Một trang Tin Văn cũ

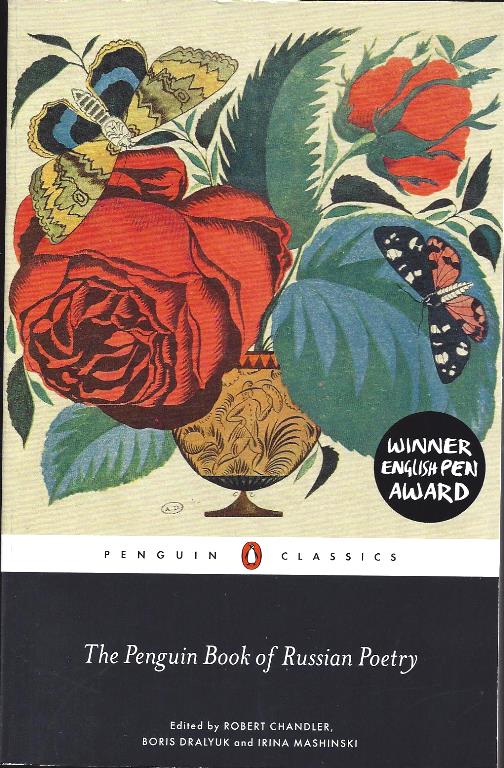

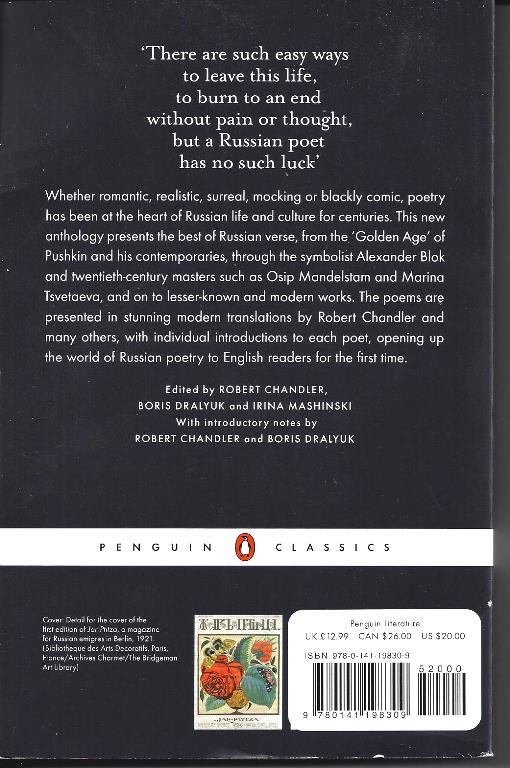

Penguin

Russian

Poetry

http://www.tanvien.net/new_daily_poetry/strong_wods_A_A.html

Valery

Bryusov (1873-1924)

The grandson of a former serf, Valery Yakovlevich Bryusov was born in Moscow. From his schooldays he read widely; as a young man he was determined to make his mark on the literary world. In a diary entry from 1893 he wrote, 'Whether Decadence is false or ridiculous, it is moving forward, developing, and the future will belong to it when it finds a worthy leader. And that leader will be me! Yes, me!"

From 1894 to 1895 Bryusov published three collections of poems entitled Russian Symbolists: An Anthology; most of the poems were his own, but he used a number of pseudonyms to make this new 'Decadent' or 'Symbolist' movement seem more impressive. These anthologies also included Bryusov's translations of such poets as Poe, Mallarrne, Verlaine, Oscar Wilde and Emile Verhaeren.

Bryusov was influential not only as the founder, with Konstantin Balmont, of Russian Symbolism but also as an editor. From 1904 he ran the Skorpion publishing house, and from 1904 until 1909 he also edited the influential journal The Scales. In 1908 he published a historical novel, The Fiery Angel, which Prokofiev later used for an opera libretto. Bryusov's capacity for work was extraordinary. In 1915 he was asked to compile a large anthology of Russian translations of Armenian poetry: he learned the language, read a great deal of background literature and completed most of the translations in less than a year.

In late 1917, when many of his literary colleagues were emigrating, Bryusov declared his support for the Soviet government. In 1920 he joined the Communist Party. There are several accounts of his abusing his position in the Soviet cultural apparatus to attack more gifted colleagues - Khodasevich and Mandelstam among them - of whom he felt envious.

Bryusov is a dull poet. We include the following poem because it has been so well translated by Padraic Breslin, who deserves to be remembered.

*

What if we suffered from the lash

of black defeat and cold and hunger?

Above the world new symbols flash,

the sickle and the workers' hammer.

The soil again our toil will tend,

the hostile sword again we'll shatter;

else why, as gleaming sickles bend,

we raise as one our mighty hammer?

Mount higher, thought, nor fear to drop,

but pierce the cold of stellar spaces.

O cosmic sickle, reap truth's crop!

Break mystery's hold, thou cosmic hammer!

Earth's old! For lies we hold no brief!

As in the fall, ripe fruits we gather.

Bind us, 0 sickle, in single sheaf!

In single plinth, 0 forge us, hammer!

But fair outmirrored to the view,

the soul of man is young and happy.

The sickle whet for harvests new,

for coming battles keep the hammer.

(1921)

Padraic Breslin

The grandson of a former serf, Valery Yakovlevich Bryusov was born in Moscow. From his schooldays he read widely; as a young man he was determined to make his mark on the literary world. In a diary entry from 1893 he wrote, 'Whether Decadence is false or ridiculous, it is moving forward, developing, and the future will belong to it when it finds a worthy leader. And that leader will be me! Yes, me!"

From 1894 to 1895 Bryusov published three collections of poems entitled Russian Symbolists: An Anthology; most of the poems were his own, but he used a number of pseudonyms to make this new 'Decadent' or 'Symbolist' movement seem more impressive. These anthologies also included Bryusov's translations of such poets as Poe, Mallarrne, Verlaine, Oscar Wilde and Emile Verhaeren.

Bryusov was influential not only as the founder, with Konstantin Balmont, of Russian Symbolism but also as an editor. From 1904 he ran the Skorpion publishing house, and from 1904 until 1909 he also edited the influential journal The Scales. In 1908 he published a historical novel, The Fiery Angel, which Prokofiev later used for an opera libretto. Bryusov's capacity for work was extraordinary. In 1915 he was asked to compile a large anthology of Russian translations of Armenian poetry: he learned the language, read a great deal of background literature and completed most of the translations in less than a year.

In late 1917, when many of his literary colleagues were emigrating, Bryusov declared his support for the Soviet government. In 1920 he joined the Communist Party. There are several accounts of his abusing his position in the Soviet cultural apparatus to attack more gifted colleagues - Khodasevich and Mandelstam among them - of whom he felt envious.

Bryusov is a dull poet. We include the following poem because it has been so well translated by Padraic Breslin, who deserves to be remembered.

*

What if we suffered from the lash

of black defeat and cold and hunger?

Above the world new symbols flash,

the sickle and the workers' hammer.

The soil again our toil will tend,

the hostile sword again we'll shatter;

else why, as gleaming sickles bend,

we raise as one our mighty hammer?

Mount higher, thought, nor fear to drop,

but pierce the cold of stellar spaces.

O cosmic sickle, reap truth's crop!

Break mystery's hold, thou cosmic hammer!

Earth's old! For lies we hold no brief!

As in the fall, ripe fruits we gather.

Bind us, 0 sickle, in single sheaf!

In single plinth, 0 forge us, hammer!

But fair outmirrored to the view,

the soul of man is young and happy.

The sickle whet for harvests new,

for coming battles keep the hammer.

(1921)

Padraic Breslin

from Civil War

And from the ranks of both armies -

the same voice, the same refrain:

'He who is not with us is against us.

You must take sides. Justice is ours.'

And I stand alone in the midst of them,

amidst the roar of fire and smoke,

and pray with all my strength for those

who fight on this side, and on that side.

(1919)

Maximilian Voloshin (1877-1932)

Robert Chandler

the same voice, the same refrain:

'He who is not with us is against us.

You must take sides. Justice is ours.'

And I stand alone in the midst of them,

amidst the roar of fire and smoke,

and pray with all my strength for those

who fight on this side, and on that side.

(1919)

Maximilian Voloshin (1877-1932)

Robert Chandler

từ Nội Chiến

Và từ những hàng ngũ của hai bên

Cùng 1 giọng, cùng 1 điệp khúc:

Kẻ nào không theo ta, là chống ta

Mi phải chọn bên.

Công lý là của chúng ta/chúng ông!

Và đứng giữa chúng

Là GCC

Viết đến gãy cả ngòi viết

Cầu nguyện cho cả hai

Bắc Kít và Nam Kít!

Và từ những hàng ngũ của hai bên

Cùng 1 giọng, cùng 1 điệp khúc:

Kẻ nào không theo ta, là chống ta

Mi phải chọn bên.

Công lý là của chúng ta/chúng ông!

Và đứng giữa chúng

Là GCC

Viết đến gãy cả ngòi viết

Cầu nguyện cho cả hai

Bắc Kít và Nam Kít!

http://www.tanvien.net/new_daily_poetry/strong_wods_A_A.html

Strong

Words

O, some spoken words need stay unspoken!

Some writers should bite their tongues;

Only the blue dome of the sky and God

In His infinite mercy are inexhaustible.

Từ Dữ Dằn

Ôi, vài từ nói cần đừng nói

Vài nhà văn nên cắn lưỡi của họ

Chỉ vòm trời xanh

Và Chúa

Trong cái rộng lượng vô cùng của Người

Là chẳng bao giờ cạn láng

https://ninablog2008.wordpress.com/category/van-hoa/thi-ca-nga/akhmatova-anna/

Hôm nay là

kỷ niệm ngày Anna Akhmatova qua đời – tròn 50 năm trước…

Writhing with anxiety, and in tears,

Hands laid on a wound so congealed,

So black, it cannot be healed.

Why such sun showers in the West?

Such a play of light across city roofs?

A scythe scores our doors with a cross

Calling for crows. And they are flying.

1919

Anna Akhmatova

Thế kỷ này tệ hại gì hơn trước?

- Trong khói mù lo lắng với đau buồn

Nó chạm đến vết loét đen tối nhất,

Nhưng không thể nào chữa được vết thương.

Phía tây mặt trời còn đang chiếu sáng

Những mái nhà lấp lánh dưới nắng vàng,

Cái chết trắng nơi đây phá tung nhà cửa

Hú gọi quạ bầy, và đàn quạ bay sang.

Dịch từ nguyên tác

https://www.facebook.com/luusanina?fref=nf

Tks

Bản tiếng Anh có tí khác. Dịch "thoáng":

Quằn quại với âu lo, với nước mắt

Tay đặt lên vết thương đóng khằn

Đen thui, không làm sao lành nổi!

Tại sao mặt trời rực rỡ như thế đó, ở phía Tây?

Ánh sáng chói chang trên những mái nhà

Một cái liềm đi 1 đường chữ thập lên những cánh cửa

Hú gọi quạ

Và chúng bèn bay tới

Note:

Bài thơ này, sợ có tí ẩn dụ, như bản tiếng Anh cho thấy.

Anna Akhmatova, cũng thứ cực kỳ thông minh, nhưng không chọn cách bỏ đi. Bài thơ tả nước Nga của bà, so sánh thời của bà, với những thời kỳ khác. Thì ai cũng so sánh, nhất là thi sĩ.

Osip Mandelstam cũng có 1 bài không hẳn tương tự, trong "tiếng động của thời gian", "le bruit du temps", và nỗi hoài nhớ quá khứ ám ảnh ông:

Người ta sống khá hơn, trước đây

Thật ra, người ta không thể so sánh

Máu bây giờ

Và máu ngày xưa

Nó rù rì khác nhau như thế nào.

On vivait mieux auparavant

A vrai dire, on ne peut pas comparer

Comme le sang ruisselait alors

Et comme il bruit maintenant.

[Trích Tiếng động thời gian, bản tiếng Tây, lời giới thiệu].

Tuy nhiên, chẳng bao giờ bà chọn cách bỏ chạy, như trong Kinh Cầu cho thấy

Kinh Cầu - Requiem

No, it wasn't under a foreign heaven,

It wasn't under the wing of a foreign power,-

I was there among my countrymen

I was where my people, unfortunately, were

[Không, không phải dưới bầu trời xa lạ,

Không phải dưới đôi cánh của quyền lực xa lạ, -

Tôi ở đó, giữa đồng bào của tôi

Nơi tôi ở, là nơi đồng bào tôi, bất hạnh thay, ở]

1961

Tôi làm sao chịu nổi nỗi đau đó

Hãy choàng nó bằng vải liệm đen

Và mang đèn đi chỗ khác

Đêm rồi!

Akhmatova: Kinh Cầu

INTRODUCTION

This happened when only the dead wore smiles--

They rejoiced at being safe from harm.

And Leningrad dangled from its jails

Like some unnecessary arm.

And when the hosts of those convicted,

Marched by-mad, tormented throngs,

And train whistles were restricted

To singing separation songs.

The stars of death stood overhead,

And guiltless Russia, that pariah,

Writhed under boots, all blood-bespattered,

And the wheels of many a black maria.

1935

3.

No, this isn't me, someone else suffers,

I couldn't stand it. All that's happened

They should wrap up in black covers,

The streetlights should be taken away ...

Night.

1939

At exactly twelv.e noon, Sunday.

It was quiet in the wide room.

Outside, freezing cold.

A raspberry sun

Trailed tatters of blue smoke ...

That sun, like my laconic host,

Cast a slant eye on me!

A host whose eyes

No one can forget;

Best be careful,

Don't look into them at all.

But I do recall how we talked

That Sunday noon, how we sat

Smoking in the tall grey house

By the mouth of the Neva.

Tôi tới gặp nhà thơ

Vào đúng ngọ, Chủ Nhật.

Trong căn phòng rộng, êm ả

Ngoài trời lạnh giá

Mặt trời hồng vạch một đường khói xanh…

Nó giống vị chủ nhà gọn gàng

Ném 1 cái nhìn xéo lên tôi!

Vị chủ nhà với cặp mắt

Không một ai có thể quên được

Tốt nhất, hãy coi chừng

Đừng nhìn vào mắt ông ta

Nhưng làm sao mà tôi không nhớ lại

Cuộc trò chuyện bữa trưa Chủ Nhật đó

Như thế nào chúng tôi ngồi hút thuốc

Trong căn nhà màu xám, cao

Kế cửa sông Neva

Vladislav Khodasevich (1886-1939)

Janus

In me things end, and start again.

I am, although my work is slight,

a link in an unbroken chain -

one joy, at least, is mine by right.

And come the day my country's great

again, you'll see my statue stand

beside a place where four roads meet

with wind, and time, and spreading sand.

(1 January 1928)

Robert Chandler

The Monument

I am an end and a beginning.

So little spun from all my spinning!

I've been a firm link nonetheless;

with that good fortune I've been blessed.

New Russia enters on her greatness;

they'll carve my head two-faced, like Janus,

at crossroads, looking down both ways,

where wind and sand, and many days ...

Michael Frayn

Janus: Vị thần hai mặt.

Đây là bộ mặt của PXA, vào đúng ngày 30 Tháng Tư, 1975, khi anh đứng nhìn VC vô Saigon, qua miêu tả của 1 ký giả nước ngoài. Từ "Janus", là của ký giả này, không phải của GCC, nhưng cái hình ảnh 1 Janus, như trong bài thơ, trên, thì là giấc mơ của hắn:

Bạn sẽ nhìn thấy bức tượng của thằng chả, ở nơi ngã tư đường, với gió, thời gian và cát bụi bay búa xua....

Đó là ngày xứ Mít lại bảnh tỏng

Time's publetter celebrated his decision to stay and published a picture of him standing on a now deserted street smoking a cigarette and looking pugnacious.

Time tán dương quyết định ở lại của Phạm Xuân Ẩn và đăng hình ông, với vẻ mặt căng thẳng, đứng hút thuốc lá giữa con phố hoang vắng của Sài Gòn.

Tuyệt cú mèo! Thành phố này giờ này thuộc về ta, vị thần Janus hai mặt!

Ẩn hả, nhớ chứ!

"After all, there is such a thing as truth"

[Nói cho cùng, có cái thứ đó, một cái gì từa tựa như là sự thực]

Victor Serge: Trường hợp Đồng chí Tulayev

Susan Sontag trích dẫn làm đề từ cho bài viết về

Victor Serge: Không bị vùi giập [Unextinguished]: Trường hợp Victor Serge

*

Sontag viết:

Làm sao giải thích sự chìm vào tối tăm quên lãng của một trong những vị anh hùng bảnh nhất, cả về đạo hạnh lẫn văn chương của thế kỷ 20: Victor Serge? Làm thế nào mà hiểu được cái sự lơ là không được biết đến của cuốn Trường hợp Đồng chí Tulayev, một cuốn tiểu thuyết tuyệt vời, đã từng được lại khám phá ra, rồi lại chìm vào quên lãng, ngay từ khi vừa được xuất bản, một năm sau khi ông mất, 1947?

Phải chăng, đó là do không có xứ sở nào nhận [claim] ông ?

Janus

Trong tớ mọi chuyện tận cùng, và lại bắt đầu.

Tớ là, dù tác phẩm nhẹ hều,

mối nối của sợi sên không bị bẻ gãy –

một niềm vui, ít ra, là của tớ, quyền của tớ

Và tới cái ngày cái nhà của xứ Mít của tớ lại lớn lao

Bạn sẽ nhìn thấy bức tượng của tớ bên công viên

Nơi bốn con đường tụ lại

Với gió, thời gian và cát trải dài

Bài thơ này dành tặng Cao Bồi PXA, “bạn quí của Gấu” một thời, quá tuyệt.

Lạ, là làm sao mà cái tên ký giả mũi lõ nào đó, viết về PXA, ngày 30 Tháng Tư 1975, nhìn ngay ra cái dáng đứng hai mặt của chàng.

Quá bảnh!

Đài Tưởng Niệm

Tớ là tận cùng và là bắt đầu.

Suốt đời chỉ có mấy cái truyện ngắn, lập đi lập lại, chỉ mỗi chuyện Mậu Thân, và thằng em trai tử trận

Tớ là cái link vững chãi tuy nhiên, đúng như thế.

Chính là nhớ tí truyện ngắn viết từ thời còn trẻ tuổi

Và mấy bài thơ, nhờ gặp lại cô bạn nơi xứ người, sau bỏ chạy được quê hương,

Mà tớ được chúc phúc

Một xứ Mít mới tinh, bảnh tỏng đi vào cái sự vĩ đại của nó

Họ bèn khắc bức tượng hai mặt của tớ, như Janus

Ở Ngã Tư Hàng Xanh, nhìn về cả hai phiá,

Một, Hà Nội, ngày nào

Một, Sài Gòn ngày này - trước và sau 30 Tháng Tư 1975 - ngày mai, ngày mãi mãi

Nơi gió, cát, và rất nhiều ngày…

Mình ko có liên hệ gì với mãnh tướng 1 thời của miền Nam là ô Đỗ Cao Trí, người có tiếng là vào sanh ra tử.

Năm 1974, mình đi nhổ răng khôn tại trường Nha Sàigòn, GS Trương Như Sản động viên mình bằng cách kể "Ngồi lên chiếc ghế này, tới tướng Trí còn phải sợ!"

Từ đó mỗi lần đi nha sĩ, mình lại nhớ đến tướng Trí và bác Sản. Hôm nay cấy 2 răng và nhổ 1 cái hàm, sau đó có nỗ lực đến VietFimFest chào các bạn là dũng cảm!

Note: Đọc mẩu trên, thì nhân tiện, bèn nhớ ra mẩu này:

Giải hoặc

Cảm ơn anh Hòa Nguyễn đã quan tâm đến những bài viết của tôi, đã đọc kỹ bài về Đỗ Kh. Tôi trả lời với tất cả sự nghiêm chỉnh.

Chữ "giải hoặc", tôi dùng theo nghĩa: giải thoát tư duy ra khỏi huyễn hoặc của huyền thoại.

Từ này thông dụng ở miền Nam trước 1975. Nguyễn Văn Trung ưa dùng, có lẽ do chính ông đặt ra để dịch chữ démystification, cũng như ông dùng từ "giải thực" để dịch décolonisation. Từ "giải hoặc", ngoài ý nghĩa nghiêm chỉnh như trên, còn có khi đuợc dùng để đùa vui: "giải hoặc rồi" có nghĩa "sáng mắt ra rồi"; dường như trong kịch vui Ngộ nhận, mà tác giả Vũ Khắc Khoan gọi là "lộng ngôn", ông có dùng theo nghĩa đùa vui này. Gặp dịp, tình cờ thôi, tôi hồn nhiên dùng lại. Nay anh Hòa Nguyễn hỏi, tôi mới được "giải hoặc": mở các từ điển tiếng Việt hiện hành, không có "giải hoặc", "giải thực" gì ráo! Chuyện nhỏ thôi, nhưng cũng là kinh nghiệm cho người viết văn: những chữ mình cho là đơn giản, vì quen dùng, chưa chắc gì mọi người đã biết.

Về một vài thắc mắc khác: tình yêu là thực chất, có lúc xen vào huyền thoại; bản năng sinh lý, tình dục, dĩ nhiên là thực chất, cũng có lúc xen vào hoang tưởng, nghĩa là thuyền thoại. Đề tài này sâu xa và phức tạp, khó lý giải ở đây – và cả nơi khác.

Về trường hợp Nguyễn Huy Thiệp đã phá huyền thoại này lại rơi vào huyền thoại khác, như tôi gợi ý, là vì ông ấy nghiêm trang. Còn Đỗ Kh. thì tếu. Ông Đỗ Kh. không phải là "bậc siêu xuất" hoặc "bậc giác ngộ", mà chỉ quan sát con người, có lẽ chủ yếu là cộng đồng di dân, rồi đưa ra một vài nhận xét phúng thế.

Tập truyện Đỗ Kh. xuất bản 1993 tại hải ngoại, bài điểm sách của tôi đăng trên một tạp chí hải ngoại 1994: vào thời điểm ấy, bài ấy, sách ấy là cần thiết. Mục đích của tôi không phải là đề cao Đỗ Kh., nhất là "đề cao hơi quá" về mặt nội dung giải hoặc; mà để đáp ứng lại môt nhu cầu tâm lý lúc ấy.

Anh Hòa Nguyễn có thể trách tôi: đưa ra tiêu đề "Đỗ Kh., kẻ giải hoặc", là đã vô hình trung tạo một huyền thoại Đỗ Kh. Nói vậy thì tôi chịu, không cãi vào đâu được.

Nhưng cũng sẽ vui thôi.

Đặng Tiến

Nguồn talawas

*

Bạn hiền nhận xét như thế này, thì hơi bị nhảm, và có tí thiên vị. Đỗ Kh. và NHT là hai trường hợp hoàn toàn khác biệt. Một hơi bị hề, một quá nghiêm trọng, vì động tới mồ tới mả của một miền đất, đụng tới cái gọi là tội tổ tông.

Không phải tự nhiên mà NHT cho NH ra Bắc nhét cái gì đó vào miệng tụi nó cho tao.

Nhét cái gì đó, mà không giải hoặc được, thì lại nhét tiếp!

Có thể, sau này NHT không còn là NHT. Nhưng đâu cần!

Đúng, ông Đỗ Kh không phải là bậc siêu xuất, hoặc bậc giác ngộ. Ông là Đỗ Kh.

Những nhận xét phúng thế? Chưa chắc. Bạn ta, đúng như bạn ĐT nói, chỉ vui thôi mà!

Lạ, trên bạn viết "với tất cả sự nghiêm chỉnh", dưới, bạn "vui thôi mà".

Suy ra, "vui thôi mà" là "nghiêm chỉnh"? NQT

O, some spoken words need stay unspoken!

Some writers should bite their tongues;

Only the blue dome of the sky and God

In His infinite mercy are inexhaustible.

Từ Dữ Dằn

Ôi, vài từ nói cần đừng nói

Vài nhà văn nên cắn lưỡi của họ

Chỉ vòm trời xanh

Và Chúa

Trong cái rộng lượng vô cùng của Người

Là chẳng bao giờ cạn láng

https://ninablog2008.wordpress.com/category/van-hoa/thi-ca-nga/akhmatova-anna/

| * * * Анна Ахматова Отодвинув мечты и устав от идей, Жду зимы как другие не ждут. Помнишь, ты обещал, что не будет дождей? А они всё идут и идут… Удивлённо смотрю из квартирных окон- Я во сне или всё ж наяву? Помнишь, ты говорил, что вся жизнь – это сон? Я проснулась, и странно, живу… А назавтра опять мне играть свою роль, И смеяться опять в невпопад. Помнишь, ты говорил, что любовь – это боль?! Ты ошибся, любовь – это ад… |

*

* * Anna Akhmatova Mệt vì ý tưởng, gạt ước mơ qua, Em đợi mùa đông, như người ta không đợi. Anh có nhớ, anh hứa, mưa không tới? Nhưng bây giờ mưa vẫn tuôn rơi… Em ngạc nhiên nhìn từ khung cửa sổ – Em đang mơ, hay thực tại là đây? Anh có nhớ, anh nói, đời là mộng? Em tỉnh giấc rồi, mà vẫn sống, lạ thay… Rồi ngày mai em tiếp tục diễn vai, Và sẽ lại cười không phải lúc. Anh từng nói, tình yêu là nỗi đau? Anh nhầm rồi, tình yêu là địa ngục. |

Worse

Are we worse than

they were in their years? Writhing with anxiety, and in tears,

Hands laid on a wound so congealed,

So black, it cannot be healed.

Why such sun showers in the West?

Such a play of light across city roofs?

A scythe scores our doors with a cross

Calling for crows. And they are flying.

1919

Anna Akhmatova

Thế kỷ này tệ hại gì hơn trước?

- Trong khói mù lo lắng với đau buồn

Nó chạm đến vết loét đen tối nhất,

Nhưng không thể nào chữa được vết thương.

Phía tây mặt trời còn đang chiếu sáng

Những mái nhà lấp lánh dưới nắng vàng,

Cái chết trắng nơi đây phá tung nhà cửa

Hú gọi quạ bầy, và đàn quạ bay sang.

Dịch từ nguyên tác

https://www.facebook.com/luusanina?fref=nf

Tks

Bản tiếng Anh có tí khác. Dịch "thoáng":

Tệ

Hại

Thời của tụi mình

tệ hơn của tụi nó?Quằn quại với âu lo, với nước mắt

Tay đặt lên vết thương đóng khằn

Đen thui, không làm sao lành nổi!

Tại sao mặt trời rực rỡ như thế đó, ở phía Tây?

Ánh sáng chói chang trên những mái nhà

Một cái liềm đi 1 đường chữ thập lên những cánh cửa

Hú gọi quạ

Và chúng bèn bay tới

Note:

Bài thơ này, sợ có tí ẩn dụ, như bản tiếng Anh cho thấy.

Anna Akhmatova, cũng thứ cực kỳ thông minh, nhưng không chọn cách bỏ đi. Bài thơ tả nước Nga của bà, so sánh thời của bà, với những thời kỳ khác. Thì ai cũng so sánh, nhất là thi sĩ.

Osip Mandelstam cũng có 1 bài không hẳn tương tự, trong "tiếng động của thời gian", "le bruit du temps", và nỗi hoài nhớ quá khứ ám ảnh ông:

Người ta sống khá hơn, trước đây

Thật ra, người ta không thể so sánh

Máu bây giờ

Và máu ngày xưa

Nó rù rì khác nhau như thế nào.

On vivait mieux auparavant

A vrai dire, on ne peut pas comparer

Comme le sang ruisselait alors

Et comme il bruit maintenant.

[Trích Tiếng động thời gian, bản tiếng Tây, lời giới thiệu].

Tuy nhiên, chẳng bao giờ bà chọn cách bỏ chạy, như trong Kinh Cầu cho thấy

Kinh Cầu - Requiem

No, it wasn't under a foreign heaven,

It wasn't under the wing of a foreign power,-

I was there among my countrymen

I was where my people, unfortunately, were

[Không, không phải dưới bầu trời xa lạ,

Không phải dưới đôi cánh của quyền lực xa lạ, -

Tôi ở đó, giữa đồng bào của tôi

Nơi tôi ở, là nơi đồng bào tôi, bất hạnh thay, ở]

1961

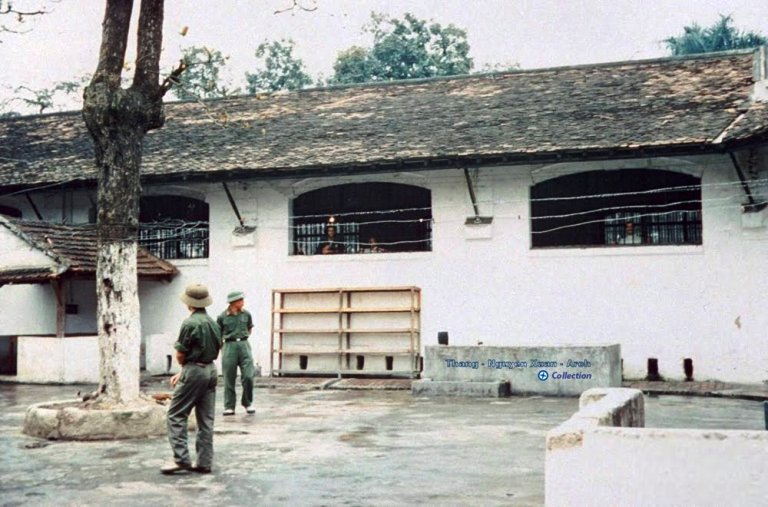

Khách sạn Hilton, Hà

Nội

Chẳng có ai người cười

nổi, những ngày đó

Ngoại trừ những người chết, sau cùng tìm thấy sự bình an

Như 1 cánh tay thừa thãi, 1 sức nặng vô dụng

Hà Nội đong đưa quanh Hỏa Lò

Hàng theo hàng, đám Ngụy diễu [không phải diễn] hành,

Khùng vì đau, nhắm nỗi bất hạnh của họ

Bài ca vĩnh biệt, sắc, gọn

Tiếng còi tầu chở súc vật rú lên

Ngôi sao thần chết đứng sững trên nền trời Hà Nội

Và xứ Bắc Kít, ngây thơ vô tội,

Quằn quại dưới gót giầy máu

Dưới bánh xe chở tù.

Không phải tôi. Ai đó đau khổNgoại trừ những người chết, sau cùng tìm thấy sự bình an

Như 1 cánh tay thừa thãi, 1 sức nặng vô dụng

Hà Nội đong đưa quanh Hỏa Lò

Hàng theo hàng, đám Ngụy diễu [không phải diễn] hành,

Khùng vì đau, nhắm nỗi bất hạnh của họ

Bài ca vĩnh biệt, sắc, gọn

Tiếng còi tầu chở súc vật rú lên

Ngôi sao thần chết đứng sững trên nền trời Hà Nội

Và xứ Bắc Kít, ngây thơ vô tội,

Quằn quại dưới gót giầy máu

Dưới bánh xe chở tù.

Tôi làm sao chịu nổi nỗi đau đó

Hãy choàng nó bằng vải liệm đen

Và mang đèn đi chỗ khác

Đêm rồi!

Akhmatova: Kinh Cầu

INTRODUCTION

This happened when only the dead wore smiles--

They rejoiced at being safe from harm.

And Leningrad dangled from its jails

Like some unnecessary arm.

And when the hosts of those convicted,

Marched by-mad, tormented throngs,

And train whistles were restricted

To singing separation songs.

The stars of death stood overhead,

And guiltless Russia, that pariah,

Writhed under boots, all blood-bespattered,

And the wheels of many a black maria.

1935

3.

No, this isn't me, someone else suffers,

I couldn't stand it. All that's happened

They should wrap up in black covers,

The streetlights should be taken away ...

Night.

1939

To Alexander Blok

I went

to see the poet At exactly twelv.e noon, Sunday.

It was quiet in the wide room.

Outside, freezing cold.

A raspberry sun

Trailed tatters of blue smoke ...

That sun, like my laconic host,

Cast a slant eye on me!

A host whose eyes

No one can forget;

Best be careful,

Don't look into them at all.

But I do recall how we talked

That Sunday noon, how we sat

Smoking in the tall grey house

By the mouth of the Neva.

Gửi Alexander Blok

Tôi tới gặp nhà thơ

Vào đúng ngọ, Chủ Nhật.

Trong căn phòng rộng, êm ả

Ngoài trời lạnh giá

Mặt trời hồng vạch một đường khói xanh…

Nó giống vị chủ nhà gọn gàng

Ném 1 cái nhìn xéo lên tôi!

Vị chủ nhà với cặp mắt

Không một ai có thể quên được

Tốt nhất, hãy coi chừng

Đừng nhìn vào mắt ông ta

Nhưng làm sao mà tôi không nhớ lại

Cuộc trò chuyện bữa trưa Chủ Nhật đó

Như thế nào chúng tôi ngồi hút thuốc

Trong căn nhà màu xám, cao

Kế cửa sông Neva

Vladislav Khodasevich (1886-1939)

Janus

In me things end, and start again.

I am, although my work is slight,

a link in an unbroken chain -

one joy, at least, is mine by right.

And come the day my country's great

again, you'll see my statue stand

beside a place where four roads meet

with wind, and time, and spreading sand.

(1 January 1928)

Robert Chandler

The Monument

I am an end and a beginning.

So little spun from all my spinning!

I've been a firm link nonetheless;

with that good fortune I've been blessed.

New Russia enters on her greatness;

they'll carve my head two-faced, like Janus,

at crossroads, looking down both ways,

where wind and sand, and many days ...

Michael Frayn

Janus: Vị thần hai mặt.

Đây là bộ mặt của PXA, vào đúng ngày 30 Tháng Tư, 1975, khi anh đứng nhìn VC vô Saigon, qua miêu tả của 1 ký giả nước ngoài. Từ "Janus", là của ký giả này, không phải của GCC, nhưng cái hình ảnh 1 Janus, như trong bài thơ, trên, thì là giấc mơ của hắn:

Bạn sẽ nhìn thấy bức tượng của thằng chả, ở nơi ngã tư đường, với gió, thời gian và cát bụi bay búa xua....

Đó là ngày xứ Mít lại bảnh tỏng

Time's publetter celebrated his decision to stay and published a picture of him standing on a now deserted street smoking a cigarette and looking pugnacious.

Time tán dương quyết định ở lại của Phạm Xuân Ẩn và đăng hình ông, với vẻ mặt căng thẳng, đứng hút thuốc lá giữa con phố hoang vắng của Sài Gòn.

Tuyệt cú mèo! Thành phố này giờ này thuộc về ta, vị thần Janus hai mặt!

Ẩn hả, nhớ chứ!

Gấu & Tư Long & cận vệ

Hình chụp ngay sau 30 Tháng Tư 1975, tại Sở Thú. Vừa giải phóng xong là ông cậu tập kết ghé nhà hỏi thăm liền.

Tư Long, Cậu Tư của Gấu Cái. Nhờ ông này, Gấu thoát nhà tù Bà Bèo.

Ngoài Bắc thì có ông cậu Toàn.

*Hình chụp ngay sau 30 Tháng Tư 1975, tại Sở Thú. Vừa giải phóng xong là ông cậu tập kết ghé nhà hỏi thăm liền.

Tư Long, Cậu Tư của Gấu Cái. Nhờ ông này, Gấu thoát nhà tù Bà Bèo.

Ngoài Bắc thì có ông cậu Toàn.

"After all, there is such a thing as truth"

[Nói cho cùng, có cái thứ đó, một cái gì từa tựa như là sự thực]

Victor Serge: Trường hợp Đồng chí Tulayev

Susan Sontag trích dẫn làm đề từ cho bài viết về

Victor Serge: Không bị vùi giập [Unextinguished]: Trường hợp Victor Serge

*

Sontag viết:

Làm sao giải thích sự chìm vào tối tăm quên lãng của một trong những vị anh hùng bảnh nhất, cả về đạo hạnh lẫn văn chương của thế kỷ 20: Victor Serge? Làm thế nào mà hiểu được cái sự lơ là không được biết đến của cuốn Trường hợp Đồng chí Tulayev, một cuốn tiểu thuyết tuyệt vời, đã từng được lại khám phá ra, rồi lại chìm vào quên lãng, ngay từ khi vừa được xuất bản, một năm sau khi ông mất, 1947?

Phải chăng, đó là do không có xứ sở nào nhận [claim] ông ?

Janus

Trong tớ mọi chuyện tận cùng, và lại bắt đầu.

Tớ là, dù tác phẩm nhẹ hều,

mối nối của sợi sên không bị bẻ gãy –

một niềm vui, ít ra, là của tớ, quyền của tớ

Và tới cái ngày cái nhà của xứ Mít của tớ lại lớn lao

Bạn sẽ nhìn thấy bức tượng của tớ bên công viên

Nơi bốn con đường tụ lại

Với gió, thời gian và cát trải dài

Bài thơ này dành tặng Cao Bồi PXA, “bạn quí của Gấu” một thời, quá tuyệt.

Lạ, là làm sao mà cái tên ký giả mũi lõ nào đó, viết về PXA, ngày 30 Tháng Tư 1975, nhìn ngay ra cái dáng đứng hai mặt của chàng.

Quá bảnh!

Đài Tưởng Niệm

Tớ là tận cùng và là bắt đầu.

Suốt đời chỉ có mấy cái truyện ngắn, lập đi lập lại, chỉ mỗi chuyện Mậu Thân, và thằng em trai tử trận

Tớ là cái link vững chãi tuy nhiên, đúng như thế.

Chính là nhớ tí truyện ngắn viết từ thời còn trẻ tuổi

Và mấy bài thơ, nhờ gặp lại cô bạn nơi xứ người, sau bỏ chạy được quê hương,

Mà tớ được chúc phúc

Một xứ Mít mới tinh, bảnh tỏng đi vào cái sự vĩ đại của nó

Họ bèn khắc bức tượng hai mặt của tớ, như Janus

Ở Ngã Tư Hàng Xanh, nhìn về cả hai phiá,

Một, Hà Nội, ngày nào

Một, Sài Gòn ngày này - trước và sau 30 Tháng Tư 1975 - ngày mai, ngày mãi mãi

Nơi gió, cát, và rất nhiều ngày…

Mình ko có liên hệ gì với mãnh tướng 1 thời của miền Nam là ô Đỗ Cao Trí, người có tiếng là vào sanh ra tử.

Năm 1974, mình đi nhổ răng khôn tại trường Nha Sàigòn, GS Trương Như Sản động viên mình bằng cách kể "Ngồi lên chiếc ghế này, tới tướng Trí còn phải sợ!"

Từ đó mỗi lần đi nha sĩ, mình lại nhớ đến tướng Trí và bác Sản. Hôm nay cấy 2 răng và nhổ 1 cái hàm, sau đó có nỗ lực đến VietFimFest chào các bạn là dũng cảm!

Note: Đọc mẩu trên, thì nhân tiện, bèn nhớ ra mẩu này:

Giải hoặc

Cảm ơn anh Hòa Nguyễn đã quan tâm đến những bài viết của tôi, đã đọc kỹ bài về Đỗ Kh. Tôi trả lời với tất cả sự nghiêm chỉnh.

Chữ "giải hoặc", tôi dùng theo nghĩa: giải thoát tư duy ra khỏi huyễn hoặc của huyền thoại.

Từ này thông dụng ở miền Nam trước 1975. Nguyễn Văn Trung ưa dùng, có lẽ do chính ông đặt ra để dịch chữ démystification, cũng như ông dùng từ "giải thực" để dịch décolonisation. Từ "giải hoặc", ngoài ý nghĩa nghiêm chỉnh như trên, còn có khi đuợc dùng để đùa vui: "giải hoặc rồi" có nghĩa "sáng mắt ra rồi"; dường như trong kịch vui Ngộ nhận, mà tác giả Vũ Khắc Khoan gọi là "lộng ngôn", ông có dùng theo nghĩa đùa vui này. Gặp dịp, tình cờ thôi, tôi hồn nhiên dùng lại. Nay anh Hòa Nguyễn hỏi, tôi mới được "giải hoặc": mở các từ điển tiếng Việt hiện hành, không có "giải hoặc", "giải thực" gì ráo! Chuyện nhỏ thôi, nhưng cũng là kinh nghiệm cho người viết văn: những chữ mình cho là đơn giản, vì quen dùng, chưa chắc gì mọi người đã biết.

Về một vài thắc mắc khác: tình yêu là thực chất, có lúc xen vào huyền thoại; bản năng sinh lý, tình dục, dĩ nhiên là thực chất, cũng có lúc xen vào hoang tưởng, nghĩa là thuyền thoại. Đề tài này sâu xa và phức tạp, khó lý giải ở đây – và cả nơi khác.

Về trường hợp Nguyễn Huy Thiệp đã phá huyền thoại này lại rơi vào huyền thoại khác, như tôi gợi ý, là vì ông ấy nghiêm trang. Còn Đỗ Kh. thì tếu. Ông Đỗ Kh. không phải là "bậc siêu xuất" hoặc "bậc giác ngộ", mà chỉ quan sát con người, có lẽ chủ yếu là cộng đồng di dân, rồi đưa ra một vài nhận xét phúng thế.

Tập truyện Đỗ Kh. xuất bản 1993 tại hải ngoại, bài điểm sách của tôi đăng trên một tạp chí hải ngoại 1994: vào thời điểm ấy, bài ấy, sách ấy là cần thiết. Mục đích của tôi không phải là đề cao Đỗ Kh., nhất là "đề cao hơi quá" về mặt nội dung giải hoặc; mà để đáp ứng lại môt nhu cầu tâm lý lúc ấy.

Anh Hòa Nguyễn có thể trách tôi: đưa ra tiêu đề "Đỗ Kh., kẻ giải hoặc", là đã vô hình trung tạo một huyền thoại Đỗ Kh. Nói vậy thì tôi chịu, không cãi vào đâu được.

Nhưng cũng sẽ vui thôi.

Đặng Tiến

Nguồn talawas

*

Bạn hiền nhận xét như thế này, thì hơi bị nhảm, và có tí thiên vị. Đỗ Kh. và NHT là hai trường hợp hoàn toàn khác biệt. Một hơi bị hề, một quá nghiêm trọng, vì động tới mồ tới mả của một miền đất, đụng tới cái gọi là tội tổ tông.

Không phải tự nhiên mà NHT cho NH ra Bắc nhét cái gì đó vào miệng tụi nó cho tao.

Nhét cái gì đó, mà không giải hoặc được, thì lại nhét tiếp!

Có thể, sau này NHT không còn là NHT. Nhưng đâu cần!

Đúng, ông Đỗ Kh không phải là bậc siêu xuất, hoặc bậc giác ngộ. Ông là Đỗ Kh.

Những nhận xét phúng thế? Chưa chắc. Bạn ta, đúng như bạn ĐT nói, chỉ vui thôi mà!

Lạ, trên bạn viết "với tất cả sự nghiêm chỉnh", dưới, bạn "vui thôi mà".

Suy ra, "vui thôi mà" là "nghiêm chỉnh"? NQT

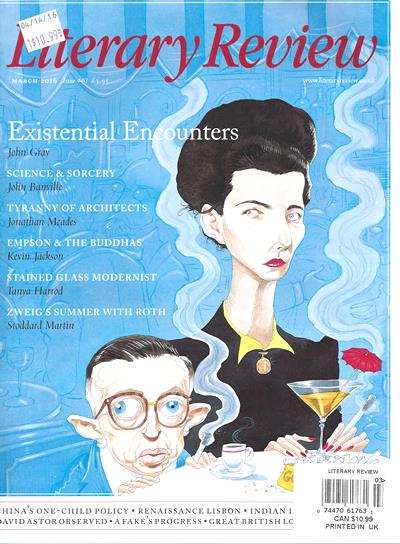

http://www.economist.com/news/books-and-arts/21695369-fun-and-philosophy-paris-smokey-and-bandits

EXISTENTIALISM is the only philosophy that anyone would even think of calling sexy. Black clothes, “free love”, late nights of smoky jazz—these were a few of intellectuals’ favourite things in Paris after the Simone de Beauvoir was “the prettiest Existentialist you ever saw”, according to the New Yorker in 1947. Her companion, Jean-Paul Sartre (pictured) was no looker, but he smoked a mean Gauloise. Life magazine billed their friend, Albert Camus, the “action-packed intellectual”.

Certainly there was action. One evening in Paris, a restaurant punch-up involving Sartre, Camus, de Beauvoir and Arthur Koestler spilled out on to the streets. In New York another novelist, Norman Mailer, drunkenly stabbed his wife at the launch of his abortive campaign to run for mayor on an “Existentialist Party” ticket in 1960. In addition to such excitements, existentialism offered a rationale for the feeling that life is absurd.

Countless adolescents, both young and old, have discovered the joys of angst through the writings of Sartre and his ilk. In her instructive and entertaining study of these thinkers and their hangers-on, Sarah Bakewell, a British biographer, tells how she was drawn as a teenager to Sartre’s “Nausea” because it was described on the cover as “a novel of the alienation of personality and the mystery of being”.

It was over apricot cocktails on the Rue Montparnasse that Sartre and de Beauvoir glimpsed a novel way to explore such mysteries. The year was 1932, and their friend Raymond Aron, a political scientist and philosopher, had just returned from Germany with news of the “phenomenology” of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. “If you are a phenomenologist,” Aron explained, “you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it!” The idea was to glean the essence of things by closely observing one’s own experience of them, preferably in mundane settings. Sartre and de Beauvoir set out to do just that.

Drawing on considerable personal knowledge, Sartre delved into “the meaning of the act of smoking”, among other things. Observing the behavioural tics of waiters, he noted that they sometimes seemed to be play-acting at being waiters. This led to labyrinthine reflections on the nature of freedom and authenticity. De Beauvoir’s efforts were more focused. By dissecting female experience of everyday life, she illustrated the ways in which gender is shaped by self-consciousness and social expectations. Ms Bakewell plausibly suggests that de Beauvoir’s pioneering feminist work, “The Second Sex”, was the most broadly influential product of European café philosophy of the period.

When Norman Mailer was asked what existentialism meant to him, he reportedly answered, “Oh, kinda playing things by ear.” Serious existentialists, such as Sartre, earned their label by focusing on a sense of “existence” that is supposedly distinctive of humans. People are uniquely aware of—and typically troubled by—their own state of being, or so the theory goes. Human existence is thus not at all like the existence of brute matter, or, for that matter, like the existence of brutes. People, but not animals, find themselves thrown into the world, as existentialists liked to say. They are forced to make sense of it for themselves and to forge their own identities.

The café philosophers came to regard each other’s existence as particularly troubling. Except for Sartre and de Beauvoir, who remained an intellectually devoted pair until his death in 1980, the main characters in post-war French philosophy drifted apart with varying degrees of drama. So did the German philosophers who inspired them.

Sartre’s embrace of Soviet communism, which he abandoned only to endorse Maoism instead, led Aron to condemn him as “merciless towards the failings of the democracies but ready to tolerate the worst crimes as long as they are committed in the name of the proper doctrines”. Ms Bakewell credits the existentialist movement, broadly defined, with providing inspiration to feminism, gay rights, anti-racism, anti-colonialism and other radical causes. A few cocktails can, it seems, lead to unexpected things.

Existentialism

Smokey and the bandits

Fun and philosophy in Paris

Mar 26th 2016 | From the print edition

Quán Chùa ở Paris: Khói, Sex, và Hiện Sinh

Smokey and the bandits

Fun and philosophy in Paris

Mar 26th 2016 | From the print edition

Quán Chùa ở Paris: Khói, Sex, và Hiện Sinh

At the Existentialist Café:

Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails.

By Sarah Bakewell. Other Press; 439 pages; $25. Chatto & Windus; £16.99.

By Sarah Bakewell. Other Press; 439 pages; $25. Chatto & Windus; £16.99.

EXISTENTIALISM is the only philosophy that anyone would even think of calling sexy. Black clothes, “free love”, late nights of smoky jazz—these were a few of intellectuals’ favourite things in Paris after the Simone de Beauvoir was “the prettiest Existentialist you ever saw”, according to the New Yorker in 1947. Her companion, Jean-Paul Sartre (pictured) was no looker, but he smoked a mean Gauloise. Life magazine billed their friend, Albert Camus, the “action-packed intellectual”.

Certainly there was action. One evening in Paris, a restaurant punch-up involving Sartre, Camus, de Beauvoir and Arthur Koestler spilled out on to the streets. In New York another novelist, Norman Mailer, drunkenly stabbed his wife at the launch of his abortive campaign to run for mayor on an “Existentialist Party” ticket in 1960. In addition to such excitements, existentialism offered a rationale for the feeling that life is absurd.

Countless adolescents, both young and old, have discovered the joys of angst through the writings of Sartre and his ilk. In her instructive and entertaining study of these thinkers and their hangers-on, Sarah Bakewell, a British biographer, tells how she was drawn as a teenager to Sartre’s “Nausea” because it was described on the cover as “a novel of the alienation of personality and the mystery of being”.

It was over apricot cocktails on the Rue Montparnasse that Sartre and de Beauvoir glimpsed a novel way to explore such mysteries. The year was 1932, and their friend Raymond Aron, a political scientist and philosopher, had just returned from Germany with news of the “phenomenology” of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. “If you are a phenomenologist,” Aron explained, “you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it!” The idea was to glean the essence of things by closely observing one’s own experience of them, preferably in mundane settings. Sartre and de Beauvoir set out to do just that.

Drawing on considerable personal knowledge, Sartre delved into “the meaning of the act of smoking”, among other things. Observing the behavioural tics of waiters, he noted that they sometimes seemed to be play-acting at being waiters. This led to labyrinthine reflections on the nature of freedom and authenticity. De Beauvoir’s efforts were more focused. By dissecting female experience of everyday life, she illustrated the ways in which gender is shaped by self-consciousness and social expectations. Ms Bakewell plausibly suggests that de Beauvoir’s pioneering feminist work, “The Second Sex”, was the most broadly influential product of European café philosophy of the period.

When Norman Mailer was asked what existentialism meant to him, he reportedly answered, “Oh, kinda playing things by ear.” Serious existentialists, such as Sartre, earned their label by focusing on a sense of “existence” that is supposedly distinctive of humans. People are uniquely aware of—and typically troubled by—their own state of being, or so the theory goes. Human existence is thus not at all like the existence of brute matter, or, for that matter, like the existence of brutes. People, but not animals, find themselves thrown into the world, as existentialists liked to say. They are forced to make sense of it for themselves and to forge their own identities.

The café philosophers came to regard each other’s existence as particularly troubling. Except for Sartre and de Beauvoir, who remained an intellectually devoted pair until his death in 1980, the main characters in post-war French philosophy drifted apart with varying degrees of drama. So did the German philosophers who inspired them.

Sartre’s embrace of Soviet communism, which he abandoned only to endorse Maoism instead, led Aron to condemn him as “merciless towards the failings of the democracies but ready to tolerate the worst crimes as long as they are committed in the name of the proper doctrines”. Ms Bakewell credits the existentialist movement, broadly defined, with providing inspiration to feminism, gay rights, anti-racism, anti-colonialism and other radical causes. A few cocktails can, it seems, lead to unexpected things.

Bài Tạp Ghi đầu tiên của GCC, là viết về Quán Chùa Saigon. Và về đám bạn hữu Tiểu Thuyết Mới, Hiện Sinh và không khí văn chương của thời mới lớn của GCC @ Saigon

Vào cái thời bây giờ, cả ba tờ báo, Người Kinh Tế, Văn Học Tẩy, và tờ điểm sách Ăng Lê, đều viết về cái mùi hiện sinh thời đó, ở Paris, toát ra từ bướm de Beauvoir!

Có 1 thứ triết học, là, hiện sinh, mà cái mùi của nó, là, sexy!

EXISTENTIALISM is the only philosophy that anyone would even think of calling sexy. Black clothes, “free love”, late nights of smoky jazz—these were a few of intellectuals’ favourite things in Paris after the Simone de Beauvoir was “the prettiest Existentialist you ever saw”, according to the New Yorker in 1947.

Sài gòn bảnh hơn nhiều, có hơn 1 bướm de Beauvoir:

Bướm anh lên em nhé, mưa không ướt đất, bướm mèo đêm, lao vào lửa, bướm vết thương dậy thì, vòng tay học trò.

Ra tới hải ngoại, vẫn còn bướm, nhà có cửa khóa trái!

Epigram

Here the loveliest of young women fight

for the honor of marrying the hangmen;

here the righteous are tortured at night

and the resolute worn down by hunger.

(1928)

Robert Chandler

Anna Akhmatova

Thơ trào phúng

Đây là trận đấu đáng yêu nhất của những bà nội trợ trẻ

Cho niềm vinh dự có ông chồng là đao phủ

Đây là kẻ trung trực bị tra tấn hàng đêm

Và sự kiên quyết tả tơi, bởi cơn đói

Trần Hồng Tiệm

March 8 at 6:55pm

ngữ lục

ở nơi này những cô gái xinh nhất ganh nhau

lấy danh giá làm vợ những tên đao phủ

ở nơi này tra tấn những người công chính mỗi đêm thâu

và bỏ đói những ai kiên cường không khuất phục

1924 anna akhmatova

Эпиграмма

Здесь девушки прекраснейшие спорят

За честь достаться в жены палачам.

Здесь праведных пытают по ночам,

И голодом неутомимых морят.

1924 Анна Ахматова

https://www.facebook.com/donga01?fref=nf

At Pasternak's funeral. Chukovskaya overheard a conversation between two young people: "Now the last great Russian poet has died:' "No, there's still one left-Anna Akhmatova:" The speakers' admiration of Pasternak and Akhmatova, members of their grandparents' generation, was common among the young. In contrast to the many comfortable middle-aged people who found de-Stalinization disorienting, for those in their teens and twenties it was like a breath of fresh air. In their opinion, their parents' generation was discredited by its craven surrender to dictatorship. The most intelligent and sensitive among them hoped to root themselves in an alternate past, a more humane one, and found it in the achievements of Russian culture. To them, Akhmatova was a living link to that past, and they eagerly sought her out. She became the mentor of four young poets, Josef Brodsky, Anatoly Nayman, Dmitry Bobyshev, and Yevgeny Rein. Her status as the matriarch of Russian literature was tacitly acknowledged even by the regime, which in 1961 allowed a new collection of her poetry to be published under the title Poems, 1909-1960. Like all her previous books, this one sold out immediately. As Akhmatova proudly noted, "From 1940 to 1961 95,000 copies of my books were printed in the USSR and it was still impossible to buy a collection of my poetry'?

Anna Akhmatova: The Word That Causes Death’s Defeat, Poems of Memory

Ở đám tang của Pasternak, Chukoskaya thoáng nghe hai anh chàng trẻ tuổi than thở, nhà thơ lớn lao của Nga đã chết, không, còn 1 người.

Anna Akhmatova.

Cái sự ngưỡng mộ của đám trẻ đối với Pat và Anna Akhmatova, thì là hiển nhiên. Chúng tởm bố mẹ chúng, quá sợ Đảng, và nhìn quá cha mẹ, tới quá khứ của nước Nga.

Với chúng, Anna Akhmatova là cái "living link" đó.

Cái sự chịu ơn Tẫu của Bắc Kít, xóa sạch quá khứ của xứ Mít, khủng khiếp đến như thế, không phải đơn giản.

Bắc Kít mất sạch bốn ngàn năm văn hiến, vì thờ Tẫu làm Thầy.

Cái sự khủng khiếp sẽ còn kéo dài mãi mãi, vì cái tương lai không còn nơi bấu víu. Thử đọc văn chương Bắc Kít. Đám tiền chiến, chúng chê, trưởng giả, sa đọa, chúng đâu đọc được Nguyễn Tuân một phần là vậy, và chính Nguyễn Tuân sau 1945, cũng quy hàng Đảng.

Quá khứ chống Tẫu mất sạch.

Cái sự đào bới văn học Miền Nam trước 1975, là còn do lý do này: Chỉ còn có nó!

Không chỉ văn chương Miền Nam.

Trong nó, còn niềm tự hào của toàn xứ Mít, điều này mới quan trọng.

Cinque

3.

It’s true I always hated itWhen people pitied me.

But you felt pity, stated it –

The sun is new in my body

That why dawn is everywhere.

I can do miracles here and there,

That’s why!

1945-1946

Anna Akhmatova

Đúng là tôi luôn ghét

Khi thiên hạ thương hại tôi

Nhưng khi anh cảm thấy thương hại, thì nói mẹ ra đi!

Mặt trời, mới, trong tôi

Đâu đâu cũng có màu bình minh, là thế.

Tôi có thể tạo phép lạ, đây và đó,

Đó là lý do tại sao!

Cinque: The number five in cards or dice.

Answer

I'm certainly not a Sibyl;my life is clear as a stream.

I just don't feel like singing

to the rattle of prison keys.

(1930s)

Anna Akhmatova

Robert Chandler

Song Nam Tang shared Trần Hồng Tiệm's post.

5 hrs ·

Trần Hồng Tiệm

18 hrs ·

trả lời

tôi hoàn toàn không phải là đồng cốt

cuộc đời tôi trong vắt tựa suối nguồn

mà đơn giản tôi không muốn hát

dưới tiếng leng keng của khóa nhà tù

những năm 1930

anna akhmatova

Ответ

И вовсе я не пророчица,

Жизнь моя светла, как ручей.

А просто мне петь не хочется

Под звон тюремных ключей.

1930-е годы

Анна Ахматова

#thodichdonga #thongadonga

Note: Bản tiếng Anh, cũng vậy.

Có tí khác, tôi không muốn hát theo tiếng leng keng...

Do đọc ba chớp ba nháng, nên dịch trật.

Bài thơ Pasternak tưởng niệm Tsvetaeva cũng dịch trật, nhờ bạn K sửa giùm

Tks all and sorry abt that

NQT

Trả lời

Tôi chắc chắn không phải là 1 Sybil;Đời tôi thì trong sáng như là con suối

Tôi chỉ không thích nghe

Tiếng leng keng của chùm chìa khoá

Nhà tù

Sibyl, là bà đồng, như Mít gọi, người nói ra những sấm ngôn. Đây là nick của Akhmatova. Số phận của bà giống của Cassandra.

The sibyls were women that the ancient Greeks believed were oracles. The earliest sibyls, according to legend, prophesied at holy sites. Their prophecies were influenced by divine inspiration from a deity; originally at Delphi and Pessinos, the deities were chthonic deities. In later antiquity, various writers attested to the existence of sibyls in Greece, Italy, the Levant, and Asia Minor. [Wiki]

*

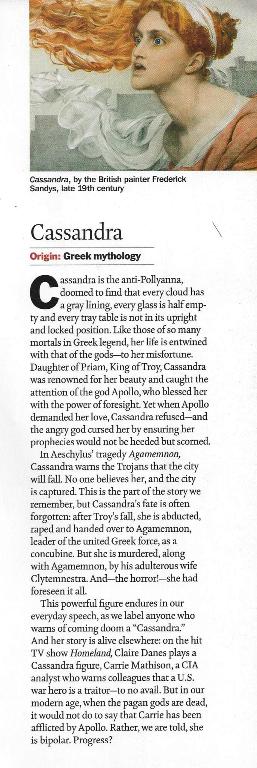

Cassandra, nhân vật trong thần thoại Hy Lạp, được thần Apollo ban cho tài tiên tri, nhưng do từ chối tình yêu của Apollo nên bị thần trù eỏ, mi tiên tri, nhưng đếch ai tin điều mi tiên tri.

Trong bi kịch Agamemnon của Aeschylus, Cassandra cảnh cáo đám Mít Miền Nam, đừng rước Yankee mũi tẹt vô, đừng đuổi Yankee mũi lõ. Đếch ai nghe. Thế là mất mẹ Miền Nam. Đến lúc đó, lời tiên tri mới thành hiện thực!

Nhưng ít người biết số phận của Cassandra, sau khi thành Troy bị mất. Em bị Yankee mũi tẹt bắt, hãm hiếp, và trao cho Víp Va Ka, Trùm VC nằm vùng, làm bồ nhí. Nhưng em bị ám sát, và thê thảm là, em nhìn thấy trước tất cả những điều này!

Hà, hà!

Số báo tuyệt vời, Tháng Tư 1975

"Tôi mang cái chết đến cho

những người thân của tôi

Hết người này tới người kia gục xuống.

Ôi đau đớn làm sao! Những nấm mồ

Đã được tôi báo trước bằng lời."

Hết người này tới người kia gục xuống.

Ôi đau đớn làm sao! Những nấm mồ

Đã được tôi báo trước bằng lời."

"I brought on death to my dear

ones

And they died one after another.

O my grief! Those graves

Were foretold by my word."

Anna Akhmatova And they died one after another.

O my grief! Those graves

Were foretold by my word."

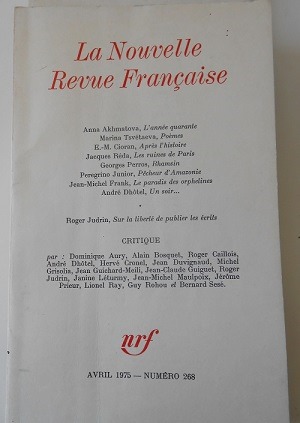

Khi người ta chôn một thời đại

Chẳng lời hát tang chế nào cất lên.

Để trang trí cho mộ phần kia

Chỉ thấy cúc gai với tầm ma

Và chỉ có bọn đào huyệt hối hả

Ra tay nhanh gọn vùi lấp nó.

Giữa niềm im lặng sâu không đáy

Khiến ta nghe được thời gian đi qua.

Rồi thời đại nổi lên như thi thể

Lênh đênh sông nước lúc xuân về.

Nhưng đứa con chẳng còn nhìn ra mẹ

Và thằng cháu quay lưng vì quá chán.

Nhựng các cái đầu càng cúi thấp hơn

Dưới đòn cân chậm chạp của vầng trăng .

Chẳng lời hát tang chế nào cất lên.

Để trang trí cho mộ phần kia

Chỉ thấy cúc gai với tầm ma

Và chỉ có bọn đào huyệt hối hả

Ra tay nhanh gọn vùi lấp nó.

Giữa niềm im lặng sâu không đáy

Khiến ta nghe được thời gian đi qua.

Rồi thời đại nổi lên như thi thể

Lênh đênh sông nước lúc xuân về.

Nhưng đứa con chẳng còn nhìn ra mẹ

Và thằng cháu quay lưng vì quá chán.

Nhựng các cái đầu càng cúi thấp hơn

Dưới đòn cân chậm chạp của vầng trăng .

Niềm im lặng ấy trị vì

Trên Paris đang chờ chết.

Trên Paris đang chờ chết.

Note: Thi sĩ Chân Phương,

có thể giỏi tiếng Tẩy, tiếng Anh, nhưng tiếng Việt, theo GCC, quá tệ.

“Qui meurt” làm sao mà là “đang chờ chết”?

Tệ lắm, thì cũng “đang chết”!

Tệ lắm, thì cũng “đang chết”!

Bài thơ làm năm 1940, tức

là cùng thời với Kinh Cầu.

Bèn lục tìm bản tiếng Anh,

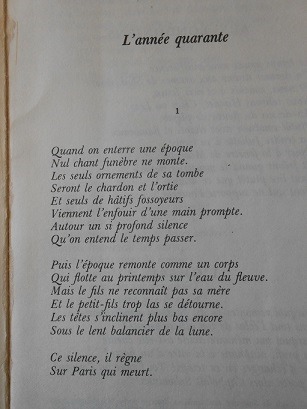

của Lyn Coffin:

IN 1940

1.

When they bury an epoch,

No psalms are read while the coffin settles,

The grave will be adorned with a rock,

With bristly thistles and nettles.

Only the gravediggers dig and fill,

Working with zest. Business to do!

And it's so still, my God, so still,

You can hear time passing by you.

And later, like a corpse, it will rise

Ride the river in spring like a leaf,-

But the son doesn't recognize

His mother, the grandson turns away in grief,

Bowed heads do not embarrass,

Like a pendulum goes the moon.

No psalms are read while the coffin settles,

The grave will be adorned with a rock,

With bristly thistles and nettles.

Only the gravediggers dig and fill,

Working with zest. Business to do!

And it's so still, my God, so still,

You can hear time passing by you.

And later, like a corpse, it will rise

Ride the river in spring like a leaf,-

But the son doesn't recognize

His mother, the grandson turns away in grief,

Bowed heads do not embarrass,

Like a pendulum goes the moon.

Well, this is the sort of silent

tune

That plays in fallen Paris.

That plays in fallen Paris.

2. To LONDONERS

The twenty-fourth drama by William

Shakespeare

Time is writing with a careless hand.

Since we partake of the feast of fear

We'd rather read Hamlet, Caesar, Lear,

By the river of lead where today we stand,

Or carry Juliet, sweet as a kiss,

To her grave, with songs and torches to lead,

Or tremble in darkness as in an abyss

With a hired killer Macbeth will need,-

Only . . . not this, not this, not this,

This we don't have the strength to read!

Time is writing with a careless hand.

Since we partake of the feast of fear

We'd rather read Hamlet, Caesar, Lear,

By the river of lead where today we stand,

Or carry Juliet, sweet as a kiss,

To her grave, with songs and torches to lead,

Or tremble in darkness as in an abyss

With a hired killer Macbeth will need,-

Only . . . not this, not this, not this,

This we don't have the strength to read!

5.

I warn you, that's the way things

are:

This is my final lifetime.

Not as a swallow, reed, or star,

Not as a bell to ring or chime,

Not as the water in a spring,

Not as a maple, branch or beam-

I won't alarm those who are living,

I won't appear in anyone's dream,

Unappeased and unforgiving.

This is my final lifetime.

Not as a swallow, reed, or star,

Not as a bell to ring or chime,

Not as the water in a spring,

Not as a maple, branch or beam-

I won't alarm those who are living,

I won't appear in anyone's dream,

Unappeased and unforgiving.

1940

Bản tiếng Anh, fallen Paris/Saigon, cho thấy, bị Nazi/VC lấy mẹ nó rồi, "đang chờ chết" cái con khỉ gì nữa!

IN 1940

1.

When they bury an epoch,

No psalms are read while the coffin settles,

The grave will be adorned with a rock,

With bristly thistles and nettles.

Only the gravediggers dig and fill,

Working with zest. Business to do!

And it's so still, my God, so still,

You can hear time passing by you.

And later, like a corpse, it will rise

Ride the river in spring like a leaf,-

But the son doesn't recognize

His mother, the grandson turns away in grief,

Bowed heads do not embarrass,

Like a pendulum goes the moon.

Well, this is the sort of silent tune

That plays in fallen Paris.

Khi họ chôn một thời kỳ

Không tụng ca được đọc khi hạ huyệt

Ngôi mộ sẽ được điểm trang bằng 1 cục đá.

Với cây kế tua tủa và tầm ma

Chỉ mấy đấng thợ, đào, và sau đó lấp, mồ.

Họ háo hức, hăm hở. Công việc mà!

Và thật câm lặng, Chúa ơi, thật câm lặng!

Bạn có thể nghe thời gian qua đi.

Và sau đó, như 1 cái thây ma, nó trỗi dậy

Bay trên mặt sông vào mùa xuân như 1 chiếc lá –

Nhưng ông con trai không nhận mẹ

Đứa cháu trai bỏ đi trong đau khổ

Những cái đầu cúi xuống đâu làm phiền ai

Như con lắc, mảnh trăng đong đưa

Đúng rồi, đúng điệu nhạc âm thầm đó

Dân Sài Gòn chơi, ngày mất Sài Gòn.

[Bản của GCC]

IN MEMORY OF MIKHAIL BULGAKOV

This poem comes to you instead of flowers,

Graveyard roses, or incense smoke;

You who even in the final hours

Showed marvelous disdain. You drank wine. You joked

Like no one else. As for the rest-

You suffocated in a walled-off square;

You yourself admitted the terrible guest,

And remained alone with her there.

Now you don't exist: no one says a thing

About your bitter and beautiful life;

Only my flutelike voice will sing

At this, your silent funeral feast.

It's unbelievable, to say the least,

That I, half-mad, mourning the past,

Smouldering on top of the slowest coal,

Having lost everything and forgotten them all,

Am fated to commemorate someone so strong,

Bright and steady to the final breath-

Was it yesterday we spoke? Has it been so long?-

Who hid the shuddering throes of death.

1940

Tưởng nhớ MIKHAIL BULGAKOV

Bài thơ này cho bạn, thay vì hoa

Hồng nghĩa trang, hay khói trước mồ

Bạn, những giờ cuối

Vẫn khinh khi lũ VC Nga thật là tuyệt cú mèo

Bạn uống hồng đào

Bạn chọc quê, kể chuyện hài, như chưa từng có ai làm được như thế

Về những gì còn lại –

Bạn nghẹt thở giữa bốn bức tường

Bạn, chính bạn đã chấp nhận vị khách khủng khiếp

Và một mình với nàng ở đó

Bây giờ bạn : Chẳng ai nói một điều gì

Về cuộc đời cay đắng và đẹp đẽ của bạn

Chỉ có giọng sáo diều của ta

Sẽ hát, ở đó,

Ở tang lễ im lìm của bạn

Thật là không thể tin nổi, chỉ nói thế thôi,

Rằng, ta, nửa khùng, nửa điên,

Tưởng niệm quá khứ

Âm ỉ trên đỉnh mớ than thấp, ở dưới đáy

Mất mọi thứ, và quên tất cả mọi thứ

Là người được số phận trao

Tưởng nhớ một người nào đó thật mãnh liệt,

Sáng ngời, và kiên định cho đến hơi thở chót –

Mà có phải là ngày hôm qua chúng ta nói tới? Sao lâu thế? –

Kẻ giấu những cơn giãy dụa của cái chết?

1940

Akhmatova

Epigram

Here the loveliest of young

women fight

for the honor of marrying the hangmen;

here the righteous are tortured at night

and the resolute worn down by hunger.

for the honor of marrying the hangmen;

here the righteous are tortured at night

and the resolute worn down by hunger.

(1928)

Robert Chandler

Anna Akhmatova

Robert Chandler

Anna Akhmatova

Note: Cái này, nhân ngày 8/3 tặng phu nhân

Cớm VC thì thật tuyệt

Thơ trào phúng

Đây là trận đấu đáng yêu nhất của những bà

nội trợ trẻ

Cho niềm vinh dự có ông chồng là đao phủ

Đây là kẻ trung trực bị tra tấn hàng đêm

Và sự kiên quyết tả tơi, bởi cơn đói

Cho niềm vinh dự có ông chồng là đao phủ

Đây là kẻ trung trực bị tra tấn hàng đêm

Và sự kiên quyết tả tơi, bởi cơn đói

In Memory of Sergey Yesenin

There are such easy ways

to leave this life,

to burn to an end

without pain or thought,

but a Russian poet

has no such luck.

A bullet is more likely

to show his winged soul

the way to Heaven;

or else the shaggy paw

of voiceless terror will squeeze

the life out of his heart

as if it were a sponge.

(1925)

Robert Chandler

Anna Akhmatova

Tưởng nhớ Sergey Yesenin

Có những cách dễ dàng như thế đấy

Để mà từ bỏ cõi đời này

Để cháy cạn láng

Không đau đớn, không nghĩ ngợi

Nhưng một nhà thơ Nga

Làm gì có cái may mắn như vậy

Một viên đạn, thường thì là như vậy

Để chỉ cho cái linh hồn của anh ta

Đường bay tới Thiên Đàng

Hay, có khi, thì là,

Cái móng, vuốt, tua tuả

Của một cơn ghê rợn lặng câm

Sẽ vắt kiệt trái tim anh ta

Như cái bọt biển

Music

for D. D. Sh.

Something miraculous burns brightly;

its facets form before my eyes.

And it alone can speak to me

when no one will stand by my side.

When my last friends had turned and gone

from where I lay, it remained close-

burst into blossom, into song,

like a first storm, like speaking flowers.

(1958)

Boris Dralyuk

Anna Akhmatova

to leave this life,

to burn to an end

without pain or thought,

but a Russian poet

has no such luck.

A bullet is more likely

to show his winged soul

the way to Heaven;

or else the shaggy paw

of voiceless terror will squeeze

the life out of his heart

as if it were a sponge.

(1925)

Robert Chandler

Anna Akhmatova

Tưởng nhớ Sergey Yesenin

Có những cách dễ dàng như thế đấy

Để mà từ bỏ cõi đời này

Để cháy cạn láng

Không đau đớn, không nghĩ ngợi

Nhưng một nhà thơ Nga

Làm gì có cái may mắn như vậy

Một viên đạn, thường thì là như vậy

Để chỉ cho cái linh hồn của anh ta

Đường bay tới Thiên Đàng

Hay, có khi, thì là,

Cái móng, vuốt, tua tuả

Của một cơn ghê rợn lặng câm

Sẽ vắt kiệt trái tim anh ta

Như cái bọt biển

Music

for D. D. Sh.

Something miraculous burns brightly;

its facets form before my eyes.

And it alone can speak to me

when no one will stand by my side.

When my last friends had turned and gone

from where I lay, it remained close-

burst into blossom, into song,

like a first storm, like speaking flowers.

(1958)

Boris Dralyuk

Anna Akhmatova

La Musique

à D. D. Ch.

Il y a en elle un miracle qui brûle.

Sous nos yeux, elle forme un cristal.

C'est elle-même qui me parle

Quand les autres ont peur de s'approcher.

Quand le dernier ami a détourné les yeux

Elle est restée avec moi dans ma tombe.

Elle a chanté comme le premier orage

Ou comme si les fleurs se mettaient toutes à parler.

Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966)

*

à D. D. Ch.

Il y a en elle un miracle qui brûle.

Sous nos yeux, elle forme un cristal.

C'est elle-même qui me parle

Quand les autres ont peur de s'approcher.

Quand le dernier ami a détourné les yeux

Elle est restée avec moi dans ma tombe.

Elle a chanté comme le premier orage

Ou comme si les fleurs se mettaient toutes à parler.

Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966)

*

Âm nhạc

Tặng Shostakovitch

Tặng Shostakovitch

Có ở trong nàng một phép lạ rực cháy

Dưới mắt chúng ta nàng tạo thành một khối pha lê

Chính là nàng đang nói với tôi

Trong khi những kẻ khác không dám tới gần.

Khi người bạn cuối cùng quay mặt

Nàng ở với tôi trong nấm mồ.

Nàng hát như cơn dông bão đầu tiên

Như thể tất cả những bông hoa cùng một lúc cùng cất tiếng.

Dưới mắt chúng ta nàng tạo thành một khối pha lê

Chính là nàng đang nói với tôi

Trong khi những kẻ khác không dám tới gần.

Khi người bạn cuối cùng quay mặt

Nàng ở với tôi trong nấm mồ.

Nàng hát như cơn dông bão đầu tiên

Như thể tất cả những bông hoa cùng một lúc cùng cất tiếng.

A chill

A chill on my helpless heart

Yet I am walking on air.

And I wear my left glove

On my right hand.

(from "The last date's song")

[Note: In “Strong Words”]

A chill on my helpless heart

Yet I am walking on air.

And I wear my left glove

On my right hand.

(from "The last date's song")

[Note: In “Strong Words”]

Song of a Last Encounter

I walked without dragging my feet

but felt heavy at heart and frightened;

and I pulled onto my left hand

the glove that belonged to the right one.

There seemed to be countless steps,

though I knew there were only three,

and an autumn voice from the maples

whispered, 'Die with me!

I have been undone by a fate

that is cheerless, flighty and cruel.'

I replied, 'So have I, my dearest -

let me die one death with you .. .'

The song of a last encounter:

I glanced up at a dark wall:

from the bedroom indifferent candles

glowed yellow ... And that was all.

(1911, Tsarskoye Selo)

Robert Chandler

Dense, impenetrable, Tatar,

drawn from God knows when,

it clings to every disaster,

itself a doom without end.

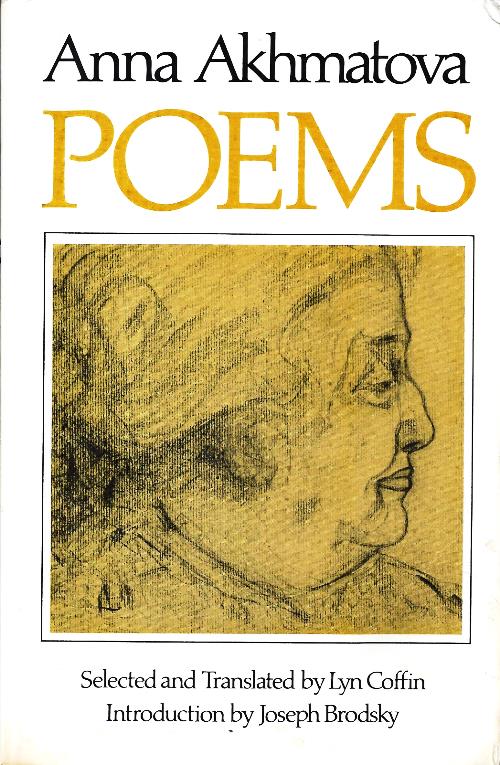

In 1910 she married Nikolay Gumilyov, whom she had first met seven years earlier and who had encouraged her in her writing. She was a key member of Gumilyov's Guild of Poets and of the Acmeist movement into which it developed. Though Akhmatova always remained loyal both to Acmeism in general and to Gumilyov's memory, their marriage seems to have been unhappy from the beginning. Another important early relationship was with the Italian artist Amadeo Modigliani, then young and unknown, with whom Akhmatova spent time in Paris in 1910 and 1911. Modigliani made at least sixteen drawings of her, though few have survived."

In 1918 Akhmatova and Gumilyov divorced. Akhmatova married the Assyriologist Vladimir Shileyko but separated from him after two years. During the 1920s and early 1930s she lived with the art critic Nikolay Punin; both Punin and Lev Gumilyov, Akhmatova's son by her first husband, were to serve several terms in the Gulag.

Between 1912 and 1921 Akhmatova published five books, to much acclaim; most of the poems are love lyrics, delicate and concise. In 1921, however, Gumilyov was shot for alleged participation in a monarchist conspiracy and it became difficult, eventually impossible, for Akhmatova to publish her own work. She wrote little between 1922 and 1940 and during most of her life she supported herself through translation; the poet Anatoly Naiman remembers her translating every day until lunchtime. Although she translated a few poems by Victor Hugo, Leopardi and other European poets, she worked mostly with languages she did not know, using cribs; she appears to have valued her translations of Serb epics and Korean classical poetry, though most of this work was no more than a necessary routine. She also wrote perceptive, scholarly articles about Pushkin.

Many of Akhmatova's friends emigrated after the Revolution, but Akhmatova made a conscious choice to share the destiny of her country. From the mid-1920S she embraced the role of witness to the tragedies of her age. She recalled later that by 1935 every time she went to see off a friend being sent into exile, she would find herself greeting countless other friends on the way to the railway station; there were always writers, scholars and artists leaving on the same train." As well as political epigrams, Akhmatova wrote two important long poems. The first, 'Requiem', is a response to the Great Terror of 1936-8. 'Poem without a Hero' (composed from 1940 to 1965) is longer and more cryptic; in it Akhmatova revisits her Bohemian past with mingled guilt, horror and pity. Neither poem was published in Russia until the late 1980s.

During the Second World War Akhmatova - along with Shostakovich and other Leningrad artists - was evacuated to Tashkent. In late 1945 and early 1946 the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, then attached to the British Embassy, visited her in her apartment. He impressed her deeply, and he appears several times in her later poetry as a mysterious 'guest from the future'. Soon after this visit, Akhmatova and the satirist Mikhail Zoshchenko were expelled from the Union of Soviet Writers. This was simply a part of the general post-war crackdown, but Akhmatova firmly believed it was a punishment for her meetings with Berlin.

Akhmatova's son Lev Gumilyov was rearrested in late 1949. Hoping to bring about his release, she wrote a poem in praise of Stalin. Her son, however, remained in the camps until 1956.

During her last years Akhmatova was a mentor to Joseph Brodsky and other younger poets. She was allowed to travel to Sicily to receive the Taormina Prize, then to England to receive an honorary doctorate from Oxford University. Her last public appearance was at the Bolshoy Theatre in October I965, during a celebration of the 700th anniversary of the birth of Dante. There she read her poem about Dante's exile and quoted other poems about Dante by Gumilyov and Mandelstam, neither of whom had yet been republished in the Soviet Union. In her notes for this talk she wrote, 'When ill-wishers mockingly ask what Gumilyov, Mandelstam and Akhmatova have in common, I want to reply "Love for Dante" .'

In November I965 Akhmatova suffered a heart attack, and she died in March I966. Her life during her last decades was recorded in detail by Lydia Chukovskaya in her Akhmatova Journals.

Osip Mandelstam said that Akhmatova 'brought into the Russian lyric all the huge complexity and psychological richness of the nineteenth-century Russian novel' Boris Pasternak wrote, 'All her descriptions, whether of a remote spot in a forest or of the noisy street life of the metropolis, are sustained by an uncommon flair for details."! Akhmatova herself noted in 1961, 'I listened to the Dragonfly Waltz from Shostakovich's Ballet Suite. It is a miracle. It seems that it is being danced by grace itself. Is it possible to do with the word what he does with sound?'

Akhmatova's poems are always graceful and the finest attain the intensity of prayers or spells. Almost all are in rhyme, though we have not always reproduced this. The second epilogue to 'Requiem' proved particularly difficult. All our attempts at reproducing its rhyming couplets seemed to compromise the dignified tone and almost architectural structure of the original.

but felt heavy at heart and frightened;

and I pulled onto my left hand

the glove that belonged to the right one.

There seemed to be countless steps,

though I knew there were only three,

and an autumn voice from the maples

whispered, 'Die with me!

I have been undone by a fate

that is cheerless, flighty and cruel.'

I replied, 'So have I, my dearest -

let me die one death with you .. .'

The song of a last encounter:

I glanced up at a dark wall:

from the bedroom indifferent candles

glowed yellow ... And that was all.

(1911, Tsarskoye Selo)

Robert Chandler

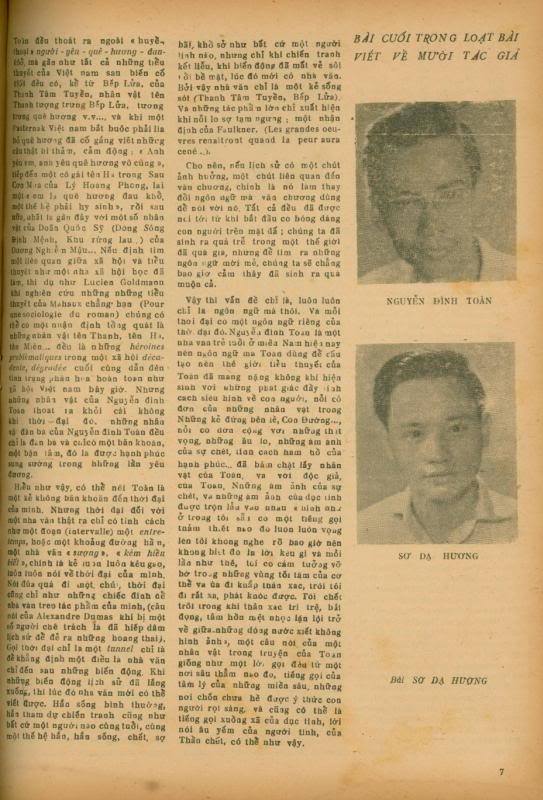

Anna Akhmatova, pseudonym of

Anna Gorenko (1889-1966)

Anna Andreyevna Gorenko's father was a maritime engineer. She was born

near Odessa, but her family moved to Tsarskoye Selo, near St Petersburg,

before she was one year old. She began publishing poetry in her late teens;

since her father considered this unrespectable, she adopted her grandmother's

Tatar surname - Akhmatova. In her last years she wrote this of her name:

Dense, impenetrable, Tatar,

drawn from God knows when,

it clings to every disaster,

itself a doom without end.

In 1910 she married Nikolay Gumilyov, whom she had first met seven years earlier and who had encouraged her in her writing. She was a key member of Gumilyov's Guild of Poets and of the Acmeist movement into which it developed. Though Akhmatova always remained loyal both to Acmeism in general and to Gumilyov's memory, their marriage seems to have been unhappy from the beginning. Another important early relationship was with the Italian artist Amadeo Modigliani, then young and unknown, with whom Akhmatova spent time in Paris in 1910 and 1911. Modigliani made at least sixteen drawings of her, though few have survived."

In 1918 Akhmatova and Gumilyov divorced. Akhmatova married the Assyriologist Vladimir Shileyko but separated from him after two years. During the 1920s and early 1930s she lived with the art critic Nikolay Punin; both Punin and Lev Gumilyov, Akhmatova's son by her first husband, were to serve several terms in the Gulag.

Between 1912 and 1921 Akhmatova published five books, to much acclaim; most of the poems are love lyrics, delicate and concise. In 1921, however, Gumilyov was shot for alleged participation in a monarchist conspiracy and it became difficult, eventually impossible, for Akhmatova to publish her own work. She wrote little between 1922 and 1940 and during most of her life she supported herself through translation; the poet Anatoly Naiman remembers her translating every day until lunchtime. Although she translated a few poems by Victor Hugo, Leopardi and other European poets, she worked mostly with languages she did not know, using cribs; she appears to have valued her translations of Serb epics and Korean classical poetry, though most of this work was no more than a necessary routine. She also wrote perceptive, scholarly articles about Pushkin.

Many of Akhmatova's friends emigrated after the Revolution, but Akhmatova made a conscious choice to share the destiny of her country. From the mid-1920S she embraced the role of witness to the tragedies of her age. She recalled later that by 1935 every time she went to see off a friend being sent into exile, she would find herself greeting countless other friends on the way to the railway station; there were always writers, scholars and artists leaving on the same train." As well as political epigrams, Akhmatova wrote two important long poems. The first, 'Requiem', is a response to the Great Terror of 1936-8. 'Poem without a Hero' (composed from 1940 to 1965) is longer and more cryptic; in it Akhmatova revisits her Bohemian past with mingled guilt, horror and pity. Neither poem was published in Russia until the late 1980s.

During the Second World War Akhmatova - along with Shostakovich and other Leningrad artists - was evacuated to Tashkent. In late 1945 and early 1946 the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, then attached to the British Embassy, visited her in her apartment. He impressed her deeply, and he appears several times in her later poetry as a mysterious 'guest from the future'. Soon after this visit, Akhmatova and the satirist Mikhail Zoshchenko were expelled from the Union of Soviet Writers. This was simply a part of the general post-war crackdown, but Akhmatova firmly believed it was a punishment for her meetings with Berlin.

Akhmatova's son Lev Gumilyov was rearrested in late 1949. Hoping to bring about his release, she wrote a poem in praise of Stalin. Her son, however, remained in the camps until 1956.

During her last years Akhmatova was a mentor to Joseph Brodsky and other younger poets. She was allowed to travel to Sicily to receive the Taormina Prize, then to England to receive an honorary doctorate from Oxford University. Her last public appearance was at the Bolshoy Theatre in October I965, during a celebration of the 700th anniversary of the birth of Dante. There she read her poem about Dante's exile and quoted other poems about Dante by Gumilyov and Mandelstam, neither of whom had yet been republished in the Soviet Union. In her notes for this talk she wrote, 'When ill-wishers mockingly ask what Gumilyov, Mandelstam and Akhmatova have in common, I want to reply "Love for Dante" .'

In November I965 Akhmatova suffered a heart attack, and she died in March I966. Her life during her last decades was recorded in detail by Lydia Chukovskaya in her Akhmatova Journals.

Osip Mandelstam said that Akhmatova 'brought into the Russian lyric all the huge complexity and psychological richness of the nineteenth-century Russian novel' Boris Pasternak wrote, 'All her descriptions, whether of a remote spot in a forest or of the noisy street life of the metropolis, are sustained by an uncommon flair for details."! Akhmatova herself noted in 1961, 'I listened to the Dragonfly Waltz from Shostakovich's Ballet Suite. It is a miracle. It seems that it is being danced by grace itself. Is it possible to do with the word what he does with sound?'

Akhmatova's poems are always graceful and the finest attain the intensity of prayers or spells. Almost all are in rhyme, though we have not always reproduced this. The second epilogue to 'Requiem' proved particularly difficult. All our attempts at reproducing its rhyming couplets seemed to compromise the dignified tone and almost architectural structure of the original.

Comments

Post a Comment