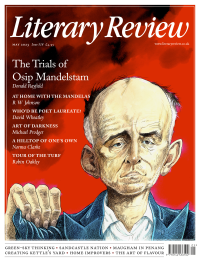

Osip Mandelstam

DONALD RAYFIELD

The Poet & the Tyrant

Osip Mandelstam: A Biography

By Ralph Dutli (Translated from German by Ben Fowkes)

Verso 432pp £25 order from our bookshop

Tristia

By Osip Mandelstam (Translated from Russian by Thomas de Waal)

Arc Publications 130pp £11.99 order from our bookshop

When in 1960 I first came across Osip Mandelstam’s poetry, nobody in the USSR had enjoyed access to his work since the early 1930s and few even knew of his existence, let alone of his death, as he had predicted, in Stalin’s Gulag. His books had been removed from libraries and bookshops. Only braver readers kept them, sometimes hidden in saucepans at their dachas. From 1958, supported by the CIA, émigré scholars collected what they could from Russian publications of the writings of banned Russian authors; the works were so in demand that students like myself copied them out by hand. Impressionable readers were stunned by the hypnotic musicality of Mandelstam’s early poems, by the penetrating appreciation of the disaster that unfolded – the ‘ship of time going to the bottom’ – during the First World War and the Russian Revolution, by the fine love poems and by the use of biology to elucidate his times.

For a student of Russian literature, Mandelstam is a godsend. Every poem has memorable lines that could be quoted in many imaginable situations. Some are frivolous – ‘Eternal is the taste of fresh whipped cream,/As is the smell of orange peel’ – and others gnomic: ‘Everything has been. Everything will be repeated/And only the moment of recognition is sweet.’ Mandelstam absorbed into his poetics a whole century of Russian lyrical poetry, including Pushkin, Lermontov and Tyutchev, as well as Derzhavin, Batyushkov and Baratynsky, so that his poetry seems to be a conversation with the dead. The influence of classical Greek and Latin poets, German Romantics and French symbolists can be discerned too. Yet you also feel the presence of an acutely nervous, highly reactive personality, steeling itself to face forces that threaten him with destruction.

Ralph Dutli has spent half his life translating Mandelstam’s works into German and has combed all the accessible background material. Dutli’s biography, first published in German in 2003, is thorough and fair. With his translation, Ben Fowkes makes it read as if it was written originally in English. It is likely to become the standard reference work for the English reader. Mandelstam himself shunned biography, declaring, ‘The only biography of a writer is a list of the books they have read’. Dutli ignores Mandelstam’s dictum. The people Mandelstam met and, above all, his contretemps with Stalin dominate over his responses to other writers, living and dead.

Dutli is particularly enlightening on the beginning and the end of the poet’s life. Mandelstam was born in Warsaw in 1891 to a Polish-Lithuanian Jewish businessman and a Russophile mother with intellectual aspirations. Like Paul Celan (a Jew from Chernovtsy, now in Ukraine but formerly in Austria, Poland and Romania), he could have written in Yiddish, Polish, Lithuanian or even German. He opted, however, for Russian: the 1900s was a period when, despite widespread anti-Semitism, Jewish writers in the Russian Empire were deserting Yiddish for Russian. Mandelstam received a very European education from the superb teachers at the Tenishev School, where Vladimir Nabokov a decade later also acquired a multilingual and thoroughly cosmopolitan education. By 1910, still a teenager, Mandelstam, urged on by his mother, had shown his juvenilia to the influential editor of a St Petersburg arts magazine, Apollon, and won a circle of admirers, although they were sometimes patronising about Mandelstam’s mannerisms, emotional outbursts and childlike unworldliness. His closest friendship was with a married couple, the poets Nikolai Gumilyov and Anna Akhmatova, with whom he continued all his life to have real or imaginary conversations (even after Gumilyov’s execution in 1921).

During the early 1910s, Mandelstam became an important figure in the Acemist school of poetry, which counted Gumilyov as one of its leading lights. Acemism, Mandelstam said, was characterised by ‘a yearning for world culture’. The Acemists sought to transcend symbolism, taking an almost sculptural view of poetry as something to be carved from ‘hard’ linguistic material. Mandelstam’s first book was called Stone. Works by his fellow Acmeist poets had similarly mineral titles – Gumilyov’s Pearls, Anna Akhmatova’s Beads, Mikhail Zenkevich’s Wild Porphyry. In 1911, Mandelstam had himself baptised in order to register at the University of St Petersburg, but his family’s bankruptcy forced him to go abroad on a study tour of France.

When the First World War broke out, Mandelstam showed hitherto unsuspected maturity, turning away from the war. When revolution followed, he saw it as a historically predetermined disaster. Like several other poets, he moved to the Crimea to avoid starvation. Here he met his future wife, Nadezhda, a practical and proactive partner, in traditional terms more a husband to the poet than a wife (in their letters they sometimes reversed their genders). Mandelstam then spent a year in Georgia, returning to the USSR in 1920. In the wake of the Bolsheviks’ seizure of power, he felt compelled to settle in Moscow. There, he and Nadezhda lived hand-to-mouth, sometimes in ‘grace-and-favour’ flats, sometimes homeless, despite the success of his second book, Tristia, lauded even by Bolshevik critics, who demanded proletarian, not neoclassical, art.

For several years from 1925, Mandelstam abandoned poetry for prose and translation. However, the suicide of the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1930 seemed to awaken in Mandelstam, as it did in Pasternak, the sense that in the USSR poetic silence was futile and doom inevitable. Mandelstam’s poetry, its ideology challenging Stalinism, was now dangerous. Mandelstam had been under the protection of the ‘darling of the party’, the liberal Nikolai Bukharin, but once Stalin began to eliminate those around him, their protégés were doomed. Mandelstam had already publicly protested at the execution of harmless old bank clerks, but in 1934 he made a suicidally reckless move, reciting a lampoon of Stalin, in which the dictator appeared as a demi-god surrounded by semi-human, fairy-tale creatures, at several gatherings in Moscow. Initially, the tyrant was merciful: Mandelstam was allowed to live in Voronezh, five hundred kilometres south of Moscow, for three years. Eventually, however, he was swept away in the feeding frenzy of the Great Terror. He was arrested by the NKVD in May 1938 and died in a transit camp in Russia’s Far East that December.

*

The power and density of the unpublishable poetry he wrote in Voronezh, which only saw the light of day in the 1970s, established him as an immortal. The Voronezh Notebooks, as this work is now called, survived thanks to the efforts of the poet’s courageous widow and a number of foreign and Russian scholars. It was recognisably the product of the same mind, but the writing was now half-encrypted and sometimes difficult to comprehend because of the invocation of modern science. The Mandelstam transformed by exile was to many an alien. Only when Nadezhda smuggled out her memoirs did we get an insight into what had inspired the late poems.

Dutli could have explored more deeply Mandelstam’s Judaism. Although it was for the baptised Russian poet a deplorable source of anxiety and seclusion, it gave him examples of heroism, from biblical episodes to the 15th-century expulsions from Spain and Portugal. As for the poet’s end, Dutli sifts the probable truth from the vague memories of his fellow prisoners in the camp where he died. But Dutli fails to convey Mandelstam’s strange twinship with his nemesis, Stalin, with whom he shared a first name (variants of Joseph). Phonetic coincidence was always meaningful to Mandelstam. One poem could be about either him or Stalin:

A peacock, when he was a boy, would come to play.

They gave him Indian rainbows as a meal,

His milk was poured from rosy-coloured clay,

They didn’t stint the cochineal.

A knot of bones is built up from the pile;

The knees, the hands and shoulders humanised,

He smiles his vast extended smile

And thinks in bone and senses with his forehead

And tries to recollect his human guise.

Mandelstam and Stalin shared an interest in Lamarckism. Stalin was taken with Lamarck’s theory that acquired characteristics could be passed on, a notion that appeared to back up his belief that Homo sapiens would evolve into Homo sovieticus. Mandelstam appreciated Lamarck’s idea that after reaching its peak with Mozart, evolution could go into reverse:

Perhaps before my lips the whispering was born,

In treelessness the wind was blowing leaves,

And those to whom our life work is bequeathed

Have long ago acquired their final form.

For a Western reader with no experience of totalitarianism, perhaps the best parallels to Mandelstam and Stalin’s relationship lie in the distant past. If we read Sir Walter Raleigh’s poems written in the 1610s in the Tower of London, while King James I of England was deliberating whether to put his death sentence into effect, we get a feeling for the situation in which Mandelstam found himself.

Biographers need to attend to the books their subjects read and the music they listened to as well as the places they visited and the persons they loved or hated. The biographer of a poet who wrote in a different language faces another, almost insuperable, difficulty: to provide English versions of the poetry that speak to the reader. Dutli himself has translated every one of Mandelstam’s poems into German. Fowkes occasionally translates Dutli’s German versions into English, but more often makes use of existing English translations of Mandelstam’s poems – some good, like Bernard Meares’s, others less so.

What we have lacked until now is a Mandelstam collection in English where every poem is not only a good translation but also a poem in its own right. Thomas de Waal’s edition of Tristia, with its parallel Russian and English texts, is the first fully successful translation of a whole collection. Tristia’s title is borrowed from Ovid, who was exiled by Emperor Augustus to the Black Sea coast, as Mandelstam was by the civil war. The whole book is imbued with the rhythms of Ovid and Catullus. Its underlying theme is lamentation for a lost world and fear of a new era. Although de Waal warns the reader that Mandelstam can be obscure, his poetry is better described as multilayered and saturated with allusions and meanings, which can be unpacked through repeated readings. De Waal reproduces Mandelstam’s metre and rhythms brilliantly and copes with the near-impossibility of re-creating the richness of Russian in English, where rhymes are too predictable and risk sounding clichéd.

Dutli and de Waal have taken large steps towards enhancing Mandelstam’s reputation among readers in Europe and America. In Russia, he remains a cult figure for a minority: the country today has no time for a poet of Jewish origin and a cosmopolitan outlook. He himself prophetically doubted that there would ever be a Mandelstam Street in Russia – ‘the devil of a name sounds crooked, not straight’. Voronezh, the town where he spent his exile in the 1930s, considered renaming a street after him but decided against it. The world’s only Mandelstam Street is on the campus of Warsaw University.

Khi lần đầu tiên tôi biết đến thơ của Osip Mandelstam vào năm 1960, không ai ở Liên Xô được tiếp cận tác phẩm của ông kể từ đầu những năm 1930 và thậm chí ít người biết đến sự tồn tại của ông, chứ đừng nói đến cái chết của ông, như ông đã dự đoán, trong Gulag của Stalin. Sách của ông đã bị dỡ bỏ khỏi các thư viện và hiệu sách. Chỉ những độc giả dũng cảm hơn mới giữ chúng, đôi khi được giấu trong xoong chảo ở nhà gỗ của họ. Từ năm 1958, được sự hỗ trợ của CIA, các học giả nhập cư đã thu thập những gì họ có thể từ các ấn phẩm tiếng Nga về các tác phẩm của các tác giả Nga bị cấm; các tác phẩm được yêu cầu nhiều đến mức những sinh viên như tôi đã sao chép chúng bằng tay. Những độc giả ấn tượng đã choáng váng trước âm nhạc thôi miên trong những bài thơ đầu tiên của Mandelstam, trước sự cảm nhận sâu sắc về thảm họa đã xảy ra - 'con tàu thời gian đi tới đáy' - trong Thế chiến thứ nhất và Cách mạng Nga, bởi những bài thơ tình hay và bằng cách sử dụng sinh học để làm sáng tỏ thời đại của mình.

Đối với một sinh viên văn học Nga, Mandelstam là một ơn trời. Mỗi bài thơ đều có những dòng đáng nhớ có thể được trích dẫn trong nhiều tình huống có thể tưởng tượng được. Một số thì phù phiếm – ‘Vĩnh cửu là hương vị của kem tươi,/Như mùi vỏ cam’ – và một số khác thì mỉa mai: ‘Mọi thứ đều đã qua. Mọi thứ sẽ được lặp lại/Và chỉ khoảnh khắc nhận ra là ngọt ngào.' Mandelstam hấp thụ vào thi pháp của mình cả một thế kỷ thơ trữ tình Nga, bao gồm Pushkin, Lermontov và Tyutchev, cũng như Derzhavin, Batyushkov và Baratynsky, để thơ ông dường như là một cuộc trò chuyện với người chết. Ảnh hưởng của các nhà thơ cổ điển Hy Lạp và Latinh, các nhà lãng mạn Đức và các nhà biểu tượng Pháp cũng có thể được nhận thấy rõ ràng. Tuy nhiên, bạn cũng cảm nhận được sự hiện diện của một nhân cách cực kỳ lo lắng, có tính phản ứng cao, đang rèn luyện bản thân để đối mặt với những thế lực đe dọa hủy diệt anh ta.

Ralph Dutli đã dành nửa cuộc đời mình để dịch các tác phẩm của Mandelstam sang tiếng Đức và đã sàng lọc tất cả các tài liệu nền tảng có thể tiếp cận được. Tiểu sử của Dutli, được xuất bản lần đầu bằng tiếng Đức vào năm 2003, rất kỹ lưỡng và công bằng. Với bản dịch của mình, Ben Fowkes khiến nó đọc như thể nó được viết nguyên gốc bằng tiếng Anh. Nó có khả năng trở thành tác phẩm tham khảo tiêu chuẩn cho người đọc tiếng Anh. Bản thân Mandelstam cũng tránh xa tiểu sử, tuyên bố: 'Tiểu sử duy nhất của một nhà văn là danh sách những cuốn sách họ đã đọc'. Dutli phớt lờ câu châm ngôn của Mandelstam. Những người mà Mandelstam gặp và trên hết, những người đối đầu với Stalin chiếm ưu thế trong phản ứng của ông đối với các nhà văn khác, dù còn sống hay đã chết.

Dutli đặc biệt soi sáng sự khởi đầu và kết thúc cuộc đời của nhà thơ. Mandelstam sinh ra ở Warsaw vào năm 1891, là một doanh nhân người Do Thái gốc Ba Lan và một người mẹ theo đạo Nga với khát vọng trí tuệ. Giống như Paul Celan (một người Do Thái đến từ Chernovtsy, hiện ở Ukraine nhưng trước đây ở Áo, Ba Lan và Romania), ông có thể viết bằng tiếng Yiddish, tiếng Ba Lan, tiếng Litva hoặc thậm chí cả tiếng Đức. Tuy nhiên, ông đã chọn tiếng Nga: những năm 1900 là thời kỳ mà mặc dù chủ nghĩa bài Do Thái lan rộng, các nhà văn Do Thái ở Đế quốc Nga vẫn từ bỏ tiếng Yiddish để chuyển sang tiếng Nga. Mandelstam nhận được một nền giáo dục rất châu Âu từ những giáo viên xuất sắc tại Trường Tenishev, nơi Vladimir Nabokov một thập kỷ sau cũng có được một nền giáo dục đa ngôn ngữ và hoàn toàn có tính quốc tế. Đến năm 1910, khi vẫn còn là một thiếu niên, Mandelstam, được mẹ thúc giục, đã giới thiệu tuổi trẻ của mình với biên tập viên có ảnh hưởng của một tạp chí nghệ thuật ở St Petersburg, Apollon, và giành được một vòng tròn ngưỡng mộ, mặc dù đôi khi họ tỏ ra trịch thượng về cách cư xử, sự bộc phát cảm xúc của Mandelstam. và sự phi thế giới như trẻ thơ. Tình bạn thân thiết nhất của ông là với một cặp vợ chồng, hai nhà thơ Nikolai Gumilyov và Anna Akhmatova, những người mà ông đã tiếp tục suốt đời để có những cuộc trò chuyện thực tế hoặc tưởng tượng (ngay cả sau khi Gumilyov bị hành quyết năm 1921).

Vào đầu những năm 1910, Mandelstam đã trở thành một nhân vật quan trọng trong trường phái thơ Acemist, trường phái này coi Gumilyov là một trong những ngọn đèn dẫn đường của nó. Chủ nghĩa Acemism, Mandelstam nói, được đặc trưng bởi 'sự khao khát văn hóa thế giới'. Những người theo chủ nghĩa Acemist đã tìm cách vượt qua chủ nghĩa tượng trưng, coi thơ ca như một thứ gần như điêu khắc như một thứ được chạm khắc từ chất liệu ngôn ngữ 'cứng'. Cuốn sách đầu tiên của Mandelstam có tên là Stone. Các tác phẩm của các nhà thơ Acmeist đồng nghiệp của ông có tựa đề khoáng sản tương tự – Ngọc trai của Gumilyov, Hạt của Anna Akhmatova, Porphyry hoang dã của Mikhail Zenkevich. Năm 1911, Mandelstam đã tự mình làm lễ rửa tội để đăng ký vào Đại học St Petersburg, nhưng sự phá sản của gia đình buộc ông phải ra nước ngoài để du học Pháp.

Khi Chiến tranh thế giới thứ nhất nổ ra, Mandelstam cho đến nay đã thể hiện sự trưởng thành không thể nghi ngờ, quay lưng lại với chiến tranh. Khi cuộc cách mạng diễn ra sau đó, ông coi đó là một thảm họa đã được định trước trong lịch sử. Giống như một số nhà thơ khác, ông chuyển đến Crimea để tránh nạn đói. Tại đây, anh gặp người vợ tương lai của mình, Nadezhda, một đối tác thực tế và chủ động, theo cách nói truyền thống là một người chồng đối với nhà thơ hơn là một người vợ (trong những lá thư của họ đôi khi họ đảo ngược giới tính của mình). Mandelstam sau đó dành một năm ở Georgia, rồi trở về Liên Xô vào năm 1920. Sau khi những người Bolshevik nắm quyền, ông cảm thấy buộc phải định cư ở Moscow. Ở đó, ông và Nadezhda sống tay đôi, đôi khi trong những căn hộ 'ân huệ', đôi khi vô gia cư, bất chấp thành công của cuốn sách thứ hai của ông, Tristia, được ca ngợi ngay cả bởi các nhà phê bình Bolshevik, những người yêu cầu nghệ thuật vô sản, chứ không phải tân cổ điển. .

Trong nhiều năm kể từ năm 1925, Mandelstam từ bỏ thơ để chuyển sang văn xuôi và dịch thuật. Tuy nhiên, vụ tự sát của nhà thơ Vladimir Mayakovsky vào năm 1930 dường như đã thức tỉnh ở Mandelstam, cũng như ở Pasternak, cảm giác rằng ở Liên Xô, sự im lặng trong thi ca là vô ích và diệt vong là điều không thể tránh khỏi. Thơ của Mandelstam, hệ tư tưởng của nó thách thức chủ nghĩa Stalin, giờ đây trở nên nguy hiểm. Mandelstam đã được bảo vệ bởi “con cưng của đảng”, Nikolai Bukharin theo chủ nghĩa tự do, nhưng một khi Stalin bắt đầu loại bỏ những người xung quanh ông, những người được họ bảo trợ đã phải chịu số phận. Mandelstam đã công khai phản đối việc hành quyết các nhân viên ngân hàng già vô hại, nhưng vào năm 1934, ông đã thực hiện một hành động liều lĩnh tự sát, kể lại một bài đả kích Stalin, trong đó nhà độc tài xuất hiện như một á thần được bao quanh bởi những sinh vật bán nhân loại, trong truyện cổ tích. , tại một số cuộc tụ họp ở Moscow. Ban đầu, tên bạo chúa rất nhân từ: Mandelstam được phép sống ở Voronezh, cách Moscow năm trăm km về phía nam, trong ba năm. Tuy nhiên, cuối cùng, anh ta bị cuốn đi trong cơn cuồng ăn của Đại khủng bố. Ông bị NKVD bắt vào tháng 5 năm 1938 và chết trong một trại trung chuyển ở vùng Viễn Đông của Nga vào tháng 12 năm đó.

Sức mạnh và mật độ của những bài thơ không thể xuất bản mà ông viết ở Voronezh, nơi chỉ mới xuất hiện vào những năm 1970, đã khiến ông trở thành một người bất tử. Những cuốn sổ ghi chép Voronezh, như tên gọi của tác phẩm này hiện nay, tồn tại được nhờ vào nỗ lực của người góa phụ dũng cảm của nhà thơ và một số học giả nước ngoài và Nga. Có thể nhận ra rằng nó là sản phẩm của cùng một tâm trí, nhưng chữ viết giờ đây chỉ được mã hóa một nửa và đôi khi khó hiểu vì cần đến khoa học hiện đại. Mandelstam bị biến đổi sau cuộc sống lưu vong đối với nhiều người là một người ngoài hành tinh. Chỉ khi Nadezhda lén mang cuốn hồi ký của mình ra ngoài, chúng tôi mới hiểu rõ điều gì đã truyền cảm hứng cho những bài thơ muộn này.

Dutli lẽ ra có thể khám phá sâu hơn đạo Do Thái của Mandelstam. Mặc dù đối với nhà thơ Nga đã được rửa tội, nó là nguồn gốc đáng lo ngại và ẩn dật, nhưng nó đã cho ông những tấm gương về chủ nghĩa anh hùng, từ những tình tiết trong Kinh thánh đến những vụ trục xuất khỏi Tây Ban Nha và Bồ Đào Nha vào thế kỷ 15. Về phần kết của nhà thơ, Dutli sàng lọc sự thật có thể xảy ra từ những ký ức mơ hồ về những người bạn tù trong trại nơi anh ta chết. Nhưng Dutli không truyền tải được mối quan hệ song sinh kỳ lạ của Mandelstam với kẻ thù không đội trời chung của ông, Stalin, người mà ông có cùng tên (các biến thể của Joseph). Sự trùng hợp về ngữ âm luôn có ý nghĩa đối với Mandelstam. Một bài thơ có thể viết về ông hoặc về Stalin:

Một con công khi còn nhỏ sẽ đến chơi.

Họ đã cho anh ta món cầu vồng Ấn Độ như một bữa ăn,

Sữa của anh được đổ từ đất sét màu hồng,

Họ đã không tiết kiệm cochineal.

Một khúc xương được dựng lên từ đống xương;

Đầu gối, bàn tay và vai được nhân bản hóa,

Anh ấy cười nụ cười rộng mở của mình

Và suy nghĩ bằng xương và giác quan bằng trán

Và cố gắng nhớ lại vỏ bọc con người của mình.

Mandelstam và Stalin có chung mối quan tâm đến chủ nghĩa Lamarck. Stalin bị thuyết phục bởi lý thuyết của Lamarck rằng những đặc điểm có được có thể được truyền lại, một quan điểm dường như củng cố niềm tin của ông rằng Homo sapiens sẽ tiến hóa thành Homo sovieticus. Mandelstam đánh giá cao ý tưởng của Lamarck rằng sau khi đạt đến đỉnh cao với Mozart, quá trình tiến hóa có thể đảo ngược:

Có lẽ trước môi tôi lời thì thầm đã ra đời,

Trong rừng cây gió thổi lá bay,

Và những người mà công việc cuộc sống của chúng tôi được để lại

Đã từ lâu có được hình thức cuối cùng của họ.

Đối với độc giả phương Tây không có kinh nghiệm về chủ nghĩa toàn trị, có lẽ điểm tương đồng tốt nhất với mối quan hệ giữa Mandelstam và Stalin nằm ở quá khứ xa xôi. Nếu chúng ta đọc những bài thơ của Ngài Walter Raleigh viết vào những năm 1610 tại Tháp Luân Đôn, trong khi Vua James I của Anh đang cân nhắc xem có nên áp dụng bản án tử hình của mình hay không, chúng ta sẽ có cảm giác về hoàn cảnh mà Mandelstam đang gặp phải.

Người viết tiểu sử cần chú ý đến những cuốn sách mà đối tượng của họ đã đọc và âm nhạc họ đã nghe cũng như những địa điểm họ đã đến thăm và những người họ yêu hay ghét. Người viết tiểu sử của một nhà thơ viết bằng một ngôn ngữ khác phải đối mặt với một khó khăn khác, gần như không thể vượt qua: cung cấp phiên bản tiếng Anh của bài thơ nói được với người đọc. Bản thân Dutli đã dịch từng bài thơ của Mandelstam sang tiếng Đức. Fowkes thỉnh thoảng dịch các bản tiếng Đức của Dutli sang tiếng Anh, nhưng thường sử dụng các bản dịch tiếng Anh hiện có của các bài thơ của Mandelstam - một số hay, như của Bernard Meares, một số khác thì kém hơn.

Điều chúng ta còn thiếu cho đến nay là một tuyển tập Mandelstam bằng tiếng Anh, nơi mỗi bài thơ không chỉ là một bản dịch hay mà còn là một bài thơ theo đúng nghĩa của nó. Ấn bản Tristia của Thomas de Waal, với các văn bản tiếng Nga và tiếng Anh song song, là bản dịch hoàn toàn thành công đầu tiên của cả một bộ sưu tập. Danh hiệu của Tristia được mượn từ Ovid, người bị Hoàng đế Augustus đày đến bờ Biển Đen, giống như Mandelstam trong cuộc nội chiến. Toàn bộ cuốn sách thấm đẫm nhịp điệu của Ovid và Catullus. Chủ đề cơ bản của nó là lời than thở về một thế giới đã mất và nỗi sợ hãi về một kỷ nguyên mới. Mặc dù de Waal cảnh báo người đọc rằng Mandelstam có thể khó hiểu, nhưng thơ của ông được mô tả tốt hơn là có nhiều lớp và bão hòa với những ám chỉ và ý nghĩa, có thể được giải nén qua việc đọc đi đọc lại. De Waal tái tạo nhịp điệu và nhịp điệu của Mandelstam một cách xuất sắc và đương đầu với việc gần như không thể tạo lại sự phong phú của tiếng Nga bằng tiếng Anh, nơi các vần điệu quá dễ đoán và có nguy cơ nghe có vẻ sáo rỗng.

Dutli và de Waal đã có những bước tiến lớn nhằm nâng cao danh tiếng của Mandelstam đối với độc giả ở Châu Âu và Châu Mỹ. Ở Nga, ông vẫn là một nhân vật được sùng bái đối với một thiểu số: đất nước ngày nay không còn thời gian cho một nhà thơ gốc Do Thái và có tầm nhìn quốc tế. Bản thân ông cũng đã tiên tri nghi ngờ rằng sẽ có Phố Mandelstam ở Nga - 'cái tên quỷ quái nghe có vẻ quanh co chứ không ngay thẳng'. Voronezh, thị trấn nơi ông sống lưu vong vào những năm 1930, đã cân nhắc việc đổi tên một con phố theo tên ông nhưng quyết định phản đối. Phố Mandelstam duy nhất trên thế giới nằm trong khuôn viên Đại học Warsaw.

Comments

Post a Comment