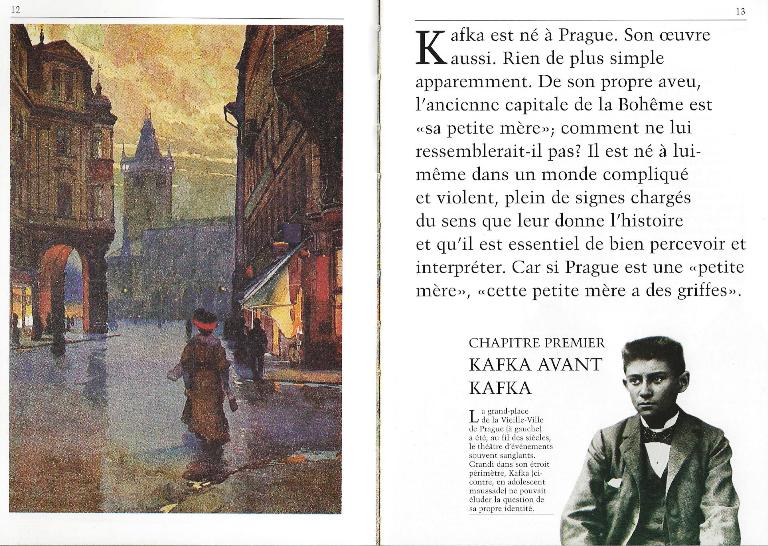

It was not until he discovered what Balint describes as

"an unlikely source of vitality" in the performances of a Yiddish

theatre troupe in Prague's Cafe Savoy that he began to appreciate his Jewish

inheritance. "The cafe was tawdry;' Balint writes, "its doorman a

part-time pimp; yet the burlesque performances had the peculiar effect of

making Kafka's "cheeks tremble".

Kafka filled more than a 100 pages of his diary, Balint tells

us, with accounts of the Yiddish players and their plays. "He was

impressed by their authenticity and 'vigor' (Urwuchsigkeit), and by the ironic idiom itself - in which high and low,

biblical and vernacular rattled against each other.”' Samuel Beckett must have

undergone the same kind of Damascene moment when he first began to look

seriously at the miniature tragicomic epics of Buster Keaton.

Whether his glimpse of a shared Jewish past turned Kafka into

a "Jewish" writer is doubtful. True, he did teach himself Hebrew. Yet

as Kafka himself wrote not long before his death: "What is Hebrew, but

news from far away?" As to Palestine itself, it seems to have been for

Kafka not so much the promised as the improbable land. As he scathingly

remarked: "Many people prowl around Mt Sinai.” Perhaps the matter is best

expressed by the Swiss critic Jean Starobinski: "In the face of Judaism,

Kafka is an exile, albeit one who ceaselessly asks for news of the land he has

left.”

All these aspects of the extremely vexed Jewish question are

pertinent to Balint's subject, which is the battle between Germany and Israel

for possession of Kafka's literary remains, and the plight of the two women caught

in the crossfire - although it must be acknowledged that Esther Hoffe and her

daughter Eva exploded a few bombs themselves.

The Israeli case was stated by Meir Heller, the hard-nosed

lawyer who through eight years of intricate, sometimes bitter, and - yes, alas

- Kafkaesque litigation represented the National Library of Israel: "Like

many other Jews who contributed to western civilization, we think, his legacy

... [and] his manuscripts should be placed here in the Jewish state.”

The other interested party was the German Literature Archive

at Marbach, which, as Balint writes, "wished to add Kafka's manuscripts to

the estates of more than 1,400 writers". The squabble - and it was a

squabble, despite the many high-minded pronouncements that the affair called

forth - centred not on Kafka himself, or his wishes as to the fate of his

papers, but on the ambiguities of the will left behind by Brod, the original

keeper of the archive. A tireless, prolific and for the most part mediocre

writer and journalist, Brod was Kafka's closest friend and confidant, and

regarded him with, as he confessed, "fanatical veneration".

After the second world war, Brod settled in Palestine. Kafka

had entrusted his archive to Brod with instructions to destroy it, instructions

that Brod insisted he assured Kafka he had no intention of carrying out. In Tel

Aviv, Brod became friends with another German exile, Otto Hoffe, and his wife,

Esther. Brod, whose own wife hadnrecently died and whose lover had left him, latched

on to the Hoffes, and took on Esther as his secretary, and perhaps more -

although Esther's daughter Eva insisted that Esther's relation to Brod

"wasn't carnal, it was spiritual".

Whatever the nature of the connection between the two, on his

death in 1968 Brod left Esther in possession of bulk of Kafka's papers, including

original manuscripts of novels and stories, and a wealth of correspondence.

Balint, who is a library fellow at the Van Leer Institute in Jerusalem, emphasizes

that for decades the Israeli state showed no interest in securing the papers,

and did not even react when Esther put some manuscripts up for auction.

In time, Esther

left what remained of them - a substantial haul, despite those auctions - to

Eva, still living in Tel Aviv. At once Israel, in the form of its National

Library, moved to contest Esther's will, provoking the Marbach Literature

Archive to weigh in with its own case. Since it had already been in negotiation

with Esther to buy Brod's estate, including the Kafka papers, the archive's

director held that it had the right at least to make a bid against the Israeli

claim. There followed no fewer than three trials in Israel, which ended with

the supreme court's decision that Eva must hand over, without recompense, the

entire Brod papers, including Kafka's legacy, to the library.

Who was in the right, or could there even be a

"right" decision in such a case, involving the claims of the Jewish

state against a nation that had permitted the murder of6 million Jews? The real

loser was not the Marbach archive but Eva, who died in August 2018. Balint, in

a passage that Kafka would surely have admired, sums up the matter eloquently

and movingly when he writes: "Like the man from the country in Kafka's

parable 'Before the Law', Eva Hoffe remained stranded and confounded outside

the door of the law ... Her inheritance was the trial itself. Paradoxically, she

had inherited her disinheritance, inherited the impossibility of carrying out

her mother's will. She possessed only her dispossession:'

JOHN

BANVILLE IS AN IRISH NOVELIST AND SCREENWRITER

https://literaryreview.co.uk/brods-bequest

https://literaryreview.co.uk/brods-bequest

In his lifetime, Franz Kafka was not exactly a runaway success. His first book, Meditation, a collection of eighteen prose poems, was published in an edition of eight hundred copies and soon vanished. His second book, A Country Doctor,

was mentioned by only one reviewer; Kafka’s father did not deign even

to open it. Most of his slender output was coaxed into print by his good

friend Max Brod, who saw genius in this strange man and was baffled and

appalled by his chronic self-condemnation. When Kafka died in 1924,

Brod was given a plain and uncompromising order. ‘Dearest Max,’ Franz

wrote, ‘My last request: Everything I leave behind me … in the way of

notebooks, manuscripts, letters, my own and other people’s, sketches and

so on, is to be burned unread and to the last page.’

Obviously, Brod disobeyed, and most people have thought he chose the noble option. Without this ‘betrayal’, we would have no The Trial, no The Castle, no ‘Metamorphosis’, none of Kafka’s fascinating and harrowing letters to his girlfriends, none of his Diaries,

and no one would be using or misusing the adjective ‘Kafkaesque’. In

short, our conception of what has most mattered in 20th-century

literature would be different. W H Auden, not at first sight the most

likely of fans, suggested in 1941 that ‘had one to name the artist who

comes nearest to bearing the same kind of relation to our age that

Dante, Goethe and Shakespeare bore to theirs, Kafka is the first one

would think of.’

This is about the largest claim one could

make for any writer, since the trio Auden elsewhere referred to as

‘Daunty, Gouty, and Shopkeeper’, borrowing from Joyce, are often thought

of as the great universal geniuses: the writers who belong not only to

their respective national literatures but to (Goethe first floated this

idea) World Literature. Plenty of people have agreed with Auden that

Kafka belongs to all literate humanity, but quite a few have dissented,

sometimes vehemently. Some of the dissenters have been lawyers.

The question of who owns Kafka is at the heart of Benjamin Balint’s thought-provoking and assiduously researched Kafka’s Last Trial,

which (to simplify) is about the attempt by the state of Israel to

prevent the sale of Kafka’s manuscripts from a private collection there

to anywhere overseas, particularly to the German Literature Archive in

Marbach. Spoiler alert for those who were not reading the newspapers in

2016: the state won. But Balint’s book is not so much about the outcome

as it is about the arguments that were brought forward.

The reason Kafka’s papers ended up in

Israel is simple: Brod, a Zionist, brought them there. After Brod’s

death, in 1968, the archive passed to his secretary and confidante

Esther Hoffe. She died in 2007 at the age of 101, leaving the papers to

her daughters Eva and Ruth; Ruth died not long afterwards, leaving Eva

Hoffe as the owner of the cache, which was of considerable size. In the

mid-1980s, Esther Hoffe commissioned a Swiss philologist to make an

inventory of the manuscripts, some of which she kept in her house on

Spinoza Street, while others were deposited in banks in Zurich and Tel

Aviv. The philologist found that the collection ran to about twenty

thousand pages.

There are good reasons to sympathise with

the Israeli case, and one of them is all too obvious. As Professor Otto

Dov Kulka said to the New York Times, ‘They say the

papers will be safer in Germany. The Germans will take very good care of

them … Well, the Germans don’t have a very good history of taking care

of Kafka’s things. They didn’t take good care of his sisters.’

Lest we forget, each of Kafka’s three sisters was murdered by the Nazis. Elli and Valli were deported to the Łódź

ghetto in 1941 and sent to the gas chambers of Chełmno in September

1942. Ottla, the youngest and by all accounts the most vivacious of the

girls, was killed in Auschwitz in October 1943. Kafka’s lover, Milena

Jesenská, died in Ravensbrück concentration camp, his second fiancée,

Julie Wohryzek, in Auschwitz, and his friend Yitzhak Lowy in Treblinka.

Kafka’s favourite uncle, Siegfried, took his own life on the eve of his

deportation to Theresienstadt. At least five of Kafka’s classmates were

also murdered in concentration camps. It seems all but certain that, had

Kafka lived on into his fifties, he too would have perished in a camp.

Even without taking all that into

account, the state of Israel had good cause for concern. Some of the

country’s finest spirits felt that Kafka was central to its identity.

The great Kabbalah scholar Gershom Scholem, for instance, once said that

for him, there were only three canonical Jewish texts: the Hebrew

Bible, the Zohar and the collected works of Kafka. Moreover, Esther had

not been as scrupulous a custodian as the state might have wished: she

had often sold manuscripts abroad, including that of The Trial, which went for £1 million at Sotheby’s in 1988.

But the Israeli case was far from

waterproof. For one thing, Israel had been very slow to accept Kafka as

an important writer. In the early years, as Balint shrewdly points out,

‘Kafka’s motifs – humiliation and powerlessness, anomie and alienation,

debilitating guilt and self-condemnation – were the very preoccupations

Israel’s founding generations sought to overcome.’ Young Israel wanted

farmers, engineers and architects, not neurasthenic idlers. Even though

his reputation has picked up in more recent years, he remains less

significant in Israel than in, say, Germany, France or America. As

Reiner Stach, author of a monumental Kafka biography, put it, ‘To speak

here of Israeli cultural assets seems to me absurd. In Israel, there is

neither a complete edition of Kafka’s works, nor a single street named

after him.’

There are no obvious villains or heroes

in this tale, though it is hard not to think that there was a victim:

Eva Hoffe, who said that she felt ‘raped’ by the court verdict, shaved

her head in mute protest and, according to her friends, came close to

suicide. It does seem unjust that she was not compensated for the loss

of her inheritance with so much as a shekel. To describe her

entanglements with the law as Kafkaesque is, for once, reasonable

enough. Kafka, who always sided with the weak, the poor, the outcast,

the wounded and the sick, would surely have regarded her with

compassion. As so often, he deserves the last word: ‘What have I in

common with the Jews? I have hardly anything in common with myself.’

A Crossbreed

I have a

curious animal, half-cat, half-lamb. It is a legacy from my father. But

it only

developed in my time; formerly it was far more lamb than cat. Now it is

both in

about equal parts. From the cat it takes its head and claws, from the

lamb its

size and shape; from both its eyes, which are wild and changing, its

hair,

which is soft, lying close to its body, its movements, which partake

both of

skipping and slinking. Lying on the window-sill in the sun it curls

itself up

in a ball and purrs; out in the meadow it rushes about as if mad and is

scarcely to be caught. It flies from cats and makes to attack lambs. On

moonlight nights its favorite promenade is the tiles. It cannot mew and

it loathes

rats. Beside the hen-coop it can lie for hours in ambush, but it has

never yet

seized an opportunity for murder.

I feed it on milk; that seems to suit it

best. In long draughts it sucks the milk into it through its teeth of a

beast

of prey. Naturally it is a great source of entertainment for children.

Sunday

morning is the visiting hour. I sit with the little beast on my knees,

and the

children of the whole neighborhood stand round me. Then the strangest

questions

are asked, which no human being could answer: Why there is only one

such

animal, why I rather than anybody else should own it, whether there was

ever an

animal like it before and what would happen if it died, whether it

feels

lonely, why it has no children, what it is called, etc.

I never trouble to answer, but confine

myself without further explanation to exhibiting my possession.

Sometimes the

children bring cats with them; once they actually brought two lambs.

But

against all their hopes there was no scene of recognition. The animals

gazed

calmly at each other with their animal eyes, and obviously accepted

their

reciprocal existence as a divine fact.

Sitting on my knees the beast knows neither

fear nor lust of pursuit. Pressed against me it is happiest. It remains

faithful to the family that brought it up. In that there is certainly

no

extraordinary mark of fidelity, but merely the true instinct of an

animal

which, though it has countless step-relations in the world, has perhaps

not a

single blood relation, and to which consequently the protection it has

found

with us is sacred.

Sometimes I cannot help laughing when it

sniffs round me and winds itself between my legs and simply will not be

parted

from me. Not content with being lamb and cat, it almost insists on

being a dog

as well. Once when, as may happen to anyone, I could see no way out of

my

business difficulties and all that depends on such things, and had

resolved to

let everything go, and in this mood was lying in my rocking-chair in my

room,

the beast on my knees, I happened to glance down and saw tears dropping

from

its huge whiskers. Were they mine, or were they the animal's? Had this

cat,

along with the soul of a lamb, the ambitions of a human being? I did

not

inherit much from my father, but this legacy is worth looking at.

It has the restlessness of both beasts,

that of the cat and that of the lamb, diverse as they are. For that

reason its

skin feels too narrow for it. Sometimes it jumps up on the armchair

beside me,

plants its front legs on my shoulder, and puts its muzzle to my ear. It

is as

if it were saying something to me, and as a matter of fact it turns its

head

afterwards and gazes in my face to see the impression its communication

has

made. And to oblige it I behave as if I had understood and nod. Then it

jumps

to the floor and dances about with joy.

Perhaps the knife of the butcher would be a

release for this animal; but as it is a legacy I must deny it that. So

it must

wait until the breath voluntarily leaves its body, even though it

sometimes

gazes at me with a look of human understanding, challenging me to do

the thing

of which both of us are thinking.

FRANZ KAFKA: Description

of a Struggle (Translated from the

German by Tania and James Stern)

Jorge Luis

Borges: The Book of Imaginary Beings

I have a

curious animal, half-cat, half-lamb. It is a legacy from my father: Tôi

có 1

con vật kỳ kỳ, nửa mèo, nửa cừu. Nó là gia tài để lại của ông già của

tôi

Không phải

ngẫu nhiên mà Gregor Samsa thức giấc như là một con bọ ở trong nhà bố

mẹ, mà

không ở một nơi nào khác, và cái con vật khác thường nửa mèo nửa cừu

đó, là thừa

hưởng từ người cha.

Walter Benjamin

Walter Benjamin

Perhaps the

knife of the butcher would be a release for this animal; but as it is a

legacy

I must deny it that. So it must wait until the breath voluntarily

leaves its

body, even though it sometimes gazes at me with a look of human

understanding,

challenging me to do the thing of which both of us are thinking.

Có lẽ con dao của tên đồ tể là 1 giải thoát cho con vật, nhưng tớ đếch chịu như thế, đối với gia tài của bố tớ để lại cho tớ. Vậy là phải đợi cho đến khi hơi thở cuối cùng hắt ra từ con vật khốn khổ khốn nạn, mặc dù đôi lúc, con vật nhìn tớ với cái nhìn thông cảm của 1 con người, ra ý thách tớ, mi làm cái việc đó đi, cái việc mà cả hai đều đang nghĩ tới đó!

Có lẽ con dao của tên đồ tể là 1 giải thoát cho con vật, nhưng tớ đếch chịu như thế, đối với gia tài của bố tớ để lại cho tớ. Vậy là phải đợi cho đến khi hơi thở cuối cùng hắt ra từ con vật khốn khổ khốn nạn, mặc dù đôi lúc, con vật nhìn tớ với cái nhìn thông cảm của 1 con người, ra ý thách tớ, mi làm cái việc đó đi, cái việc mà cả hai đều đang nghĩ tới đó!

“Kafka: Những

năm đốn ngộ” là tập nhì, của cuốn tiểu sử hách xì xằng, masterful, về

Kafka của

Reiner Stach. Tập đầu là về những năm từ

1910 tới 1915, khi Kafka còn trẻ, viết như khùng, như điên, writing

furiously,

vào ban đêm, into the night, trong khi cày 50 giờ/tuần. Tập nhì ghi lại

thời kỳ danh vọng trồi

lên, cho tới khi ông mất, ở một viện an dưỡng ở Áo vào tuổi bốn mươi,

sau những

năm tháng đau khổ vì bịnh lao phổi. (Tập thứ ba, ghi lại những năm đầu

đời, đang

tiến hành).

Trong những năm sau cùng, từ 1916 tới 1924, Kafka nhận được thư, từ giám đốc, quản lý nhà băng, chọc quê ông, khi yêu cầu giải thích những truyện ngắn do ông viết ra (“Thưa Ngài, Ngài làm tôi đếch làm sao vui được. Tôi mua cuốn “Hóa Thân” của Ngài làm quà tặng cho 1 người bà con, nhưng người đó đếch biết làm sao xoay sở, hay là làm gì, với cuốn truyện”).

Trong những năm sau cùng, từ 1916 tới 1924, Kafka nhận được thư, từ giám đốc, quản lý nhà băng, chọc quê ông, khi yêu cầu giải thích những truyện ngắn do ông viết ra (“Thưa Ngài, Ngài làm tôi đếch làm sao vui được. Tôi mua cuốn “Hóa Thân” của Ngài làm quà tặng cho 1 người bà con, nhưng người đó đếch biết làm sao xoay sở, hay là làm gì, với cuốn truyện”).

Đa số đều

cho rằng, ba nhà văn đại diện cho thế kỷ 20 là James Joyce, Marcel

Proust, và Franz Kafka.

Trong ba nhà văn này, người viết xin được chọn Kafka là nhà văn của thế kỷ 20.

Thế kỷ 20 như chúng ta biết, là thế kỷ của hung bạo. Những biểu tượng của nó, là Hitler với Lò Thiêu Người, và Stalin với trại tập trung cải tạo. Điều lạ lùng ở đây là: Kafka mất năm 1924, Hitler nắm quyền vào năm 1933; với Stalin, ngôi sao của ông Thần Đỏ này chỉ sáng rực lên sau Cuộc Chiến Lớn II (1945), và thời kỳ Chiến Tranh Lạnh. Bằng cách nào Kafka nhìn thấy trước hai bóng đen khủng khiếp, là chủ nghĩa Nazi, và chủ nghĩa toàn trị?

Gần hai chục năm sau khi ông mất, nhà thơ người Anh Auden có thể viết, không cố tình nói ngược ngạo, hay tạo sốc: "Nếu phải nêu một tác giả của thời đại chúng ta, sánh được với Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe, và thời đại của họ, Kafka sẽ là người đầu tiên mà người ta nghĩ tới."

G. Steiner cho rằng: "(ngoài Kafka ra) không có thể có tiếng nói chứng nhân nào thật hơn, về bóng đen của thời đại chúng ta." Khi Kafka mất, chỉ có vài truyện ngắn, mẩu văn được xuất bản. Những tác phẩm quan trọng của ông đều được xuất bản sau khi ông mất, do người bạn thân đã không theo di chúc yêu cầu huỷ bỏ. Tại sao thế giới-ác mộng riêng tư của một nhà văn lại trở thành biểu tượng của cả một thế kỷ?

Nhà phê bình

Mác-xít G. Lukacs cho rằng, trong

những phát kiến (inventions) của Kafka, có những dấu vết đặc thù,

của phê

bình xã hội. Viễn ảnh của ông về một hy vọng triệt để, thật u tối: đằng

sau bước

quân hành của cuộc cách mạng vô sản, ông nhìn thấy lợi lộc của nó là

thuộc về bạo

chúa, hay kẻ mị dân. Cuốn tiểu thuyết "Vụ Án" là một huyền thoại quỉ

ma, về tệ nạn hành chánh mà "Căn Nhà U Tối" của Dickens đã tiên đoán.

Kafka là người thừa kế nhà văn người Anh Dickens, không chỉ tài bóp méo

các biểu

tượng định chế (bộ máy kỹ nghệ như là sức mạnh của cái ác, mang tính

huỷ diệt),

ông còn thừa hưởng luôn cơn giận dữ của Dickens, trước cảnh tượng người

bóc lột

người.Trong ba nhà văn này, người viết xin được chọn Kafka là nhà văn của thế kỷ 20.

Thế kỷ 20 như chúng ta biết, là thế kỷ của hung bạo. Những biểu tượng của nó, là Hitler với Lò Thiêu Người, và Stalin với trại tập trung cải tạo. Điều lạ lùng ở đây là: Kafka mất năm 1924, Hitler nắm quyền vào năm 1933; với Stalin, ngôi sao của ông Thần Đỏ này chỉ sáng rực lên sau Cuộc Chiến Lớn II (1945), và thời kỳ Chiến Tranh Lạnh. Bằng cách nào Kafka nhìn thấy trước hai bóng đen khủng khiếp, là chủ nghĩa Nazi, và chủ nghĩa toàn trị?

Gần hai chục năm sau khi ông mất, nhà thơ người Anh Auden có thể viết, không cố tình nói ngược ngạo, hay tạo sốc: "Nếu phải nêu một tác giả của thời đại chúng ta, sánh được với Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe, và thời đại của họ, Kafka sẽ là người đầu tiên mà người ta nghĩ tới."

G. Steiner cho rằng: "(ngoài Kafka ra) không có thể có tiếng nói chứng nhân nào thật hơn, về bóng đen của thời đại chúng ta." Khi Kafka mất, chỉ có vài truyện ngắn, mẩu văn được xuất bản. Những tác phẩm quan trọng của ông đều được xuất bản sau khi ông mất, do người bạn thân đã không theo di chúc yêu cầu huỷ bỏ. Tại sao thế giới-ác mộng riêng tư của một nhà văn lại trở thành biểu tượng của cả một thế kỷ?

Chọn Kafka là tiếng nói chứng nhân đích thực, nhà văn của thế kỷ hung bạo, là chỉ có "một nửa vấn đề". Kafka, theo tôi, còn là người mở ra thiên niên kỷ mới, qua ẩn dụ "người đàn bà ngoại tình".

Thế nào là "người đàn bà ngoại tình"? Người viết xin đưa ra một vài thí dụ: một người ở nước ngoài, nói tiếng nước ngoài, nhưng không thể nào quên được tiếng mẹ đẻ. Một người di dân phải viết văn bằng tiếng Anh, nhưng đề tài hoàn toàn là "quốc tịch gốc, quê hương gốc" của mình. Một người đàn bà lấy chồng ngoại quốc, nhưng vẫn không thể quên tiếng Việt, quê hương Việt. Một người Ả Rập muốn "giao lưu văn hóa" với người Do Thái...

Văn chương Việt hải ngoại, hiện cũng đang ở trong cái nhìn "tiên tri" của Kafka: đâu là quê nhà, đâu là lưu đầy? Đi /Về: cùng một nghĩa như nhau?

Jennifer Tran

Kafka: Years of insight

Những năm đốn ngộ

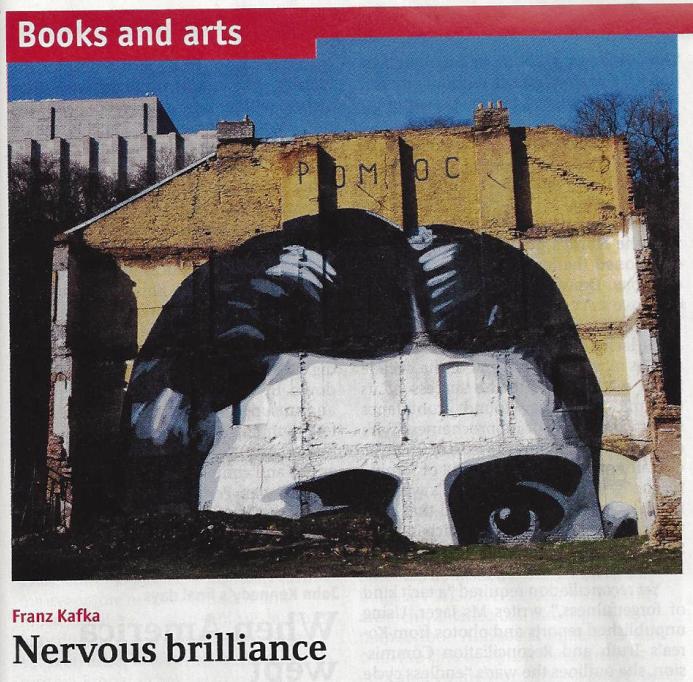

Hình trên

báo giấy còn thấy được 1 con mắt của Kafka.

Note: Nervous brilliance,

tạm dịch, “sáng chói bồn chồn”.

Bỗng nhớ Cô Tư, “sáng chói, đen, và hơi khùng” [thực ra là, “đen, buồn và hơi khùng”]

Bỗng nhớ Cô Tư, “sáng chói, đen, và hơi khùng” [thực ra là, “đen, buồn và hơi khùng”]

Nhưng cuốn

tiểu sử của Mr Stach cũng cho thấy cái phần nhẹ nhàng, sáng sủa hơn của

Kafka. Trong

1 lần holyday, đi chơi với bồ, ông cảm thấy mình bịnh, vì cười nhiều

quá. Trong

những năm sau cùng của đời mình, ông gặp 1 cô gái ngồi khóc ở 1 công

viên, và cô

nàng nói với ông, là cô làm mất con búp bế. Thế là mỗi ngày ông viết

cho cô bé

1 lá thư, trong ba tuần lễ, lèm bèm về con búp bế bị mất. Với người

tình sau cùng,

Dora Diamant, rõ là ông tính lấy làm vợ. Cô này còn dụ ông trở lại được

với Do

Thái giáo.

Những giai thoại trên chọc thủng hình ảnh 1 Kafka khắc khổ, qua tác phẩm của ông. Mr Stach còn vứt vô thùng rác [undermine] những cái nhìn có tính ước lệ [conventional views] về 1 Kakka như 1 nhà tiên tri của những tội ác kinh hoàng ghê rợn [atrocities] sẽ tới (ba chị/em của ông chết trong trại tập trung Nazi, cũng như hai bạn gái của ông). Trong những nhận xét về mục tiêu bài Do Thái, ông mô tả 1 thế giới như ông nhìn thấy nó, đầy nỗi cô đơn và những cá nhân con người bị bách hại, nhưng không phải 1 thế giới không có hy vọng.

Những giai thoại trên chọc thủng hình ảnh 1 Kafka khắc khổ, qua tác phẩm của ông. Mr Stach còn vứt vô thùng rác [undermine] những cái nhìn có tính ước lệ [conventional views] về 1 Kakka như 1 nhà tiên tri của những tội ác kinh hoàng ghê rợn [atrocities] sẽ tới (ba chị/em của ông chết trong trại tập trung Nazi, cũng như hai bạn gái của ông). Trong những nhận xét về mục tiêu bài Do Thái, ông mô tả 1 thế giới như ông nhìn thấy nó, đầy nỗi cô đơn và những cá nhân con người bị bách hại, nhưng không phải 1 thế giới không có hy vọng.

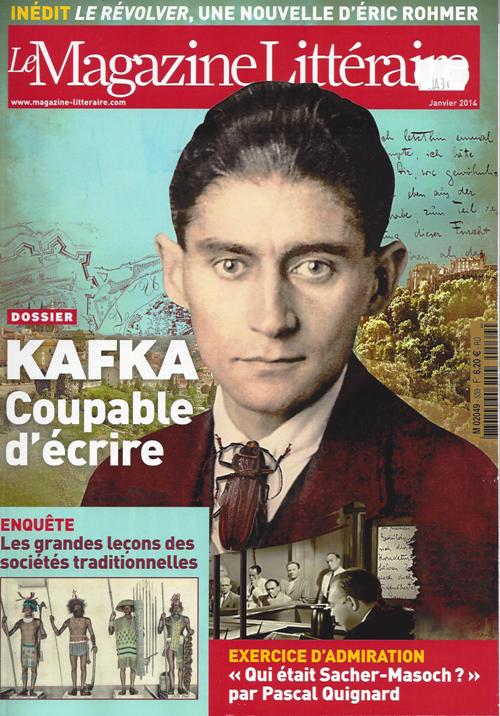

*

Franz

Kafka:

Sáng chói bồn chồn

A definitive biography of a rare writer

Một tiểu sử chung quyết của 1 nhà văn hiếm, lạ.

A definitive biography of a rare writer

Một tiểu sử chung quyết của 1 nhà văn hiếm, lạ.

Kafka: The

Years of Insight. By Reiner Stach. Princeton University Press;

682 pages; $35

and £24.95.

Vào năm

1915, một truyện ngắn được gọi là “Hóa Thân” được xuất bản ở 1 tạp chí

“bèo”

[small] của Đức. Nó kể câu chuyện một anh chàng bán hàng, một buổi sáng

thức

dậy thấy mình biến thành 1 con bọ khổng lồ. Tác giả, một nhân viên dân

sự trung lưu, làm việc tại Prague. Chưa tới 10 năm sau đó, ông mất, một

tác giả

ít được biết tới của ba cuốn tiểu thuyết và vài tác phẩm ngắn hơn.

Nhưng Hóa Thân

– có lẽ chỉ chừng 50 trang - sẽ hóa thân thành 1 con bọ khổng lồ, ấy

chết xin lỗi

- sẽ trở thành nguồn cảm hứng cho hằng hà tác phẩm - những chuyển thể

sân khấu, dàn

dựng kịch nghệ không làm sao đếm nổi, những luận án tiến sĩ thạc sĩ, và

hằng

hà những nhà văn tiếp theo. Hoá Thân,

và cùng với truyện ngắn đó, hai cuốn tiểu

thuyết, Vụ Án, và Tòa Lâu Đài,

đã đóng cứng vị trí của Kafka, như là một trong những nhà văn quan

trọng nhất của

thế kỷ 20.

Hình trên

báo giấy còn thấy được 1 con mắt của Kafka.

Note: Nervous brilliance,

tạm dịch, “sáng chói bồn chồn”.

Bỗng nhớ Cô Tư, “sáng chói, đen, và hơi khùng” [thực ra là, “đen, buồn và hơi khùng”]

Nhưng

cuốn

tiểu sử của Mr Stach cũng cho thấy cái phần nhẹ nhàng, sáng sủa hơn của

Kafka. Trong

1 lần holyday, đi chơi với bồ, ông cảm thấy mình bịnh, vì cười nhiều

quá. Trong

những năm sau cùng của đời mình, ông gặp 1 cô gái ngồi khóc ở 1 công

viên, và cô

nàng nói với ông, là cô làm mất con búp bế. Thế là mỗi ngày ông viết

cho cô bé

1 lá thư, trong ba tuần lễ, lèm bèm về con búp bế bị mất. Với người

tình sau cùng,

Dora Diamant, rõ là ông tính lấy làm vợ. Cô này còn dụ ông trở lại được

với Do

Thái giáo.Bỗng nhớ Cô Tư, “sáng chói, đen, và hơi khùng” [thực ra là, “đen, buồn và hơi khùng”]

Những giai thoại trên chọc thủng hình ảnh 1 Kafka khắc khổ, qua tác phẩm của ông. Mr Stach còn vứt vô thùng rác [undermine] những cái nhìn có tính ước lệ [conventional views] về 1 Kakka như 1 nhà tiên tri của những tội ác kinh hoàng ghê rợn [atrocities] sẽ tới (ba chị/em của ông chết trong trại tập trung Nazi, cũng như hai bạn gái của ông). Trong những nhận xét về mục tiêu bài Do Thái, ông mô tả 1 thế giới như ông nhìn thấy nó, đầy nỗi cô đơn và những cá nhân con người bị bách hại, nhưng không phải 1 thế giới không có hy vọng.

Franz Kafka

Nervous brilliance

A definitive biography of a rare writer

IN 1915 a short story called “The Metamorphosis” (“Die Verwandlung”) was published in a small German magazine. It told the story of Gregor Samsa, a salesman who wakes up one morning to find that he has turned into an enormous bug. The author, Franz Kafka, was a middle-ranking civil servant working in Prague. He would die less than ten years later, a little-known author of three novels and several shorter works. But “The Metamorphosis”—perhaps 50 pages long—would go on to inspire countless stage adaptations and doctoral theses and scores of subsequent writers. The story, along with the novels “The Trial” and “The Castle”, ensured Kafka’s place as one of the most important writers of the 20th century.

In

this section

“Kafka: The Years of Insight” is the second volume of

Reiner Stach’s masterful biography of the author. The first dealt with

the years 1910 to 1915, when Kafka was a young man writing furiously

into the night while working 50-hour weeks. The second volume records

his burgeoning fame up until his death in an Austrian sanatorium at the

age of 40, after years of suffering from tuberculosis. (A third volume,

tracing his early years, is in the works.)In these final years, from 1916 to 1924, Kafka receives letters from quizzical bank managers asking him to explain his stories (“Sir, You have made me unhappy. I bought your ‘Metamorphosis’ as a present for my cousin, but she doesn’t know what to make of the story”). He spends hours nagging away at his prose, only to rip it up, throw it away and start again. He apparently denies being the author of certain stories when asked by other invalids at a retreat. He has four love affairs, mostly through letters, and spends much of his time away from his cramped office at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute. These are years of insight, but also of depression and illness.

Despite the gloom, this biography makes for an excellent read. Mr Stach, a German academic, expertly presents Kafka’s struggles with his work and health against the wider background of the first world war, the birth of Czechoslovakia and the hyperinflation of the 1920s. Alert to the limits of biography, Mr Stach bases everything on archival materials and, where possible, Kafka’s own view of events. He is also wryly aware of the academic cottage industry that has sprung up around Kafka’s work, hints of which had already emerged in his lifetime. “You are so pure, new, independent...that one ought to treat you as if you were already dead and immortal,” wrote one fan.

The picture that emerges is of a difficult, brilliant man. In Mr Stach’s view, Kafka was “a neurotic, hypochondriac, fastidious individual who was complex and sensitive in every regard, who always circled around himself and who made a problem out of absolutely everything”. A decision to visit a married woman, soon to be his lover, takes him three weeks and 20 letters. When writing to his first fiancée, he refers to himself in the third person and struggles to evoke intimacy. Kafka makes decisions only to swiftly unmake them. Other people irritate him. “Sometimes it almost seems to me that life itself is what gets on my nerves,” he wrote to a friend.

But Mr Stach’s biography also shows Kafka’s lighter side. On holiday with a mistress, he feels almost sick with laughter. In the last years of his life he meets a crying young girl in a park who explains that she has lost her doll. He then proceeds to write her a letter a day for three weeks from the perspective of the doll, recounting its exploits. With his final mistress, Dora Diamant, Kafka has no doubt that he wants to marry her. She even inspires him to recover his interest in Judaism.

Such anecdotes pierce the austere image left by Kafka’s work. Mr Stach also effectively undermines conventional views of Kafka as a prophet of the atrocities to come (his three sisters died in Nazi concentration camps, as did two of his mistresses). A frequent target of anti-Semitic remarks, Kafka depicted the world as he saw it, full of lonely and persecuted individuals, but not one without hope.

JANUARY

15, 2014

ON

TRANSLATING KAFKA’S “THE METAMORPHOSIS”

POSTED

BY SUSAN BERNOFSKY

This

essay is adapted from the afterword to the

author’s new translation of “The Metamorphosis,” by Franz Kafka.

Cú

khó sau chót, về dịch, là cái từ trong cái tít. Không

giống từ tiếng Anh, “metamorphosis,”

“hóa

thân”, từ tiếng Đức

Verwandlung

không đề nghị cách hiểu tự nhiên, tằm

nhả tơ xong, chui vô kén, biến thành nhộng, nhộng biến thành

bướm, trong vương quốc loài vật. Thay vì

vậy, đây là 1 từ, từ chuyện thần tiên, dùng để tả sự chuyển hóa, thí dụ

như

trong chuyện cổ tích về 1 cô gái đành phải giả câm để cứu mấy người

anh bị bà phù thuỷ biến thành vịt, mà Simone Weil đã từng đi 1 đường

chú giải

tuyệt vời.

“Hóa thân” là phải hiểu theo nghĩa đó, giống như GCC, có thể đếch chết, và thay vì chết, thì biến thành rồng, như lời chúc SN của bạn DV!

“Hóa thân” là phải hiểu theo nghĩa đó, giống như GCC, có thể đếch chết, và thay vì chết, thì biến thành rồng, như lời chúc SN của bạn DV!

Hà,

hà!

One

last translation problem in the story is the

title itself. Unlike the English “metamorphosis,” the German word Verwandlung

does not suggest a natural change of state associated

with the animal

kingdom such as the change from caterpillar to butterfly. Instead it is

a word

from fairy tales used to describe the transformation, say, of a girl’s

seven

brothers into swans. But the word “metamorphosis” refers to this, too;

its

first definition in the Oxford English Dictionary is “The action or

process of

changing in form, shape, or substance; esp. transformation by

supernatural

means.” This is the sense in which it’s used, for instance, in

translations of

Ovid. As a title for this rich, complex story, it strikes me as the

most

luminous, suggestive choice.

Comments

Post a Comment