Sebald Tribute

Tribute

1

2

Tưởng

Niệm

Phát

biểu khi là ông Hàn

Sân

Trường Cũ

Sebald 1

Sebald's Mental Weather

Face à Sebald

Sebald Poetry

Notes on Sebald

Qua đất & Qua nước

Walser by Sebald

Ðặt chữ

Tuyển tập Thơ 1964-2001

Tác giả W.G. Sebald

Kể từ khi mất bất thình lình

do tai nạn xe hơi vào năm 2001, sự sùng bái W.G. Sebald ngày một tăng.

Ông gốc Ðức nhưng chọn Anh là nơi sinh sống. Ðược biết nhiều qua những tác

phẩm văn xuôi tinh tế, kết hợp cái thực với giả tưởng, đẩy tới mức giới hạn,

điều tiểu thuyết có thể làm được, ông được coi như là một trong những nhà

văn lỗi lạc nhất của thế hệ của ông. Ông còn là 1 nhà thơ.

Qua đất qua nước, một tuyển tập những

bài thơ chưa từng in trước đó, nếu có thể nói như vậy. Ðược dịch bởi Iain

Galbraith, Qua đất

qua nước, như cái tên cho thấy, phác ra một cuộc đời di động. Trải

dài 37 năm, tuyển tập bao gồm những bài thơ mà Mr Galbraith kiếm thấy tác

giả của nó viết vội, ở trong những hồ sơ, trên những mẩu giấy, trên tờ thực

đơn nhà hàng, chương trình của một buổi ca nhạc, kịch nghệ, hay những tờ giấy

có những tiêu đề của 1 nhà hàng, khách sạn. Chúng bật ra khi trên xe lửa,

hay ở một “ga không tên/ ở Wolfennbuttel”, Sebald kín đáo quan sát những

bạn đồng hành đi xe lửa bằng vé tháng, vé năm khi ông gợi ra những quang cảnh lùi về

phía sau ngược với con tàu.

Khác

văn xuôi của ông, có tính sử thi, gây chóng mặt, những bài thơ này thì cô

đọng, lơ thơ. Tuy nhiên chúng chứa đựng rất nhiều đề tài thường ám ảnh Sebald

suốt cuộc viết của ông. Nhà thơ trải qua những năm cuối đời ở Anh, làm việc

tại Ðại học Manchester và Ðông Anglia. Bận bịu với hồi nhớ, ao ước, và tính

ma quái của những sự vật, Sebald có thể gợi ra trong 1 bài thơ vẻ đẹp huyền

bí nhạt nhòa, 1 thứ Diễm Xưa, [thì cứ phán đại như vậy] của “thời quên lãng/của

núi non và đèn treo”, hay bước ngoặt của thế kỷ/ áo-thày tu và cây cung-vải

mỏng, trong khi ở 1 bài thơ khác, ông nói tới một “khu tháp/xấu xí”, hay

những “siêu thị hấp hối”. Sự chuyển đổi những thời khác nhau thì có vẻ ép

buộc, hay giả tạo, nhưng Sebald kiềm chế một chuyển động như thế bằng 1 cú

lướt nhẹ, bằng chờn vờn va chạm. Sự thực, cái sức mạnh dẫn dắt ở đằng sau

tác phẩm của ông, là 1 sự tìm kiếm, xục xạo quá khứ, tìm cái bị bỏ quên,

hay vờ đi, hoặc coi nhẹ: “Tôi muốn tìm hiểu/ những người đã chết thì ở đâu

đó, hay ở đó đâu”.

Như trong Austerlitz, giả tưởng văn xuôi, 2001, cuộc tìm kiếm người chết,

xoay quanh sự cố, ám ảnh cái viết của Sebald, và thường khiến ông viết, ở

[in] nơi chốn thứ nhất – Lò Thiêu. Trong một bài thơ ngắn, Ðâu đó, “Somewhere”,

thí dụ, dòng thơ mở đầu "behind, đằng sau, Turkenfeld", trở thành, với sự

giúp đỡ của Mr Galbraith, trong lời giới thiệu, đặc dị hơn nhiều, về 1 nơi

chốn khủng khiếp hơn rất nhiều, quá xa cái tít đơn giản mà nhà thơ đề nghị,

và, lẽ tất nhiên, vượt hẳn ra khỏi trí tưởng tượng của chúng ta:

Ngoài cái việc nó đã từng là 1 thành phố, khi chú bé Sebald, 8 tuổi, trên

đường đi tới Munich, vào năm 1952, Turkenfeld còn là 1 trong 94 tiểu Lò Thiêu,

của Ðại Lò Thiêu, Dachau, và còn là một ga xe lửa trên tuyến đường nổi tiếng

"Blutbahn" (Vệt Máu).

Giản dị, với 6 dòng thơ, vậy mà cái sức nặng lịch sử đè lên nó mới ghê rợn

làm sao!

[Mấy nhà thơ Mít, có ông đã từng đi tù VC, nhớ đọc bài thơ, và bài điểm,

trên tờ Người Kinh Tế, nhá!]

Tập thơ rộng rãi này cũng cho

chúng ta thấy một Sebald khác, bớt buồn bã đi một chút. Ông có thể nói tới

“nỗi đau/mà hồi ức hạnh phúc của tôi/ mang tới” nhưng cũng viết 1 cách vui

vẻ, trong hai bài thơ, nguyên tác viết bằng tiếng Anh, về một người đàn trẻ

ở New York mô tả, bà mới yêu thích làm sao, văn phòng của bà, có máy điều

hòa không khí, chống lại cái nóng mùa hè: “Ở đó/bà nói, tôi thì hạnh phúc

/như con hến mở ra/trên một cái giường nước đá lạnh”. Thơ của ông có thể

làm nhớ tới thứ thơ nặng [như đá] của Goethe, hay của Freud, nhưng nó cũng

lấy hứng khởi từ Anh em nhà Grimm, hay là từ những phim của Alain Renais.

Mr

Galbraith làm được 1 việc thật là tốt, khi chuyển dịch những chuyển đổi giọng

thơ, và nguồn ảnh hưởng. Tuy nhiên, đúng là 1 nhục nhã, khi tuyển tập thơ

này vờ nguyên tác tiếng Đức. Làm sao mà chúng ta không hiểu, thơ của Sebald

đâu có dễ dịch, nhưng chẳng lẽ bắt chước… Thầy Cuốc của xứ Mít giấu biệt

nguyên tác? Hơn thế nữa, làm sao mà chúng ta không quan tâm đến tính tha

thướt, hồn ma [the transitory and the ghostly], thật dễ dàng khi nghi ngờ,

chẳng có dịch giả nào mà tóm được thơ Sebald. Sebald, chính ông, cũng ngửi

ra điều này: “Nếu bạn biết rành mọi xó xỉnh/ của trái tim của tôi/ thì bạn

hơi 'vô tri’ đấy nhé”. Tuy nhiên, như những bài thơ cho thấy, tài năng của

ông, đó là làm cho kinh nghiệm về 1 thứ vô tri như thế, trở thành tuyệt vời.

“Ở đó / tôi thì hạnh phúc / như con hến mở ra / trên một cái giường nước đá lạnh”.

Thèm, nhỉ!Placing words

Across the Land and the Water:

Selected Poems 1964-2001. By W.G. Sebald, translated by lain Galbraith. Hamish

Hamilton; 240 pages; £14.99. To be published in America in April by Random

House; $25

SINCE W.G. Sebald's sudden death in 2001, the cult of the Britain-based

German writer has spread fast. Known for his exquisite prose works that,

in their combination of the real with the fictional, push at the limits of

what novels can be, he is considered one of the foremost German writers of

his generation. He was also a poet.

"Across the Land and the Water" brings together a selection of the poems

he never published in book form, if at all. Translated by lain Galbraith,

the volume sketches out a life on the move. Stretching over 37 years, the

volume includes poems that Mr Galbraith found jotted down in Sebald's archives

on scraps of paper, others written on menus, theatre programmes or headed

paper from hotels. They emerge on trains or at the "unmanned/station in Wolfennbuttel",

Sebald covertly observing fellow commuters as he evokes the differing landscapes

shuttling past.

Unlike his epic, vertiginous prose, these poems are often condensed and

sparse. And yet they contain many of the themes that would obsess Sebald

throughout his writing life. The poet spent his later years in Britain, working

at the Universities of Manchester and East Anglia. Preoccupied with memory,

desire and the ghostliness of objects, Sebald can evoke in one poem the faded

glamour of "a forgotten era/of fountains and chandeliers" or a "turn-of-the-century/frock-coat

and taffeta bow" while in another he will speak of an "ugly/ tower block"

or "moribund supermarkets". This shift between differing eras could seem

forced or artificial. And yet Sebald manages such movement with a lightness

of touch. Indeed, the driving force behind his work is a search for the past,

for the forgotten or overlooked: "I wish to inquire/Into the whereabouts

of the dead."

As in "Austerlitz", his 2001 work of prose fiction, this search for the dead

circles around the occurrence that haunts Sebald's writing, and which often

prompts him to write in the first place-the Holocaust. In one short poem,

"Somewhere", for example, the opening line "behind Turkenfeld" becomes, with

the help of Mr Galbraith's introduction, a far more specific and terrifying

location than Sebald's title suggests. Along with being a town the then eight-year-old

Sebald would frequently pass on his way to Munich in 1952, Turkennfeld was

one of the 94 sub-camps of Dachau, and a train station on the notorious "Blutbahn"

(blood track). Even in a seemingly simple six-line poem, the sudden weight

of historical events can be felt.

This broad collection also shows Sebald's writing in a less melancholy light.

He may speak of "the pain my happy/ memories bring" but can also, in one

of the two poems originally written in English, write playfully of a young

woman in New York describing how much she loves the air-conditioning in her

office as opposed to the summer heat: "There,/she said, I am/ happy like an/opened

up oyster/on a bed of ice." His poetry can refer to such heavyweights as Goethe

or Freud, but it also takes inspiration from the Brothers Grimm or the films

of Alain Resnais.

Mr Galbraith does a good job translating these shifting tones and influences.

However, it is a shame that this volume does not include Sebald's original

poems in the German. Concerned with the transitory or the ghostly, it is

easy to suspect that no one translation could pin Sebald down. Sebald himself

seemed aware of this: "If you knew every cranny/of my heart/you would yet

be ignorant." And yet as these poems show, his talent lay in making the experience

of such ignorance delightful. +

The Economist, Nov 19-25 2011

Ðặt chữ

Qua Ðất Ðai Qua Sông Nước

Tuyển tập Thơ 1964-2001

Tác giả W.G. Sebald

Ông gốc Ðức nhưng chọn Anh là nơi sinh sống. Ðược biết nhiều qua những tác phẩm văn xuôi tinh tế, kết hợp cái thực với giả tưởng, đẩy tới mức giới hạn, điều tiểu thuyết có thể làm được, ông được coi như là một trong những nhà văn lỗi lạc nhất của thế hệ của ông. Ông còn là 1 nhà thơ.

W.G. Sebald: The Remorse of the Heart.

On Memory and Cruelty in the Work of Peter Weiss

Weiss tham dự

tòa án xử vụ Lò Thiêu ở Frankfurt. Có thể là do ông vẫn còn hy vọng, một niềm

hy vọng chẳng hề tàn lụi, rằng, “mọi tổn thương thì có cái phần

tương đương của nó, ở đâu đó, và có thể thực sự được đền bù, bù trừ,

bồi hoàn, ngay cả, sự bồi hoàn này thông qua nỗi đau của bất cứ kẻ nào gây

ra sự tổn thương”. Tư tưởng này Nietzsche nghĩ, nó là cơ sở của cảm quan

của chúng ta về công lý, và nó, như ông nói, “nằm trong liên hệ có tính khế

ước, giữa chủ nợ và con nợ, và nó cũng cổ xưa, lâu đời như là quan niệm về

luật pháp, chính nó”

W.G. Sebald: Sự hối hận của con tim.

Moi, je traine le fardeau de la

faute collective, dis-je, pas eux.

Jean Améry viết, trong Vượt quá tội ác và hình phạt, Par-delà

le crime et le châtiment.

Gấu cũng có thể nói như thế:

Ta mang cái gánh nặng của Cái Ác Bắc Kít, đâu phải lũ

Bắc Kít?

Carole Angier [The

Jewish Quarterly, Winter 1996-7]:

… Và chúng ta nói về cuốn Di Dân, The

Emigrants đi. Cuốn sách thì đầy cây cối. Thiên nhiên là

nạn nhân thứ nhì mà nó ca ngợi, celebrate, sau người Do Thái.

W.G. Sebald:

Di dân khởi từ 1 cú

điện thoại của bà cụ thân sinh của tôi. Bà gọi để báo cho tôi biết về 1 ông

thày cũ của tôi, ở Sonthofen, tự tử. Cũng không lâu sau cái chết của Jean

Améry, cũng tự tử, và lúc đó tôi đang viết về ông ta. Có vẻ như là có 1 sự

xuất hiện của một chòm sao liên quan tới vấn đề sống sót và vấn đề “chậm

pha”, [không phải “lệch pha”], tức sự quá trễ nải giữa tai ương bất công

và khi mà nó, sau cùng, nhận chìm bạn [A sort of constellation emerged about

this business of surviving and about the great time lag between the infliction

of injustice and when it finally overwhelms you].

Tôi bắt đầu mơ hồ hiểu ra tất cả câu chuyện này, trong trường hợp vị thày

dạy cũ. Và cú phôn làm bật tung ra những hồi ức khác mà tôi có.

CA:

Như vậy vị thày ở trong câu chuyện thứ nhì, là có thực, Paul Bereyter, và

những người khác nữa, đều có thực?

Và nếu như thế, toàn chuyện có thực?

WGS:

Cơ bản mà nói, thì đúng như vậy, với những thay đổi nho nhỏ…

Ghost Hunter

Eleanor Wachtel [CBC Radio’s Writers & Company on April 18, 1998]:

Sebald viết một kinh cầu cho một thế hệ, trong Di dân, The Emigrants, một cuốn sách khác thường về hồi nhớ, lưu vong, và chết chóc. Cách viết thì trữ tình, lyrical, giọng bi khúc, the mood elegiac. Ðây là những câu chuyện về vắng mặt, dời đổi, bật rễ, mất mát, và tự tử, người Ðức, người Do Thái, được viết bằng 1 cái giọng hết sức khơi động, evocative, ám ảnh, haunting, và theo cách giảm bớt, understated way. Di dân có thể gọi bằng nhiều cái tên, một cuốn tiểu thuyết, một tứ khúc kể, a narrative quartet [Chắc giống Tứ Khúc BHD của GCC!], hay, giản dị, không thể gọi tên, sắp hạng. Ông diễn tả như thế nào?

WG Sebald: Nó là một hình thức của giả tưởng văn xuôi, a form of prose fiction. Theo tôi nghĩ, nó hiện hữu thường xuyên ở Ðại lục Âu châu hơn là ở thế giới Anglo-Saxon, đối thoại rất khó chui vào cái thứ giả tưởng văn xuôi này….

EW: Một nhà phê bình gọi ông là kẻ săn hồn ma, a ghost hunter, ông có nghĩ về mình như thế?

WGS: Ðúng như thế. Yes, I do. I think it’s pretty precise…

The destruction of someone's native land is as one with that person's destruction. Séparation becomes déchirure [a rendingl, and there can be no new homeland. "Home is the land of one's childhood and youth. Whoever has lost it remains lost himself, even if he has learned not to stumble about in the foreign country as if he were drunk." The ‘mal du pays’ to which Améry confesses, although he wants no more to do with that particular pays—in this connection he quotes a dialect maxim, "In a Wirthaus, aus dem ma aussigschmissn worn is, geht ma nimmer eini" ("When you've been thrown out of an inn you never go back")—is, as Cioran commented, one of the most persistent symptoms of our yearning for security. "Toute nostalgie," he writes, "est un dépassement du présent. Même sous la forme du regret, elle prend un caractère dynamique: on veut forcer le passé, agir rétroactivement, protester contre l'irréversible." To that extent, Améry's homesickness was of course in line with a wish to revise history.

Sebald viết về Jean Améry: Chống Bất Phản Hồi: Against The Irreversible.

[Sự huỷ diệt quê nhà của ai đó thì là một với sự huỷ diệt chính ai đó. Chia lìa là tan hoang, là rách nát, và chẳng thể nào có quê mới, nhà mới. 'Nhà là mảnh đất thời thơ ấu và trai trẻ của một con người. Bất cứ ai mất nó, là tiêu táng thòng, là ô hô ai tai, chính bất cứ ai đó.... ' Cái gọi là 'sầu nhớ xứ', Améry thú nhận, ông chẳng muốn sầu với cái xứ sở đặc biệt này - ông dùng một phương ngữ nói giùm: 'Khi bạn bị người ta đá đít ra khỏi quán, thì đừng có bao giờ vác cái mặt mo trở lại' - thì, như Cioran phán, là một trong những triệu chứng dai dẳng nhất của chúng ta, chỉ để mong có được sự yên tâm, không còn sợ nửa đêm có thằng cha công an gõ cửa lôi đi biệt tích. 'Tất cả mọi hoài nhớ', ông viết, 'là một sự vượt thoát cái hiện tại. Ngay cả dưới hình dạng của sự luyến tiếc, nó vẫn có cái gì hung hăng ở trong đó: người ta muốn thọi thật mạnh quá khứ, muốn hành động theo kiểu phản hồi, muốn chống cự lại sự bất phản hồi'. Tới mức độ đó, tâm trạng nhớ nhà của Améry, hiển nhiên, cùng một dòng với ước muốn xem xét lại lịch sử].

L'homme a des endroits de son

pauvre coeur qui n'existent pas encore et où la douleur entre afin qu'ils

soient.

Trái tim đáng thương của con người có những vùng chưa hề có, cho đến khi

đau thương tiến vào. Và tạo ra chúng. Léon Bloy.

W.G. Sebald trích dẫn, làm đề

từ cho bài viết "Sự Hối Hận Của Con Tim: Về Hồi Ức và Sự Độc Ác trong Tác

Phẩm của Peter Weiss", The Remorse of the Heart: On Memory and Cruelty in

the Works of Peter Weis, trong "Lịch sử tự nhiên về

huỷ diệt, On the natural history of destruction", nhà xb Vintage Canada,

Anthea Bell dịch, từ tiếng Đức.

… Weiss to attend the Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt. He may also have been

motivated before the event by the hope, never quite extinguished, "that every

injury has its equivalent somewhere

and can be truly compensated for, even if it be through the pain of whoever

inflicted the injury." This idea, which Nietzsche thought was the basis of

our sense of justice and which, he said, "rests on a contractual relationship

between creditor and debtor as old as the concept of law itself”…

W.G.

Sebald: The Remorse of the Heart.

On Memory and Cruelty in the

Work of Peter Weiss

Note: Ðây có lẽ là tác phẩm

tuyệt vời nhất của W.G. Sebald.

Mấy lần đi giang hồ vặt, GCC đều mang theo nó.

Thấy an tâm.

Thư tín:

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

6:39 AM

Thấy bác giới

thiệu (hâm mộ) về W.G. Sebald trên Tinvăn mà...thèm. Tiếc là sách của ông

toàn tiếng Anh mà ở Việt Nam cũng khó mà lùng cho ra. Hơn nữa, ông còn là

một nhà thơ, làm sao để tiếp cận được tác phẩm của ông, dù chỉ chút ít?

Vẫn luôn chờ đợi các bài dịch thơ Adam Zagajewski, Simic... của bác!

Chúc bác khỏe và vui luôn!

Kính mến

Phúc đáp:

Ða tạ.

“Hâm mộ” là từ của 1 vị độc giả, rất mê W.G. Sebald. Trước giờ TV giới thiệu

ông, nhưng vẫn đinh ninh chẳng ai thèm đọc! Một vị độc giả, 1 bạn văn VC

rất thân của Gấu, quen nhân lần về HN, chẳng đã viết mail, rất ư bực bội,

làm sao mà cứ nhắc hoài đến… Lò Thiêu, nó có liên can gì đến giống Mít?

Chính là nhờ vị độc giả hâm mộ Sebald mà GCC mừng quá, nghĩ thầm vậy là

không uổng công mình lèm bèm hoài về ông, và bèn lèm bèm tiếp!

V/v W.G Sebald, thi sĩ.

Trên TV đã từng giới thiệu Sebald,

thi sĩ.

Bài trên Người Kinh Tế giới thiệu

cuốn sắp ra lò, mới tinh về ông.

Trong khi chờ đợi, chúng ta đọc đỡ ở đây:

Người ghi chú cô đơn: The Solitary Notetaker.

Khi W.G. Sebald mất vì tai nạn xe hơi vào Tháng Chạp 2001, ông được tưởng niệm, như là một trong những nhà văn lớn lao của thời chúng ta. Tuy nhiên, khi cuốn đầu của ông, Di Dân, được dịch ra tiếng Anh vào năm 1996, rất ít người bên ngoài nước Đức biết đến ông. Nhưng liền sau đó, ông được đón đọc, tác phẩm liên tiếp được dịch, lẹ làng, đến mức kinh ngạc.

Susan Sontag đã từng tự hỏi, trên tờ TLS, liệu "văn chương lớn" có còn không, và bà tự trả lời, còn chứ, Sebald đó.

Tuy nhiên, kể từ khi ông mất, có nhiều cái nhìn khác nhau về ông. Lớn lao, số một, giọng không giống ai, vẫn đúng đấy, nhưng đọc kỹ hơn, gần hơn, nghe ra có nhiều vay mượn. Tác phẩm của ông, có thể nói, một nửa là do uyên bác, nửa còn lại, là tưởng tượng và kinh nghiệm của riêng ông.

Nếu có một nhà văn vay mượn rất nhiều từ những nhà văn khác, nhưng vẫn là một thứ đồ zin, đồ xịn, thì đúng là Sebald.

Charles Simic, trên NYRB điểm hai cuốn mới nhất của ông, Campo Santo, một thứ tiểu luận, và Unrecounted, gồm 33 bài thơ nho nhỏ, của ông, và 33 bức họa, của Jan Peter Tripp.

Họa: Mỗi bức là một đôi mắt, với sự chính xác, của hình chụp: Proust, Rembrandt, Beckett, Borges... Chủ đề của họa: Miệng thì tốt, để nói dối, trong khi mắt, khó nói dối. Bất cứ mắt đang mơ mộng, hay suy tư, chúng đều vọng một tí ti sự thực, nào đó. Dưới mỗi đôi mắt, là một bài thơ mini. Thí dụ, dưới cặp mắt của Maurice, chú chó của Sebald, là:

Please send me

the brown overcoat

from the Rhine valley

in which at one time

I used to ramble the night.

[Hãy gửi cho tôi

cái áo choàng mầu nâu

từ thung lũng sông Rhine

mà có lần tôi mặc dạo đêm].

Thơ của ông thực sự cũng khó mà gọi là thơ. Như nhà phê bình Andrea Kohler chỉ ra, đó không phải là ngụ ngôn, mà cũng chẳng phải thơ. Chỉ là những cú xổng chuồng, thoáng chốc, của tư tưởng, của hồi nhớ, những khoảnh khắc loé sáng, ở mép bờ của cảm nhận.

Và đây là một bài thơ mini thật thú vị:

Người ta nói,Nã Phá Luân mù mầu [color-blind]

Máu đối với ông ta,

thì xanh như lá cây.

Trước giờ, tuy giới thiệu Sebald, nhưng thú thực, GCC chẳng hề nghĩ, sẽ có ngày nhận được 1 cái mail của độc giả liên quan tới ông người Ðức tốt này. Thế rồi nhận được của 1 vị, rất hâm mộ Sebald.

Thú thực, lại thú thực, GCC

mê đọc những bài tản văn ngắn của ông, những tiểu luận, nhất là tập tiểu

luận “Về lịch sử tự nhiên về huỷ diệt”, On the natural history of destruction.

Tác phẩm Campo Santo, gồm tản văn

và tiểu luận cũng thú lắm.

“Ðất

dụng võ của tôi là tản văn, không phải tiểu thuyết”, “My medium is prose,

not the novel”, ông cho biết. Trong bài giới thiệu tác phẩm Campo Santo, Sven Meyer, người dịch,

phán, vào cuối đời, nhà tiểu luận hết còn phân biệt được với nhà văn.

Câu của Sunday Times, thổi Sebald, đúng chỉ

1 nửa. Sebald vs Borges, OK, nếu chỉ nói về mặt văn chương. Nhưng thời của

Sebald là của Lò Thiêu. Borges, vô thời.

Publisher's Note

Campo Santo brings together pieces written

over a period of some twenty years touching, in typical Sebaldian fashion,

on a variety of subjects. None has been previously published in book form,

but the ideas expressed in 'Between History and Natural History'

will be familiar to some readers - the essay is the predecessor of the Zurich

lectures which later became the backbone of On the Natural History of Destruction.

WG Sebald's last book, Campo

Santo, offers further proof of his rare gift for tackling Germany's pain,

says Jason Cowley

Sunday February 27, 2005

The Observer

Sampo Santo, cuốn sách sau chót của Sebald, đưa ra thêm chứng liệu cho thấy tài năng quí hiếm của ông, trong cái việc sờ vô nỗi đau của Ðức.

Bài điểm này trên tờ Observer,

tuyệt quá.

TV tính dịch, đăng bài giới thiệu cuốn trên, của Sven Meyer, nhưng thôi,

"tùy tiện" mình chơi bài này trước.

Trong những kỳ tới GCC sẽ giới thiệu mấy bài viết trong Về lịch sử tự

nhiên của huỷ diệt.

Ðể đáp lại thịnh tình của vị độc giả hâm mộ Sebald!

“And so they are ever returning to us, the dead.”

James Wood writes about W.G. Sebald's 'Austerlitz'

The destruction of someone's native land is as one with that person's destruction. Séparation becomes déchirure [a rendingl, and there can be no new homeland. "Home is the land of one's childhood and youth. Whoever has lost it remains lost himself, even if he has learned not to stumble about in the foreign country as if he were drunk." The ‘mal du pays’ to which Améry confesses, although he wants no more to do with that particular pays—in this connection he quotes a dialect maxim, "In a Wirthaus, aus dem ma aussigschmissn worn is, geht ma nimmer eini" ("When you've been thrown out of an inn you never go back")—is, as Cioran commented, one of the most persistent symptoms of our yearning for security. "Toute nostalgie," he writes, "est un dépassement du présent. Même sous la forme du regret, elle prend un caractère dynamique: on veut forcer le passé, agir rétroactivement, protester contre l'irréversible." To that extent, Améry's homesickness was of course in line with a wish to revise history.

Sebald viết về Jean Améry: Chống Bất Phản Hồi: Against The Irreversible.

[Sự huỷ diệt quê nhà của ai đó thì là một với sự huỷ diệt chính ai đó. Chia lìa là tan hoang, là rách nát, và chẳng thể nào có quê mới, nhà mới. 'Nhà là mảnh đất thời thơ ấu và trai trẻ của một con người. Bất cứ ai mất nó, là tiêu táng thòng, là ô hô ai tai, chính bất cứ ai đó.... ' Cái gọi là 'sầu nhớ xứ', Améry thú nhận, ông chẳng muốn sầu với cái xứ sở đặc biệt này - ông dùng một phương ngữ nói giùm: 'Khi bạn bị người ta đá đít ra khỏi quán, thì đừng có bao giờ vác cái mặt mo trở lại' - thì, như Cioran phán, là một trong những triệu chứng dai dẳng nhất của chúng ta, chỉ để mong có được sự yên tâm, không còn sợ nửa đêm có thằng cha công an gõ cửa lôi đi biệt tích. 'Tất cả mọi hoài nhớ', ông viết, 'là một sự vượt thoát cái hiện tại. Ngay cả dưới hình dạng của sự luyến tiếc, nó vẫn có cái gì hung hăng ở trong đó: người ta muốn thọi thật mạnh quá khứ, muốn hành động theo kiểu phản hồi, muốn chống cự lại sự bất phản hồi'. Tới mức độ đó, tâm trạng nhớ nhà của Améry, hiển nhiên, cùng một dòng với ước muốn xem xét lại lịch sử].

L'homme a des endroits de son

pauvre coeur qui n'existent pas encore et où la douleur entre afin qu'ils

soient.

Trái tim đáng thương của con người có những vùng chưa hề có, cho đến khi

đau thương tiến vào. Và tạo ra chúng. Léon Bloy.

W.G. Sebald trích dẫn, làm đề

từ cho bài viết "Sự Hối Hận Của Con Tim: Về Hồi Ức và Sự Độc Ác trong Tác

Phẩm của Peter Weiss", The Remorse of the Heart: On Memory and Cruelty in

the Works of Peter Weis, trong "Lịch sử tự nhiên về

huỷ diệt, On the natural history of destruction", nhà xb Vintage Canada,

Anthea Bell dịch, từ tiếng Đức.

I Remember

W.G. Sebald

The day in

the year after

the fall of the

Soviet Empire

I shared a cabin

on the ferry

to the Hoek

of Holland with

a lorry driver

from Wolverhampton.

He& twenty

others were

taking super-

annuated trucks

to Russia but

other than that

he had no idea where

they were heading. The gaffer

was in control &

anyway it was

an adventure

good money & all

the driver said

smoking a Golden

Holborn in the upper

bunk before

going to sleep.

I can still hear

him softly snoring

through the night,

see him at dawn

climb down the

ladder: big gut

black underpants,

put on his sweat-

shirt, baseball

hat, get into

jeans & trainers,

zip up his

plastic holdall,

rub his stubbled

face with both his

hands ready

for the journey.

I'll have a

wash in Russia

he said. I

best of British. He

replied been good

to meet you Max.

Note: Trên tờ Ðiểm Sách London

16 Oct 2011, có bài viết về cuốn Austerlitz của Sebald, của James

Wood, thật tuyệt.

Cuốn này thì cũng “Xưa rồi Diễm ơi”, Sebald thì có thể đầu thai kiếp khác

rồi, nhưng bài viết thì thật là mới, và có gì liên quan tới câu hỏi, làm

thế nào viết sau Lò Thiêu, chỉ nội về... văn phong mà thôi?

Dòng ý thức, độc thoại nội tâm, hậu hậu hậu?

TV sẽ giới thiệu. Gấu cũng mới vớ được 1 cuốn của James Wood, How Fiction

Works trong có bài về ‘dòng ý thức’, thú lắm.

Tính giới thiệu nhân thiên hạ đang lèm bèm về nó.

Có hai Wood, một James, một Michael Wood, đều viết phê bình, và đều nổi tiếng.

Sebald 2

Tưởng

Niệm 1

Phát

biểu khi là ông Hàn

Sân

Trường Cũ

IN MEMORIAM

W. G. SEBALD

Sebald, [mi lại tự thổi rùi],

là do TV khám phá ra, với độc giả Mít. Còn nhớ, khi đó, Gấu bị một đấng bạn

văn VC rất thân, rất quí, và rất đội ơn, mail mắng vốn, Lò Thiêu thì mắc

mớ gì đến xứ Mít, tại sao anh cứ lải nhải hoài về nó?

Sau này, thì Gấu hiểu ra, anh bạn mình bị nhột. Và khi giới thiệu S, người

Gấu đề tặng là anh bạn này.

Sebald quả đúng là 1 típ Ðức

tốt, The good German. Chẳng mắc mớ gì tới tội ác

Lò Thiêu, nhưng không làm sao cư ngụ ở Ðức được, và đành kiếm 1 xó ở Anh

cho qua ngày đoạn tháng. Viết văn bằng tiếng Ðức, nhưng, như những nhà phê

bình chỉ ra, tiếng Ðức của ông cũng bị lệch pha so với dòng chính, nước mẹ

có coi ông là đứa con thì coi bộ cũng hơi bị kẹt.

Ông viết về mình, khi được nhà nước đưa vô Văn Miếu:

Một lần tôi nằm

mơ, và cũng như Hebel, tôi có giấc mơ của mình ở trong thành phố Paris, ở

đó, tôi bị lột mặt nạ, và trơ ra, là một tên phản bội quê nhà, và một tên

lừa đảo. Nhưng, chính vì những nghi hoặc như thế đó, mà việc nhận tôi vô Hàn

Lâm Viện thật rất là đáng mừng, nó có vẻ như một nghi thức sửa sai, phục

hồi mà tôi chưa từng hy vọng.

Chúng ta chưa có 1 nhà văn nào ở vào được vị trí của Sebald để mà nhìn vô cuộc chiến, mà chỉ có những... thiên tài khùng điên ba trợn, trốn lính, bợ đít VC.

Thê thảm chẳng kém, chẳng có 1 tên Bắc Kít "tốt" nào như Sebald.

Ðề tài chủ yếu của những cuốn sách của W.G Sebald là hồi tưởng: đau đớn làm sao, sống có nó; nguy nàn làm sao, sống không có nó, với quốc gia cũng như với cá thể.

You do not have to be an exile to be perceived as a Nestbeschmutzer (one who dirties his own nest) in the German-speaking world - but it helps.

Ðâu cần phải lưu vong để cảm nhận tâm thức của kẻ ỉa đái vô nhà của mình, nhưng, quả là nó có giúp ích!

Vừa mới đây, Gấu

nhận được 1 mail cùa 1 độc giả, nhân đọc TV thấy làm PR cho 1 bài viết về

Sebald trên tờ Ðiểm Sách London,

Gấu thật mừng.

Hóa ra Sbald cũng đã được độc giả Mít để ý tới:

Chào bác,

Em hâm mộ Sebald nhưng không vào được bài bác nói trên LRB. Bác có thể vui

lòng đăng bài James Wood viết về Austerlitz lên Tin Văn được không ạ?

Cảm ơn bác.

Một độc giả Tin văn,

Tks. NQT

OUR WORLD

IN MEMORIAM W. G. SEBALD

I never met him, I only knew

his books and the odd photos, as if

picked up in a secondhand shop, and human

fates found in a secondhand shop,

and a voice quietly narrating,

a gaze that took in so much,

a gaze turned back,

avoiding neither fear

nor rapture;

and our world in his prose, our world, so calm - but

full of crimes perfectly forgotten,

even in lovely towns

on the coast of some sea or ocean,

our world full of empty churches,

rutted with railroad tracks, scars

of ancient trenches, highways,

cleft by uncertainty, our blind world

smaller now by you.

- Adam Zagajewski (Translated from the Polish by Clare Cavanagh)

NYRB April 29, 2004

Thế giới của chúng ta

Tưởng niệm W.G. Sebald

Tôi chưa hề gặp ông, tôi chỉ

biết

những cuốn sách, và những tấm hình kỳ kỳ của ông, như

nhặt ra trong một bán sách cũ, và

số phận con người nhặt ra từ một tiệm đồ cũ

và một giọng âm thầm kể,

một cái nhìn nhìn nhìn quá lâu,

một cái nhìn nhìn lại,

lẩn tránh cả sợ hãi lẫn sung sướng;

và thế giới của chúng ta, trong dòng tản văn của ông,

thế giới của chúng ta, lặng lẽ biết bao, nhưng

đầy những tội ác đã được hoàn toàn quên lãng,

ngay cả trong những thành phố đáng yêu

trên bờ biển hay đại dương nào đó,

thế giới của chúng ta đầy những nhà thờ trống rỗng

hằn vết đường xe lửa, vết sẹo

của những giao thông hào cũ, những đại lộ

rạn nứt bởi sự hồ nghi, thế giới mù lòa của chúng ta,

bây giờ nhỏ hẳn đi, do mất ông

Tình cờ Gấu đọc bản in trong tập thơ Etenal Enemies, thấy có khác với bản in trên báo

OUR WORD

IN MEMORIAM W. G. SEBALD

I never met him, I only knewhis books and the odd photos, as if

purchased in a secondhand shop, and human

fates discovered secondhand,

and a voice quietly narrating,

a gaze that caught so much,

a gaze turned back,

avoiding neither fear

nor rapture;

and our world in his prose,

our world, so calm- but

full of crimes perfectly forgotten,

even in lovely towns

on the coast of one sea or another,

our world full of empty churches,

rutted with railroad tracks, scars

of ancient trenches, highways,

cleft by uncertainty, our blind world

smaller now by you.

Gấu biết đến và tìm đọc Sebald, là do đọc bài viết của Susan Sontag, khen nức nở, thấu “Giời” [Trời, tiếng Bắc Kít]. Bà phán, tưởng thứ khủng long này [nhà văn lớn] tuyệt giống rồi.

Nhưng Gấu khám phá ra 1 Sebald, khác. Với Sontag, là 1 “nhà văn của nhà văn”. Với Gấu, một “tưởng niệm gia” của Lò Thiêu, mà ông không hề mắc mớ, thù hận, hay cảm thấy ân hận, hay phải sám hối.The good German

Absent Jews and invisible executioners: W. G. Sebald and the Holocaust

WILL SELF

[TLS 22.1.2010]

Note: This is an edited text of the 2010 Sebald Lecture, which was delivered in London earlier this month [Jan, 22, 2010]

Ðây là 1 bài viết quan trọng

về W.G. Sebald. TV sẽ cố gắng chuyển qua tiếng Việt.

Chúng ta chưa có 1 nhà văn nào ở vào được vị trí của Sebald để mà nhìn vô

cuộc chiến, mà chỉ có những... thiên tài khùng điên ba trợn, trốn lính, bợ

đít VC...

Ðề tài chủ yếu của những cuốn sách của W.G Sebald là hồi tưởng: đau đớn làm sao, sống có nó; nguy nàn làm sao, sống không có nó, với quốc gia cũng như với cá thể.

You do not have to be an exile to be perceived as a Nestbeschmutzer (one who dirties his own nest) in the German-speaking world - but it helps.

Ðâu cần phải lưu vong để cảm nhận tâm thức của kẻ ỉa đái vô nhà của mình, nhưng, quả là nó có giúp ích!Dans l'herbier de Sebald, les « nervures » du passé

Discret

maître allemand, l'écrivain a brutalement disparu en 2001 dans sa retraite

anglaise, laissant des esquisses d'un projet sur la Corse, récemment éditées.

Par Aliette Armel

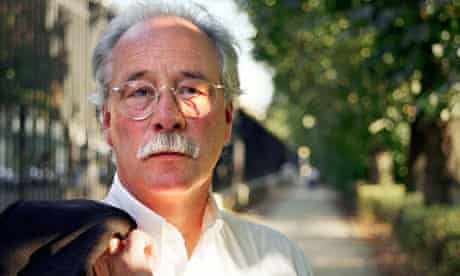

L' image

que le peintre Jan Peter Tripp garde de Max - prénom sous lequel ses amis

connaissaient Winfried Georg Maximilian Sebald - est celle d'un «voyageur fatigué sous les ors

de la cinquantaine ». La discrétion était sa caractéristique première et

la mélancolie se lisait sur son visage. Il se préservait derrière une moustache

drue et de grandes lunettes rondes, derrière deux initiales - W. G. - cachant

le caractère trop allemand de ses prénoms. La célébrité venue, il n'aspirait,

disait-il, qu'à« tout abandonner [ ... ] jusqu'à ce qu'on m'ait oublié et

alors peut-être pourrai-je retrouver cette position où je serai en mesure

de travailler dans mon abri de jardin, sans être dérangé ». La banalité de

sa mort, le 14 décembre 2001, dans un accident de voiture, à proximité de

son domicile de Norwich, en Angleterre, semble s'inscrire dans ce processus

de désagrégation de l'individu dans les accidents de l'histoire dont ses

livres demeurent les témoins, tout autant que de “l'énigmatique survivance

de l'écrit”.

Né le 18 mai 1944 à Wertach-im-Allgaü, village des Alpes bavaroises, Sebald

n'accède à la notoriété internationale qu'en 1996, lors de la traduction

des Émigrants en anglais. Susan Sontag y voit le premier signe de « grandeur

littéraire» apparu depuis longtemps, et « le récit définitif et métaphorique

de notre condition» à travers l'exploration des traces laissées par le passé

et un travail de deuil sur une réalité - le nazisme, l'exil juif, l'Holocauste,

la destruction des villes - se dérobant au langage. Sebald est né dans un

monde fuyant sa mémoire. Il ne connaît son père, officier de l'armée allemande,

qu'en 1947. Lorsqu'il va pour la première fois à Munich, il découvre « quelques bâtiments

intacts, et entre ces bâtiments, une avalanche de gravats ». Cette vision

est pour lui comme une scène originelle. Les questions qu'elle lui pose restent

sans réponse, même à l'université de Fribourg, en Suisse, où il étudie la

littérature allemande: “Les images de ce chapitre effroyable de notre histoire

n'ont jamais véritablement franchi le seuil de la conscience nationale”,

écrira-t-il. L'Holocauste reste, plus encore, enfoui dans le non-dit.

Sebald met à distance la petite ville de Sonthofen, où ses parents se sont

installés en 1952, son pays et même sa langue. Il affirme devoir au hasard

son installation en Angleterre, Manchester

d'abord dans les années 1960, puis, après une tentative de retour en Suisse

alémanique et à Munich, l'université d'East

Anglia en 1976, et une maison

choisie avec sa femme dans un illage. De ce point d'observation à l'écart,

il se plonge dans l'étude: la littérature allemande, romantique tout autant

que du XXe siècle (Kafka, Walser, Peter Handke ou Wittgenstein), mais aussi

l'œuvre de Nabokov ou de Conrad. La quarantaine venue, le cadre des monographies

universitaires lui semble trop étroit. Frappé, au cours d'une recherche,

par les croisements infimes mais multiples entre l'existence d'un botaniste

allemand du XVIIIe siècle - Georg Wilhelm Steller - et l'histoire de sa famille,

il se lance dans l'écriture poétique à partir de ce « rien ». Son premier

triptyque de poèmes en prose, D'après nature, paraît en Allemagne

en 1989.

Dès lors, il utilise les sources et son érudition d'une autre manière. Il

prend comme matériau de l'écrit tout autant la peinture ancienne que contemporaine,

les œuvres publiées que les archives, mémoires, lettres et journaux intimes,

les photographies que les cartes postales. Il arpente l'Europe de l'Est et

du Nord en quête de « ces nervures de la vie passée» où se croisent les destinées

et où se tissent les affinités audelà de l'espace et du temps. Cette exploration

n'a rien de systématique: Sebald se décrit comme un “glaneur”, guidé par

le hasard, par l'émotion que suscitent telle peinture ou telle bribe de texte

résonnant du passé. « Il développait pas à pas une sorte de métaphysique

de l'histoire, écrit-il à propos de l'un de ses personnages, et redonnait

vie à la matière du souuvenir.» Cette quête trouve son expression littéraire

dans une forme libre, évoquant par certains aspects celle de Thomas Bernhard, son modèle. Ses

phrases épousent les méandres du récit. Elles semblent venir d'une autre

époque, s'appuyant sur une pratique tombée en désuétude: l'hypotaxe, caractérisée

par l'abondance des liens de subordination.

Dès Vertiges, paru en Allemagne en 1990, Sebald architecture

le livre autour de plusieurs récits, menés sur le mode biographique (Stendhal,

Casanova) ou de l'autofiction, le personnage du narrateur se confondant avec

celui de l'auteur. Des photographies en noir et blanc sont intégrées dans

le texte: elles ont le statut de documents, accréditant la véracité du récit,

même si, de l'aveu de Sebald, elles ne sont pas toutes authentiques. Ces

images insistent sur les détails dont fourmille le texte. Elles permettent

d'arrêter le temps de la lecture de la fiction, portée par la temporalité

de la narration, mais aussi par le mouvement des digressions et l'exploration

des coïncidences.

Les quatre chapitres des Émigrants (1993) correspondent

à la trajectoire tragique de quatre personnages, Juifs exilés de leur pays

natal, rencontrant Nabokov à un moment de leur histoire. Une structure plus

complexe se déploie dans Les Anneaux de Saturne (1995), illustration

du chaos postmoderne: elle suit les étapes d'un voyage à pied entrepris par

le narrateur sur la côte est de l'Angleterre et le flux de ses rêveries.

Les caractéristiques d'Austerlitz (2001) sont plus romanesques:

quête des origines jusqu'au camp de Terezin, passant par la gare de Liverpool Street,

le quartier de la Bibliothèque nationale de France ou

la forteresse de Breendonk. Ces lieux sont sources d'épiphanies, seules approches

possibles de la vérité selon Sebald.

Des prix consacrent son œuvre, et il est élu à l'Académie allemande. Mais,

en 1997, une série de conférences prononcées à Zurich suscite des commentaires très violents.

Il y revient sur l'élément fondateur de son écriture, les villes allemandes

rasées par les bombardements et le silence obstiné des écrivains sur cet

événement. Il provoque le soupçon d'« amalgame moral» par l'absence de mise

en contexte de cet anéantissement. Il fait face à la polémique en publiant

ces conférences sous le titre De la destruction, comme un

élément de l'histoire naturelle: son indignation contre « la conspiration

du silence» demeure intacte.

Les derniers textes laissés par Sebald révèlent un projet situé, cette fois,

en Méditerranée. Campo Santo évoque les paysages de Corse,

en insistant sur la présence des morts qui y cohabitent avec les vivants:

l'homme discret et mélancolique, l'auteur de la destruction et de la mémoire

s'est senti lié par une nouvelle coïncidence à cette terre où « le royaume

des ombres» s'étend jusqu'en plein jour, sans avoir pu mener à bien l'entreprise

littéraire qu'elle lui aurait inspirée.

VIENNENT DE PARAÎTRE

Campo Santo, W. G. SEBALD, traduit de l'allemand

par Patrick Charbonneau et Sibylle Muller, éd. Actes Sud, 268 p., 21 €.

L’Archéologue

de la mémoire. Conversations avec

W.G. Sebald, édité et préfacé par Lynne Sharon Swartz, traduit de l'anglais

par Delphine Chartier et Patrick Charbonneau, éd. Actes Sud, 190 p., 20 €.

W.G. Sebald.

Le Retour de l'auteur, MARTINE

CARRÉ, Presses universitaires de Lyon, Regards sur l'Allemagne, 2008,320

p., 20 €.

LE MAGAZINE TÉRAIRE AVRIL 2009 N# 485

*

Lời cảm tạ khi được vô Hàn Lâm Viện Đức

W.G. Sebald [1944-2001]

Tôi ra đời vào năm 1944, tại Allgau, thành thử có lúc tôi đã không cảm nhận, hoặc hiểu được thế nào là huỷ diệt, vào lúc bắt đầu cuộc đời của mình. Lúc này, lúc nọ, khi còn là một đứa trẻ, tôi nghe người lớn nói tới một cú, a coup, tôi chẳng có bất cứ một ý nghĩ, cú là cái gì. Lần đầu tiên, như ánh lửa ma trơi, cái quá khứ của chúng tôi đó bất chợt tóm lấy tôi, theo tôi nghĩ, đó là vào một đêm, vào cuối thập niên 1960, khi nhà máy cưa ở Platt cháy rụi, mọi người ở ven thành phố đều túa ra khỏi nhà để nhìn bó lửa cuồn cuộn tuá lên nền trời đêm. Sau đó, khi đi học, phần lớn huỷ diệt mà chúng tôi được biết, là từ những cuộc viễn chinh của Alexander Đại Đế và Nã Phá Luân, chứ chẳng phải từ, vỏn vẹn chỉ, muời lăm năm quá khứ của chúng tôi đó. Ngay cả ở đại học, tôi hầu như chẳng học được gì, về lịch sử vừa mới qua của Đức. Những nghiên cứu Đức vào những năm đó, là một ngành học - mù lòa như dã được dự tính, chỉ đạo từ trước, và, như Hebel sẽ nói - cưỡi một con ngựa nhợt nhạt (1). Trọn một khoá học mùa đông, chúng tôi trải qua bằng cách mân mê Cái Bô Vàng [The Golden Pot] (1), mà chẳng hề một lần băn khoăn, về sự liên hệ ở trong đó, rằng, tại làm sao mà một câu chuyện lạ thường như vậy lại có thể được viết ra, với tất cả những cấu trúc dàn dựng của nó như thế, liền ngay sau một thời kỳ mà xác chết còn ngập những cánh đồng bên ngoài Dresden, và trong tnành phố ở bên con sông Elbe đó thì đang xẩy ra nạn đói, và bệnh dịch. Chỉ tới khi tới Thụy Sĩ, vào năm 1965, và một năm sau, tới Anh, những ý nghĩa của tôi về quê nhà mới bắt đầu được nhen nhúm, từ một khoảng cách xa, ở trong đầu của tôi, và những ý nghĩ này, trong vòng 30 năm hơn, ngày một lớn rộng, nẩy nở mãi ra. Với tôi trọn một thể chế Cộng Hoà có một điều không thực kỳ cục chi chi về nó, như thể một cái gì biết rồi chẳng hề chấm dứt, a never-ending déjà vu. Chỉ là một người khách ở đất nước Anh Cát Lợi, và ở đó thì cũng vậy, tôi như luôn luôn cảm thấy mình lơ lửng, giữa những ý nghĩ, những tình cảm của sự quen thuộc và của dời đổi, bật rễ, không bám trụ được vào đâu. Một lần tôi nằm mơ, và cũng như Hebel, tôi có giấc mơ của mình ở trong thành phố Paris, ở đó, tôi bị lột mặt nạ, và trơ ra, là một tên phản bội quê nhà, và một tên lừa đảo. Nhưng, chính vì những nghi hoặc như thế đó, mà việc nhận tôi vô Hàn Lâm Viện thật rất là đáng mừng, nó có vẻ như một nghi thức sửa sai, phục hồi mà tôi chưa từng hy vọng.

W.G. Sebald

Nguyễn Quốc Trụ dịch [từ bản tiếng Anh, của Anthea Bell, trong Campo Santo, do Sven Meyer biên tập, nhà xb Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Books, 2005]

(1) Pale Rider: Ám chỉ Thần Chết

(2) Tác phẩm

của E.T.A Hoffmann (1814)

*

Viết tệ như thế, ai đọc?

Tháng Chạp năm rồi, một người bạn gửi cho tôi tấm hình trên, kèm một câu, thử viết một cái gì đường được cho nó, nếu có thể. Bức hình nằm trên bàn cả mấy tuần, cứ mỗi lần nhìn nó, là mỗi lần có cảm giác, hình như nó muốn tránh né tôi, cho tới lúc, lời yêu cầu của người bạn, thực sự mà nói, cũng chẳng quá quan trọng, khẩn thiết, trở thành nhức nhối. Thế rồi, một ngày đẹp trời Tháng Giêng, ơ kìa, nhìn kìa, không còn bức hình nữa!

Thời gian trôi đi, tôi chẳng còn nhớ gì về bức hình, cho đến một bữa, chẳng chờ mong, và thật là bất ngờ, nó trở lại, lần này cũng kèm theo một lá thư, từ Bonifacio, của Bà Séraphine Aquavia, một người mà tôi có trao đổi, liên lạc từ mùa hè trước. Trong thư, bà biểu, bà muốn biết tại làm sao lại gửi tấm hình cho bà mà chẳng viết một tí gì về nó, trong thư đề ngày 27 Tháng Giêng của tôi.

Bà cho biết, đó là tấm hình chụp sân trường cũ ở Porto Vecchio bà đã từng theo học vào thập niên 1930. Vào thời kỳ đó, bà viết tiếp, Porto Vecchio gần như là một thành phố chết, ngày này qua tháng nọ bị dịch sốt rét hành hạ, và bao quanh bởi những đầm lầy nước mặn, những bụi còi xanh rậm đến nỗi không thể nào lách qua. Nhiều nhất là một tháng một lần, một cái tầu rỉ sét từ Leghorn tới, chất gỗ sồi lên boong tầu, ngoài bến đò. Ngoài ra, chẳng còn gì, trừ chuyện này: mọi thứ, mọi điều, mọi chuyện cứ thế mà ruỗng nát, hư thối, rỉ sét mãi ra, như đã từng, từ bao đời bao kiếp.

Luôn luôn có một sự im lặng lạ kỳ dọc theo các con phố, kể từ nửa dân cư ở đây chui rúc trong nhà, ban ngày ban mặt, run rẩy vì sốt rét, hay ngồi ở bậu cửa, hay ở hành lang, người vàng ủng, má hóp lại. Chúng tôi, bà Aquavia viết, những học sinh, cũng chẳng có gì để làm, và, lẽ dĩ nhiên, chẳng có một ý nghĩ nào, về sự vô tích sự của những cuộc sống của chúng tôi, ở trong một thành phố gần như bị bệnh sốt rét làm cho không còn có thể ở được nữa.

Như những đứa trẻ của những thành phố khác may mắn hơn, chúng tôi cũng được dậy toán, dậy viết, và được nghe kể giai thoại về sự lên ngôi và xuống ngôi của Hoàng Đế Nã Phá Luân. Thỉnh thoảng, chúng tôi đưa mắt nhìn qua những cửa sổ, vượt qua bức tường bao sân trường, qua màn mầu trắng ở ven đầm nước mặn, quá nữa, tới vùng sáng run rẩy, lấp lánh ở bên trên vùng trời biển Tyrrenian Sea.

Ngoài ra, bà Aquavia kết luận lá thư, chẳng còn kỷ niệm gì về những ngày đi học ở đó, ngoại trừ, điều này, về ông thầy dậy học của chúng tôi, tên là Toussaint Benedetti. Mỗi lần cúi xuống nhìn bài viết của tôi, là, y như rằng, ông nói:

"Ce que tu écris mal, Séraphine! Comment veux-tu qu’on puisse te lire?"

[How badly you write, Séraphine! How do you expect anyone to read it?] (1)

W.G. Sebald: La cour de l'ancienne école [Sân trường cũ].

(1) Phỏng dịch: Hai Lúa viết sao tệ thế! Làm sao độc giả Tin Văn đọc được?

*

Bạn đọc thân mến,

Thêm vào lời chúc mừng Giáng Sinh, và Năm Mới, là bản dịch bài viết của Sebald.

"Hãy viết cho đường được", có thể đó là lời nhắn nhủ lại của ông, qua bài viết thật ngắn này.*

Tưởng niệm Sebald

IN MEMORIAM W. G. SEBALD

January 28, 2010

As several readers of Vertigo have mentioned, an “edited” version of Will Self’s January 11, 2010 lecture on W.G. Sebald has been published in the Times Online. Self touches on several of Sebald’s books and a cast of characters that includes Woody Allen, Albert Speer, Alexander Kluge,Bernhard Schlink, Hannah Arendt, and many others. It’s a complex, dense, thoughtful, broad ranging and controversial speech that is definitely worth reading. Here are a few quotes:

Sebald is rightly seen as the non-Jewish German writer who through his works did most to mourn the murder of the Jews.

To read Sebald is to be confronted with European history not as an ideologically determined diachronic phenomenon – as proposed by Hegelians and Spenglerians alike – nor as a synchronic one to be subjected to Baudrillard’s postmodern analysis. Rather, for Sebald, history is a palimpsest, the meaning of which can only be divined by rubbing away a little bit here, adding on some over there, and then – most importantly – stepping back to allow for a synoptic view that remains inherently suspect.

In England, Sebald’s one-time presence among us – even if we would never be so crass as to think this, let alone articulate it – is registered as further confirmation that we won, and won because of our righteousness, our liberality, our inclusiveness and our tolerance. Where else could the Good German have sprouted so readily?

LE POÈTE

JE RÊVE du matin et rêve du soir; lumière et nuit; lune et soleil et étoiles. La lumière rose du jour et la lumière pâle de la nuit. Les heures et les minutes; les semaines et toute l'année merveilleuse. Plusieurs fois, j'ai levé les yeux vers la lune comme sur l'ami secret de mon âme. Les étoiles étaient mes chers camarades. Quand le soleil a fait briller son or dans le monde pâle et brumeux, comme il m'a rendu heureux ici. La nature était mon jardin, ma passion, ma bien-aimée. Tout ce que j'ai vu était à moi: les bois et les champs, les arbres et les sentiers. Quand j'ai regardé dans le ciel, j'étais comme un prince. Mais le plus beau de tous était le soir. Les soirées étaient des contes de fées pour moi, et la nuit avec ses ténèbres célestes était pour moi comme un château magique plein de secrets doux et impénétrables. Souvent, les sons émouvants d'une lyre joués par un pauvre homme ou un autre transpercaient la nuit. Alors je pourrais écouter, écouter. Alors tout était bon, juste et charmant, et le monde était plein d'une grandeur et d'une joie inexprimables. Mais j'étais joyeux même sans musique. Je me sentais pris au piège des heures. J'ai parlé avec eux comme avec des créatures aimantes, et j'ai imaginé qu'ils me répondaient aussi; Je les regardais comme s'ils avaient des visages, et j'avais le sentiment qu'ils m'observaient aussi en silence, comme avec un étrange œil amical. J'avais souvent l'impression d'être noyé dans la mer, si silencieusement, silencieusement, silencieusement ma vie se déroulait. J'ai cultivé des relations familières avec tout ce que personne ne remarque. A propos de tout ce à quoi personne ne se soucie de penser, j'ai pensé pendant des jours. Mais c'était une pensée douce, la tristesse ne me visitait que rarement. De temps en temps, il me sautait dessus dans ma pièce isolée comme un danseur invisible et me faisait rire. Je n'ai fait de mal à personne et personne ne m'a fait de mal non plus. J'étais si gentiment, merveilleusement séparé.

A Place in the Country by WG Sebald – review

Posthumous publication seems to suit WG Sebald, now a dozen years dead, far more than most writers. He was, after all, in his writing, always in the company of ghosts, both of place and person, in anxious search, as he said, for "how everything is connected across space and time"; the books that have emerged since his absence from the realm of living writers only heighten this unsettling sense of willed limbo.

This collection of essays on half a dozen figures mostly little read in English, including the 19th century Swiss writer Gottfried Keller and the Lutheran poet Eduard Mörike, seems at the outset to have all the attributes of a bottom-drawer manuscript, a scraping together of the inimitable East Anglian emigre's stray thoughts on the influences of his youth. The sense is quickly dispelled, however. Sebald was in possession of the uncanny ability to make his own intellectual obsessions, however abstruse, immediately, compulsively his reader's. Who else, you wonder, in any case, could really get away with an opening sentence like this one?

"In the feuilleton which Walter Benjamin wrote for the Magdeburg Zeitung on the centenary of the death of Johann Peter Hebel, he suggests near the beginning that the 19th century cheated itself of the realisation that the Schatzkastlein des Rhenischen Hausfreunds [Treasure Chest of the Rheinland Family Friend] is one of the purest examples of prose writing in all German literature."

Devotees of Sebald's own prose will greet such a sentence not with trepidation but as a familiar welcome mat to the entirely seductive half-reality of digressive memoir and critical biography and lyrical quest which he invented as his own. I remember the first time I read Austerlitz having a powerful sense of being afforded an aerial view of the strange no-man's land of Sebald's interior life, as if hand-held by the writer in the manner of the Ghost of Christmas Past airlifting the nightshirted Scrooge. We are familiar with the idea of the past seeming another country but no contemporary writer in my experience has ever been more adept in giving time the character of Google Earth geography.

This is one of the more grounded of Sebald's books, though of course it arises from the apparatus of more than one journey – for a start, half of the books he dwells on were those he carried in his suitcase when he set out on his pivotal migration from Switzerland to Manchester as a postwar, post-graduate student of German literature in 1966. The essays are linked, in Sebald's mind at least, by a "behavioural disturbance" – shared between them, and with the author – "that causes every emotion to be transformed into letters on the page and which bypasses life with such extraordinary precision…" Like many essential writers he was drawn to subjects that helped him explain himself to himself, people who were, like him, subject to the "awful tenacity of those who devote their lives to writing".

At least one of these lives is familiar, that of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who Sebald traces in his hyper-productive exile and despair, first on the Ile St Pierre in the Lac de Bienne, later in Wootton in Derbyshire, then Spalding in Lincolnshire, "a godforsaken place set among endless fields of cabbage and beet". The places in the country of the book's title are here, as elsewhere, as much prison as escape.

As the essays progress, other patterns emerge – the writers (he calls them "colleagues") Sebald kept close were instinctive naturalists and cataloguers, annotators and star-gazers looking, like him, for webs of meaning in their often lonely literary projects. His encounter with the novelist Robert Walser, through books and photographs, is perhaps the most affecting of these "extended marginal notes and glosses" to men who were themselves masters of the footnote and addendum.

Sebald claims to see in Walser a reminder of his grandfather, who took him for long formative walks in the country of his childhood, a similarity of bearing that leads him to speculate on "the schemes and symptoms of an order underlying the chaos of human relationships, and applying equally to the living and the dead, which lies beyond our comprehension". Walser withdrew in life first to an attic room, then to an asylum and finally to the "pencil method" of composition – screeds of words only a millimetre high – in which he coded his most indelible work. The trajectory of this life seems emblematic for Sebald of a kind of 20th-century central European journey, born out of the twin demands of the denial of horror and the need to bear witness – territory in which Sebald's own writing was forever mired. You come to see that he prizes Walser, and the others here, for the ingenuity of their strategies of escape from that terrain into the sublime, "those hapless writers trapped in their web of words sometimes succeed in opening up vistas of such beauty and intensity as life itself is scarcely able to provide". Sebald leaves Walser here in a helium balloon, "over a sleeping nocturnal Germany… in a higher, freer realm" – that same kind of transforming condition to which his own writing so stubbornly aspired.

Comments

Post a Comment