Solzhenitsyn by D.M. Thomas: A Century in his life

33

ANTIWORLDS

And let my works be seen and heard

By all who turn aside from me ....

-PUSHKIN, The Prophet

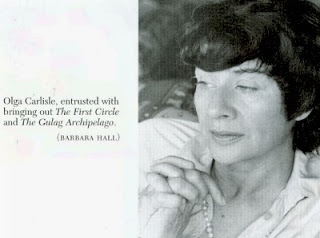

OLGA CARLISLE, A PAINTER AND JOURNALIST IN HER LATE THIRTIES, had an almost mystical love for the land of her forefathers. Born in Paris between the wars, married to an American, she had only in the past few years been allowed to visit Russia, but her family background had instantly opened the most distinguished doors. She had met Pasternak, Akhmatova, Nadezhda Mandelstam, Kornei Chukovsky and his daughter Lydia, the artist Neizvestny-and all had been pleased to welcome the granddaughter of a much-loved writer, Leonid Andreyev. Her distinguished antecedents did not stop with Andreyev; her maternal grandfather had been Victor Chernov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries and a member of Kerensky's provisional government in 1917. The Cheka had tried to hunt Chernov down, at Lenin's express order, but he had escaped.

On her fourth visit to Moscow, in April 1967, seeking material for a new collection of Russian poetry in translation, she felt still the enchantment, yet was also made uncomfortable by unexpected features. In the United States, the liberal intelligentsia to which she belonged took it for granted that the Soviet Union would gradually become more relaxed, despite recent setbacks; yet their counterparts in Moscow seemed gloomy and pessimistic. She found the dynamic young poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, resting between what he called "demanding, triumphal worldwide voyages," being given acupuncture at his dacha by a Chinaman. Looking like St. Sebastian, Yevtushenko told her in a low, depressed voice that freedom was again being crushed. His wife, who was knitting, pointed warningly toward the ceiling, and he dropped his voice still further. Another unpleasant paradox for an anti-Vietnam liberal in 1967: she was shocked to hear another dynamic young poet, Joseph Brodsky, express grim approval of President Johnson's escalation of America's involvement.

It was all very disturbing to a daughter of the Enlightenment.

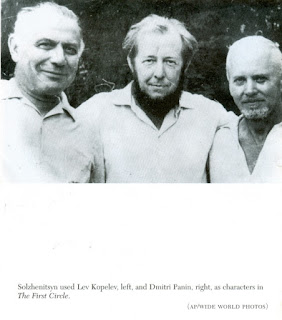

Everyone in Moscow was talking about Solzhenitsyn, everyone seemed to be in awe of him. Samizdat copies of a novel called “Cancer Ward” were everywhere, and Olga spent a sleepless night reading it. She knew he lived in Ryazan, and so did not expect to meet him; but then a friend, Lev Kopelev, phoned her at her hotel and hinted that she might meet Solzhenitsyn if she came to a small party. She came, and as she climbed one of those somber Russian staircases she saw him above her, tall, wearing a blue beret and carrying a small rucksack on his back. He darted down past her, averting his eyes, but when she rang the doorbell he was suddenly beside her, smiling. When they got inside, they were formally introduced by their hosts, and Olga was quickly under his spell. He was so healthy, so alive!

She couldn't help contrasting his vigor with the worn-out look of so many Moscow intellectuals, who stayed up too late drinking, smoking, and deciding the future of Russia .... His eyes watched her intently. He was in complete ascendency over the others present. His voice was rich and idiosyncratic, embodying old folk sayings and labor camp slang. It matched the vigor of his mind. She could scarcely follow the flow of conversation, since they seemed to be using a sort of intimate code; but she gathered that he thought Tvardovsky would not be able to get Cancer Ward published, despite his promises; he spoke scathingly of him, calling him a drunkard.' "I recognized you on the stairs," he said to the attractive French-Russian-American woman; "your photo is in Kornei Chukovsky's studio, which he's allowed me to work in. So I've been watched by you. You are less serious than in your photo." Later the same day, they met again at the home of Natalya Stolyarova, one of his helpers. At the end of the evening he escorted her back to her hotel. The streets were icy and he offered her his arm. She was aware of his strength, of the spring of his step. His face showed his age, but his walk was that of a much younger person. Relating to her how The First Circle had been "arrested," he showed her his rage by the tightening grip on her arm. The KGB was out to destroy him, he said; they would never forgive Ivan Denisovich. Everywhere, at every turning, there were huge banners in honor of the forthcoming fiftieth anniversary of the Revolution. He said to her, without pausing in his step, "I want you to see to the publication of “The First Circle” in the West."

As Olga went limp, he explained that she was to arrange for the translation and publication of the novel in such a way as to make as big a splash as possible. "Let it stun public opinion throughout the world; let the true nature of these scoundrels be known.”

They stopped. His sharp face faintly visible in the glow of a distant street- light, he released her arm and searched her face, wanting to know whether she had fully understood. She had, and felt a huge responsibility, and a sense of fatality. "I'll do my best."

"It's a big book-my life. Of course, it will have to be done in absolute secrecy. You can imagine what would happen to me if you were found out."

They walked on, past a large area that was only rubble. "Old Moscow is being destroyed," she murmured; he barely nodded, continuing to outline his strategy.

They neared the Hotel Leningradskaya. A vast portrait of jutting-jawed Lenin, opposite the hotel entrance with its huddle of police spies, stared at her. She and the writer shook hands, and he vanished, with the stealth of a commando, down a side street.

She slept little that night. She realized their meeting hadn't been an accident. He had been well served by Vadim, her father; and perhaps he had come to like the dark, brooding looks of Vadim' s daughter in the framed photograph at Chukovsky's dacha. He had learned that her husband, Henry Carlisle, was a former editor. She felt frightened, yet also exalted. She could do something worthwhile for Russia, something worthy of her grandfathers.

Flying home, she stopped off in Geneva to see her father. In his flat, which was like a little Russia, smoking Gauloise and drinking Italian coffee-so delicious after two months of the Russian kind-she told him she needed the microfilms. He paced the room, drawing on his cigarette, then said they must trust Solzhenitsyn's instincts, he was a former zek, and a very brave man. He brought the microfilms for her. She must be very careful; the slightest miscalculation on her part might kill him. She said she was only too aware of that.

At her home in Connecticut, she told her husband and waited to see how he would react. He listened gravely, then said it was an inviolable trust; it would be unthinkable to refuse; he would dedicate himself to it, with her, for as long as it took. It would be many months, they knew.

She read sections of The First Circle with the aid of a photographic enlarger and knew that this indeed was a landmark in twentieth-century Russian literature. She engaged a near-neighbor, Thomas Whitney, an expert on Russia, to prepare a rough translation. At a May party in gracious and affluent New England surroundings, she wanted to speak of the novel to her friend "Phil Roth," but bit her tongue; then she and Henry were being invited into the presence of Cass Canfield, head of the publishing house Harper & Row, in the study of his country house. He listened, and questioned; would they have world rights? Olga thought that was Solzhenitsyn's intention, but of course the author would have to confirm it. There had to be absolute secrecy, which meant an unusual vagueness; not even the lawyers should be confided in at this stage. Canfield seemed to understand.

Nearing seventy, though looking much younger, "he would suddenly shift his gaze and, with extreme intensity, settle all his attention on you .... " So far, not unlike an older Solzhenitsyn! "His long fleshy face was full of shrewdness; his blue eyes made you feel like a blossom in the path of, a humming-bird." It is not one of her most successful similes, yet its very fragility and awkwardness fits in with the sense she was beginning to have of "antiworlds" -the suffering of Russia in one world, and an American publisher and his shareholders in another." She would have to be the bridge, as so often in her divided life.

Thinking of that first Moscow encounter, she must have remembered the "most extraordinary" meeting of her first visit, with Pasternak; of how he had held her arm lightly-not fiercely as Alexander Isayevich had done- to help her across a little wooden bridge.4 And maybe, well-read as she was, seeing in her mind's eye the scene on the stairs when Solzhenitsyn ran down and then up, she recalled the moment in Doctor Zhivago when Yuri was confronted by his half brother, Yevgraf. ... "Footsteps sounded above him. Someone came slowly half-way down the stairs, stopped as if hesitating, then turned and ran up again to the first-floor landing .... " Yuri raises his head and sees the youth." Yevgraf becomes his savior yet also represents his death.

Olga Carlisle's initial sense of fatality would return, and grow stronger and stronger, threatening to overwhelm her.

Solzhenitsyn himself occupied antiworlds at this time. He seemed to be leading several different lives and achieving enough for a dozen different men. Michael Scammell likens him to a Scarlet Pimpernel; another analogy might be with the Pied Piper, leading his enemies to their doom, his followers, his "children," toward eternity. He was also a one-man army; his conversation with Olga Carlisle was full of "salvoes," "explosions," and "bombs."

He was turning into myth-even to himself: after describing how, in the winter of 1967, his second in Estonia, he had revised and retyped fifteen hundred pages of The Gulag Archipelago in seventy-three days, he exclaims, "It was not I who did it-mine was merely the hand that moved across the page!" He was becoming a Christ figure, and in relation to the women who served him-as to his mother long ago-there is a feeling of Noli me tangere. As Jesus to his disciples and to Mary Magdalene after his crucifixion, he would "disappear for a long time, only to reappear again as suddenly," Lydia Chukovskaya recalls." "Wherever Solzhenitsyn happened to dwell and wherever fate cast him, he never for a moment ceased to be the absolute master of his own life .... " He pursued his own routine, his own schedule of work, broken down not just into hours, but into minutes. He and Lydia met only on "neutral ground," such as kitchen or corridor, and there were never any long conversations. That would have been relaxation, idleness. "It was as if, at a certain moment ... he had sentenced himself to imprisonment in some strict regime camp and was now rigidly enforcing that regime. He was convict and guard rolled into one, and his own surveillance of himself was, perhaps, more relentless than that of the KGB. This heroic task called for ... an entire lifetime of toil with never a day off. And the main instrument of his labor was complete and well-fortified solitude."

Doubtless he treated her daughter Liusha in the same way.

Sometimes, Lydia wrote, he might leave a note, asking her if she would be free at nine; if so, they might listen to the radio together for twenty minutes. If they walked to the Peredelkino cemetery, he would be amazingly alert as to dangers on the path that might cause her to fall. He avoided the writers' village, except to go to the train station, preferring to walk among the pines on their land. When asked if he was not weary of walking back and forth, from one fence to the other, he replied, "No, I got used to it in the sharashka." She had the sense of a camp guard letting him out for two or three hours of exercise, whatever the weather, but doubted whether he

was freed from his labors even then.

But he insisted on being no trouble to anyone else, doing his own cooking and cleaning. Though he was early to bed and early to rise, if she whispered in saying good night to guests, at midnight, outside his room, fearing to disturb his sleep, he would say sternly the next morning, "I shall be unable to stay here if I find that my presence is going to inhibit you."

At meals he still worked, listening to the radio and jotting notes. He would ask sudden, peremptory questions of her sometimes, often about literature, would listen carefully to her answer, perhaps ask a supplementary question, and then leave the room.

Lydia Chukovskaya had absolutely no time for those who blamed Solzhenitsyn for having absolutely no time. They said, "He only ever has time for himself." For himself! Chukovskaya echoes ironically; when he had to raise a "colossal structure, this majestic monument on a communal grave beyond the Arctic Circle?" He has forced us, she writes, to experience the fate of hundreds, even thousands of individuals, in a form which is perhaps unique in world literature. She felt proud to have helped him maintain his ferocious timekeeping, as he called it. Vividly she relates how the vertical scar on his forehead could deepen, emphasizing the straightness of his features-nose, hair, forehead-until it seemed that the scar was listening to her across the table, so intense was his concentration. Once, when he was angry on her behalf, she saw not a face, but a knife. However, as the tension eased and they even joked, he started to laugh merrily, and then his face became "round, rustic, even, I would say, somewhat simple," the face of "a fitter or mechanic, not long out of the peasantry." The scar seemed to have

vanished, without trace.

These were rare moments of companionship. When he was at work writing, he was essentially alone, seeing only the phantoms of memory or imagined memory. Perhaps no writer has ever had such a gift of intense concentration, self-discipline, and ability to shut out everything and everyone.

In his second Estonian winter, he worked in a state of heavenly contentment. This year he could be more relaxed-if that is the word for such fiendish energy. Each day he went to bed exhausted at seven P.M., to wake up after one A.M. quite refreshed, and at once resume work. At nine A.M. he would stop, then move into a whole new day's work, finishing at six when he prepared a meal. When he became ill and was running a fever, he still chopped wood, stoked the stove, and did part of his writing standing up, with his back pressed against the hot tiles of the stove "in lieu of mustard plasters." His single goal, even should it cost him his life, was to finish the history of Russia's enslavement. Heli Susi, who came to the lonely farm-house occasionally with supplies, "said that she had the impression that I no longer belonged to anything or anyone in this world and that I seemed to be moving all by myself in an unknown direction.:" She would take away sections of the work for hiding. She taught German at Tallinn Conservatory, and had a son of fourteen, who prepared the microfilms of The Gulag Archipelago. Heli herself made many thoughtful suggestions from an aesthetic point of view.

Who can tell whether there lurks, behind the compliments to the daring and intelligent young woman-abandoned by her husband-who risked her freedom for his work's sake, an untold story? For her, caught up in the excitement of conspiracy, it would have been the most natural thing in the world to wish he were not quite so preoccupied when she came. For diversion, it seems, he chopped wood. And was, for ten weeks, a Stakhanovite writer working a double shift and no break for Sundays. Never had he been happier. All around, white snow, dark pines.

This was one antiworld, and the most important. "Silence, exile, cunning." An anti-Bolshevik conspirator; but also, the monk Pimen in Boris Godunov, writing his chronicle, bearing witness.

Once more the KGB had no idea where he was-or even that he was missing. There was no mention of an unexplained disappearance when the Secretariat of the Central Committee discussed him on 10 March 1967; but the tone-even without the Gulag-was ominous. Yuri Andropov, the KGB's head, said, "He has written certain things, like Feast of the Conquerors and Cancer Ward, that are anti-Soviet in nature. We should take decisive measures to deal with Solzhenitsyn." He was rearing his head, he thought he was a hero, commented Semichastny, reporting that he was reading his work in public and had given an interview to a Japanese newspaper. (He had been doing something far more threatening that that!) Shauro: "He has been very active lately. His place of residence is Ryazan, but he spends most of his time in Moscow .... " (If they but knew ...) "Incidentally, he gets help from well-known scientists such as Kapitsa and Sakharov." Demichev said he was a crazy writer who should be resolutely opposed. He was spreading slander against everything Russian, said Grishin; and Semichastny proposed that the first measure against him should be expulsion from the Writers' Union."

But nothing was done.

Upon his return in April 1967 from Estonia-bursting with health and energy, as Olga Carlisle witnessed-he plunged into a final revision of the second part of Cancer Ward, then went to see Tvardovsky to discuss the prospects of publication. They had not seen each other for eight months; the editor had been angry with him for allowing Cancer Ward to circulate in Moscow; Sanya had written to him asserting his light to be read. The reunion only served to deepen their rift. According to Solzhenitsyn's account: Tvardovsky said he had heard Cancer Ward had been published in the West. No, said Solzhenitsyn: just one chapter had been published abroad-by the Slovak Communist Party .... Tvardovsky was still deeply aggrieved: "You refuse to forgive the Soviet regime anything .... You have no genuine concern for the people! ... You hold nothing sacred! ... " And also: "I've been told you're always saying things against me .... "

"Against you? And you believed it?"

And reasonably so, on the evidence of Olga Carlisle: though, admittedly, she listened to him call Tvardovsky a drunkard a month after this rancorous meeting. Tvardovsky was feeling low, not having been re-elected to the Central Committee, and having lost two aides, the trusted Dementyev and Zaks. They had been dismissed from Navy Mir by the Central Committee, without explanation or consultation.

That April, Sanya made himself invisible again for a month at Rozhdestvo, his primitive dacha on the small river Istya. Despite its lack of conveniences and its tendency to flood, he and Natasha had grown to love the tranquil spot. During this spring, he wrote there an exuberant literary memoir, 150 pages long, of his battle with the Establishment. It would eventually become the opening section of The Oak and the Calf. His reason for writing this apologia was because he was not sure he would survive for long in freedom; he was about to write to the forthcoming Congress of the Writers' Union, and knew his letter would "go off like a bomb."

The danger of being blown up by it himself was also why he had "primed" Olga Carlisle for an even bigger explosion. He was throwing himself with that huge energy into his other antiworld of political controversy and polemics. This was to be his private Battle of Kursk. He gave his wife and other assistants their instructions. No fewer than 250 copies were typed of the two-thousand-word-long letter, each personally Signed; Liusha was mainly responsible for typing one hundred copies .... All 250 were posted from various Moscow districts, never more than two in the same box to outwit the postal censors. The recipients were carefully chosen: genuine writers (the majority), writers from non-Russian republics, and a few timeservers for confusion's sake, so as not to expose the decent people to KGB hostility.

Natasha tells us he played a recording of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony over and over as he composed his letter. It is a majestic plea for the Congress to discuss the "no longer tolerable oppression" of state censorship. "A survival of the Middle Ages, censorship has managed, Methuselah-like, to drag out its existence almost to the twenty-first century. Perishable, it attempts to arrogate to itself the prerogative of imperishable time- that of separating good books from bad.” There was no provision for censorship in the constitution and it was therefore illegal. Remorselessly he catalogs the writers, from Dostoyevsky to Pasternak, who were censored and abused, and then at some point published and celebrated. Was it not high time this absurd and immoral process was ended? Literature could not develop in the categories of "permitted" and "not permitted." "A literature," he wrote movingly, "that is not the breath of life for the society of its time, that dares not communicate its own pain and its own fears to society, that does not warn in time against threatening moral and social dangers does not deserve the name of literature; it is only a facade. Such a literature loses the confidence of its own people, and its published works are pulped instead of read.”

He followed this general statement by urging the Writers' Union to begin, at long last, to defend the rights of its members. It asked them to consider the wrongs done to him, Solzhenitsyn: the seizure of The First Circle and his entire archive; the slanderous accusations that he had surrendered to the enemy and served the Germans in the war; the unscrupulous dissemination of a play written when he was in the depths of despair, forgotten by society, and which he had long since abandoned.

He concluded: "I am of course confident that I shall fulfill my duty as a writer in all circumstances-from the grave even more successfully and incontrovertibly than in my lifetime. No one can bar the road to truth, and to advance its cause I am prepared to accept even death. But may it be that repeated lessons will finally teach us not to stay the writer's pen during his lifetime?

"This has never yet added luster to our history."

"What a nice, quiet congress it's been!" observed Mikhail Sholokhov, summing up at the end. The presumed author of Quiet Flows the Don was probably being sarcastic. Carefully selected, the assembly had indeed been soporifically well behaved, but Sholokhov well knew that outside the main Kremlin hall there was no topic of conversation other than Solzhenitsyn's bombshell of a letter. He had not been exaggerating, it was a bomb; and it burst with most stunning force in the West. The KGB was thrown into confusion as L'Unità, the official voice of the Communist Party of Italy, extolled the letter and criticized the Soviet Union's treatment of literature. The Politburo could only give floundering instructions to their ambassador in Rome to meet with Comrade Longo, leader of the Italian Communists, asking them not to rock the boat of Communism. The KGB produced a rather belated "biography" of the writer, inaccurate in only one small detail: it said his wife's father had died in the Civil War (the family's "official" version), whereas he had fled abroad. At a meeting in the Kremlin in July, Comrade Solomentsev said he had no doubt Solzhenitsyn should be de-bunked in the press, but would the Writers' Union be up to the task? There was a reminder of how negative had been the reaction to Sinyavsky/Daniel.

Solzhenitsyn, ignorant though he was of this Kremlin dithering, was overwhelmed by the response he was receiving, at home as well as abroad. About a hundred writers had replied to him agreeing that the issues of his letter should be openly discussed. Moreover, Tvardovsky was supporting him! Alexander Trifonovich was always taking him by surprise. It might still be possible, the editor said, for his journal to publish Cancer Ward. Solzhenitsyn found himself, with Tvardovsky, being offered the people's cigarettes and chocolate truffles at the Union offices.

Could Cancer Ward conceivably come out in the West, he was asked? Of course! he replied: it was always possible. There were so many copies floating around .... Consternation in the office; men coughing up their truffles. Please help to prevent that terrible thing, begged Tvardovsky, by letting Alexander Isayevich publish it here, in whatever journal he finds most to his taste ....

They saw no objection .... And thanked the novelist for coming!

But somewhere it was blocked.

During Natasha' s summer vacation they set off in their car for a holiday in what had been East Prussia. With them was another of those highly cultured couples with whom they got on well, Yefim and Ekaterina Edkind. They enjoyed camping at night along the route of General Samsonov's-and Solzhenitsyn's-advances. He was researching again for the work which he still regarded as his life's main task, a historical-literary study of the Revolution. He planned to begin writing it in the autumn.

When he started it, he found that scenes he had written as long ago as 1936 could be used still, with only the style needing to be polished.

There was almost, that summer, a reconciliation with one of the great friends of his youth, Kirill Simonyan. Simonyan had written to him following the letter to the Congress, and it was arranged that Sanya should call on him. When he did so, there was no answer to his ring on the bell. He waited an hour, then returned to leave a note. Opening the letter-flap, he saw Simonyan's legs, motionless, in the hall. Evidently, he had lost courage at the last moment. Sanya walked away, and they were never to meet.

The position with regard to Cancer Ward was that Novy Mir was ready to publish it but was waiting for permission. Solzhenitsyn wrote to the secretariat of the Writers' Union insisting that he would hold them responsible for the "senseless delay" of many months. He was invited, through Tvardovsky, to appear before them for a discussion. Tvardovsky told him there was hope, but the members had also been given A Feast of Conquerors to read, and there was much indignation about the play that expressed Syn1pathy for Vlasovite traitors. Tvardovsky himself, like Konstantin Simonov, was still refusing to read a work disowned by its author.

On 22 September, he prepared to confront the Union's secretariat in the building that had once fictionally housed the Rostov family in War and Peace. In the chair was to be the seventy-five-year-old Konstantin Fedin. It was Fedin who had wept over passages of Doctor Zhivago, and been Pasternak's friend and neighbor, but who cut him dead after the Nobel storm, and hid away during the funeral.

If Pasternak was Hamlet, Fedin and another neighbor of Pasternak's, Alexander Fadeyev, were Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Fadeyev, as Stalin's secretary of the Writers' Union, had liked Pasternak and possibly helped to preserve him; some thought the poet had had him in mind in creating Zhivago's helpful half-brother, Yevgraf. But he also signed away the lives of many writers. He became an alcoholic. In the wake of Khrushchev's sensational speech, Fadeyev had shot himself. Pasternak, after gazing down at the dead man in Moscow's Hall of Columns, said in a loud, clear voice, audible to everyone there, "Alexander Alexandrovich has rehabilitated himself." Then he bowed low before leaving. Fedin and Fadeyev .... This is Solzhenitsyn's wonderful description of the former. ... "On Fedin's face his every compromise, every betrayal, every base act, has superimposed its print in a dense crosshatching. (It was he who set the hounds on Pasternak, he who suggested the Sinyavsky trial.) Dorian Gray's sins all showed in the coarsening lines of his portrait. It was Fedin's lot to receive the marks on his face .... The face is bloodless under its patina of vice, a death's head smiling and nodding approval of the orators .... "

One can see Stalin's, Dzerzhinsky's, Beria's outraged ghosts: why do you expose yourselves to these insults? Just get this bastard into the Lubyanka and torture him to death ....

An hour before the meeting to discuss Cancer Ward, Sanya had a much more painful experience to go through.

Comments

Post a Comment