SA MẠC TÁC TA

The Tartar Steppe

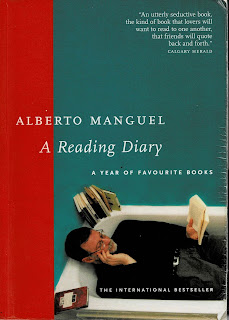

Gấu mua cuốn A Reading Diary Nhật Ký Đọc, cũng lâu rồi. Quăng vào một xó, rồi quên luôn, cho tới khi dọn nhà, nhặt nó lên…

Buzzati notes that, from the very beginning of his writing career, people heard Kafka's echoes in his work. As a consequence, he said, he felt not an inferiority complex but "an annoyance complex." And as a result, he lost any desire to read Kafka's work

Buzzati and Kafka: Perhaps it is not only impossible to achieve justice. Perhaps we have even made it impossible for a just man to persevere in seeking justice.

Buzzati cho biết, vào lúc khởi nghiệp, người ta nói, có mùi Kafka ở trong những gì ông viết ra. Nghe vậy, ông cảm thấy, không phải mặc cảm tự ti, mà là bực bội. Và sau cùng, ông mất cái thú đọc Kafka!

Buzzati và Kafka:

Có lẽ không phải chỉ là bất khả, cái chuyện đi tìm công lý.

Nhưng bất khả còn là vì: Chúng ta làm cho nó trở thành bất khả, để chỉ cho có một thằng cha, cố đấm ăn sôi, cứ đâm sầm vào cái chuyện tìm công lý!

"Không con, thì ai bi giờ hả mẹ?"

[Gửi NTT. NQT]

Gấu đọc Sa mạc Tác Ta [Tartar là một giống dân], bản tiếng Pháp, và không hiểu làm sao, bị nó ám ảnh hoài, câu chuyện một anh sĩ quan, ra trường, được phái tới một đồn biên xa lắc, phòng ngừa sự tấn công của dân Tác Ta từ phía sa mạc phía trước. Chờ hoài chờ huỷ, tới khi già khụ, ốm yếu, hom hem, sắp đi, thì nghe tin cuộc tấn công sắp sửa xẩy ra....

Đúng cái air Kafka!

Trên tờ Bách Khoa ngày nào còn Sài Gòn có đăng truyện ngắn K. của Buzatti. Đây là câu chuyện một anh chàng, sinh ra là bị lời nguyền, đừng đi biển, đi biển là sẽ gặp con quái vật K, nó chỉ chờ gặp mày để ăn thịt. Thế là anh chàng chẳng bao giờ dám đi biển, cho đến khi già cằn, sắp đi, bèn tự bảo mình, giờ này mà còn sợ gì nữa.

Thế là bèn ra Vũng Tầu, thuê thuyền đi một tua, và quả là gặp con K thật. Con quái vật cũng già khòm, sắp đi, nó thều thào bảo, tao có viên ngọc ước quí, chờ gặp mày để trao, nó đây này...

Ui chao Gấu lại nhớ đến Big Minh, thều thào, tao chờ chúng mày để bàn giao viên ngọc quí Miền Nam, và con K bèn biểu, tao lấy rồi, cám ơn lòng tốt của mày!

Doãn Quốc Sĩ, có chuyện Sợ Lửa, tương tự. Đây là câu chuyện một anh chàng sinh ra đời là bị thầy bói nguyền chớ có đến gần lửa. Thế rồi, một ngày đẹp trời, thèm lửa quá, bèn đến gần nó, và ngộ ra một điều, sao mà nó đẹp đến như thế.

Thế là về, và chết!

Gấu cũng thấy lửa rồi. Và đang sửa soạn về...

Sự thực, Gấu không gặp lửa, mà gặp… xác của Gấu, trôi lều bều trên dòng Mékong, lần tá túc chùa Long Vân, Parksé, chờ vuợt sông qua trại tị nạn Thái Lan. Gấu đã kể chuyện này nhiều lần rồi.

Như nhiều cuốn sách yêu thích, cuốn của Buzzati tôi đọc thuở mới lớn, câu chuyện của Drogo, một sĩ quan trẻ được phái đi trấn giữ“Đồn Xa”, ở tận mép bờ sa mạc Tác Ta, và năm này qua tháng nọ, anh bị ám ảnh bởi cái chuyện là, phải chứng tỏ mình là một tên lính xứng đáng trong cuộc chiến đấu chưa hề xẩy ra, với rợ Tác Ta.

Đồn Xa quả là một tiền đồn heo hắt. Và chẳng giống ai. Nó có một hệ thống rắc rối, của những mật ngữ dùng để kiểm tra, khi vô cũng như khi ra.

Tôi [Alberto Manguel] nhớ là đã từng cảm thấy khiếp sợ [và lúc này đang bị] đẩy vào trong một cơn ác mộng của Drogo, gồm đầy những bí mật của những bí mật, của những mật mã, được trao cho, chỉ một vị sĩ quan chỉ huy, và vị này có thể bị mất trí nhớ, hoặc quên mẹ mất đường. Một mạng nhện, của những luật lệ phi lý, sự đe dọa của một kẻ thù vô hình, chúng âm vang, vọng đi vọng lại, rền rền rĩ rĩ, tất cả những nguồn cơn ai oán, những bực bội không lối thoát, vô hy vọng, của một thời mới lớn, và bây giờ, của một người đàn ông đi quá nửa đời người.

*

Ui chao, đọc một cái là nhớ ra, đúng rồi, đúng rồi, đúng là tình cảnh của… Gấu, những ngày ở Sài Gòn!

Nào thử so sánh:

... Bao nhiêu năm, quãng đời vẫn bám cứng. Những giây phút tuy chết chóc, tuy kinh hoàng nhưng sao vẫn có vẻ chi quyến rũ, chi kỳ cục. Cảm giác của một người tuy biết rằng có thể chết bất cứ lúc nào nhưng vẫn loay hoay, cựa quậy: Gã chuyên viên trẻ lui cui chỉnh tín hiệu máy chuyển hình, như đây là tấm cuối cùng, đặc biệt nhất, chất lượng nhất. Gã phóng viên người Mẽo cao như cây sào, chẳng biết một chút gì về máy móc, kỹ thuật, nhưng cũng chăm chú theo dõi, như để nhắc nhở nếu có gì sai sót, và không quên lom khom, cố thu gọn cái thân xác kềnh càng sao cho bằng gã chuyên viên người Việt, ý như vậy là đồng đều nếu chẳng may có một viên đạn bất ngờ. Cả hai cùng lúc nhoài người xuống sàn nhà, có khi còn trước cả một tiếng nổ lớn ngay phía dưới chân building, hay ở Đài Phát Thanh liền bên. Những lúc tiếng súng tạm ngưng, trong khi chờ Tokyo xác nhận chất lượng buổi chuyển hình, và quyết định tấm nào cần lập lại, cả hai chăm chú theo dõi biến động trên bản tin AP, UPI qua máy viễn ký, có cảm giác vừa ở bên trong vừa bên ngoài những giây phút nóng bỏng, và chiến tranh cho đến lúc này, vẫn còn thuộc về những kẻ kém may mắn hơn mình.

... Đêm, vẫn đêm đêm, như hồn ma cố tìm cách nhập xác, như tên trộm muốn đánh cắp thời gian đã mất, mi một mình trở lại Sài-gòn, quán Cái Chùa. Những buổi sáng ghé 19 Ngô Đức Kế, nếu không có Radiophoto cần chuyển, thay vì như người ta trở về nhà chở vợ đi ăn sáng rồi đưa tới sở làm, mi chạy xe dọc đường Tự Do, ngó con phố bắt đầu một ngày rồi ghé quán Cái Chùa làm người khách thứ nhất, chẳng cần ra dấu, người bồi bàn tự động mang tới ly cà phê sữa, chiếc bánh croissant, và mi ngồi trầm ngâm tưởng tượng cô bạn chắc giờ nầy đang ngó xuống trang sách, cuốn tập tại giảng đường Văn Khoa khi đó đã chuyển về đường Cường Để, cũng gần nơi làm việc, tự nhủ thầm buổi trưa có nên giả đò ghé qua, tuy vẫn ghi danh chứng chỉ Triết Học Tây Phương nhưng gặp ông thầy quá hắc ám đành chẳng bao giờ tới Đại Học, nếu có chăng thì cũng chỉ lảng vảng ở khu chứng chỉ Việt Hán. Rồi lũ bạn rảnh rỗi cũng dần dần tới đủ... Lại vẫn những lời châm chọc, khích bác lẫn nhau, đó cũng là một cách che giấu nỗi sợ, nếu đủ tay thì lại kéo tới nhà Nguyễn Đình Toàn làm canh xì.

…. Những ngày Mậu Thân căng thẳng, Đại Học đóng cửa, cô bạn về quê, nỗi nhớ bám riết vào da thịt thay cho cơn bàng hoàng khi cận kề cái chết theo từng cơn hấp hối của thành phố cùng với tiếng hỏa tiễn réo ngang đầu. Trong những giờ phút lặng câm nhìn bóng mình run rẩy cùng với những thảm bom B52 rải chung quanh thành phố, trong lúc cảm thấy còn sống sót, vẫn thường tự hỏi, phải yêu thương cô bạn một cách bình thường, giản dị như thế nào cho cân xứng với cuộc sống thảm thương như vậy...

... Đau khổ nhất là những ngày cô bạn đi lấy chồng. Vẫn những ngày tháng ngây ngô bên mớ máy móc, nghe tiếng người nói xôn xao từ những thành phố xa lạ phía bên ngoài địa ngục, qua đường dây điện thoại viễn liên, mơ màng tưởng tượng chiến tranh rồi sẽ qua đi, cô bạn rồi sẽ hạnh phúc, hạnh phúc... Hết còn nỗi ngây thơ tưởng mình ở trên cao, trên tận đỉnh cồn, thấy hết, hiểu hết. Vẫn những đêm dài điên cuồng đuổi theo bóng mình sợ hãi trốn sâu dưới đáy địa ngục, trong những hang cùng ngõ hẻm thành phố, chạy hoài, chạy hoài, không còn nơi để ghé, không còn chỗ để ngừng... Chỉ mong gặp lại những hồn ma quen, những gã phóng viên người Nhật, người Mỹ, hai gã chuyên viên Phi Luật Tân, để hỏi coi họ có còn luyến tiếc đất nước này hay không, chỉ muốn la lớn, tôi yêu em, tôi yêu em, cho cả thế giới, cả loài người đều nghe...

Cho người chết gật đầu thông cảm.

The Tartar Steppe

Similar to other "end of the world" places-Finisterre, Land's End, Tierra del Fuego-Newfoundland has the quality of standing outside ordinary time. St. John's has something of the Fort in Dino Buzzati's novel The Tartar Steppe (which I reread on my return flight): a place that seems impossible to leave but also impossible to reach, a place so anchored in its own routine that nothing from the outside can touch it. Maybe that is why I found St. John's so appealing.

Favorite cities:

• Venice

• Hobart

• Madrid

• Edinburgh

• Bologna

• Istanbul

• Poitiers

• Selestat

• Oslo

• Bogota

• Tiradentes

• Algiers

• St. John's

Like so many of my favorite books, Buzzati's is one that I first read during my adolescence: the story of Drago, a young man posted to "the Fort" on the edge of the so-called Tartar Steppe, who over the years becomes obsessed with proving himself a soldier in battle with the never materializing Tartars. The Fort is an uneasy haven; a complicated system of passwords controls its entry and exit. I remember feeling (I feel it again now) the terror of being caught in Drogo's nightmare of daily secrets-secrets entrusted to only one commanding officer, who might lose his memory or his way. The web of absurd rules and the threat of an invisible enemy echoed then all the frustrations and helplessness of adolescence; now it echoes all the frustrations and helplessness of more-than-middle age.

Buzzati's Fort exists within the concentric circles of its own rituals; it is a magical place that locks out time. It is not that time has stopped here but that, even more horribly, it continues at its own pace, distancing the Fort from the rest of the cosmos. In a place like this, everything inside you wants to move away; everything outside you keeps you back.

There is a memorable passage in the sixth chapter, describing Drago in his sleep dreaming of the seemingly never-ending journey to the Fort, which he cannot imagine. "Is it far yet? No, you have to cross the river down below there, climb those green hills .... Another ten miles-people will say-just over that river and you'll be there. Instead you never reach the end." I wonder if this is what Alejandra Pizarnik (who certainly had read the novel) had in mind when she wrote that poem I love remembering: "And it is always the garden of lilies on the other bank of the river. If the soul asks, is it far? you shall answer: on the other bank of the river, not this one but that."

Compared to the rain in Newfoundland, the winter rain in France feels warm.

Drogo needs to believe that the Tartars exist and that they pose a threat, so that he can long for the chance to fight them. He needs to believe in the Enemy.

In the paper last week: against the decision of the United Nations, eight European leaders have given their signed approval to Bush-including Vaclav Havel, whom I so admired. Maybe, now that the Communist threat has vanished, he needs to believe in some other Enemy.

Buzzati and Kafka (I): Perhaps it is not only impossible to achieve justice. Perhaps we have even made it impossible for a just man to persevere in seeking justice.

Drogo is aware that time will not stop, that time in the Fort is made of consecutive present moments and that he is a different man in each of those moments. In one of these he wishes he had never come, in another he accepts his condition, in yet a third he hopes he will be a warrior on the battlefield, in a fourth he realizes that none of these present moments will continue to be "now." He describes his mother's attempt "to preserve the time of his childhood" by shutting up his room, and adds, "She was mistaken in believing that she could keep intact a certain state of happiness which had vanished for ever, that she could hold back the flight of time, that if she reopened doors and windows when her son returned, things would be as before."

My first sense of time passing: age six or seven, returning to our house after the holidays and finding that not everything was exactly the same.

On the flight back from St. John's I made these lists:

On the theme of time suspended:

• Bioy Casares, "The Perjury of the Snow"

• James Hilton, Lost Horizon

• Kobo Abe, Woman in the Dunes

• Perrault, "Sleeping Beauty"

• Washington Irving, "Rip Van Winkle"

• Alfonso el Sabio, the fable of the singing bird that makes a hundred years seem like a few minutes, in Las Partidas

On places that cannot be left:

• Leon Bloy, "The Captives of Longjumeau"

• Bunuel, The Exterminating Angel

• Sartre, Huis Clos

• Hans Christian Andersen, "The Snow Queen"

• Tennyson, "The Lotos-Eaters"

On places that cannot be reached:

• Lord Dunsany, "Carcassonne"

• Andre Dhotel, Le pays où l'on n'arrive jamais

• Sir Thomas Bulfinch, My Heart's in the Highlands

• Book of Genesis, the Promised Land (for Moses)

• Kurt Weill, "Youkali"

• Kafka, The Castle

Buzzati notes that, from the very beginning of his writing career, people heard Kafka's echoes in his work. As a consequence, he said, he felt not an inferiority complex but "an annoyance complex." And as a result, he lost any desire to read Kafka's work.

I've just discovered that Lord Byron's dog, Boatswain (for whom he composed a moving epitaph), was born in Newfoundland.

The passwords to get in and out of the Fort are contingent on time. Because they change daily, any soldier who forgets them is in danger of being left outside forever. Coded words must regulate every soldier's existence. The coded language of the military, the conventional language of war, attempts to posit the world in an arbitrary and clear-cut context. Without it, conflict would be impossible.

Buzzati's method of passwords joins Bush's vocabulary of unambiguous terms: good and evil, them and us, black and white, right and wrong. In the twelfth-century Chanson de Roland: "Paiens ont tort et Chretiens ont droit."

Ernest Bramah, in Kai Lung's Golden Hours: "It is scarcely to be expected that one who has spent his life beneath an official umbrella should have at his command the finer analogies of light and shade."

War seems at the same time imminent and yet impossible. The view of the conflict offered by the European newspapers is merely allegorical: American power in the shape of a wilful monster attacking other monsters. Since we don't believe in dragons, the allegory is useless. An editorial in the London Daily Telegraph tells us that the "World Economy requires the War Machinery." We are in the realm of ornamental capital letters.

Ron Wright called this morning from Port Hope. He argues that Bush's bully tactics mark "the end of democracy." I agree. But I wonder whether we can ever witness such titled events on a huge scale ("The Fall of the Roman Empire," "The Conquest of America," "The Holocaust") or whether we are always left with a tiny comer of the picture from which, in the best of cases, we can intuit the whole. It may be that we have to resign ourselves to dealing in details.

Voltaire: "Curse the details, posterity is blind to them all."

The suspect intentions of all sides in this conflict make it difficult to consider it with any clarity. One would require Buzzati's ability to maintain coherence in the midst of constantly shifting points of view. For Buzzati, even the reader's perspective must be brought into the story, since we too must be made responsible for the events. "Look how small they are," Buzzati tells us, pointing at Drogo and his horse, "how small against the side of the mountains, which are growing higher and wilder."

The looming war has nothing heroic about it; we know that the motives driving the Anglo-American forces are less humanitarian than financial. In Buzzati's story, on the other hand, the tragic feeling of absurdity that overcomes the reader stems largely from the utter futility of the heroic enterprise. No humanitarian or financial reasons can be invoked. The frontier gives no trouble, the Tartar Steppe has not seen Tartars in living memory, the heroes are never granted the chance of being heroic.

Drogo: "So the Fort has never been of any use whatsoever?" The Captain: "None at all."

Someone told me this joke: Moishe meets his friend Jacob on the way out of their shtetl. ''I'm leaving for America," says Jacob. "Soon I'll be far away." Moishe: "Far away from what?"

Brilliant sunshine, crisp cold. My neighbor comes over with a gift of fresh eggs and stays for twenty minutes discussing the conflict in Iraq. How strange for an Iraqi farmer half a world away, ifhe were to know that his fate is the subject of a conversation here, in a small, almost invisible French village.

Looking at the soldier who supplies him with the rules and laws governing the passwords, Drogo wonders what is left of him after twenty-two years in the Fort. "Did [he] still remember that somewhere there existed millions of men like himself who were not in uniform? Men who moved freely about the city and at night could go to bed or to a tavern or to the theatre, just as they liked?"

"The eye with which I see God is the same eye with which God sees me," noted Meister Eckhart.

From an apocryphal book of devotions: "God reveals in utter clarity that which we can't understand; that which we can understand He lays out in riddles."

I have often had this idea: that the (false) impression of being able to see in front of us the entire chart of action, the totality of a situation, leads us to believe that other choices are open to us. I say to myself, "I am sitting here, in my room, writing, but I could be elsewhere, doing something quite different," which is like saying, "I could lead another life, I could be someone else."

Buzzati and Kafka (2): Drogo is seized by the unfulfillable desire to escape. "Why had he not left at once? ... Why had he given in?" Drogo's questions reaffirm the ineluctability of his condition. He can imagine escaping only because it is impossible. Kafka in his Diaries: "Should I greatly yearn to be an athlete, it would probably be the same thing as my yearning to go to heaven and to be permitted to be as despairing there as I am here."

In the ninth-century Life and Times of Pai Chu-yi:

"Walking towards the scaffold, Li Tzu turned to his son with these words: 'Ah, if we were in Shanghai, hunting hares with our white hound!'"

I note that the philosopher John Rawls, who died last year, has been remembered by his publishers with this quotation:

The perspective of eternity is not a perspective from a certain place beyond the world, nor the point of view of a transcendent being; rather it is a certain form of thought and feeling that rational persons can adopt within the world. And having done so, they can, whatever their generation, bring together into one scheme all individual perspectives and arrive together at regulative principles that can be affirmed by everyone as he lives by them, each from his own standpoint. Purity of heart, if one could attain it, would be to see clearly and to act with grace and self-command from this point of view.

The Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish: "I am myself alone an entire generation."

My friends Gottwalt and Lucie sent me a magnificent illustrated book on the "Dance of Death" in the Marienkirche in Lubeck, which we visited together a year ago. Against an unremarkable landscape of cities, ports and countryside, every one of society's members is carried away in a macabre chorus line, linking arms with skeletons draped in shrouds. The ordinary atmosphere seems to contradict the monstrosity of death; in fact it grounds it in our daily business, a reminder of what we carry within. That reminder is present all along in Buzzati's work.

Buzzati in his notebooks: "All writers and artists, however long they live, say only one same thing."

In "The Death of Ivan Illich," Tolstoy describes Ivan's progress towards death as like being on a train and having the sudden impression of travelling in the opposite direction, and then being proven wrong. This is the feeling I have throughout The Tartar Steppe, that I am afforded the description not so much of a long death but of a sleep that sometimes resembles wakefulness.

Death and his brother, Sleep: the first version of this image I find in the Epic of Gilgamesh, 2000 B.C.: "The sleeping and the dead, how alike they are, like painted death."

The Tartar Steppe suggests a familiarity with death. I suspect that, in spite of the hundreds of deaths we see every week on our television screens, we have become utterly unfamiliar with it. We hide our dying in hospitals and retirement homes, we make believe that we step from being there to not being there with no transition, as if the screen went suddenly blank. We make no allowance for passage.

I think the skulls which medieval scholars kept on their desks as memento mori were useful acknowledgments of something we will become but which we already carry within us. I'm not sure why we speak of transformation when we refer to dying; we don't change, we merely expose the dust within.

Henri Michaux: "Man, his essential being, IS but a speck. It is this speck that death devours."

The newspaper today describes the work of a German surgeon turned artist who exhibits cadavers of humans and animals in various positions. Apparently, several people have offered to donate their bodies for him to use after their death. Now the surgeon has announced that he will perform a dissection publicly, as a performance piece. The banality of such an exhibition is astonishing. It is that very banality of his use of the dead that renders this man's work obscene.

Tomas Eloy Martinez told me that the actress Norma Aleandro was once visiting a ranch somewhere in Patagonia. The wealthy landowners, proud of their property, displayed for her many of their treasures: valuable paintings, ceramics, books. Encouraged by Aleandro's polite enthusiasm, her hosts said they would show her their favorite piece, and put a small copy of Goethe's poems in her hand. Aleandro commented on the soft, delicately tooled binding. "Yes, that's it," they said. "It's bound in human skin."

I loved someone who died. The last time I was with him, death made him look as if he had woken up in the past, magically young, as he had once been when he was without experience of the world, and happy because he knew that everything was still possible.

A cold, crisp, sunny day.

A friend who has been writing a novel for the past eight years is afraid of finishing it. Draft after draft, revision after revision, she postpones the day of handing it over to the publisher, knowing of course that, once it is printed, all hope of it resembling the novel in her mind will be extinguished, and she will be left with the reality of a creation independent from her will and her desire.

Buzzati and Kafka (3): Drogo hears the news that a battalion of Tartars may at last be approaching the Fort. Feeling too weak to fight, he tells himself that the news will prove mistaken. "He hoped that he might not see anything at all, that the road would be deserted, that there would be no sign of life. That was what Drogo hoped for after wasting his entire life waiting for the enemy."

I finished The Tartar Steppe yesterday. The last pages are astonishing. I walk in the garden as they echo in my mind. The cat follows me.

When Drogo dies (as an old man with his wish to fight the Tartars unfulfilled), Buzzati is there to console him. At the death of Don Quixote, Cervantes finds no words to take leave of his mend, his creation or his creator, and can only stammer, "His spirit departed; I mean to say, he died." At Drogo's death, Buzzati tells his creature that there is still another, better fight waiting for him, not against Tartars, not against "men like himself who were tortured as he was by longing and by suffering, with flesh that one could wound, with faces one could look into," but against "a being both evil and omnipotent." And Buzzati has this to add: "Be brave, Drogo, this is your last card-go to death like a soldier and at least allow your mistaken life to end well. Finally take your revenge on fate; no one will sing your praises, no one will call you a hero or anything like that; but for that very reason it is worth the effort. Step across the shadow line with a firm step, erect as if on parade, and, if you can, even smile. After all, your conscience is not too heavy, and God will certainly grant you pardon."

At the hour of my death, these are the lines I would like to remember.

Comments

Post a Comment