The Gift

A Critic at Large

Six Years Later Ban đồng ca thần kỳ tan rã. Ngay cả Rein và Naiman sau cùng cũng gấu ó lẫn nhau. Trong 1, trong rất nhiều hồi ký, Naiman buộc tội Rein, một lần tham dự 1 bữa tiệc cùng bạn bè, mang theo lon trái cây [trái mơ], và chơi một mình, cả lon. Bobyshev sau cùng qua Mẽo, định cư ở Illinois, ở đó, ông dậy văn chương. Sau khi Brodsky mất, ông có viết về những năm tháng đầu tiên của đời ông, và về cuộc tình tay ba. Trong có 1 xen thật bảnh, là cái lần ông tới thăm bà cô ở Moscow. Lúc đó, Akhmatova cũng đang ghé thành phố, và bà gọi cho ông, nhằm lúc ông không có nhà. Khi ông về, bà cô ngỡ ngàng đến nghẹt thở: Cuốn sách chấm dứt với xen Bobyshev, ở Mẽo, gọi cho Brodsky ở New York. Cả hai cả chục năm đếch thèm nói chuyện với nhau, nhưng Bobyshev có chuyện quan trọng cần nói, và chuyện này liên quan tới Akhmatova, cả hai đành để lòng ghen tuông thù hận qua 1 bên. Câu chuyện quan trọng xong, Brodsky bèn hỏi bạn/kẻ thù: -“Sao, thấy Mẽo thế nào?” -“Cũng hơi bị căng, những đúng là 1 nơi chốn thú vị” -“Thú vị là.. sao?” -“Thì thú vị chứ, rất thú vị, mầu sắc, mặt mũi, không gian, con người, tất cả những thứ đó”. -“Hừm,” Bodsky trả lời bạn, và cúp máy. Mặc dù sức khoẻ tồi tệ (bị tim quật lần đầu vào năm 1976), ông tránh được cái chuyện phải quan tâm đến vật chất, như nhiều người sau ông. Hãy nhớ, cũng thế, khi thời gian của mi tới Alexander Pushkin, nhà thơ muốn nói. Brodsky chẳng bao giờ trở lại Nga. Ông cũng chẳng gặp lại Marina Basmanova, mặc dù ông con trai của họ, Andrei có tới thăm ông ở New York một lần, nhưng hai cha con coi bộ không hợp. Một ông bạn cho biết, ông có gọi người cũ 1 lần, hỏi coi ông có thể mua cho đấng con trai của cả hai 1 cái VCR, ngay cả thế, thì Brodsky đã từng cằn nhằn, ông con bỏ học ngang, đếch chịu kiếm việc làm. Tiếng nói của em, thân thể của em, tên của em Tiếng Anh của ông có thể đảm bảo cho bố mẹ một chừng mức tự do, nhưng có 1 điều nó không làm được: chuyển thơ tiếng Nga của ông thành thơ tiếng Anh. Tất nhiên, ông cố gắng, và không hổ thẹn về cái chuyện thử, mà không được. Ngay khi mà tiếng Anh trở nên khơ khớ, đủ xài, là ông bèn “cộng tác” với những dịch giả của ông, sau cùng, ông lắp ghép, thay thế, supplant, họ. Kết quả thì không quá tệ, như, rất ư là thất thường. Với mọi đoạn thơ, thì thường là từ ba cho đến bốn lỗi – văn phạm, thành ngữ, hay, nghe chối tai. Tệ hơn hết, với những độc giả quen với thơ Anglo-Saxon hậu chiến, những bài thơ dịch của Brodsky biến thành vè, ăn vần với nhau, rhymed, bất cần trở ngại nào chúng gặp phải. Ui chao hóa ra Brodsky cũng gặp khá nhiều chuyện Gấu gặp. V/v những bài tiểu luận viết bằng tiếng Anh & trình độ tiếng Anh của Brodsky. А что до слезы из глаза—нет на нее указа, ждать до дргого раза. Meaning, roughly: “As for the tears in my eyes/ I’ve received no orders to keep them for another time.” Tôi ngồi chờ nàng thật lâu. Cơn mưa vẫn tiếp tục. Cuối cùng, tôi chạy vào bên trong trường tìm nàng. Tôi gặp nàng đứng nói chuyện cùng mấy người bạn học. Nàng rời đám bạn, và hai đứa chúng tôi vừa đứng đợi ngớt mưa, vừa nói chuyện, những câu nói nhạt thếch. Khi mưa ngớt, chúng tôi thản nhiên chào nhau ra về, mỗi người đi một ngả đường. Khi nàng đi được một quãng khá xa, đột nhiên tôi quay lại, và chạy theo, chạy thật nhanh. Tôi bắt kịp nàng, và hỏi, nàng còn yêu tôi hay là không. Nàng lắc đầu. Tôi bảo nàng nói. Nàng nói. Nàng nói thêm, nàng chưa hiểu tình yêu là gì. Tôi mệt và giận, muốn đánh nàng, bất chợt, tôi nhìn thấy tôi, trong tấm kiếng chiếc xe hơi đậu kế bên đường: đầu tóc rũ rượi, thở hổn hển, cánh tay trái lòng khòng, nước mưa rỏ trên khuôn mặt hốc hác, tôi đột nhiên nhận ra khuôn mặt thảm hại của tình yêu, tôi đột nhiên có cảm tưởng đã sống hết đời tôi, đã sống hết mối tình. Tôi bảo nàng đi về, tôi bảo tôi đi về. Tôi hiểu rằng tình yêu của tôi đối với nàng đã hết. Ouvrez-moi cette porte où je frappe en pleurant. Apollinaire Vào năm 1976, Brodsky tái ngộ bạn cũ Loseff ở Mẽo. Loseff trở thành người đọc bảnh nhất, và người quan sát gần gụi nhất, cuộc sống Mẽo của ông. Khi còn ở Leningrad, Loseff, người mê sách, làm biên tập thể thao cho một tạp chí dành cho con nít. Qua Mẽo, lúc đầu, như Brodsky ở Ann Arbor làm việc cho nhà xb Ardis của Proffer, sau dời đi New England, còn với Loseff, là Dartmouth, ở đó, ông dạy văn học Nga cho tới mất vào năm 2009. [Cái chi tiết Brodsky chuyên đi sắm quần áo cũ rồi cho bạn, thật thú vị, vì nó làm Gấu đến vợ chồng Gấu, tới xứ lạnh, đúng vào những ngày bão, một trận bão tuyết 40 độ âm, từ mấy chục năm mới lại xẩy ra. Khi ở nhà tạm trú, một ông bạn văn đem đến biếu 1 cái áo lạnh cũ, y chang anh bạn quí biếu cái áo cộc tay cũ, cái hồi còn ở Sài Gòn, sau 1975, làm đệ tử Cô Ba. Trong những tiểu luận, Loseff có thể nói một số điều mà Brodsky không thể. Ngay cả khi dời Nga đi New York, Brodsky vẫn không nghĩ đây là 1 cuộc đổi đời, vẫn có chút dửng dưng, khi nói về nó. Cũng thường thôi, chẳng ghê gớm chi đâu, khi trả lời bất cứ 1 phỏng vấn viên, America is merely “a continuation of space”, Mẽo chỉ là tiếp nối không gian. Hay là, như trong “Khúc Ru Mỏm Cá Thu”, “Lullaby of Cape Cod” (1) qua bản dịch của Anthony Hecht: Viết từ một Đế Quốc mà những sườn vách khổng lồ của nó lấn dưới biển

[Cách nhìn của Bengt Jangfeldt về thái độ đối với quê hương thứ nhì, Mẽo, của Brodsky, bảnh hơn, và thống nhất hơn, [trên cái nền, “đi là đi một lèo, không nhìn lại”, của Brodsky], so với tác giả bài viết trên Người Nữu Ước. Nhưng bài mới này lại cho chúng ta nhiều chi tiết mới mẻ về Brodsky, thí dụ cái vụ ông bị bắt, giai thoại của Akhmatova về ông em, đã mướn nhà nước VC Liên Xô viết tiểu sử của mình…] … cities one won't see again. The sun [Có những thành phố mà ta sẽ chẳng nhìn thấy nữa. Mặt trời dát vàng lên những khung cửa sổ gía lạnh. Nhưng cũng vậy thôi, [Từ đấy trong tôi bừng nắng hạ], nhưng thôi, kệ mẹ mọi cái thứ rác rưởi, kệ mẹ cả lò chủ nghĩa Cộng Sản, [In spite of all Communism], St. Petersburg của nhà thơ vẫn luôn luôn là “thành phố đẹp nhất trên thế giới”. Sự trở về, là không thể, trước tiên là vì chế độ chính trị khốn kiếp đó, lẽ tất nhiên, nhưng sâu thẳm hơn, là yếu tố tâm lý này: “Con người chỉ dời đổi theo một chiều. Và chỉ từ. And only from. Từ một nơi chốn, từ một ý nghĩ đã đóng rễ ở trong đầu, từ chính hắn ta hay là y thị… nghĩa là, hoài hoài dời xa cái điều mà con người đã kinh nghiệm, đã từng trải. Ngôn Ngữ Lớn Hơn Thời Gian Chống lại con đỉa đói Thời gian, ngấu nghiến tất cả, dẫn tới sự thiếu vắng của cả hai, cá nhân và thế giới, Brodsky động viên tới Từ (the word). Ít nhà thơ hiện đại nào như ông, nhấn mạnh đến như thế, vào khả năng của từ, nhằm dứt nó ra khỏi con đỉa đói thời gian sẽ ngấu nghiến tất cả (all-devouring Time). Niềm tin tưởng này luôn luôn trở đi trở lại trong thơ ông, nhất là ở những dòng thơ chót: That's the birth of an eclogue. Instead of the shepherd's signal, [Đó là sự ra đời của một khúc đồng dao. Thay vì tên chăn cừu dơ tay, hay phất cờ Niềm tin của Brodsky vào quyền năng của từ phải được hiểu theo quan điểm chống thời gian và không gian của ông. Văn chương hơn [superior) xã hội – và hơn nhà văn, chính hắn. Ý tưởng không phải ngôn ngữ, nhưng chính nhà văn, là dụng cụ, ý tưởng này là cốt lõi thơ Brodsky. Ngôn ngữ già hơn xã hội, và lẽ dĩ nhiên, già hơn nhà thơ, và chính ngôn ngữ sẽ nối kết những quốc gia, một khi mà trung tâm không còn giữ nổi, “the centre cannot hold” (chữ của Yeats). Con người chết, nhà văn, không. Cùng phát biểu như vậy, là nhà thơ Anh, W.H. Auden, trong bài thơ tưởng niệm nhà thơ W.B. Yeats, “In Memory of W.B. Yeats (1939). Chính đoạn thứ ba và cũng là đoạn chót của bài tưởng niệm đã gây ấn tượng mạnh ở nơi Brodsky, như ông kể lại trong Less Than One, khi ông đọc bài thơ lần đầu, trong khi lưu đầy nơi mạn bắc nước Nga: Time that is intolerant [Thời gian không khoan dung Nói một cách khác, ngôn ngữ hơn, không chỉ xã hội và nhà thơ, mà còn hơn cả thời gian, chính nó. Thời gian “thờ phụng ngôn ngữ”, và như thế “không bằng, kém, thua” ngôn ngữ. Có một nét bi thương, lãng mạn, như là định mệnh của ngôn ngữ, qua một khẳng định như thế, nhưng ở Nga xô, nơi con người, như Puskhin diễn tả, thường “câm” [mute], và nhà văn có một vị thế độc nhất. Sự nhấn mạnh vào tính trấn ngự của ngôn ngữ do đó, không phải là một biểu hiện của chủ nghĩa mỹ học; trong một xã hội, nơi ngôn ngữ được quốc gia hóa, nơi ngôn ngữ mang mùi chính trị ngay cả khi không nói chính trị, trong một xã hội như thế, từ ngữ có một sức mạnh bộc phá lớn lao, khủng khiếp. Khác hẳn Brodsky, Loseff nhìn đế quốc Mẽo: “Bây giờ, đã sống ở đó 30 năm, tôi đôi khi vẫn cảm thấy một sự phấn kích lạ kỳ, mình đó ư, nhìn đất lạ này, với cặp mắt của chính mìmh, ngửi cái mùi lạ như là mùi của mình, nói tiếng lạ như là tiếng của mình”. Ui chao, trong khi đó, đây là cảm tưởng của một nhà văn Mít, khi phải nhìn cái đất nước đã nhận ông và gia đình ông, và khi phải nhìn lại Đất Mẹ của ông: LTT: ST: Thú thực, trước 1975, Gấu Cà Chớn chưa từng đọc ST. Thành thử không có ý kiến về những gì ông viết cho những tờ báo được ông liệt kê. Sau 1975, ra hải ngoại, đọc ông trên tờ Nắng Mới, của nhóm của ông, mà Gấu cũng có bài đóng góp. Khi đó, ông viết ba cái tạp nhạp, theo kiểu tạp ghi, ghi nhận 1 số tin văn học, thời sự địa phương… Cũng chưa ngửi ra mùi văn của ông. Tiếng Anh của riêng Brodsky tiến bộ rất nhanh. Gần như ngay lập tức khi tới Mẽo, ông bắt đầu cho in những bài tiểu luận, dịch từ tiếng Nga, bởi những bạn bè của ông, trong giới báo chí Mẽo. Vào năm 1977, ông mua 1 cái máy đánh chữ cũ ở Manhattan, và bắt đầu viết tiểu luận bằng 1 thứ tiếng Anh của riêng ông, 1 thứ tiếng Anh mềm mỏng, dễ uốn, giọng điệu chơi chơi, tếu tếu, qua đó, bạn đôi khi nhận ra giọng thơ gốc Nga của ông. Trong những tiểu luận đó, rất nhiều bài xuất hiện trên NYRB, Brodsky viết với tất cả sự chân thành, thân ái của ông về những nhà thơ mà ông ngưỡng mộ nhất: Marina Tsvetaeva, Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, và ở bờ bên kia, Robert Frost, và nhất là, Auden. Bằng cách này, ông trả những món nợ của ông. Ông còn có thể, trong vài bài tiểu luận có tính tự thuật, nhớ lại những kinh nghiệm đau thương của mình trong 1 một hình thức mới [tiếng Anh]. Như ông viết về ông cụ bà cụ của mình, mất vào giữa thập niên 1980, không thể nhìn thấy mặt con, kể từ khi ông bị tống xuất khỏi Liên Xô: Tôi viết thư nhà này bằng tiếng Anh, bởi vì tôi mong cha mẹ tôi được hưởng một chút tự do, một chút tự do này, rộng hẹp ra sao, là còn tuỳ thuộc vào con số những người muốn, hoặc thích đọc thư nhà này. Tôi muốn ba má tôi, Maria Volpet và Alexander Brodsky, có được thực tại dưới “qui tắc ngoại về lương tâm” [a “foreign code of conscience”]. Tôi muốn, những động từ tiếng Anh, về sự chuyển động, diễn tả những chuyển động của hai cụ. Điều này không làm cho hai cụ sống lại, nhưng văn phạm tiếng Anh ít ra cũng chứng tỏ được một điều, đó là con đường giải thoát tốt đẹp hơn, từ những ống khói lò hỏa táng của nhà nước, so với văn phạm tiếng Nga. Viết về họ bằng tiếng Nga chỉ có nghĩa kéo dài thêm sự giam cầm của họ, đẩy họ vào sự vô nghĩa, vô lý, do cái việc hư vô hóa một cách máy móc kia. Tôi biết, không nên đánh đồng nhà nước với ngôn ngữ, nhưng chính là xuất phát từ thứ tiếng Nga đó, mà hai người già cả, đã mò mẫm hết cơ quan này tới cơ quan kia, hết ông cán này tới ông cán khác, với hy vọng có được tờ giấy phép đi ra nước ngoài để thăm đứa con trai độc nhất của họ, trước khi họ chết, và liên tiếp được trả lời, trong mười hai năm trời ròng rã, là nhà nước coi một tờ giấy phép như thế, là “không thích hợp, không có mục đích” [“unpurposeful”]. Chỉ nội chuyện đó không thôi, sự lập đi lập lại một “lời phán” khốn nạn như thế, nó chứng tỏ một sự quen thuộc nào đó, của nhà nước, với tiếng Nga. Ngoài ra, ngay cả chuyện, nếu tôi viết tất cả, bằng tiếng Nga, những từ này cũng chẳng mong chi có một ngày đẹp trời của nó, nhìn thấy ánh sáng mặt trời, dưới bầu trời Nga. Ai sẽ đọc chúng? Một dúm di dân Nga mà cha mẹ của họ, đã chết, hoặc sẽ chết, dưới những hoàn cảnh tương tự? Họ, chính họ, hiểu rõ chuyện này hơn ai hết. Họ hiểu, cái cảm tưởng đó là như thế nào, khi không được phép nhìn mẹ cha của họ, khi ông hay bà nằm trên giường chờ chết; sự im lặng tiếp theo yêu cầu của họ, về một giấy nhập cảnh khẩn cấp, để dự đám tang của người thân. Và rồi thì, mọi chuyện đều quá trễ, và người đàn ông, hoặc đàn bà đặt chiếc ống nghe điện thoại xuống, bước ra khỏi một cánh cửa, bước vào một buổi chiều ở nước ngoài, cảm thấy một điều mà chẳng ngôn ngữ nào có từ ngữ để diễn tả, và dù có la, rú, hét, khóc than cỡ nào cũng vô ích… Tôi sẽ phải nói với những người đó điều gì? Bằng cách chi, tôi có thể an ủi họ? Chẳng có một xứ sở nào đã luyện được cái tay nghề tài tình trong việc huỷ diệt linh hồn của dân mình như nước Nga. Và chẳng có một nhà văn nào lại có thể làm lành lặn linh hồn đó; không, chỉ có Trời, Phật, Thần Thánh mới có thể làm được điều này. Chính là vì lý do đó, mà Đấng Thiêng Liêng kia mới có mặt trong suốt Thời Gian Của Người. Xin cho tiếng Anh làm cái nhà cho những người thân quá cố của tôi. Trong tiếng Nga, tôi được sửa soạn để đọc, viết những dòng thơ, hay lá thư. Tuy nhiên, với mẹ cha tôi, bà Maria Volpert và ông Alexander Brodsky, tiếng Anh mới chính là thứ ngôn ngữ dâng cho họ một cõi sau xem ra tươm tất hơn và có thể đó là cõi duy nhất mà họ có được ngoài cái trí nhớ của bản thân tôi về họ ra. Còn về bản thân tôi, khi viết bằng tiếng này, thì cũng chỉ như là rửa chén dĩa mà thôi, rất tốt cho sức khỏe, như mẹ tôi đã mừng rỡ khi biết thằng con của bà vừa rửa một mớ chén dĩa xong, là bèn gọi điện thoại cho mẹ liền! Bạn đọc TV để ý, chính là bằng cái từ “không thích hợp, không có mục đích” [“unpurposeful”], đám khốn kiếp Sài Gòn sử dụng, theo lệnh Bắc Bộ Phủ, để cấm sô hát tái ngộ của anh chàng ca sĩ Miền Nam gốc Chăm, Lính Chê. Ở Vienna, Brodsky gặp Carl Proffer, một giáo sư văn chương Nga tại Đại học Michigan, ông này vừa mới mở 1 cái nhà xb nhỏ, Ardis. Biết Auden, người hùng của Brodsky, đang nghỉ hè cận đó, ông bèn quyết định kéo Brodsky làm 1 cú viếng thăm. Mặc dù đếch có báo trước cái con mẹ gì cả, nhưng Auden, tỉnh như Ăng Lê, mở rộng cửa đón mừng nhà thơ lưu vong, và vài tháng sau, Brodsky bèn “thư nhà” [chắc giống ông tiên chỉ VP], cho ông bạn của mình, Loseff, sử dụng tiếng Anh búa xua, mới kiếm thấy, gặp chữ nào chơi chữ đó: W. H. Auden uống ly đầu tiên martini dry vào lúc 7.30 sáng. Sau đó, ông đi 1 đường mở hộp thư ra coi, đọc giấy tờ và đánh dấu dịp trọng đại này bằng 1 ly hỗn hợp sherry và scotch. Sau đó, ông chơi breakfast, điểm tâm, kèm với 1 món địa phương dry pink and white. Tôi không nhớ cái nào trước, cái nào sau. Sau đó, ông bắt đầu làm việc. Có thể là do ông dùng bút ballpoint, cho nên bàn làm việc kế ngay bên, và thay vì một lọ mực, thì là 1 chai, hay lon Guinness, một thứ bia đen Ái nhĩ lan, nó từ từ biến mất theo công việc sáng tạo. Tùy theo thực đơn, bữa ăn trưa thì được trang điểm bằng cái đuôi này, hay cái đuôi kia, của một con gà trống, hay cocktail. Sau bữa trưa, thì ngủ trưa 1 phát, và tôi nghĩ, đây là 1 điểm khô độc nhất của ngày. Và như thế đấy, cuộc đời quyến rũ, ngạc nhiên, thích thú của Brodsky ở Tây Phương bắt đầu Brodsky xuất hiện như là 1 món đồ trang sức, kế bên em Susan Sontag, trong cuốn hồi ký về em của tiểu thuyết gia Sigrid Nunez, “Sempre Susan”. Đó là năm 1976, và Brodsky mới bắt đầu hẹn hò mí em. Chàng thì lãng mạn, ủ ê, hói. “Chẳng có gì chó gì hết”, một bữa chàng tuyên bố. “Không đau khổ. Không hạnh phúc. Không đau ốm. Không nhà tù. Không là không.” (Bây giờ, đó là Âu Châu, Nunez viết, khi moi móc về phiá Sontag. [Trong Water Mark, Thuỷ Ấn, Brodsky có viết về lần hẹn hò ở Venise, không biết có phải là cú này không. GCC]) Một lần khác, Brodsky đưa mọi người đi ăn đồ Tầu, món khoái khẩu của ông ở New York. Ngồi quanh bàn, là Sontag với ông con trai, Nunez trẻ, Brodsky trông như 1 cha già La mã lang bạt. Anh miêu tả cái cảnh Brodsky bước vào bộ lạc nho nhỏ của mình, “Chúng mình hạnh phúc phải không?” Cuối cùng, Brodsky chạy trốn xứ sở của những nha sĩ để đổi lấy 1 căn phòng nhỏ có vườn ở Morton Street, West Village, mà ông mướn của 1 vị giáo sư N.Y.U, và có 1 chân dạy học ở Mount Holyoke, Westen Massachusetts. Ông thấy địa vị của mình, có tính xã hội, nghĩa là cũng không đến nỗi cô đơn, một mình, và giọng điệu thư nhà chuyển qua 1 giai điệu kỳ kỳ, “Tuần lễ vừa rồi, tôi có cuộc trò chuyện đầu tiên, trong thời hạn ba năm, về Dante,” một lá thư phàn nàn, “và rồi thì với Robert Lowell” Chẳng có chỗ cho cả hai, Brodsky và chủ nghĩa CS, trong cái xứ sở thật rộng lớn đó. Bè lũ VC Nga bực bội với tất cả những gì Brodsky làm, [cả đến chuyện đi ị, như nhà thơ NCT đã từng, đúng vào ngày sinh nhật Bác]. Andrei Sergeev, bạn của Brodsky, sau đó viết: Nhà chức trách không thể làm bất cứ điều chi ngoài chuyện bực, với tất cả những gì Brodsky làm, không làm, đi tản bộ loanh quanh, đứng, ngồi ở bàn, nằm xuống giường, và ngủ. Brodsky vẫn cố tìm đủ cách xb thơ của ông, vô ích. Tới mức, hai ông cớm KGB gật đầu, chúng tao sẽ in thơ của mày, trên loại giấy đặc biệt, bản quí, dành cho "bạn quí" của mày, nếu mày đi một đường báo cáo về những ông giáo sư, bạn của mi, chỉ là báo cáo xuông, những chuyện làm xàm ba láp thôi. Cuốn này, nghe nói, xb không có sự đồng ý của Brodsky, và có nhiều chi tiết, sự kiện không được chính xác. Tuy nhiên, đọc, thú vô cùng. Cái đoạn KGB bắt Brodsky trình diện, năn nỉ ông nạp đơn xin visa xuất ngoại, kiếm bà con dởm cho ông có lý do để đoàn tụ, thật… tếu. Your voice, your body, your name Tiếng nói của em, thân thể của em, tên của em Brodsky viết về người yêu cũ của chàng. Có nhiều nhà thơ có tài, có thể ở vào chỗ anh ta khi đó, Efim Etkind viết. Nhưng số phận đã chọn đúng anh ta, và ngay lập tức anh hiểu trách nhiệm về địa vị của anh - không còn là một con người riêng tư, nhưng trở thành một biểu tượng, như Akhmatova đã trở thành một biểu tượng quốc gia của người thi sĩ Nga, khi bà bị số phận lọc ra giữa hàng trăm nhà thơ, năm 1946. Thật quá nặng cho Brodsky. Ông có một bộ não tệ, một trái tim tệ. Nhưng ông đã đóng vai ông tại tòa án một cách tuyệt vời. Thế đấy. Theo nghĩa thế đấy, cái vai tuyệt vời mà Ông Giời dành cho thi sĩ mê gái HC, là, khi bị Tố Hữu bắt viết tự kiểm, thì bèn phán, ông đếch viết, được không. Trời sinh ra GCC là để mê… BHD, nhưng khi rảnh rang thì lèm bèm về Cái Ác Bắc Kít! Hà, hà! Trong cuốn này, GCC chôm hai bài, 1 về Brodsky, đọc khi đăng trên The New Yorker, và, về Oe, "Cha và Con". Sau cùng, Ông Tòa bèn ban cho "cái gọi là" thi sĩ, the so-called poet, 5 năm tù lưu vong nội xứ, lao động cải tạo tại Biển Bắc, để phục hồi nhân phẩm, không còn là kẻ ăn bám, ăn hại xã hội chủ nghĩa. Về cái chuyện lưu vong của Brodsky, Loseff, lại một lần nữa không hài lòng với quan điểm của đa số độc giả, vốn quen nghĩ về nhà thơ, như 1 người tù Gulag. Cái vụ ông bị đưa vô nhà thương điên giữa hai lần ra tòa thì thật là thê thảm, nhưng 18 tháng ông trải qua tại 1 nông trường cải tạo, đúng ra làng Norenskaya, quả đúng là quãng đời đẹp nhất của cuộc đời của ông. [Ui chao, quả đúng như thế thật. Lần đầu Gấu đọc cuốn Chuyện trò với Brodsky của Volkov, chương viết về thời gian lưu đầy nội xứ của Brodsky, GCC cứ nghĩ đến những ngày cải tạo của Gấu, tại nông trường Phạm Văn Cội Củ Chi. Tuyệt vời]. Norenskaya cách Leningrad 350 dặm, và Brodsky có thể gặp những người tới thăm ông. Mẹ của ông, hai ông bạn Rein và Naiman đến thăm; người yêu Basmanova tới, và, ngay cả tình địch và bạn, là Bobyshev, cũng tới! (Ông bạn này đến thăm với hy vọng gặp Basmanova). Brodsky mướn 1 cái lều nhỏ ở trong làng, và tự biên tự diễn, bằng phương tiện của chính ông, biến cái lều thành 1 nhà máy điện, và 1 giếng nước, của riêng ông, khi trong làng không có. “Trong bốn thế hệ thì đây đúng là 1 sự sang trọng, luxury, không thể nghĩ, không thể tin được”, một vị khách thăm đã trầm trồ. Brosdky thì tất nhiên rất ư hãnh diện “khoe hàng”, mỗi lần có khách thăm viếng. Ông có 1 cái máy đánh chữ, và đọc, rất nhiều, Auden. Nói chung thì là, không phải Gulag. Vụ án của ông, được 1 ký giả can đảm, Frida Vigrodova ghi lại, và liền lập tức trở thành hàng chui, samizdat, và được gửi ra nước ngoài, và được dịch ra nhiều ngôn ngữ [ở Mẽo, xuất hiện trên tờ The New Leader.] Một chiến dịch hợp xướng, do Akhmatova và Jean-Paul Sartre chủ xị, cuối cùng đưa đến sự trả lại tự do cho ông. Vào thời gian trở lại Leningrad, cuối năm 1965, Brodsky đã là 1 nhân vật nổi tiếng toàn thế giới. Như vậy vẫn chưa đã: Ông phát triển sâu đậm thơ, "như là nhà thơ". Ông bạn nhà thơ, chôm bạn tình của ông, thì sau đó chìm vào quên lãng. Vào năm 1967, Basmanova sinh cho Brodsky một đấng con trai, và sau đó, hai người, anh đi đường anh, tôi đường tôi. Akmatova mất một năm trước đó, để lại “ban đồng ca thần kỳ”, đã rã đám, tự nó lo cho nó. Bobyshev đổi thành những “đứa trẻ mồ côi của Akhmatova”. Brodsky tiếp tục làm thơ, đi lòng vòng Liên Xô. Khi đám hàn lâm Tây phương tới Leningrad, họ tới thăm ông. Thơ của ông bước vào giai đoạn trưởng thành, đúng thứ thơ của 1 bậc thầy, a total mastery. Bao nhiêu con sóng đã qua đi kể từ đó. Và Brodsky vẫn tiếp tực mơ tả [describe] và nhớ hoài tình của mình dành cho Basmanova. Dịch “phóng bút”, và, “ăn theo”: Cứ mỗi lần tuyết rơi, là anh lại nhớ em, Chẳng có chỗ cho cả hai, Brodsky và chủ nghĩa CS, trong cái xứ sở thật rộng lớn đó. Bè lũ VC Nga bực bội với tất cả những gì Brodsky làm, [cả đến chuyện đi ị, như nhà thơ NCT đã từng bực, đúng vào ngày sinh nhật Bác]. Andrei Sergeev, bạn của Brodsky, sau đó viết: Nhà chức trách không thể làm bất cứ điều chi ngoài chuyện bực, với tất cả những gì Brodsky làm, không làm, đi tản bộ loanh quanh, đứng, ngồi ở bàn, nằm xuống giường, và ngủ. Brodsky vẫn cố tìm đủ cách xb thơ của ông, vô ích. Tới mức, hai ông cớm KGB gật đầu, chúng tao sẽ in thơ của mày, trên loại giấy đặc biệt, bản quí, dành cho "bạn quí" của mày, nếu mày đi một đường báo cáo về những ông giáo sư, bạn của mi, chỉ là báo cáo xuông, những chuyện làm xàm ba láp thôi. Cuốn này, nghe nói, xb không có sự đồng ý của Brodsky, và có nhiều chi tiết, sự kiện không được chính xác. Tuy nhiên, đọc, thú vô cùng. Cái đoạn KGB bắt Brodsky trình diện, năn nỉ ông nạp đơn xin visa xuất ngoại, kiếm bà con dởm cho ông có lý do để đoàn tụ, thật… tếu. Trong một tiểu sử trung thực, thận trọng, quyền uy, Joseph Brodsky: Một đời văn, “Joseph Brodsky: A Literary Life” (Yale; $35; Jane Ann Miller dịch từ tiếng Nga), tác giả, Lev Loseff, bạn cũ của Brodsky đã nhấn mạnh tới cái sự bỏ học “đi hoang” của nhà thơ, với lập luận là, chính cái sự bỏ học này đã khiến nhà thơ không lâm vào tình trạng tẩu hoả nhập ma, khi bị nhồi nhét ba cái thứ, thí dụ, làm toán thì hôm nay làm thịt được mấy tên Mỹ Ngụy, làm thơ thì đường ra trận mùa này đẹp lắm, nói tóm lại, nhờ bỏ học đi làm, Brodsky đã thoát không bị tiêu ma, ruined, bởi sự “bội thực học”. Loseff mô tả lần đầu anh nghe Brodsky đọc thơ. Ðó là vào năm 1961. Trước đó ít lâu, một người nào đó đưa cho anh một xấp thơ của Brodsky, nhưng đánh máy thật khó đọc [bản thảo thơ dưới hầm, thơ chui thường được đánh máy hai ba tờ cùng 1 lượt], và Loseff không khoái những dòng thơ lộn xộn như thế. Tôi tìm cách chuồn, anh nhớ lại. Nhưng lần đó, cả đám chọn ngay căn phòng của vợ chồng ở để mà đọc thơ, thế là thua. Anh bắt dầu đọc bài ballad dài của anh, “Hills,” và Loseff sững sờ: “Tôi nhận ra chúng là những bài thơ mà tôi mơ tưởng mình sẽ viết ra được, ngay cả chưa từng bao giờ biết đến chúng…. Như thể 1 cánh cửa được mở bung ra một không gian mở rộng, một không gian chúng tôi chưa từng biết, hay nghe nói đến. Chúng tôi chẳng hề có 1 ý nghĩ, hay tư tưởng, về thơ Nga, ngôn ngữ Nga, ý thức Nga lại có thể chứa đụng những không gian như thế.” [Ui chao, lại nghĩ đến cái thời kỳ huy hoàng tương tự của cả Miền Nam ngay sau 30 Tháng Tư 1975. GCC khi đó ở trong tù VC, nghe “Con Kinh Ta Ðào” mà nước mắt dàn dụa vì hạnh phúc, “thúi” đến như thế, ”sướng” đến như thế!] Ðiều quan trọng là thơ của Brodsky thì đương thời và địa phương [contemporary and local]. Và cũng còn quan trọng, là, như món nợ đối với chủ nghĩa hiện đại Anh - Mỹ, chúng [những bài thơ của Brodsky] nối kết một nhóm nhỏ của những nhà thơ Leningrad với thế giới lớn lao. Trong giới trí thức, sau đó, nhiều người tin rằng, do niềm tin [a point of faith], nếu không muốn nói, niềm tự hào, nhà nước Liên Xô phát giát ra thiên tài Brodsky, “sớm” hơn tất cả, khi bắt ông. Trong một bài viết về Brodsky, ký giả Mẽo của tờ The New Yorker, David Remnick [Gấu biết đến Brodsky là qua bài viết này, vừa đọc xong là đi 1 đường giới thiệu liền trên tờ Văn Học của NMG] viết, ngay cả bây giờ, một vài sử gia vẫn còn tự hỏi tại sao chính quyền Cộng-sản bắt đầu cuộc thanh trừng bằng cách bắt giữ một nhà thơ 23 tuổi chưa được nhiều người biết tới. Nhưng đó chỉ là một bí mật đối với người nào còn nghi ngờ bản năng của thú dữ khi nhận ra đâu là nguy cơ lớn lao nhất đối với chế độ. Và bắt lầm còn hơn bỏ sót. Vụ án, ra toà của Brodsky gồm hai đợt, cách nhau vài tuần lễ, vào Tháng Hai và Tháng Ba 1964, và giữa hai lần, Brodsky nằm nhà thương tâm thần, ở đó, ông được giới y sĩ nhà nước chứng nhận, chẳng bịnh tật gì hết, dư sức ra tòa, nhận án. Vụ án là trò hề, án tòa thì đã có sẵn, trước khi có vụ án, và có cái tên là “Vụ án tên ăn hại, ăn bám Brodsky”, như cái biển gắn bên ngoài phòng luận tội. Nhân dân buộc tội số 1: Ông khi đó chưa được 24 tuổi đầu, hà, hà! Rein, bạn của Brodsky nhớ lại, đợt ra tòa lần thứ nhì rơi đúng vào dịp lễ Maslenitsa, hay Butter Week, lễ truyền thống đợp bánh pancake, và hậu quả là, vào đúng ngày tòa xử, Rein cùng đám bạn rủ nhau tới khách sạn làm 1 chầu, và tới 4 giờ cả bọn kéo tới tòa án. Chẳng đấng bạn nào ngửi ra cái mùi trầm trọng của sự kiện. Cái đoạn David Remnick, ký giả Mẽo của tờ Người Nữu Ước viết về Brodsky ra tòa mới thật là tuyệt vời, và nhìn ra được vai trò của ông, sinh ra là để đóng cái vai của mình, dù đếch có muốn. Có nhiều nhà thơ có tài, có thể ở vào chỗ anh ta khi đó, Efim Etkind viết. Nhưng số phận đã chọn đúng anh ta, và ngay lập tức anh hiểu trách nhiệm về địa vị của anh - không còn là một con người riêng tư, nhưng trở thành một biểu tượng, như Akhmatova đã trở thành một biểu tượng quốc gia của người thi sĩ Nga, khi bà bị số phận lọc ra giữa hàng trăm nhà thơ, năm 1946. Thật quá nặng cho Brodsky. Ông có một bộ não tệ, một trái tim tệ. Nhưng ông đã đóng vai ông tại tòa án một cách tuyệt vời. Thế đấy. Theo nghĩa thế đấy, cái vai tuyệt vời mà Ông Giời dành cho thi sĩ mê gái HC, là, khi bị Tố Hữu bắt viết tự kiểm, thì bèn phán, ông đếch viết, được không. Việc nào ra việc đó! Hà, hà! Không ngừng cựa quậy, làm thợ được 6 tháng, nghỉ. Trong vòng 7 năm tiếp theo cho tới khi bị nhà nước tóm, ông làm việc ở 1 hải đăng [light-house], một phòng thí nghiệm crystallography, 1 nhà xác. Ông cũng đi lêu bêu, hút thuốc, và đọc sách. Du lịch lòng vòng Liên Xô, tham dự những cuộc thám hiểm địa chất, đào bới đất nước tìm dầu hôi, khoáng sản. Ðêm đêm, giữa những nhà địa chất ngồi quanh một đống lửa, họ hát hỏng, đọc thơ, gẩy ghi ta. Ðọc 1 tập thơ về đề tài địa chất, Brodsky tự nhủ thầm, nếu mình làm, chắc chắn sẽ khá hơn. Một trong những bài thơ đầu đời của ông, “Pilgrims” [những kẻ hành hương], chẳng mấy chốc trở thành “top hit” của lửa trại. Ðường phố Leningrad cà mèng, nhưng Brodsky và mấy đấng bạn thân - Bobyshev, Anatoly Naiman, và Evgeny Rein, “dàn đồng ca thần kỳ” – tóm lấy chúng mỗi khi dịp. Bobyshev, trong hồi ký của mình nhớ lại, Brodsky kéo anh tới mép bờ của thành phố để anh ta có thể đọc thơ cho vài nhóm sinh viên. Bobyshev bỏ cuộc vui sớm nhất. [Ui chao, lại nghĩ đến cái thời kỳ huy hoàng tương tự của cả Miền Nam ngay sau 30 Tháng Tư 1975. GCC khi đó ở trong tù VC, nghe “Con Kinh Ta Ðào” mà nước mắt dàn dụa vì hạnh phúc, “thúi” đến như thế, ”sướng” đến như thế!] Brodsky sinh Tháng Năm 1940, một năm trước khi Nazi xâm lăng Nga. Bà mẹ làm kế toán, cha, nhiếp ảnh viên cho Viện Bảo Tàng Hải Quân ở Leningrad khi Brodsky còn nhỏ, và là đứa con độc nhất của hai vợ chồng thực yêu thương nhau, và được đứa con thực thương yêu. Brodsky cũng nghĩ như thế. “Sau đó, tôi lấy làm tiếc cho cái sự bỏ học sớm, nhất là khi thấy mấy đấng bạn quí leo cao trên những bậc thang xã hội, lặn sâu vào trong chính quyền,” ông viết, “Nhưng, tôi hiểu ra một điều mà họ không hiểu được. Sự thực, tôi cũng đi tới, đi lên, nhưng ngược chiều với họ, và có vẻ như, vừa đi ngược chiều, tôi vừa đi xa hơn họ”. Cái chiều ngược này có thể gọi bằng nhiều tên: dưới hầm, chui, samizdat, hay tự do, hay Tây Phương. Your voice, your body, your name Tiếng nói của em, thân thể của em, tên của em Brodsky sinh tháng Năm 1940, trước khi Nazi xâm lăng Nga. Bà mẹ làm kế toán viên, cha nhiếp ảnh viên làm cho Bảo Tàng Viện Hải Quân Leningrad khi Brodsky còn nhỏ. Bố mẹ rất thương yêu nhau và được ông con trai độc nhất, Iosif Brodsky, rất thương. Note: The Gift: Món quà tặng, Thiên bẩm, Thiên phú... Vào mùa đông năm 1963, ở Leningrad, ở cái xứ còn có tên là Liên Bang Xô Viết, nhà thơ trẻ Dmitry Bobyshev chôm cô bạn gái của bạn mình, cũng nhà thơ trẻ, Joseph Brodsky. In his autobiographical journeying Brodsky never reached the 1960s, the time of his notorious trial on charges of social parasitism and his sentencing to corrective labor in the Russian far north. This silence was, in all likelihood, deliberate: a refusal to exhibit his wounds was always one of his more admirable traits ("At all costs try to avoid granting yourself the status of the victim," he advises an audience of students; On Grief, p. 144). Coetzee: Joseph Brodsky Như Coetzee viết, một trong những nét đẹp nhất của Brodsky “mình ên”, là không bao giờ khoe khoang những vết thương của mình. Ông gần như chẳng bao giờ nhắc tới thời gian đi tù. Nhưng đây là quãng đời đẹp nhất của chàng, qua bài viết cho thấy. Your voice, your body, your name Tiếng nói của em, thân thể của em, tên của em Thua xa Gấu. Gấu chỉ 1 đời. In his autobiographical journeying Brodsky never reached the 1960s, the time of his notorious trial on charges of social parasitism and his sentencing to corrective labor in the Russian far north. This silence was, in all likelihood, deliberate: a refusal to exhibit his wounds was always one of his more admirable traits ("At all costs try to avoid granting yourself the status of the victim," he advises an audience of students; On Grief, p. 144). Coetzee: Joseph Brodsky Vào mùa đông năm 1963, ở Leningrad, ở cái xứ còn có tên là Liên Bang Xô Viết, nhà thơ trẻ Dmitry Bobyshev chôm cô bạn gái của bạn mình, cũng nhà thơ trẻ, Joseph Brodsky. Họ thường xuất hiện theo vần abc, ở những buổi đọc thơ công cộng lòng vòng trong thành phố. Bobyshev khi đó, hăm bảy, mới tan tác với bà vợ; Brodsky hăm ba, lúc có việc làm, lúc không. Cùng với hai nhà thơ trẻ khác, cũng tràn trề hứa hẹn, họ tạo thành ban “đồng ca huyền ảo”, như cái nick bè bạn và bà chị, nhà thơ đỡ đầu Akhmatova ban cho. Nữ thần thi ca Nga, hiện đang còn sống vào lúc đó, tin tưởng, họ đại diện cho cái sự trẻ măng, và làm mới truyền thống thi ca Nga, sau những năm tháng đen tối dưới thời Stalin. Khi được hỏi, ai trong số những nhà thơ đó được ái mộ nhất, bà nêu tên đúng hai mạng: Bobyshev và Brodsky. Joseph Brodsky and the fortunes of misfortune. by Keith Gessen May 23, 2011 . Note: Bài này, cái tít ở trang bìa, báo giấy, thú hơn nhiều: Bạn và người yêu của Joseph Brodsky. Đếch ra cái chó gì cả, nhỉ. Hai đấng thi sĩ trẻ lại rất thân.

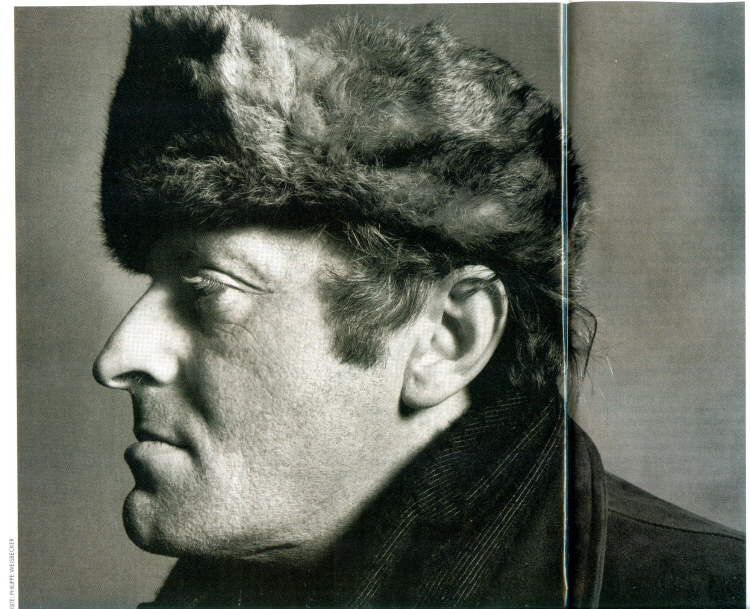

Brodsky experienced all the struggles of his generation on his own hide, as the Russians say. His exile was no exception. Photographed, in 1980, by Irving Penn.

The young Soviets felt the sixties even more deeply than their American and French counterparts, for, while the Depression and the Occupation were bad, Stalinism was worse. After Stalin died, the Soviet Union began inching toward the world again. The ban on jazz was lifted. Ernest Hemingway was published; the Pushkin Museum in Moscow hosted an exhibit of the works of Picasso. In 1959, Moscow gave space to an exhibition of American consumer goods, and my father, also a member of this generation, tasted Pepsi for the first time. The libido had been liberated, but where was it supposed to go? People lived with their parents. Their parents, in turn, lived with other parents, in what were known as communal apartments. “We never had a room of our own to lure our girls into, nor did our girls have rooms,” Brodsky later wrote from his American exile. He had half a room, separated from his parents’ room by bookshelves and some curtains. “Our love affairs were mostly walking and talking affairs; it would make an astronomical sum if we were charged for mileage.” The woman with whom Brodsky had been walking and talking for two years, the woman who broke up the magical chorus, was Marina Basmanova, a young painter. Contemporaries describe her as enchantingly silent and beautiful. Brodsky dedicated some of the Russian language’s most powerful love poetry to her. “I was only that which / you touched with your palm,” he wrote, “over which, in the deaf, raven-black / night, you bent your head. . . . / I was practically blind. / You, appearing, then hiding, / taught me to see.” Almost unanimously, people in their circle condemned Bobyshev. Not because of the affair—who didn’t have affairs?—but because, as soon as Bobyshev began to pursue Basmanova, Brodsky began to be pursued by the authorities. In November, 1963, an article appeared in the local paper insulting Brodsky, his trousers, his red hair, his literary pretensions, and his poems, although of the seven quotations offered as examples of Brodsky’s poetry, three were by Bobyshev. Everyone recognized this sort of article as a prelude to an arrest, and Brodsky’s friends insisted that he go to Moscow to wait things out. They further insisted that he check himself into a mental hospital, in case a determination of some form of psychosis could help him plead his case. Brodsky met the New Year in the hospital, then begged to be released. Upon getting out, he learned that Bobyshev and Basmanova had been together on New Year’s at a friend’s dacha. Brodsky borrowed twelve rubles for train fare and raced up to Leningrad. He confronted Bobyshev. He confronted Basmanova. Before he could get much further, he was thrown in jail. The subsequent trial launched the Soviet human-rights movement, turned Brodsky into a world-famous figure, and resulted in his eventual exile from the U.S.S.R. Brodsky was born in May, 1940, a year before the German invasion. His mother worked as an accountant; his father was a photographer and worked for the Navy Museum in Leningrad when Brodsky was young. They were doting parents and much beloved by Iosif Brodsky, who was their only child. Leningrad suffered terribly during the war—it was blockaded for more than two years by the Germans, deprived of food and heat. An aunt starved to death. In the immediate postwar years, even as Stalin mobilized the country for the Cold War, the damage was plain to see. “We entered schools, and whatever elevated rubbish we were taught there, the suffering and poverty were visible all around,” Brodsky wrote. “You cannot cover a ruin with a page of Pravda.” He was an uninspired student, held back in the seventh grade. When his parents started having financial trouble—his father lost his Navy job during Stalin’s late-life campaign against the Jews—Iosif, fifteen, dropped out and went to work in a factory. In a loyal, scrupulous, and authoritative biography, “Joseph Brodsky: A Literary Life” (Yale; $35; translated from the Russian by Jane Ann Miller), Brodsky’s old friend Lev Loseff puts a great deal of emphasis on his subject’s decision to drop out of school, arguing that it prevented Brodsky from being ruined by over schooling. Brodsky thought so, too. “Afterward I often regretted that move, especially when I saw my former classmates getting on so well inside the system,” he wrote. “And yet I knew something that they didn’t. In fact, I was getting on too, but in the opposite direction, going somewhat further.” The direction he was going could be called, variously, underground, or samizdat, or freedom, or the West. He was restless. He left the factory job after six months. Over the next seven years, until his arrest, he worked at a lighthouse, a crystallography lab, and a morgue; he also hung about, smoking cigarettes and reading books. He travelled around the Soviet Union, taking part in “geological” expeditions, helping the rapidly industrializing Soviet government comb the vast country for mineral wealth and oil. At night, the geologists would gather around the campfire and play songs on their guitars—often poetry set to music—and read their own poems. Upon reading a book of poems on the “geological” theme, in 1958, Brodsky decided that he could do better himself. One of his earliest poems, “Pilgrims,” was soon a campfire hit. The whole country was going crazy for poetry; it had become central to the atmosphere of Khrushchev’s Thaw. In 1959, as part of a return of sorts to the Bolshevik past, a statue of Vladimir Mayakovsky was unveiled in central Moscow, and soon young people began to gather around it to read their own poetry. In the early sixties, a group of poets started a series of well-attended readings at the Polytechnical Museum in Moscow, catercorner from the headquarters of the K.G.B. There is a film of one of these evenings, and, though it’s just a poetry reading (rather than a Beatles concert, say), and though the poems of these semi-official poets weren’t especially good, the atmosphere is electric. A crowd had gathered and before it stood a young man talking about his feelings: this was new. The venues in Leningrad were more humble, but Brodsky and his closest poet-friends—Bobyshev, Anatoly Naiman, and Evgeny Rein, the “magical chorus”—took advantage of them whenever they could. Bobyshev in his memoir recalls Brodsky dragging him to the edge of town so Brodsky could read some poems to a group of students. Bobyshev left early. As for the poetry itself, Loseff argues convincingly that the early work—before Brodsky’s arrest—is uneven, sometimes derivative. But from the start Brodsky was one of those poets who can write confessionally and make it sound as if they were describing an entire social phenomenon. The poems are romantic, sarcastic, and effortlessly contemporary. There is an Eliot-like elongation of the poetic line, and a sense of surprise when the rhyme and meter are maintained; there is also the clear influence of the English Metaphysical poets, who laced their love poetry with philosophical speculations—in Brodsky’s case, always relating to time and space. Searching for English-language equivalents, Robert Hass wrote that Brodsky sounded “like Robert Lowell when Lowell is sounding like Byron.” As a cultural figure in Russia, though, Brodsky was more akin to Allen Ginsberg (with whom he later went shopping for used clothes in New York—“Allen bought a tuxedo jacket for five dollars!” he told Loseff, who wondered why a beatnik needed formal wear). For Ginsberg and his friends, freedom lay in breaking the bounds of traditional prosody; for Brodsky and his friends, freedom came from reëstablishing a tradition that Stalin had tried to annihilate. Brodsky was able to find surprising ways of doing this, seemingly with no effort, and always remaining cool and nonchalant. His early poems describe the narrator walking home from the train station; the narrator touring his old Leningrad haunts; the narrator watching a married couple argue, wondering whether he himself will always be alone. That last one, incidentally, is called “Dear D. B.,” that is to say, Dmitry Bobyshev, who was in an unhappy marriage at the time. Loseff describes the first time he heard Brodsky read. It was 1961. Some time before, a friend had given him a sheaf of Brodsky’s poems, but the type was faint (samizdat manuscripts were often typed three or four sheets at a time), and Loseff didn’t like the look of the lines, which, especially in Brodsky’s early poetry, stretched on and on. “I managed to get out of reading them somehow,” Loseff recalls. But now a group of friends had gathered in the communal apartment where Loseff and his wife lived, and there was no getting away from Brodsky. He started reading his long ballad “Hills,” and Loseff was amazed: “I realized that here at last were the poems I had always dreamed of, without even knowing it. . . . It was as if a door had opened into a wide-open space that we hadn’t known about or heard of. We simply had no idea that Russian poetry, that the Russian language, that Russian consciousness, could contain these spaces.” Many people felt this way when they first encountered Brodsky’s poems. One friend who got hauled in for a talk with the K.G.B. around this time recalls telling his interrogator that, of all the people he knew, Brodsky was the likeliest to win the Nobel Prize. It was a period of tremendous generational energy and hope; someone had to embody it. It was important that Brodsky’s poems were contemporary and local. It was also important that, in their debt to Anglo-American modernism, they connected the small group of Leningrad poets and readers to the great world. And most important of all was that, in their creative fealty to an old-fashioned formal tradition, they connected this generation to the great poets of the Russian past; Nadezhda Mandelstam, the poet’s widow, declared Brodsky a second Mandelstam. Then, in October, 1962, Khrushchev was confronted by President Kennedy over a shipment of missiles sent by the Soviets to Cuba. After a tense standoff, the Soviets withdrew in humiliation, and Khrushchev lashed out at home. Just a few weeks after the Cuban missile crisis, he lambasted a group of young artists at an exhibit in Moscow, calling them “faggots.” The Thaw was finished. A year later, Brodsky was charged with “freeloading” on the back of the great Soviet people. Among the intelligentsia, it later be came a point of faith, if not exactly of pride, that the Soviet regime had intuited Brodsky’s greatness earlier than just about anyone. Loseff deflates this notion; in fact, he explains, the initiative for the arrest came from the head of a community-watch group; he had heard of Brodsky’s local fame and Brodsky happened to live within his jurisdiction in Leningrad. That was all. The Soviet regime stumbled onto one of the great prodigies in the history of the Russian language pretty much by accident. Brodsky’s trial took place in two sessions, several weeks apart, in February and March of 1964; in between, Brodsky was confined to a mental hospital, where it was determined that he was psychologically fit to work. The trial was a farce, its outcome predetermined. “Trial of the freeloader Brodsky,” a sign outside the courtroom read, a little prejudicially. Inside, neither the judge nor the people testifying against Brodsky had any interest in his poetry. Brodsky, who remained unpublished, made what money he could doing translations, sometimes working from literal translations when he didn’t know the source language; his accusers wanted to know, among other things, how this was possible, and whether Brodsky wasn’t exploiting his collaborators on such projects. Much of the case turned on whether writing was a real job if it brought little or no income:

Brodsky at the time was not yet twenty-four. His friend Rein recalls how the second session of the trial fell on Maslenitsa, or Butter Week, the traditional pancake-eating holiday in advance of Lent. Consequently, on the day of the trial, Rein and some other friends went to the restaurant at the Hotel European to eat pancakes. Then, at four o’clock, they went to the courthouse. Not everyone, in other words, had a sense of the gravity of the occasion. Brodsky did. Throughout the short trial, he appears to have been serious, quiet, respectful, and firm in his conviction about what he was put on earth to do:

In the end, the judge sentenced the so-called poet to five years of exile and labor up north, to straighten him out. On the subject of Brodsky’s exile, Loseff is once again forced to disappoint readers who have grown accustomed to thinking of the poet as someone who spent time in the Gulag. His confinement to a mental hospital in between sessions of the trial was miserable. His eighteen months in the village of Norenskaya were among the best times of his life. Norenskaya was three hundred and fifty miles from Leningrad, and Brodsky could receive visitors. His mother visited him; his friends Rein and Naiman visited; his lover Basmanova visited. Even Bobyshev came to visit! (He was looking for Basmanova.) Brodsky rented a little cottage in the village and, while it didn’t have central heating or plumbing, it was, as one visitor marvelled, his very own. “For our generation this was an unthinkable luxury,” the visitor recalled. “Iosif proudly showed off his domain.” Brodsky had a typewriter and was reading a lot of W. H. Auden. On the whole, this was more Yaddo than Gulag. But there is nothing to be done about a legend once it’s created. Akhmatova’s famous dark joke at the time of his arrest—“What a biography they’re writing for our redhead”—told only half the story. After his arrest, Brodsky met the occasion; he built his own biography. The transcript of the trial, made by a brave journalist named Frida Vigrodova, quickly appeared in samizdat and was sent abroad, where it was published in many languages (in the United States it appeared in The New Leader). A concerted campaign led by Akhmatova and joined by Jean-Paul Sartre resulted in Brodsky’s early release. By the time he returned to Leningrad, in late 1965, Brodsky was world famous, and had developed profoundly as a poet. Bobyshev no longer stood a chance. In 1967, Basmanova gave birth to Brodsky’s son, and then broke things off with him again. Akhmatova had died the year before, leaving the already splintering magical chorus to fend for themselves. (Bobyshev rechristened them “Akhmatova’s orphans.”) Brodsky kept writing poetry and travelling around the Soviet Union. When Western academics came to Leningrad, they visited him. His poetry entered a phase of maturity and total mastery. Brodsky continued to describe his life. One poem recalls a seaside meeting between two friends, and then goes on:

And he also continued to describe and memorialize his love for Basmanova. From “Six Years Later,” in Richard Wilbur’s translation:

There was not room enough in the U.S.S.R. for both Brodsky and the Communists. “The authorities couldn’t help but be offended by everything he did,” his friend Andrei Sergeev later wrote. “By his working, by his not working, by his walking around, standing, sitting at a table, or lying down and sleeping.” Brodsky kept trying to get his poems published, to no avail. At one point, two K.G.B. agents promised to publish a book of his poems on high-quality Finnish paper if he would only write the occasional report about his foreign-professor friends. Nor was there a place for Brodsky in the growing dissident human-rights movement that his own trial had helped catalyze. His relation to the dissidents somewhat resembled Bob Dylan’s to the American student movements of that era: sympathetic but aloof. In the early nineteen-seventies, the geopolitical wheel turned again, and took Brodsky with it. Brezhnev’s desire to clear house dovetailed nicely with pressure from the West to release Soviet Jews, and in the spring of 1972 Brodsky was given three weeks to pack his bags and board a plane to Vienna. Unlike Norenskaya, this would be true exile, and it lasted the rest of his life. In Vienna, Brodsky was met by Carl Proffer, a Russian-literature professor at the University of Michigan, who was just starting Ardis, a small publishing house. Proffer happened to know that Brodsky’s hero, Auden, was vacationing nearby, and they decided to pay him a visit. Despite receiving no advance warning, Auden welcomed the exiled poet, and a few months later Brodsky wrote home to Loseff, using newfound English words wherever possible:

And thus Brodsky’s charmed life in the West began. Brodsky makes a cameo appearance in the novelist Sigrid Nunez’s new memoir about Susan Sontag, “Sempre Susan.” It is 1976 and Brodsky has recently started dating Sontag. He is romantic, brooding, mostly bald. “None of it matters,” he announces one day. “Not suffering. Not happiness or unhappiness. Not illness. Not prison. Nothing.” (“Now, that’s European,” Nunez writes, a dig at Sontag.) Another time, he takes everyone out for Chinese, his favorite New York meal. Sitting around the table with Sontag, her son, and the young Nunez, Brodsky is the bohemian paterfamilias. Nunez describes him purring to this small, unlikely clan, “Aren’t we happy?” This is the image one has of Brodsky in America: a runaway success. Only from the Russian side can one see how difficult it was, and also just how much it meant. For members of that Soviet generation, America was everything. They listened to its music, read its novels, translated its poetry. They caught bits and pieces of America wherever they could (including on trips to Poland). America “was like a homeland in reserve for us,” Sergeev (who translated, among others, Robert Frost) later wrote. When, in the nineteen-seventies, the opportunity presented itself, many went. It was only upon arriving here that they discovered what they’d lost. Brodsky was one of the first. In later years, enough people came over so that Russian communities formed in Boston, New York, Pittsburgh, but in 1972 America was as lonely as the village of Norenskaya. There weren’t any Russians to talk to, Brodsky complained in letters home, and, as for the local Russian-literature professors, “They had come to resemble their subjects like masters their dogs.” So that was out. Brodsky’s poems during his first years in the States are filled with the most naked loneliness. “An autumn evening in a humble little town / proud of its appearance on the map,” one begins, and concludes with an image of a person whose reflection in the mirror disappears, bit by bit, like that of a street lamp in a drying puddle. The enterprising Proffer had persuaded the University of Michigan to make Brodsky a poet in residence; Brodsky wrote a poem about a college teacher. “In the country of dentists,” it begins, “whose daughters order clothes / from London catalogues, . . . / I, whose mouth houses ruins / more total than the Parthenon’s, / a spy, an interloper, / the fifth column of a rotten civilization,” teach literature. The narrator comes home at night, falls into bed with his clothes still on, and cries himself to sleep. That year, Brodsky wrote a poem indicating that, in being forced to leave Russia, he lost a son. “My dear Telemachus,” it begins, “The Trojan war is over,” and continues (in George L. Kline’s rendering):

Eventually, Brodsky escaped the country of dentists for a small garden apartment on Morton Street, in the West Village, which he rented from a professor at N.Y.U., and took a teaching post at Mount Holyoke, in western Massachusetts. He found his level, socially, and his complaining letters home took a curious turn. “Last week, I had the first conversation in three years about Dante,” one went, “and it was with Robert Lowell.” In 1976, Brodsky was joined in the U.S. by his old friend Loseff, who became his best reader and a close observer of his American life. In Leningrad, the bookish Loseff had worked as the sports editor of a magazine for kids. In the U.S., he initially settled, like Brodsky, in Ann Arbor, working for Proffer’s Ardis, before moving to New England, in Loseff’s case Dartmouth, where he taught Russian literature until his death, in 2009. As a biographer, Loseff is honorable, supremely intelligent, and almost supernaturally well informed. He shows how the important experiences in Brodsky’s life appear in his poems—in fact, the book was written as a side project while Loseff was preparing a two-volume annotated edition of Brodsky’s poetry, which will appear in Russia later this summer. He never strays more than is absolutely necessary into Brodsky’s personal life. “The book is in the style of ‘everything you always wanted to know about Brodsky but were afraid to ask,’ if the thing you were afraid to ask about was his metaphysics rather than his wife,” a reviewer wrote of the book when it came out in Russia. But Loseff has also left a book of autobiographical essays, “Meander,” published posthumously, in Russian, in 2010, under the editorship of the poet Sergei Gandlevsky. No less loyal and affectionate toward Brodsky, the short essays in this book are much more personal and personable, and Brodsky appears in them in a slightly different light. Loseff comes to visit him in New York to eat Chinese food and read poetry. Also to receive clothes: according to Loseff, Brodsky was always buying huge amounts of clothing at the secondhand clothing shops of Manhattan, then giving them to Loseff, who was about the same size. One essay opens with Loseff house-sitting for Brodsky on Morton Street; suddenly the phone rings in the middle of the night, and a female voice on the other end of the line, speaking English and mistaking Loseff for Brodsky, demands to know what he is doing. “Stupidly I said, ‘Sleeping,’ ” Loseff writes. “What then began to happen on the other end of the line caused me some embarrassment, so I replaced the receiver, with unnecessary tact.” The essay goes on to defend Brodsky from accusations of womanizing. In these essays, Loseff is able to say some of the things that Brodsky could not. Even after moving to New York, Brodsky continued to play it cool. To any interviewer who asked, he would say that America is merely “a continuation of space.” Or in “Lullaby of Cape Cod” (in Anthony Hecht’s translation):

Loseff could never be so cool. He was taken with America. “Even now, having lived here thirty years,” he writes, “I sometimes feel a strange elation: is this really me, seeing this foreign land with my own eyes, taking in these other smells, speaking to the local people in their language?” Brodsky’s own English improved rapidly. Almost immediately upon his arrival in the U.S., he began publishing essays, translated from the Russian by his friends, in the American intellectual press. In 1977, he bought a secondhand typewriter in Manhattan and soon was writing the essays directly in a supple, playful, ironic English, through which you could sometimes hear the poetic voice of his Russian. In these essays, many of which appeared in The New York Review of Books, Brodsky wrote with great sympathy of the poets he most admired: Marina Tsvetaeva, Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, and, on the other shore, Robert Frost and, especially, Auden. In this way he was able to repay his debts. He was also able, in several autobiographical essays, to recast his painful experiences in a new form. As he wrote in one essay about his parents, who died in the mid-eighties, unable to see their son after his expulsion from the U.S.S.R.:

His English was able to grant his parents a measure of freedom. But there was one thing it could not do: transform his Russian poetry into English poetry. Inevitably, Brodsky tried, and he wasn’t shy about it. Almost as soon as his English was up to snuff he began to “collaborate” with his translators; eventually he supplanted them. The results were not so much bad as badly uneven. For every successful stanza, there were three or four gaffes—grammatical, or idiomatic, or just generally tin-eared. Worst of all, to readers accustomed to postwar Anglo-American poetry, Brodsky’s translations rhymed, no matter what obstacles stood in their way. From the very first, it had fallen to Brodsky to experience all the struggles of his generation on his own hide, as the Russians say. His immigration was no exception. He was spared the loss of social status that tormented other immigrants (indeed, the memoirs of later immigrants who had known him in Leningrad are filled with tales of how Brodsky didn’t introduce them to another luminary, or pretended not to see them while doing a reading somewhere). Although his health was poor (he had his first heart attack in 1976), he was spared the material concerns many immigrants had. But he was not spared the dislocation, the misunderstanding. He failed to see that the social changes that made his poetry resonant in Russian had obviated just this kind of poetry in the States. Writing about his generation of idealistic Russians, he put it best: “Hopelessly cut off from the rest of the world, they thought that at least that world was like themselves; now they know that it is like the others, only better dressed.” In his last decade, Brodsky achieved an unprecedented level of success. He was awarded the 1987 Nobel Prize for Literature. Afterward, he spent a lot of time in Italy, got married to a young student of Russian and Italian descent, became the Poet Laureate of the United States, moved to Brooklyn. In 1993, his wife gave birth to a daughter, whom they named Anna. As often happens, Brodsky was more visible in his last years as an essayist and a propagandist for poetry than as an actual poet. His ideas about the moral importance of poetry—inherited from the poets of the Silver Age, including Mandelstam, who had died for his poetry—eventually hardened into dogma; his Nobel Prize address stressed that “aesthetics is the mother of ethics,” and so on. Poetry was immortal, he argued: “That which is being created today in Russian or English, for example, secures the existence of these languages over the course of the next millennium.” But this wasn’t true, as Brodsky eventually acknowledged in a great and furious late poem, “On Ukrainian Independence,” in which he berated the independence-minded Ukrainians for casting aside the Russian tongue. “So go with God, you swift cossacks, you hetmans, you prison guards,” it says, and concludes:

Alexander Pushkin, that is. Despite itself, the poem is an anguished admission that a Russian state and Russian-speaking subjects are still vital to the project of Russian poetry. Brodsky never returned to Russia. Nor did he see Marina Basmanova again, though their son, Andrei, came to visit New York once, and the two did not get along. A friend recalls Brodsky calling her in Boston to ask if he should buy the young man a VCR, even though, Brodsky complained, he’d dropped out of college and refused to work. In 1989, Brodsky wrote his last poem to “M.B.,” his old muse, describing himself out for a walk and breathing the fresh air and remembering Leningrad. “Don’t get me wrong,” it goes on:

The magical chorus had fallen apart. Even Rein and Naiman eventually quarrelled, with Naiman, in one of his many memoirs, accusing Rein of bringing a can of apricot compote to a dinner party and then eating all of it himself. In late January, 1996, Brodsky died, of his third heart attack, after a life of not taking very good care of himself. “If you can’t have a cigarette with your morning coffee,” he once said, “there’s no point getting up.” Bobyshev eventually emigrated to the States. He settled in Illinois, where he, too, taught literature. After Brodsky’s death, he published his account of his early years, including the Basmanova affair. There is a great scene in which he visits his aunt in Moscow. Akhmatova is in town at the same time and gives him a call while he’s out. When he gets back, his aunt is flabbergasted. “Is it possible that Anna Akhmatova called for you?” she asks. “Yes, of course,” young Bobyshev replies airily. “What did she say?” The book ends with Bobyshev, now in America, calling Brodsky in New York. They haven’t spoken in two decades, but Bobyshev has an important matter relating to Akhmatova to discuss with him, and they briefly put their differences aside. They settle the matter, and then Brodsky asks, “So how do you like America?” It’s not easy, Bobyshev says, but still it’s an interesting place. “What about it is interesting?” Brodsky asks. Bobyshev says it’s all very interesting, the colors, the faces, all of it. “Hmm,” Brodsky says. And they hang up. ♦ Posted by Keith Gessen A few months ago, I published an essay in the magazine about the poet Joseph Brodsky; the essay was partly a review of a new biography of Brodsky by his great friend and fellow émigré Lev Loseff. In Loseff’s book, I learned about a poem Brodsky had written in the early nineteen-nineties lamenting the splitting-off of Ukraine from Russia. Part of the reason I’d never heard of the poem is that it had never been published; Brodsky read it aloud once, at Queens College in New York in 1994, but never again circulated the poem. Loseff describes it as “the lone act in his life of self-censorship.” I’ve since received a note from Brodsky’s literary executor, Ann Kjellberg, mildly rebuking me for not pointing out the complex circumstances of the poem, both political and bibliographic. “A poem known only from private manuscripts and other unauthorized sources should perhaps not be taken as representing an author’s settled views,” she writes. “Dating and historical circumstances might also be borne in mind when considering an archival source. In the summer of 1992, for example, newly independent Ukraine declared administrative control over former Soviet nuclear capability on its territory, including 176 ICBMs. Perhaps somewhat inflaming circumstances, later reconsidered.” This is entirely fair and true. Kjellberg also points out that the poem first received wide circulation, after Brodsky’s death, when it was republished by Ukrainian nationalists and cited as an instance of Brodsky’s extreme pro-Russian views. The imputation to Brodsky of Russian nationalist views is of course paradoxical, and worth considering. Brodsky was Jewish, a fact of which his countrymen occasionally, aggressively reminded him (and still do, as a matter of fact, in the comment threads on Russian Web sites); Russia had imprisoned him and then sent him packing; and the government had refused his parents’ requests to visit their only child. A close and dear friend of Brodsky’s was Tomas Venclova, considered the greatest of Lithuanian poets, and no doubt Brodsky thrilled to see Lithuania stand up to the Soviet behemoth in 1990 and 1991 and fight for its independence (and achieve it). But, like so many of the developments in the post-Soviet space, it was complicated. Brodsky was a strongly anti-Soviet Soviet poet, but a Soviet poet nonetheless. His poems required a complex understanding of Russian. Soviet schools—the ones Brodsky hated so viscerally that he dropped out of them at an early age—taught people Russian. They taught them Russian in Almaty, and Tashkent, and Samarkand; in Tallinn, Riga, Vilnius; in Sevastopol, Lvov, and Kiev. Most of these places had been part of the Russian Empire, which the Soviets inherited; but the Soviets defended it (as the inheritors of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires were unable to do), and they even expanded it. More people were learning Russian when Brodsky was writing his poems than had ever learned Russian before. How, as a Russian poet whose poems would famously resist translation, could one not be happy about that? In the past few years, I’ve travelled to some of the places where Russian language and Russian culture were made part of the fabric of life long before Lenin arrived at Finland Station, and where Russian is now being rolled back, post-1991. Even though there is a strong argument to be made for federation; even though the local élites who are the most fervid proponents of independence do not always have most people’s best interests at heart; and even though there are many places whose quality of life has demonstrably worsened since the fall of the Soviet Union, it’s hard not to root for nations, and cultures, and languages that have long been subordinate to Moscow and Russian. At the same time, for a speaker of Russian and admirer of Russian culture, it is also hard not to be a little sad about it, too. These processes will take time, but in thirty years it’s possible that very few people will speak Russian on the streets of Almaty; the same may be true in fifty or a hundred years in Kiev, birthplace of Mikhail Bulgakov, and Odessa, hometown of Isaac Babel. Well, too bad for the Russians, you say, and I agree. People who can’t speak Russian will be less susceptible to Russian propaganda. But they will also be less susceptible to the poetry of Joseph Brodsky. “On Ukrainian Independence” was, in a serious sense, politically incorrect, and this is why Brodsky never published it. But it expressed a real and legitimate anguish, and it happens to be a great poem. As Brodsky writes toward the end: А что до слезы из глаза—нет на нее указа, ждать до дргого раза. Meaning, roughly: “As for the tears in my eyes/ I’ve received no orders to keep them for another time.” |

Comments

Post a Comment