Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo

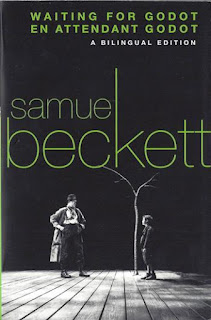

Waiting for Godot

in Sarajevo

Nothing to be done. / Nista ne moze da se uradi.

-opening line of "Waitingfor Godot"

1

I WENT TO Sarajevo in mid-July 1993 to stage a production of

"Waiting for Godot" not so much because I'd always wanted to direct

Beckett's play (although I had) as because it gave me a practical reason to

return to Sarajevo and stay for a month or more. I had spent two weeks there in

April, and had come to care intensely about the battered city and what it

stands for; some of its citizens had become friends. But I couldn't again be

just a witness: that is, meet and visit, tremble with fear, feel brave, feel

depressed, have heartbreaking conversations, grow ever more indignant, lose

weight. If I went back, it would be to pitch in and do something.

No longer can a writer consider

that the imperative task is to bring the news to the outside world. The news is

out. Many excellent foreign journalists (most of them in favor of intervention,

as I am) have been reporting the lies and the slaughter since the beginning of

the siege, while the decision of the western European powers and the United

States not to intervene remains firm, thereby giving the victory to Serb fascism.

I was not under the illusion that going to Sarajevo to direct a play would make

me useful in the way I could be if I were a doctor or a water systems engineer.

It would be a small contribution. But it was the only one of the three things I

do-write, make films, and direct in the theatre-which yields something that

would exist only in Sarajevo, that would be made and consumed there.

In April I'd met a young

Sarajevo-born theatre director, Haris Pasovic, who had left the city after he

finished school and made his considerable reputation working mainly in Serbia.

When the Serbs started the war in April I992, Pasovic went abroad, but in the

fall, while working on a spectacle called Sarajevo in Antwerp, he decided that

he could no longer remain in safe exile, and at the end of the year managed to

crawl back past UN patrols and under Serb gunfire into the freezing, besieged

city. Pasovic invited me to see his Grad (City), a collage, with music, of

declamations, partly drawn from texts by Constantine Cavafy, Zbigniew Herbert,

and Sylvia Plath, using a dozen actors; he'd put it together in eight days. Now

he was preparing a far more ambitious production, Euripides' Alcestis, after

which one of his students (Pasovic teaches at the still-functioning Academy of

Drama) would be directing Sophocles' Ajax. One day Pasovic asked me if I was

interested in coming back in a few months to direct a play.

More than interested, I told him.

Before I could add, "But let

me think for a while about what I might want to do," he went on,

"What play?" And bravado suggested to me in an instant what I might

not have seen had I taken longer to reflect: there was one obvious play for me

to direct. Beckett's play, written over forty years ago, seems written for, and

about, Sarajevo.

HAVING OFTEN BEEN ASKED since my return from Sarajevo if I

worked with professional actors, I've come to understand that many people find

it surprising that theatre goes on at all in the besieged city. In fact, of the

five theatres in Sarajevo before the war, two are still, sporadically, in use:

Chamber Theatre 55 (Kamerni Teater 55), where in April I'd seen a charmless

production of "Hair" as well as Pasovic's "Grad", and the

Youth Theatre (Pozoriste Mladih), where I decided to stage "Godot".

These are both small houses. The large house, closed since the beginning of the

war, is the National Theatre, which presented opera and the Sarajevo Ballet as

well as plays. In front of the handsome ochre building (only lightly damaged by

shelling), there is still a poster from early April 1992 announcing a new

production of Rigoletto, which never opened. Most of the singers and musicians

and ballet dancers left the city soon after the Serbs attacked, it being easier

for them to find work abroad, while many of the actors stayed, and want nothing

more than to work.

Another question I'm often asked

is: who goes to see a production of Waiting for Godot? Who indeed if not the

same people who would go to see Waiting for Godot if there were not a siege on?

Images of today's shattered city must make it hard to grasp that Sarajevo was

once an extremely lively and attractive provincial capital, with a cultural

life comparable to that of other middle-sized old European cities; that

includes an audience for theatre. As elsewhere in Central Europe, theatre in

Sarajevo was largely repertory: masterpieces from the past and the most admired

twentieth-century plays. Just as talented actors still live in Sarajevo, so do

members of this cultivated audience. The difference is that actors and

spectators alike can be murdered or maimed by a sniper's bullet or a mortar

shell on their way to and from the theatre; but then, that can happen to people

in Sarajevo in their living rooms, while they sleep in their bedrooms, when

they fetch something from their kitchens, as they go out their front doors.

BUT ISN’T THIS PLAY rather pessimistic? I've been asked.

Meaning, wasn't it depressing for an audience in Sarajevo; meaning, wasn't it

pretentious or insensitive to stage Godot there?-as if the representation of

despair were redundant when people really are in despair; as if what people

want to see in such a situation would be, say, The Odd Couple. The

condescending, philistine question makes me realize that those who ask it don't

understand at all what it's like in Sarajevo now, any more than they really

care about literature and theatre. It's not true that what everyone wants is

entertainment that offers them an escape from their own reality. In Sarajevo,

as anywhere else, there are more than a few people who feel strengthened and

consoled by having their sense of reality affirmed and transfigured by art.

This is not to say that people in Sarajevo don't miss being entertained. The

dramaturge of the National Theatre, who began sitting in on the rehearsals of

Godot after the first week, and who had studied at Columbia University, asked

me before I left to bring a few copies of Vogue and Vanity Fair when I return

later this month: she longed to be reminded of all the things that had gone out

of her life. Certainly, there are more Sarajevans who would rather see a

Harrison Ford movie or attend a Guns N Roses concert than watch Waiting for

Godot. That was true before the war, too. It is, if anything, a little less

true now.

And if one considers what plays

were produced in Sarajevo before the siege began-as opposed to the movies

shown, almost entirely the big Hollywood successes (the small cinematheque was

on the verge of closing just before the war for lack of an audience, I was

told)-there was nothing odd or gloomy

for the public in the choice of Waiting for Godot. The other productions

currently in rehearsal or performance are Alcestis (about the inevitability of

death and the meaning of sacrifice), Ajax (about a warrior's madness and

suicide), and In Agony, a play by the Croatian Miroslav Krleza, who is, with

the Bosnian Ivo Andric, one of the two internationally celebrated writers of

the first half of the century from the former Yugoslavia (the play's title

speaks for itself). Compared with these, Waiting for Godot may have been

the "lightest" entertainment of all.

INDEED, THE QUESTION IS not why there is any cultural

activity in Sarajevo now after seventeen months of siege, but why there isn't

more. Outside a boarded-up movie theatre next to the Chamber Theatre is a

sun-bleached poster for The Silence Of the Lambs with a diagonal strip across

it that says DANAS (today), which was April 6, 1992, the day moviegoing

stopped. Since the war began, all of the movie theatres in Sarajevo have

remained shut, even if not all have been severely damaged by shelling. A

building in which people gather so predictably would be too tempting a target

for the Serb guns; anyway, there is no electricity to run a projector. There

are no concerts, except for those given by a lone string quartet that rehearses

every morning and performs occasionally in a small room that also doubles as an

art gallery, seating forty. (It's in the same building on Marshal Tito Street

that houses the Chamber Theatre.) There is only one active space for painting

and photography, the Obala Gallery, whose exhibits sometimes stay up only one

day and never more than a week.

No one I talked with in Sarajevo

disputes the sparseness of cultural life in this city where, after all, between

300,000 and 400,000 inhabitants still live. The majority of the city's

intellectuals and creative people, including most of the faculty of the

University of Sarajevo, fled at the beginning of the war, before the city was

completely encircled. Besides, many Sarajevans are reluctant to leave their

apartments except when it is absolutely necessary, to collect water and the

rations distributed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

(UNHCR); though no one is safe anywhere, they have more to fear when they are

in the street. And beyond fear, there is depression-most Sarajevans are very depressed-which

produces lethargy, exhaustion, apathy.

Moreover, Belgrade was the

cultural capital of the former Yugoslavia, and I have the impression that in

Sarajevo the visual arts were derivative; that ballet, opera, and musical life

were routine. Only film and theatre were distinguished, so it is not surprising

that these continue under siege. A film production company, SAGA, makes both

documentary and fiction films, and there are the two functioning theatres.

IN FACT, THE AUDIENCE for theatre expects to see a play like

Waiting for Godot. What my production of Godot signifies to them,

apart from the fact that an eccentric American writer and part-time director

volunteered to work in the theatre as an expression of solidarity with the city

(a fact inflated by the local press and radio as evidence at the rest of the

world "does care," when I knew, to my indignation and shame, that I

represented nobody but myself), is that this is a great European play and that

they are members of European culture. For all their attachment to American

popular culture, as intense here as any-where else, it is the high culture of

Europe that represents for them their ideal, their passport to a European identity.

People had told me again and again on my earlier visit in April: We are part of

Europe. We are the people in the former Yugoslavia who stand for European

values-secularism, religious tolerance, and multi-ethnicity. How can the rest

of Europe let this happen to us? When I replied that Europe is and always has

been as much a place of barbarism as a place of civilization, they didn't want

to hear. Now no one would dispute such a statement.

CULTURE, SERIOUS CULTURE, is an expression of human

dignity-which is what people in Sarajevo feel they have lost, even when they

know themselves to be brave, or stoical, or angry. For they also know

themselves to be terminally weak: waiting, hoping, not wanting to hope, knowing

that they aren't going to be saved. They are humiliated by their

disappointment, by their fear, and by the indignities of daily life-for

instance, by having to spend a good part of each day seeing to it that their

toilets flush, so that their bathrooms don't become cesspools. That is how they

use most of the water they queue for in public spaces, at great risk to their

lives. Their sense of humiliation may be even greater than their fear.

Putting on a play means so much

to the local theatre professionals in Sarajevo because it allows them to be

normal, that is, to do what they did before the war; to be not just haulers of

water or passive recipients of humanitarian aid. Indeed, the lucky people in

Sarajevo are those who can carryon with their professional work. It is not a

question of money, since Sarajevo has only a black-market economy, whose

currency is German marks, and many people are living on their savings, which

were always in deutsche marks, or on remittances from abroad. (To get an idea

of the city's economy, consider that a skilled professional-say, a surgeon at

the city's main hospital or a television journalist-earns three deutsche marks

a month, while cigarettes, a local version of Marlboros, cost ten deutsche

marks a pack.) The actors and I, of course, were not on salary. Other theatre people

would sit in on rehearsals not just because they wanted to watch our work but

because they were glad to have, once again, a theatre to go to every day. Far

from it being frivolous to put on a play-this play or any other-it is a welcome

expression of normality. "Isn't putting on a play like fiddling while Rome

burns?" a journalist asked one of the actors. "Just asking a

provocative question," the journalist explained to me when I reproached

her, worried that the actor might have been offended. He was not. He didn't

know what she was talking about.

2

I STARTED AUDITIONING actors the day after I arrived, one

role already cast in my head. At a meeting with theatre people in April, I

couldn't have failed to notice a stout older woman wearing a large broad-brimmed

black hat who sat silently, imperiously, in a corner of the room. A few days

later when I saw her in Pasovic's Grad, I learned that she was the

senior actor of the pre-siege Sarajevo theatre, and when I decided to direct

Godot, I immediately thought of her as Pozzo. Pasovic concluded that I would

cast only women (he told me that an all-woman Godot had been done in Belgrade

some years ago). But that wasn't my intention. I wanted the casting to be

gender-blind, confident that this is one of the few plays where it makes sense,

since the characters are representative, even allegorical figures. If Everyman

(like the pronoun "he") really does stand for everybody-as women are

always being told-then Everyman doesn't have to be played by a man. I was not

making the statement that a woman can also be a tyrant-which Pasovic then

decided I meant by casting Ines Fancovic in the role- but rather that a woman

can play the role of a tyrant. In contrast, Admir ("Atko") Glarnocak,

the actor I cast as Lucky, a gaunt, lithe man of thirty whom I'd admired as

Death in Alcestis, fit perfectly the traditional conception of Pozzo's slave.

Three other roles were left:

Vladimir and Estragon, the pair of forlorn tramps, and Godot's messenger, a

small boy. It was troubling that there were more good actors available than

parts, since I knew how much it meant to the actors I auditioned to be in the

play. Three seemed particularly gifted: Velibor Topic, who was playing Death in

Alcestis; Izudin ("Izo") Bajrovic, who was Alcestis's Hercules; and

Nada Djurevska, who had the lead in the Krleza play.

Then it occurred to me I could

have three pairs of Vladimir and Estragon and put them all on the stage at

once. Velibor and Izo seemed likely to make the most powerful, fluent couple;

there was no reason not to use what Beckett envisaged, two men, at the center;

but they would be flanked on the left side of the stage by two women and on the

right by a woman and a man-three variations on the theme of the couple.

Since child actors were not available

and I dreaded using a nonprofessional, I decided to make the messenger an

adult: the boyish-looking Mirza Halilovic, a talented actor who happened to

speak the best English of anyone in the cast. Of the other eight actors, three

knew no English at all. It was a great help to have Mirza as interpreter, so I

could communicate with everybody at the same time.

BY THE SECOND DAY of rehearsal, I had begun to divide up and

apportion the text, like a musical score, among the three pairs of Vladimir and

Estragon. I had once before worked in a foreign language, when I directed

Pirandello's As You Desire Me at the Teatro Stabile in Turin. But I knew some

Italian, while my Serbo-Croatian (or "the mother tongue," as people

in Sarajevo call it, the words "Serbo-Croatian" being hard to utter

now) was limited when I arrived to "Please," "Hello,"

"Thank you," and "Not now." I had brought with me an

English-Serbo-Croatian phrase book, paperback copies of the play in English and

French, and an enlarged photocopy of the text into which I copied in pencil the

"Bosnian" translation, line by line, as soon as I received it. I also

copied the English and French line by line into the Bosnian script. In about

ten days I had managed to learn by heart the words of Beckett's play in the

language in which my actors were speaking it.

DID I HAVE a multi-ethnic cast? many people have asked me.

And if so, was there conflict or tension among the actors, or did they, as

someone here in New York put it to me, "get along with each other"?

But of course, I did-the

population of Sarajevo is so mixed, and intermarriage is so common, that it

would be hard to assemble any kind of group in which all three ethnic

identities were not represented. Eventually I learned that Velibor Topic

(Estragon I) has a Muslim mother and a Croat father, though he has a Serb first

name, while Ines Fancovic (Pozzo) had to be Croatian, since Ines is a Croat

name and she was born and grew up in the coastal town of Split and came to

Sarajevo thirty years ago. Both parents of Milijana Zirojevic (Estragon II) are

Serb, while Irena Mulamuhic (Estragon III) must have had at least a Muslim

father. I never learned the ethnic origins of all the actors. They knew them

and took them for granted because they are colleagues-they've acted in many

plays together-and friends.

Yes, of course they got along.

WHAT SUCH QUESTIONS show is that the questioner has bought

into the propaganda of the aggressors: that this war is caused by age- old

hatreds; that it is a civil war or a war of secession, with Milosevic trying to

save the union; that in crushing the Bosnians, whom Serb propaganda often

refers to as the Turks, the Serbs are saving Europe from Muslim fundamentalism.

Perhaps I should not have been surprised to be asked if I saw many women in

Sarajevo who are veiled, or who wear the chador; one can't underestimate the

extent to which the prevailing stereotypes about Muslims have shaped

"Western" reactions to the Serb aggression in Bosnia.

To invoke these stereotypes is

also to explain-this is another question I'm often asked-why other foreign

artists and writers who regard themselves as politically engaged haven't

volunteered to do something for Sarajevo. The danger can't be the only reason,

though that's what most people say is their reason for not considering a visit;

surely it was as dangerous to go to Barcelona in 1937 as it is to go to

Sarajevo in 1993. I suspect that the ultimate reason is a failure of

identification- enforced by the buzzword "Muslim." Even quite well

informed people in the United States and in Europe seem genuinely surprised

when I mention that, until the siege began, a middle-class Sarajevan was far

more likely to go to Vienna to the opera than to go down the street to a

mosque. I make this point not to suggest that the lives of non religious urban

Europeans are intrinsically more valuable than the lives of the devout of

Tehran or Baghdad or Damascus-every human life has an absolute value-but

because I wish it were better understood that it is precisely because Sarajevo

represents the secular, anti-tribal ideal that it has been targeted for

destruction.

In fact, the proportion of

religiously observant people in Sarajevo is about the same as it is among the

native-born in London or Paris or Berlin or Venice. In the prewar city, it was

no odder for a secular Muslim to marry a Serb or a Croat than for someone from

New York to marry someone from Massachusetts or California. In the year before

the Serb attack, sixty percent of the marriages in Sarajevo took place between

people from different religious backgrounds-the surest index of secularism.

Zdravko Grebo, Haris Pasovic,

Mirsad Purivatra, Izeta Gradevic, Amela Simic, Hasan Gluhic, Ademir Kenovic,

Zehra Kreho, Ferida Durakovic, and other friends of mine there of Muslim origin

are as much Muslim as I am Jewish-which is to say, hardly at all. Indeed, it

would be correct to say that I'm more Jewish than they are Muslim. My family

has been entirely secular for three generations, but I am, as far as I can

know, the descendant of an unbroken line of people under the same religious

discipline for at least two millennia, and have a complexion and cast of

features which identify me as the descendant of a branch of European (probably

originally Sephardic) Jewry, while the Sarajevans of Muslim origin come from

families that have been Muslim for at most five centuries (when Bosnia became a

province of the Ottoman Empire), and are physiologically identical with their

southern Slav neighbors, spouses, and compatriots, since they are in fact the

descendants of Christian southern Slavs.

What Muslim adherence had existed

throughout this century was already a diluted version of the moderate, Sunni

faith brought by the Turks, with nothing of what is now called fundamentalism.

When I asked friends who in their families are or were religiously observant,

they invariably said: my grandparents. If they were under thirty-five, they

usually said: my great-grandparents. Of the nine actors in Godot, the only one

with religious leanings was Nada, who is the disciple of an Indian guru; as her

farewell present she gave me a copy of the Penguin edition of The Teachings of

Shiva.

3

POZZO: There is no denying it is still day.

(They all look up at the sky.)

Good.

(They stop looking at the sky.)

OF COURSE, there were obstacles.

Not ethnic ones. Real ones.

To start with, we rehearsed in

the dark. The bare proscenium stage was lit usually by only three or four

candles, supplemented by the four flashlights I'd brought with me. When I asked

for additional candles, I was told there weren't any. Later I was told that

they were being saved for our performances. In fact, I never learned who doled

out the candles; they were simply in place on the floor when I arrived each morning

at the theatre, having walked through alleys and courtyards to reach the stage

door, the only usable entrance, at the rear of the freestanding modern

building. The theatre's facade, lobby, cloakroom, and bar had been wrecked by

shelling more than a year earlier and the debris still had not been cleared

away.

Actors in Sarajevo, Pasovic had

explained to me with comradely regret, expect to work only four hours a day.

"We have many bad habits here left over from the old socialist days."

But that was not my experience. After a bumpy start-during the first week

everyone seemed preoccupied with other performances and rehearsals, or

obligations at home-I could not have asked for actors more zealous, more eager.

The main obstacle, apart from the siege lighting, was the fatigue of the

malnourished actors, many of whom, before they arrived for rehearsal at ten,

had for several hours been queuing for water and then lugging heavy plastic

containers up eight or ten flights of stairs. Some of them had to walk two hours

to get to the theatre, and, of course, would have to follow the same dangerous

route at the end of the day.

The only actor who seemed to have

normal stamina was the oldest member of the cast, Ines Fancovic, who is

sixty-eight. Still large, she had lost more than sixty pounds since the

beginning of the siege, which may have accounted for her remarkable energy. The

other actors were visibly underweight and tired easily. Beckett's Lucky must

stand motionless through most of his long scene without ever setting down the

heavy bag he carries. Atko, who now weighs no more than one hundred pounds,

asked me to excuse him if he occasionally rested his empty suitcase on the

floor. Whenever I halted the run-through for a few minutes to change a movement

or a line reading, all the actors, with the exception of Ines, would instantly

lie down on the stage.

Another symptom of fatigue: they

were slower to memorize their lines than any actors I have ever worked with.

Ten days before the opening they still needed to consult their scripts, and

were not word- perfect until the day before the dress rehearsal. This might

have been less of a problem had it not been too dark for them to read the

scripts they held in their hands. An actor crossing the stage while saying a

line, who then forgot the next line, was obliged to make a detour to the

nearest candle and peer at his or her script. (A script was loose pages, since

binders and paper clips are virtually unobtainable in Sarajevo. The play had

been typed in Pasovic's office on a little manual typewriter whose ribbon had

been in use since the beginning of the siege. I was given the original and the

actors carbon copies, most of which would have been hard to read in any light.)

Not only could they not read

their scripts; unless standing face-to- face, they could barely see one

another. Lacking the normal peripheral vision that anybody has in daylight or

when there is electric light, they could not do something as simple as put on

or take off their bowler hats in unison. And they appeared to me for a long

time, to my despair, mostly as silhouettes. At the moment early in Act I when

Vladimir "smiles suddenly from ear to ear, keeps smiling, ceases as

suddenly"- in my version, three Vladimirs-I couldn't see a single one of those

false smiles from my stool some ten feet in front of them, my flashlight lying

across my scripts. Gradually, my night vision improved.

OF COURSE, it was not just fatigue that made the actors

slower to learn their lines and their movements and to be often inattentive and

forgetful. It was distraction, and fear. Each time we heard the noise of a

shell exploding, there was relief that the theatre had not been hit, but the

actors had to be wondering where it had landed. Only the youngest in my cast,

Velibor, and the oldest, Ines, lived alone. The others left wives and husbands,

parents and children at home when they came to the theatre each day, and

several of them lived very close to the front lines, near Grbavica, a part of

the city taken by the Serbs last year, or in Alipasino Polje, near the

Serb-held airport.

On July 30, at two o'clock in the

afternoon, Nada, who was often late during the first two weeks of rehearsal,

arrived with the news that at eleven that morning Zlajko Sparavolo, a

well-known older actor who specialized in Shakespearean roles, had been killed,

along with two neighbors, when a shell landed outside his front door. The

actors left the stage and went silently to an adjacent room. I followed them,

and the first to speak told me that this news was particularly upsetting to

everyone because, up till then, no actor had been killed. (I had heard earlier

about two actors who had each lost a leg in the shelling; and I knew Nermin

Tulic, the actor who lost both legs at the hip in the first months of the siege

and was now the administrative director of the Youth Theatre.) When I asked the

actors if they felt up to continuing the rehearsal, all but one, Izo, said yes.

But after working for another hour, some of the actors found they couldn't

continue. That was the only day that rehearsals stopped early.

THE SET I had designed-as minimally furnished, I thought, as

Beckett himself could have desired-had two levels. Pozzo and Lucky entered,

acted on, and exited from a rickety platform eight feet deep and four feet

high, running the whole length of upstage, with the tree toward the left; the

front of the platform was covered with the translucent polyurethane sheeting

that UNHCR brought in last winter to seal the shattered windows of Sarajevo.

The three couples stayed mostly on the stage floor, though sometimes one or

more of the Vladimirs and Estragons went to the upper stage. It took several

weeks of rehearsal to arrive at three distinct identities for them. The central

Vladimir and Estragon (120 and Velibor) were the classic buddy pair. After

several false starts, the two women (Nada and Milijana) turned into another

kind of couple in which affection and dependence are mixed with ex- asperation

and resentment: mother in her early forties and grown daughter. And Sejo and

Irena, who were also the oldest couple, played a quarrelsome, cranky husband

and wife, modeled on homeless people I'd seen in downtown Manhattan. But when

Lucky and Pozzo were onstage, the Vladimirs and Estragons could stand together,

becoming something of a Greek chorus as well as an audience to the show put on

by the terrifying master and slave.

Tripling the parts of Vladimir

and Estragon, which entailed new stage business, more intricate silences, had

the result of making the play a good deal longer than it usually is. I soon

realized that Act I would run at least ninety minutes. Act II would be shorter,

for my idea was to use only Izo and Velibor as Vladimir and Estragon. But even

with a stripped-down and speeded-up Act II, the play would be two and a half

hours long. And I could not envisage asking people to watch the play from the

Youth Theatre's auditorium, whose nine small chandeliers could come crashing

down if the building suffered a direct hit from a shell, or even if an adjacent

building were hit. Further, there was no way three hundred people in the

auditorium could see what was taking place on a deep proscenium stage lit only

by a few candles. But as many as a hundred people could be seated close to the

actors, at the front of the stage, on a tier of six rows of seats made from

wood planks. They would be hot, since it was high summer, and they would be

squeezed together; I knew that many more people would be lining up outside the

stage door for each performance than could be seated (tickets are free). How

could I ask the audience, which would have no lobby, bathroom, or water, to sit

so uncomfortably, without moving, for two and a half hours?

I concluded that I could not do

all of Waiting far Godot. But the very choices I had made about the staging

which made Act I as long as it was also meant that the staging could represent

the whole of Waiting for Godot, while using only the words of Act

1. For this may be the only work in dramatic literature in which Act I is

itself a complete play. The place and time of Act I are: "A country road.

A tree. Evening." (For Act II: "Next day. Same time. Same

place.") Although the time is "Evening," both acts show a

complete day, the day beginning with Vladimir and Estragon meeting again

(though in every sense except the sexual one a couple, they separate each

evening), and with Vladimir (the dominant one, the reasoner and

information-gatherer, who is better at fending off despair) inquiring where

Estragon has spent the night. They talk about waiting for Godot (whoever he may

be), straining to pass the time. Pozzo and Lucky arrive, stay for a while and

perform their "routines," for which Vladimir and Estragon are the

audience, then depart. After this there is a time of deflation and relief: they

are waiting again. Then the messenger arrives to tell them that they have

waited once more in vain.

Of course, there is a difference

between Act I and the replay of Act I which is Act II. Not only has one more

day gone by. Everything is worse. Lucky no longer can speak, Pozzo is now

pathetic and blind, Vladimir has given in to despair. Perhaps I felt that the

despair of Act I was enough for the Sarajevo audience, and I wanted to spare

them a second time when Godot does not arrive. Maybe I wanted to propose,

subliminally, that Act II might be different. For, precisely

as Waiting for

Godot was so apt an illustration of the feelings of

Sarajevans now- bereft, hungry, dejected, waiting for an arbitrary, alien power

to save

them or take them under its protection-it seemed apt, too,

to be staging Waiting for Godot, Act 1.

4

Alas, alas ... / Avaj, avaj ...

-from Lucky's monologue

PEOPLE IN SARAJEVO live harrowing

lives; this was a harrowing Godot. Ines was flamboyantly theatrical as

Pozzo, and Atko was the most heartrending Lucky I have ever seen. Atko, who had

ballet training and was a movement teacher at the Academy, quickly mastered the

postures and gestures of decrepitude, and responded inventively to my

suggestions for Lucky's dance of freedom. It took longer to work out Lucky's

monologue, which in every production of Godot I'd seen (including the one

Beckett himself directed in 1975 at the Schiller Theatre in Berlin) was, to my

taste, delivered too fast, as nonsense. I divided this speech into five parts,

and we discussed it line by line, as an argument, as a series of images and

sounds, as a lament, as a cry. I wanted Atko to deliver Beckett's aria about

divine apathy and indifference, about a heartless, petrifying world, as if it

made perfect sense. Which it does, especially in Sarajevo.

It has always seemed to me that

Waiting for Godot is a supremely realistic play, though it is generally acted

in something like a minimalist or vaudeville style. The Godot that the Sarajevo

actors were by inclination, temperament, previous theatre experience, and

present (atrocious) circumstances most able to perform, and the one I chose to

direct, was full of anguish, of immense sadness and, toward the end,

violence. That the messenger was a strapping adult meant

that when he announces the bad news, Vladimir and Estragon could express not

only disappointment but rage: manhandling him as they could never have done had

the role been played by a small child. (And there are six, not two, of them,

and only one of him.) After he escapes, they subside into a long, terrible

silence. It was a Chekhovian moment of absolute pathos, as at the end of The

Cherry Orchard, when the ancient butler Firs wakes up to find that he's

been left behind in the abandoned house.

IT FELT, during the mounting of Godot and this second

stay in Sarajevo, as if I were going through the replay of a familiar cycle:

some of the severest shelling of the city's center since the beginning of the

siege (on one day Sarajevo was hit by nearly four thousand shells); the raising

once more of the hopes of American intervention; the outwitting of Clinton (if

outwitting is not too strong a term to describe so weak a resolve) by the

pro-Serb United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) command, which claimed that

intervention would endanger UN troops; the steady increase in despair and

disbelief of the Sarajevans; a mock cease-fire (that means just a little

shelling and sniping, but since more people ventured out in the street, almost

as many were murdered and maimed each day); et cetera, et cetera.

The cast and I tried to avoid jokes about "waiting for

Clinton," but that was very much what we were doing in late July, when the

Serbs took, or seemed to take, Mount Igman, just above the airport. The capture

of Mount Igman would allow them to fire shells horizontally into the city, and

hope rose again that there would be American air strikes against the Serb gun

positions, or at least a lifting of the arms embargo. Although people were

afraid to hope, for fear of being disappointed, at the same time no one could

believe that Clinton would again speak of intervention and again do nothing. I

myself had succumbed to hope again when a journalist friend showed me a dim

satellite fax transmission of Senator Biden's eloquent speech in favor of

intervention, twelve single-spaced pages, which he had delivered on the floor

of the Senate on July 29. The Holiday Inn, the only still functioning hotel,

which is on the western side of the city's center, four blocks from the nearest

Serb snipers, was crowded with journalists waiting for the fall of Sarajevo or

the intervention; one of the hotel staff said the place hadn't been this full

since the 1984 Winter Olympics.

SOMETIMES I TGHOUT we were not waiting for Godot, or

Clinton. We were waiting for our props. There seemed no way to find Lucky's

suitcase and picnic basket, Pozzo's cigarette holder (to substitute for the

pipe) and whip. As for the carrot that Estragon munches slowly, rapturously:

until two days before we opened, we had to rehearse with three of the dry rolls

I scavenged each morning from the Holiday Inn dining room (rolls were the

breakfast offered) to feed the actors and assistants and the all-too-rare

stagehand. We could not find any rope for Pozzo until a week after we started

on the stage, and Ines got understandably cranky when, after three weeks of

rehearsal, she still did not have the right length of rope, a proper whip, a

cigarette holder, an atomizer. The bowler hats and the boots for the Estragons

materialized only in the last days of rehearsal. And the costumes- whose

designs I had suggested and the sketches of which I had approved in the first

week-did not come until the day before we opened.

Some of this was owing to the

scarcity of everything in Sarajevo. Some of it, I had to conclude, was typically

"southern" (or Balkan) manana-ism. ("You'll definitely have the

cigarette holder tomorrow," I was told every morning for three weeks.) But

some of the shortages were the result of rivalry between theatres. There had to

be props at the closed National Theatre. Why were they not available to us? I

discovered, shortly before the opening, that I was not just a visiting member

of the Sarajevo "theatre world," but that there were several theatre

clans in Sarajevo and that, being allied with Haris Pasovic's, I could not

count on the goodwill of the others. (It would work the other way around, too.

On one occasion, when precious help was offered me by another producer, who on

my last visit had become a friend, I was told by Pasovic, who was otherwise

reasonable and helpful: "I don't want you to take anything from that

person.")

Of course, this would be normal

behavior anywhere else. Why not in besieged Sarajevo? Theatre in prewar

Sarajevo must have had the same feuds, pettiness, and jealousy as in any other

European city. I think my assistants, as well as Ognjenka Finci, the set and

costume designer, and Pasovic himself, were anxious to shield me from the

knowledge that not everybody in Sarajevo was to be trusted. When I began to

catch on that some of our difficulties reflected a degree of hostility or even

sabotage, one of my assistants said to me sadly: "Now that you know us,

you won't want to come back anymore."

SARAJEVO IS NOT only a city that represents an ideal of

pluralism; it was regarded by many of its citizens as an ideal place: though

not important (not big enough, not rich enough), it was still the best place to

be, even if, being ambitious, you had to leave it to make a real career, as

people from San Francisco eventually take the plunge and go to Los Angeles or

New York. "You can't imagine what it used to be like here," Pasovic

said to me. "It was paradise." That kind of idealization produces a

very acute disillusionment, so that now almost all the people I know in

Sarajevo cannot stop lamenting the city's moral deterioration: the increasing

number of muggings and thefts, the gangsterism, the predatory black marketeers,

the banditry of some army units, the absence of civic cooperation. One would

think that they could forgive themselves, and their city. For seventeen months

it has been a shooting gallery. There is virtually no municipal government;

hence, debris from shelling doesn't get picked up, schooling isn't organized

for small children, et cetera, et cetera. A city under siege must, sooner or later,

become a city of rackets.

But most Sarajevans are pitiless

in their condemnation of conditions now, and of many "elements," as

they would call them with pained vagueness, in the city. "Anything good

that happens here is a miracle," one of my friends said to me. And

another: "This is a city of bad people." When an English

photojournalist made us the invaluable gift of nine candles, three were

immediately stolen. One day Mirza's lunch-a chunk of home-baked bread and a

pear-was taken from his knapsack while he was on the stage. It could not have

been one of the other actors. But it could have been anyone else, say, one of

the stagehands or any of the students from the Academy of Drama who wandered in

and out of the rehearsals. The discovery of this theft was very depressing to

us all.

Although many people want to

leave, and will leave when they can, a surprising number say that their lives

are not unbearable. "We can live this life forever," said one of my

friends from my April visit, Hrvoje Batinic, a local journalist. "I can

live this life a hundred years," a new friend, Zehra Kreho-the dramaturge

of the National Theatre-said to me one evening. (Both are in their late

thirties.) Sometimes I felt the same way.

Of course, it was different for

me. "I haven't taken a bath in sixteen months," a middle-aged matron

said to me. "Do you know how that feels?" I don't; I only know what

it's like not to take a bath for six weeks. I was elated, full of energy,

because of the challenge of the work I was doing, because of the valor and

enthusiasm of everyone I worked with-but I could not ever forget how hard it

has been for each of them, and how hopeless the future looks for their city.

What made my lesser hardships and the danger relatively easy to bear, apart

from the fact that I could leave and they couldn't, was that I was totally

concentrated on them and on Beckett's play.

5

UNTIL A WEEK before it opened, I did not think the play

would be very good. I feared that the choreography and emotional design I had

constructed for the two-level stage and the nine actors in five roles were too

complicated for them to master in so short a time; or simply that I had not

been as demanding as I should have been. Two of my assistants, as well as

Pasovic, told me that I was being too amicable, too "maternal," and

that I should throw a tantrum now and then and, in particular, threaten to

replace the actors who had not yet learned all their lines. But I went on,

hoping that it would be not too bad; then suddenly, in the last week, they

turned a corner, it all came together, and at our dress rehearsal it seemed to

me the production was, after all, affecting, continually interesting, well

made, and that this was an effort which did honor to Beckett's play.

I was also surprised by the amount

of attention from the international press that Godot was getting. I had told

few people that I was going back to Saravejo to direct Waiting for Godot,

intending perhaps to write something about it later. I forgot that I would be

living in a journalists' dormitory. The day after I arrived, I was fielding

requests in the Holiday Inn lobby and in the dining room for interviews; and

the next day; and the next. I said there was nothing to tell, that I was still

auditioning; then that the actors were simply reading the play aloud at a

table; then that we'd just begun on the stage, there was hardly any light,

there was nothing to see.

But when I mentioned to Pasovic

the journalists' requests and my desire to keep the actors free from such

distractions, I learned that he had scheduled a press conference for me and

that he wanted me to admit journalists to rehearsals, give interviews, and get

the maximum amount of publicity not just for the play but for an enterprise of

which I had not altogether taken in that I was a part: the Sarajevo

International Festival of Theatre and Film, directed by Haris Pasovic, whose

second production, following his Alcestis, was my Godot. When I apologized to

the actors for the interruptions to come, I found that they, too, wanted the

journalists to be there. All the friends I consulted in the city told me that

the story of the production would be "good for Sarajevo."

And so, I obediently changed my

policy of no interviews to giving access to anybody who wanted it. This was

easy, not only because it was what the actors and Pasovic wanted, but because I

never saw anything that was printed or televised (even the journalists at the

Holiday Inn never saw their stories until they left Sarajevo). I regretted,

though, that the rush of interviews in the first two weeks meant that most of

the stories were done before the actors had learned their lines, and my

conception of the play began to work.

The point is, of course, that any

cultural activity in Sarajevo is a sideshow for correspondents and journalists

who have come to cover a war. To protest the sincerity of one's motives

reinforces suspicion, if there is suspicion to begin with. The best thing is

not to speak at all, which was my original intention. To speak at all of what

one is doing seems-perhaps, whatever one's intentions, becomes-a form of self-

promotion. But this is just what the contemporary media culture expects. My

political opinions-I would go on about what I regard as the infamous role now

being played by UNPROFOR, railing against "the Serb-UN siege of

Sarajevo" -were invariably cut out. You want it to be about them, and it

turns out-in media land-to be about you.

If it were only a matter of my

own discomfort about some of the foreign coverage of my work in Sarajevo, none

of this would be worth mentioning. But it illustrates something of the way such

long-running stories as the one in Bosnia are transmitted and being reacted to.

Television, print, and

radio-journalism are an important part of this war. When, in April, I heard the

French intellectual André Glucksmann, on his twenty-four-hour trip to Sarajevo,

explain to the local journalists who attended his press conference that

"war is now a media vent," and "wars are won or lost on

TV," I thought to myself, Try telling that to all the people here who have

lost their arms and legs. But there is a sense in which Glucksmann's indecent

statement was on the mark. It's not that war has completely changed its nature,

and is only or principally a media event, but that the media's coverage is a

principal object of attention, and the very fact of media attention sometimes

becomes the main story.

An example. My best friend among

the journalists at the Holiday Inn, the BBC's admirable Alan Little, visited

one of the city's hospitals and was shown a semi-conscious five-year-old girl

with severe head in-

juries from a mortar shell that had killed her mother. The

doctor said she would die if she was not airlifted to a hospital where she

could be given a brain scan and sophisticated treatment. Moved by the child's plight,

Alan began to talk about her in his reports. For days nothing happened. Then

other journalists picked up the story, and the case of "Little Irma"

became the front-page story day after day in the British tabloids and virtually

the only Bosnia story on the TV news. John Major, eager to be seen as doing

something, sent a plane to take the girl to London.

Then came the backlash. Alan,

unaware at first that the story had become so big, then delighted because it

meant that the pressure would help to bring the child out, was dismayed by the

attacks on a “media circus" that was exploiting a child's suffering. It

was morally obscene, the critics said, to concentrate on one child when

thousands of children and adults, including many amputees and paraplegics, languish

in the understaffed, undersupplied hospitals of Sarajevo and are not allowed to

be transported out, thanks to the UN (but that is another story). That it was a

good thing to do-that to try to save the life of one child is better than doing

nothing at all-should have been obvious, and in fact others were brought out as

a result. But a story that needed to be told about the wretched hospitals of

Sarajevo degenerated into a controversy over what the press did.

THIS IS THE FIRST European genocide in our century to be tracked

by the world press and documented nightly on TV. There were no reporters in 19I5

sending daily stories to the world press from Armenia, and no foreign camera

crews in Dachau and Auschwitz. Until the Bosnian genocide, one might have

thought-this was indeed the conviction of many of the best reporters there,

like Roy Guttman of Newsday and John Burns of The New York Times-that if the

story could be gotten out, the world would do something. The coverage of the

genocide in Bosnia has ended that illusion.

Newspaper and radio reporting

and, above all, TV coverage have shown the war in Bosnia in extraordinary

detail, but in the absence of a will to intervene by those few people in the

world who make political and military decisions, the war becomes another remote

disaster; the people suffering and being murdered there become disaster

"victims." Suffering is visibly present, and can be seen in close-up;

and no doubt many people feel sympathy for the victims. What cannot be recorded

is an absence-the absence of any political will to end this suffering: more

exactly, the decision not to intervene in Bosnia, primarily Europe's responsibility,

which has its origins in the traditional pro-Serb slant of the Quai d'Orsay and

the British Foreign Office. It is being implemented by the UN occupation of

Sarajevo, which is largely a French operation.

I do not believe the standard

argument made by critics of television

that watching terrible events on the small screen distances

them as much as it makes them real. It is the continuing coverage of the war in

the absence of action to stop it that makes us mere spectators. Not television

but our politicians have made history come to seem like re-runs. We get tired

of watching the same show. If it seems unreal, it is because it's both so

appalling and apparently so unstoppable.

Even people in Sarajevo sometimes

say it seems to them unreal.They are in a state of shock, which does not diminish, which

takes theform of a rhetorical incredulity ("How could this

happen? I still can'tbelieve this is happening"). They are genuinely

astonished by the Serbs atrocities, and by the starkness and sheer unfamiliarity of

the lives theyare now obliged to lead. "We're living in the Middle

Ages," someonesaid to me. "This is science fiction," another

friend said.

People ask me if Sarajevo ever

seemed to me unreal while I was there. The truth is, since I've started going to

Sarajevo-this winter I hope to direct The Cherry Orchard with Nada as Madame

Ranevskyand Velibor as Lopakhin-it seems the most real place in the

world.

WAITING FOR GODOT OPENED with twelve candles on the

stage, on August 17. There were two performances that day, a Tuesday, one at 2:00

p.m. and the other at 4:00 p.m. In Sarajevo there are only matinees; hardly

anybody goes out after dark. Many people were turned away. During the first

performances I was tense with anxiety. By the third performance, I started to

be able to see the play as a spectator. It was time to stop worrying that Ines

would let the rope linking her and Atko sag while she devoured her papier-mache

chicken; that Sejo, the third Vladimir, would forget to keep shifting from foot

to foot just before he suddenly rushes off to pee. The play now belonged to the

actors, and I knew it was in good hands. And at the end of the 2:00 p.m. performance

on August 19, during the long tragic silence of the Vladimirs and Estragons

which follows the messenger's announcement that Mr. Godot isn't coming today,

but will surely come tomorrow, my eyes began to sting with tears. Velibor was

crying, too. No one in the audience made a sound. The only sounds were those

coming from outside the theatre: a UN armored personnel carrier thundering down

the street and the crack of sniper fire.

[1993]

Susan Sontag

Comments

Post a Comment