Remembering Seamus Heaney

Nhân nói

chuyện dịch thơ, Guardian online kể kinh nghiệm dịch Antigone

của nhà thơ Nobel văn chương, Seamus Heaney. Ông bị bí, và rồi

cảm hứng đã tới với ông, khi ông nhận ra rằng, đừng coi bản dịch của

mình như là một cơ hội để phản đối cuộc chiến Iraq. Đây là một vở kịch

thơ, nhưng bình luận và nghiên cứu đã biến nó trở thành một ẩn dụ chính

trị. Tôi nhắm cái chiều hướng nhân chủng học của tác phẩm, không muốn

bản dịch của mình biến thành một lời chỉ trích cuộc chiến Iraq, vì thế

mà tôi đổi là The Burial at Thebes, thay vì Antigone.

Burial, chôn cất, là vì, chôn hay không chôn, đó là vấn đề; một bên,

quyền của người chết, và một bên, luật của đất. Nhưng chôn là một từ

luôn bám rễ vào đất, nghĩa là, chẳng bao giờ mất đi cái thực tại nguyên

thuỷ của nó. Chôn bảo cho những người còn sống là người chết muốn được

quyền chôn cất, rằng, hãy tỏ lòng tôn kính, với chiếc quan tài, và cái

xác chết ở trong đó, cho dù cái quan tài đó phủ cờ gì.

Đi tìm linh hồn nàng Antigone

Search for the soul of Antigone

Even Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney didn't know how to begin

his translation of Sophocles. Then inspiration struck ...

Wednesday November 2, 2005

The Guardian

Antigone is poetic drama, but commentary and analysis

had turned it into political allegory. What I wanted to point up was

the anthropological dimension of Sophocles' work: I didn't want the

production to end up as just another opportunistic commentary on the

Iraq adventure, and that was why I changed the title.

I called my version The Burial at Thebes partly because

"burial" signals immediately to a new audience what the central concern

of the play is going to be: a contest involving the rights of the dead

and the laws of the land. But mainly I changed the title because

"burial" is also a word that has not yet been divorced from primal

reality. It still recalls to us our destiny as members of a mortal

species and reminds us, however subliminally, of the need to

acknowledge and allow the essential dignity of every human creature. It

implies respect for the coffin, wherever it is being carried, whatever

flag is draped over it, whatever community is crying out alongside it.

It emphasises, in other words, what Hegel emphasised about Antigone,

those "Instinctive Powers of Feeling, Love and Kinship" which authority

must honour and obey if it is not to turn callous.

SH interview

What is your own apology for poetry? What is poetry good for?

To

quote my friend Derek Mahon, they keep the colors new. They rinse

things

[Mi làm

phiền

ta quá. Kiếp trước mi đúng là con đỉa. Mi có lời xin lỗi như thế nào,

đối với ta? Ta đẹp ở chỗ nào?

Tôi xin trích

dẫn bạn tôi: Thơ làm sắc màu luôn tươi rói. Thơ kỳ cọ đời... ].

Remembering Seamus Heaney

SH interview

What is your own apology for poetry? What is poetry good for?

To quote my friend Derek Mahon, they keep the colors new. They rinse things[Mi làm phiền ta quá. Kiếp trước mi đúng là con đỉa. Mi có lời xin lỗi như thế nào, đối với ta? Ta đẹp ở chỗ nào?

Tôi xin trích dẫn bạn tôi: Thơ làm sắc màu luôn tươi rói. Thơ kỳ cọ đời... ].

CITY St Petersburg

I’ve only been to St Petersburg once, about ten years ago. I was interested in it because I’d been reading the poets Mandelstam and Akhmatova, both of whom lived there. It’s a city of beautiful perspectives, with a great sense of the survival of the siege [of Leningrad, 1941-44], and of course there are literary associations at every turn. There’s the so-called "Dostoyevsky area", and the Nevsky Prospect. Mandelstam wrote a poem about the Admiralty Building, and Pushkin wrote one about the bronze statue of St Peter the Great. We visited Joseph Brodsky’s apartment. We’d known him in America, and he’d written about this Soviet "room-and-a-half" where he grew up. We met a friend of his there who’d photographed him on the day of his exile. He’d made a cake, and there was vodka, and we had a little ceremony in memory of Joseph.

Tôi thăm St

Peterbug một lần, cách đây 10 năm. Tôi quan tâm tới nó, bởi là vì tôi

đọc những

nhà thơ Mandelstam và Akhmatova, cả hai sống ở đó. Đó là 1 thành phố

với những

viễn tượng đẹp, với một cảm quan/ý nghĩa lớn, về sống sót cuộc vây hãm,

khi còn

với cái tên là Leningrad, 1941-44, và, lẽ dĩ nhiên, với những hội hè,

hội ngộ,

kết giao văn chương, ở mọi ngõ ngách, bước ngoặt, ở đó. Có cái gọi là

“góc Dos”

[chắc giống “góc Sài Gòn”, “góc Hà Nội”, “góc Thảo Trường”… của TV], và “Toàn Cảnh Nevsky”. Mandelstam đã

từng đi 1 bài thơ về tòa nhà Admiralty Building, và Pushkin, một bài,

về

pho tượng đồng St Peter Đại Đế.

Chúng tôi thăm

căn phòng của Brodsky. Chúng tôi quen biết ông ở Mẽo, và ông đã từng

viết về “căn

phòng rưỡi” Xô Viết này, nơi ông lớn lên. Chúng tôi gặp 1 ông bạn của

ông ở đó,

người đã từng đi 1 pô hình, chụp ông, ngày bị nhà nước VC Liên Xô tống

đi lưu

vong.

Ông bạn này nướng 1 cái bánh, và, kèm thêm 1 chai vốc ka, chúng tôi làm

một

cái tiệc nho nhỏ, tưởng nhớ nhà thơ Joseph của chúng tôi.

Trong căn

phòng rưỡi

Joseph

Brodsky

*

K vừa đưa bài Trong Căn Phòng Rưỡi, và bài thơ Gởi Con Gái Tôi do anh dịch của

Brodsky lên a2a . Đồng thời K link vào bài phim Room and A Half, nói tiếng Nga, xem

cho vui .

Như một món quà SN .

THE ESSAYS OF JOSEPH BRODSKY

In 1986 Joseph Brodsky

published Less Than One, a

book of essays. Some of the essays were translated from the Russian,

others he wrote directly in English. In two cases the English matrix

had a symbolic importance to him: in a heartfelt homage to W H. Auden,

who did much to smooth his path for him when he quit Russia in 1972,

and whom he regarded as the greatest poet in English of the century;

and in his memoir of his parents, whom he had to leave behind in

Leningrad, and who, despite repeated petitions to the Soviet-era

authorities, were never granted permission to visit him. He chose English, he explained, to

honor them in a language of freedom.

Coetzee

Năm 1986, Brodsky cho xb một tuyển tập tiểu luận Less Than One. Một số, dịch từ tiếng Nga, số khác, ông viết thẳng bằng tiếng Anh. Trong hai trường hợp, “ma trận Anh” có 1 sự quan trọng mang tính biểu tượng đối với ông: Bài tôn vinh cảm động, dành cho nhà thơ Anh W.H. Auden, người đã làm cho cuộc bỏ nước ra đi và sống lưu vong nơi xứ người trở nên bớt nặng nề, và, với ông, là nhà thơ vĩ đại nhất của dòng thơ tiếng Anh của thế kỷ; bài viết về bố mẹ và thời gian sống cùng hai bậc sinh thành trong căn phòng rưỡi ở Moscow, thời kỳ Xô Viết, là để vinh danh bố mẹ bằng 1 thứ ngôn ngữ của tự do.

What is your own apology for poetry? What is poetry good for?

To quote my friend Derek Mahon, they keep the colours new. They rinse things..CITY St Petersburg

I’ve only been to St Petersburg once, about ten years ago. I was interested in it because I’d been reading the poets Mandelstam and Akhmatova, both of whom lived there. It’s a city of beautiful perspectives, with a great sense of the survival of the siege [of Leningrad, 1941-44], and of course there are literary associations at every turn. There’s the so-called "Dostoyevsky area", and the Nevsky Prospect. Mandelstam wrote a poem about the Admiralty Building, and Pushkin wrote one about the bronze statue of St Peter the Great. We visited Joseph Brodsky’s apartment. We’d known him in America, and he’d written about this Soviet "room-and-a-half" where he grew up. We met a friend of his there who’d photographed him on the day of his exile. He’d made a cake, and there was vodka, and we had a little ceremony in memory of Joseph.

Remembering Seamus Heaney

THE GUTTURAL MUSE

Late summer,

and at midnight

I smelt the

heat of the day:

At my window

over the hotel car park

I breathed

the muddied night airs off the lake

And watched

a young crowd leave the discotheque.

Their voices

rose up thick and comforting

As oily

bubbles the feeding tench sent up

That evening

at dusk-the slimy tench

Once called

the doctor fish because his slime

Was said to

heal the wounds of fish that touched it.

A girl in a

white dress

Was being

courted out among the cars:

As her voice

swarmed and puddled into laughs

I felt like

some old pike all badged with sores

Wanting to

swim in touch with soft-mouthed life.

-Seamus

Heaney

(1939-2013)

The New Yorker, Sept 9, 2013

SCAFFOLDING

Masons, when

they start upon a building,

Are careful

to test out the scaffolding;

Make sure

that planks won't slip at busy points,

Secure all

ladders, tighten bolted joints.

And yet all

this comes down when the job's done

Showing off

walls. of sure and solid stone.

So if, my

dear, there sometimes seem to be

Old bridges

breaking between you and me

Never fear.

We may let the scaffolds fall

Confident

that we have built our wall.

Làm nhà

Tặng bạn, như một lời tạ lỗi

Những người

thợ khi xây một căn nhà

Thường đắn

đo từng khung cây làm giàn giáo

Sao cho giàn

đừng bung

Ở những nơi

bộn bề công chuyện

Chắt chiu từng

cây thang

Ngại

ngùng từng mối nối

Tất cả bỏ

đi, khi việc xong

Tường đá lộ

ra, uy nghi, sừng sững

Bạn thân ơi,

đôi khi có vẻ

Những cây cầu

ngày xưa gẫy đổ giữa chúng ta

Tâm đắc một điều

Ngôi nhà của chúng ta đã làm xong

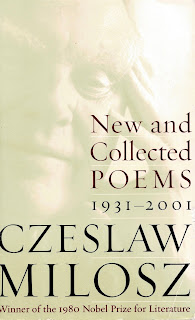

Note: Tập thơ, thấy ghi

mua ngày 17.01.96. Tìm mãi mới thấy.

Bài thơ trên,

lời tặng, tạ lỗi... liên quan tới cô bạn phù dâu ngày nào. GCC

DIGGING

Between my

finger and my thumb

The squat

pen rests; snug as a gun.

Under my

window, a clean rasping sound

When the

spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father,

digging. I look down

Till his

straining rump among the flower beds

Bends low,

comes up twenty years away

Stooping in

rhythm through potato drills

Where he was

digging.

The coarse

boot nestled on the lug, the shaft

Against the

inside knee was levered firmly.

He rooted

out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep

To scatter

new potatoes that we picked

Loving their

cool hardness in our hands.

By God, the

old man could handle a spade.

Just like

his old man.

My

grandfather cut more turf in a day

Than any

other man on Toner's bog.

Once I

carried him milk in a bottle

Corked

sloppily with paper. He straightened up

To drink it,

then fell to right away

Nicking

and

slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his

shoulder, going down and down

For the good

turf. Digging.

The cold

smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap

Of soggy

peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through

living roots awaken in my head.

But I've no

spade to follow men like them.

Between my

finger and my thumb

The squat

pen rests.

I'll dig

with it.

Remembering Seamus Heaney

A shy soul

WHEN Seamus

Heaney began writing poetry, during his years studying to be a

schoolteacher in

the 1960s, he used the pen-name “Incertus”, meaning “uncertain”. Later,

he

would describe himself as “a shy soul fretting and all that”. As an

older man

with an illustrious career behind him his gentle voice could still be

mistaken

for shyness. When I saw him give a lecture at Cambridge University on

the

importance of peaty bogs in his work he stood tall yet slightly stooped

over a

lectern, quietly capturing the audience's attention with his

self-deprecating

dry humour.

Prospero

Một linh hồn cả thẹn

Nobel

prize-winning Northern Irish poet died this morning in a Dublin

hospital after

a short illness

Làm nhà

Tặng bạn, như một lời tạ lỗi

Những người

thợ khi xây một căn nhà

Thường đắn

đo từng khung cây làm giàn giáo

Sao cho giàn

đừng bung

Ở những nơi

bộn bề công chuyện

Chắt chiu từng

cây thang

Ngại

ngùng từng mối nối

Tất cả bỏ

đi, khi việc xong

Tường đá lộ

ra, uy nghi, sừng sững

Bạn thân ơi,

đôi khi có vẻ

Những cây cầu

ngày xưa gẫy đổ giữa chúng ta

Đừng sợ. Hãy

để cho khung rêu rụng xuống

Tâm đắc một

điều

Ngôi nhà của

chúng ta đã làm xong

Books, arts and culture

Remembering Seamus Heaney

A shy soul

WHEN Seamus Heaney began writing poetry, during his years studying to be a schoolteacher in the 1960s, he used the pen-name “Incertus”, meaning “uncertain”. Later, he would describe himself as “a shy soul fretting and all that”. As an older man with an illustrious career behind him his gentle voice could still be mistaken for shyness. When I saw him give a lecture at Cambridge University on the importance of peaty bogs in his work he stood tall yet slightly stooped over a lectern, quietly capturing the audience's attention with his self-deprecating dry humour.

Yet there is little that is hesitant in his poems. “Between my finger and my thumb / The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.” So opens “Digging”, the first poem in “Death of a Naturalist” (1966), his first, dazzling collection. The poem would go on to be studied in schools and endlessly quoted in articles about Heaney, who won the Nobel prize in literature in 1995. Rightly so—in 31 lines Heaney confidently captures the mixture of lyrical observation and matter-of-factness that went on to characterise his work.

Heaney's language is spare and to the point, yet his poems are full with texture. He later wrote that “Digging” was the first poem “where I thought my feelings had got into words, or to put it more accurately, where I thought my feel had got into words.” It was this knack for conveying “the feel” of a thing that marks Heaney out as one of the major poets of the 20th century.

Born in 1939 in County Derry in Northern Ireland Heaney grew up in a rural farmstead, his family crammed into three rooms. As he described it in his Nobel prize speech: “It was an intimate, physical, creaturely existence in which the night sounds of the horse in the stable beyond one bedroom wall mingled with the sounds of adult conversation from the kitchen beyond the other”. The beauty of the Irish landscape recurs throughout his work. He watches his father till the earth and observes potato diggers stopping for their lunch-break. But life is not romanticised. Everyday harsh realities are turned into lyric poetry—farmers drown kittens and dead turkeys are slapped upon the cold marble slabs of a table.

Over 12 collections of poems this rustic upbringing is never far away. But the collection that made his name, “North” (1975) touches on another aspect of contemporary Ireland that has rarely been so well articulated. Describing the sectarian conflict of the 1970s and 1980s, poems such as “Whatever You Say Say Nothing” capture the impossibility of putting such violence into words: “The famous / Northern reticence, the tight gag of place / And times”. “Smoke-signals are loud-mouthed compared with us”, he writes. Few wrote so well and with such nuance about the Northern Irish Troubles.

Along with his poetry, Heaney was also an excellent translator (having studied Latin and Anglo-Saxon at Queen’s University in Belfast). His translation of the Anglo-Saxon poem “Beowulf” in 1995 brought it to a new audience, as did his 2009 version of the little-known, but brilliant medieval Scots poem by Robert Henryson, “The Testament of Cresseid”. His translations of Greek plays, such as “The Burial at Thebes” (adapted from Sophocles’s “Antigone”) and “The Cure at Troy” (a version of Sophocles's “Philoctetes”) subtly interwove differing voices, bridging the gap between poetry and plays. And as a lecturer at Harvard and Oxford (where he was Professor of Poetry from 1989 to 1994) he was a brilliant teacher. His criticism sparkles with the combination of plain speaking and acute observation so familiar in his poems.

Last year I heard Heaney speak again in London. Older, and slightly more frail, his muscular poems still shone out in the darkness of an auditorium. From his last collection, “Human Chain” (2010), he read a poem written in memory of his friend David Hammond. It begins: “The door was open and the house was dark / Wherefore I called his name, although I knew / The answer this time would be silence”. Although death has now silenced Heaney, his voice will live on.

Comments

Post a Comment