Nghĩa địa Do Thái ở Leningrad

Bài này đang Top. GCC đã dịch ra tiếng Mít. Post lại ở đây

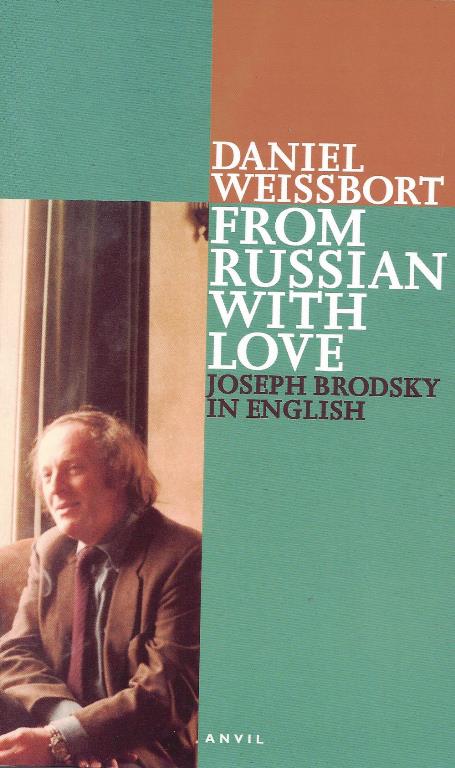

Bài thơ này có trong From Russia with Love, mà Tin Văn đang lai rai giới thiệu, và trong W.S. Merwin, Selected Translations.

Những lời lèm bèm về nó, là của tác giả cuốn From Russia with Love.

The Jewish cemetery near

Leningrad.

A crooked fence of rotten plywood.

And behind it, lying side by side,

lawyers, merchants, musicians, revolutionaries.

A crooked fence of rotten plywood.

And behind it, lying side by side,

lawyers, merchants, musicians, revolutionaries.

They sang for themselves.

They accumulated money for themselves.

They died for others.

They accumulated money for themselves.

They died for others.

But in the first place

they paid their taxes, and

respected the law,

and in this hopelessly material world,

they interpreted the Talmud, remaining idealists.

respected the law,

and in this hopelessly material world,

they interpreted the Talmud, remaining idealists.

Perhaps they saw more.

Perhaps they believed blindly.

But they taught their children to be patient

and to stick to things.

And they did not plant any seeds.

They never planted seeds.

They simply lay themselves down

in the cold earth, like grain.

And they fell asleep forever.

And after, they were covered with earth,

candles were lit for them,

and on the Day of Atonement

hungry old men with piping voices,

gasping with cold, wailed about peace.

Perhaps they believed blindly.

But they taught their children to be patient

and to stick to things.

And they did not plant any seeds.

They never planted seeds.

They simply lay themselves down

in the cold earth, like grain.

And they fell asleep forever.

And after, they were covered with earth,

candles were lit for them,

and on the Day of Atonement

hungry old men with piping voices,

gasping with cold, wailed about peace.

And they got it.

As dissolution of matter.

As dissolution of matter.

Remembering nothing.

Forgetting nothing.

Behind the crooked fence of rotting plywood,

four miles from the tramway terminus.

Forgetting nothing.

Behind the crooked fence of rotting plywood,

four miles from the tramway terminus.

Joseph Brodsky

Nghĩa địa Do Thái gần

Leningrad

Một hàng rào gỗ cong queo, mục nát

Và đằng sau nó, nằm, kế bên nhau

luật sư, thương nhân, nhạc sĩ, những nhà cách mạng

Một hàng rào gỗ cong queo, mục nát

Và đằng sau nó, nằm, kế bên nhau

luật sư, thương nhân, nhạc sĩ, những nhà cách mạng

Họ hát cho họ

Họ tích tụ tiền bạc cho họ

Họ chết cho những người khác

Nhưng trước hết, trên hết, họ đóng thuế

Và tuân theo luật pháp

Và trong cái thế giới trần tục, vật chất, vô hy vọng

Họ giải thích Kinh Talmud, và luôn giữ mình,

như những con người lý tưởng

Họ tích tụ tiền bạc cho họ

Họ chết cho những người khác

Nhưng trước hết, trên hết, họ đóng thuế

Và tuân theo luật pháp

Và trong cái thế giới trần tục, vật chất, vô hy vọng

Họ giải thích Kinh Talmud, và luôn giữ mình,

như những con người lý tưởng

Có thể họ nhìn nhiều hơn

Có thể, họ mù lòa tin tưởng

Nhưng họ dậy con cái hãy kiên nhẫn

Và bám sát vào sự vật

Và họ không gieo mầm

Họ không hề gieo mầm

Họ giản dị nằm xuống

Trên đất lạnh như hạt

Và chìm vào giấc ngủ đời đời

Và sau đó, đất phủ họ

Những cây đèn cầy vì họ được đốt lên

Và vào cái Ngày Chuộc Lỗi, Đền Tội

Những ông già đói khát, với giọng như tiếng sáo,

Thở hổn hển vì lạnh

Rên rỉ về hòa bường, hòa bường

Có thể, họ mù lòa tin tưởng

Nhưng họ dậy con cái hãy kiên nhẫn

Và bám sát vào sự vật

Và họ không gieo mầm

Họ không hề gieo mầm

Họ giản dị nằm xuống

Trên đất lạnh như hạt

Và chìm vào giấc ngủ đời đời

Và sau đó, đất phủ họ

Những cây đèn cầy vì họ được đốt lên

Và vào cái Ngày Chuộc Lỗi, Đền Tội

Những ông già đói khát, với giọng như tiếng sáo,

Thở hổn hển vì lạnh

Rên rỉ về hòa bường, hòa bường

Và họ có nó

Như phân huỷ vật chất

Như phân huỷ vật chất

Nhớ, chẳng nhớ gì

Quên, chẳng quên gì

Đằng sau hàng rào gỗ cong queo mục nát

Cách trạm xe điện cuối bốn dặm.

Quên, chẳng quên gì

Đằng sau hàng rào gỗ cong queo mục nát

Cách trạm xe điện cuối bốn dặm.

"Cemetery", as this poem

is called in the article, is uncharacteristic, not only on account of

the subject but prosodically as well. The first stanza is rhymed, but

thereafter the poem resolves itself into vers libre. I know of

no other poem like it in Joseph's published oeuvre. Indeed, were it not

that he never denied writing it, one might almost have thought it was

by someone else. In a sense, perhaps it was.

I never discussed it with Joseph, since we didn't talk about our Jewishness, or even Judaism as such, though I may have mentioned my own ambivalence. While it is sometimes suggested or claimed that Joseph had rejected Judaism, as far as I know he neither embraced it nor denied it. I think that his attitude did not really change. He was a Jew of the assimilated, Russified kind, a "bad Jew", as he put it, and not much interested in adopting or reclaiming the tradition; in short, he was no "refusenik". On the other hand, for instance, Anthony Rudolf, co-editor of the international anthology Voices Within the Ark: The Modern Jewish Poets (1980) tells me that when asked if he would be willing to be included in the book, Joseph replied that he wanted to be in it. And when, for instance, he was asked at a press conference in Stockholm, in December 1987, at the Nobel ceremonies, how he would describe himself, he answered: "I feel myself a Jew, although I never learnt Jewish traditions." He added, however: "But as for my own language, I undoubtedly regard myself as Russian."

Being a Jew, like being an exile, has certain advantages, in that (anywhere other than in Israel, perhaps New York, or wherever Jewish ghettos survive) it situates one on the margins, rather than at the centre of society. Jews tend to take on the colour of their surroundings. Jewish history, as a whole - and even "bad" Jews are heirs to that history - gives the individual Jew a claim, however tenuous, on a variety of cultural or linguistic territories. This is a source of strength, but also of weakness, in that he may feel that he truly belongs to none. Of course, Joseph did live in New York, but he was frequently on the road, in the States or abroad, and had another home in New England. Further- more, his exceptionally wide, international circle of friends and acquaintances far transcended the Jewish cultural world, assuming that there is such a thing.

I never discussed it with Joseph, since we didn't talk about our Jewishness, or even Judaism as such, though I may have mentioned my own ambivalence. While it is sometimes suggested or claimed that Joseph had rejected Judaism, as far as I know he neither embraced it nor denied it. I think that his attitude did not really change. He was a Jew of the assimilated, Russified kind, a "bad Jew", as he put it, and not much interested in adopting or reclaiming the tradition; in short, he was no "refusenik". On the other hand, for instance, Anthony Rudolf, co-editor of the international anthology Voices Within the Ark: The Modern Jewish Poets (1980) tells me that when asked if he would be willing to be included in the book, Joseph replied that he wanted to be in it. And when, for instance, he was asked at a press conference in Stockholm, in December 1987, at the Nobel ceremonies, how he would describe himself, he answered: "I feel myself a Jew, although I never learnt Jewish traditions." He added, however: "But as for my own language, I undoubtedly regard myself as Russian."

Being a Jew, like being an exile, has certain advantages, in that (anywhere other than in Israel, perhaps New York, or wherever Jewish ghettos survive) it situates one on the margins, rather than at the centre of society. Jews tend to take on the colour of their surroundings. Jewish history, as a whole - and even "bad" Jews are heirs to that history - gives the individual Jew a claim, however tenuous, on a variety of cultural or linguistic territories. This is a source of strength, but also of weakness, in that he may feel that he truly belongs to none. Of course, Joseph did live in New York, but he was frequently on the road, in the States or abroad, and had another home in New England. Further- more, his exceptionally wide, international circle of friends and acquaintances far transcended the Jewish cultural world, assuming that there is such a thing.

"Nghĩa địa" như bài thơ

được gọi, trong bài viết, thì chẳng hay ho gì, không chỉ ở cái giọng kể

lể, mà còn cả ở cái chất thơ xuôi của nó. Khổ đầu thì còn có vần điệu,

nhưng sau biến thành thơ tự do. Ngoài nó ra, không còn bài nào

như thế, trong số tác phẩm của Joseph... nhưng khi được 1 tay xb hỏi,

có cho nó vô 1 tuyển tập Những tiếng

nói ở bên trong [chiếc thuyền] Noé: Những nhà thơ Do Thái Hiện Đại,

do anh ta xb, hay là không [Anthony Rudolf, co-editor of the

international anthology Voices Within the Ark: The Modern Jewish

Poets (1980) tells me that when asked if he would be willing to be

included in the book], Brodsky nghiêm giọng phán, ta "muốn" có nó,

trong đó!

Hay, thí dụ, trong lần trả lời báo chí Tháng Chạp, 1987, ở Stockholm, khi tới đó lấy cái Nobel, “Tớ thấy tớ như 1 tên… Ngụy, dù chưa từng biết truyền thống Ngụy nó ra làm sao”, và nói thêm, “Về ngôn ngữ của riêng tớ, thì đúng là của 1 tên… Mít”!

Là 1 tên Ngụy, thì giống như 1 tên lưu vong, có tí lợi; nó đẩy tên đó ra bên lề, thay vì ở trung tâm xã hội. Lũ Ngụy có thói quen choàng cho chúng 1 màu của chung lũ chúng, ở loanh quanh chúng. Lịch sử Ngụy ban cho từng cá nhân Ngụy 1 thứ văn hóa, và đây là nguồn sức mạnh của chúng, nhưng vưỡn không làm sao giấu được nhược điểm, là ở bất cứ đâu, bất cứ lúc nào, nó cảm thấy chẳng ra cái chó gì cả, hắn đếch thuộc về ai, về đâu, đại khái thế!

Hay, thí dụ, trong lần trả lời báo chí Tháng Chạp, 1987, ở Stockholm, khi tới đó lấy cái Nobel, “Tớ thấy tớ như 1 tên… Ngụy, dù chưa từng biết truyền thống Ngụy nó ra làm sao”, và nói thêm, “Về ngôn ngữ của riêng tớ, thì đúng là của 1 tên… Mít”!

Là 1 tên Ngụy, thì giống như 1 tên lưu vong, có tí lợi; nó đẩy tên đó ra bên lề, thay vì ở trung tâm xã hội. Lũ Ngụy có thói quen choàng cho chúng 1 màu của chung lũ chúng, ở loanh quanh chúng. Lịch sử Ngụy ban cho từng cá nhân Ngụy 1 thứ văn hóa, và đây là nguồn sức mạnh của chúng, nhưng vưỡn không làm sao giấu được nhược điểm, là ở bất cứ đâu, bất cứ lúc nào, nó cảm thấy chẳng ra cái chó gì cả, hắn đếch thuộc về ai, về đâu, đại khái thế!

The Word That Causes Death’s Defeat

Cái từ đuổi Thần Chết chạy có cờ

Kinh Cầu đẻ ra từ một sự kiện, nỗi

đau cá nhân xé ruột xé gan, và cùng lúc, nó lại rất là của chung của cả

nước, một cách cực kỳ ghê rợn: cái sự bắt bớ khốn kiếp của nhà nước và

cái chết đe dọa người thân thương ruột thịt. Bởi thế mà nó có 1 kích

thước vừa rất đỗi riêng tư vừa rất ư mọi người, rất ư công chúng, một

bài thơ trữ tình và cùng lúc, sử thi. Nó là tác phẩm của ngôi thứ nhất,

thoát ra từ kinh nghiệm, cảm nhận cá nhân. Tuy nhiên, trong lúc chỉ là

1 cá nhân đau đớn rên rỉ như thế, thì nó lại là độc nhất: như sử thi,

bài thơ nói lên kinh nghiệm toàn quốc gia….

Đáp ứng, của Akhmatova,

khi Nikolai Gumuilyov, chồng bà, 35 tuổi, thi sĩ, nhà ngữ văn, trong

danh sách 61 người, bị xử bắn không cần bản án, vì tội âm mưu, phản

cách mạng, cho thấy quyết tâm của bà, vinh danh người chết và gìn giữ

hồi ức của họ giữa người sống, the determination to honor the dead, and

to preserve their memory among the living….

Trong 1 bài viết trên talawas, đại thi sĩ Kinh Bắc biện hộ cho cái sự ông ngồi nắn nón viết tự kiểm theo lệnh Tố Hữu, để được tha về nhà tiếp tục làm thơ, và tìm lá diêu bông, rằng, cái âm điệu thơ Kinh [quá] Bắc [Kít] của ông, buồn rầu, bi thương, đủ chửi bố Cách Mạng của VC rồi.

Trong 1 bài viết trên talawas, đại thi sĩ Kinh Bắc biện hộ cho cái sự ông ngồi nắn nón viết tự kiểm theo lệnh Tố Hữu, để được tha về nhà tiếp tục làm thơ, và tìm lá diêu bông, rằng, cái âm điệu thơ Kinh [quá] Bắc [Kít] của ông, buồn rầu, bi thương, đủ chửi bố Cách Mạng của VC rồi.

Theo sự hiểu biết cá nhân

của Gấu, thì chỉ hai nhà thơ, sống thật đời của mình, không 1 vết nhơ,

không khi nào phải “edit” cái phẩm hạnh của mình, là Brodsky và ông anh

nhà thơ của GCC.

Chẳng thế mà Milosz rất thèm 1 cuộc đời như của Brodsky, hay nói như 1 người dân bình thường Nga, tớ rất thèm có 1 cuộc đời riêng tư như của Brodsky, như trong bài viết của Tolstaya cho thấy.

Chẳng thế mà Milosz rất thèm 1 cuộc đời như của Brodsky, hay nói như 1 người dân bình thường Nga, tớ rất thèm có 1 cuộc đời riêng tư như của Brodsky, như trong bài viết của Tolstaya cho thấy.

Bảnh như Osip Mandelstam

mà cũng phải sống cuộc đời kép, trong thế giới khốn nạn đó. Để sống sót,

Mandelstam cũng đã từng phải làm thơ thổi Xì, như bà

vợ ông kể lại, và khi những người quen xúi bà, đừng bao giờ nhắc tới

nó, bà đã không làm như vậy:

Nadezhda Mandelstam

recalled how her husband Osip Mandelstam had done what was necessary to

survive:

To be sure, M. also, at

the very last moment, did what was required of him and wrote a hymn of

praise to Stalin, but the "Ode" did not achieve its purpose of saving

his life. It is possible, though, that without it I should not have

survived either. . . . By surviving I was able to save his poetry....

When we left Voronezh, M. asked Natasha to destroy the "Ode." Many

people now advise me not to speak of it at all, as thou it had never

existed. But I cannot agree to this, because the truth would then be

incomplete: leading a double life was an absolute fact of our age and

nobody was exempt. The only difference was that while others wrote

their odes in their apartments and country villas and were rewarded for

them, M wrote his with a rope around his neck. Akhmatova did the same,

as they drew-the noose tighter around the neck of her son. Who can

blame either her or M.

Roberta Reeder: Akhmatova, nhà thơ, nhà tiên tri

Roberta Reeder: Akhmatova, nhà thơ, nhà tiên tri

Trong khi lũ nhà văn nhà

thơ Liên Xô làm thơ ca ngợi Xì và được bổng lộc, thì M làm thơ ca ngợi

Xì với cái thòng lọng ở cổ, và bài thơ “Ode” đó cũng chẳng cứu được

mạng của ông. Người ta xúi tôi, đừng nhắc tới nó, nhưng tôi nghĩ không

được, vì như thế sự thực không đầy đủ: sống cuộc đời kép là sự thực

tuyệt đối của thời chúng ta.

Tuyệt.

Chỉ có hai nhà thơ sống sự

thực tuyệt đối của thời chúng ta, bằng cuộc đời “đơn” của họ, là

Brodsky và TTT!

Etkind relates how this

trial pitted two traditional foes against each other, the bureaucracy

and the intelligentsia. Brodsky represented Russian poetry.

"The

Jewish Cemetery in Leningrad"

VENICE. I

have not been there, but Joseph's Venice and even his Petersburg are

familiar

urban landscapes. Even if Joseph made little of it, perhaps his

Jewishness was

also in evidence. A sense of doom, of endurable disaster; of

self-depreciation

as well, alienation, although he managed to combine this with a kind of

assertiveness,

so that it never turned into Jewish selbsthass. In a way, the

Jewishness was a

given. Indeed, it was better not stated, since it could so easily lead

to

identification with victimhood. That may be why he never, so far as I

know,

re-printed the early "The Jewish Cemetery in Leningrad", another poem

that I translated, also because of its overtly Jewish content, unique

in his

work. The poem may not be written from the point of view of a victim,

but the

Jew as victim or scapegoat features in it. Oddly - or

not so oddly - this somewhat juvenile work was mentioned in an article

entitled

"A Literary Drone" in Vechernii Leningrad (Evening Leningrad) in

November 1963, a sort of prologue to the famous trial in February.

Casting

around for evidence in his writings of "Jewish nationalism", which

even so late in the history of the Soviet Union was still a heinous

sin, all his

accusers could come up with was this poem (friends of Joseph were also

named,

Vladimir Shveigolts, Anatoly Geikh- man, Leonid Aronzon, all typically

Jewish

names):

The Jewish

cemetery near Leningrad.

A crooked fence of rotten plywood.

And behind it, lying side by side,

lawyers, merchants, musicians, revolutionaries.

A crooked fence of rotten plywood.

And behind it, lying side by side,

lawyers, merchants, musicians, revolutionaries.

They sang

for themselves.

They accumulated money for themselves.

They died for others.

They accumulated money for themselves.

They died for others.

But in the

first place they paid their taxes, and

respected the law,

and in this hopelessly material world,

they interpreted the Talmud, remaining idealists.

respected the law,

and in this hopelessly material world,

they interpreted the Talmud, remaining idealists.

Perhaps they

saw more.

Perhaps they believed blindly.

But they taught their children to be patient

and to stick to things.

And they did not plant any seeds.

They never planted seeds.

They simply lay themselves down

in the cold earth, like grain.

And they fell asleep forever.

And after, they were covered with earth,

candles were lit for them,

and on the Day of Atonement

hungry old men with piping voices,

gasping with cold, wailed about peace.

Perhaps they believed blindly.

But they taught their children to be patient

and to stick to things.

And they did not plant any seeds.

They never planted seeds.

They simply lay themselves down

in the cold earth, like grain.

And they fell asleep forever.

And after, they were covered with earth,

candles were lit for them,

and on the Day of Atonement

hungry old men with piping voices,

gasping with cold, wailed about peace.

And they got

it.

As dissolution of matter.

As dissolution of matter.

Remembering

nothing.

Forgetting nothing.

Behind the crooked fence of rotting plywood,

four miles from the tramway terminus.

Forgetting nothing.

Behind the crooked fence of rotting plywood,

four miles from the tramway terminus.

"Cemetery",

as this poem is called in the article, is uncharacteristic, not only on

account

of the subject but prosodically as well. The first stanza is rhymed,

but

thereafter the poem resolves itself into vers

libre. I know of no other poem like it in Joseph's published

oeuvre.

Indeed, were it not that he never denied writing it, one might almost

have

thought it was by someone else. In a sense, perhaps it was.

I never discussed it with Joseph, since we didn't talk about our Jewishness, or even Judaism as such, though I may have mentioned my own ambivalence. While it is sometimes suggested or claimed that Joseph had rejected Judaism, as far as I know he neither embraced it nor denied it. I think that his attitude did not really change. He was a Jew of the assimilated, Russified kind, a "bad Jew", as he put it, and not much interested in adopting or reclaiming the tradition; in short, he was no "refusenik". On the other hand, for instance, Anthony Rudolf, co-editor of the international anthology Voices Within the Ark: The Modern Jewish Poets (1980) tells me that when asked if he would be willing to be included in the book, Joseph replied that he wanted to be in it. And when, for instance, he was asked at a press conference in Stockholm, in December 1987, at the Nobel ceremonies, how he would describe himself, he answered: "I feel myself a Jew, although I never learnt Jewish traditions." He added, however: "But as for my own language, I undoubtedly regard myself as Russian."

Being a Jew, like being an exile, has certain advantages, in that (anywhere other than in Israel, perhaps New York, or wherever Jewish ghettos survive) it situates one on the margins, rather than at the centre of society. Jews tend to take on the colour of their surroundings. Jewish history, as a whole - and even "bad" Jews are heirs to that history - gives the individual Jew a claim, however tenuous, on a variety of cultural or linguistic territories. This is a source of strength, but also of weakness, in that he may feel that he truly belongs to none. Of course, Joseph did live in New York, but he was frequently on the road, in the States or abroad, and had another home in New England. Further- more, his exceptionally wide, international circle of friends and acquaintances far transcended the Jewish cultural world, assuming that there is such a thing.

I never discussed it with Joseph, since we didn't talk about our Jewishness, or even Judaism as such, though I may have mentioned my own ambivalence. While it is sometimes suggested or claimed that Joseph had rejected Judaism, as far as I know he neither embraced it nor denied it. I think that his attitude did not really change. He was a Jew of the assimilated, Russified kind, a "bad Jew", as he put it, and not much interested in adopting or reclaiming the tradition; in short, he was no "refusenik". On the other hand, for instance, Anthony Rudolf, co-editor of the international anthology Voices Within the Ark: The Modern Jewish Poets (1980) tells me that when asked if he would be willing to be included in the book, Joseph replied that he wanted to be in it. And when, for instance, he was asked at a press conference in Stockholm, in December 1987, at the Nobel ceremonies, how he would describe himself, he answered: "I feel myself a Jew, although I never learnt Jewish traditions." He added, however: "But as for my own language, I undoubtedly regard myself as Russian."

Being a Jew, like being an exile, has certain advantages, in that (anywhere other than in Israel, perhaps New York, or wherever Jewish ghettos survive) it situates one on the margins, rather than at the centre of society. Jews tend to take on the colour of their surroundings. Jewish history, as a whole - and even "bad" Jews are heirs to that history - gives the individual Jew a claim, however tenuous, on a variety of cultural or linguistic territories. This is a source of strength, but also of weakness, in that he may feel that he truly belongs to none. Of course, Joseph did live in New York, but he was frequently on the road, in the States or abroad, and had another home in New England. Further- more, his exceptionally wide, international circle of friends and acquaintances far transcended the Jewish cultural world, assuming that there is such a thing.

“The Jewish

Cemetery in Leningrad" is not a good poem; it may even be a bad poem.

And

my reasons for translating it may not have been praiseworthy either.

The poem

seemed to me even then

somewhat jejune. Those interred in Leningrad's Jewish cemetery were cut

off

("sang for themselves "), landless ("they never planted seeds,

only themselves") and superstitious, imprisoned by tradition ("hungry

old men with piping voices"). Their hopes or beliefs were illusory: the

peace they prayed for came to them as "dissolution of matter". There

is no light; there is not

even a "nobody in a raincoat". And that's partly the trouble. The

poem is programmatic, its theme too large, given the means at the young

poet's

disposal. It is as if he simply did not know what to do with the

material. But

this in itself interested me, particularly in view of the extraordinary

sureness of his hand in all the other poems I'd looked at, even from

that early

period. It may have been the first of the few poems by Joseph that I

translated. For me it was a place of meeting with him, this having

nothing, I

suppose, to do with its literary worth.

When I asked Joseph if I might reprint my version, his response was: "Do what you like, Danny!" So, either he didn't give a damn, or he was disposed to indulge me. Perhaps both. Might he have responded differently, had I put it differently, viz. "Would you rather I didn't use it, Joseph?" After all, he had not said anything about his inclusion in the original Yevtushenko anthology, until Max Hayward gave him the opportunity to refuse, whereupon he did refuse!

When I asked Joseph if I might reprint my version, his response was: "Do what you like, Danny!" So, either he didn't give a damn, or he was disposed to indulge me. Perhaps both. Might he have responded differently, had I put it differently, viz. "Would you rather I didn't use it, Joseph?" After all, he had not said anything about his inclusion in the original Yevtushenko anthology, until Max Hayward gave him the opportunity to refuse, whereupon he did refuse!

Cuốn sách về

Brodsky này, như lời Bạt cho thấy, có cùng tuổi [hải ngoại] của Gấu,

1997, hay đúng

hơn, kém Gấu ba tuổi.

Gấu làm quen Brodsky thời gian này, nhân đọc Coetzee viết về những tiểu luận của ông, trên tờ NYRB; bài tưởng niệm khi ông mất, của Tolstaya...

Trong cuốn này, có nhắc tới bài viết, Gấu chôm, xen với những kỷ niệm về Joseph Huỳnh Văn, trong bài “Ai cho phép mi là thi sĩ”

Post ở đây, rảnh rang lèm bèm sau.

Thú nhất câu: "Hãy nhớ Gấu, và quên số mệnh cà chớn của Gấu"!

"Remember me, but ah! Forget my fate!"

Gấu làm quen Brodsky thời gian này, nhân đọc Coetzee viết về những tiểu luận của ông, trên tờ NYRB; bài tưởng niệm khi ông mất, của Tolstaya...

Trong cuốn này, có nhắc tới bài viết, Gấu chôm, xen với những kỷ niệm về Joseph Huỳnh Văn, trong bài “Ai cho phép mi là thi sĩ”

Post ở đây, rảnh rang lèm bèm sau.

Thú nhất câu: "Hãy nhớ Gấu, và quên số mệnh cà chớn của Gấu"!

"Remember me, but ah! Forget my fate!"

Postface

Monday, 19

May, 1997

WHEN I BEGAN this writing almost a year and a half ago, I intended ...

Well, I intended nothing. Rather, I was dealing, as best I could, with a persistent grief. And that led me to revisit our various times together. And that, in its turn, led me back to his writing, or one might say led me to it for the first time, because - as he put it: "all that is left of a man is a part of speech." I tried to separate the strands of our understandings and misunderstandings. The journal became as much a self-interrogation as an interrogation of our friendship. I found myself moving, quite confusingly, between private and public, between affinities, issues of friendship, and problems of translation. Of course, the journal is also about translation. It is a confession, too, although I have tried to limit that aspect of it, and not only because I know how much Joseph disliked confessionalism.

While writing, I have talked to others. I have been made aware of many different points of view, which not surprisingly are often conflicting. From these I have taken what seemed to illuminate my own perceptions and ignored, or left for others to explore or not explore, those which it seemed impertinent to work with. It has not been hard for me to steer clear of his "private life", since I was hardly privy to it. Quite a few of my remarks are speculative. But I have tried, in general, not to over- indulge myself in what at worst is simply fiction-making.

As I looked at one or two of Joseph's translations and, again, at many of his Russian poems, I was once more brought up against my ignorance, my over-dependency on intuition, my inability to pick up allusions. I also became aware - as I hardly was before - of the scale of the Russian tragedy, the truly heroic grandeur of the life, say, of Akhmatova. And Brodsky.

I have been listening to Purcell's Dido and Aeneas. And were I not convinced that it would come across as sentimental, I would re-name thjs manuscript "Remember Me". Dido cries: "Remember me, but ah! forget my fate!" In a letter to Brodsky probably 10 July I965; for an English translation, see Anna Akhmatova, My Half Century, Selected Prose, 1992) Akhmatova writes: "I'm at the hut. The well creaks, the ravens caw. I'm listening to the Purcell (Dido and Aeneas) that was brought on your recommendation. It is so powerful that it's impossible to talk about it." In an earlier letter (20 October I964) she had written: "Promise me one thing - that you will stay perfectly healthy, there's nothing on earth worse than hot-water bottles, shots, and high blood pressure - and the worse thing is that it's irreversible. And if you are healthy, golden paths, happiness, and that divine communion with nature, which so captivates all those who read your poetry,may await you." Alas, he was unable to heed her advice, but the reciprocal nature of their relationship, in spite of the age difference, is evident. One understands, he observed, walking beside Akhmatova, why Russia was sometimes ruled by empresses. But he did walk beside her.

Considered

by many to be the greatest Russian poet of his generation, Joseph

Brodsky

(1940-1996) received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1987. By this

time he

was a fluent writer and speaker of English - yet when exiled from the

Soviet

Union in 1972 (after serving 18 months of a five-year sentence in a

labour

camp) he was practically restricted to his native tongue. Brodsky, like

Nabokov, became that most rare and intriguing of writers - one who

mastered English

as a second creative language and re- invented himself in it.

Daniel

Weissbort was closely associated with Brodsky as friend and translator.

In

addition to being a fascinating biographical (and autobiographical)

study, From

Russian with Love provides detailed discussion of the problems of

Englishing

Brodsky's poems. Iris a telling contribution to translation studies and

a

searching meditation on the nature of language itself.

Daniel

Weissbort, born in I93S. co-founded with Ted Hughes the journal Modern

Poetry

in translation which he edited from 1965-1003. He directed the

Translation

Workshop at the University of Iowa for many years. His translations

from

Russian include the Selected Poems of Nikolai Zabolotsky and his most

recent

book of poems is Letters to Ted (Anvil. 2002).

He lives in London.

He lives in London.

Bài tưởng niệm

Brodsky của Tolstaya, mà Gấu chôm, viết về bạn không quí Joseph HV,

cũng có tí kỷ niệm thú vị.

NTV khi đó chưa về xứ Mít ở luôn, ghé nhà chơi, lấy tờ NYRB có bài viết về đọc, than, mi lọc ăn hết thịt, chỉ cho độc giả tí xương, ra ý, bài viết thì còn nhiều chi tiết quá hay, Gấu đếch dịch!

Không phải vậy.

Cái phần Gấu giữ lại, là tính để dành, cho 1 dịp khác.

Sau đó, Gấu đưa vô bài viết về Đỗ Long Vân, bạn của Joseph Huỳnh Văn, và đưa vô bài thơ gửi cho… Gấu Cái, như 1 lời tạ lỗi, cả 1 đời, mi đâu có dành cho ta dù chỉ nửa phút, mà chạy theo hết con này đến con kia!

NTV khi đó chưa về xứ Mít ở luôn, ghé nhà chơi, lấy tờ NYRB có bài viết về đọc, than, mi lọc ăn hết thịt, chỉ cho độc giả tí xương, ra ý, bài viết thì còn nhiều chi tiết quá hay, Gấu đếch dịch!

Không phải vậy.

Cái phần Gấu giữ lại, là tính để dành, cho 1 dịp khác.

Sau đó, Gấu đưa vô bài viết về Đỗ Long Vân, bạn của Joseph Huỳnh Văn, và đưa vô bài thơ gửi cho… Gấu Cái, như 1 lời tạ lỗi, cả 1 đời, mi đâu có dành cho ta dù chỉ nửa phút, mà chạy theo hết con này đến con kia!

Tatyana

Tolstaya, trong một bài tưởng niệm nhà thơ Joseph Brodsky, có nhắc đến

một cổ tục

của người dân Nga, khi trong nhà có người ra đi, họ lấy khăn phủ kín

những tấm

gương, sợ người thân còn nấn ná bịn rịn, sẽ đau lòng không còn nhìn

thấy bóng

mình ở trong đó; bà tự hỏi: làm sao phủ kín những con đuờng, những

sông, những

núi... nhà thơ vẫn thường soi bóng mình lên đó?

Chúng ta quá cách xa,

những con đường, những

sông, những núi, quá cách xa con người Đỗ Long Vân, khi ông còn cũng

như khi

ông đã mất. Qua một người quen, tôi được biết, những ngày sau 1975, ông

sống lặng

lẽ tại một căn hộ ở đường Hồ Biểu Chánh, đọc, phần lớn là khoa học giả

tưởng, dịch

bộ "Những Hệ Thống Mỹ Học" của Alain. Khi người bạn ngỏ ý mang đi, ra

ngoài này in, ông ngẫm nghĩ rồi lắc đầu: Thôi để cho PKT ở đây, lo việc

này

giùm tôi.... (2)

NQT

GCC có đọc

trên net, đâu đó, của 1 người, biết những ngày sau cùng, và cái chết

đau buồn của

DLV. Nó làm Gấu nhớ đến truyền thuyết về những con voi già, biết giờ

chết của mình,

bèn bò về nghĩa địa của loài voi…

Trong "Một Chủ Nhật Khác", TTT có nhắc tới giai thoại này, và cho biết thêm, cái tay kiếm ra Đà Lạt, và dựng nó thành 1 thành phố, là 1 trong những con voi, những cột trụ chống Trời, cho dân Mít.

Đâu có phải tự nhiên mà cuộc tình thần sầu chấm dứt cõi văn chương Ngụy thần sầu diễn ra ở Đà Lạt!

[Viết câu này là viết riêng cho Gấu, nhe!]

Trong "Một Chủ Nhật Khác", TTT có nhắc tới giai thoại này, và cho biết thêm, cái tay kiếm ra Đà Lạt, và dựng nó thành 1 thành phố, là 1 trong những con voi, những cột trụ chống Trời, cho dân Mít.

Đâu có phải tự nhiên mà cuộc tình thần sầu chấm dứt cõi văn chương Ngụy thần sầu diễn ra ở Đà Lạt!

[Viết câu này là viết riêng cho Gấu, nhe!]

Ui chao, bạn

DLV của GCC, lập lại y chang giai thoại, về tên Ngụy cuối cùng đó: Ta

đếch đi đâu,

cũng chẳng về nghĩa địa voi ở Đà Lạt, ta chọn 1 xó xỉnh nào của Sài

Gòn, để chết.

Hi vọng

Tặng em, như một lời tạ tội

Người

Nga, khi người thân vĩnh biệt

Thường phủ kín những tấm gương

Để người đi không đau lòng, hoảng hốt

Hồn còn đây, bóng đã không còn

Thường phủ kín những tấm gương

Để người đi không đau lòng, hoảng hốt

Hồn còn đây, bóng đã không còn

Người Việt

thường dặn dò

Hồn đừng quên

Con đường trở lại làm trẻ thơ

Mỗi lần qua sông, qua biển

Hồn đừng quên

Con đường trở lại làm trẻ thơ

Mỗi lần qua sông, qua biển

Anh mong có

em ở bên

Bởi vì chẳng bao giờ anh tìm thấy

Hình bóng anh

Ở trong em

Bởi vì chẳng bao giờ anh tìm thấy

Hình bóng anh

Ở trong em

Nhưng biết

đâu, vào giờ phút chót

Tuổi thơ của anh, của em

Nhập làm một

Tuổi thơ của anh, của em

Nhập làm một

Em chẳng

hằng mong

Đừng ai đi trước

Đừng ai đi trước

NQT

Xuống tiệm sách cũ, vồ

được cuốn này, quá tuyệt.

Post liền bài thơ “Nghĩa địa Văn Điển ở Hà Lội”. Bài này Gấu thấy rồi, tính giới thiệu rồi, nhưng nay có thêm 1 ấn bản nữa, kèm cả 1 chương sách về nó. Thú quá!

Còn vồ thêm được mấy cuốn nữa, cũng quá OK. Thơ của Bertold Brecht, thí dụ, quí vị độc giả TV, xin từ từ.... hà, hà!

Post liền bài thơ “Nghĩa địa Văn Điển ở Hà Lội”. Bài này Gấu thấy rồi, tính giới thiệu rồi, nhưng nay có thêm 1 ấn bản nữa, kèm cả 1 chương sách về nó. Thú quá!

Còn vồ thêm được mấy cuốn nữa, cũng quá OK. Thơ của Bertold Brecht, thí dụ, quí vị độc giả TV, xin từ từ.... hà, hà!

The Jewish cemetery near

Leningrad.

The Jewish cemetery near

Leningrad.

A crooked fence of rotten plywood.

And behind it, lying side by side,

lawyers, merchants, musicians, revolutionaries.

A crooked fence of rotten plywood.

And behind it, lying side by side,

lawyers, merchants, musicians, revolutionaries.

They sang for themselves.

They accumulated money for themselves.

They died for others.

But in the first place they paid their taxes, and

respected the law,

and in this hopelessly material world,

they interpreted the Talmud, remaining idealists.

They accumulated money for themselves.

They died for others.

But in the first place they paid their taxes, and

respected the law,

and in this hopelessly material world,

they interpreted the Talmud, remaining idealists.

Perhaps they saw more.

Perhaps they believed blindly.

But they taught their children to be patient

and to stick to things.

And they did not plant any seeds.

They never planted seeds.

They simply lay themselves down

in the cold earth, like grain.

And they fell asleep forever.

And after, they were covered with earth,

candles were lit for them,

and on the Day of Atonement

hungry old men with piping voices,

gasping with cold, wailed about peace.

Perhaps they believed blindly.

But they taught their children to be patient

and to stick to things.

And they did not plant any seeds.

They never planted seeds.

They simply lay themselves down

in the cold earth, like grain.

And they fell asleep forever.

And after, they were covered with earth,

candles were lit for them,

and on the Day of Atonement

hungry old men with piping voices,

gasping with cold, wailed about peace.

And they got it.

As dissolution of matter.

Remembering nothing.

Forgetting nothing.

Behind the crooked fence of rotting plywood,

four miles from the tramway terminus.

As dissolution of matter.

Remembering nothing.

Forgetting nothing.

Behind the crooked fence of rotting plywood,

four miles from the tramway terminus.

THE JEWISH CEMETERY

The Jewish Cemetery near

Leningrad:

a lame fence of rotten planks

and lying behind it side by side

lawyers, businessmen, musicians, revolutionaries.

a lame fence of rotten planks

and lying behind it side by side

lawyers, businessmen, musicians, revolutionaries.

They sang for themselves,

got rich "for themselves,

died for others.

But always paid their taxes first;

heeded the constabulary,

and in this inescapably material world

studied the Talmud,

remained idealists.

Maybe they saw something more,

maybe believed blindly.

In any case they taught their children

tolerance. But

obstinacy. They

sowed no wheat,

never sowed wheat,

simply lay down in the earth

like grain

and fell asleep forever.

Earth was heaped over them,

.andles were lit for them,

and on their day of the dead raw voices of famished

old men, the cold at their throats,

shrieked at them, “Eternal peace!”

Which they have found

in the disintegration of matter,

remembering nothing

forgetting nothing

got rich "for themselves,

died for others.

But always paid their taxes first;

heeded the constabulary,

and in this inescapably material world

studied the Talmud,

remained idealists.

Maybe they saw something more,

maybe believed blindly.

In any case they taught their children

tolerance. But

obstinacy. They

sowed no wheat,

never sowed wheat,

simply lay down in the earth

like grain

and fell asleep forever.

Earth was heaped over them,

.andles were lit for them,

and on their day of the dead raw voices of famished

old men, the cold at their throats,

shrieked at them, “Eternal peace!”

Which they have found

in the disintegration of matter,

remembering nothing

forgetting nothing

behind the lame fence of

rotten planks

four kilometers past the streetcar terminal.

four kilometers past the streetcar terminal.

1967, translated with

Wladimir Weidlé

W.S.

Merwin

Wladimir Weidlé

Comments

Post a Comment